Peter Scott (police Chief) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Peter Markham Scott (14 September 1909 – 29 August 1989) was a British

Scott was born in London at 174,

Scott was born in London at 174,

Then he served in

Then he served in

Scott stood as a

Scott stood as a  As a member of the

As a member of the

Article illustrated with his paintings

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Scott, Peter 1909 births 1989 deaths English ornithologists British conservationists English activists Cryptozoologists English television presenters Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust English illustrators 20th-century English painters English male painters 20th-century English writers Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) British stamp designers English male sailors (sport) Sailors at the 1936 Summer Olympics – O-Jolle Olympic sailors for Great Britain Olympic bronze medallists for Great Britain 1964 America's Cup sailors Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Knights Bachelor Anglo-Scots Chancellors of the University of Birmingham Rectors of the University of Aberdeen Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge People educated at West Downs School People educated at Oundle School English people of Scottish descent English conservationists British bird artists Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War II Olympic medalists in sailing Camoufleurs 20th-century British zoologists Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Medalists at the 1936 Summer Olympics Scott family (conservationists), Peter Presidents of World Sailing English sports executives and administrators Military personnel from the City of Westminster 20th-century English male artists 20th-century English sportsmen Fellows_of_the_Zoological_Society_of_London

ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

, conservationist, painter, naval officer

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer (NCO), or a warrant officer. However, absent ...

, broadcaster and sportsman. The only child of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – ) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova Expedition ...

, he took an interest in observing and shooting wildfowl

The Anatidae are the biological family of water birds that includes ducks, geese, and swans. The family has a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring on all the world's continents except Antarctica. These birds are adapted for swimming, floating o ...

at a young age and later took to their breeding.

He established the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust

The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) is an international wildfowl and wetland conservation charity in the United Kingdom.

History

The trust was founded in 1946 by the ornithologist and artist Sir Peter Scott as the Severn Wildfowl Trust. ...

in Slimbridge

Slimbridge is a village and civil parish near Dursley in Gloucestershire, England.

It is best known as the home of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust's Slimbridge Reserve which was started by Sir Peter Scott.

Canal and Patch Bridge

The Glou ...

in 1946 and helped found the World Wide Fund for Nature

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is a Swiss-based international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named th ...

, the logo of which he designed. He was a yachting enthusiast from an early age and took up gliding in mid-life. He was part of the UK team for the 1936 Summer Olympics

The 1936 Summer Olympics (), officially the Games of the XI Olympiad () and officially branded as Berlin 1936, were an international multi-sport event held from 1 to 16 August 1936 in Berlin, then capital of Nazi Germany. Berlin won the bid to ...

and won a bronze medal in sailing a one-man dinghy. He was knighted in 1973 for his work in conservation

Conservation is the preservation or efficient use of resources, or the conservation of various quantities under physical laws.

Conservation may also refer to:

Environment and natural resources

* Nature conservation, the protection and manage ...

of wild animals and was also a recipient of the WWF Gold Medal and the J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize

The J. Paul Getty Award for Conservation Leadership is an annual award recognizing outstanding leadership in global conservation. It was established by J. Paul Getty and has been administered by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) since 2006. The award ...

.

Early life

Scott was born in London at 174,

Scott was born in London at 174, Buckingham Palace Road

Buckingham Palace Road is a street that runs through Victoria, London, from the south side of Buckingham Palace towards Chelsea, London, Chelsea, forming the A3214 road (Great Britain), A3214 road. It is dominated by London Victoria station, V ...

, the only child of Antarctic explorer

This list of Antarctica expeditions is a chronological list of expeditions involving Antarctica. Although the existence of a southern continent had been hypothesized as early as the writings of Ptolemy in the 1st century AD, the South Pole was ...

Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – ) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova Expedition ...

and his wife, Kathleen ( Edith Agnes Kathleen Bruce), a sculptor. He was only two years old when his father died. Robert Scott, in a last letter to his wife, advised her to "make the boy interested in natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

if you can; it is better than games." He was named after Sir Clements Markham

Sir Clements Robert Markham (20 July 1830 – 30 January 1916) was an English geographer, explorer and writer. He was secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) between 1863 and 1888, and later served as the Society's president fo ...

, mentor of Scott's polar expeditions, and a godfather along with J. M. Barrie

Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet, (; 9 May 1860 19 June 1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. He was born and educated in Scotland and then moved to London, where he wrote several succe ...

, creator of Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a fictional character created by Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie. A free-spirited and mischievous young boy who can fly and never grows up, Peter Pan spends his never-ending childhood having adventures on the mythical ...

.

Kathleen Scott remarried in 1922. Her second husband, Hilton Young

Edward Hilton Young, 1st Baron Kennet (20 March 1879 – 11 July 1960) was a British politician and writer.

Family and early life

Young was the youngest son of Sir George Young, 3rd Baronet (see Young baronets), a noted classicist and charit ...

(later Lord Kennet), became stepfather to Peter. In 1923, Peter Scott's half-brother, Wayland Young

Wayland Hilton Young, 2nd Baron Kennet (2 August 1923 – 7 May 2009) was a British writer and politician, notably concerned with planning and conservation. As a Labour minister, he was responsible for setting up the Department of the Environme ...

, was born. Scott was educated at Oundle School

Oundle School is a public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Private schools in the United Kingdom, fee-charging boarding school, boarding and day school) for pupils 11–18 situated in the market town of Oundle in Northamptonshire ...

and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, initially reading Natural Sciences

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

but graduating in the History of Art in 1931. At Cambridge, he shared lodging with John Berry and the two shared many views.

As a student he was also an active member of the Cambridge University Cruising Club The Cambridge University Cruising Club (CUCrC) is an early university sailing club founded on 20 May 1893 - some 9 years after the formation of the Oxford University Yacht Club in 1884. A good short history of the CUCrC is available on the club's w ...

, sailing against Oxford in the 1929 and 1930 Varsity Matches. He studied art at the State Academy in Munich for a year followed by studies at the Royal Academy Schools, London. One of the few non-wildlife paintings that he produced during his career, ''Dinghies Racing on Lake Ontario'', is held by the Cambridge University Cruising Club.

Like his mother, he displayed a strong artistic talent and he became known as a painter of wildlife, particularly birds; he had his first exhibition in London in 1933. His wealthy background allowed him to follow his interests in art, wildlife and many sports, including wildfowling

Waterfowl hunting is the practice of hunting Water bird, aquatic birds such as ducks, geese and other Anseriformes, waterfowls or Wader, shorebirds for sport and meat. Waterfowl are hunted in crop fields where they feed, or in areas with bodies ...

, sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, Windsurfing, windsurfer, or Kitesurfing, kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (Land sa ...

, gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

and ice skating

Ice skating is the Human-powered transport, self-propulsion and gliding of a person across an ice surface, using metal-bladed ice skates. People skate for various reasons, including recreation (fun), exercise, competitive sports, and commuting. ...

. He represented Great Britain and Northern Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

at sailing at the 1936 Summer Olympics

Sailing/Yachting is an Olympic sport starting from the Games of the 1st Olympiad ( 1896 Olympics in Athens, Greece). With the exception of 1904 and the canceled 1916 Summer Olympics, sailing has always been included on the Olympic schedule. Th ...

, winning a bronze medal

A bronze medal in sports and other similar areas involving competition is a medal made of bronze awarded to the third-place finisher of contests or competitions such as the Olympic Games, Commonwealth Games, etc. The outright winner receives ...

in the O-Jolle

The O-Jolle – (Olympiajolle) – was created as the Monotype class for the 1936 Olympic Games by designer Hellmut Wilhelm E. Stauch (GER, later RSA). The boat is a Bermuda rig and the hull was originally carvel - later GRP and cold mould ...

monotype class. He also participated in the Prince of Wales Cup in 1938 during which he and his crew on the ''Thunder and Lightning'' dinghy designed a modified wearable harness (now known as a trapeze

A trapeze is a short horizontal bar hung by ropes, metal straps, or chains, from a ceiling support. It is an aerial apparatus commonly found in circus performances. Trapeze acts may be static, spinning (rigged from a single point), swinging or ...

) that helped them win.

Military service

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Scott served in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) is one of the two volunteer reserve forces of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. Together with the Royal Marines Reserve, they form the Maritime Reserve. The present RNR was formed by merging the original ...

. As a sub-lieutenant, during the failed evacuation of the 51st Highland Division

The 51st (Highland) Division was an infantry division of the British Army that fought on the Western Front in France during the First World War from 1915 to 1918. The division was raised in 1908, upon the creation of the Territorial Force, as ...

he was the British naval officer sent ashore at Saint-Valery-en-Caux

Saint-Valery-en-Caux (, literally ''Saint-Valery in Pays de Caux, Caux'') is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-Maritime Departments of France, department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region in northern France.

The ad ...

in the early hours of 11 June 1940 to evacuate some of the wounded. This was the last evacuation of British troops from the port area of St Valery that was not disrupted by enemy fire.

Then he served in

Then he served in destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s in the North Atlantic but later moved to commanding the First (and only) Squadron of Steam Gun Boats against German E-boats

E-boat was the Western Allies' designation for the fast attack craft (German: ''Schnellboot'', or ''S-Boot'', meaning "fast boat"; plural ''Schnellboote'') of the Kriegsmarine of Nazi Germany during World War II; ''E-boat'' could refer to a pat ...

in the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

.

Scott is credited with designing the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

ship camouflage

Ship camouflage is a form of military deception in which a ship is painted in one or more colors in order to obscure or confuse an enemy's visual observation. Several types of marine camouflage have been used or prototyped: blending or crypsis, ...

scheme, which disguised ship superstructures. In July 1940, he managed to get the destroyer HMS ''Broke'', in which he was serving, experimentally camouflaged, differently on the two sides. To starboard, the ship was painted blue-grey all over, but with white in naturally shadowed areas as countershading

Countershading, or Thayer's law, is a method of camouflage in which animal coloration, an animal's coloration is darker on the top or upper side and lighter on the underside of the body. This pattern is found in many species of mammals, reptile ...

, following the ideas of Abbott Handerson Thayer

Abbott Handerson Thayer (August 12, 1849May 29, 1921) was an American painter, naturalist, and teacher. As a painter of portraits, figures, animals, and landscapes, he enjoyed a certain prominence during his lifetime, and his paintings are repres ...

from the First World War. To port, the ship was painted in "bright pale colours" to combine some disruption of shape with the ability to fade out during the night, again with shadowed areas painted white. However, he later wrote that compromise was fatal to camouflage, and that invisibility at night (by painting ships in white or other pale colours) had to be the sole objective. By May 1941, all ships in the Western Approaches (the North Atlantic) were ordered to be painted in Scott's camouflage scheme. The scheme was said to be so effective that several British ships including HMS ''Broke'' collided with each other. The effectiveness of Scott's and Thayer's ideas was demonstrated experimentally by the Leamington Camouflage Centre in 1941. Under a cloudy overcast sky, the tests showed that a white ship could approach six miles (9.6 km) closer than a black-painted ship before being seen.

On 8 July 1941, it was announced that Scott had been mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

"for good services in rescuing survivors from a burning Vessel" in April 1941 while serving on HMS ''Broke''. On 2 October 1942, it was announced that he had again been mentioned in despatches "for gallantry, daring and skill in the combined attack on Dieppe". He was further mentioned in despatches on 28 September 1943 for an action in the English Channel on 26 July 1943. On 1 June 1943, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

(DSC) "for skill and gallantry in action with enemy light forces" for an action in the English Channel on 15 April 1943 while commanding H.M. Steam Gunboat "Grey Goose". In the ''London Gazette'' of 9 November 1943, he was awarded a Bar to the DSC for actions in the English Channel on the 4th and 27 September 1943 while commanding the First SGB Flotilla. He was appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

in the Military Division (MBE) in the 1942 Birthday Honours

The King's Birthday Honours 1942 were appointments by King George VI to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by members of the British Empire. They were published on 5 June 1942 for the United Kingdom and Canada.

The re ...

.

Postwar life

Scott stood as a

Scott stood as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

in the 1945 general election in Wembley North

Wembley North was a United Kingdom constituencies, parliamentary constituency in what was then the Borough of Wembley in North-West London. It returned one Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) to the House of Commons ...

and narrowly failed to be elected. In 1946, he founded the organisation with which he was ever afterwards closely associated, the Severn Wildfowl Trust (now the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust

The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) is an international wildfowl and wetland conservation charity in the United Kingdom.

History

The trust was founded in 1946 by the ornithologist and artist Sir Peter Scott as the Severn Wildfowl Trust. ...

) with its headquarters at Slimbridge

Slimbridge is a village and civil parish near Dursley in Gloucestershire, England.

It is best known as the home of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust's Slimbridge Reserve which was started by Sir Peter Scott.

Canal and Patch Bridge

The Glou ...

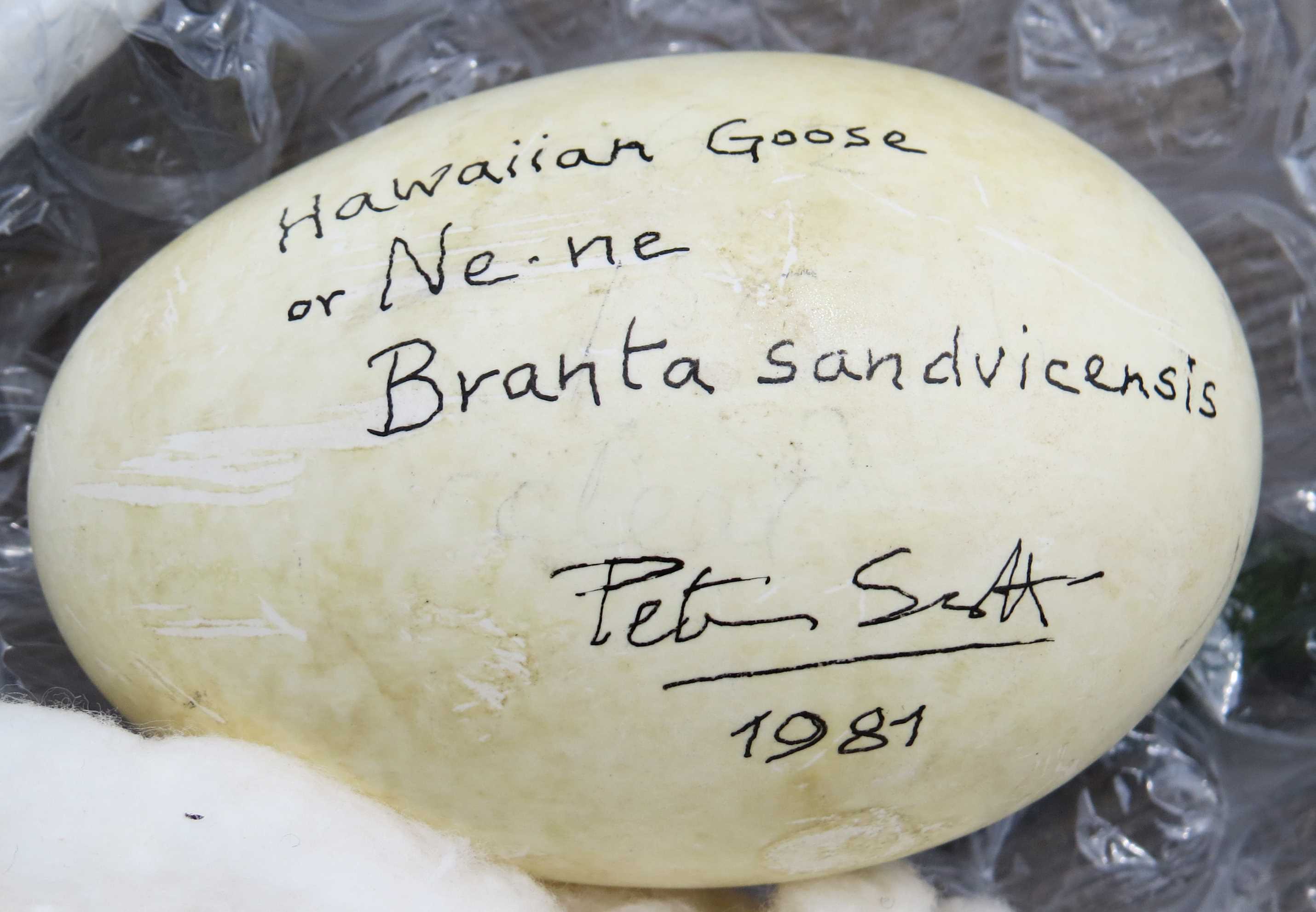

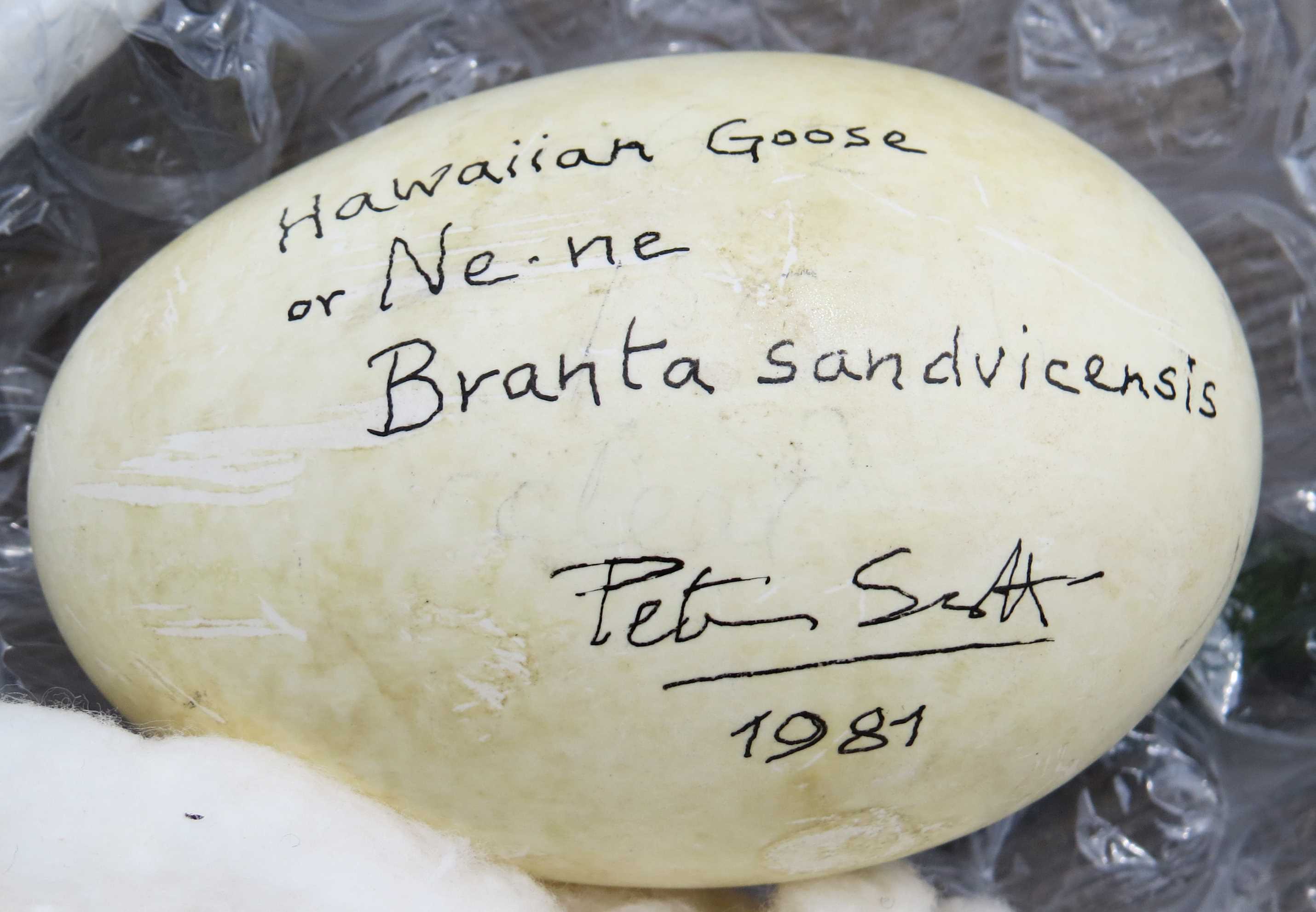

in Gloucestershire. There, through a captive breeding programme, he saved the nene or Hawaiian goose from extinction in the 1950s. In the years that followed, he led ornithological

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

expeditions worldwide, and became a television personality, popularising the study of wildfowl

The Anatidae are the biological family of water birds that includes ducks, geese, and swans. The family has a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring on all the world's continents except Antarctica. These birds are adapted for swimming, floating o ...

and wetlands

A wetland is a distinct semi-aquatic ecosystem whose groundcovers are flooded or saturated in water, either permanently, for years or decades, or only seasonally. Flooding results in oxygen-poor ( anoxic) processes taking place, especially ...

.

His BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

series, ''Look'', ran from 1955 to 1969 and made him a household name. It included the first BBC natural history film to be shown in colour, ''The Private Life of the Kingfisher

"The Private Life of the Kingfisher" is a 1966 television episode of the nature series '' Look'', was the first BBC natural history film to be shown in colour.

Depicting a pair of common kingfishers at their underground nest on the River Test in ...

'' (1968), which he narrated. He wrote and illustrated several books on the subject, including his autobiography, ''The Eye of the Wind'' (1961). In the 1950s, he also appeared regularly on BBC radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927. The service provides national radio stations cove ...

's ''Children's Hour

''Children's Hour'', initially ''The Children's Hour'', was the BBC's principal recreational service for children (as distinct from "Broadcasts to Schools") which began during the period when radio was the only medium of broadcasting.

''Childre ...

'', in the series, "Nature Parliament".

In the early 1950s, his designs were used on a range of tableware, "Wild Geese", by Midwinter Pottery

The Midwinter Pottery was founded as W. R. Midwinter by William Robinson Midwinter in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent in 1910 and had become one of England's largest potteries by the late 1930s with more than 700 employees. Production of Midwinter pot ...

.

Scott took up gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

in 1956 and became a British champion in 1963. He was chairman of the British Gliding Association

The British Gliding Association (BGA) is the governing body for gliding in the United Kingdom.

Gliding in the United Kingdom operates through 80 gliding clubs (both civilian and service) which have 2,310 gliders and 9,462 full flying members (i ...

(BGA) for two years from 1968 and was president of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Gliding Club. He was responsible for involving Prince Philip

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 19219 April 2021), was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he was the consort of the British monarch from h ...

in gliding.

He was the subject of '' This Is Your Life'' in 1956 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews

Eamonn Andrews, (19 December 1922 – 5 November 1987) was an Irish radio and television presenter, employed primarily in the United Kingdom from the 1950s to the 1980s. From 1960 to 1964 he chaired the Radio Éireann Authority (now the RTÉ ...

at the King's Theatre, Hammersmith

King's Theatre was a live entertainment venue in Hammersmith, West London, on the corner of Hammersmith Road and Rowan Road. It was built in 1902 as a music hall, with a seating capacity of 3,000.

History

The theatre was designed by W. G. R. Sprag ...

, London.

As a member of the

As a member of the Species Survival Commission

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

of the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

, he helped create the Red Data books

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological spe ...

, the group's lists of endangered species.

Scott was the founder President of the Society of Wildlife Artists

The Society of Wildlife Artists (SWLA) is a British organisation for artists who paint or draw wildlife. It was founded in 1964. Its founder president was Sir Peter Scott, the current president of the society is British artist Harriet Mead.

The s ...

and President of the Nature in Art

Nature in Art is a museum and art gallery at Wallsworth Hall, Twigworth, Gloucester, England, dedicated exclusively to art inspired by nature in all forms, styles and media. The museum has twice been specially commended in the National Heritag ...

Trust (a role in which his wife Philippa succeeded him). Scott tutored numerous artists including Paul Karslake

Paul Karslake FRSA (1958 – 23 March 2020) was a British artist, primarily a painter.

Early life

Karslake was born in Basildon, Essex.

.

From 1973 to 1983, Scott was Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

of the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university in Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingham (founded in 1825 as ...

. In 1979, he was awarded an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Science) from the University of Bath

The University of Bath is a public research university in Bath, England. Bath received its royal charter in 1966 as Bath University of Technology, along with a number of other institutions following the Robbins Report. Like the University ...

.

Scott continued with his love of sailing, skippering the 12 Metre

The 12 Metre class is a rating class for racing sailboats that are designed to the International rule. It enables fair competition between boats that rate in the class whilst retaining the freedom to experiment with the details of their designs. ...

yacht

A yacht () is a sail- or marine propulsion, motor-propelled watercraft made for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a ...

''Sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

'' in the 1964 challenge for the America's Cup

The America's Cup is a sailing competition and the oldest international competition still operating in any sport. America's Cup match races are held between two sailing yachts: one from the yacht club that currently holds the trophy (known ...

which was held by the United States. ''Sovereign'' suffered a whitewash 4–0 defeat in a one-sided competition where the American boat was of a noticeably faster design. From 1955 to 1969 he was the president of the International Yacht Racing Union

World Sailing is the international sports governing body for sailing; it is recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Paralympic Committee (IPC).

History

The creation of the International Yacht Racing Union ( ...

(now World Sailing).

He was one of the founders of the World Wide Fund for Nature

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is a Swiss-based international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named th ...

(WWF, formerly called the World Wildlife Fund), and designed its panda

The giant panda (''Ailuropoda melanoleuca''), also known as the panda bear or simply panda, is a bear species endemic to China. It is characterised by its white coat with black patches around the eyes, ears, legs and shoulders. Its body is ...

logo. His pioneering work in conservation also contributed greatly to the shift in policy of the International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation ...

and signing of the Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antarctic comprises the continent of A ...

, the latter inspired by his visit to his father's base on Ross Island

Ross Island is an island in Antarctica lying on the east side of McMurdo Sound and extending from Cape Bird in the north to Cape Armitage in the south, and a similar distance from Cape Royds in the west to Cape Crozier in the east.

The isl ...

in Antarctica. In 1986 he received the WWF Gold Medal. In the same year he received the J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize

The J. Paul Getty Award for Conservation Leadership is an annual award recognizing outstanding leadership in global conservation. It was established by J. Paul Getty and has been administered by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) since 2006. The award ...

for his role as cofounder of WWF and his life-long contributions to saving endangered wildlife.

Scott was a long-time vice-president of the British Naturalists' Association

The British Naturalists' Association (BNA), founded in 1905 by E. Kay Robinson as the British Empire Naturalists' Association (BENA), is an organization in the United Kingdom to promote the study of natural history. It publishes a journal called ...

, whose Peter Scott Memorial Award was instituted after his death, to commemorate his achievements.

He died of a heart attack on 29 August 1989 in Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

, at age 79.

Documentaries

Scott narrated ''Wild Wings

''Wild Wings'' is a 1966 British short documentary film directed by Patrick Carey and John Taylor and produced by British Transport Films. In 1966, it won an Oscar for Best Short Subject at the 39th Academy Awards.

Summary

The film looks a ...

'', a 1966 British short documentary film

A documentary film (often described simply as a documentary) is a nonfiction Film, motion picture intended to "document reality, primarily for instruction, education or maintaining a Recorded history, historical record". The American author and ...

, produced by British Transport Films

British Transport Films was an organisation set up in 1949 to make documentary films on the general subject of British transport. Its work included internal training films, travelogues (extolling the virtues of places that could be visited via t ...

. In 1967, it won an Oscar

Oscar, OSCAR, or The Oscar may refer to:

People and fictional and mythical characters

* Oscar (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters named Oscar, Óscar or Oskar

* Oscar (footballer, born 1954), Brazilian footballer ...

for Best Short Subject at the 39th Academy Awards

The 39th Academy Awards, honoring the best in film for 1966, were held on April 10, 1967, hosted by Bob Hope at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in Santa Monica, California.

The Academy Awards broadcast faced the threat of cancellation due ...

.

In August 1986, an ITV Special was transmitted by Central Independent Television

ITV Central, previously known as Central Independent Television, Carlton Central, ITV1 for Central England and commonly referred to as simply Central, is the ITV (TV network), Independent Television franchisee in Midlands, the English Midlands ...

(Production No.6407) on Scott entitled ''Interest the Boy in Nature'' featuring Konrad Lorenz

Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (Austrian ; 7 November 1903 – 27 February 1989) was an Austrian zoology, zoologist, ethology, ethologist, and ornithologist. He shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von ...

, Prince Philip, David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and writer. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Studios Natural History Unit, the nine nature d ...

and Gerald Durrell

Gerald Malcolm Durrell Order of the British Empire, OBE (7 January 1925 – 30 January 1995) was a British naturalist, writer, zookeeper, conservation movement, conservationist, and television presenter. He was born in Jamshedpur in British Ind ...

; written, produced and directed by Robin Brown.

In 1996 Scott's life and work in wildlife conservation was celebrated in a major BBC ''Natural World'' documentary, produced by Andrew Cooper and narrated by Sir David Attenborough. Filmed across three continents from Hawaii to the Russian arctic, ''In the Eye of the Wind'' was the BBC Natural History Unit

The BBC Studios Natural History Unit (NHU) is a department of BBC Studios that produces television, radio and online content with a natural history or wildlife theme. It is best known for its highly regarded nature documentaries, including '' T ...

's tribute to Scott and the organisation he founded, the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust, on its 50th anniversary.

In June 2004, Scott and Sir David Attenborough were jointly profiled in the second of a three-part BBC Two

BBC Two is a British free-to-air Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom, public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's second flagship channel, and it covers a wide range of subject matte ...

series, ''The Way We Went Wild

''The Way We Went Wild'' is a three-part BBC TV series, first shown on BBC Two, about British wildlife presenters. It was narrated by Josette Simon.

Episode 1

Episode 1, screened on 13 June 2004, featured Johnny Morris and Bill Oddie.

Episode ...

'', about television wildlife presenters and were described as being largely responsible for the way that the British and much of the world view wildlife.

Scott's life was also the subject of a BBC Four

BBC Four is a British free-to-air Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom, public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It was launched on 2 March 2002

documentary called ''Peter Scott – A Passion for Nature'' produced in 2006 by Available Light Productions (Bristol).

Loch Ness Monster

In 1962, he co-founded the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau with Conservative MPDavid James Dewi, Dai, Dafydd or David James may refer to:

Performers

*David James (actor, born 1839) (1839–1893), English stage comic and a founder of London's Vaudeville Theatre

*David James (actor, born 1967) (born 1967), Australian presenter of ABC's ''P ...

, who had previously been Polar Adviser on the 1948 film '' Scott of the Antarctic'', based on his father's polar expedition. In 1975 Scott proposed the scientific name

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin gramm ...

''Nessiteras rhombopteryx'' for the Loch Ness Monster

The Loch Ness Monster (), known affectionately as Nessie, is a mythical creature in Scottish folklore that is said to inhabit Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands. It is often described as large, long-necked, and with one or more humps protrud ...

(based on a blurred underwater photograph of a supposed fin) so that it could be registered as an endangered species. The name was based on the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

for "monster of Ness

Ness or NESS may refer to:

Places Australia

* Ness, Wapengo, a heritage-listed natural coastal area in New South Wales

United Kingdom

* Ness, Cheshire, England, a village

* Ness, Lewis, the most northerly area on Lewis, Scotland, UK

* Cuspate ...

with diamond-shaped fin", but it was later pointed out by ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' to be an anagram

An anagram is a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase, typically using all the original letters exactly once. For example, the word ''anagram'' itself can be rearranged into the phrase "nag a ram"; which ...

of "Monster hoax by Sir Peter S". Robert H. Rines

Robert Harvey Rines (August 30, 1922November 1, 2009) was an American lawyer, inventor, musician, and composer. He is perhaps best known for his efforts to find and identify the Loch Ness Monster.

Biography

Rines was born August 30, 1922, in Bos ...

, who took two supposed pictures of the monster in the 1970s, responded by pointing out that the letters could also be read as an anagram for, "Yes, both pix are monsters, R."

Personal life

Scott married the novelistElizabeth Jane Howard

Elizabeth Jane Howard (26 March 1923 – 2 January 2014), was an English novelist. She wrote 12 novels including the best-selling series ''The'' ''Cazalet Chronicle''.

Early life

Howard's father was Major David Liddon Howard (1896–1958), a ...

in 1942 and had a daughter, Nicola, born a year later. Howard left Scott in 1946 and they were divorced in 1951.Elizabeth Jane Howard. ''Slipstream'', Macmillan, 2002, page 219

In 1951, Scott married his assistant, Philippa Talbot-Ponsonby, while on an expedition to Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

in search of the breeding grounds of the pink-footed goose

The pink-footed goose (''Anser brachyrhynchus'') is a goose which breeds in eastern Greenland, Iceland, Svalbard, and recently Novaya Zemlya. It is migratory, wintering in northwest Europe, especially Ireland, Great Britain, the Netherlands, a ...

. A daughter, Dafila, was born later in the same year (''dafila'' is the old scientific name

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin gramm ...

for a pintail). She, too, became an artist, painting birds. A son, Falcon, was born in 1954.

Scott shared a nanny

A nanny is a person who provides child care. Typically, this care is given within the children's family setting. Throughout history, nannies were usually servants in large households and reported directly to the lady of the house. Today, modern ...

(Enid) with Nigel Hadow and his son Pen Hadow

Rupert Nigel Pendrill Hadow, known as Pen Hadow (born 26 February 1962), is a British Arctic region explorer, advocate, adventurer and guide. He is the only person to have trekked solo, and without resupply by third parties, from Canada to the ...

.

Civilian honours

Having been appointed a military MBE in the1942 Birthday Honours

The King's Birthday Honours 1942 were appointments by King George VI to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by members of the British Empire. They were published on 5 June 1942 for the United Kingdom and Canada.

The re ...

, he was promoted to Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

in the Civil Division (CBE) in the 1953 Coronation Honours

The 1953 Coronation Honours were appointments by Queen Elizabeth II to various orders and honours on the occasion of her coronation on 2 June 1953. The honours were published in '' The London Gazette'' on 1 June 1953.New Zealand list:

The rec ...

. Having been appointed a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised Order of chivalry, orders of chivalry; it is a part of the Orders, decorations, and medals ...

in the 1973 New Year Honours

The New Year Honours 1973 were appointments in many of the Commonwealth realms of Queen Elizabeth II to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. They were announced on 1 January 1973 to celebr ...

for services to conservation and the environment, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

during a ceremony at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

on 27 February 1973. In the 1987 Birthday Honours

Queen's Birthday Honours are announced on or around the date of the Queen's Official Birthday in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. The dates vary, both from year to year and from country to country. All are published in sup ...

, he was appointed to the Order of the Companions of Honour

The Order of the Companions of Honour is an Order (distinction), order of the Commonwealth realms. It was founded on 4 June 1917 by King George V as a reward for outstanding achievements. It was founded on the same date as the Order of the Brit ...

as a Member (CH) "for services to conservation". In 1987 he was also elected Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

Legacy

The fish Scotts' wrasse ''Cirrhilabrus scottorum'' was named after Peter and Philippa Scott for their “great contribution in nature conservation". The ''Peter Scott Walk'' passes the mouth of theRiver Nene

The River Nene ( or ) flows through the counties of Northamptonshire, Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, and Norfolk in Eastern England from its sources in Arbury Hill in Northamptonshire. Flowing Northeast through East England to its mouth at Lutt ...

and follows the old sea bank along The Wash

The Wash is a shallow natural rectangular bay and multiple estuary on the east coast of England in the United Kingdom. It is an inlet of the North Sea and is the largest multiple estuary system in the UK, as well as being the largest natural ba ...

, from Scott's lighthouse near Sutton Bridge

Sutton Bridge is a town and civil parish in the South Holland district of Lincolnshire, England. It is situated on the A17 road, north from Wisbech and west from King's Lynn. The village includes a commercial dock on the west bank of the ...

in Lincolnshire to the ferry crossing at King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is north-east of Peterborough, north-north-east of Cambridg ...

.

The ''Sir Peter Scott National Park'' is located in central Jamnagar

Jamnagar () is a city and the headquarters of Jamnagar district in the Indian state of Gujarat. The city lies just to the south of the Gulf of Kutch, some west of the state capital, Gandhinagar. The city was the capital of Nawanagar State, Na ...

, in Gujarat, India. Jamnagar also has a ''Sir Peter Scott Bird Hospital''. These institutions in Jamnagar were founded as a result of the friendship between Peter Scott and Jam Sahib, the Indian ruler of Jamnagar.

Bibliography

* ''Morning flight.'' Country Life, London 1936–44. * ''Wild chorus.'' Country Life, London 1939. * ''Through the Air.'' (with Michael Bratby). Country Life, London 1941. * ''The battle of the narrow seas.'' Country Life, White Lion & Scribners, London, New York 1945–74. * ''Portrait drawings.'' Country Life, London 1949. * ''Key to the wildfowl of the world.'' Slimbridge 1950. * ''Wild geese and Eskimos.'' Country Life & Scribner, London, New York 1951. * ''A thousand geese.'' Collins, Houghton & Mifflin, London, Boston 1953/54. * ''A coloured key to the wildfowl of the world.'' Royle & Scribner, London, New York 1957–88. * ''Wildfowl of the British Isles.'' Country Life, London 1957. * ''The eye of the wind.'' (autobiography) Hodder, Stoughton & Brockhampton, London, Leicester 1961–77. , * ''Animals in Africa.'' Potter & Cassell, New York, London 1962–65. * ''My favourite stories of wild life.'' Lutterworth 1965. * ''Our vanishing wildlife.'' Doubleday, Garden City 1966. * ''Happy the man.'' Sphere, London 1967. * ''Atlas en couleur des anatidés du monde.'' Le Bélier-Prisma, Paris 1970. * ''The wild swans at Slimbridge.'' Slimbridge 1970. * ''The swans.'' Joseph, Houghton & Mifflin, London, Boston 1972. * ''The amazing world of animals.'' Nelson, Sunbury-on-Thames 1976. * ''Observations of wildlife.'' Phaidon & Cornell, Oxford, Ithaca 1980. , , * ''Travel diaries of a naturalist.'' Collins, London. 3 vols: 1983, 1985, 1987. , , * ''The crisis of the University.''Croom Helm

Routledge ( ) is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, an ...

, London 1984. ,

* ''Conservation of island birds.'' Cambridge 1985.

* ''The art of Peter Scott.'' Sinclair-Stevenson

Sinclair-Stevenson Ltd was a British publisher founded in 1989 by Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson.

Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson became an editor at Hamish Hamilton

Hamish Hamilton Limited is a publishing imprint and originally a British p ...

, London 1992 p. m.

Forewords

* ''The Red Book – Wildlife in Danger'' James Fisher, Noel Simon &Jack Vincent

Jack Vincent (6 March 1904 – 3 July 1999) was an English ornithologist.

Biography

Vincent was born in London. At age 21 he moved to South Africa where he worked on two farms in the Richmond district of the Natal Province. In the 1920s he we ...

, Collins, 1969

** The acknowledgments in this book credit Scott with originating the idea behind it

* ''George Edward Lodge – Unpublished Bird Paintings'' C.A. Fleming ( Michael Joseph) 1983

Illustrations

* * ''Waterfowl of the World'' – with Jean Delacour, Country Life 1954 * Gallico, Paul (1946), '' The Snow Goose'', Michael Joseph, London. Four full-page colour paintings, plus numerous black-and-white line drawings.Films

* ''Wild Wings

''Wild Wings'' is a 1966 British short documentary film directed by Patrick Carey and John Taylor and produced by British Transport Films. In 1966, it won an Oscar for Best Short Subject at the 39th Academy Awards.

Summary

The film looks a ...

'' (1966), narrator

References

Autobiography

*Further reading

* ''The Wild Geese of the Newgrounds'' by Paul Walkden. Published by the Friends of WWT Slimbridge, 2009. . Illustrated with colour plates and ink drawing by Peter Scott. Includes chronology. * ''Peter Scott. Collected Writings 1933–1989''. Compiled by Paul Walkden. Published by The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust 2016. Hardback , E-book . Includes Chronology and Bibliography. Illustrated with photos and b/w illustrations.External links

Article illustrated with his paintings

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Scott, Peter 1909 births 1989 deaths English ornithologists British conservationists English activists Cryptozoologists English television presenters Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust English illustrators 20th-century English painters English male painters 20th-century English writers Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) British stamp designers English male sailors (sport) Sailors at the 1936 Summer Olympics – O-Jolle Olympic sailors for Great Britain Olympic bronze medallists for Great Britain 1964 America's Cup sailors Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Knights Bachelor Anglo-Scots Chancellors of the University of Birmingham Rectors of the University of Aberdeen Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge People educated at West Downs School People educated at Oundle School English people of Scottish descent English conservationists British bird artists Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War II Olympic medalists in sailing Camoufleurs 20th-century British zoologists Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Medalists at the 1936 Summer Olympics Scott family (conservationists), Peter Presidents of World Sailing English sports executives and administrators Military personnel from the City of Westminster 20th-century English male artists 20th-century English sportsmen Fellows_of_the_Zoological_Society_of_London