Peter Keating (biologist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Fountainhead'' is a 1943 novel by Russian-American author

Rand's stated goal in writing fiction was to portray her vision of an ideal man. The character of Howard Roark, the

Rand's stated goal in writing fiction was to portray her vision of an ideal man. The character of Howard Roark, the

Dominique Francon is the heroine of ''The Fountainhead'', described by Rand as "the woman for a man like Howard Roark". Rand described Dominique as similar to herself "in a bad mood". For most of the novel, the character operates from a mistaken belief that a corrupt world will destroy the things she values. Believing that the values she admires cannot survive in the real world, she chooses to turn away from them so that the world cannot harm her. Only at the end of the novel does she accept that she can be happy and survive.

Dominique Francon is the heroine of ''The Fountainhead'', described by Rand as "the woman for a man like Howard Roark". Rand described Dominique as similar to herself "in a bad mood". For most of the novel, the character operates from a mistaken belief that a corrupt world will destroy the things she values. Believing that the values she admires cannot survive in the real world, she chooses to turn away from them so that the world cannot harm her. Only at the end of the novel does she accept that she can be happy and survive.

Ellsworth Monkton Toohey is Roark's antagonist. He is Rand's personification of evilthe most active and self-aware villain in any of her novels. Toohey is a socialist and represents the spirit of collectivism more generally. He styles himself as representative of the will of the masses but his actual desire is for power over others. He controls individual victims by destroying their sense of self-worth and seeks broader power (over "the world", as he declares to Keating in a moment of candor) by promoting the ideals of

Ellsworth Monkton Toohey is Roark's antagonist. He is Rand's personification of evilthe most active and self-aware villain in any of her novels. Toohey is a socialist and represents the spirit of collectivism more generally. He styles himself as representative of the will of the masses but his actual desire is for power over others. He controls individual victims by destroying their sense of self-worth and seeks broader power (over "the world", as he declares to Keating in a moment of candor) by promoting the ideals of

Rand chose the profession of architecture as the background for her novel, although she knew nothing about the field beforehand.Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In As a field that combines art, technology, and business, it allowed her to illustrate her primary themes in multiple areas. Rand later wrote that architects provide "both art and a basic need of men's survival". In a speech to a chapter of the

Rand chose the profession of architecture as the background for her novel, although she knew nothing about the field beforehand.Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In As a field that combines art, technology, and business, it allowed her to illustrate her primary themes in multiple areas. Rand later wrote that architects provide "both art and a basic need of men's survival". In a speech to a chapter of the

Although Rand had some mainstream success previously with her play ''

Although Rand had some mainstream success previously with her play ''

The Dutch theater company

The Dutch theater company

Annual ''The Fountainhead'' essay contest

(Ayn Rand Institute)

CliffsNotes for ''The Fountainhead''

Panel discussion about "The Relevance of ''The Fountainhead'' in Today's World" on May 12, 2002

from

Ayn Rand

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum; , 1905March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and philosopher. She is known for her fiction and for developing a philosophical system which s ...

, her first major literary success. The novel's protagonist, Howard Roark, is an intransigent young architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

who battles against conventional standards and refuses to compromise with an architectural establishment unwilling to accept innovation. Roark embodies what Rand believed to be the ideal man, and his struggle reflects Rand's belief that individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

is superior to collectivism

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struct ...

.

Roark is opposed by what he calls "second-handers", who value conformity over independence and integrity. These include Roark's former classmate, Peter Keating, who succeeds by following popular styles but turns to Roark for help with design problems. Ellsworth Toohey, a socialist architecture critic Architecture criticism is the critique of architecture. Everyday criticism relates to published or broadcast critiques of buildings, whether completed or not, both in terms of news and other criteria. In many cases, criticism amounts to an assessmen ...

who uses his influence to promote his political and social agenda, tries to destroy Roark's career. Tabloid newspaper publisher Gail Wynand seeks to shape popular opinion; he befriends Roark, then betrays him when public opinion turns in a direction he cannot control. The novel's most controversial character is Roark's lover, Dominique Francon. She believes that non-conformity has no chance of winning, so she alternates between helping Roark and working to undermine him.

Twelve publishers rejected the manuscript before an editor at the Bobbs-Merrill Company

The Bobbs-Merrill Company was an American book publisher active from 1850 until 1985, and located in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Company history

The Bobbs-Merrill Company began in 1850 October 3 when Samuel Merrill bought an Indianapolis bookstore ...

risked his job to get it published. Contemporary reviewers' opinions were polarized. Some praised the novel as a powerful paean to individualism, while others thought it overlong and lacking sympathetic characters. Initial sales were slow, but the book gained a following by word of mouth and became a bestseller

A bestseller is a book or other media noted for its top selling status, with bestseller lists published by newspapers, magazines, and book store chains. Some lists are broken down into classifications and specialties (novel, nonfiction book, cookb ...

. More than 10 million copies of ''The Fountainhead'' have been sold worldwide, and it has been translated into more than 30 languages. The novel attracted a new following for Rand and has enjoyed a lasting influence, especially among architects, entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurship is the creation or extraction of economic value in ways that generally entail beyond the minimal amount of risk (assumed by a traditional business), and potentially involving values besides simply economic ones.

An entreprene ...

, American conservatives

Conservatism in the United States is one of two major political ideologies in the United States, with the other being liberalism. Traditional American conservatism is characterized by a belief in individualism, traditionalism, capitalism, re ...

, and libertarians

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

.

The novel has been adapted into other media several times. An illustrated version was syndicated in newspapers in 1945. Warner Bros.

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (WBEI), commonly known as Warner Bros. (WB), is an American filmed entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California and the main namesake subsidiary of Warner Bro ...

produced a film version in 1949; Rand wrote the screenplay, and Gary Cooper

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, silent screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, ...

played Roark. Critics panned the film, which did not recoup its budget; several directors and writers have considered developing a new film adaptation. In 2014, Belgian theater director Ivo van Hove

Ivo van Hove (born 28 October 1958) is a Belgian theatre director. He is known for his Off-Broadway avant-garde experimental theatre productions. For over twenty years, he served as the director of the Toneelgroep Amsterdam. On Broadway, he has d ...

created a stage adaptation, which received mixed reviews.

Plot

In early 1922, Howard Roark is expelled from the architecture department of the Stanton Institute of Technology because he has not adhered to the school's preference for historical convention in building design. Roark goes toNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and gets a job with Henry Cameron. Cameron was once a renowned architect, but now gets few commissions. In the meantime, Roark's popular but vacuous fellow student and housemate Peter Keating (whom Roark sometimes helped with projects) graduates with high honors. He too moves to New York, where he has been offered a position with the prestigious architecture firm, Francon & Heyer. Keating ingratiates himself with Guy Francon and works to remove rivals among his coworkers. After Francon's partner, Lucius Heyer, suffers a fatal stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

brought on by Keating's antagonism, Francon chooses Keating to replace him. Meanwhile, Roark and Cameron create inspired work, but struggle financially.

After Cameron retires, Keating hires Roark, whom Francon soon fires for refusing to design a building in the classical style. Roark works briefly at another firm, then opens his own office but has trouble finding clients and closes it down. He gets a job in a granite quarry owned by Francon. There he meets Francon's daughter Dominique, a columnist for ''The New York Banner'', while she is staying at her family's estate nearby. They are immediately attracted to each other, leading to a rough sexual encounter that Dominique later calls a rape. Shortly after, Roark is notified that a client is ready to start a new building, and he returns to New York. Dominique also returns to New York and learns that Roark is an architect. She attacks his work in public, but visits him for secret sexual encounters.

Ellsworth M. Toohey, who writes a popular architecture column in the ''Banner'', is an outspoken socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

who shapes public opinion through his column and a circle of influential associates. Toohey sets out to destroy Roark through a smear campaign. He recommends Roark to Hopton Stoddard, a wealthy acquaintance who wants to build a Temple of the Human Spirit. Roark's unusual design includes a nude statue modeled on Dominique; Toohey persuades Stoddard to sue Roark for malpractice. Toohey and several architects (including Keating) testify at the trial that Roark is incompetent as an architect for his rejection of historical styles. Dominique also argues for the prosecution in tones that can be interpreted to be speaking more in Roark's defense than for the plaintiff, but he loses the case. Dominique decides that since she cannot have the world she wants, in which men like Roark are recognized for their greatness, she will live entirely in the world she has, which shuns Roark and praises Keating. She marries Keating and turns herself over to him, doing and saying whatever he wants, and actively persuading potential clients to hire him instead of Roark.

To win Keating a prestigious commission offered by Gail Wynand, the owner and editor-in-chief of the ''Banner'', Dominique agrees to sleep with Wynand. Wynand is so strongly attracted to Dominique that he pays Keating to divorce her, after which Wynand and Dominique marry. Wanting to build a home for himself and his new wife, Wynand discovers that Roark designed every building he likes and so hires him. Roark and Wynand become close friends; Wynand is unaware of Roark's past relationship with Dominique.

Washed up and out of the public eye, Keating pleads with Toohey to use his influence to get the commission for the much-sought-after Cortlandt housing project. Keating knows his most successful projects were aided by Roark, so he asks for Roark's help in designing Cortlandt. Roark agrees in exchange for complete anonymity and Keating's promise that it will be built exactly as designed. After taking a long vacation with Wynand, Roark returns to find that Keating was not able to prevent major changes from being made in Cortlandt's construction. Roark dynamites the project to prevent the subversion of his vision.

Roark is arrested and his action is widely condemned, but Wynand decides to use his papers to defend his friend. This unpopular stance hurts the circulation of his newspapers, and Wynand's employees go on strike after Wynand dismisses Toohey for disobeying him and criticizing Roark. Faced with the prospect of closing the paper, Wynand gives in and publishes a denunciation of Roark. At his trial, Roark makes a lengthy speech about the value of ego and integrity, and he is found not guilty. Dominique leaves Wynand for Roark. Wynand, who has betrayed his own values by attacking Roark, finally grasps the nature of the power he thought he held. He shuts down the ''Banner'' and commissions a final building from Roark, a skyscraper that will serve as a monument to human achievement. Eighteen months later, the Wynand Building is under construction. Dominique, now Roark's wife, enters the site to meet him atop its steel framework.

Major characters

Howard Roark

Rand's stated goal in writing fiction was to portray her vision of an ideal man. The character of Howard Roark, the

Rand's stated goal in writing fiction was to portray her vision of an ideal man. The character of Howard Roark, the protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a ...

of ''The Fountainhead'', was the first instance where she believed she had achieved this. Roark embodies Rand's egoistic

Egoism is a philosophy concerned with the role of the self, or , as the motivation and goal of one's own action. Different theories of egoism encompass a range of disparate ideas and can generally be categorized into descriptive or normative ...

moral ideals, especially the virtues of independence and integrity.

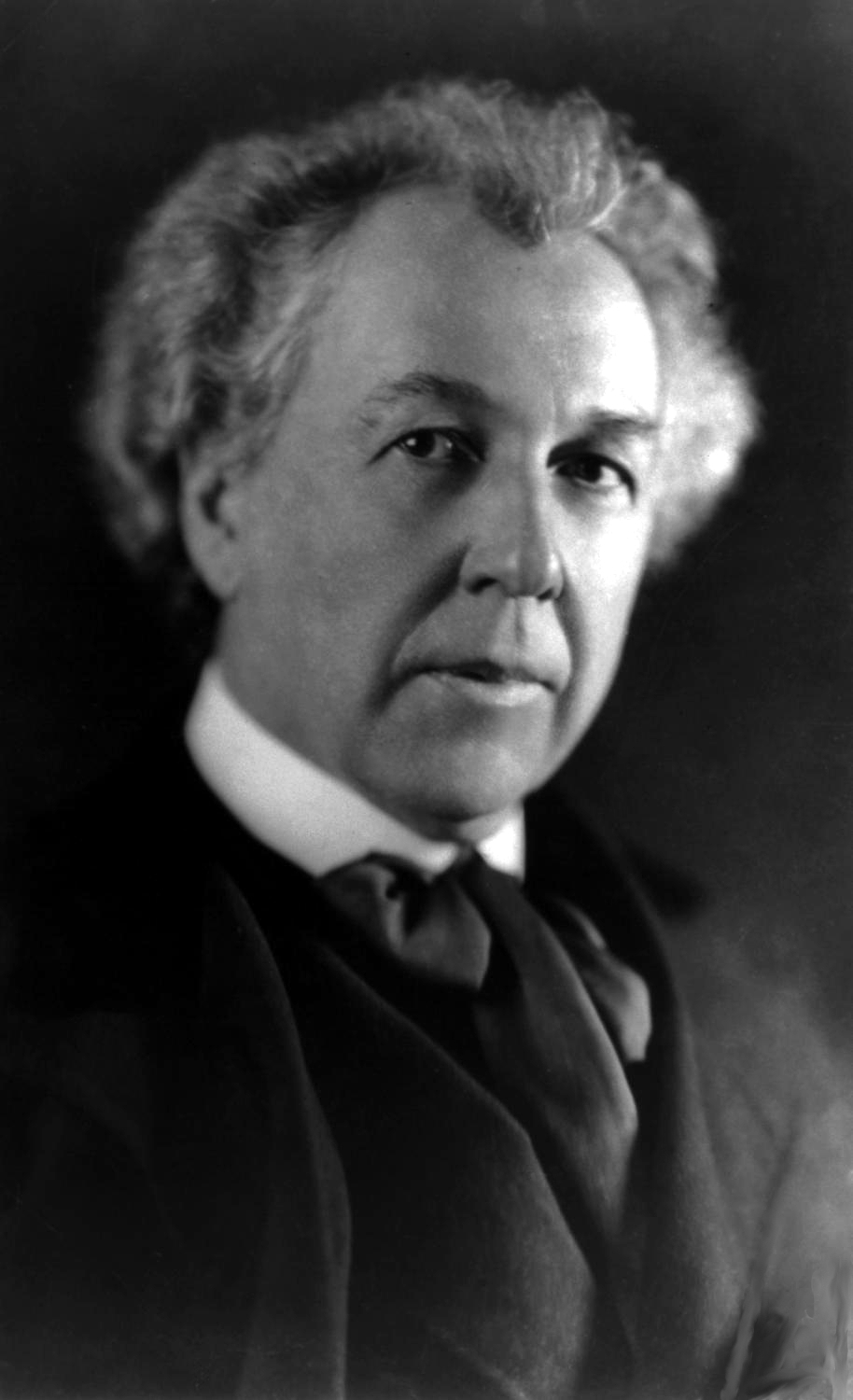

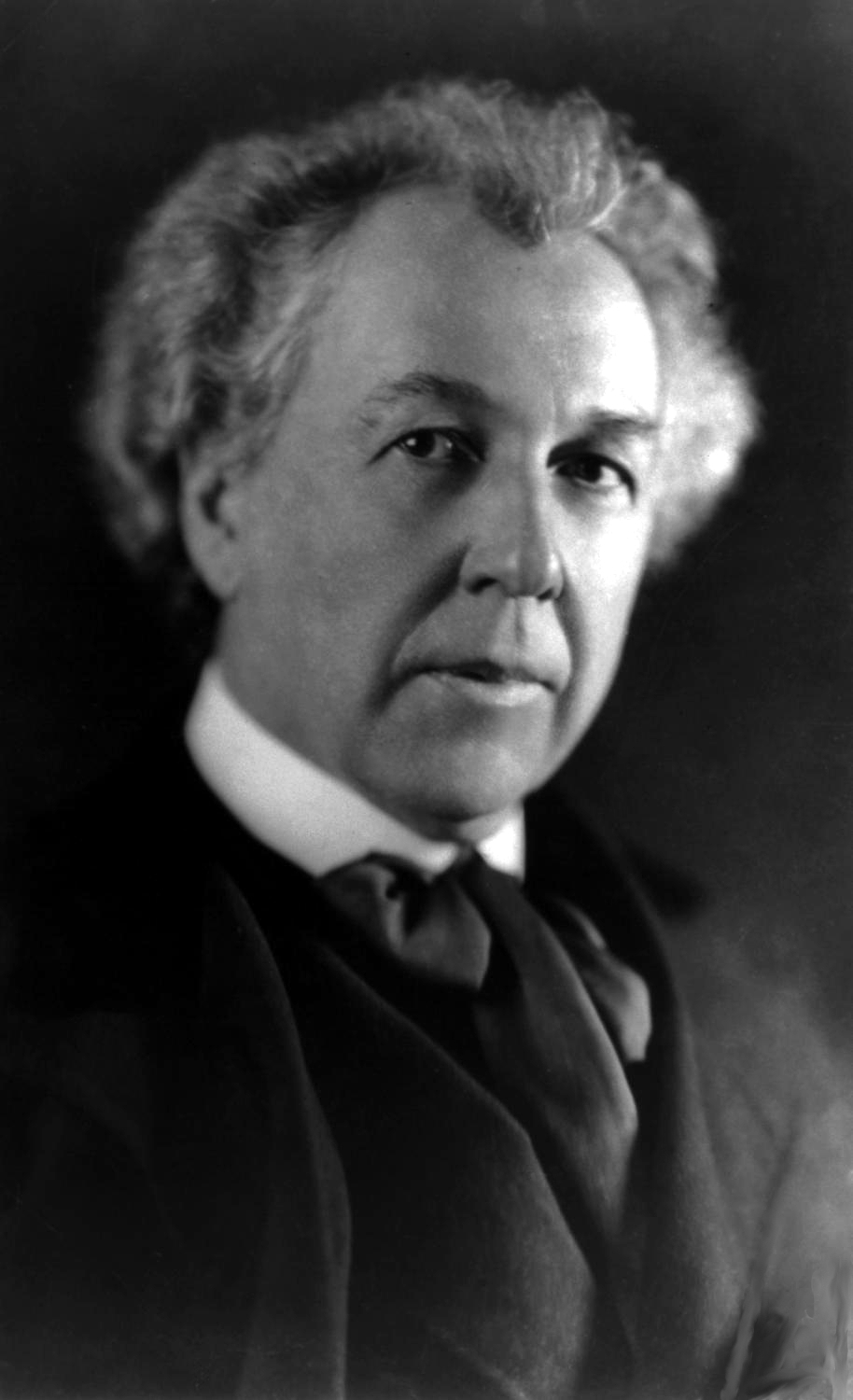

The character of Roark was at least partly inspired by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed List of Frank Lloyd Wright works, more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key ...

. Rand described the inspiration as limited to specific ideas he had about architecture and "the pattern of his career". She denied that Wright had anything to do with the philosophy expressed by Roark or the events of the plot. Rand's denials have not stopped commentators from claiming stronger connections between Wright and Roark. Wright equivocated about whether he thought Roark was based on him, sometimes implying that he did, at other times denying it. Wright biographer Ada Louise Huxtable

Ada Louise Huxtable (née Landman; March 14, 1921 – January 7, 2013) was an American architecture critic and writer on architecture. Huxtable established architecture and urban design journalism in North America and raised the public's awarene ...

described significant differences between Wright's philosophy and Rand's and quoted him, declaring, "I deny the paternity and refuse to marry the mother." Architecture critic Martin Filler

Martin Myles Filler (born September 17, 1948) is an American architecture critic. He is best known for his long essays on modern architecture that have appeared in ''The New York Review of Books'' since 1985, and which served as the basis for his ...

said that Roark resembles the Swiss-French modernist architect Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , ; ), was a Swiss-French architectural designer, painter, urban planner and writer, who was one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture ...

more closely than Wright.

Peter Keating

In contrast to the individualistic Roark, Peter Keating is aconformist

Conformity or conformism is the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to social group, group norms, politics or being like-minded. Social norm, Norms are implicit, specific rules, guidance shared by a group of individuals, that guide t ...

who bases his choices on what others want. Introduced to the reader as Roark's classmate in architecture school, two years ahead of him, Keating does not really want to be an architect. He loves painting, but his mother steers him toward architecture instead.Smith, Tara. "Unborrowed Vision: Independence and Egoism in ''The Fountainhead''". In In this, as in all his decisions, Keating does what others expect rather than follow his personal interests. He becomes a social climber

A ''parvenu'' is a person who is a relative newcomer to a high-ranking socioeconomic class. The word is borrowed from the French language; it is the past participle of the verb ''parvenir'' (to reach, to arrive, to manage to do something).

Origin ...

, focused on improving his career and social standing using a combination of personal manipulation and conformity to popular styles. He follows a similar path in his private life: he chooses a loveless marriage to Dominique instead of marrying the woman he loveswho lacks Dominique's beauty and social connections. By middle age, Keating's career is in decline and he is unhappy with his path, but it is too late for him to change.

Rand did not use a specific architect as a model for Keating. Her inspiration for the character came from a neighbor she knew while working in Hollywood in the early 1930s. Rand asked this young woman to explain her goals in life. The woman's response was focused on social comparisons: The neighbor wanted her material possessions and social standing to equal or exceed those of other people. Rand created Keating as an archetype of this motivation, which she saw as the opposite of self-interest.

Dominique Francon

Gail Wynand

Gail Wynand is a wealthy newspaper mogul who rose from a destitute childhood in theghetto

A ghetto is a part of a city in which members of a minority group are concentrated, especially as a result of political, social, legal, religious, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished than other ...

es of New York (Hell's Kitchen

Hell's Kitchen, also known as Clinton, or Midtown West on real estate listings, is a neighborhood on the West Side of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York. It is considered to be bordered by 34th Street (or 41st Street) to the south, ...

) to control much of the city's print media. While Wynand shares many of the character qualities of Roark, his success is dependent upon his ability to pander to public opinion. Rand presents this as a tragic flaw

The term ''hamartia'' derives from the Greek , from ''hamartánein'', which means "to miss the mark" or "to err". It is most often associated with Greek tragedy, although it is also used in Christian theology. The term is often said to dep ...

that eventually leads to his downfall. In her journals Rand described Wynand as "the man who could have been" a heroic individualist, contrasting him to Roark, "the man who can be and is". Some elements of Wynand's character were inspired by real-life newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

,Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In including Hearst's yellow journalism

In journalism, yellow journalism and the yellow press are American newspapers that use eye-catching headlines and sensationalized exaggerations for increased sales. This term is chiefly used in American English, whereas in the United Kingdom, ...

and mixed success in attempts to gain political influence. Wynand ultimately fails in his attempts to wield power, losing his newspaper, his wife (Dominique), and his friendship with Roark. The character has been interpreted as a representation of the master morality

Master, master's or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

In education:

*Master (college), head of a college

*Master's degree, a postgraduate or sometimes undergraduate degree in the specified discipline

*Schoolmaster or master, presiding office ...

described by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

; his tragic nature illustrates Rand's rejection of Nietzsche's philosophy. In Rand's view, a person like Wynand, who seeks power over others, is as much a "second-hander" as a conformist such as Keating.

Ellsworth Toohey

ethical altruism

In ethical philosophy, altruism (also called the ethic of altruism, moralistic altruism, and ethical altruism) is an ethical doctrine that holds that the morality, moral value of an individual's actions depends solely on the impact of those action ...

and a rigorous egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hum ...

that treats all people and achievements as equally valuable. Rand used her memory of the democratic socialist British Labour Party chairman Harold Laski

Harold Joseph Laski (30 June 1893 – 24 March 1950) was an English political theorist and economist. He was active in politics and served as the chairman of the British Labour Party from 1945 to 1946 and was a professor at the London School of ...

to help her imagine what Toohey would do in a given situation. She attended a New York lecture by Laski as part of gathering material for the novel, following which she changed the physical appearance of the character to be similar to that of Laski. New York intellectuals Lewis Mumford

Lewis Mumford (October 19, 1895 – January 26, 1990) was an American historian, sociologist, philosopher of technology, and literary critic. Particularly noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, he had a broad career as a ...

and Clifton Fadiman

Clifton Paul "Kip" Fadiman (May 15, 1904 – June 20, 1999) was an American intellectual, author, editor, and radio and television personality. He began his work in radio, and switched to television later in his career.

Background

Born in Brook ...

also helped inspire the character.

History

Background and development

When Rand first arrived in New York as an immigrant from theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in 1926, she was greatly impressed by the Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

skyline's towering skyscrapers

A skyscraper is a tall continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Most modern sources define skyscrapers as being at least or in height, though there is no universally accepted definition, other than being very tall high-rise bui ...

, which she saw as symbols of freedom, and resolved that she would write about them. In 1927, Rand was working as a junior screenwriter for movie producer Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil Blount DeMille (; August 12, 1881January 21, 1959) was an American filmmaker and actor. Between 1914 and 1958, he made 70 features, both silent and sound films. He is acknowledged as a founding father of American cinema and the most co ...

when he asked her to write a script for what would become the 1928 film ''Skyscraper

A skyscraper is a tall continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Most modern sources define skyscrapers as being at least or in height, though there is no universally accepted definition, other than being very tall high-rise bui ...

''. The original story by Dudley Murphy

Dudley Bowles Murphy (July 10, 1897 – February 22, 1968) was an American film director.

Early life

Murphy was born on July 10, 1897, in Winchester, Massachusetts, to the artists Caroline Hutchinson (Bowles) Murphy (1868–1923) and Herma ...

was about two construction workers working on a skyscraper who are rivals for a woman's love. Rand rewrote it, transforming the rivals into architects. One of them, Howard Kane, was an idealist dedicated to erecting the skyscraper despite enormous obstacles. The film would have ended with Kane standing atop the completed skyscraper. DeMille rejected Rand's script, and the completed film followed Murphy's original idea. Rand's version contained elements she would use in ''The Fountainhead''.

In 1928, Rand made notes for a proposed, but never written, novel titled ''The Little Street''. Rand's notes for it contain elements that carried over into her work on ''The Fountainhead''. David Harriman, who edited the notes for the posthumously published ''Journals of Ayn Rand

A journal, from the Old French ''journal'' (meaning "daily"), may refer to:

*Bullet journal, a method of personal organization

*Diary, a record of personal secretive thoughts and as open book to personal therapy or used to feel connected to onesel ...

'' (1997), described the story's villain as a preliminary version of the character Ellsworth Toohey, and this villain's assassination by the protagonist as prefiguring the attempted assassination of Toohey.

Rand began ''The Fountainhead'' (originally titled ''Second-Hand Lives'') following the completion of her first novel, ''We the Living

''We the Living'' is the debut novel of the Russian American novelist Ayn Rand. It is a story of life in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, post-revolutionary Russia and was Rand's first statement against communism. Rand observes in t ...

'', in 1934. That earlier novel was based in part on people and events familiar to Rand; the new novel, on the other hand, focused on the less-familiar world of architecture. She therefore conducted extensive research that included reading many biographies and other books about architecture. She also worked as an unpaid typist in the office of architect Ely Jacques Kahn

Ely Jacques Kahn (June 1, 1884September 5, 1972) was an American commercial architect who designed numerous skyscrapers in New York City in the twentieth century. In addition to buildings intended for commercial use, Kahn's designs ranged throug ...

. Rand began her notes for the new novel in December 1935.

Rand wanted to write a novel that was less overtly political than ''We the Living'', to avoid being viewed as "a 'one-theme' author". As she developed the story, she began to see more political meaning in the novel's ideas about individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

. Rand also planned to introduce the novel's four sections with quotes from Friedrich Nietzsche, whose ideas had influenced her own intellectual development, but she eventually decided that Nietzsche's ideas were too different from hers. She edited the final manuscript to remove the quotes and other allusions to him.

Rand's work on ''The Fountainhead'' was repeatedly interrupted. In 1937, she took a break from it to write a novella called ''Anthem

An anthem is a musical composition of celebration, usually used as a symbol for a distinct group, particularly the national anthems of countries. Originally, and in music theory and religious contexts, it also refers more particularly to sho ...

''. One night in June 1938, she almost gave up on writing the book. Her husband Frank O'Connor

Frank O'Connor (born Michael Francis O'Donovan; 17 September 1903 – 10 March 1966) was an Irish author and translator. He wrote poetry (original and translations from Irish), dramatic works, memoirs, journalistic columns and features on as ...

encouraged her in an hours-long conversation, ultimately convincing her not to give up. She also completed a stage adaptation of ''We the Living'' that ran briefly in 1940. That same year, she became active in politics. She first worked as a volunteer in Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee for president. Willkie appeale ...

's presidential campaign and then attempted to form a group for conservative intellectuals. As her royalties from earlier projects ran out, she began doing freelance work as a script reader Script coverage is a filmmaking term for the analysis and grading of screenplays, often within the "script development" department of a production company. While coverage may remain entirely oral, it usually takes the form of a written report, guide ...

for movie studios. When Rand finally found a publisher, the novel was only one-third complete.

Publication history

Although she was a previously published novelist and had a successful Broadway play, Rand had difficulty finding a publisher for ''The Fountainhead''.Macmillan Publishing

Macmillan Publishers (occasionally known as the Macmillan Group; formally Macmillan Publishers Ltd in the United Kingdom and Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC in the United States) is a British publishing company traditionally considered to be on ...

, which had published ''We the Living'', rejected the book after Rand insisted they provide more publicity for her new novel than they had done for the first one. Rand's agent began submitting the book to other publishers; in 1938, Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

signed a contract to publish the book. When Rand was only a quarter done with the manuscript by October 1940, Knopf canceled her contract. Several other publishers rejected the book. When Rand's agent began to criticize the novel, Rand fired the agent and decided to handle submissions herself. Twelve publishers (including Macmillan and Knopf) rejected the book.

While Rand was working as a script reader for Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation, commonly known as Paramount Pictures or simply Paramount, is an American film production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the flagship namesake subsidiary of Paramount ...

, her boss put her in touch with the Bobbs-Merrill Company. A recently hired editor, Archibald Ogden, liked the book, but two internal reviewers gave conflicting opinions. One said it was a great book that would never sell; the other said it was trash but would sell well. Ogden's boss, Bobbs-Merrill president D.L. Chambers, decided to reject the book. Ogden responded by wiring

Electrical wiring is an electrical installation of cabling and associated devices such as switches, distribution boards, sockets, and light fittings in a structure.

Wiring is subject to safety standards for design and installation. Allow ...

to the head office, "If this is not the book for you, then I am not the editor for you." His strong stand won Rand the contract on December 10, 1941. She also got a $1,000 advance so she could work full-time to complete the novel by January 1, 1943.

Rand worked long hours through 1942 to complete the final two-thirds of her manuscript, which she delivered on December 31, 1942. Rand's working title for the book was ''Second-Hand Lives'', but Ogden pointed out that this emphasized the story's villains. Rand offered ''The Mainspring'' as an alternative, but this title had been recently used for another book. She then used a thesaurus

A thesaurus (: thesauri or thesauruses), sometimes called a synonym dictionary or dictionary of synonyms, is a reference work which arranges words by their meanings (or in simpler terms, a book where one can find different words with similar me ...

and found 'fountainhead' as a synonym. ''The Fountainhead'' was published on May 7, 1943, with 7,500 copies in the first printing. Initial sales were slow, but they began to rise in late 1943, driven primarily by word of mouth. The novel began appearing on bestseller lists in 1944. It reached number six on ''The New York Times'' bestseller list in August 1945, over two years after its initial publication. By 1956, the hardcover edition sold over 700,000 copies. The first paperback edition was published by the New American Library

The New American Library (also known as NAL) is an American publisher based in New York, founded in 1948. Its initial focus was affordable paperback reprints of classics and scholarly works as well as popular and pulp fiction, but it now publi ...

in 1952.

A 25th anniversary edition was issued by the New American Library in 1971, including a new introduction by Rand. The cover of the twenty-fifth anniversary edition featured a painting by Frank O'Connor titled ''Man Also Rises''. In 1993, a 50th anniversary edition from Bobbs-Merrill added an afterword by Rand's heir, Leonard Peikoff

Leonard Sylvan Peikoff (; born October 15, 1933) is a Canadian American philosopher. He is an Objectivist and was a close associate of Ayn Rand, who designated him heir to her estate. Peikoff is a former professor of philosophy and host of a na ...

. The novel has been translated into more than 30 languages.

Some passages were removed from the text prior to publication; the most substantial concerns the relationship of Howard Roark with actress Vesta Dunning, a character that was cut from the finished novel. The deleted passages were published posthumously in ''The Early Ayn Rand

''The Early Ayn Rand: A Selection from Her Unpublished Fiction'' is an anthology of unpublished early fiction written by the philosopher Ayn Rand, first published in 1984, two years after her death. The selections include short stories, plays, an ...

'' in 1984.

Themes

Individualism

Rand indicated that the primary theme of ''The Fountainhead'' was "individualism versus collectivism, not in politics but within a man's soul". Philosopher Douglas Den Uyl identified the individualism presented in the novel as being specifically of an American kind, portrayed in the context of that country's society and institutions. Apart from scenes such as Roark's courtroom defense of the American concept ofindividual rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

, she avoided direct discussion of political issues. As historian James Baker described it, "''The Fountainhead'' hardly mentions politics or economics, despite the fact that it was born in the 1930s. Nor does it deal with world affairs, although it was written during World War II. It is about one man against the system, and it does not permit other matters to intrude." Early drafts of the novel included more explicit political references, but Rand removed them from the finished text.

Architecture

Rand chose the profession of architecture as the background for her novel, although she knew nothing about the field beforehand.Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In As a field that combines art, technology, and business, it allowed her to illustrate her primary themes in multiple areas. Rand later wrote that architects provide "both art and a basic need of men's survival". In a speech to a chapter of the

Rand chose the profession of architecture as the background for her novel, although she knew nothing about the field beforehand.Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In As a field that combines art, technology, and business, it allowed her to illustrate her primary themes in multiple areas. Rand later wrote that architects provide "both art and a basic need of men's survival". In a speech to a chapter of the American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C. AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach progr ...

, Rand drew a connection between architecture and individualism, saying time periods that had improvements in architecture were also those that had more freedom for the individual.

Roark's modernist approach to architecture is contrasted with that of most of the other architects in the novel. In the opening chapter, the dean of his architecture school tells Roark that the best architecture must copy the past rather than innovate or improve. Roark repeatedly loses jobs with architectural firms and commissions from clients because he is unwilling to copy conventional architectural styles. In contrast, Keating's mimicry of convention brings him top honors in school and an immediate job offer. The same conflict between innovation and tradition is reflected in the career of Roark's mentor, Henry Cameron.

Philosophy

Den Uyl calls ''The Fountainhead'' a "philosophical novel", meaning that it addresses philosophical ideas and offers a specific philosophical viewpoint about those ideas. In the years following the publication of ''The Fountainhead'', Rand developed a philosophical system that she calledObjectivism

Objectivism is a philosophical system named and developed by Russian-American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. She described it as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive a ...

. ''The Fountainhead'' does not contain this explicit philosophy, and Rand did not write the novel primarily to convey philosophical ideas. Nonetheless, Rand included three excerpts from the novel in ''For the New Intellectual

''For the New Intellectual: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand'' is a 1961 work by the philosopher Ayn Rand. It is her first long non-fiction book. Much of the material consists of excerpts from Rand's novels, supplemented by a long title essay that focu ...

'', a 1961 collection of her writings that she described as an outline of Objectivism. Peikoff used many quotes and examples from ''The Fountainhead'' in his 1991 book on Rand's philosophy, '' Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand''.

Reception and legacy

Critical reception

''The Fountainhead'' polarized critics and received mixed reviews upon its release.Berliner, Michael S. "''The Fountainhead'' Reviews", in In ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', Lorine Pruette praised Rand as writing "brilliantly, beautifully and bitterly", stating that she had "written a hymn in praise of the individual" that would force readers to rethink basic ideas. Writing for the same newspaper, Orville Prescott

Orville Prescott (September 8, 1906, Cleveland, Ohio – April 28, 1996, New Canaan, Connecticut) was the main book reviewer for ''The New York Times'' for 24 years.

Biography

Born on September 8, 1906, in Cleveland, Ohio, Prescott graduated f ...

called the novel "disastrous" with a plot containing "coils and convolutions" and a "crude cast of characters". Benjamin DeCasseres, a columnist for the ''New York Journal-American

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 ...

'', described Roark as "one of the most inspiring characters in modern American literature". Rand sent DeCasseres a letter thanking him for explaining the book's themes about individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

when many other reviewers did not. There were other positive reviews, although Rand dismissed many of them as either not understanding her message or as being from unimportant publications. A number of negative reviews focused on the length of the novel, such as one that called it "a whale of a book" and another that said "anyone who is taken in by it deserves a stern lecture on paper-rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution (marketing), distribution of scarcity, scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resourc ...

". Other negative reviews called the characters unsympathetic and Rand's style "offensively pedestrian".

The character of Dominique Francon has provoked varied reactions from commentators. Philosopher Chris Matthew Sciabarra called her "one of the more bizarre characters in the novel". Literature scholar Mimi Reisel Gladstein

Mimi Reisel Gladstein (born 1936) is a professor of English and Theatre Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso. Her specialties include authors such as Ayn Rand and John Steinbeck, as well as women's studies, theatre arts and 18th-century Br ...

called her "an interesting case study in perverseness". Writer Tore Boeckmann described her as a character with conflicting beliefs and saw her actions as a logical representation of how those conflicts might play out.

In the years following its initial publication, ''The Fountainhead'' has received relatively little attention from literary critics. Assessing the novel's legacy, philosopher Douglas Den Uyl described ''The Fountainhead'' as relatively neglected compared to her later novel ''Atlas Shrugged

''Atlas Shrugged'' is a 1957 novel by Ayn Rand. It is her longest novel, the fourth and final one published during her lifetime, and the one she considered her ''magnum opus'' in the realm of fiction writing. She described the theme of ''Atlas ...

'' and said, "our problem is to find those topics that arise clearly with ''The Fountainhead'' and yet do not force us to read it simply through the eyes of ''Atlas Shrugged''." Among critics who have addressed it, some consider ''The Fountainhead'' to be Rand's best novel, although in some cases this assessment is tempered by an overall negative judgment of Rand's writings. Purely negative evaluations have also continued; a 2011 overview of American literature said "mainstream literary culture dismissed [] in the 1940s and continues to dismiss it".

Feminist criticisms

Feminism, Feminist critics have condemned Roark and Dominique's first sexual encounter, accusing Rand of endorsing rape. Feminist critics have attacked the scene as representative of anantifeminist

Antifeminism or anti-feminism is opposition to feminism. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, antifeminists opposed particular policy proposals for women's rights, such as women's suffrage, the right to vote, Female education, educat ...

viewpoint in Rand's works that makes women subservient to men. Susan Brownmiller

Susan Brownmiller (born Susan Warhaftig; February 15, 1935 – May 24, 2025) was an American journalist, author, and feminist activist, best known for her 1975 book '' Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape'', which was selected by The New ...

, in her 1975 work '' Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape'', denounced what she called "Rand's philosophy of rape", for portraying women as wanting "humiliation at the hands of a superior man". She called Rand "a traitor to her own sex". Susan Love Brown said the scene presents Rand's view of sex as sadomasochism

Sadism () and masochism (), known collectively as sadomasochism ( ) or S&M, is the derivation of pleasure from acts of respectively inflicting or receiving pain or humiliation. The term is named after the Marquis de Sade, a French author known ...

involving "feminine subordination and passivity". Barbara Grizzuti Harrison

Barbara Grizzuti Harrison (September 14, 1934 – April 24, 2002) was an American journalist, essayist and memoirist. She is best known for her autobiographical work, particularly her account of growing up as a Jehovah's Witness, and for her tra ...

suggested that women who enjoy such "masochistic fantasies" are "damaged" and have low self-esteem. While Mimi Reisel Gladstein found elements to admire in Rand's female protagonists, she said that readers who have "a raised consciousness about the nature of rape" would disapprove of Rand's "romanticized rapes".

Rand's posthumously published working notes for the novel indicate that when she started on the book in 1936, she conceived of Roark's character that "were it necessary, he could rape her and feel justified". She denied that what happened in the finished novel was actually rape, referring to it as "rape by engraved invitation". She said Dominique wanted and "all but invited" the act, citing, among other things, a passage where Dominique scratches a marble slab in her bedroom to invite Roark to repair it. A true rape, Rand said, would be "a dreadful crime". Defenders of the novel have agreed with this interpretation. In an essay specifically explaining this scene, Andrew Bernstein wrote that although much "confusion" exists about it, the descriptions in the novel provide "conclusive" evidence of Dominique's strong attraction to Roark and her desire to have sex with him. Individualist feminist Wendy McElroy

Wendy McElroy (born 1951) is a Canadian individualist feminist and voluntaryist writer. McElroy is the editor of the website ifeminists.net.

McElroy is the author of the book ''Rape Culture Hysteria'', in which she contends that rape cul ...

said that while Dominique is "thoroughly taken", there is nonetheless "clear indication" that Dominique both gave consent for and enjoyed the experience.McElroy, Wendy. "Looking Through a Paradigm Darkly". In Both Bernstein and McElroy saw the interpretations of feminists such as Brownmiller as based in a false understanding of sexuality.Bernstein, Andrew. "Understanding the 'Rape' Scene in ''The Fountainhead''". In

Effect on Rand's career

Although Rand had some mainstream success previously with her play ''

Although Rand had some mainstream success previously with her play ''Night of January 16th

''Night of January 16th'' (sometimes advertised as ''The Night of January 16th'') is a theatrical play by Russian-born American writer Ayn Rand, inspired by the death of Swedish industrialist Ivar Kreuger. The play is set in a courtroom dur ...

'' and had two previously published novels, ''The Fountainhead'' was a major breakthrough in her career. It brought her lasting fame and financial success. She sold the movie rights to ''The Fountainhead'' and returned to Hollywood to write the screenplay for the adaptation. In April 1944, she signed a multiyear contract with movie producer Hal Wallis

Harold B. Wallis (born Aaron Blum Wolowicz; October 19, 1898 – October 5, 1986) was an American film producer. He is best known for producing ''Casablanca'' (1942), ''The Adventures of Robin Hood'' (1938), and '' True Grit'' (1969), along wit ...

to write original screenplays and adaptations of other writers' works.

The success of the novel brought Rand new publishing opportunities. Bobbs-Merrill offered to publish a nonfiction book expanding on the ethical ideas presented in ''The Fountainhead''. Though this book was never completed, a portion of the material was used for an article in the January 1944 issue of ''Reader's Digest

''Reader's Digest'' is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year. Formerly based in Chappaqua, New York, it is now headquartered in midtown Manhattan. The magazine was founded in 1922 by DeWitt Wallace and his wi ...

''. Rand was also able to get an American publisher for ''Anthem'', which previously had been published in England, but not in the United States. When she was ready to submit ''Atlas Shrugged'' to publishers, over a dozen competed to acquire the new book.

''The Fountainhead'' also attracted a new group of fans who were attracted to its philosophical ideas. When she moved back to New York in 1951, she gathered a group of these admirers to whom she referred publicly as "the Class of '43" in reference to the year ''The Fountainhead'' was published. The group evolved into the core of the Objectivist movement

The Objectivist movement is a Social movement, movement of individuals who seek to study and advance Objectivism, the philosophy expounded by novelist-philosopher Ayn Rand. The movement began informally in the 1950s and consisted of students who ...

that promoted the philosophical ideas from Rand's writing.

Cultural influence

''The Fountainhead'' has continued to have strong sales throughout the last century into the current one. By 2023, it had sold over 10 million copies. It has been referred to in a variety of popular entertainments, including movies, television series, and other novels. The year 1943 also saw the publication of '' The God of the Machine'' byIsabel Paterson

Isabel Paterson (January 22, 1886 – January 10, 1961) was a Canadian-American libertarian writer and literary critic. Historian Jim Powell has called Paterson one of the three founding mothers of American libertarianism, along with Ros ...

and '' The Discovery of Freedom'' by Rose Wilder Lane

Rose Wilder Lane (December 5, 1886 – October 30, 1968) was an American writer and daughter of American writer Laura Ingalls Wilder. Along with two other female writers, Ayn Rand and Isabel Paterson, Lane is one of the more influential advoca ...

. Rand, Lane, and Paterson have been referred to as the founding mothers of the American libertarian movement with the publication of these works. For example, journalist John Chamberlain credited these works with converting him from socialism to what he called "an older American philosophy" of libertarian and conservative ideas. Literature professor Philip R. Yannella said the novel is "a central text of American conservative

''The American Conservative'' (''TAC'') is a bimonthly magazine published by the American Ideas Institute. The magazine was founded in 2002 by Pat Buchanan, Scott McConnell and Taki Theodoracopulos to advance an anti- neoconservative perspect ...

and libertarian political culture". In the United Kingdom, Conservative Party politician Sajid Javid

Sir Sajid Javid (; born 5 December 1969) is a British former politician who served as Secretary of State for Health and Social Care from June 2021 to July 2022, having previously served as Home Secretary from 2018 to 2019 and Chancellor of the ...

has spoken of the novel's influence on him and how he regularly rereads the courtroom scene from Roark's criminal trial.

The book has a particular appeal to young people, an appeal that led historian James Baker to describe it as "more important than its detractors think, although not as important as Rand fans imagine". Philosopher Allan Bloom

Allan David Bloom (September 14, 1930 – October 7, 1992) was an American philosopher, classicist, and academician. He studied under David Grene, Leo Strauss, Richard McKeon, and Alexandre Kojève. He subsequently taught at Cornell Un ...

said the novel is "hardly literature" but that when he asked his students which books mattered to them, someone always was influenced by ''The Fountainhead''. Journalist Nora Ephron

Nora Ephron ( ; May 19, 1941 – June 26, 2012) was an American journalist, writer, and filmmaker. She is best known for writing and directing romantic comedy films and received numerous accolades including a British Academy Film Award as ...

wrote that she had loved the novel when she was 18, but admitted that she "missed the point", which she suggested is largely subliminal sexual metaphor. Ephron wrote that she decided upon rereading that "it is better read when one is young enough to miss the point. Otherwise, one cannot help thinking it is a very silly book."

Multiple architects have cited ''The Fountainhead'' as an inspiration for their work. Architect Fred Stitt, founder of the San Francisco Institute of Architecture, dedicated a book to his "first architectural mentor, Howard Roark". According to architectural photographer Julius Shulman

Julius Shulman (October 10, 1910 – July 15, 2009) was an American architectural photographer best known for his photograph " Case Study House #22, Los Angeles, 1960. Pierre Koenig, Architect." The house is also known as the Stahl House. Shulm ...

, Rand's work "brought architecture into the public's focus for the first time". He said ''The Fountainhead'' was not only influential among 20th century architects, but moreover "was one, first, front and center in the life of every architect who was a modern architect". The novel also had a significant impact on the public perception of architecture. During his 2016 presidential campaign

This national electoral calendar for 2016 lists the national/ federal elections held in 2016 in all sovereign states and their dependent territories. By-elections are excluded, though national referendums are included.

January

*7 January: Kiri ...

, real estate developer Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

praised the novel, saying he identified with Roark. Roark Capital Group

Roark Capital Management, LLC, also known as Roark Capital Group or simply Roark Capital, is an American private equity firm with around $37 billion in assets under management. The firm is focused on leveraged buyout investments in middle-market ...

, a private equity firm, is named for the character Howard Roark.

Adaptations

Film

In 1949, Warner Bros. released a film based on the book, starringGary Cooper

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, silent screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, ...

as Howard Roark, Patricia Neal

Patricia Neal (born Patsy Louise Neal; January 20, 1926 – August 8, 2010) was an American actress of stage and screen. She is well known for, among other roles, playing World WarII widow Helen Benson in ''The Day the Earth Stood Still'' (195 ...

as Dominique Francon, Raymond Massey

Raymond Hart Massey (August 30, 1896 – July 29, 1983) was a Canadian actor known for his commanding stage-trained voice. For his lead role in '' Abe Lincoln in Illinois'' (1940), Massey was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor. He r ...

as Gail Wynand, and Kent Smith

Frank Kent SmithGordon, Dr. Roger L. (2018). Supporting Actors in Motion Pictures: Volume II'. Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Publishing. pp. 130, 131. . "Kent Smith: Frank Kent Smith was born on March 19, 1907, in New York City. ..He was marrie ...

as Peter Keating. Rand, who had previous experience as a screenwriter, was hired to adapt her own novel. The film was directed by King Vidor

King Wallis Vidor ( ; February 8, 1894 – November 1, 1982) was an American film director, film producer, and screenwriter whose 67-year film-making career successfully spanned the silent and sound eras. His works are distinguished by a vivid, ...

. It grossed $2.1 million, $400,000 less than its production budget. Critics panned the movie. Negative reviews appeared in publications ranging from newspapers such as ''The New York Times'' and the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'', to movie industry outlets such as ''Variety

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

'' and ''The Hollywood Reporter

''The Hollywood Reporter'' (''THR'') is an American digital and print magazine which focuses on the Cinema of the United States, Hollywood film industry, film, television, and entertainment industries. It was founded in 1930 as a daily trade pap ...

'', to magazines such as ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' and ''Good Housekeeping

''Good Housekeeping'' is an American lifestyle media brand that covers a wide range of topics from home decor and renovation, health, beauty and food, to entertainment, pets and gifts. The Good Housekeeping Institute which opened its "Experiment ...

''.

In letters written at the time, Rand's reaction to the film was positive. She said it was the most faithful adaptation of a novel ever made in Hollywood. and a "real triumph". Sales of the novel increased as a result of interest spurred by the film. She displayed a more negative attitude later, saying she disliked the entire movie and complaining about its editing, acting, and other elements. Rand said she would never sell rights to another novel to a film company that did not allow her to pick the director and screenwriter, as well as edit the film.

Various filmmakers have expressed interest in doing new adaptations of ''The Fountainhead'', although none of these potential films has begun production. In the 1970s, writer-director Michael Cimino

Michael Antonio Cimino ( , ; February 3, 1939 – July 2, 2016) was an American filmmaker. He achieved fame as the director of ''The Deer Hunter'' (1978), which won five Academy Awards, including Academy Award for Best Picture, Best Picture and ...

entered a deal to film his own script for United Artists

United Artists (UA) is an American film production and film distribution, distribution company owned by Amazon MGM Studios. In its original operating period, it was founded in February 1919 by Charlie Chaplin, D. W. Griffith, Mary Pickford an ...

starring Clint Eastwood

Clinton Eastwood Jr. (born May 31, 1930) is an American actor and film director. After achieving success in the Western (genre), Western TV series ''Rawhide (TV series), Rawhide'', Eastwood rose to international fame with his role as the "Ma ...

as Roark, but postponed the project in favor of abortive biographical film

A biographical film or biopic () is a film that dramatizes the life of an actual person or group of people. Such films show the life of a historical person and the central character's real name is used. They differ from Docudrama, docudrama films ...

s on Janis Joplin

Janis Lyn Joplin (January 19, 1943 – October 4, 1970) was an American singer and songwriter. One of the most iconic and successful Rock music, rock performers of her era, she was noted for her powerful mezzo-soprano vocals and her "electric" ...

and Frank Costello

Frank Costello (; born Francesco Castiglia ; January 26, 1891 – February 18, 1973) was an Italian-American crime boss of the Luciano crime family.

Born in Italy, he moved with his family to the United States as a child. As a youth he joined N ...

. The deal collapsed after the failure of Cimino's 1980 film '' Heaven's Gate'', which caused United Artists to refuse to finance any more of his films. Cimino continued to hope to film the script until his death in 2016.

In 1992, producer James Hill optioned the rights and selected Phil Joanou

Phil Joanou (born November 20, 1961) is an American director of film, music videos, and television programs. He is known for his collaborations with the rock band U2, for whom he directed music videos and their 1988 documentary film ''Rattle a ...

to direct. In the 2000s, Oliver Stone

William Oliver Stone (born ) is an American filmmaker. Stone is an acclaimed director, tackling subjects ranging from the Vietnam War and American politics to musical film, musical Biographical film, biopics and Crime film, crime dramas. He has ...

was interested in directing a new adaptation; Brad Pitt

William Bradley Pitt (born December 18, 1963) is an American actor and film producer. In a Brad Pitt filmography, film career spanning more than thirty years, Pitt has received list of awards and nominations received by Brad Pitt, numerous a ...

was reportedly under consideration to play Roark. In a March 2016 interview, director Zack Snyder

Zachary Edward Snyder (born March 1, 1966) is an American filmmaker. He made his feature film debut in 2004 with ''Dawn of the Dead (2004 film), Dawn of the Dead'', a remake of the 1978 horror film Dawn of the Dead (1978 film), of the same name ...

expressed interest in doing a new film adaptation of ''The Fountainhead'', an interest he repeated in 2018. Snyder said in 2019 that he was no longer pursuing the adaptation. In 2024, he said that he unsuccessfully pitched a television series adaptation to Netflix

Netflix is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service. The service primarily distributes original and acquired films and television shows from various genres, and it is available internationally in multiple lang ...

.

Play

The Dutch theater company

The Dutch theater company Toneelgroep Amsterdam

Toneelgroep Amsterdam is the largest repertory company in the Netherlands. Its home base is the Amsterdam Stadsschouwburg, a classical 19th century theatre building in the heart of Amsterdam. In 2018 Toneelgroep Amsterdam merged with Stadsscho ...

presented a Dutch-language adaptation for the stage at the Holland Festival

The Holland Festival () is the oldest and largest performing arts festival in the Netherlands. It takes place every June in Amsterdam. It comprises theatre, music, opera and modern dance. In recent years, multimedia, visual arts, film and architec ...

in June 2014. The company's artistic director Ivo van Hove

Ivo van Hove (born 28 October 1958) is a Belgian theatre director. He is known for his Off-Broadway avant-garde experimental theatre productions. For over twenty years, he served as the director of the Toneelgroep Amsterdam. On Broadway, he has d ...

wrote and directed the adaptation. Ramsey Nasr

Ramsey Nasr (born 28 January 1974) is a Dutch author and actor of mixed Palestinian and Dutch descent.

He was born in Rotterdam. He was ' (Poet of the Fatherland; an unofficial title for the Dutch poet laureate) between January 2009 and January ...

played Howard Roark, with Halina Reijn

Halina Reijn (; born 10 November 1975) is a Dutch actress, writer and film director.

Early life and education

Halina Reijn was born on 10 November 1975 in Amsterdam, Netherlands, to Fleur ten Kate and Frank Volkert Reijn (1931–1986). Reijn's ...

playing Dominique Francon. The four-hour production used video projections to show close-ups of the actors and Roark's drawings, as well as backgrounds of the New York skyline. After its debut the production went on tour, appearing in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Spain, in early July 2014, and at the Festival d'Avignon

The ''Festival d'Avignon'', or Avignon Festival (), is an annual arts festival held in the France, French city of Avignon every summer in July in the courtyard of the Palais des Papes as well as in other locations of the city. Founded in 1947 by ...

in France later that month. The play appeared at the Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe

The Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe (; "European Music Hall"; formerly the Théâtre de l'Odéon ; "Music Hall") is one of France's six national theatres. It is located at 2 Rue Corneille in the 6th arrondissement of Paris on the left bank of the ...

in Paris in November 2016, and at the LG Arts Center

GS Tower, also called GS Gangnam Tower (formerly LG Kangnam Tower), is a 38-story (173 meters) modern skyscraper located in the Gangnam District area of Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, cap ...

in Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

from March 31 to April 2, 2017. The play had its first American production at the Brooklyn Academy of Music

The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) is a multi-arts center in Brooklyn, New York City. It hosts progressive and avant-garde performances, with theater, dance, music, opera, film programming across multiple nearby venues.

BAM was chartered in 18 ...

's Next Wave Festival, where it ran from November 28 to December 2, 2017.

The European productions of the play received mostly positive reviews. The Festival d'Avignon production received positive from the French newspapers '' La Croix'', '' Les Échos'', and ''Le Monde

(; ) is a mass media in France, French daily afternoon list of newspapers in France, newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average print circulation, circulation of 480,000 copies per issue in 2022, including ...

'', as well as from the British newspaper ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', whose reviewer described it as "electrifying theatre". The French magazine ''Télérama

''Télérama'' is a weekly French language, French cultural and television magazine published in Paris, France. The name is a contraction of its earlier title: ''Télévision-Radio-Cinéma''. Fabienne Pascaud is currently managing editor. Ludovic ...

'' gave the Avignon production a negative review, calling the source material a minor work and complaining about the use of video screens on the set, while another French magazine, , complimented the staging and acting of the Odéon production.

American critics gave mostly negative reviews of the Next Wave Festival production. Helen Shaw's review for ''The Village Voice

''The Village Voice'' is an American news and culture publication based in Greenwich Village, New York City, known for being the country's first Alternative newspaper, alternative newsweekly. Founded in 1955 by Dan Wolf (publisher), Dan Wolf, ...

'' said the adaptation was unwatchable because it portrayed Rand's characters and views seriously without undercutting them The reviewer for the ''Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and also published digitally that focuses on business and economic Current affairs (news format), current affairs. Based in London, the paper is owned by a Jap ...

'' said the play was too long and that Hove had approached Rand's "noxious" book with too much reverence. In a mixed review for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', critic Ben Brantley

Benjamin D. Brantley (born October 26, 1954) is an American theater critic, journalist, editor, publisher, and writer. He served as the chief theater critic for ''The New York Times'' from 1996 to 2017, and as co-chief theater critic from 2017 t ...

complimented Hove for capturing Rand's "sheer pulp appeal", but described the material as "hokum with a whole lot of ponderous speeches". A review for ''The Huffington Post

''HuffPost'' (''The Huffington Post'' until 2017, itself often abbreviated as ''HPo'') is an American progressive news website, with localized and international editions. The site offers news, satire, blogs, and original content, and covers p ...

'' complimented van Hove's ability to portray Rand's message, but said the play was an hour too long.

Television

The novel was adapted inUrdu

Urdu (; , , ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in South Asia. It is the Languages of Pakistan, national language and ''lingua franca'' of Pakistan. In India, it is an Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of Indi ...

for the Pakistan Television Network

Pakistan Television Corporation (; reporting name: PTV); also known as ''Pakistan Television'', is the Pakistani state-owned broadcasting, broadcaster founded by the Government of Pakistan, operating under the Ministry of Information & Broadc ...

in 1980 under the title '' Teesra Kinara''. The serial starred Rahat Kazmi

Rahat Kazmi () is a Pakistani actor, screenwriter, TV news presenter anchorman, and an academician. He has worked in several TV serials for PTV such as in 1967 with ''Mayaar'', rose to prominence in 1974 with ''Qurbatain aur Faaslay'' (an ad ...

, who also wrote the adaptation. Kazmi's wife, Sahira Kazmi

Sahira Kazmi (born 8 April 1950) is a retired Pakistani actress, producer and director. She is best known for her role in the country's first-ever colour series ''Parchaiyan'' (1976) and for producing the cult-classic blockbuster series '' Dho ...

, played Dominique. In the US, the novel was parodied in an episode of the animated adventure series '' Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures'', as well as in season 20

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperate and polar ...

of the animated sitcom ''The Simpsons

''The Simpsons'' is an American animated sitcom created by Matt Groening and developed by Groening, James L. Brooks and Sam Simon for the Fox Broadcasting Company. It is a Satire (film and television), satirical depiction of American life ...

'' in the last part of the episode "Four Great Women and a Manicure

"Four Great Women and a Manicure" is the twentieth and penultimate episode of the twentieth season of the American animated television series ''The Simpsons''. First broadcast on the Fox network in the United States on May 10, 2009, it is the ...

".

Other adaptations

In 1944, '' Omnibook Magazine'' produced anabridged

An abridgement (or abridgment) is a condensing or reduction of a book or other creative work into a shorter form while maintaining the unity of the source. The abridgement can be true to the original work in terms of mood and tone, capturing th ...

edition of the novel that was sold to members of the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

. Rand was annoyed that Bobbs-Merrill allowed the edited version to be published without her approval of the text. King Features Syndicate

King Features Syndicate, Inc. is an American content distribution and animation studio, consumer product License, licensing and print syndication company owned by Hearst Communications that distributes about 150 comic strips, columnist, newspape ...

approached Rand the following year about creating a condensed, illustrated version of the novel for syndication in newspapers. Rand agreed, provided that she could oversee the editing and approve the proposed illustrations of her characters, which were provided by Frank Godwin

Francis Godwin (October 20, 1889 – August 5, 1959) was an American illustrator and comic strip artist, notable for his strip '' Connie'' and his book illustrations for '' Treasure Island'', '' Kidnapped'', '' Robinson Crusoe'', ''Robin Hood ...

. The 30-part series began on December 24, 1945, and ran in over 35 newspapers. Rand biographer Anne Heller complimented the adaptation, calling it "handsomely illustrated". To provide publicity for a translation of the novel into French, the Swiss publisher Jeheber allowed the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation

The Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (; ; ; ; SRG SSR) is the Swiss public broadcasting association, founded in 1931, the holding company of 24 radio and television channels. Headquartered in Bern, the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation is a non-pro ...

to air a radio play

Radio drama (or audio drama, audio play, radio play, radio theatre, or audio theatre) is a dramatised, purely acoustic performance. With no visual component, radio drama depends on dialogue, music and sound effects to help the listener imagine ...

adaptation in the late 1940s. Rand did not authorize the adaptation and learned about it through a letter from a Swiss fan in 1949.

See also

*Architecture of the United States

The architecture of the United States demonstrates a broad variety of architectural styles and built forms over the country's history of over two centuries of independence and former Spanish, French, Dutch and British rule.

Architecture in th ...

* Romantic realism

Romantic realism is art that combines elements of both romanticism and realism. The terms "romanticism" and "realism" have been used in varied ways, and are sometimes seen as opposed to one another.

In literature and art

The term has long standin ...

* Ely Jacques Kahn

Ely Jacques Kahn (June 1, 1884September 5, 1972) was an American commercial architect who designed numerous skyscrapers in New York City in the twentieth century. In addition to buildings intended for commercial use, Kahn's designs ranged throug ...

Notes

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Reprinted in * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Annual ''The Fountainhead'' essay contest

(Ayn Rand Institute)

CliffsNotes for ''The Fountainhead''

Panel discussion about "The Relevance of ''The Fountainhead'' in Today's World" on May 12, 2002

from

C-SPAN

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American Cable television in the United States, cable and Satellite television in the United States, satellite television network, created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a Non ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fountainhead, The

1943 American novels