The history of Argentina can be divided into four main parts: the pre-Columbian time or early history (up to the sixteenth century), the colonial period (1536–1809), the period of nation-building (1810–1880), and the history of modern Argentina (from around 1880).

Prehistory in the present territory of

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, t ...

began with the first human settlements on the southern tip of

Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and ...

around 13,000 years ago.

Written history began with the arrival of Spanish chroniclers in the expedition of

Juan Díaz de Solís

Juan Díaz de Solís ( – 20 January 1516) was a 16th-century navigator and explorer. He is also said to be the first European to land on what is now modern day Uruguay.

Biography

His origins are disputed. One document records him as a Portuguese ...

in 1516 to the

Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and f ...

, which marks the beginning of Spanish occupation of this region.

In 1776 the

Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

established the

Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata

The Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata ( es, Virreinato del Río de la Plata or es, Virreinato de las Provincias del Río de la Plata) meaning "River of the Silver", also called " Viceroyalty of the River Plate" in some scholarly writings, i ...

, an umbrella of territories from which, with the

Revolution of May 1810, began a process of gradual formation of several independent states, including one called the

United Provinces of the Río de la Plata

The United Provinces of the Río de la Plata ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata), earlier known as the United Provinces of South America ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas de Sudamérica), was a name adopted in 1816 by the Cong ...

. With the

declaration of independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of ...

on 9 July 1816, and the military defeat of the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

in 1824, a federal state was formed in 1853–1861, known today as the

Argentine Republic

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

.

Pre-Columbian era

The area now known as Argentina was relatively sparsely populated until the period of European colonization. The earliest traces of human life are dated from the

Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone to ...

period, and there are further signs in the

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymo ...

and

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

. However, large areas of the interior and Piedmont were apparently depopulated during an extensive dry period between 4000 and 2000 B.C.

The Uruguayan archaeologist Raúl Campá Soler divided the

indigenous peoples in Argentina

Argentina has 35 indigenous groups (often referred to as Argentine Amerindians or Native Argentines) according to the Complementary Survey of the Indigenous Peoples of 2004, the Argentine government's first attempt in nearly 100 years to recogni ...

into three main groups: basic hunters and food gatherers, without the development of

pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and po ...

; advanced gatherers and hunters; and basic farmers with pottery. The first group could be found in the

Pampas

The Pampas (from the qu, pampa, meaning "plain") are fertile South American low grasslands that cover more than and include the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, and Córdoba; all of Uruguay; and Bra ...

and

Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and ...

, and the second one included the

Charrúa

The Charrúa were an indigenous people or Indigenous Nation of the Southern Cone in present-day Uruguay and the adjacent areas in Argentina ( Entre Ríos) and Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul). They were a semi-nomadic people who sustained themsel ...

and

Minuane

Minuane were one of the native nations of Uruguay, Argentina (specially in the province of Entre Rios) and Brazil (specially in the state of Rio Grande do Sul). Their territory was along the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers. In one source, they are ...

and the

Guaraní Guarani, Guaraní or Guarany may refer to

Ethnography

* Guaraní people, an indigenous people from South America's interior (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia)

* Guaraní language, or Paraguayan Guarani, an official language of Paraguay

* ...

.

In the late 15th century, the Native tribes of the

Quebrada de Humahuaca

The Quebrada de Humahuaca is a narrow mountain valley located in the province of Jujuy in northwest Argentina, north of Buenos Aires (). It is about long, oriented north–south, bordered by the Altiplano in the west and north, by the Sub-Andea ...

were conquered by the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

, under

Topa Inca Yupanqui

Topa Inca Yupanqui or Túpac Inca Yupanqui ( qu, 'Tupaq Inka Yupanki'), translated as "noble Inca accountant," (c. 1441–c. 1493) was the tenth Sapa Inca (1471–93) of the Inca Empire, fifth of the Hanan dynasty. His father was Pachacuti, and h ...

, to secure the supply of metals such as silver, zinc, and copper. The Incan domination of the area lasted for about half a century and ended with the arrival of the Spanish in 1536.

Agriculture was practised in Pre-Hispanic Argentina as far south as southern

Mendoza Province

Mendoza, officially Province of Mendoza, is a province of Argentina, in the western central part of the country in the Cuyo region. It borders San Juan to the north, La Pampa and Neuquén to the south, San Luis to the east, and the republic ...

.

Agriculture was at times practised beyond this limit in nearby areas of Patagonia but populations reverted at times to non-agricultural lifestyles.

[ By the time of the Spanish arrival to the area (1550s) there is no record of agriculture being practised in northern Patagonia.][ The extensive ]Patagonian grasslands

The Patagonian grasslands (NT0804) is an ecoregion in the south of Chile, Argentina and the Falkland Islands. The grasslands are home to diverse fauna, including several rare or endemic species of birds. There are few protected areas. The grasslan ...

and an associated abundance of guanaco

The guanaco (; ''Lama guanicoe'') is a camelid native to South America, closely related to the llama. Guanacos are one of two wild South American camelids, the other being the vicuña, which lives at higher elevations.

Etymology

The guanaco ...

game may have contributed for the indigenous populations to favour a hunter-gathered lifestyle.[

]

Spanish colonial era

Europeans first arrived in the region with the 1502 Portuguese voyage of Gonçalo Coelho

Gonçalo Coelho (fl. 1501–04) was a Portuguese explorer who belonged to a prominent family in northern Portugal. He commanded two expeditions (1501–02 and 1503–04) which explored much of the coast of Brazil.

Biography

In 1501 Coelho was sen ...

and Amerigo Vespucci. Around 1512, João de Lisboa

João de Lisboa (c.1470 – 1525) was a Portuguese explorer. He is known to have sailed together with Tristão da Cunha, and to have explored Río de La Plata and possibly the San Matias Gulf, around 1511-12.

The Brazilian historian Francisco ...

and Estevão de Fróis discovered the Rio de La Plata in present-day Argentina, exploring its estuary, contacting the Charrúa people, and bringing the first news of the "people of the mountains", the Inca empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

, obtained from the local natives. They also traveled as far south as the Gulf of San Matias

A gulf is a large inlet from the ocean into the landmass, typically with a narrower opening than a bay, but that is not observable in all geographic areas so named. The term gulf was traditionally used for large highly-indented navigable bodies ...

at 42ºS, on the northern shores of Patagonia.

/ref> The Spanish, led by Juan Díaz de Solís

Juan Díaz de Solís ( – 20 January 1516) was a 16th-century navigator and explorer. He is also said to be the first European to land on what is now modern day Uruguay.

Biography

His origins are disputed. One document records him as a Portuguese ...

, visited the territory which is now Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, t ...

in 1516. In 1536 Pedro de Mendoza

Pedro de Mendoza () (c. 1499 – June 23, 1537) was a Spanish '' conquistador'', soldier and explorer, and the first ''adelantado'' of New Andalusia.

Setting sail

Pedro de Mendoza was born in Guadix, Grenada, part of a large noble family tha ...

established a small settlement at the modern location of Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the Capital city, capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata ...

, which was abandoned in 1541.[Mitre, pp. 8–9]

A second one was established in 1580 by Juan de Garay

Juan de Garay (1528–1583) was a Spanish conquistador.

Garay's birthplace is disputed. Some say it was in the city of Junta de Villalba de Losa in Castile, while others argue he was born in the area of Orduña (Basque Country). There's ...

, and Córdoba Córdoba most commonly refers to:

* Córdoba, Spain, a major city in southern Spain and formerly the imperial capital of Islamic Spain

* Córdoba, Argentina, 2nd largest city in the country and capital of Córdoba Province

Córdoba or Cordoba may ...

in 1573 by Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera

Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera (Sevilla, Spain, 1528 – Lima, 17 August 1574) was a Spanish conquistador, early colonial governor over much of what today is northwestern Argentina, and founder of the city of Córdoba.

Life and times

Cabrera was bo ...

. Those regions were part of the Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed fro ...

, whose capital was Lima, and settlers arrived from that city. Unlike the other regions of South America, the colonization of the Río de la Plata estuary was not influenced by any gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

, since it lacked any precious metal

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value.

Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lu ...

s to mine.Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and f ...

estuary

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environm ...

could not be used because all shipments were meant to be made through the port of Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists of the whole Call ...

near Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of t ...

, a condition that led to contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

becoming the normal means of commerce in cities such as Asunción

Asunción (, , , Guarani: Paraguay) is the capital and the largest city of Paraguay.

The city stands on the eastern bank of the Paraguay River, almost at the confluence of this river with the Pilcomayo River. The Paraguay River and the Bay o ...

, Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the Capital city, capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata ...

, and Montevideo

Montevideo () is the capital and largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . Montevideo is situated on the southern ...

.

The Spanish raised the status of this region by establishing the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata

The Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata ( es, Virreinato del Río de la Plata or es, Virreinato de las Provincias del Río de la Plata) meaning "River of the Silver", also called " Viceroyalty of the River Plate" in some scholarly writings, i ...

in 1776. This viceroyalty consisted of today's Argentina, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, and Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

, as well as much of present-day Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

. Buenos Aires, now holding the customs of the new political subdivision, became a flourishing port, as the revenues from the Potosí

Potosí, known as Villa Imperial de Potosí in the colonial period, is the capital city and a municipality of the Department of Potosí in Bolivia. It is one of the highest cities in the world at a nominal . For centuries, it was the location o ...

, the increasing maritime activity in terms of goods rather than precious metal

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value.

Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lu ...

s, the production of cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

for the export

An export in international trade is a good produced in one country that is sold into another country or a service provided in one country for a national or resident of another country. The seller of such goods or the service provider is an ...

of leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and ho ...

and other products, and other political reasons, made it gradually become one of the most important commercial centers of the region.

The viceroyalty was, however, short-lived due to lack of internal cohesion among its many regions and lack of Spanish support. Ships from Spain became scarce again after the Spanish defeat at the battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval battle, naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–De ...

, that gave the British maritime supremacy. The British tried to invade

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing c ...

Buenos Aires and Montevideo in 1806 and 1807, but were defeated both times by Santiago de Liniers

Santiago Antonio María de Liniers y Bremond, 1st Count of Buenos Aires, KOM, OM (July 25, 1753 – August 26, 1810) was a French officer in the Spanish military service, and a viceroy of the Spanish colonies of the Viceroyalty of the River Pl ...

. Those victories, achieved without help from mainland Spain, boosted the confidence of the city.

The beginning of the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spai ...

in Spain and the capture of the Spanish king Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

created great concern all around the viceroyalty. It was thought that, without a King, people in America should rule themselves. This idea led to multiple attempts to remove the local authorities at Chuquisaca, La Paz

La Paz (), officially known as Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Spanish pronunciation: ), is the seat of government of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. With an estimated 816,044 residents as of 2020, La Paz is the third-most populous city in Bo ...

, Montevideo and Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the Capital city, capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata ...

, all of which were short-lived. A new successful attempt, the May Revolution

The May Revolution ( es, Revolución de Mayo) was a week-long series of events that took place from May 18 to 25, 1810, in Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. This Spanish colony included roughly the terr ...

of 1810, took place when it was reported that all of Spain, with the exception of Cádiz and León, had been conquered.

War of Independence

The May Revolution ousted the viceroy. Other forms of government, such as a

The May Revolution ousted the viceroy. Other forms of government, such as a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies di ...

or a Regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

were briefly considered.

The viceroyalty was also renamed, and it nominally became the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata

The United Provinces of the Río de la Plata ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata), earlier known as the United Provinces of South America ( es, link=no, Provincias Unidas de Sudamérica), was a name adopted in 1816 by the Cong ...

. However, the status of the different territories that had belonged to the viceroyalty changed many times during the course of the war, as some regions would remain loyal to their previous governors and others were captured or recaptured; later these would split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, entertain ...

into several countries.

The first military campaigns against the royalists were waged by Manuel Belgrano

Manuel José Joaquín del Corazón de Jesús Belgrano y González (3 June 1770 – 20 June 1820), usually referred to as Manuel Belgrano (), was an Argentine public servant, economist, lawyer, politician, journalist, and military leader. He t ...

and Juan José Castelli

Juan José Castelli (19 July 176412 October 1812) was an Argentine lawyer who was one of the leaders of the May Revolution, which led to the Argentine War of Independence. He led an ill-fated military campaign in Upper Peru.

Juan José Castel ...

. The Primera Junta

The Primera Junta ( en, First Junta) or ''Junta Provisional Gubernativa de las Provincias del Río de la Plata'' (''Provisional Governing Junta of the Provinces of the Río de la Plata''), is the most common name given to the first government of ...

, after expanding to become the Junta Grande

Junta Grande (), or Junta Provisional Gubernativa de Buenos Aires, is the most common name for the executive government of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (modern-day Argentina), that followed the incorporation of provincial represe ...

, was replaced by the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many v ...

. A Second Triumvirate

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created for Mark Antony, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November 43 BC with ...

would replace it years later, calling for the Assembly of year XIII

The Assembly of Year XIII ( es, Asamblea del Año XIII) was a meeting called by the Second Triumvirate governing the young republic of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (modern-day Argentina, Uruguay, part of Bolivia) on October 1812 ...

that was meant to declare independence and write a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

. However, it did not do either, and replaced the triumvirates with a single head of state office, the Supreme Director.

By this time José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (25 February 177817 August 1850), known simply as José de San Martín () or '' the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru'', was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and cent ...

arrived in Buenos Aires with other generals of the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spai ...

. They gave new strength to the Revolutionary war, which was marked by the defeat of Belgrano and Castelli and the royalist resistance at the Banda Oriental. Alvear took Montevideo, and San Martín started a military campaign that would span an important part of the Spanish territories in America. He created the Army of the Andes

The Army of the Andes ( es, Ejército de los Andes) was a military force created by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (Argentina) and mustered by general José de San Martín in his campaign to free Chile from the Spanish Empire. In 181 ...

in Mendoza and, with the help of Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme (; August 20, 1778 – October 24, 1842) was a Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence. He was a wealthy landowner of Basque-Spanish and Irish ancestry. Alth ...

and other Chileans, he made the Crossing of the Andes

The Crossing of the Andes ( es, Cruce de los Andes) was one of the most important feats in the Argentine and Chilean wars of independence, in which a combined army of Argentine soldiers and Chilean exiles invaded Chile crossing the Andes ...

and liberated Chile. With the Chilean navy at his disposal, he moved to Peru, liberating that country as well. San Martín met Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and ...

at Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

, and retired from action.

A new assembly, the Congress of Tucumán

The Congress of Tucumán was the representative assembly, initially meeting in San Miguel de Tucumán, that declared the independence of the United Provinces of South America (modern-day Argentina, Uruguay, part of Bolivia) on July 9, 1816, f ...

, was called while San Martín was preparing the crossing of the Andes. It finally declared independence from Spain or any other foreign power. Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

declared itself independent in 1825, and Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

was created in 1828 as a result of the Cisplatine War

The Cisplatine War (), also known as the Argentine-Brazilian War () or, in Argentine and Uruguayan historiography, as the Brazil War (''Guerra del Brasil''), the War against the Empire of Brazil (''Guerra contra el Imperio del Brasil'') or t ...

.

The French-Argentine Hippolyte Bouchard

Hippolyte or Hipólito Bouchard (15 January 1780 – 4 January 1837) was a French-born Argentine sailor and corsair who fought for Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

During his first campaign as an Argentine corsair he attacked the Spanish colonies of ...

then brought his fleet to wage war against Spain overseas and attacked Spanish California, Spanish Chile, Spanish Peru and Spanish Philippines. He secured the allegiance of escaped Filipinos in San Blas who defected from the Spanish to join the Argentine navy, due to common Argentine and Philippine grievances against Spanish colonization. At a later date, the Argentine Sun of May

The Sun of May () is a national emblem of Argentina and Uruguay, and appears on the flags of both countries.

__TOC__

History

According to Diego Abad de Santillán, the Sun of May represents Inti, the Incan god of the sun.

The specification ...

was adopted as a symbol by the Filipinos in the Philippine Revolution against Spain. Bouchard also secured the diplomatic recognition of Argentina from King Kamehameha I

Kamehameha I (; Kalani Paiea Wohi o Kaleikini Kealiikui Kamehameha o Iolani i Kaiwikapu kaui Ka Liholiho Kūnuiākea; – May 8 or 14, 1819), also known as Kamehameha the Great, was the conqueror and first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Th ...

of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Historian Pacho O'Donnell affirms that Hawaii was the first state that recognized Argentina's independence.

The United Kingdom officially recognized Argentine independence in 1825, with the signing of a ''Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation'' on February 2; the British chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassado ...

in Buenos Aires, Woodbine Parish

Sir Woodbine Parish KCH (14 September 1796, London – 16 August 1882, St. Leonards, Sussex) was a British diplomat, traveller and scientist.

The son of Woodbine Parish, of Bawburgh Old Hall, Norfolk, a major in the Light Horse Volunteers, ...

, signed on behalf of his country. Spanish recognition of Argentine independence was not to come for several decades.

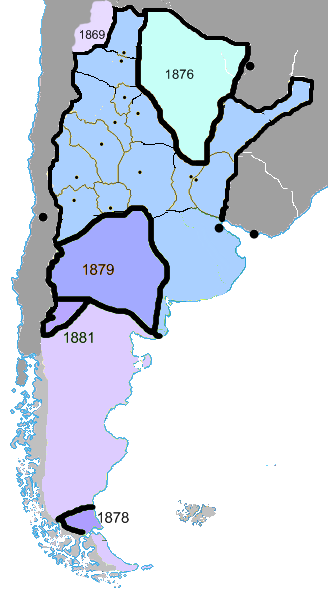

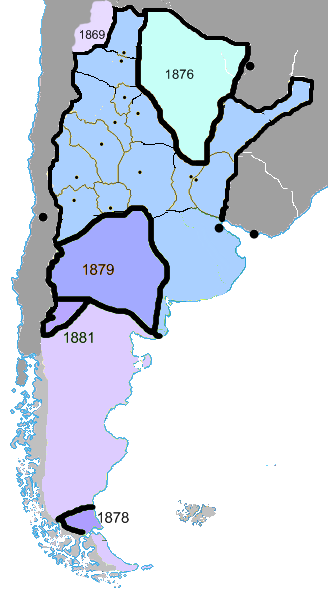

Historical map

The map below is based on a wide range of antique maps for the periods shown and is intended to give a broad idea of the changes in the State of Argentina in the nineteenth century. The periods are broad and plus or minus about a decade around each date. The hatched areas are disputed or subject to change during the period, the text in this article will explain these changes. There are minor changes of territory that are not shown on the map.

Argentine Civil Wars

The defeat of the Spanish was followed by a long civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

between unitarians

Unitarian or Unitarianism may refer to:

Christian and Christian-derived theologies

A Unitarian is a follower of, or a member of an organisation that follows, any of several theologies referred to as Unitarianism:

* Unitarianism (1565–present) ...

and federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of d ...

, about the organization of the country and the role of Buenos Aires in it. Unitarians thought that Buenos Aires should lead the less-developed provinces, as the head of a strong centralized government

A centralized government (also united government) is one in which both executive and legislative power is concentrated centrally at the higher level as opposed to it being more distributed at various lower level governments. In a national conte ...

. Federalists thought instead that the country should be a federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

of autonomous provinces, like the United States. During this period, the government would kidnap protestors, and torture them for information.

During this period, the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata lacked a head of state, since the unitarian defeat at the Battle of Cepeda had ended the authority of the Supreme Directors and the 1819 Constitution. There was a new attempt in 1826 to write a constitution, leading to the designation of Bernardino Rivadavia

Bernardino de la Trinidad González Rivadavia (May 20, 1780 – September 2, 1845) was the first President of Argentina, then called the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, from February 8, 1826 to June 27, 1827.

He was educated at t ...

as President of Argentina

The president of Argentina ( es, Presidente de Argentina), officially known as the president of the Argentine Nation ( es, Presidente de la Nación Argentina), is both head of state and head of government of Argentina. Under the national cons ...

, but it was rejected by the provinces. Rivadavia resigned due to the poor management at the Cisplatine War

The Cisplatine War (), also known as the Argentine-Brazilian War () or, in Argentine and Uruguayan historiography, as the Brazil War (''Guerra del Brasil''), the War against the Empire of Brazil (''Guerra contra el Imperio del Brasil'') or t ...

, and the 1826 constitution was repealed.

During this time, the Governors of Buenos Aires Province

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

received the power to manage the international relations of the confederation, including war and debt payment. The dominant figure of this period was the federalist Juan Manuel de Rosas

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws", was an Argentine politician and army officer who ruled Buenos Aires Province and briefly the Argentine Confederation. Althoug ...

, who is portrayed from different angles by the diverse historiographic flows in Argentina: liberal history usually considers him a dictator, while revisionists support him on the grounds of his defense of national sovereignty.

He ruled the province of Buenos Aires from 1829 to 1852, facing military threats from secession attempts, neighboring countries, and even European nations. Although Rosas was a Federalist, he kept the customs receipts of Buenos Aires under the exclusive control of the city, whereas the other provinces expected to have a part of the revenue. Rosas considered this a fair measure because only Buenos Aires was paying the external debt

A country's gross external debt (or foreign debt) is the liabilities that are owed to nonresidents by residents. The debtors can be governments, corporations or citizens. External debt may be denominated in domestic or foreign currency. It incl ...

generated by the Baring Brothers

Barings Bank was a British merchant bank based in London, and one of England's oldest merchant banks after Berenberg Bank, Barings' close collaborator and German representative. It was founded in 1762 by Francis Baring, a British-born member of ...

loan to Rivadavia, the war of independence and the war against Brazil. He developed a paramilitary force of his own, the Popular Restorer Society, commonly known as "''Mazorca''" ("Corncob").

Rosas' reluctance to call for a new assembly to write a constitution led General Justo José de Urquiza

Justo José de Urquiza y García (; October 18, 1801 – April 11, 1870) was an Argentine general and politician who served as president of the Argentine Confederation from 1854 to 1860.

Life

Justo José de Urquiza y García was bo ...

from Entre Ríos to turn against him. Urquiza defeated Rosas during the battle of Caseros

The Battle of Caseros ( es, Batalla de Caseros) was fought near the town of El Palomar, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, on 3 February 1852, between the Army of Buenos Aires commanded by Juan Manuel de Rosas and the Grand Army (''Ejército ...

and called for such an assembly. The Argentine Constitution of 1853

The Argentine Constitution of 1853 is the current constitution of Argentina. It was approved in 1853 by all of the provincial governments except Buenos Aires Province, which remained separate from the Argentine Confederation until 1859. Aft ...

is, with amendments, still in force to this day. The Constitution was not immediately accepted by Buenos Aires, which seceded from the Confederation; it rejoined a few years later. In 1862 Bartolomé Mitre

Bartolomé Mitre Martínez (26 June 1821 – 19 January 1906) was an Argentine statesman, soldier and author. He was President of Argentina from 1862 to 1868 and the first president of unified Argentina.

Mitre is known as the most versatile ...

became the first president of the unified country.

Liberal governments (1862–1880)

The presidency of

The presidency of Bartolomé Mitre

Bartolomé Mitre Martínez (26 June 1821 – 19 January 1906) was an Argentine statesman, soldier and author. He was President of Argentina from 1862 to 1868 and the first president of unified Argentina.

Mitre is known as the most versatile ...

saw an economic improvement in Argentina, with agricultural modernization, foreign investment, new railroads and ports and a wave of immigration from Europe. Mitre also stabilized the political system by commanding federal interventions that defeated the personal armies of caudillos Chacho Peñaloza

Chacho is a male nickname in Spanish-speaking countries, often a diminutive form of " muchacho". It may refer to:

People

* Chacho Peñaloza (1796–1863), Argentine military officer and politician

* Chacho (footballer) Eduardo González Valiño ...

and Juan Sáa

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of ''John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanish, t ...

. Argentina joined Uruguay and Brazil against Paraguay in the War of the Triple Alliance

The Paraguayan War, also known as the War of the Triple Alliance, was a South American war that lasted from 1864 to 1870. It was fought between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance of Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay. It was the deadlies ...

, which ended during Sarmiento's rule with the defeat of Paraguay and the annexation of part of its territory by Argentina.

Despite victory in the war, Mitre's popularity declined severely because a broad section of the Argentine population was opposed to the war due to the alliance with Brazil (Argentina's historic rival) that took place during the war, and the betrayal of Paraguay (which had been until then one of the country's most important economic allies). One of the major hallmarks of Mitre's presidency was the "Law of Compromise", in which Buenos Aires joined the Argentine Republic and allowed the government to use the City of Buenos Aires as the center of government, but without federalizing the city and by reserving the right of the province of Buenos Aires to secede from the nation if conflict arose.

In 1868 Mitre was succeeded by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (; born Domingo Faustino Fidel Valentín Sarmiento y Albarracín; 15 February 1811 – 11 September 1888) was an Argentine activist, intellectual, writer, statesman and the second President of Argentina. His writing sp ...

, who promoted public education, culture, telegraphs

Telegraphs were an alternative rock band based in Brighton, England.

Biography

Formed in 2005, Telegraphs was made up of members Darcy Harrison (vocals), Hattie Williams (bass/vocals), Sam Bacon (drums), Darren LeWarne (guitar) and Aung Yay ( ...

; as well as the modernization of the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and the Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It include ...

. Sarmiento managed to defeat the last known caudillos and also dealt with the fallout of the Triple Alliance War, which included a decrease in national production due to the death of thousands of soldiers and an outbreak of diseases, such as cholera and yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

, brought by returning soldiers.

In 1874 Nicolás Avellaneda

Nicolás Remigio Aurelio Avellaneda Silva (3 October 1837 – 24 November 1885) was an Argentine politician and journalist, and President of Argentina from 1874 to 1880. Avellaneda's main projects while in office were banking and education ...

became president and ran into trouble when he had to deal with the economic depression left by the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an depression (economics), economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in United Kingdom, Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two ...

. Most of these economic issues were solved when new land was opened for development after the expansion of national territory through the Conquest of the Desert

The Conquest of the Desert ( es, Conquista del desierto) was an Argentine military campaign directed mainly by General Julio Argentino Roca in the 1870s with the intention of establishing dominance over the Patagonian Desert, inhabited primari ...

, led by his war minister Julio Argentino Roca

Alejo Julio Argentino Roca Paz (July 17, 1843 – October 19, 1914) was an army general and statesman who served as President of Argentina from 1880 to 1886 and from 1898 to 1904. Roca is the most important representative of the Generation ...

. This military campaign took most of the territories under the control of natives, and reduced their population.

In 1880 a trade conflict caused turmoil in Buenos Aires, which led governor Carlos Tejedor to declare secession from the republic. Avellaneda denied them this right, breaking the Law of Compromise, and proceeded to send army troops led by Roca to take over the province. Tejedor's secession efforts were defeated and Buenos Aires joined the republic definitively, federalizing the city of Buenos Aires and handing it over to the government as the nation's capital city.

Conservative Republic (1880–1916)

After his surge in popularity due to his successful desert campaign, Julio Roca was elected president in 1880 as the candidate for the

After his surge in popularity due to his successful desert campaign, Julio Roca was elected president in 1880 as the candidate for the National Autonomist Party

The National Autonomist Party ( es, Partido Autonomista Nacional; PAN) was the ruling political party of Argentina from 1874 to 1916.

In 1880, Julio Argentino Roca assumed the presidency under the motto "peace and administration".

History

The ...

(Partido Autonomista Nacional – PAN), a party that would remain in power until 1916. During his presidency, Roca created a net of political alliances and installed several measures that helped him retain almost absolute control of the Argentine political scene throughout the 1880s. This keen ability with political strategy earned him his nickname of "''The Fox''".

The country's economy benefited from a change from extensive farming

Extensive farming or extensive agriculture (as opposed to intensive farming) is an Agriculture production system that uses small inputs of labour, fertilizers, and capital, relative to the land area being farmed.

Systems

Extensive farming i ...

to industrial agriculture

Industrial agriculture is a form of modern farming that refers to the industrialized production of crops and animals and animal products like eggs or milk. The methods of industrial agriculture include innovation in agricultural machinery and farm ...

and a huge European immigration, but there wasn't yet a strong move towards industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econ ...

. At that time, Argentina received some of the highest levels of foreign investment in Latin America. In the midst of this economic expansion, the Law 1420 of Common Education of 1884 guaranteed universal, free, non-religious education to all children. This and other government policies were strongly opposed by the Roman Catholic Church in Argentina, causing the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

to break off diplomatic relations with the country for several years and setting the stage for decades of continued Church–state strain.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Argentina temporarily resolved its border disputes with Chile with the Puna de Atacama dispute

The Puna de Atacama dispute, sometimes referred to as Puna de Atacama Lawsuit (Spanish: ''Litigio de la Puna de Atacama''), was a border dispute involving Argentina, Chile and Bolivia in the 19th century over the arid high plateau of Puna de Atac ...

of 1899, the Boundary Treaty of 1881 between Chile and Argentina and the 1902 General Treaty of Arbitration

Nineteen or 19 may refer to:

* 19 (number), the natural number following 18 and preceding 20

* one of the years 19 BC, AD 19, 1919, 2019

Films

* ''19'' (film), a 2001 Japanese film

* ''Nineteen'' (film), a 1987 science fiction film

Music ...

. Roca's government and those that followed were aligned with the Argentine oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, ...

, especially the great land owners.

In 1888,

In 1888, Miguel Juárez Celman

-->

Miguel is a given name and surname, the Portuguese and Spanish form of the Hebrew name Michael. It may refer to:

Places

* Pedro Miguel, a parish in the municipality of Horta and the island of Faial in the Azores Islands

* São Miguel (disa ...

became president after Roca was constitutionally disqualified from re-election; Celman attempted to reduce Roca's control over the political scene, which earned him his predecessor's opposition. Roca led a great opposition movement against Celman, which coupled with the devastating effects that the Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing str ...

had on the Argentine economy, allowed the Civic opposition party to start a coup d'état which would be later known as the Revolution of the Park

The Revolution of the Park (''Revolución del Parque''), also known as the Revolution of '90, was an uprising against the national government of Argentina that took place on July 26, 1890, and started with the takeover of the Buenos Aires Artille ...

. The Revolution was led by the three main leaders of the Civic Union, Leandro Alem

Leandro Nicéforo Alem (born Leandro Alén; 11 March 1841 – 1 July 1896) was an Argentine politician, founder and leader of the Radical Civic Union. He was the uncle and political teacher of Hipólito Yrigoyen. He was also an active Freemas ...

, former president Bartolomé Mitre

Bartolomé Mitre Martínez (26 June 1821 – 19 January 1906) was an Argentine statesman, soldier and author. He was President of Argentina from 1862 to 1868 and the first president of unified Argentina.

Mitre is known as the most versatile ...

and moderate socialist Juan B. Justo

Juan Bautista Justo (June 28, 1865, in Buenos Aires – January 8, 1928, in Buenos Aires) was an Argentine physician, journalist, politician, and writer. After finishing medical school he joined the Civic Union of the Youth, later participating ...

. Though it failed in its main goals, the revolution forced Juárez Celman's resignation and marked the decline of the Generation of '80

The Generation of '80 ( es, Generación del '80) was the governing elite in Argentina from 1880 to 1916. Members of the oligarchy of the provinces and the country's capital, they first joined the League of Governors (''Liga de Gobernadores''), a ...

.

In 1891, Roca proposed that the Civic Union elect someone to be vice-president to his own presidency the next time elections came around. One group led by Mitre decided to take the deal, while another more intransigent group led by Alem was opposed. This eventually led to the split of the Civic Union into the National Civic Union (Argentina)

The National Civic Union (in Spanish ''Unión Cívica Nacional'') was a liberal political party in Argentina formed in 1891 as the result of a split in the Civic Union, and dissolved in 1916. It based largely on the personality of its leader, Ba ...

, led by Mitre, and the Radical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union ( es, Unión Cívica Radical, UCR) is a centrist and social-liberal political party in Argentina. It has been ideologically heterogeneous, ranging from social liberalism to social democracy. The UCR is a member of the ...

, led by Alem. After this division occurred, Roca withdrew his offer, having completed his plan to divide the Civic Union and decrease their power. Alem would eventually commit suicide in 1896; control of the Radical Civic Union went to his nephew and protégé, Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

.

After Celman's downfall, his vice-president Carlos Pellegrini

Carlos Enrique José Pellegrini Bevans (October 11, 1846 – July 17, 1906) was Vice President of Argentina and became President of Argentina from August 6, 1890 to October 12, 1892, upon Miguel Ángel Juárez Celman's resignation (see Re ...

took over and proceeded to resolve the economic crisis which afflicted the country, earning him the moniker of "''The Storm Sailor''". Fearing another wave of opposition from Roca like the one imposed on Celman, Pellegrini remained moderate in his presidency ending his predecessor's efforts to distance "''The Fox''" from political control. The following governments up until 1898 took similar measures and sided with Roca to avoid being politically chastised.

In 1898, Roca became president again in a politically unstable situation, with a large number of social conflicts that included massive strikes and anarchist subversion attempts. Roca handled most of these conflicts by having the police or the army crack down on protestors, rebels and suspected rebels. After the end of his second presidency, Roca fell ill and his role in political affairs began to decrease gradually until his death in late 1914.

In 1904, Alfredo Palacios

Alfredo Lorenzo Palacios (August 10, 1880 – April 20, 1965) was an Argentine socialist politician.

Palacios was born in Buenos Aires, and studied law at University of Buenos Aires, after graduation he became a lawyer and taught at the unive ...

, a member of Juan B. Justo

Juan Bautista Justo (June 28, 1865, in Buenos Aires – January 8, 1928, in Buenos Aires) was an Argentine physician, journalist, politician, and writer. After finishing medical school he joined the Civic Union of the Youth, later participating ...

's Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of t ...

(founded in 1896), became the first Socialist deputy in Argentina, as a representative for the working-class neighborhood of La Boca

La Boca (; "the Mouth", probably of the Matanza River) is a neighborhood (''barrio'') of Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina. It retains a strong Italian flavour, many of its early settlers having originated in the city of Genoa.

Geography

...

in Buenos Aires. He helped create many laws, including the Ley Palacios against sexual exploitation, and others regulating child and woman labor, working hours and Sunday rest.

Unión Cívica Radical's 1893 and 1905 revolts, led by Hipólito Yrigoyen, inflicted fear among the oligarchy of an increased social instability and a possible revolution. Being a progressive member of the PAN, Roque Sáenz Peña

Roque José Antonio del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Sáenz Peña Lahitte (19 March 1851 – 9 August 1914) was an Argentine politician and lawyer who served as President of Argentina from 12 October 1910 to his death in office on 9 August 1914. ...

recognized the need to satisfy the demand by public to maintain the existing regime. After being elected as president in 1910, he passed the Sáenz Peña Law

The Sáenz Peña Law () was Law 8871 of Argentina, sanctioned by the National Congress on 10 February 1912, which established the universal, secret and compulsory male suffrage though the creation of an electoral list (''Padrón Electoral''). It ...

in 1912 which made the political vote mandatory, secret and universal among males aged eighteen or more. His intention was not to allow the transition of power to Unión Cívica Radical but to increase public support for the PAN by enabling the universal electoral suffrage. However, the consequence was the opposite of what he intended to accomplish: The following election chose Hipólito Yrigoyen as the president in 1916, and it ended the hegemony of the PAN.

Radical governments (1916–30)

Conservative forces dominated Argentine politics until 1916, when the Radicals, led by

Conservative forces dominated Argentine politics until 1916, when the Radicals, led by Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

, won control of the government through the first national elections under universal male suffrage. 745,000 citizens were allowed to vote, of a total population of 7.5 million (immigrants, who represented much of the population, were not allowed to vote); of these, 400,000 abstained.

Yrigoyen, however, only obtained 45% of the votes, which did not allow him a majority in Parliament, where the conservatives remained the leading force. Thus, of 80 draft laws proposed by the executive, only 26 were voted through by the conservative majority.[Felipe Pigna, 2006, p. 42] A moderate agricultural reform proposal was rejected by Parliament, as was an income tax on interest, and the creation of a Bank of the Republic (which was to have the missions of the current Central Bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a centra ...

).Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

. Neutrality enabled Argentina to export goods to Europe, in particular to Great Britain, as well as to issue credit to the belligerent powers. Germany sank two Argentine civilian ships, ''Monte Protegido'' on 4 April 1917, and the ''Toro'', but the diplomatic incident ended only with the expulsion of the German ambassador, Karl von Luxburg

Karl von Luxburg (10 May 1872 in Würzburg – 2 April 1956 in Ramos Mejía, Argentina) was German chargé d'affaires at Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1917, during World War I.

Incident

In the summer of 1917, Luxburg sent secret dispatches to Berl ...

. Yrigoyen organized a Conference of Neutral Powers in Buenos Aires, to oppose the United States' attempt to bring American states in the European war, and also supported Sandino's resistance in Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean Sea, Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to ...

.

Despite conservative opposition, the Radical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union ( es, Unión Cívica Radical, UCR) is a centrist and social-liberal political party in Argentina. It has been ideologically heterogeneous, ranging from social liberalism to social democracy. The UCR is a member of the ...

(UCR), with their emphasis on fair elections and democratic institutions, opened their doors to Argentina's expanding middle class as well as to social groups previously excluded from power. Yrigoyen's policy was to "fix" the system, by enacting necessary reforms which would enable the agroindustrial export model to preserve itself. It alternated moderate social reforms with repression of the social movements. In 1918, a student movement started at the University of Córdoba, which eventually led to the University Reform University reform is a type of education reform applied to higher education.

Examples include:

*Argentine university reform of 1918

*Chilean university reform

*Reform of French universities

** Law on Higher Education and Research (2007)

**Liberties ...

, which quickly spread to the rest of Latin America. In May '68

Beginning in May 1968, a period of civil unrest occurred throughout France, lasting some seven weeks and punctuated by demonstrations, general strikes, as well as the occupation of universities and factories. At the height of events, which h ...

, French students recalled the Córdoba movement.

The Tragic Week of January 1919, during which the Argentine Regional Workers' Federation

The Argentine Regional Workers' Federation (Spanish: ''Federación Obrera Regional Argentina''; abbreviated FORA), founded in , was Argentina's first national labor confederation. It split into two wings in 1915, the larger of which merged into ...

(FORA, founded in 1901) had called for a general strike after a police shooting, ended with 700 killed and 4,000 injured. General Luis Dellepiane

General Luis J. Dellepiane (26 April 1865 – 14 August 1941), born in Buenos Aires, was a civil engineer, militarist and politician of Argentina.

With the title of Lieutenant General he participated in the politics linked to the Radical ...

marched on Buenos Aires to re-establish civil order. Despite being called on by some to initiate a coup against Yrigoyen, he remained loyal to the President, on the sole condition that the latter would allow him a free hand in the repression of the demonstrations. Social movements thereafter continued in the ''Forestal Forestal is a solvent used in chromatography, composed of acetic acid, water, and hydrochloric acid in a 30:10:3 ratio by volume. It is useful for isolating anthocyanin

Anthocyanins (), also called anthocyans, are water-soluble vacuolar pigme ...

'' British company, and in Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and ...

, where Hector Varela headed the military repression, assisted by the Argentine Patriotic League

The Argentine Patriotic League ( es, Liga Patriótica Argentina) was a '' Nacionalista'' paramilitary group, officially created in Buenos Aires on January 16, 1919, during the Tragic week events. Presided over by Manuel Carlés, a professor at ...

, killing 1,500.

On the other hand, Yrigoyen's administration enacted the Labor Code establishing the right to strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Labor (economics), work. A strike usually takes place in response to grievance (labour), employee grievance ...

in 1921, implemented minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. B ...

laws and collective contracts. It also initiated the creation of the ''Dirección General de Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales

YPF S.A. (, formerly ; English: "Fiscal Oilfields") is a vertically integrated, majority state-owned Argentine energy company, engaged in oil and gas exploration and production, and the transportation, refining, and marketing of gas and pet ...

'' (YPF), the state oil company, in June 1922. Radicalism rejected class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

and advocated social conciliation.

In September 1922, Yrigoyen's administration refused to follow the ''cordon sanitaire

''Cordon sanitaire'' () is French for "sanitary cordon". It may refer to:

* Cordon sanitaire (medicine), a cordon that quarantines an area during an infectious disease outbreak

* Cordon sanitaire (politics), refusal to cooperate with certain polit ...

'' policy enacted against the Soviet Union, and, basing its policy on the assistance given to Austria after the war, decided to send to the USSR 5 million pesos in assistance.

The same year, Yrigoyen was replaced by his rival inside the UCR, Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear

Máximo Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear Pacheco (4 October 1868 – 23 March 1942), was an Argentine lawyer and politician, who served as president of Argentina between from 1922 to 1928.

His period of government coincided precisely with the en ...

, an aristocrat, who defeated Norberto Piñero

Norberto Piñero (1858–1938) was a prominent Argentine lawyer, writer and conservative politician.

Life and times

Norberto Piñero was born to a landed family in the Province of Buenos Aires, in 1858. He enrolled at the University of Bueno ...

's '' Concentración Nacional'' (conservatives) with 458,457 votes to 200,080. Alvear brought to his cabinet personalities belonging to the traditional ruling classes, such as José Nicolás Matienzo

José Nicolás Matienzo (October 4, 1860January 3, 1936) was a prominent Argentine lawyer, writer, academic, and policy maker.

Life and times

José Nicolás Matienzo was born in San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina, in 1860. He enrolled at the U ...

at the Interior Ministry, Ángel Gallardo Ángel Gallardo may refer to:

* Ángel Gallardo (civil engineer) (1867–1934), Argentine civil engineer, natural scientist, and politician

* Ángel Gallardo (golfer) (born 1943), Spanish golfer

* Ángel Ballesteros Gallardo (born 1940), Spanish poe ...

in Foreign Relations, Agustín P. Justo

Agustín is a Spanish given name and sometimes a surname. It is related to Augustín. People with the name include:

Given name

* Agustín (footballer), Spanish footballer

* Agustín Calleri (born 1976), Argentine tennis player

* Agustín Cár ...

at the War Ministry, Manuel Domecq García

Manuel may refer to:

People

* Manuel (name)

* Manuel (Fawlty Towers), a fictional character from the sitcom ''Fawlty Towers''

* Charlie Manuel, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies

* Manuel I Komnenos, emperor of the Byzantine Empire

* Ma ...

at the Marine and Rafael Herrera Vegas

Rafael may refer to:

* Rafael (given name) or Raphael, a name of Hebrew origin

* Rafael, California

* Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, Israeli manufacturer of weapons and military technology

* Hurricane Rafael, a 2012 hurricane

Fiction

* ''R ...

at the Haciendas. Alvear's supporters founded the ''Unión Cívica Radical Antipersonalista Unión may refer to:

Places

* Unión, Paraguay

* Unión Municipality, Falcón, Venezuela

* Unión, Montevideo, Uruguay

* Unión Cantinil, Huehuetenango, Guatemala

* Unión, San Luis, Argentina

* Unión Department, Córdoba Province, Argentina

* Uni ...

'', opposed to Yrigoyen's party.

During the early 1920s, the rise of the anarchist movement, fueled by the arrival of recent émigrés and deportees from Europe, spawned a new generation of left-wing activism in Argentina. The new left, mostly anarchists and anarcho-communists

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains re ...

, rejected the incremental progressivism of the old Radical and Socialist elements in Argentina in favor of immediate action. The extremists, such as Severino Di Giovanni

Severino Di Giovanni (17 March 1901 – 1 February 1931) was an Italian anarchist who immigrated to Argentina, where he became the best-known anarchist figure in that country for his campaign of violence in support of Sacco and Vanzetti and Mili ...

, openly espoused violence and 'propaganda by the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

'. A wave of bombings and shootouts with police culminated in an attempt to assassinate U.S. President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, holding o ...

on his visit to Argentina in 1928 and a nearly successful attempt to assassinate Yrigoyen in 1929 after he was re-elected to the presidency.

In 1921, the counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revolut ...

''Logia General San Martín

The term ''logia'' ( el, λόγια), plural of ''logion'' ( el, λόγιον), is used variously in ancient writings and modern scholarship in reference to communications of divine origin. In pagan contexts, the principal meaning was "oracles", ...

'' was founded, and diffused nationalist ideas in the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distin ...

until its dissolution in 1926. Three years later, the ''Liga Republicana

Liga or LIGA may refer to:

People

* Līga (name), a Latvian female given name

* Luciano Ligabue, more commonly known as Ligabue or ''Liga'', Italian rock singer-songwriter

Sports

* Liga ACB, men's professional basketball league in Spain

* Liga ...

'' (Republican League) was founded by Roberto de Laferrère Roberto de Laferrère (10 January 1900, Buenos Aires - 31 January 1963, Buenos Aires) was an Argentinean writer and political activist. He was one of the leading figures in the nationalist movement active amongst a group of leading intellectuals in ...

, on the model of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

's Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Natio ...

in Italy. The Argentine Right found its major influences in the 19th-century Spanish writer Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo

Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo (; 3 November 1856 – 19 May 1912) was a Spanish scholar, historian and literary critic. Even though his main interest was the history of ideas, and Hispanic philology in general, he also cultivated poetry, transl ...

and in the French royalist Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (; ; 20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was a French author, politician, poet, and critic. He was an organizer and principal philosopher of ''Action Française'', a political movement that is monarchist, anti-par ...

. Also in 1922, the poet Leopoldo Lugones

Leopoldo Antonio Lugones Argüello (13 June 1874 – 18 February 1938) was an Argentine poet, essayist, novelist, playwright, historian, professor, translator, biographer, philologist, theologian, diplomat, politician and journalist. His poetic ...

, who had turned towards fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

, made a famous speech in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of t ...

, known as "the time of the sword", in the presence of the War Minister and future dictator Agustín P. Justo, which called for a military coup and the establishment of a military dictatorship.

In 1928, Yrigoyen was re-elected as president and began a series of reforms to increase workers' rights. This intensified the conservative opposition against Yrigoyen, which grew even stronger after Argentina was devastated by the beginning of the Great Depression after the Wall Street Crash

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

. On September 6, 1930, a military coup led by the pro-fascist general José Félix Uriburu

Lieutenant General José Félix Benito Uriburu y Uriburu (20 July 186829 April 1932) was the President of the Provisional Government of Argentina, ousting the successor to President Hipólito Yrigoyen by means of a military coup and declaring ...

overthrew Yrigoyen's government and began a period in Argentine history known as the Infamous Decade

The Infamous Decade () was a period in Argentinian history that began with the 1930 coup d'état against President Hipólito Yrigoyen. This decade was marked on one hand by significant rural exodus, with many small rural landowners ruined by ...

.

During the Great Depression, exports of frozen beef, especially to Great Britain, provided much needed foreign currency, but trade fell off sharply.

Infamous Decade (1930–43)

In 1929, Argentina was wealthy by world standards, but the prosperity ended after 1929 with the worldwide Great Depression. In 1930, a military coup, supported by the

In 1929, Argentina was wealthy by world standards, but the prosperity ended after 1929 with the worldwide Great Depression. In 1930, a military coup, supported by the Argentine Patriotic League

The Argentine Patriotic League ( es, Liga Patriótica Argentina) was a '' Nacionalista'' paramilitary group, officially created in Buenos Aires on January 16, 1919, during the Tragic week events. Presided over by Manuel Carlés, a professor at ...

, forced Hipólito Yrigoyen from power, and replaced him with José Félix Uriburu

Lieutenant General José Félix Benito Uriburu y Uriburu (20 July 186829 April 1932) was the President of the Provisional Government of Argentina, ousting the successor to President Hipólito Yrigoyen by means of a military coup and declaring ...

. Support for the coup was bolstered by the sagging Argentine economy, as well as a string of bomb attacks and shootings involving radical anarchists, which alienated moderate elements of Argentine society and angered the conservative right, which had long been agitating for decisive action by the military forces.

The military coup initiated during the period known as the "Infamous Decade

The Infamous Decade () was a period in Argentinian history that began with the 1930 coup d'état against President Hipólito Yrigoyen. This decade was marked on one hand by significant rural exodus, with many small rural landowners ruined by ...

", characterized by electoral fraud, persecution of the political opposition

In politics, the opposition comprises one or more political parties or other organized groups that are opposed, primarily ideologically, to the government (or, in American English, the administration), party or group in political control of ...

(mainly against the UCR) and pervasive government corruption, against the background of the global depression.

During his brief tenure as president, Uriburu cracked down heavily on anarchists and other far-left groups, resulting in 2,000 illegal executions of members of anarchist and communist groups. The most famous (and perhaps most symbolic of anarchism's decay in Argentina at the time) was the execution of Severino Di Giovanni

Severino Di Giovanni (17 March 1901 – 1 February 1931) was an Italian anarchist who immigrated to Argentina, where he became the best-known anarchist figure in that country for his campaign of violence in support of Sacco and Vanzetti and Mili ...

, who was captured in late January 1931 and executed on the first of February of the same year.

After becoming president through the coup, Uriburu attempted to create a constitutional reform that would include corporatism