In the

early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, from about 1400 to 1775, about 100,000 people were prosecuted for

witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

in

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and

British America

British America collectively refers to various British colonization of the Americas, colonies of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and its predecessors states in the Americas prior to the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War in 1 ...

. Between 40,000 and 60,000

were executed, almost all in Europe. The

witch-hunt

A witch hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or Incantation, incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the ...

s were particularly severe in parts of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. Prosecutions for witchcraft reached a high point from 1560 to 1630,

during the

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

and the

European wars of religion

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in Europe during the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries. Fought after the Protestant Reformation began in 1517, the wars disrupted the religious and political order in the Catholic Chu ...

. Among the lower classes, accusations of witchcraft were usually made by neighbors, and women and men made formal accusations of witchcraft. Magical healers or '

cunning folk

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, White magic, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Th ...

' were sometimes prosecuted for witchcraft, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused.

Roughly 80% of those convicted were women, most of them over the age of 40.

In some regions, convicted witches were

burnt at the stake, the traditional punishment for religious

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

.

Medieval background

Christian doctrine

Throughout the

medieval era

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and t ...

, mainstream Christian doctrine had denied the belief in the existence of witches and witchcraft, condemning it as a

pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic (supernatural), magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly app ...

. Some have argued that the work of the

Dominican Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; ŌĆō 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

in the 13th century helped lay the groundwork for a shift in Christian doctrine, by which certain Christian theologians eventually began to accept the possibility of collaboration with devil(s), resulting in a person obtaining certain real supernatural powers. Christians as a whole were not of the belief that magic in its entirety is demonic, for members of the clergy practiced crafts such as necromancy, the practice of communicating with the dead. However, witchcraft was still assumed as inherently demonic, so backlash to witches was inevitable due to the collective negative image.

A branch of the inquisition in southern France

In 1233, a papal bull by

Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 ŌĆō 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the P ...

established a new branch of the inquisition in

Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

, France, to be led by the

Dominicans

Dominicans () also known as Quisqueyans () are an ethnic group, ethno-nationality, national people, a people of shared ancestry and culture, who have ancestral roots in the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican ethnic group was born out of a fusio ...

. It was intended to prosecute Christian groups considered heretical, such as the

Cathars

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a he ...

and the

Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

. The Dominicans eventually evolved into the most zealous prosecutors of persons accused of witchcraft in the years leading up to the Reformation.

Records were usually kept by the French inquisitors, but the majority of these records did not survive, and one historian who was working in 1880, Charles Molinier, refers to the surviving records as only scanty debris. Molinier notes that the inquisitors themselves describe their attempts to carefully safeguard their records, especially when they were moving from town to town. The inquisitors were widely hated and they would be ambushed on the road, but their records were more often the target than the inquisitors themselves

'plus d├®sireux encore de ravir les papiers que porte le juge que de le faire p├®rir lui-m├¬me''(''better to take the papers the judge carries than to make the judge himself perish''). The records seem to have often been targeted by the accused or their friends and family, wishing to thereby sabotage the proceedings or failing that, to spare their reputations and the reputations of their descendants. This would be all the more true for those who were accused of practicing witchcraft. Difficulty in understanding the larger witchcraft trials which were to come in later centuries is deciding how much can be extrapolated from what remains.

14th century

There was no concept of demonic witchcraft during the fourteenth century; only at a later time did a unified concept combine the ideas of noxious magic, a pact with the Devil and an assembly of witches for Satanic worship into one category of crime. Witch trials were infrequent compared to later centuries and a significant proportion of them were held in France. Until 1330 the trials were linked to prominent figures in the church or politics, as victims or as accused suspects, and more than half took place in France, where it was the usual way of explaining royal deaths in the

direct Capetian line. The papacy of

John XXII was another engine for witchcraft accusations. There were also a significant number of trials in England and Germany. The charges were generally mild. Diabolism, believed to involve nocturnal orgies and traditionally linked to accusations of heresy, was a very rare charge in the witch trials. After 1334 the political dimension of witchcraft accusations disappeared, while the charges remained mild. The large majority of trials until 1375 were in France and Germany. The number of witch trials rose after 1375, when many municipal courts adopted inquisitorial procedure and penalties for false accusations were abolished. Prominent centres of witch prosecutions were France, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. In Italy a new development occurred when accusations of diabolism gradually became more common and more important in prosecutions, although they were still less common than trials for sorcery. Records of witch trials from this century also lacked extensive descriptions of meetings of witches.

[Jeffrey Burton Russell, Witchcraft in the Middle Ages, 186]

In 1329, with the papacy in nearby Avignon, the inquisitor of Carcassonne sentenced a Carmelite friar called Peter Recordi to the dungeon for life. The sentence refers to ... ''multas et diversas daemonum conjurationes et invocationes'' ... and it frequently uses the same Latin synonym as a word for witchcraft, ''sortilegia''ŌĆöfound on the title page of

Nicolas R├®my'

work from 1595 where it is claimed that 900 persons were executed for ''sortilegii crimen''. He was accused of using love magic to seduce women and of invoking Satan and sacrificing a butterfly to him.

Lamothe-Langon

Earlier works on witchcraft often placed a large number of stereotypical witch trials in southern France in the early fourteenth century. This is the result of

├ētienne-L├®on de Lamothe-Langon

├ētienne-L├®on de Lamothe-Langon (1786-1864) was a prolific French author of many novels, apocryphal memoirs, and a controversial historical work.

Biography

├ētienne-L├®on de Lamothe-Langon, a descendant of an old family of Languedoc, was b ...

, who published ''Histoire de l'inquisition en France'' in 1829. He described a sudden outburst of mass witch trials ending in hundreds of executions, and the accused were portrayed as the stereotypical demonic witch. He purported to extensively quote in translation from inquisitorial records. His book proved influential.

Joseph Hansen included large excerpts from the book, though Lamothe-Langon's sources could not be found at the end of the nineteenth century. Through reuse by other writers, Lamothe-Langon's work established the view that witch hunts suddenly began in the late Middle Ages and implied a link with

Catharism

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a he ...

. Academics continued to rely on Lamothe-Langon as a source until

Norman Cohn

Norman Rufus Colin Cohn FBA (12 January 1915 ŌĆō 31 July 2007) was a British academic, historian and writer who spent 14 years as a professorial fellow and as Astor-Wolfson Professor at the University of Sussex.

Life

Cohn was born in London, ...

and

Richard Kieckhefer showed independently in the 1970s that the alleged records in ''Histoire de l'inquisition'' were highly dubious and possible forgeries. Kieckhefer notes that a 1855 publication of a summary inventory from inquisitorial records from Carcassonne did not match with Lamothe-Langon's work at all. Besides, the language and stereotypes in the supposed records were anachronistic. Lamothe-Langon also had a track record in forging several genealogies about his ancestry and his political motive was shown by his polemics against censorship. By the time that historians rejected his work, it was already firmly entrenched in the popular image of witchcraft.

15th century trials and the growth of the new heterodox view

Witch trials were still uncommon in the 15th century when the concept of diabolical witchcraft began to emerge. The study of four chronicles concerning events in

Valais

Valais ( , ; ), more formally, the Canton of Valais or Wallis, is one of the cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of thirteen districts and its capital and largest city is Sion, Switzer ...

, the

Bernese Alps

The Bernese Alps are a mountain range of the Alps located in western Switzerland. Although the name suggests that they are located in the Berner Oberland region of the canton of Bern, portions of the Bernese Alps are in the adjacent cantons of Va ...

and the nearby region of

Dauphin├®

The Dauphin├® ( , , ; or ; or ), formerly known in English as Dauphiny, is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Is├©re, Dr├┤me and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphin├® was ...

has supported the scholarly proposal that some ideas concerning witchcraft were taking hold in the region around western Switzerland during the 1430s, recasting the practice of witchcraft as an alliance between a person and the devil that would undermine and threaten the Christian foundation of society.

The

Perrissona Gappit case tried in Switzerland in 1465 is noted for the thoroughness of the surviving record.

The skeptical

Canon Episcopi

The title canon ''Episcopi'' (or ''capitulum Episcopi'') is conventionally given to a certain passage found in medieval canon law. The text possibly originates in an early 10th-century penitential, recorded by Regino of Pr├╝m; it was included in ...

retained many supporters, and still seems to have been supported by the theological faculty at the University of Paris in their decree from 1398. It was never officially repudiated by a majority of bishops within the papal lands, nor even by the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

, which immediately preceded the peak of the trials. But in 1428, the

Valais witch trials, lasting six to eight years, started in the French-speaking lower Valais and eventually spread to German-speaking regions. This time period also coincided with the

Council of Basel (1431ŌĆō1437) and some scholars have suggested a new anti-witchcraft doctrinal view may have spread among certain theologians and inquisitors in attendance at this council as the Valais trials were discussed. Not long after, a cluster of powerful opponents of the Canon Episcopi emerged: a Dominican inquisitor in Carcassonne named Jean Vinet, the Bishop of Avila Alfonso Tostado, and another Dominican Inquisitor named

Nicholas Jacquier. It is unclear whether the three men were aware of each other's work. The coevolution of their shared view centres around "a common challenge: disbelief in the reality of demonic activity in the world."

Nicholas Jacquier's lengthy and complex argument against the Canon Episcopi was written in Latin. It began as a tract in 1452 and was expanded into a fuller monograph in 1458. Many copies seem to have been made by hand (nine manuscript copies still exist), but it was not printed until 1561. Jacquier describes a number of trials he personally witnessed, including one of a man named

Guillaume Edelin, against whom the main charge seems to have been that he had preached a sermon in support of the Canon Episcopi claiming that witchcraft was merely an illusion. Edelin eventually recanted this view, most likely under torture.

1486: ''Malleus Maleficarum''

The most important and influential book which promoted the new heterodox view was the ''

Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic Church, Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinisation of names, Latini ...

'', published in 1487 by clergyman and German inquisitor Heinrich Kramer, accompanied by Jacobus Sprenger. ''

Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic Church, Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinisation of names, Latini ...

'' is split up into three different sections, each individual section addressing an aspect of witches and their culture. The following sections were magic, a witches origin, and appropriate punishment. The appropriate punishment section divides offenses into three different levels, ranging from slight, great, and very great. Slight could be something as simple as a small group meeting to practice witchcraft, while on the other hand, very great included respecting and admiring heretics. Kramer begins his work in opposition to the Canon Episcopi, but oddly, he does not cite Jacquier, and he may not have been aware of his work. Like most witch-phobic writers, Kramer had met strong resistance by those who opposed his heterodox view; this inspired him to write his work as both propaganda and a manual for like-minded zealots. The

Gutenberg printing press had only recently been invented along the Rhine River, and Kramer fully utilized it to shepherd his work into print and spread the ideas that had been developed by inquisitors and theologians in France into the Rhineland. The theological views espoused by Kramer were influential but remained contested. Nonetheless ''Malleus Maleficarum'' was printed 13 times between 1486 and 1520, and ŌĆö following a 50-year pause that coincided with the height of the Protestant reformations ŌĆö it was printed again another 16 times (1574ŌĆō1669) in the decades following the important

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

which had remained silent with regard to Kramer's theological views. It inspired many similar works, such as an influential work by

Jean Bodin

Jean Bodin (; ; ŌĆō 1596) was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. Bodin lived during the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and wrote against the background of reli ...

, and was cited as late as 1692 by

Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style ŌĆō August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a History of New England, New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the sixth President of Harvard University, President of Harvard College (la ...

, then president of Harvard College.

The increased demonization of witches blossomed in relation with the expansion and increased popularity of the ''Malleus Maleficarum''. Given the book was published nearly thirty times between the years 1487 and 1669 across Europe, it easily provided Europe's literate citizens with a more concrete, solidified depiction of a witch. Kramer creates an idea of a new medieval witch, that being an evil woman, which far outstretches to the modern day. Through the spread of Kramer's depiction of a witch through this book, the public outlook of witchcraft soon transformed from evil to demonic.

It is unknown if a degree of alarm at the extreme superstition and witch-phobia expressed by Kramer in the ''Malleus Maleficarum'' may have been one of the numerous factors that helped prepare the ground for the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

.

A difference between earlier accusations and modern day accusations is that in the 1500s, accusations were rooted in fears of malicious supernatural harm ŌĆō often attributed to familiar spirits. This led to formal witch trials and executions. Such accusations targeted individuals suspected of curses, causing ailments or crop failures, reflecting deep-seated anxieties about hidden malevolent forces within rural communities.

Malleus Maleficarum (1487) was accused. In the modern period, it was more aligned with evolving perspectives on magic and the supernatural, influenced by scientific progress and Enlightenment thinking.

Peak of the trials: 1560ŌĆō1630

The period of the European witch trials with the most active phase and which saw the largest number of fatalities seems to have occurred between 1560 and 1630.

[ Thurston 2001. p. 79.] The period between 1560 and 1670 saw more than 40,000 deaths.

Authors have debated whether witch trials were more intense in Catholic or Protestant regions; however, the intensity had not so much to do with Catholicism or Protestantism as both regions experienced a varied intensity of witchcraft persecutions. In Catholic Spain and Portugal for example, the numbers of witch trials were few because the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions preferred to focus on the crime of public

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

rather than the crime of witchcraft, whereas Protestant Scotland had a much larger number of witchcraft trials. In contrast, the witch trials in the Protestant Netherlands stopped earlier and they were among the least numerous in Europe, while the large-scale mass witch trials which took place in the autonomous territories of the Catholic

prince-bishop

A prince-bishop is a bishop who is also the civil ruler of some secular principality and sovereignty, as opposed to '' Prince of the Church'' itself, a title associated with cardinals. Since 1951, the sole extant prince-bishop has been the ...

s in Southern Germany were infamous in all of the

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

, and the contemporary writer Herman L├Čher described how they affected the population within them:

[Ankarloo, Bengt, Witchcraft and magic in Europe. Vol. 4, The period of the witch trials, Athlone, London, 2002]

The Roman Catholic subjects, farmers, winegrowers, and artisans in the episcopal lands are the most terrified people on earth, since the false witch trials affect the German episcopal lands incomparably more than France, Spain, Italy or Protestants.

The mass witch trials took place in Southern Catholic Germany in waves between the 1560s and the 1620s. Some trials went on to continue for years and would result in hundreds of executions of both sexes, all ages and classes. These included the

Trier witch trials (1581ŌĆō1593), the

Fulda witch trials (1603ŌĆō1606), the

Eichst├żtt witch trials (1613ŌĆō1630), the

W├╝rzburg witch trials (1626ŌĆō1631), and the

Bamberg witch trials (1626ŌĆō1631). The W├╝rzburg witch trials were among the largest and deadliest in history, and they highlighted the growing paranoia and the power of witchcraft accusations to manipulate political and religious conflicts. They were conducted from 1626 to 1631 under Prince-Bishop Philipp Adolf von Ehrenberg and led to the execution of approximately 900 individuals. Victims spanned all social classes, including nobles, councilmen, and even children as young as seven. The trials were characterized by the use of torture to extract confessions and the naming of alleged accomplices, which caused a cycle of accusations and executions. Another famous trial that happened during this time was that of Ursuala Kemp. KempŌĆÖs case showed what happens when a woman does not conform to societal expectations due to the accusations made by Thurlow and Letherdale.

In 1590 the

North Berwick witch trials

The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick on Halloween night. They ran for two years, and implicated over 70 peopl ...

occurred in Scotland and were of particular note as the king,

James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

, became involved himself. James had developed a fear that witches planned to kill him after

he suffered from storms while traveling to Denmark in order to claim his bride,

Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

, earlier that year. Returning to Scotland, the king heard of trials that were occurring in

North Berwick

North Berwick (; ) is a seaside resort, seaside town and former royal burgh in East Lothian, Scotland. It is situated on the south shore of the Firth of Forth, approximately east-northeast of Edinburgh. North Berwick became a fashionable holi ...

, and ordered the suspects to be brought to himŌĆöhe subsequently believed that a nobleman,

Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell

Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell (c. December 1562 ŌĆō November 1612), was Commendator of Kelso Abbey and Coldingham Priory, a Privy Counsellor and Lord High Admiral of Scotland. He was a notorious conspirator who led several uprisings aga ...

, was a witch, and after the latter fled in fear of his life he was outlawed as a traitor. The king subsequently set up royal commissions to hunt down witches in his realm, recommending torture in dealing with suspects, and in 1597 wrote a book about the menace witches posed to society entitled ''

Daemonologie

''Daemonologie''ŌĆöin full ''D├”monologie, In Forme of a Dialogue, Divided into three Books: By the High and Mightie Prince, James &c.''ŌĆöwas first published in 1597 by King James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England) as a philosophi ...

''.

The

Pendle witch trials of 1612 are some of the most prominent in English history, resulting in the hanging of ten of the eleven who were tried.

The witch-panic phenomenon reached the more remote parts of Europe as well as North America later in the 17th century, among them being the

Salzburg witch trials, the Swedish

Tors├źker witch trials and, in 1692, the

Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Not everyone wh ...

in

Colonial New England.

Decline of the trials: 1630ŌĆō1750

There had never been a lack of skepticism regarding the trials. In 1635, the authorities of the

Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally , was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes according ...

acknowledged its own trials had "found scarcely one trial conducted legally". In the middle of the 17th century, the difficulty in proving witchcraft according to the legal process contributed to

Rothenburg (Germany) following advice to treat witchcraft cases with caution.

Although the witch trials had begun to fade out across much of Europe by the mid-17th century, they continued on the fringes of Europe and in the American Colonies. In the Nordic countries, the late 17th century saw the peak of the trials in a number of areas: the

Tors├źker witch trials of

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

(1674), where 71 people were executed for witchcraft in a single day, the peak of witch hunting in Swedish Finland,

and the

Salzburg witch trials in Austria (where 139 people were executed from 1675 to 1690).

The 1692

Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Not everyone wh ...

were a brief outburst of witch panic that occurred in the

New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

when the practice was waning in Europe. In the 1690s, Winifred King Benham and her daughter Winifred were thrice tried for witchcraft in

Wallingford, Connecticut

Wallingford is a town in New Haven County, Connecticut, New Haven County, Connecticut, United States, centrally located between New Haven, Connecticut, New Haven and Hartford, Connecticut, Hartford, and Boston and New York City. The town is part ...

, the last of such trials in

New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. Even though they were found innocent, they were compelled to leave Wallingford and settle in

Staten Island, New York

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

. In 1706,

Grace Sherwood of

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

was tried by ducking and jailed for allegedly being a witch.

Rationalist historians in the 18th century came to the opinion that the use of torture had resulted in erroneous testimony.

In 1712, Rabbi Hirsch Fr├żnkel was convicted of witchcraft after completion of an inquisition by the Theological & Legal Faculties at the University of Aldorf. Rabbi Fr├żnkel was a self-avowed Kabbalist, a follower the ancient Jewish tradition of mystical interpretation of the Bible. The Fr├żnkel witchtrial was one of the first convictions obtained without the use of spectral evidence or confession obtained through torture. Fr├żnkel was sentenced to life imprisonment and spent twenty-four years in solitary confinement in the tower of Schwabach.

In France, scholars have found that with increased fiscal capacity and a stronger central government, the witchcraft accusations began to decline. The witch trials that occurred there were symptomatic of a weak legal system and "witches were most likely to be tried and convicted in regions where magistrates departed from established legal statutes".

During the early 18th century, the practice subsided.

Jane Wenham was among the last subjects of a typical witch trial in England in 1712, but was pardoned after her conviction and set free. The last execution for witchcraft in England took place in 1716, when

Mary Hicks and her daughter Elizabeth were hanged.

Janet Horne was executed for witchcraft in Scotland in 1727. The

Witchcraft Act 1735 (

9 Geo. 2. c. 5) put an end to the traditional form of witchcraft as a legal offense in Britain.

Those accused under the new act were restricted to those that pretended to be able to conjure spirits (generally being the most dubious professional fortune tellers and mediums), and punishment was light.

In Austria,

Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa (Maria Theresia Walburga Amalia Christina; 13 May 1717 ŌĆō 29 November 1780) was the ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position suo jure, in her own right. She was the ...

outlawed witch-burning and torture in 1768. The last capital trial, that of

Maria Pauer occurred in 1750 in Salzburg, which was then outside the Austrian domain.

Sporadic witch-hunts after 1750

In the late 18th century the practice of witchcraft had ceased to be considered a criminal offense throughout Europe, but there are a number of trials which, while technically not witch trials, are suspected to have involved a belief in witches. In 1782,

Anna G├Čldi was executed in

Glarus

Glarus (; ; ; ; ) is the capital of the canton of Glarus in Switzerland. Since 1 January 2011, the municipality of Glarus incorporates the former municipalities of Ennenda, Netstal and Riedern.[Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...]

. Officially she was executed for "poisoning" (her employer, who believed that she had practiced witchcraft on his daughter)ŌĆöa ruling at the time widely denounced throughout Switzerland and Germany as

judicial murder

Judicial murder is the intentional and premeditated killing of an innocent person by means of capital punishment; therefore, it is a subset of wrongful execution. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' describes it as "death inflicted by process of law ...

. Like Anna G├Čldi,

Barbara Zdunk was executed in 1811 in

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, not technically for witchcraft, but for arson. In Poland, the

Doruch├│w witch trials occurred in 1783, and two additional women were executed for sorcery. They were tried by a legal court, but with dubious legitimacy.

Despite the official ending of the trials for witchcraft, there would still be occasional and unofficial

witch-hunt

A witch hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or Incantation, incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the ...

s and killings of those who were accused of practicing witchcraft in parts of Europe, such as the killings of

Anna Klemens

Anna Klemens (1718ŌĆō1800) was a Danish murder victim and an alleged witch. She was lynched and accused of sorcery in Brigsted at Horsens in DenmarkŌĆōNorway, a lynching considered to be the last witch lynching in her country and, most likely, ...

in Denmark (1800),

Krystyna Ceynowa in Poland (1836), and

Dummy, the Witch of Sible Hedingham in England (1863). In France, there was sporadic violence and there was even murder in the 1830s, with one woman reportedly burnt in a village square in

Nord.

In the 1830s, a prosecution for witchcraft was commenced against a man in Fentress County, Tennessee, either named Joseph or William Stout, based upon his alleged influence over the health of a young woman. The case against the supposed witch was dismissed upon the failure of the alleged victim, who had sworn out a warrant against him, to appear for the trial. However, some of his other accusers were convicted on criminal charges for their part in the matter, and various libel actions were brought.

[History of Fentress County, Tennessee, Albert R. Hogue, compiled by the Fentress County Historical Society]

p. 67transcription

In 1895,

Bridget Cleary was beaten and burned to death by her husband in Ireland because he suspected that fairies had taken the real Bridget and

replaced her with a witch.

The killing of people who were suspected of performing malevolent sorcery against their neighbors continued into the 20th and 21st centuries. In 1997, two Russian farmers killed a woman and injured five members of her family because they believed that the woman and her relatives had used folk magic against them.

It has been reported that between 2005 and 2011, more than 3,000 people were killed for allegedly being witches by lynch mobs in Tanzania. Witchcraft was officially a crime in Papua New Guinea from 1971 until 2013.

Procedures and punishments

Evidence

Peculiar standards applied to witchcraft allowing certain types of evidence "that are now ways relating Fact, and done many Years before". There was no possibility to offer

alibi

An alibi (, from the Latin, '' alib─½'', meaning "somewhere else") is a statement by a person under suspicion in a crime that they were in a different place when the offence was committed. During a police investigation, all suspects are usually a ...

as a defense because witchcraft did not require the presence of the accused at the scene. Witnesses were called to testify to motives and effects because it was believed that witnessing the invisible force of witchcraft was impossible: "half proofes are to be allowed, and are good causes of suspicion". The sole identifier of a witch was the Devil's mark. A scar, given to a witch by the devil, could be anywhere on the body. However, in order to find this scar, the body had to be thoroughly examined. This lack of a recognizable feature led to flexibility. This flexibility enabled the phenomenon of witches to expand, solidifying the fear that witches are a danger that could be within anyone, anywhere.

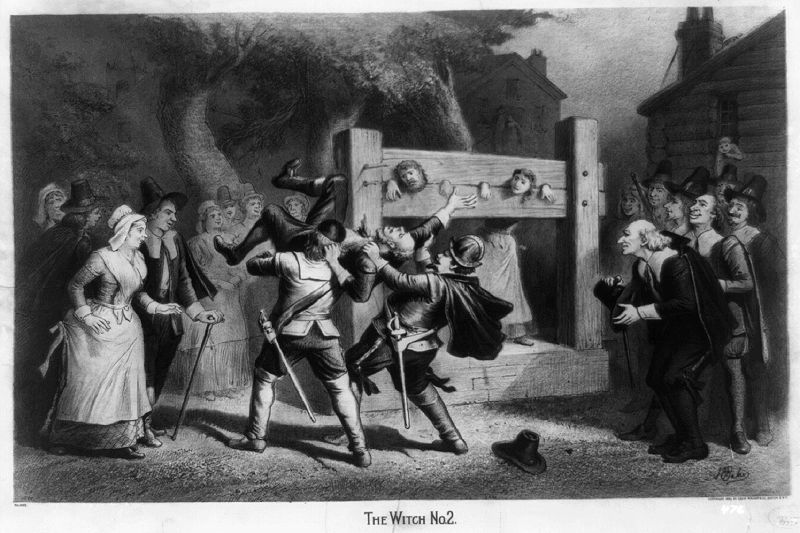

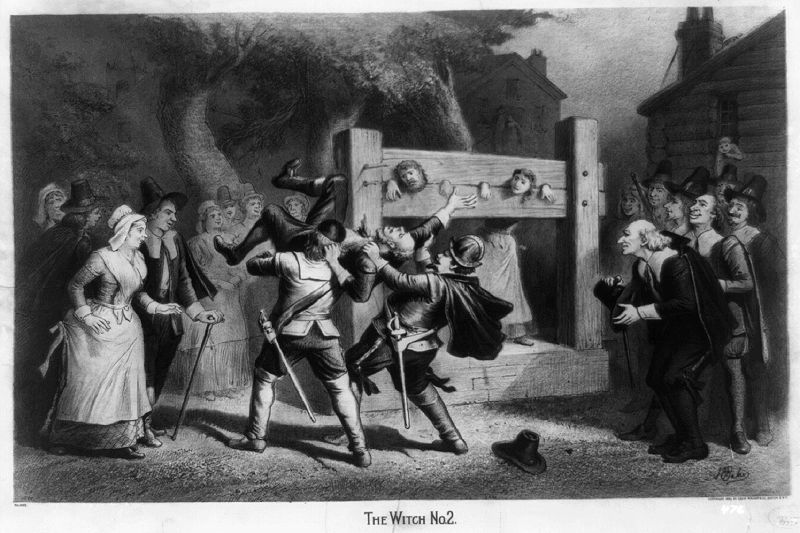

Punishments

A variety of different punishments were employed for those found guilty of witchcraft, including imprisonment, flogging, fines, or exile. Non-capital punishment, especially for a first offence, was most common in England. Prior to 1542, Church courts dealt with most cases in England and most sanctions were directed more to penance and atonement than harsh punishments. Often the guilty party was ordered to attend the parish church, wearing a white sheet and carrying a wand, and swear to lead a reformed life. The

Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

's book of

Exodus (22:17) states, "Thou shalt not permit a sorceress to live". Many faced

capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

for witchcraft, either by burning at the stake, hanging, or beheading. Similarly, in New England, people convicted of witchcraft were hanged. Meanwhile, in the Middle Ages, heresy became a heinous crime, warranting severe punishment, so when one was accused of being a witch they were thus labeled as a heretic. If accused of witchcraft, the accused was forced to confess, even if they were innocent, through brutal torture, just to in the end be killed for their crimes. In certain instances, the clergy became truly concerned about the souls they were executing. Therefore, they decided to burn the accused witches alive in order to "save them".

Interrogations and torture

Various acts of

torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

were used against accused witches to coerce confessions and cause them to provide names of alleged co-conspirators. Most historians agree that the majority of those persecuted in these witch trials were innocent of any involvement in Devil worship. The torture of witches began to increase in frequency after 1468, when the Pope declared witchcraft to be and thereby removed all legal limits on the application of torture in cases where evidence was difficult to find.

In Italy, an accused witch was deprived of sleep for periods up to forty hours. This technique was also used in England, but without a limitation on time.

[Camille Naish, ''Death Comes to the Maiden: Sex and Execution 1431ŌĆō1933'' (London: Routledge, 1991), p. 27.] Sexual humiliation was used, such as forced sitting on red-hot stools with the claim that the accused woman would not perform sexual acts with the devil. In most cases, those who endured the torture without confessing were released.

The use of torture has been identified as a key factor in converting the trial of one accused witch into a wider

social panic, as those being tortured were more likely to accuse a wide array of other local individuals of also being witches.

Estimates of the total number of executions

The scholarly consensus on the total number of executions for witchcraft ranges from 40,000 to 60,000

[. Scarre and Callow (2001) put forward 40,000 as an estimate for the number killed. Levack (2006) came to an estimate of 45,000. Levack, Brian (2006). ''The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe'' Third Edition. Longman. Page 23. Hutton (2010) estimated that the numbers were between 40,000ŌĆō50,000, Wolfgang Behringer and Lyndal Roper had independently calculated the number as being between 50,000ŌĆō60,000.(; ) In an earlier unpublished essay, Hutton counted local estimates, and in areas where estimates were unavailable attempted to extrapolate from nearby regions with similar demographics and attitudes towards witch hunting. .

] (not including unofficial lynchings of accused witches, which went unrecorded but are nevertheless believed to have been somewhat rare in the

Early Modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

). It would also have been the case that various individuals would have died as a result of the unsanitary conditions of their imprisonment, but again this is not recorded within the number of executions.

Attempts at estimating the total number of executions for witchcraft have a history going back to the end of the period of witch-hunts in the 18th century. A scholarly consensus only emerges in the second half of the 20th century, and historical estimates vary wildly depending on the method used. Early estimates tend to be highly exaggerated, as they were still part of rhetorical arguments against the persecution of witches rather than purely historical scholarship.

Notably, a figure of nine million victims was given by

Gottfried Christian Voigt in 1784 in an argument criticizing

Voltaire

Fran├¦ois-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

's estimate of "several hundred thousand" as too low. Voigt's number has shown remarkably resilient as an influential

popular myth, surviving well into the 20th century, especially in

feminist and neo-pagan literature. In the 19th century, some scholars were agnostic, for instance,

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 ŌĆō 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He formulated Grimm's law of linguistics, and was the co-author of the ''Deutsch ...

(1844) talked of "countless" victims and

Charles Mackay (1841) named "thousands upon thousands". By contrast, a popular news report of 1832 cited a number of 3,192 victims "in Great Britain alone". In the early 20th century, some scholarly estimates on the number of executions still ranged in the hundreds of thousands. The estimate was only reliably placed below 100,000 in scholarship of the 1970s.

Causes and interpretations

Regional differences

There were many regional differences in the manner in which the witch trials occurred. The trials themselves emerged sporadically, flaring up in some areas but neighbouring areas remaining largely unaffected. In general, there seems to have been less witch-phobia in

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and the papal lands of

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

in comparison to

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

.

There was much regional variation within the

British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

. In Ireland, for example, there were few trials.

There are particularly important differences between the English and continental witch-hunting traditions. In England the use of torture was rare and the methods far more restrained. The country formally permitted it only when authorized by the monarch, and no more than 81 torture warrants were issued (for all offenses) throughout English history. The death toll in Scotland dwarfed that of England. It is also apparent from an episode of English history, that during the civil war in the early 1640s, witch-hunters emerged, the most notorious of whom was

Matthew Hopkins

Matthew Hopkins ( 1620 ŌĆō 12 August 1647) was an English witch-hunter whose career flourished during the English Civil War. He was mainly active in East Anglia and claimed to hold the office of Witchfinder General, although that titl ...

from

East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

and proclaimed himself the "Witchfinder General".

Italy has had fewer witchcraft accusations, and even fewer cases where witch trials ended in execution. In 1542, the establishment of the Roman Catholic

Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

effectively restrained secular courts under its influence from liberal application of torture and execution. The methodological Instructio, which served as an "appropriate" manual for witch hunting, cautioned against hasty convictions and careless executions of the accused. In contrast with other parts of Europe, trials by the Venetian Holy Office never saw conviction for the crime of malevolent witchcraft, or "maleficio". Because the notion of diabolical cults was not credible to either popular culture or Catholic inquisitorial theology, mass accusations and belief in Witches' Sabbath never took root in areas under such inquisitorial influence.

The number of people tried for witchcraft between the years of 1500ŌĆō1700 (by region) include: Holy Roman Empire: 50,000 Poland: 15,000 Switzerland: 9,000 French Speaking Europe: 10,000 Spanish and Italian peninsulas: 10,000 Scandinavia: 4,000.

Socio-political turmoil

Various suggestions have been made that the witch trials emerged as a response to socio-political turmoil in the Early Modern world. One form of this is that the prosecution of witches was a reaction to a disaster that had befallen the community, such as crop failure, war, or disease. For instance, Midelfort suggested that in southwestern Germany, war and famine destabilised local communities, resulting in the witch prosecutions of the 1620s. Behringer also suggests an increase in witch prosecutions due to socio-political destabilization, stressing the Little Ice Age's effects on food shortages, and the subsequent use of witches as scapegoats for consequences of climatic changes.

The Little Ice Age, lasting from about 1300 to 1850, is characterized by temperatures and precipitation levels lower than the 1901ŌĆō1960 average. Historians such as Wolfgang Behringer, Emily Oster, and

Hartmut Lehmann argue that these cooling temperatures brought about crop failure, war, and disease, and that witches were subsequently blamed for this turmoil.

Historical temperature indexes and witch trial data indicate that, generally, as temperature decreased during this period, witch trials increased.

Additionally, the peaks of witchcraft persecutions overlap with hunger crises that occurred in 1570 and 1580, the latter lasting a decade.

Problematically for these theories, it has been highlighted that, in that region, the witch hunts declined during the 1630s, at a time when the communities living there were facing increased disaster as a result of plague, famine, economic collapse, and the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

. Furthermore, this scenario would clearly not offer a universal explanation, for trials also took place in areas which were free from war, famine, or pestilence. Additionally, these theoriesŌĆöparticularly Behringer's ŌĆöhave been labeled as oversimplified.

Although there is evidence that the Little Ice Age and subsequent famine and disease was likely a contributing factor to increase in witch persecution, Durrant argues that one cannot make a direct link between these problems and witch persecutions in all contexts.

Moreover, the

average age at first marriage had gradually risen by the late sixteenth century; the population had stabilized after a period of growth, and availability of jobs and land had lessened. In the last decades of the century, the age at marriage had climbed to averages of 25 for women and 27 for men in England and the Low Countries, as more people married later or remained unmarried due to lack of money or resources and a decline in living standards, and these averages remained high for nearly two centuries and averages across Northwestern Europe had done likewise. The

convents were closed during the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

, which displaced many nuns. Many communities saw the proportion of unmarried women climb from less than 10% to 20% and in some cases as high as 30%, whom few communities knew how to accommodate economically. Miguel (2003) argues that witch killings may be a process of eliminating the financial burdens of a family or society, via elimination of the older women that need to be fed, and an increase in unmarried women would enhance this process.

Catholic versus Protestant conflict

The English historian

Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton, (15 January 1914 ŌĆō 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History (Oxford), Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Rope ...

advocated the idea that the witch trials emerged as part of the conflicts between Roman Catholics and Protestants in Early Modern Europe. A 2017 study in the ''

Economic Journal'', examining "more than 43,000 people tried for witchcraft across 21 European countries over a period of five-and-a-half centuries", found that "more intense religious-market contestation led to more intense witch-trial activity. And, compared to religious-market contestation, the factors that existing hypotheses claim were important for witch-trial activityŌĆöweather, income, and

state capacity

State capacity is the ability of a government to accomplish policy goals, either generally or in reference to specific aims. More narrowly, state capacity often refers to the ability of a state to collect taxes, enforce law and order, and provide p ...

ŌĆöwere not."

Until recently, this theory received limited support from other experts in the subject. This is because there is little evidence that either Roman Catholics were accusing Protestants of witchcraft, or that Protestants were accusing Roman Catholics. Furthermore, the witch trials regularly occurred in regions with little or no inter-denominational strife, and which were largely religiously homogeneous, such as

Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

,

Lowland Scotland

The Lowlands ( or , ; , ) is a cultural and historical region of Scotland.

The region is characterised by its relatively flat or gently rolling terrain as opposed to the mountainous landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. This area includes ci ...

,

Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rh├┤ne exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

,

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, and the

Spanish Basque Country. There is also some evidence, particularly from the Holy Roman Empire, in which adjacent Roman Catholic and Protestant territories were exchanging information on alleged local witches, viewing them as a common threat to both. Additionally, many prosecutions were instigated not by the religious or secular authorities, but by popular demands from within the population, thus making it less likely that there were specific inter-denominational reasons behind the accusations.

The more recent research from the 2017 study in the ''

Economic Journal'' argues that both Catholics and Protestants used the hunt for witches, regardless of the witch's denomination, in competitive efforts to expand power and influence.

In south-western Germany, between 1561 and 1670, there were 480 witch trials. Of the 480 trials that took place in southwestern Germany, 317 occurred in Catholic areas and 163 in Protestant territories. During the period from 1561 to 1670, at least 3,229 persons were executed for witchcraft in the German Southwest. Of this number, 702 were tried and executed in Protestant territories and 2,527 in Catholic territories.

Translation from the Hebrew: Witch or poisoner?

It has been argued that a translation choice in the King James Bible justified "horrific human rights violations and fuel

dthe epidemic of witchcraft accusations and persecution across the globe". The translation issue concerned Exodus 22:18, "do not suffer a ...

ither 1) poisoner ''or'' 2) witch...to live," Both the King James and the Geneva Bible, which precedes the King James version by 51 years, chose the word "witch" for this verse. The proper translation and definition of the Hebrew word (''m╔ÖßĖĄa┼Ī┼Ī├¬p╠ä─üh'') in Exodus 22:18 was much debated during the time of the trials and witch-phobia.

1970s folklore emphasis

From the 1970s onward, there was a "massive explosion of scholarly enthusiasm" for the study of the Early Modern witch trials. This was partly because scholars from a variety of different disciplines, including

sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

,

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

,

cultural studies

Cultural studies is an academic field that explores the dynamics of contemporary culture (including the politics of popular culture) and its social and historical foundations. Cultural studies researchers investigate how cultural practices rel ...

,

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

,

philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is the branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. Amongst its central questions are the difference between science and non-science, the reliability of scientific theories, ...

,

criminology

Criminology (from Latin , 'accusation', and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from ╬╗Žī╬│╬┐Žé ''logos'', 'word, reason') is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behaviou ...

,

literary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, m ...

, and

feminist theory

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, fictional, or Philosophy, philosophical discourse. It aims to understand the nature of gender inequality. It examines women's and men's Gender role, social roles, experiences, intere ...

, all began to investigate the phenomenon and brought different insights to the subject. This was accompanied by analysis of the trial records and the socio-cultural contexts on which they emerged, allowing for varied understanding of the trials.

Functionalism

Inspired by ethnographically recorded witch trials that anthropologists observed happening in non-European parts of the world, various historians have sought a functional explanation for the Early Modern witch trials, thereby suggesting the social functions that the trials played within their communities. These studies have illustrated how accusations of witchcraft have played a role in releasing social tensions or in facilitating the termination of personal relationships that have become undesirable to one party.

Feminist interpretations

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, various

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

interpretations of the witch trials have been offered and published. One of the earliest individuals to do so was the American

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage ( Joslyn; March 24, 1826 – March 18, 1898) was an American writer and activist. She is mainly known for her contributions to women's suffrage in the United States, but also campaigned for Native American rights, aboli ...

, a writer who was deeply involved in the

first-wave feminist movement for

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

. In 1893, she published the book ''Woman, Church and State'', which was criticized as "written in a tearing hurry and in time snatched from a political activism which left no space for original research".

[ Hutton 1999. p. 141.] Likely influenced by the works of

Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 ŌĆō 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

about the witch-cult, she claimed that the witches persecuted in the Early Modern period were pagan priestesses adhering to an

ancient religion venerating a Great Goddess. She also repeated the erroneous statement, taken from the works of several German authors, that nine million people had been killed in the witch hunt.

The United States has become the centre of development for these feminist interpretations.

In 1973, two American second-wave feminists,

Barbara Ehrenreich

Barbara Ehrenreich (, ; ; August 26, 1941 ŌĆō September 1, 2022) was an American author and political activist. During the 1980s and early 1990s, she was a prominent figure in the Democratic Socialists of America. She was a widely read and aw ...

and

Deirdre English

Deirdre English (b.1948) is an American journalist who has written and edited work on a wide array of subjects related to investigative reporting, cultural politics, gender studies, and public policy. The former Editor-in-Chief of '' Mother Jones ...

, published an extended pamphlet in which they put forward the idea that the women persecuted had been the traditional healers and midwives of the community, who were being deliberately eliminated by the male medical establishment. This theory disregarded the fact that the majority of those persecuted were neither healers nor midwives, and that in various parts of Europe these individuals were commonly among those encouraging the persecutions. In 1994, Anne Llewellyn Barstow published her book ''Witchcraze'', which was later described by Scarre and Callow as "perhaps the most successful" attempt to portray the trials as a systematic male attack on women.

Other feminist historians have rejected this interpretation of events; historian

Diane Purkiss described it as "not politically helpful" because it constantly portrays women as "helpless victims of patriarchy" and thus does not aid them in contemporary feminist struggles. She also condemned it for factual inaccuracy by highlighting that radical feminists adhering to it ignore the

historicity

Historicity is the historical actuality of persons and events, meaning the quality of being part of history instead of being a historical myth, legend, or fiction. The historicity of a claim about the past is its factual status. Historicity deno ...

of their claims, instead promoting it because it is perceived as authorising the continued struggle against patriarchal society. She asserted that many radical feminists nonetheless clung to it because of its "mythic significance" and firmly delineated structure between the oppressor and the oppressed.

Male and Female conflict and reaction to earlier feminist studies

An estimated 75% to 85% of those accused in the early modern witch trials were women,

[Per , "Records suggest that in Europe, as a whole, about 80 per cent of trial defendants were women, though the ratio of women to men charged with the offence varied from place to place, and often, too, in one place over time."] and there is certainly evidence of

misogyny

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against Woman, women or girls. It is a form of sexism that can keep women at a lower social status than Man, men, thus maintaining the social roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been wide ...

on the part of those persecuting witches, evident from quotes such as "

t isnot unreasonable that this scum of humanity,

itches should be drawn chiefly from the feminine sex" (

Nicholas R├®my, c. 1595) or "The Devil uses them so, because he knows that women love carnal pleasures, and he means to bind them to his allegiance by such agreeable provocations." Scholar

Kurt Baschwitz, in his first monography on the subject (in Dutch, 1948), mentions this aspect of the witch trials even as ''"a war against old women"''.

Nevertheless, it has been argued that the supposedly misogynistic agenda of works on witchcraft has been greatly exaggerated, based on the selective repetition of a few relevant passages of the ''Malleus maleficarum''. There are various reasons as to why this was the case. In Early Modern Europe, it was widely believed that women were less intelligent than men and more susceptible to sin.

Many modern scholars argue that the witch hunts cannot be explained simplistically as an expression of male misogyny, as indeed women were frequently accused by other women,

[ Gibbons 1998.] to the point that witch-hunts, at least at the local level of villages, have been described as having been driven primarily by "women's quarrels".

["In Lorraine the majority were men, particularly when other men were on trial, yet women did testify in large numbers against other women, making up 43 per cent of witnesses in these cases on average, and predominating in 30 per cent of them.", Briggs, 'Witches & Neighbors: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft', p. 264 (1998). "It appears that women were active in building up reputations by gossip, deploying counter-magic and accusing suspects; crystallization into formal prosecution, however, needed the intervention of men, preferably of fairly high status in the community.", ibid., p. 265. "The number of witchcraft quarrels that began between women may actually have been higher; in some cases, it appears that the husband as 'head of household' came forward to make statements on behalf of his wife, although the central quarrel had taken place between her and another woman.", Willis, ''Malevolent Nature'', p. 36 (1995). "In Peter Rushton's examination of slander cases in the Durham church courts, women took action against other women who had labeled them witches in 61 percent of the cases.", ibid., p. 36. "J.A. Sharpe also notes the prevalence of women as accusers in seventeenth-century Yorkshire cases, concluding that 'on a village level witchcraft seems to have been something peculiarly enmeshed in women's quarrels.'14 To a considerable extent, then, village-level witch-hunting was women's work.', ibid., p. 36] Especially at the margins of Europe, in Iceland, Finland, Estonia, and Russia, the majority of those accused were male.

['The widespread division of labour, which conceives of witches as female, and witch-doctors male, can hardly be explained by Christian influence. In some European countries, like Iceland, Finland, and Estonia, the idea of male witchcraft was dominant, and therefore most of the executed witches were male. As Kirsten Hastrup has demonstrated, only one of the twenty-two witches executed in Iceland was female. In Normandy three-quarters of the 380 known witchcraft defendants were male.', Behringer, 'Witches and Witch-Hunts: a global history', p. 39 (2004)]

Barstow (1994) claimed that a combination of factors, including the greater value placed on men as workers in the increasingly wage-oriented economy, and a greater fear of women as inherently evil, loaded the scales against women, even when the charges against them were identical to those against men.

Thurston (2001) saw this as a part of the general misogyny of the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods, which had increased during what he described as "the persecuting culture" from which it had been in the Early Medieval.

Gunnar Heinsohn

Gunnar Heinsohn (21 November 1943 ŌĆō 16 February 2023) was a German author, sociologist and economist and professor emeritus at the University of Bremen where he had a chair in social pedagogy from 1984.

Heinsohn published on a wide array of ...

and

Otto Steiger, in a 1982 publication, speculated that witch-hunts targeted women skilled in midwifery specifically in an attempt to extinguish knowledge about

birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

and "repopulate Europe" after the population catastrophe of the

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

; this view has been rejected by mainstream historians. The historian of medicine David Harley criticised the notion of the midwife-witch as a prevalent type of victim of witch hunts and commented on Heinsohn and Steiger as belonging to a set of polemicists who misportrayed the history of midwifery.

Were there any sorts of witches?

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the common belief among the educated sectors of the European populace was that there had never been any genuine

cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

of witches and all of those people who were persecuted and executed as such were innocent of the crime of witchcraft. However, at this time, various scholars suggested that there had been a real cult that had been persecuted by the Christian authorities, and it had pre-Christian origins. The first person to advance this theory was the German Professor of Criminal Law

Karl Ernst Jarcke of the

University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

, who put forward the idea in 1828; he suggested that witchcraft had been a pre-Christian German religion that had degenerated into Satanism. Jarcke's ideas were picked up by the German historian Franz Josef Mone in 1839, although he argued that the cult's origins were Greek rather than Germanic.

In 1862, the Frenchman

Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 ŌĆō 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

published ''

La Sorciere'', in which he put forth the idea that the witches had been following a pagan religion. The theory achieved greater attention when it was taken up by the Egyptologist

Margaret Murray

Margaret Alice Murray (13 July 1863 ŌĆō 13 November 1963) was an Anglo-Indian Egyptologist, archaeologist, anthropologist, historian, and folklorist. The first woman to be appointed as a lecturer in archaeology in the United Kingdom, sh ...

, who published both ''The Witch-Cult in Western Europe'' (1921) and ''The God of the Witches'' (1931) in which she claimed that the witches had been following a pre-Christian religion which she termed "the witch-cult" and "ritual witchcraft".

Murray claimed that this faith was devoted to a pagan

Horned God

The Horned God is one of the two primary deities found in Wicca and some related forms of Neopaganism.

The term ''Horned God'' itself predates Wicca, and is an early 20th-century syncretism, syncretic term for a horned or antlered anthropomorp ...

and involved the celebration of four Witches' Sabbaths each year:

Halloween

Halloween, or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve), is a celebration geography of Halloween, observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christianity, Western Christian f ...

,

Imbolc

Imbolc or Imbolg (), also called Saint Brigid's Day (; ; ), is a Gaels, Gaelic traditional festival on 1 February. It marks the beginning of Spring (season), spring, and in Christianity, it is the calendar of saints, feast day of Brigid of Kild ...

,

Beltane

Beltane () or ''Bealtaine'' () is the Gaels, Gaelic May Day festival, marking the beginning of summer. It is traditionally held on 1 May, or about midway between the March equinox, spring equinox and summer solstice. Historically, it was widely ...

, and

Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh, Lughnasa or L├║nasa ( , ) is a Gaels, Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. Traditionally, it is held on 1 August, or abo ...

. However, the majority of scholarly reviews of Murray's work produced at the time were largely critical, and her books never received support from experts in the Early Modern witch trials. Instead, from her early publications onward many of her ideas were challenged by those who highlighted her "factual errors and methodological failings".

However, the publication of the Murray thesis in the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' made it accessible to "journalists, film-makers popular novelists and thriller writers", who adopted it "enthusiastically". Influencing works of literature, it inspired writings by

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley ( ; 26 July 1894 ŌĆō 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. His bibliography spans nearly 50 books, including non-fiction novel, non-fiction works, as well as essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the ...

and

Robert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 ŌĆō 7 December 1985) was an English poet, soldier, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were b ...

. Subsequently, in 1939, an English occultist named

Gerald Gardner

Gerald Brosseau Gardner (13 June 1884 ŌĆō 12 February 1964), also known by the craft name Scire, was an English Wiccan, author, and amateur anthropology, anthropologist and archaeology, archaeologist. He was instrumental in bringing the Moder ...