Peace Ship on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

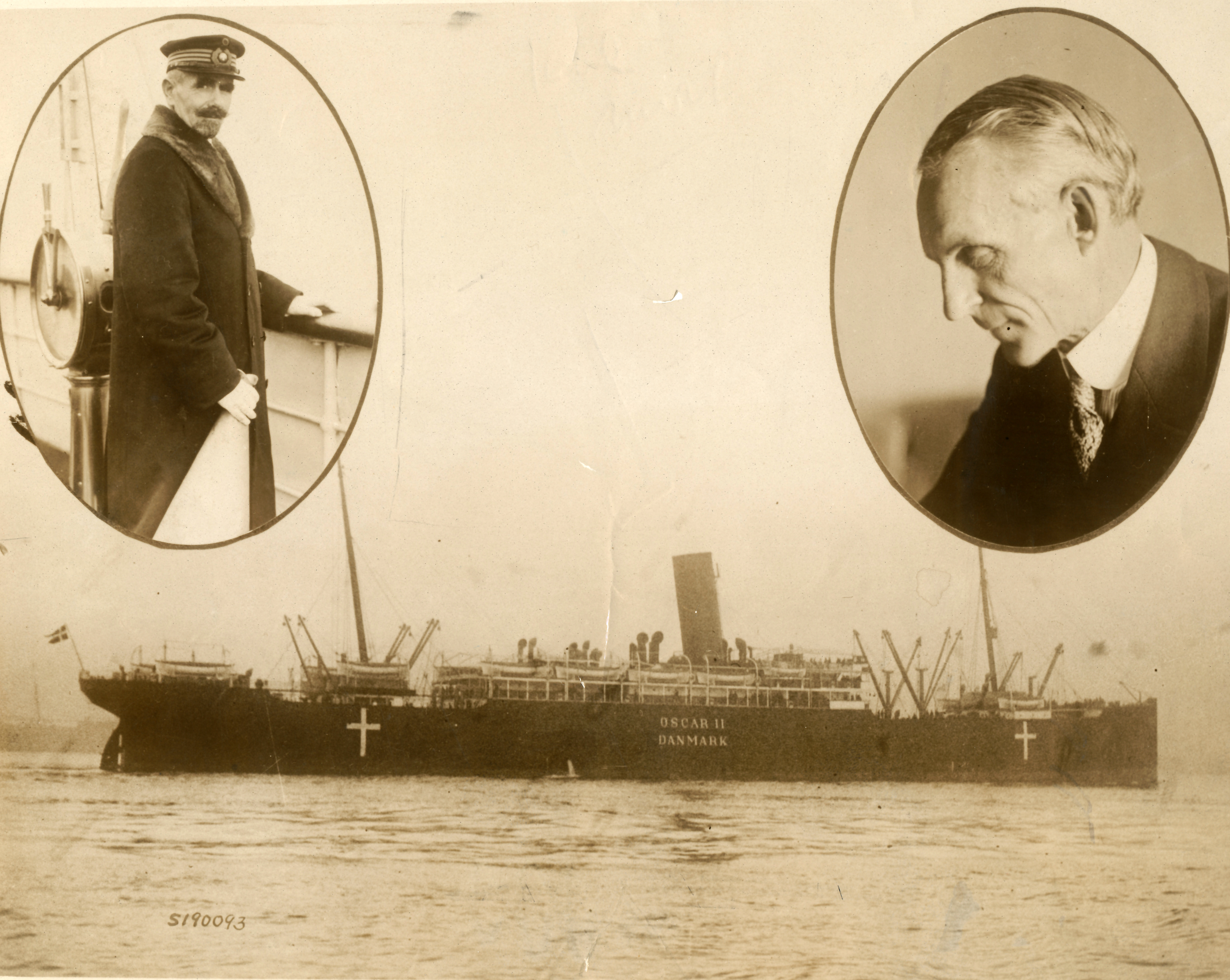

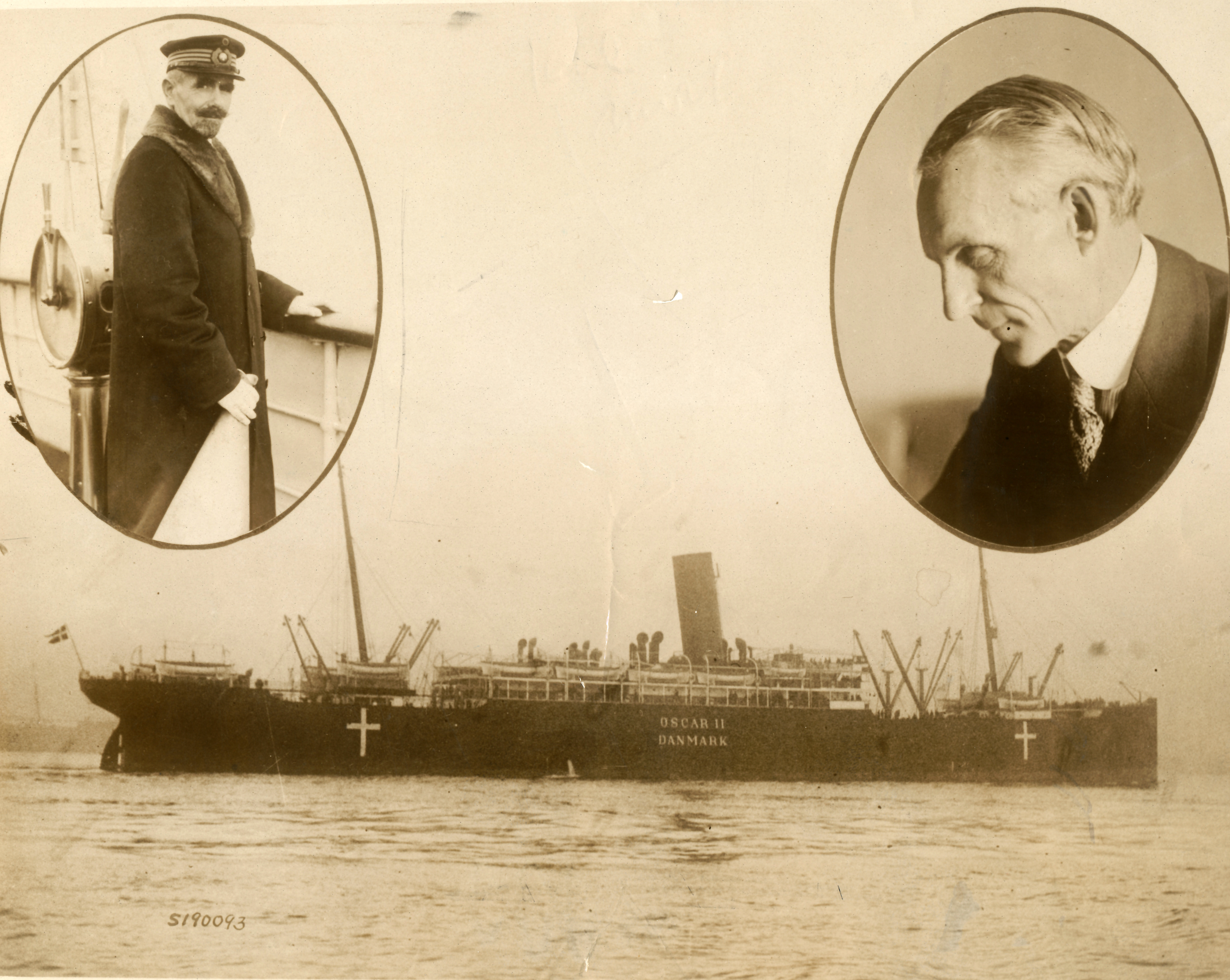

The Peace Ship was the common name for the ocean liner ''Oscar II'', on which American industrialist

The Peace Ship was the common name for the ocean liner ''Oscar II'', on which American industrialist

Ford initially sought President

Ford initially sought President

The ''Oscar II'' set sail from

The ''Oscar II'' set sail from

Initially, the press response to the Peace Ship was respectful. ''

Initially, the press response to the Peace Ship was respectful. ''https://doi.org/10.5342/michhistrevi.36.1.71 .

"Ford peace expedition"

''Information: A digest of current events covering 1915''. January 1916. {{Authority control Opposition to World War I Henry Ford World War I passenger ships of the United States

The Peace Ship was the common name for the ocean liner ''Oscar II'', on which American industrialist

The Peace Ship was the common name for the ocean liner ''Oscar II'', on which American industrialist Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

organized and launched his 1915 amateur peace mission to Europe; Ford chartered the ''Oscar II'' and invited prominent peace activists to join him. He hoped to create enough publicity to prompt the belligerent nations to convene a peace conference and mediate an end to World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, but the mission was widely mocked by the press, which referred to the ''Oscar II'' as the "Ship of Fools" as well as the "Peace Ship". Infighting between the activists, mockery by the press contingent aboard, and an outbreak of influenza marred the voyage. Five days after ''Oscar II'' arrived in Norway, a beleaguered and physically ill Ford abandoned the mission and returned to the United States. The peace mission was unsuccessful, which reinforced Ford's reputation as a supporter of unusual causes. The ship was named after the former Swedish Monarch

The monarchy of Sweden is centred on the monarchical head of state of Sweden,See the #IOG, Instrument of Government, Chapter 1, Article 5. by law a constitutional monarchy, constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system.Parl ...

H.M. King Oscar II of Sweden (until 1905 also King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty king ...

) who, according to Ford, was a peaceloving monarch.

Background

In early 1915, Ford began to express pacifist sentiments publicly and to denounce the ongoing war in Europe. Ford made an announcement to the press that he would fund an effective peace initiative that would assist in mediating and ending World War I. He principally offered one million and later increased it to ten million dollars.Wenger, Beth S. (1990). "Radical Politics in a Reactionary Age: The Unmaking of Rosika Schwimmer, 1914-1930". ''Journal of Women's History''. 2 (2): 66–99. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0133.ISSN

An International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) is an eight-digit to uniquely identify a periodical publication (periodical), such as a magazine. The ISSN is especially helpful in distinguishing between serials with the same title. ISSNs a ...

1527-2036. Rosika Schwimmer, Hungarian activist, heard the news through a colleague, Louis P. Lochner, fellow feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

, pacifist, and acting secretary of the International Federation of Students, who soon set up a meeting. By November, Lochner and Schwimmer approached Ford, now commonly recognized as a pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

, with a proposal to launch an amateur diplomatic mission to Europe to broker an end to World War I. Known as a radical, Schwimmer was well respected on the Eastern European front, accredited with the founding of the Women’s Peace Party, the Campaign for World Government, and the International Criminal Court as well as participating in various international conferences. This project aligned with her her known projections and ambitions. Schwimmer claimed to possess diplomatic correspondence that proved that the European powers were willing to negotiate, which was an outright fabrication. Nevertheless, Ford agreed to finance a peace campaign.

Ford initially sought President

Ford initially sought President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's endorsement of his diplomatic undertaking. Ford and Lochner secured a meeting with Wilson at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

and proposed for Wilson to commission Ford's mission to Europe officially. Although Wilson was sympathetic to Ford's aims, he declined the offer on the ground that the venture was most unlikely to succeed.

Disappointed by Wilson's response, Ford told Lochner that Wilson was a "small man."

Ford was undeterred by Wilson's refusal to endorse the expedition and planned it as a private delegation to Europe. On 24 November 1915, he announced to a New York City press conference that he had chartered the ocean liner ''Oscar II'' for a diplomatic mission to Europe, and he invited the most prominent pacifists of the age to join him. Among those invited were Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

, William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

, Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

, and John Wanamaker.

Addams, Bryan, Edison, and Wanamaker all declined. However, a number of noted peace activists joined the voyage, such as suffragette Inez Milholland and publisher S. S. McClure. Also aboard the ship were more than 40 reporters and Ford's friend, Rev. Samuel Marquis.

Mission to Europe

The ''Oscar II'' set sail from

The ''Oscar II'' set sail from Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; ) is a City (New Jersey), city in Hudson County, New Jersey, Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Hoboken is part of the New York metropolitan area and is the site of Hoboken Terminal, a major transportation hub. As of the ...

, on 4 December 1915, amid an atmosphere that the press later derided as circus-like. A crowd of about 15,000 watched the ''Oscar II'' depart from the harbor while a band played " I Didn't Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier."

Just before the ship's departure, a prankster placed a cage containing two squirrels and a sign reading "To the Good Ship Nutty" on the ship's gangplank. When the ship departed, a fully dressed man jumped off the pier and attempted to swim after it. The harbor police rescued the man, who identified himself as Mr. Zero, explaining that he was "swimming to reach public opinion."

Infighting among the delegates plagued ''Oscar II'' for much of its journey across the Atlantic. In particular, they quarrelled over the proper response to send to the media after they received news of Wilson's 7 December address to Congress, which called for considerable increases to the US Army and Navy. The majority of delegates signed a resolution that denounced Wilson's policy of military preparedness, but a substantial minority refused to sign the resolution, on the ground that the resolution was unpatriotic.

After the pro-Wilson minority threatened to abandon the mission upon landing in Europe, the two factions denounced each other.

An outbreak of influenza spread through the ship about halfway across the Atlantic, resulting in one person dying of pneumonia and many others being afflicted. Ford himself fell ill and withdrew to his cabin, avoiding reporters. Nevertheless, a group of them barged into his cabin to check on a rumor that he had died.

The Peace Ship arrived at its first destination, Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, on 18 December, receiving a cool reception from the Norwegians, many of whom supported military preparedness and were skeptical towards the ship and its delegates. Ford, still sick with flu, retreated to his room at the Grand Hotel for four days. He met the press in his suite in the evening on 21 December, but he spoke little about the Peace Ship and its mission.

His statement to the press was reported in ''Aftenposten

(; ; stylized as in the masthead) is Norway's largest printed newspaper by circulation as well as Norway's newspaper of record. It is based in Oslo. It sold 211,769 daily copies in 2015 (172,029 printed copies according to University of Bergen ...

'', an Oslo newspaper, and ''Dagens Nyheter

(, ), abbreviated ''DN'', is a daily newspaper in Sweden. It is published in Stockholm and aspires to full national and international coverage, and is widely considered Sweden's newspaper of record

A newspaper of record is a major nationa ...

'', a Stockholm morning newspaper, on 22 December. (''Aftenposten'' has a digital version and ''Dagens Nyheter'' is on record on microfilm at the Swedish National Library in Stockholm.)

About then, Samuel Marquis convinced Ford to abandon the Peace Ship, on account of Ford's illness and Schwimmer's failure to produce the documents that supposedly proved that the belligerent nations were ready to mediate.

On 23 December. Ford and Marquis slipped out of their hotel, took the train to Bergen and sailed on the steamer ''Bergensfjord'' back to the United States on 24 December, arriving in New York 2 January 1916.

Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation

Despite Ford's abandonment of the endeavor, the Peace Ship continued its journey around Europe. The Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation began in Stockholm on February 10, 1916, gathering representatives from the United States, Denmark, Holland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland. Lochner was the general secretary of the Conference. The two US delegates were Charles A. Aked and Emily Greene Balch. There was a "Committee of Seven" overseeing the resulting Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation, including Lola Maverick Lloyd. Envoys were sent to England, Germany, and Russia, all ultimately unsuccessful. In autumn of 1916 Schwimmer traveled back to the United States to gather support. Ford continued to pay for the ship's expenses and the Conference until early 1917, when it became clear the US was edging closer to entering the war. In total, the Peace Ship expedition ultimately cost Ford approximately half a million dollars (US$ in ).Response

Initially, the press response to the Peace Ship was respectful. ''

Initially, the press response to the Peace Ship was respectful. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' warned that an immediate peace would entail German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

possession of Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

and part of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, but concluded that Ford's plan would do "as little harm as good". Some newspapers applauded Ford's efforts. '' The New York Herald'' asserted that, "We need more Fords, more peace talks, and less indifference to the greatest crime in the world's history".

After all of Ford's most prominent invitees declined his offer of sailing to Europe, the press reaction turned negative. ''The Baltimore Sun

''The Baltimore Sun'' is the largest general-circulation daily newspaper based in the U.S. state of Maryland and provides coverage of local, regional, national, and international news.

Founded in 1837, the newspaper was owned by Tribune Publi ...

'' noted that "All the amateur efforts of altruistic and notoriety-seeking millionaires only make matters worse" while the ''New York World'' stated that "Henry Ford says he would give all his fortune to end the war. So would many another man. But this is something that money will not do". Other papers openly mocked Ford's amateur peace campaign. The '' Philadelphia Record'' claimed that "Henry Ford's millions have gone to his head". The '' Louisville Courier'' was even more severe, suggesting that Henry Ford carried "cold cream in his head". Even activists who did agree to be a part of the expedition quickly became disappointed with Ford's antics, as his affinity for the press suggested his was more interested in gainings publicity than participating in meaningful mediation planning.

Also critical of Ford's endeavor were former United States Senator Chauncey M. Depew and one- time presidential candidate Alton B. Parker

Alton Brooks Parker (May 14, 1852 – May 10, 1926) was an American judge. He was the Democratic nominee in the 1904 United States presidential election, losing in a landslide to incumbent Republican Theodore Roosevelt.

A native of upstate New ...

. Depew famously commented of the Peace Ship, "In uselessness and absurdity it will stand without an equal". Parker also publicly criticized the peace ship, stating "chances are that his antics will be taken seriously and they will tend to bring us into contempt if not hatred".

Although the press mocked Ford's peace mission, it viewed Ford as a victim of manipulation by the other pacifists aboard the ship. The reporters on the ''Oscar II'' took a liking to Ford and decided that he should be afforded more respect than the rest of his entourage. The correspondent for ''The New York Times'' stated that the reporters on the ship earned "an immense respect and liking for the character and abilities of Henry Ford".

While Ford was able to be generally forgiven and his reputation recovered in the press, the passengers were not given the same courtesy, as the press portrayed the majority of Ford's entourage aboard the ship as buffoons, and ridiculed the delegates for the infighting. The press was exceptionally critical of Rosika Schwimmer, who insisted she had diplomatic correspondence that proved the European powers were open to negotiation, but refused to show these documents to the press. Schwimmer was known to lean into the caretaking feminine stereotype as was characteristic of the Women’s Peace Party during the first world war, however her identity made her a large target in other ways. Her identification as a feminist and Jewish woman led the American public to distrust her campaigns and characters, as the 1920s became more and more defiant to the subversive. Schwimmer responded to her negative treatment by the press by locking them out of the wireless room. Despite this critique, activists aboard the Peace Ship continued their radical campaigns on a number of subjects such as women’s suffrage, civil rights, and education policy, largely undeterred from their altruistic missions.Goodier, Susan. “The Price of Pacifism: Rebecca Shelley and Her Struggle for Citizenship.” Michigan Historical Review, vol. 36, no. 1, 2010, pp. 71–101. JSTOR, Legacy

The Peace Ship's mission was ultimately a failure, producing only inconsequential meetings with "quasi-official representatives" from several European governments. Nevertheless, Ford asserted that the Peace Ship's expedition was successful on the grounds that it stimulated discussions about peace. Ford told the press that the Peace Ship "got people thinking, and when you get them to think they will think right". Despite roundly criticizing the Peace Ship, the press generally treated Ford favorably upon his return from Europe. Even papers that derided the Peace Ship, such as the ''New York American'', often voiced support for Ford's calls for peace. In the following years, Ford continued hisantiwar

An anti-war movement is a social movement in opposition to one or more nations' decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term ''anti-war'' can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during co ...

activism and paid for anti-preparedness advertisements to appear in newspapers across the United States.

References

External links

*"Ford peace expedition"

''Information: A digest of current events covering 1915''. January 1916. {{Authority control Opposition to World War I Henry Ford World War I passenger ships of the United States