Peace Campaigner on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A peace movement is a

A peace movement is a

Although the onset of the

Although the onset of the

The Spirit of June 12

''The Nation'', July 2, 2007. International Day of Nuclear-disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983, at 50 locations across the United States.Harvey Klehr

Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today

Transaction Publishers, 1988, p. 150.1,400 Anti-nuclear protesters arrested

''Miami Herald'', June 21, 1983. In 1986, hundreds of people walked from

''Gainesville Sun'', November 16, 1986. Many

438 "Protesters are Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site"

''The New York Times'', February 6, 1987.

''The New York Times'', April 20, 1992. Forty thousand anti-nuclear and anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York on May 1, 2005, 60 years after the

'' Fox News'', May 2, 2005. The protest was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades. In Britain, there were many protests against the government's proposal to replace the aging Trident weapons system with newer missiles. The largest of the protests had 100,000 participants and, according to polls, 59 percent of the public opposed the move. Lawrence S. Wittner

A rebirth of the anti-nuclear weapons movement? Portents of an anti-nuclear upsurge

''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'', 7 December 2007 The International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament, held in

The anti-Vietnam War peace movement began during the 1960s in the United States, opposing U.S. involvement in the

The anti-Vietnam War peace movement began during the 1960s in the United States, opposing U.S. involvement in the

Gustave Moynier and the peace societies

. In: ''International Review of the Red Cross'' (1996), no. 314, p. 532–550 * Giugni, Marco. ''Social protest and policy change: Ecology, antinuclear, and peace movements in comparative perspective'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 2004). * Hinsley, F. H. ''Power and the Pursuit of Peace: Theory and Practice in the History of Relations between States'' (Cambridge UP, 1967

online

* Howard, Michael. ''The Invention of Peace: Reflections on War and International Order'' (2001

excerpt

* Jakopovich, Daniel. ''Revolutionary Peacemaking: Writings for a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence'' (Democratic Thought, 2019). * Kulnazarova, Aigul, and Vesselin Popovski, eds. ''The Palgrave handbook of global approaches to peace'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019). * Kurtz, Lester R., and Jennifer Turpin, eds. ''Encyclopedia of violence, peace, and conflict'' (Academic Press, 1999). * Marullo, Sam, and John Lofland (sociologist), John Lofland, editors, ''Peace Action in the Eighties: Social Science Perspectives'' (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990). * Moorehead, Caroline. ''Troublesome People: The Warriors of Pacifism'' (Bethesda, MD: Adler & Adler, 1987). * Schlabach, Gerald W. "Christian Peace Theology and Nonviolence toward the Truth: Internal Critique amid Interfaith Dialogue." ''Journal of Ecumenical Studies'' 53.4 (2018): 541–568

online

* Vellacott, Jo. "A place for pacifism and transnationalism in feminist theory: the early work of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom." ''Women History Review'' 2.1 (1993): 23–56

online

* Weitz, Eric. ''A World Divided: The Global Struggle for Human Rights in the Age of Nation States'' (Princeton University Press, 2019)

online reviews

online

* Ceadel, Martin. "The First British Referendum: The Peace Ballot, 1934-5." ''English Historical Review'' 95.377 (1980): 810–839

online

* Chatfield, Charles, ed. ''Peace Movements in America'' (New York: Schocken Books, 1973). * Chatfield, Charles. with Robert Kleidman. ''The American Peace Movement: Ideals and Activism'' (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1992). * Chickering, Roger. ''Imperial Germany and a World Without War: The Peace Movement and German Society, 1892-1914'' (Princeton University Press, 2015). * Clinton, Michael. "Coming to Terms with 'Pacifism': The French Case, 1901–1918." ''Peace & Change'' 26.1 (2001): 1–30. * Cooper, Sandi E. "Pacifism in France, 1889-1914: international peace as a human right." ''French historical studies'' (1991): 359–386

online

* Davis, Richard. "The British Peace Movement in the Interwar Years." ''Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique. French Journal of British Studies'' 22.XXII-3 (2017)

online

* Davy, Jennifer Anne. "Pacifist thought and gender ideology in the political biographies of women peace activists in Germany, 1899-1970: introduction." ''Journal of Women's History'' 13.3 (2001): 34–45. * Eastman, Carolyn, "Fight Like a Man: Gender and Rhetoric in the Early Nineteenth-Century American Peace Movement", ''American Nineteenth Century History'' 10 (Sept. 2009), 247–71. *Fontanel, Jacques. "An underdeveloped peace movement: The case of France." ''Journal of Peace Research'' 23.2 (1986): 175–182. * Hall, Mitchell K., ed. ''Opposition to War: An Encyclopedia of US Peace and Antiwar Movements'' (2 vol. ABC-CLIO, 2018). * Howlett, Charles F., and Glen Zeitzer. ''The American Peace Movement: History and Historiography'' (American Historical Association, 1985). * Kimball, Jeffrey. "The Influence of Ideology on Interpretive Disagreement: A Report on a Survey of Diplomatic, Military and Peace Historians on the Causes of 20th Century U. S. Wars", ''History Teacher'' 17#3 (1984) pp. 355–384 DOI: 10.2307/49314

online

* Laity, Paul. ''The British Peace Movement 1870-1914'' (Clarendon Press, 2002). * Locke, Elsie. ''Peace People: A History of Peace Activities in New Zealand'' (Christchurch, NZ: Hazard Press, 1992). * Lukowitz, David C. "British pacifists and appeasement: the Peace Pledge Union." ''Journal of Contemporary History'' 9.1 (1974): 115–127. * Oppenheimer, Andrew. "West German Pacifism and the Ambivalence of Human Solidarity, 1945–1968." ''Peace & Change'' 29.3‐4 (2004): 353–389

online

* Peace III, Roger C. ''A Just and Lasting Peace: The U.S. Peace Movement from the Cold War to Desert Storm'' (Chicago: The Noble Press, 1991). * Pugh, Michael. "Pacifism and politics in Britain, 1931–1935." ''Historical Journal'' 23.3 (1980): 641–656

online

* Puri, Rashmi-Sudha. ''Gandhi on War & Peace'' (1986); focus on India. * Ritchie, J. M. "Germany–a peace-loving nation? A Pacifist Tradition in German Literature." ''Oxford German Studies'' 11.1 (1980): 76–102. * Saunders, Malcolm. "The origins and early years of the Melbourne Peace Society 1899/1914." ''Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society'' 79.1-2 (1993): 96–114. * Socknat, Thomas P. "Canada's Liberal Pacifists and the Great War." ''Journal of Canadian Studies'' 18.4 (1984): 30–44. * Steger, Manfred B. ''Gandhi's dilemma: Nonviolent principles and nationalist power'' (St. Martin's Press, 2000

online review

* Strong-Boag, Veronica. "Peace-making women: Canada 1919–1939." in ''Women and Peace'' (Routledge, 2019) pp. 170–191. * Talini, Giulio. "Saint-Pierre, British pacifism and the quest for perpetual peace (1693–1748)." ''History of European Ideas'' 46.8 (2020): 1165–1182. * Vaïsse, Maurice. "A certain idea of peace in France from 1945 to the present day." ''French History'' 18.3 (2004): 331–337. * Wittner, Lawrence S. ''Rebels Against War: The American Peace Movement, 1933–1983'' (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984). * Ziemann, Benjamin. "German Pacifism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries." ''Neue Politische Literatur'' 2015.3 (2015): 415–43

online

Nonviolent Action Network – Nonviolent Action Network

Database of 300 nonviolent methods {{DEFAULTSORT:Peace Movement Peace movements, Anti-war movement Counterculture of the 1960s History of social movements Peace

A peace movement is a

A peace movement is a social movement

A social movement is either a loosely or carefully organized effort by a large group of people to achieve a particular goal, typically a Social issue, social or Political movement, political one. This may be to carry out a social change, or to re ...

which seeks to achieve ideals such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world peace. Some of the methods used to achieve these goals include advocacy of pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

, nonviolent resistance, diplomacy

Diplomacy is the communication by representatives of State (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, non-governmental institutions intended to influence events in the international syste ...

, boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

s, peace camps, ethical consumerism, supporting anti-war

An anti-war movement is a social movement in opposition to one or more nations' decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term ''anti-war'' can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conf ...

political candidates, supporting legislation to remove profits from government contracts to the military–industrial complex, banning guns, creating tools for open government and transparency, direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate directly decides on policy initiatives, without legislator, elected representatives as proxies, as opposed to the representative democracy m ...

, supporting whistleblower

Whistleblowing (also whistle-blowing or whistle blowing) is the activity of a person, often an employee, revealing information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe, unethical or ...

s who expose war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s or conspiracies to create wars, demonstrations, and political lobbying. The political cooperative is an example of an organization which seeks to merge all peace-movement and green organizations; they may have diverse goals, but have the common ideal of peace and humane sustainability. A concern of some peace activists is the challenge of attaining peace when those against peace often use violence as their means of communication and empowerment.

A global affiliation of activists and political interests viewed as having a shared purpose and constituting a single movement has been called "''the'' peace movement", or an all-encompassing "anti-war movement". Seen from this perspective, they are often indistinguishable and constitute a loose, responsive, event-driven collaboration between groups motivated by humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

, environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecolog ...

, veganism

Veganism is the practice of abstaining from the use of animal products and the consumption of animal source foods, and an associated philosophy that rejects the commodity status of animals. A person who practices veganism is known as a vega ...

, anti-racism

Anti-racism encompasses a range of ideas and political actions which are meant to counter racial prejudice, systemic racism, and the oppression of specific racial groups. Anti-racism is usually structured around conscious efforts and deliberate ...

, feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

, decentralization

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those related to planning and decision-making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group and gi ...

, hospitality

Hospitality is the relationship of a host towards a guest, wherein the host receives the guest with some amount of goodwill and welcome. This includes the reception and entertainment of guests, visitors, or strangers. Louis de Jaucourt, Louis, ...

, ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

, theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, and faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

.

The ideal of peace

Ideas differ about what "peace" is (or should be), which results in a number of movements seeking different ideals of peace. Although "anti-war" movements often have short-term goals, peace movements advocate an ongoing lifestyle and a proactive government policy. It is often unclear whether a movement, or a particular protest, is against war in general or against one's government's participation in a war. This lack of clarity (or long-term continuity) has been part of the strategy of those seeking to end a war, such as theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

.

Global protests against the U.S. invasion of Iraq in early 2003 are an example of a specific, short-term, loosely affiliated single-issue "movement" consisting of relatively-scattered ideological priorities ranging from pacifism to Islamism

Islamism is a range of religious and political ideological movements that believe that Islam should influence political systems. Its proponents believe Islam is innately political, and that Islam as a political system is superior to communism ...

and Anti-Americanism

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment and Americanophobia) is a term that can describe several sentiments and po ...

. Those involved in multiple, similar short-term movements develop trust relationships with other participants, and tend to join more-global, long-term movements.

Elements of the global peace movement seek to guarantee health security by ending war and ensure what they view as basic human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

, including the right of all people to have access to clean air, water, food, shelter and health care

Health care, or healthcare, is the improvement or maintenance of health via the preventive healthcare, prevention, diagnosis, therapy, treatment, wikt:amelioration, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other disability, physic ...

. Activists seek social justice in the form of equal protection and equal opportunity under the law for groups which had been disenfranchised.

The peace movement is characterized by the belief that humans should not wage war or engage in ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

about language, race, or natural resource

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest, and cultural value. ...

s, or engage in ethical conflict over religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

or ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

. Long-term opponents of war are characterized by the belief that military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

power does not equal justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

.

The peace movement opposes the proliferation of dangerous technology and weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a Biological agent, biological, chemical weapon, chemical, Radiological weapon, radiological, nuclear weapon, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill or significantly harm many people or cause great dam ...

, particularly nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s and biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or Pathogen, infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and Fungus, fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an ...

. Many adherents object to the export of weapons (including hand-held machine guns and grenade

A grenade is a small explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a Shell (projectile), shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A mod ...

s) by leading economic nations to developing countries. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) is an international institute based in Stockholm, Sweden. It was founded in 1966 and provides data, analysis and recommendations for armed conflict, military expenditure and arms trade a ...

has voiced a concern that artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the capability of computer, computational systems to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and decision-making. It is a field of re ...

, molecular engineering, genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

and proteomics

Proteomics is the large-scale study of proteins. Proteins are vital macromolecules of all living organisms, with many functions such as the formation of structural fibers of muscle tissue, enzymatic digestion of food, or synthesis and replicatio ...

have destructive potential. The peace movement intersects with Neo-Luddism and primitivism, and with mainstream critics such as Green parties, Greenpeace

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning network, founded in Canada in 1971 by a group of Environmental movement, environmental activists. Greenpeace states its goal is to "ensure the ability of the Earth to nurture life in all its biod ...

and the environmental movement

The environmental movement (sometimes referred to as the ecology movement) is a social movement that aims to protect the natural world from harmful environmental practices in order to create sustainable living. In its recognition of humanity a ...

.

These movements led to the formation of Green parties in a number of democratic countries in the late 20th century. The peace movement has influenced these parties in countries such as Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

.

History

Peace and Truce of God

The first mass peace movements were the Peace of God (, proclaimed in AD 989 at the Council of Charroux) and the Truce of God, which was proclaimed in 1027. The Peace of God was spearheaded by bishops as a response to increasing violence against monasteries after the fall of theCarolingian dynasty

The Carolingian dynasty ( ; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Franks, Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Pippinids, Arnulfi ...

. The movement was promoted at a number of subsequent church councils, including Charroux (989 and c. 1028), Narbonne (990), Limoges

Limoges ( , , ; , locally ) is a city and Communes of France, commune, and the prefecture of the Haute-Vienne Departments of France, department in west-central France. It was the administrative capital of the former Limousin region. Situated o ...

(994 and 1031), Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

(c. 1000), and Bourges

Bourges ( ; ; ''Borges'' in Berrichon) is a commune in central France on the river Yèvre (Cher), Yèvre. It is the capital of the Departments of France, department of Cher (department), Cher, and also was the capital city of the former provin ...

(1038). The Truce of God sought to restrain violence by limiting the number of days of the week and times of the year when the nobility was able to employ violence. These peace movements "set the foundations for modern European peace movements."

Peace churches

TheReformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

gave rise to a number of Protestant sects beginning in the 16th century, including the peace churches. Foremost among these churches were the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

), Amish

The Amish (, also or ; ; ), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, church fellowships with Swiss people, Swiss and Alsace, Alsatian origins. As they ...

, Mennonites

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

, and the Church of the Brethren

The Church of the Brethren is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition ( "Schwarzenau New Baptists") that was organized in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Schwarzenau, Germany during the Radical Pietist revival. ...

. The Quakers were prominent advocates of pacifism, who had repudiated all forms of violence and adopted a pacifist interpretation of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

as early as 1660. Throughout the 18th-century wars in which Britain participated, the Quakers maintained a principled commitment not to serve in an army or militia and not pay the alternative £10 fine.

18th century

The major 18th-century peace movements were products of two schools of thought which coalesced at the end of the century. One, rooted in the secularAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, promoted peace as the rational antidote to the world's ills; the other was part of the evangelical religious revival which had played an important role in the campaign for the abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

. Representatives of the former included Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

, in ''Extrait du Projet de Paix Perpetuelle de Monsieur l'Abbe Saint-Pierre'' (1756); Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

in ''Thoughts on Perpetual Peace'', and Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.

, who proposed the formation of a peace association in 1789. One representative of the latter was 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.

5 (five) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number, and cardinal number, following 4 and preceding 6, and is a prime number.

Humans, and many other animals, have 5 digits on their limbs.

Mathematics

5 is a Fermat pri ...

– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

; Wilberforce thought that by following the Christian ideals of peace and brotherhood, strict limits should be imposed on British involvement in the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

.

19th century

During theNapoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

(1793–1814), no formal peace movement was established in Britain until hostilities ended. A significant grassroots peace movement, animated by universalist ideals, emerged from the perception that Britain fought in a reactionary role and the increasingly visible impact of the war on the nation's welfare in the form of higher taxes and casualties. Sixteen peace petitions to Parliament were signed by members of the public; anti-war and anti- Pitt demonstrations were held, and peace literature was widely disseminated.

The first formal peace movements appeared in 1815 and 1816. The first movement in the United States was the New York Peace Society, founded in 1815 by theologian David Low Dodge

David Low Dodge (June 14, 1774April 23, 1852) was an American activist and theologian who helped to establish the New York Peace Society and was a founder of the New York Bible Society and the New York Tract Society. According to historian Dal ...

, followed by the Massachusetts Peace Society

The Massachusetts Peace Society (1815–1828) was an anti-war organization in Boston, Massachusetts, established to "diffuse light on the subject of war, and to cultivate the principles and spirit of peace." Founding officers included Thomas Dawes ...

. The groups merged into the American Peace Society

The American Peace Society was a pacifist group founded upon the initiative of William Ladd, in New York City, May 8, 1828. It was formed by the merging of many state and local societies, from New York, Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, ...

, which held weekly meetings and produced literature that was spread as far as Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

and Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

describing the horrors of war and advocating pacifism on Christian grounds. The London Peace Society

The Peace Society, International Peace Society or London Peace Society, originally known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was a British pacifist organisation that was active from 1816 until the 1930s.

History Fo ...

, also known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was formed by philanthropist William Allen in 1816 to promote permanent, universal peace. During the 1840s, British women formed 15-to-20 person "Olive Leaf Circles" to discuss and promote pacifist ideas.

The London Peace Society's influence began to grow during the mid-nineteenth century. Under Elihu Burritt

Elihu Burritt (December 8, 1810March 6, 1879) was an American diplomat, philanthropist, social activist, and blacksmith.Arthur Weinberg and Lila Shaffer Weinberg. ''Instead of Violence: Writings by the Great Advocates of Peace and Nonviolence Thr ...

and Henry Richard

Henry Richard (3 April 1812 – 20 August 1888) was a Congregational minister and Wales, Welsh Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament between 1868–1888. Richard was an advocate of peace and international arbitration, ...

, the society convened the first International Peace Congress

International Peace Congress, or International Congress of the Friends of Peace, was the name of a series of international meetings of representatives from peace societies from throughout the world held in various places in Europe from 1843 to 185 ...

in London in 1843. The congress decided on two goals: to achieve the ideal of peaceable arbitration

Arbitration is a formal method of dispute resolution involving a third party neutral who makes a binding decision. The third party neutral (the 'arbitrator', 'arbiter' or 'arbitral tribunal') renders the decision in the form of an 'arbitrati ...

of the affairs of nations, and to create an international institution to achieve it. Richard became the society's full-time secretary in 1850; he held the position for the next 40 years, and became known as the "Apostle of Peace". He helped secure one of the peace movement's earliest victories by securing a commitment for arbitration from the Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

in the Treaty of Paris (1856)

The Treaty of Paris of 1856, signed on 30 March 1856 at the Congress of Paris (1856), Congress of Paris, brought an end to the Crimean War (1853–1856) between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the United Kingdom of G ...

at the end of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. Wracked by social upheaval, the first peace congress on the European continent was held in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

in 1848; a second was held in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

a year later.

By the 1850s, these movements were becoming well organized in the major countries of Europe and North America, reaching middle-class activists beyond the range of the earlier religious connections.

Support decreased during the resurgence of militarism during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

and the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, the movement began to spread across Europe and infiltrate fledgling working-class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

movements. In 1870, Randal Cremer

Sir William Randal Cremer (18 March 1828 – 22 July 1908) usually known by his middle name "Randal", was a British Liberal Member of Parliament, a pacifist, and a leading advocate for international arbitration. He was awarded the Nobel Peace ...

formed the Workman's Peace Association in London. Cremer and the French economist Frédéric Passy

Frédéric Passy (20 May 182212 June 1912) was a French economist and pacifist who was a founding member of several peace societies and the Inter-Parliamentary Union. He was also an author and politician, sitting in the Chamber of Deputies fro ...

were the founding fathers of the Inter-Parliamentary Union

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU; , UIP) is an international organization of national parliaments. Its primary purpose is to promote democratic governance, accountability, and cooperation among its members; other initiatives include advancing g ...

, the first international organization for the arbitration of conflicts, in 1889. The National Peace Council

The National Peace Council (NPC), founded in 1908 and disbanded in 2000, acted as the co-ordinating body for almost 200 groups across Britain, with a membership ranging from small village peace groups to national trade unions and local authorities. ...

was founded after the 17th Universal Peace Congress in London in July and August 1908.

In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the novelist Baroness Bertha von Suttner

Baroness Bertha Sophie Felicitas von Suttner (; ; 9 June 184321 June 1914) was an Bohemian nobility, Austro-Bohemian noblewoman, Pacifism, pacifist and novelist. In 1905, she became the second female Nobel laureate (after Marie Curie in 1903), th ...

(1843–1914) after 1889 became a leading figure in the peace movement with the publication of her pacifist novel, ''Die Waffen nieder!

The book ''Die Waffen nieder!'' (''Down with Weapons!'') or ''Lay Down Your Arms!'' is the best-known novel by the author and peace activist Bertha von Suttner, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1905 for the book. The book was published in 1 ...

'' (''Lay Down Your Arms!''). The book was published in 37 editions and translated into 12 languages. She helped organize the German Peace Society

The German Peace Society ( (DFG)) was founded in 1892 in Berlin. In 1900 it moved its headquarters to Stuttgart. It still exists and is known as the ''Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft - Vereinigte KriegsdienstgegnerInnen'' (DFG-VK; German Peace Socie ...

and became known internationally as the editor of the international pacifist journal ''Die Waffen nieder!'' In 1905 she became the first woman to win a Nobel Peace Prize.

Mahatma Gandhi and nonviolent resistance

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

(1869–1948) was one of the 20th century's most influential spokesmen for peace and non-violence, and Gandhism

Gandhism is a body of ideas that describes the inspiration, vision, and the life work of Mohandas K. Gandhi. It is particularly associated with his contributions to the idea of nonviolent resistance, sometimes also called civil resistance.

The ...

is his body of ideas and principles Gandhi promoted. One of its most important concepts is nonviolent resistance. According to M. M. Sankhdher, Gandhism is not a systematic position in metaphysics or political philosophy but a political creed, an economic doctrine, a religious outlook, a moral precept, and a humanitarian worldview. An effort not to systematize wisdom but to transform society, it is based on faith in the goodness of human nature.

Gandhi was strongly influenced by the pacifism of Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

. Tolstoy wrote '' A Letter to a Hindu'' in 1908, which said that the Indian people could overthrow colonial rule only through passive resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, constr ...

. In 1909, Gandhi and Tolstoy began a correspondence about the practical and theological applications of nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. Gandhi saw himself as a disciple of Tolstoy because they agreed on the issues of opposition to state authority and colonialism, loathed violence, and preached non-resistance. However, they differed on political strategy. Gandhi called for political involvement; a nationalist, he was prepared to use nonviolent force but was also willing to compromise.

Gandhi was the first person to apply the principle of nonviolence on a large scale. The concepts of nonviolence (''ahimsa

(, IAST: , ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to actions towards all living beings. It is a key virtue in Indian religions like Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism.

(also spelled Ahinsa) is one of the cardinal vi ...

'') and nonresistance

Nonresistance (or non-resistance) is "the practice or principle of not resisting authority, even when it is unjustly exercised". At its core is discouragement of, even opposition to, physical resistance to an enemy. It is considered as a form of pr ...

have a long history in Indian religious and philosophical thought, and have had a number of revivals in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Jewish and Christian contexts. Gandhi explained his philosophy and way of life in his autobiography, ''The Story of My Experiments with Truth

''The Story of My Experiments with Truth'' (, , ) is the autobiography of Mahatma Gandhi, covering his life from early childhood through to 1921. It was written in weekly installments and published in his journal ''Navjivan'' from 1925 to 1929 ...

''. Some of his remarks were widely quoted, such as "There are many causes that I am prepared to die for, but no causes that I am prepared to kill for."

Gandhi later realized that a high level of nonviolence required great faith and courage, which not everyone possessed. He advised that everyone need not strictly adhere to nonviolence, especially if it was a cover for cowardice: "Where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence."

Gandhi came under political fire for his criticism of those who attempted to achieve independence through violence. He responded, "There was a time when people listened to me because I showed them how to give fight to the British without arms when they had no arms ... but today I am told that my non-violence can be of no avail against the Hindu–Moslem riots; therefore, people should arm themselves for self-defense."

Gandhi's views were criticized in Britain during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

. He told the British people in 1940, "I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions ... If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves man, woman, and child to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them."

World War I

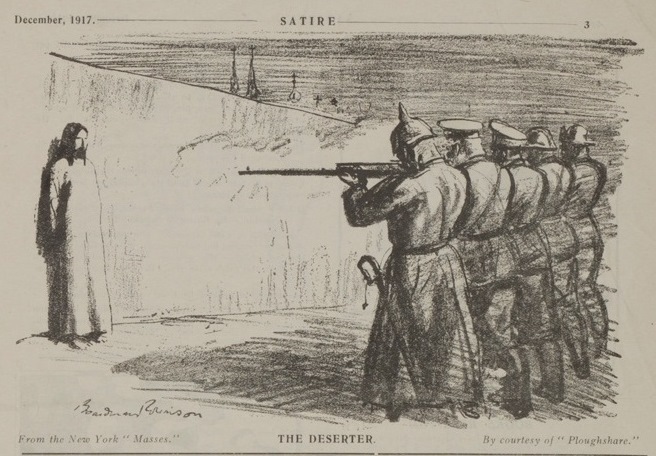

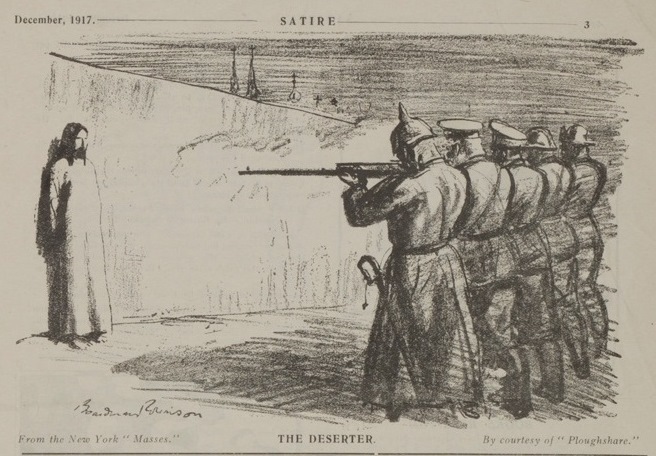

Although the onset of the

Although the onset of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

was generally greeted with enthusiastic patriotism across Europe, peace groups were active in condemning the war. Many socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

groups and movements were antimilitarist

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (especia ...

. They argued that by its nature, war was a type of governmental coercion of the working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

for the benefit of capitalist elites.

In 1915, the League of Nations Society

The League of Nations Society was a political group devoted to campaigning for an international organisation of nations, with the aim of preventing war.

The society was founded in 1915 by Baron Courtney and Willoughby Dickinson, both members of ...

was formed by British liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

leaders to promote a strong international organization which could enforce peaceful conflict resolution. Later that year, the League to Enforce Peace

The League to Enforce Peace was a non-state American organization established in 1915 to promote the formation of an international body for world peace. It was formed at Independence Hall in Philadelphia by American citizens concerned by the outbr ...

was established in the United States to promote similar goals. Hamilton Holt

Hamilton Holt (August 18, 1872 – April 26, 1951) was an American educator, editor, author and politician. He was President of Rollins College 1925 to 1949.

Biography

Holt was born on August 18, 1872, in Brooklyn, New York City, to George ...

published "The Way to Disarm: A Practical Proposal", an editorial in the ''Independent'' (his New York City weekly magazine) on September 28, 1914. The editorial called for an international organization to agree on the arbitration of disputes and guarantee the territorial integrity of its members by maintaining military forces sufficient to defeat those of any non-member. The ensuing debate among prominent internationalists modified Holt's plan to align it more closely with proposals in Great Britain put forth by Viscount James Bryce, a former ambassador from the U.K. to the U.S. These and other initiatives were pivotal to the attitude changes which gave rise to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

after the war. In addition to the peace churches, groups which protested against the war included the Woman's Peace Party

The Woman's Peace Party (WPP) was an American Pacifism, pacifist and First-wave feminism, feminist organization formally established in January 1915 in response to World War I. The organization is remembered as the first American peace organizatio ...

(organized in 1915 and led by Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

), the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) is a non-profit non-governmental organization working "to bring together women of different political views and philosophical and religious backgrounds determined to study and make kno ...

(ICWPP) (also organized in 1915), the American Union Against Militarism

The American Union Against Militarism (AUAM) was an American pacifist organization established in response to World War I. The organization attempted to keep the United States out of the European conflict through mass demonstrations, public lectu ...

, the Fellowship of Reconciliation

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). ...

, and the American Friends Service Committee

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Religious Society of Friends ('' Quaker)-founded'' organization working for peace and social justice in the United States and around the world. AFSC was founded in 1917 as a combined effort by ...

. Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 – May 18, 1973) was an American politician and women's rights advocate who became the first woman to hold federal office in the United States. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as ...

(the first woman elected to Congress) was another advocate of pacifism, and the only person to vote "no" on the U.S. entrance into both world wars.

Henry Ford

Peace promotion was a major activity of American automaker and philanthropistHenry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

(1863–1947). He set up a $1 million fund to promote peace, and published numerous antiwar articles and ads in hundreds of newspapers.

According to biographer Steven Watts, Ford's status as a leading industrialist gave him a worldview that warfare was wasteful folly that retarded long-term economic growth. The losing side in the war typically suffered heavy damage. Small business were especially hurt, for it takes years to recuperate. He argued in many newspaper articles that capitalism would discourage warfare because, "If every man who manufactures an article would make the very best he can in the very best way at the very lowest possible price the world would be kept out of war, for commercialists would not have to search for outside markets which the other fellow covets." Ford admitted that munitions makers enjoyed wars, but he argued the typical capitalist wanted to avoid wars to concentrate on manufacturing and selling what people wanted, hiring good workers, and generating steady long-term profits.

In late 1915, Ford sponsored and funded a Peace Ship

The Peace Ship was the common name for the ocean liner ''Oscar II'', on which American industrialist Henry Ford organized and launched his 1915 amateur peace mission to Europe; Ford chartered the ''Oscar II'' and invited prominent peace activists ...

to Europe, to help end the raging World War. He brought 170 peace activists; Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

was a key supporter who became too ill to join him. Ford talked to President Woodrow Wilson about the mission but had no government support. His group met with peace activists in neutral Sweden and the Netherlands. A target of much ridicule, Ford left the ship as soon as it reached Sweden.

Interwar period

Organizations

A popular slogan was "merchants of death

Merchants of death was an epithet used in the U.S. in the 1930s to attack industries and banks that had supplied and funded World War I (then called the Great War).

Origin

The term originated in 1932 as the title of an article in '' Le Crapouill ...

" alleging the promotion of war by armaments makers, based on a widely read nonfiction exposé ''Merchants of Death'' (1934), by H. C. Engelbrecht and F. C. Hanighen.

The immense loss of life during the First World War for what became known as futile reasons caused a sea-change in public attitudes to militarism. Organizations formed at this time included War Resisters' International

War Resisters' International (WRI), headquartered in London, is an international anti-war organisation with members and affiliates in over 40 countries.

History

''War Resisters' International'' was founded in Bilthoven, Netherlands in 1921 un ...

, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) is a non-profit non-governmental organization working "to bring together women of different political views and philosophical and religious backgrounds determined to study and make kno ...

, the No More War Movement The No More War Movement was the name of two pacifist organisations, one in the United Kingdom

and one in New Zealand.

British group

The British No More War Movement (NMWM) was founded in 1921 as a pacifist and socialist successor to the No-Consc ...

, and the Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

(PPU). The League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

convened several disarmament conferences, such as the Geneva Conference. They achieved very little. However the Washington conference of 1921–1922 did successfully limit naval armaments of the major powers during the 1920s.

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom helped convince the U.S. Senate to launch an influential investigation by the Nye Committee

The Nye Committee, officially known as the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, was a United States Senate committee (April 12, 1934 – February 24, 1936), chaired by U.S. Senator Gerald Nye (R-ND). The committee investi ...

to the effect that the munitions industry and Wall Street financiers had promoted American entry into World War I to cover their financial investments. The immediate result was a series of laws imposing neutrality on American business if other countries went to war.

Novels and films

Pacifism and revulsion to war were popular sentiments in 1920s Britain. A number of novels and poems about the futility of war and the slaughter of youth by old fools were published, including ''Death of a Hero

''Death of a Hero'' is a World War I novel by Richard Aldington. It was his first novel, published by Chatto & Windus in 1929, and thought to be partly autobiographical.

Plot summary

''Death of a Hero'' is the story of a young English arti ...

'' by Richard Aldington

Richard Aldington (born Edward Godfree Aldington; 8 July 1892 – 27 July 1962) was an English writer and poet. He was an early associate of the Imagist movement. His 50-year writing career covered poetry, novels, criticism and biography. He ed ...

, Erich Maria Remarque

Erich Maria Remarque (; ; born Erich Paul Remark; 22 June 1898 – 25 September 1970) was a German novelist. His landmark novel '' All Quiet on the Western Front'' (1928), based on his experience in the Imperial German Army during World War ...

's ''All Quiet on the Western Front

''All Quiet on the Western Front'' () is a semi-autobiographical novel by Erich Maria Remarque, a German veteran of World War I. The book describes the German soldiers' extreme physical and mental trauma during the war as well as the detachme ...

'' and Beverley Nichols

John Beverley Nichols (9 September 1898 – 15 September 1983) was an English writer, playwright and public speaker. He wrote more than 60 books and plays.

Career

Between his first book, the novel ''Prelude'' (1920), and his last, a book of po ...

' ''Cry Havoc!'' A 1933 University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

debate on the proposed motion that "one must fight for King and country" reflected the changed mood when the motion was defeated. Dick Sheppard established the Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

in 1934, renouncing war and aggression. The idea of collective security

Collective security is arrangement between states in which the institution accepts that an attack on one state is the concern of all and merits a collective response to threats by all. Collective security was a key principle underpinning the Lea ...

was also popular; instead of outright pacifism, the public generally exhibited a determination to stand up to aggression with economic sanctions and multilateral negotiations.

Spanish Civil War

TheSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

(1936–1939) was a major test of international pacifism, pacifist organizations (such as War Resisters' International and the Fellowship of Reconciliation

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). ...

), and individuals such as José Brocca

José Brocca (Professor José Brocca Ramón, 1891 – 1950) was a pacifist and humanitarian of the Spanish Civil War, who allied himself with the Republicans but sought nonviolent ways of resisting the Nationalist rebels.

His parents were Spanis ...

and Amparo Poch. Activists on the left often put their pacifism on pause in order to help the war effort of the Spanish government. Shortly after the war ended, Simone Weil

Simone Adolphine Weil ( ; ; 3 February 1909 – 24 August 1943) was a French philosopher, mystic and political activist. Despite her short life, her ideas concerning religion, spirituality, and politics have remained widely influential in cont ...

(despite volunteering for service on the Republican side) published ''The Iliad or the Poem of Force

"The Iliad, or The Poem of Force" () is a 24-page essay written in 1939 by Simone Weil.

The essay is about Homer's epic poem the ''Iliad'' and contains reflections on the conclusions one can draw from the epic regarding the nature of force in hu ...

'', which has been described as a pacifist manifesto. In response to the threat of fascism, pacifist thinkers such as Richard B. Gregg

Richard Bartlett Gregg (1885–1974) was an American Social philosophy, social philosopher said to be "the first American to develop a substantial theory of nonviolent resistance" based on the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, and so influenced the thin ...

devised plans for a campaign of nonviolent resistance in the event of a fascist invasion or takeover.

World War II

At the beginning ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, pacifist and anti-war sentiment declined in nations affected by the war. The communist-controlled American Peace Mobilization

The American Peace Mobilization (APM) was a peace group established in 1940 to oppose American aid to the Allies in World War II before the United States entered the war. It was officially cited in 1947 by United States Attorney General Tom C. Cl ...

reversed its anti-war activism, however, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. Although mainstream isolationist

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

groups such as the America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was an American isolationist pressure group against the United States' entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supporte ...

declined after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, a number of small religious and socialist groups continued their opposition to the war. Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

said that the necessity of defeating Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

and the Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

was a unique circumstance in which war was not the worst possible evil, and called his position "relative pacifism". Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

wrote, "I loathe all armies and any kind of violence, yet I'm firmly convinced that at present these hateful weapons offer the only effective protection." French pacifists André and Magda Trocmé helped to conceal hundreds of Jews fleeing the Nazis in the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (, literally "Le Chambon on Lignon"; ) is a commune in the Haute-Loire department in south-central France.

Residents have been primarily Huguenot or Protestant since the 17th century. During World War II these Huguenot ...

.'' Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed: The Story of Le Chambon and How Goodness Happened There'' Philip P. Hallie, (1979) New York: Harper & Row, After the war, the Trocmés were declared Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( ) is a title used by Yad Vashem to describe people who, for various reasons, made an effort to assist victims, mostly Jews, who were being persecuted and exterminated by Nazi Germany, Fascist Romania, Fascist Italy, ...

.

Pacifists in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

were treated harshly. German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky

Carl von Ossietzky (; 3 October 1889 – 4 May 1938) was a German journalist and Pacifism, pacifist. He was the recipient of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in exposing the clandestine German rearmament.

As editor-in-chief of the magazin ...

and Norwegian pacifist Olaf Kullmann

Olaf Bryn Kullmann (2 July 1892 – 9 July 1942) was a Norwegian naval officer and peace activist.

Early life and career

He was born in Stord in the county of Hordaland, Norway. He was a son of vicar and school manager Jakob Kullmann (1852–19 ...

(who remained active during the German occupation) died in concentration camps. Austrian farmer Franz Jägerstätter

Franz Jägerstätter, (also spelled Jaegerstaetter in English; born Franz Huber, 20 May 1907 – 9 August 1943) was an Austrians, Austrian farmer and conscientious objector during World War II. Jägerstätter was sentenced to death and executed ...

was executed in 1943 for refusing to serve in the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

.

Conscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

s and war tax resisters

Tax resistance is the refusal to pay tax because of opposition to the government that is imposing the tax, or to government policy, or as Taxation as theft, opposition to taxation in itself. Tax resistance is a form of direct action and, if in v ...

existed in both world wars, and the United States government allowed sincere objectors to serve in non-combat military roles. However, draft resisters who refused any cooperation with the war effort often spent much of each war in federal prisons. During World War II, pacifist leaders such as Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day, Oblate#Secular oblates, OblSB (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist and Anarchism, anarchist who, after a bohemianism, bohemian youth, became a Catholic Church, Catholic without aba ...

and Ammon Hennacy

Ammon Ashford Hennacy (July 24, 1893 – January 14, 1970) was an American Christian pacifist, anarchist, Wobbly, social activist, and member of the Catholic Worker Movement. He established the Joe Hill House of Hospitality in Salt Lake City ...

of the Catholic Worker Movement

The Catholic Worker Movement is a collection of autonomous communities founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in the United States in 1933. Its aim is to "live in accordance with the justice and charity of Jesus Christ". One of its guiding prin ...

urged young Americans not to enlist in the military. Peace movements have become widespread throughout the world since World War II, and their previously-radical beliefs are now a part of mainstream political discourse.

Anti-nuclear movement

Peace movements emerged in Japan, combining in 1954 to form the Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear-weapons tests was widespread, and an "estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".Jim Falk (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press, pp. 96–97. In the United Kingdom, theCampaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucl ...

(CND) held an inaugural public meeting at Central Hall Westminster

The Methodist Central Hall (also known as Central Hall Westminster) is a multi-purpose venue in the City of Westminster, London, serving primarily as a Methodist church and a conference centre. The building also houses an art gallery, a restaura ...

on 17 February 1958 which was attended by five thousand people. After the meeting, several hundred demonstrated at Downing Street

Downing Street is a gated street in City of Westminster, Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. In a cul-de-sac situated off Whiteh ...

.John Minnion and Philip Bolsover (eds.) ''The CND Story'', Allison and Busby

Allison & Busby (A & B) is a publishing house based in London established by Clive Allison and Margaret Busby in 1967. The company has built up a reputation as a leading independent publisher.

Background

Launching as a publishing company in May ...

, 1983,

The CND advocated the unconditional renunciation of the use, production, or dependence upon nuclear weapons by Britain, and the creation of a general disarmament convention. Although the country was progressing towards de-nuclearization, the CND declared that Britain should halt the flight of nuclear-armed planes, end nuclear testing, stop using missile bases, and not provide nuclear weapons to any other country.

The first Aldermaston March

The Aldermaston marches were anti-nuclear weapons demonstrations in the 1950s and 1960s, taking place on Easter weekend between the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, and London, over a distance of fifty- ...

, organized by the CND, was held on Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

1958. Several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster in Central London. It was established in the early-19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. Its name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar, the Royal Navy, ...

in London to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment

}

The Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) is a United Kingdom Ministry of Defence research facility responsible for the design, manufacture and support of warheads for the UK's nuclear weapons. It is the successor to the Atomic Weapons Researc ...

, near Aldermaston

Aldermaston ( ) is a village and civil parish in Berkshire, England. In the 2011 census, the parish had a population of 1,015. The village is in the Kennet Valley and bounds Hampshire to the south. It is approximately from Newbury, Basin ...

in Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons. The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s, when tens of thousands of people participated in the four-day marches. The CND tapped into the widespread popular fear of, and opposition to, nuclear weapons after the development of the first hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, anti-nuclear marches attracted large numbers of people.

Popular opposition to nuclear weapons produced a Labour Party resolution for unilateral nuclear disarmament at the 1960 party conference,April Carter, ''Direct Action and Liberal Democracy'', London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973, p. 64. but the resolution was overturned the following year and did not appear on later agendas. The experience disillusioned many anti-nuclear protesters who had previously put their hopes in the Labour Party.

Two years after the CND's formation, president Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

resigned to form the Committee of 100; the committee planned to conduct sit-down demonstrations in central London and at nuclear bases around the UK. Russell said that the demonstrations were necessary because the press had become indifferent to the CND and large-scale, direct action could force the government to change its policy. One hundred prominent people, many in the arts, attached their names to the organization. Large numbers of demonstrators were essential to their strategy but police violence, the arrest and imprisonment of demonstrators, and preemptive arrests for conspiracy diminished support. Although several prominent people took part in sit-down demonstrations (including Russell, whose imprisonment at age 89 was widely reported), many of the 100 signatories were inactive.

Since the Committee of 100 had a non-hierarchical structure and no formal membership, many local groups assumed the name. Although this helped civil disobedience to spread, it produced policy confusion; as the 1960s progressed, a number of Committee of 100 groups protested against social issues not directly related to war and peace.

In 1961, at the height of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace

Women Strike for Peace (WSP, also known as Women for Peace) was a women's peace activist group in the United States. Nearing the height of the Cold War in 1961, about 50,000 women marched in 60 cities around the United States to demonstrate again ...

marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the century's largest national women's peace protest.

In 1958, Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

and his wife presented the United Nations with a petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to nuclear weapons testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of Nuclear explosion, their explosion. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to si ...

. The 1961 Baby Tooth Survey, co-founded by Dr. Louise Reiss, indicated that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout

Nuclear fallout is residual radioactive material that is created by the reactions producing a nuclear explosion. It is initially present in the radioactive cloud created by the explosion, and "falls out" of the cloud as it is moved by the a ...

spread primarily via milk from cows which ate contaminated grass. Public pressure and the research results then led to a moratorium on above ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT), formally known as the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, prohibited all nuclear weapons testing, test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those co ...

signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, and Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

. On the day that the treaty went into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...