Paul W. Tibbets, Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the

In February 1942, Tibbets reported for duty with the 29th Bombardment Group as its engineering officer. Three weeks later he was named the commanding officer of the

In February 1942, Tibbets reported for duty with the 29th Bombardment Group as its engineering officer. Three weeks later he was named the commanding officer of the

Working with the Boeing plant in

Working with the Boeing plant in  Tibbets was promoted to colonel in January 1945 and brought his wife and family along with him to Wendover. He felt that allowing married men in the group to bring their families would improve morale, although it put a strain on his own marriage. In order to disguise all the civilian engineers on base who were working on the Manhattan Project, Tibbets was forced to lie to his wife; he told her that the engineers were "sanitary workers". At one point, Tibbets found that Lucy had co-opted a scientist to unplug a drain. During a meeting with these "sanitary engineers", Tibbets was told by

Tibbets was promoted to colonel in January 1945 and brought his wife and family along with him to Wendover. He felt that allowing married men in the group to bring their families would improve morale, although it put a strain on his own marriage. In order to disguise all the civilian engineers on base who were working on the Manhattan Project, Tibbets was forced to lie to his wife; he told her that the engineers were "sanitary workers". At one point, Tibbets found that Lucy had co-opted a scientist to unplug a drain. During a meeting with these "sanitary engineers", Tibbets was told by  On 5 August 1945, Tibbets formally named his B-29 ''

On 5 August 1945, Tibbets formally named his B-29 ''

After his retirement from the Air Force, Tibbets worked for

After his retirement from the Air Force, Tibbets worked for

:Tibbets, Paul W.

:Colonel (Air Corps), U.S. Army Air Forces

:393d Bombardment Squadron, 509th Composite Wing, Twentieth Air Force

:Date of Action: 6 August 1945

Citation:

:Tibbets, Paul W.

:Colonel (Air Corps), U.S. Army Air Forces

:393d Bombardment Squadron, 509th Composite Wing, Twentieth Air Force

:Date of Action: 6 August 1945

Citation:

509th Composite Group

Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima

BBC News item announcing Tibbets' death

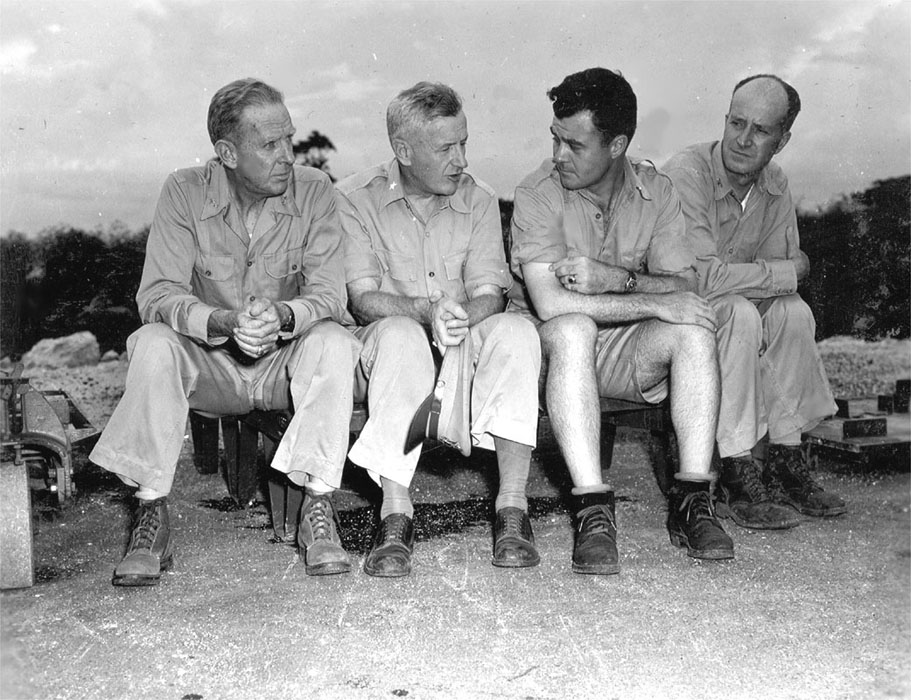

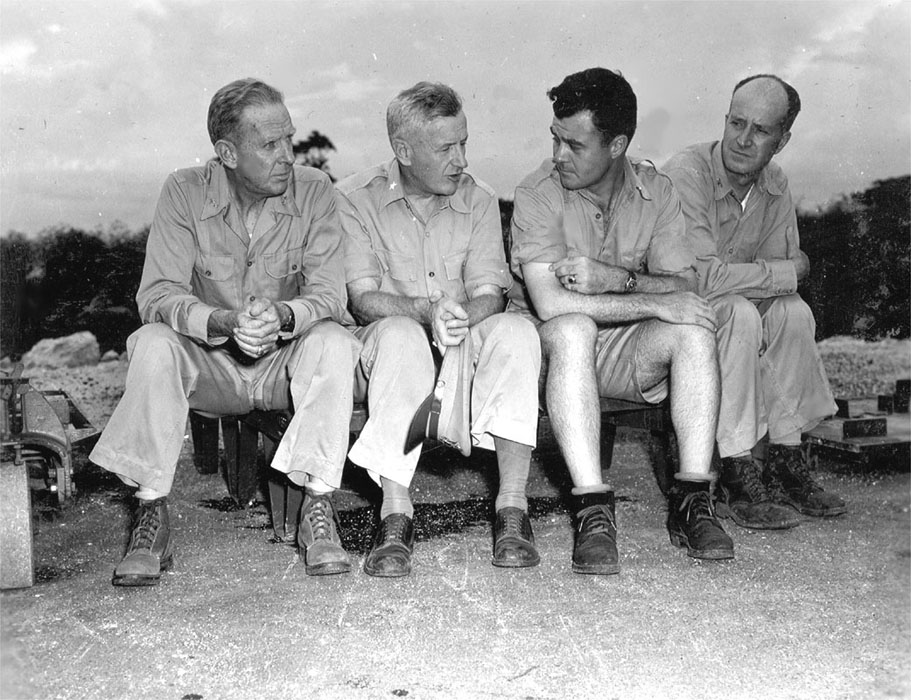

In pictures: Paul Tibbets

General Paul Tibbets: Reflections on Hiroshima

(Sep. 12, 1989 interview) - Voices of the Manhattan Project

A dramatic retelling of the Hiroshima mission with Paul Tibbets

Voices of the Manhattan Project

Nuclear War Radio Series

Voices of the Manhattan Project

Obituary, ''The Times'', 2 November 2007

* ttps://soundcloud.com/googleguy-2/paul-tibbets-interview-ann-blythe Paul Tibbets interviewed in 1982 by Ann Blythe {{DEFAULTSORT:Tibbets, Paul 1915 births 2007 deaths Recipients of the Air Medal Crew dropping the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki University of Florida alumni Amateur radio people United States Army Air Forces bomber pilots of World War II United States Army Air Forces officers United States Air Force generals American airline chief executives Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) People from Quincy, Illinois American expatriates in India Military personnel from Columbus, Ohio Military personnel from Illinois United States air attachés Burials at sea

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined Propeller (aeronautics), propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to ...

known as the ''Enola Gay

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel (United States), Colonel Paul Tibbets. On 6 August 1945, during the final stages of World War II, it became the Atomi ...

'' (named after his mother) when it dropped a Little Boy

Little Boy was a type of atomic bomb created by the Manhattan Project during World War II. The name is also often used to describe the specific bomb (L-11) used in the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ...

, the first of two atomic bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear explos ...

used in warfare, on the Japanese city of Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

.

Tibbets enlisted in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

in 1937 and qualified as a pilot in 1938. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, he flew anti-submarine patrols over the Atlantic. In February 1942, he became the commanding officer of the 340th Bombardment Squadron

34 may refer to:

* 34 (number)

* 34 BC

* AD 34

* 1934

* 2034

Science

* Selenium, a nonmetal in the periodic table

* 34 Circe, an asteroid in the asteroid belt

Music

* ''34'' (album), a 2015 album by Dre Murray

* "#34" (song), a 1994 song by ...

of the 97th Bombardment Group, which was equipped with the Boeing B-17

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is an American four-engined heavy bomber aircraft developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). A fast and high-flying bomber, the B-17 dropped more bombs than any other aircraft during ...

. In July 1942, the 97th became the first heavy bombardment group to be deployed as part of the Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Forces S ...

, and Tibbets became deputy group commander. He co-piloted the lead plane in the first American daylight heavy bomber

Heavy bombers are bomber Fixed-wing aircraft, aircraft capable of delivering the largest payload of air-to-ground weaponry (usually Aerial bomb, bombs) and longest range (aeronautics), range (takeoff to landing) of their era. Archetypal heavy ...

mission against German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly military occupation, militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the governmen ...

on 17 August 1942 that was piloted by Colonel Frank Alton Armstrong, Jr. (the 97th Bomb Group CO); and the first American raid of more than 100 bombers in Europe on 9 October 1942. Tibbets was chosen to fly Major General Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (1 May 1896 – 17 April 1984) was a United States Army officer who fought in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the U.S. Army during World War II.

During World War I, he wa ...

and Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

to Gibraltar. After flying 14 (possibly 25) combat missions, he became the assistant for bomber operations on the staff of the Twelfth Air Force

The Twelfth Air Force (12 AF; Air Forces Southern, (AFSOUTH)) is a Numbered Air Force of the United States Air Force Air Combat Command (ACC). It is headquartered at Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona.

The command is the air component to U ...

.

Tibbets returned to the United States in February 1943 to help with the development of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the Bo ...

. In September 1944, he was appointed the commander of the 509th Composite Group

The 509th Composite Group (509 CG) was a unit of the United States Army Air Forces created during World War II and tasked with the operational deployment of nuclear weapons. It conducted the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in ...

, which would conduct the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

. After the war, he participated in the Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity on July 16, 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices sinc ...

nuclear weapon tests at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese language, Marshallese: , , ), known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 19th century and 1946, is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. The atoll is at the no ...

in mid-1946, and was involved in the development of the Boeing B-47 Stratojet

The Boeing B-47 Stratojet (Boeing company designation Model 450) is a retired American long- range, six-engined, turbojet-powered strategic bomber designed to fly at high subsonic speed and at high altitude to avoid enemy interceptor aircraft ...

in the early 1950s. He commanded the 308th Bombardment Wing

The 308th Armament Systems Wing was a United States Air Force unit established in 1951, being activated and inactivated at different times in history. It was last assigned to the Air Armament Center, stationed at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. ...

and 6th Air Division

The 6th Air Division is an inactive United States Air Force unit. Its last assignment was with the Thirteenth Air Force, based at Clark Air Base, Philippines. It was inactivated on 15 December 1969.

Heraldry

On a shield per chevron argent and ...

in the late 1950s, and was military attaché

A military attaché or defence attaché (DA),Defence Attachés

''Geneva C ...

in India from 1964 to 1966. After leaving the Air Force in 1966, he worked for ''Geneva C ...

Executive Jet Aviation

NetJets Inc. is an American company that sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets.

Founded as Executive Jet Airways in 1964, it was later renamed Executive Jet Aviation. NetJets became the first private business jet charter ...

, serving on the founding board and as its president from 1976 until his retirement in 1987.

After the war he received wide publicity, including motion picture portrayals, and became a symbolic figure in the debate

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse, discussion, and oral addresses on a particular topic or collection of topics, often with a moderator and an audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for opposing viewpoints. Historica ...

over the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

Early life

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. was born inQuincy, Illinois

Quincy ( ) is a city in Adams County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. Located on the Mississippi River, the population was 39,463 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, down from 40,633 in 2010. The Quincy, Illinois, mic ...

, on 23 February 1915, the son of Paul Warfield Tibbets Sr. and his wife, Enola Gay Tibbets. When he was five years old, the family moved to Davenport, Iowa

Davenport ( ) is a city in Scott County, Iowa, United States, and its county seat. It is situated along the Mississippi River on the eastern border of the state. Davenport had a population of 101,724 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 cen ...

, and then to Iowa's capital, Des Moines

Des Moines is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Iowa, most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is the county seat of Polk County, Iowa, Polk County with parts extending into Warren County, Iowa, Wa ...

, where he was raised, and where his father became a confections wholesaler. When he was eight, his family moved to Hialeah, Florida

Hialeah ( ; ) is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. With a population of 223,109 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the sixth-largest city in Florida. It is the second largest city by population in Miami-Da ...

, to escape from harsh midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

ern winters. As a boy, he was very interested in flying. One day, his mother agreed to pay one dollar to get him into an airplane at the local carnival. In 1927, Tibbet's father hired a

barnstormer, Doug Davis, to fly over Hialeah Park Race Track

The Hialeah Park Race Track (also known as the Hialeah Race Track or Hialeah Park) is a historic racetrack in Hialeah, Florida. Its site covers 40 square blocks of central-east side Hialeah from Palm Avenue east to East 4th Avenue, and from East ...

as a promotional stunt. Tibbets, who was 12 years old at the time, flew with Davis, dropping Baby Ruth

Baby Ruth is an American candy bar made of peanuts, caramel, and milk chocolate-flavored nougat, covered in compound chocolate. Created in 1920, it is manufactured by the Ferrara Candy Company, a subsidiary of Ferrero.

History

In 1920, the C ...

candy bars with tiny parachutes to the crowd of people attending the races.

In the late 1920s, business issues forced Tibbets's family to return to Alton, Illinois

Alton ( ) is a city on the Mississippi River in Madison County, Illinois, United States, about north of St. Louis, Missouri. The population was 25,676 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is a part of the River Bend (Illinois), Riv ...

, where he graduated from Western Military Academy

Western Military Academy was a private military preparatory school located in Alton, Illinois, United States. It operated from 1879 to 1971. The campus is part of the National Register of Historic Places District (ID.78001167). The school motto wa ...

in 1933. He then attended the University of Florida

The University of Florida (Florida or UF) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Gainesville, Florida, United States. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida and a preem ...

in Gainesville, and became an initiated member of the Epsilon Zeta chapter of Sigma Nu

Sigma Nu () is an undergraduate Fraternities and sororities in North America, college fraternity founded at the Virginia Military Institute in 1869. Since its founding, Sigma Nu has chartered more than 279 chapters across the United States and Ca ...

fraternity

A fraternity (; whence, "wikt:brotherhood, brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club (organization), club or fraternal order traditionally of men but also women associated together for various religious or secular ...

in 1934. During that time, Tibbets took private flying lessons at Miami's Opa-locka Airport

Opa-locka () is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. Spanning roughly , it is part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 16,463, up from 15,219 in 2010.

Opa-locka was founded ...

with Rusty Heard, who later became a captain at Eastern Airlines

Eastern Air Lines (also colloquially known as Eastern) was a major airline in the United States that operated from 1926 to 1991. Before its dissolution, it was headquartered at Miami International Airport in an unincorporated area of Miami-Dade ...

. After his undergraduate work, Tibbets had planned on becoming an abdominal surgeon. He transferred to the University of Cincinnati

The University of Cincinnati (UC or Cincinnati, informally Cincy) is a public university, public research university in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. It was founded in 1819 and had an enrollment of over 53,000 students in 2024, making it the ...

after his second year to complete his pre-med

Pre-medical (often referred to as pre-med) is an educational track that undergraduate students mostly in the United States pursue prior to becoming medical students. It involves activities that prepare a student for medical school, such as pre-med ...

studies there, because the University of Florida had no medical school at the time. However, he attended for only a year and a half as he changed his mind about wanting to become a doctor. Instead, he decided to enlist in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and become a pilot in the United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical ri ...

.

Early military career

Because he went to a military school, attended some college, and had some flight experience, Tibbets qualified for the Aviation Cadet Training Program. On 25 February 1937, he enlisted in the army at Fort Thomas,Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, and was sent to Randolph Field

Randolph Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base located in Bexar County, Texas, ( east-northeast of Downtown San Antonio).

Opened in 1931, Randolph has been a flying training facility for the United States Army Air Corps, the United ...

in San Antonio

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for " Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the third-largest metropolitan area in Texas and the 24th-largest metropolitan area in the ...

, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, for primary and basic flight instruction. During his training, he showed himself to be an above-average pilot. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and received his pilot rating in 1938 at Kelly Field

Kelly Field (formerly Kelly Air Force Base) is a Joint-use airport, Joint-Use facility located in San Antonio, Texas. It was originally named after George E. M. Kelly, the first member of the U.S. military killed in the crash of an airplane he ...

in San Antonio.

After graduation, Tibbets was assigned to the 16th Observation Squadron

The 16th Electronic Warfare Squadron is an active United States Air Force unit. It is assigned to the 350th Spectrum Warfare Group at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. The squadron began as the 16th Aero Squadron and redesignated several times ove ...

, which was based at Lawson Field

Lawson may refer to:

Places Australia

* Lawson, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb of Canberra

* Lawson, New South Wales, a town in the Blue Mountains

Canada

* Lawson, Saskatchewan

* Lawson Island, Nunavut

United States

* Lawson, Arkansas ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, with a flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

supporting the Infantry School

A School of Infantry provides training in weapons and infantry tactics to infantrymen of a nation's military forces.

Schools of infantry include:

Australia

*Australian Army – School of Infantry, Lone Pine Barracks at Singleton, NSW.

Franc ...

at nearby Fort Benning

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

. It was at Fort Benning that Tibbets met Lucy Frances Wingate, then a clerk at a department store

A department store is a retail establishment offering a wide range of consumer goods in different areas of the store under one roof, each area ("department") specializing in a product category. In modern major cities, the department store mad ...

in Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, the capital city of the U.S. state of Ohio

* Columbus, Georgia, a city i ...

, Georgia. The two quietly married in a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

seminary in Holy Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, three ...

, Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, on 19 June 1938 even though Tibbets was a Protestant. Tibbets did not inform his family or his commanding officer, and the couple arranged for the notice to be kept out of the local newspaper. They had two sons. Paul III was born in 1940, in Columbus, Georgia, and graduated from Huntingdon College

Huntingdon College is a private Methodist college in Montgomery, Alabama. It was founded in 1854 as a women's college.

History

Huntingdon College was chartered on February 2, 1854, as " Tuskegee Female College" by the Alabama State Legislature a ...

and Auburn University

Auburn University (AU or Auburn) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Auburn, Alabama, United States. With more than 26,800 undergraduate students, over 6,100 post-graduate students, and a tota ...

. He was a colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

in the United States Army Reserve

The United States Army Reserve (USAR) is a Military reserve force, reserve force of the United States Army. Together, the Army Reserve and the Army National Guard constitute the Army element of the reserve components of the United States Armed ...

and worked as a hospital pharmacist

A pharmacist, also known as a chemist in English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English, is a healthcare professional who is knowledgeable about preparation, mechanism of action, clinical usage and legislation of medications in ...

. He died in West Monroe

West Monroe is the second largest city in Ouachita Parish, Louisiana, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, its population was 13,103. It is situated on the Ouachita River, across from the neighboring city of Monroe. The two cit ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, in 2016. The younger son, Gene Wingate Tibbets, was born in 1944, and was at the time of his death in 2012 residing in Georgiana

Georgiana is a Catalan, English, Greek and Romanian name. It is the feminine form of the male name George and a variation of the female names Georgina and Georgia. It comes from the Greek word (), meaning "farmer". A variant spelling is Georgi ...

in Butler County in southern Alabama.

While Tibbets was stationed at Fort Benning, he was promoted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

and served as a personal pilot for Brigadier General George S. Patton, Jr., in 1940 and 1941. In June 1941, Tibbets transferred to the 9th Bombardment Squadron of the 3d Bombardment Group

3D, 3-D, 3d, or Three D may refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics

* A three-dimensional space in mathematics Relating to three-dimensionality

* 3D computer graphics, computer graphics that use a three-dimensional representation of geome ...

at Hunter Field

Hunter Army Airfield , located in Savannah, Georgia, United States, is a military airfield and subordinate installation to Fort Stewart located in Hinesville, Georgia.

Hunter features a runway that is long and an Airport ramp, aircraft par ...

, Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

, Georgia, as the engineering officer, and flew the A-20 Havoc

The Douglas A-20 Havoc (company designation DB-7) is an American light bomber, attack aircraft, Intruder (air combat), night intruder, night fighter, and reconnaissance aircraft of World War II.

Designed to meet an Army Air Corps requirement for ...

. While there he was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

. In December 1941, he received orders to join the 29th Bombardment Group at MacDill Field

MacDill Air Force Base (MacDill AFB) is an active United States Air Force installation located 4 miles (6.4 km) south-southwest of downtown Tampa, Florida.

The "host wing" for MacDill AFB is the 6th Air Refueling Wing (6 ARW), assi ...

, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, for training on the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is an American four-engined heavy bomber aircraft developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). A fast and high-flying bomber, the B-17 dropped more bombs than any other aircraft during ...

. On 7 December 1941, Tibbets heard about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

while listening to the radio during a routine flight. Due to fears that German U-boats

U-boats are naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the First and Second World Wars. The term is an anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the German term refers to any submarine. Austro-Hungarian Na ...

might enter Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater i ...

and bombard MacDill Field, the 29th Bombardment Group moved to Savannah. Tibbets remained on temporary duty with the 3d Bombardment Group, forming an anti-submarine patrol at Pope Army Airfield

Pope Field is a U.S. military facility located northwest of the central business district of Fayetteville, in Spring Lake, Cumberland County, North Carolina, United States.. Federal Aviation Administration. effective 15 November 2012. Form ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, with 21 B-18 Bolo

The Douglas B-18 Bolo is an American twin-engined medium bomber which served with the United States Army Air Corps and the Royal Canadian Air Force (as the Digby) during the late 1930s and early 1940s. The Bolo was developed by the Douglas Airc ...

medium bombers. The B-18s were used as an intermediate trainer, which pilots flew after basic flight training in a Cessna UC-78

The Cessna AT-17 Bobcat or Cessna Crane is a twin-engine advanced trainer aircraft designed and made in the United States, and used during World War II to bridge the gap between single-engine trainers and larger multi-engine combat aircraft. The ...

and before qualifying in the B-17.

War against Germany

In February 1942, Tibbets reported for duty with the 29th Bombardment Group as its engineering officer. Three weeks later he was named the commanding officer of the

In February 1942, Tibbets reported for duty with the 29th Bombardment Group as its engineering officer. Three weeks later he was named the commanding officer of the 340th Bombardment Squadron

34 may refer to:

* 34 (number)

* 34 BC

* AD 34

* 1934

* 2034

Science

* Selenium, a nonmetal in the periodic table

* 34 Circe, an asteroid in the asteroid belt

Music

* ''34'' (album), a 2015 album by Dre Murray

* "#34" (song), a 1994 song by ...

of the 97th Bombardment Group, equipped with the B-17D. It was initially based at MacDill, and then Sarasota Army Airfield, Florida, before moving to Godfrey Army Airfield in Bangor, Maine

Bangor ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Penobscot County, Maine, United States. The city proper has a population of 31,753, making it the state's List of municipalities in Maine, third-most populous city, behind Portland, Maine, Portland ...

.

In July 1942 the 97th became the first heavy bombardment group of the Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Forces S ...

to be deployed to England, where it was based at RAF Polebrook

Royal Air Force Polebrook or more simply RAF Polebrook is a former Royal Air Force station located east-south-east of Oundle, at Polebrook, Northamptonshire, England. The airfield was built on Rothschild estate land starting in August 1940 ...

. It had been hastily assembled to meet demands for an early deployment, and arrived without any training in the basics of high altitude daylight bombing. In the first weeks of August 1942, under the tutelage of Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

veterans, the group received intensive training for its first mission. The group commander, Lieutenant Colonel Cornelius W. Cousland, was replaced by Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Frank A. Armstrong Jr.

Frank Alton Armstrong Jr. (May 24, 1902 – August 20, 1969) was a lieutenant general of the United States Air Force. As a brigadier general in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II, he was the inspiration for the main character i ...

, who appointed Tibbets as his deputy.

Tibbets co-piloted the lead bomber ''Butcher Shop'' with Armstrong as the pilot for the first American daylight heavy bomber mission on 17 August 1942, a shallow-penetration raid against a marshalling yard

A classification yard (American English, as well as the Canadian National Railway), marshalling yard (British, Hong Kong, Indian, and Australian English, and the former Canadian Pacific Railway) or shunting yard (Central Europe) is a railway y ...

in Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

in Occupied France

The Military Administration in France (; ) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called ' was established in June 19 ...

. This was not Tibbets's regular aircraft, ''Red Gremlin'', nor his regular crew, which did not included bombardier Thomas Ferebee

Thomas Wilson Ferebee (November 9, 1918 – March 16, 2000) was the bombardier aboard the B-29 Superfortress, '' Enola Gay'', which dropped the atomic bomb " Little Boy" on Hiroshima in 1945.

Biography

Thomas Wilson Ferebee was born on a ...

and navigator Theodore Van Kirk

Theodore Jerome "Dutch" Van Kirk (February 27, 1921 – July 28, 2014) was a navigator in the United States Army Air Forces, best known as the navigator of the ''Enola Gay'' when it dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Upon the death ...

, who later flew with him in ''Enola Gay''. On 9 October 1942, Tibbets led the first American raid of more than 100 bombers in Europe, attacking industrial targets in the French city of Lille

Lille (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city in the northern part of France, within French Flanders. Positioned along the Deûle river, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Prefectures in F ...

. Poor bombing accuracy resulted in numerous civilian casualties and less damage to the rail installations than hoped, but the mission was hailed an overall success because it reached its target against heavy and constant fighter attack. Of the 108 aircraft in the raid, 33 were shot down or had to turn back due to mechanical problems.

On that first mission, Tibbets saw in real time that his bombs were falling on innocent civilians. At the time, he thought to himself, "People are getting killed down there that don't have any business getting killed. Those are not soldiers". But then he thought back to a lesson he had learned during his time at medical school from his roommate who was a doctor. This doctor explained to him about his former classmates who failed the program and ended up in drug sales. The reason why they had failed the program was because "they had too much sympathy for their patients", which "destroyed their ability to render the medical necessities". It dawned on Tibbets that:

In the leadup to Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, the Allied invasion of North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, the commander of the Eighth Air Force, Major General Carl Spaatz

Carl Andrew Spaatz (born Spatz; 28 June 1891 – 14 July 1974), nicknamed "Tooey", was an American World War II general. As commander of Strategic Air Forces in Europe in 1944, he successfully pressed for the bombing of the enemy's oil productio ...

was ordered to provide his best two pilots for a secret mission. He chose Tibbets and Major Wayne Connors. Tibbets flew Major General Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (1 May 1896 – 17 April 1984) was a United States Army officer who fought in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the U.S. Army during World War II.

During World War I, he wa ...

from Polebrook

Polebrook is a village in Northamptonshire, England. The population (including Armston) at the 2011 census was 478.

History

There is evidence that Polebrook as a settlement dates back to 400 BC, where the village consisted of many farms. The fa ...

to Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

while Connors flew Clark's chief of staff, Brigadier General Lyman Lemnitzer

Lyman Louis Lemnitzer (29 August 1899 – 12 November 1988) was a United States Army General (United States), general who served as the fourth chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1960 to 1962. He then served as the Supreme Allied Commander ...

. A few weeks later Tibbets flew the Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Allies during World War I, and is currently used only within NATO for Supreme Allied Co ...

, Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, there. "By reputation", historian Stephen Ambrose

Stephen Edward Ambrose (January 10, 1936 – October 13, 2002) was an American historian, academic, and author, most noted for his books on World War II and his biographies of U.S. presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. He was a long ...

wrote, Tibbets was "the best flier in the Army Air Force".

Tibbets had flown seven (7) combat missions against targets in France (six) and Holland (one) when the 97th Bomb Group was transferred to North Africa as part of Major General Jimmy Doolittle

James Harold Doolittle (December 14, 1896 – September 27, 1993) was an American military general and aviation pioneer who received the Medal of Honor for his raid on Japan during World War II, known as the Doolittle Raid in his honor. He ma ...

's Twelfth Air Force

The Twelfth Air Force (12 AF; Air Forces Southern, (AFSOUTH)) is a Numbered Air Force of the United States Air Force Air Combat Command (ACC). It is headquartered at Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona.

The command is the air component to U ...

. For Tibbets, the war in North Africa introduced him to the realities of aerial warfare. He said that he saw the real effects of bombing civilians and the trauma of losing his brothers in arms. In January 1943, Tibbets, who had now flown 14 (possibly 25) combat missions, was assigned as the assistant for bomber operations to Colonel Lauris Norstad

Lauris Norstad (March 24, 1907 – September 12, 1988) was an American general officer in the United States Army and United States Air Force.

Early life and military career

Lauris Norstad was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota to Martin and Marie No ...

, Assistant Chief of Staff of Operations (A-3) of the Twelfth Air Force. Tibbets had recently been given a battlefield promotion to colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

, but did not receive it, as such promotions had to be confirmed by a panel of officers. He was told that Norstad had vetoed the promotion, saying "there's only going to be one colonel in operations".

Tibbets did not get along well with Norstad, or with Doolittle's chief of staff, Brigadier General Hoyt Vandenberg

Hoyt Sanford Vandenberg (January 24, 1899 – April 2, 1954) was a United States Air Force general. He served as the second Chief of Staff of the Air Force, and the second Director of Central Intelligence.

During World War II, Vandenberg was t ...

. In one planning meeting, Norstad wanted an all-out raid on Bizerte

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the List of northernmost items, northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under Fr ...

to be flown at . Tibbets protested that flak

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface ( submarine-launched), and air-bas ...

would be most effective at that altitude. When challenged by Norstad, Tibbets said he would lead the mission himself at 6,000 feet if Norstad would fly as his co-pilot. Norstad backed down, and the mission was successfully flown at .

War against Japan

WhenGeneral

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Henry H. "Hap" Arnold, the Chief of United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

, requested an experienced bombardment pilot to help with the development of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the Bo ...

bomber, Doolittle recommended Tibbets. Tibbets returned to the United States in February 1943. At the time, the B-29 program was beset by a host of technical problems, and the chief test pilot, Edmund T. Allen, had been killed in a crash of the prototype aircraft.

Working with the Boeing plant in

Working with the Boeing plant in Wichita, Kansas

Wichita ( ) is the List of cities in Kansas, most populous city in the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Sedgwick County, Kansas, Sedgwick County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 397, ...

, Tibbets test-flew the B-29 and soon accumulated more flight time in it than any other pilot. He found that without defensive armament and armor plating, the aircraft was lighter, and its performance was much improved. In simulated combat engagements against a P-47

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt is a World War II-era fighter aircraft produced by the American company Republic Aviation from 1941 through 1945. It was a successful high-altitude fighter, and it also served as the foremost American fighter-bombe ...

fighter at the B-29's cruising altitude of , he discovered that the B-29 had a smaller turning radius than the P-47, and could avoid it by turning away.

After a year of developmental testing of the B-29, Tibbets was assigned in March 1944 as director of operations of the 17th Bombardment Operational Training Wing (Very Heavy), a B-29 training unit based at Grand Island Army Air Field

Grand Island Army Airfield was a United States Army Air Forces airfield which operated from 1942 to 1946. After its closure, the base was reopened as Central Nebraska Regional Airport.

History

Grand Island Army Airfield was opened in 1942, a ...

, Nebraska, and commanded by Armstrong. Its role was to transition pilots to the B-29. Crews were reluctant to embrace the troublesome B-29, and to shame the male crews, Tibbets taught and certified

Certification is part of testing, inspection and certification and the provision by an independent body of written assurance (a certificate) that the product, service or system in question meets specific requirements. It is the formal attestatio ...

two Women Airforce Service Pilots

The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) (also Women's Army Service Pilots or Women's Auxiliary Service Pilots) was a civilian women pilots' organization, whose members were United States federal civil service employees. Members of WASP became t ...

, Dora Dougherty and Dorothea (Didi) Johnson Moorman, to fly the B-29 as demonstration pilots, and the crews' attitude changed.

On 1 September 1944, Tibbets reported to Colorado Springs Army Airfield, the headquarters of the Second Air Force

The Second Air Force (2 AF; ''2d Air Force'' in 1942) is a USAF numbered air force responsible for conducting basic military and technical training for Air Force enlisted members and non-flying officers. In World War II the CONUS unit defended ...

, where he met with its commander, Major General Uzal Ent

Uzal Girard Ent CBE (March 3, 1900 – March 5, 1948) was an American United States Army Air Forces, Army Air Forces officer who served as the commander of the Second Air Force during World War II.

Early life and education

Ent was born on ...

, and three representatives of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, Lieutenant Colonel John Lansdale Jr., Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

William S. Parsons, and Norman F. Ramsey Jr., who briefed him on the project. Tibbets was told that he would be in charge of the 509th Composite Group

The 509th Composite Group (509 CG) was a unit of the United States Army Air Forces created during World War II and tasked with the operational deployment of nuclear weapons. It conducted the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in ...

, a fully self-contained organization of about 1,800 men, which would have 15 B-29s and a high priority for all kinds of military stores. Ent gave Tibbets a choice of three possible bases: Great Bend Army Airfield, Kansas; Mountain Home Army Airfield, Idaho; or Wendover Army Air Field

Wendover Air Force Base is a former United States Air Force base in Utah now known as Wendover Airport. During World War II, it was a training base for B-17 and B-24 bomber crews. It was the training site of the 509th Composite Group, the B ...

, Utah. Tibbets selected Wendover for its remoteness.

When the operation was still in its development stages, Armstrong and Colonel Roscoe C. Wilson were the leading candidates to command the group who was designated to drop the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

. Wilson was the Army Air Force project officer who provided liaison support to the Manhattan Project. Armstrong was an experienced combat veteran against German targets, but he was in his forties and had been severely injured in a fire in the summer of 1943. Wilson had no combat experience and was qualified primarily because of his engineering background and association with the project. Tibbets was considerably younger than both men and had experience in both staff and command duties in heavy bomber combat operations. He was already an experienced B-29 pilot, which made him an ideal candidate for the top-secret project. Tibbets indicated that the decision on what aircraft to use to deliver the bomb was left to him.

Tibbets was promoted to colonel in January 1945 and brought his wife and family along with him to Wendover. He felt that allowing married men in the group to bring their families would improve morale, although it put a strain on his own marriage. In order to disguise all the civilian engineers on base who were working on the Manhattan Project, Tibbets was forced to lie to his wife; he told her that the engineers were "sanitary workers". At one point, Tibbets found that Lucy had co-opted a scientist to unplug a drain. During a meeting with these "sanitary engineers", Tibbets was told by

Tibbets was promoted to colonel in January 1945 and brought his wife and family along with him to Wendover. He felt that allowing married men in the group to bring their families would improve morale, although it put a strain on his own marriage. In order to disguise all the civilian engineers on base who were working on the Manhattan Project, Tibbets was forced to lie to his wife; he told her that the engineers were "sanitary workers". At one point, Tibbets found that Lucy had co-opted a scientist to unplug a drain. During a meeting with these "sanitary engineers", Tibbets was told by Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

that his aircraft might not survive the shock waves from an atomic bomb explosion.

On 6 March 1945 (concurrent with the activation of Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 1 ...

), the 1st Ordnance Squadron, Special (Aviation) was activated at Wendover, again using Army Air Forces personnel on hand or already at Los Alamos. Its purpose was to provide "skilled machinists, welders and munitions workers" and special equipment to the group to enable it to assemble atomic weapons at its operating base, thereby allowing the weapons to be transported more safely in their component parts. A rigorous candidate selection process was used to recruit personnel, reportedly with an 80% rejection rate. The 509th Composite Group reached full strength in May 1945.

With the addition of the 1st Ordnance Squadron to its roster in March 1945, the 509th Composite Group had an authorized strength of 225 officers and 1,542 enlisted men, almost all of whom deployed to Tinian

Tinian () is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the four constituent municipalities of the Northern ...

, an island in the northern Marianas

The Mariana Islands ( ; ), also simply the Marianas, are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly Volcano#Dormant and reactivated, dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean ...

within striking distance of Japan, in May and June 1945. The 320th Troop Carrier Squadron kept its base of operations at Wendover. In addition to its authorized strength, the 509th had attached to it on Tinian all 51 civilian and military personnel of Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 1 ...

. Furthermore, two representatives from Washington, D.C. were present on the island: the deputy director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General Thomas Farrell, and Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

William R. Purnell

Rear Admiral William Reynolds Purnell (6 September 1886 – 3 March 1955) was an officer in the United States Navy who served in World War I and World War II. A 1908 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, he captained destroyers during Wor ...

of the Military Policy Committee.

The ground support echelon of the 509th Composite Group received movement orders and moved by rail on 26 April 1945, to its port of embarkation at Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

, Washington. On 6 May the support elements sailed on the SS ''Cape Victory'' for the Marianas, while the group's materiel was shipped on the SS ''Emile Berliner''. An advance party of the air echelon flew by C-54 to North Field, Tinian, between 15 and 22 May, where it was joined by the ground echelon on 29 May 1945. Project Alberta's "Destination Team" also sent most of its members to Tinian to supervise the assembly, loading, and dropping of the bombs under the administrative title of 1st Technical Services Detachment, Miscellaneous War Department Group.

On 5 August 1945, Tibbets formally named his B-29 ''

On 5 August 1945, Tibbets formally named his B-29 ''Enola Gay

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel (United States), Colonel Paul Tibbets. On 6 August 1945, during the final stages of World War II, it became the Atomi ...

'' after his mother. ''Enola Gay'', serial number 4486292, had been personally selected by him, on recommendation of a civilian production supervisor, while it was still on the assembly line

An assembly line, often called ''progressive assembly'', is a manufacturing process where the unfinished product moves in a direct line from workstation to workstation, with parts added in sequence until the final product is completed. By mechan ...

at the Glenn L. Martin Company

The Glenn L. Martin Company, also known as The Martin Company from 1917 to 1961, was an American aircraft and aerospace industry, aerospace manufacturing company founded by aviation pioneer Glenn L. Martin. The Martin Company produced many impo ...

plant in Bellevue, Nebraska

Bellevue ( French for "beautiful view"; previously named Belleview) is a suburban city in Sarpy County, Nebraska, United States. It is part of the Omaha–Council Bluffs metropolitan area, and had a population of 64,176 as of the 2020 census, ...

. The regularly assigned aircraft commander, Robert A. Lewis

Robert Alvin Lewis (October 18, 1917 – June 18, 1983) was a United States Army Air Forces officer serving in the Pacific Theatre during World War II. He was the co-pilot and aircraft commander of the '' Enola Gay'', the B-29 Superfortress ...

, was unhappy to be displaced by Tibbets for this important mission, and became furious when he arrived at the airfield on the morning of 6 August to see the aircraft he considered his painted with the now-famous nose art. Lewis would fly the mission as Tibbets's co-pilot.

At 02:45 the next day—in accordance with the terms of Operations Order No. 35—the ''Enola Gay'' departed North Field for Hiroshima, Japan, with Tibbets at the controls. Tinian was approximately away from Japan, so it took six hours to reach Hiroshima. The atomic bomb, code-named "Little Boy

Little Boy was a type of atomic bomb created by the Manhattan Project during World War II. The name is also often used to describe the specific bomb (L-11) used in the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ...

", was dropped over Hiroshima at 08:15 local time. Tibbets recalled that the city was covered with a tall mushroom cloud

A mushroom cloud is a distinctive mushroom-shaped flammagenitus cloud of debris, smoke, and usually condensed water vapour resulting from a large explosion. The effect is most commonly associated with a nuclear explosion, but any sufficiently e ...

after the bomb was dropped.

Tibbets was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

by Spaatz immediately after landing on Tinian. He became a celebrity, with pictures and interviews of his wife and children in the major American newspapers. He was seen as a national hero who had ended the war with Japan. Tibbets later received an invitation from President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

to visit the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

. The 509th Composite Group was awarded an Air Force Outstanding Unit Award

The Air and Space Outstanding Unit Award (ASOUA) is one of the unit awards of the United States Air Force and United States Space Force. It was established in 1954 as the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award and was the first independent Air Force ...

in 1999.

Post-war military career

The 509th Composite Group returned to the United States on 6 November 1945, and was stationed at Roswell Army Airfield, New Mexico. Colonel William H. Blanchard replaced Tibbets as group commander on 22 January 1946, and also became the first commander of the509th Bombardment Wing

The 509th Bomb Wing (509 BW) is a United States Air Force unit assigned to the Air Force Global Strike Command, Eighth Air Force. It is stationed at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri.

The 509 BW is the host unit at Whiteman, and operates th ...

, the successor to the 509th Composite Group. Tibbets was a technical advisor to the 1946 Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity on July 16, 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices sinc ...

nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese language, Marshallese: , , ), known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 19th century and 1946, is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. The atoll is at the no ...

in the Pacific, but he and his ''Enola Gay'' crew were not chosen to drop another atomic bomb.

Tibbets then attended the Air Command and Staff School

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosphere ...

at Maxwell Air Force Base

Maxwell Air Force Base , officially known as Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base, is a United States Air Force (USAF) installation under the Air Education and Training Command (AETC). The installation is located in Montgomery, Alabama, United States. ...

, Alabama. On graduating in 1947 he was posted to the Directorate of Requirements at Air Force Headquarters at the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The building was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As ...

. When the head of the directorate, Brigadier General Thomas S. Power, was posted to London as air attaché, he was replaced by Brigadier General Carl Brandt. Brandt appointed Tibbets as director of Directorate of Requirements's Strategic Air Division, which was responsible for drawing up requirements for future bombers. Tibbets was convinced that the bombers of the future would be jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by one or more jet engines.

Whereas the engines in Propeller (aircraft), propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much ...

and thus became involved in the Boeing B-47 Stratojet

The Boeing B-47 Stratojet (Boeing company designation Model 450) is a retired American long- range, six-engined, turbojet-powered strategic bomber designed to fly at high subsonic speed and at high altitude to avoid enemy interceptor aircraft ...

program. He subsequently served as B-47 project officer at Boeing in Wichita from July 1950 until February 1952. He then became commander of the Proof Test Division at Eglin Air Force Base

Eglin Air Force Base is a United States Air Force (USAF) base in the western Florida panhandle, located about southwest of Valparaiso, Florida, Valparaiso in Okaloosa County, Florida, Okaloosa County.

The host unit at Eglin is the 96th Test ...

in Valparaiso, Florida

Valparaiso is a city in Okaloosa County, Florida, Okaloosa County, Florida, United States. It is part of the Crestview, Florida, Crestview–Destin, Florida, Fort Walton Beach–Destin, Florida Fort Walton Beach-Crestview-Destin, Florida ...

, where flight testing of the B-47 was conducted.

Tibbets returned to Maxwell Air Force Base, where he attended the Air War College

The Air War College (AWC) is the senior Professional Military Education (PME) school of the U.S. Air Force. A part of the United States Air Force's Air University (United States Air Force), Air University, AWC emphasizes the employment of air, ...

. After he graduated in June 1955, he became Director of War Plans at the Allied Air Forces in Central Europe Headquarters at Fontainebleau, France

Fontainebleau ( , , ) is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the ''arrondissem ...

. He left Lucy and his sons behind in Alabama, and he and Lucy divorced that year. During his posting to France, he met a French divorcee named Andrea Quattrehomme, who became his second wife. He returned to the United States in February 1956 to command the 308th Bombardment Wing

The 308th Armament Systems Wing was a United States Air Force unit established in 1951, being activated and inactivated at different times in history. It was last assigned to the Air Armament Center, stationed at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. ...

at Hunter Air Force Base, Georgia, and married her in the base chapel on 4 May 1956. They had a son, James Tibbets.

In January 1958, Tibbets became commander of the 6th Air Division

The 6th Air Division is an inactive United States Air Force unit. Its last assignment was with the Thirteenth Air Force, based at Clark Air Base, Philippines. It was inactivated on 15 December 1969.

Heraldry

On a shield per chevron argent and ...

at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. and was promoted to brigadier general in 1959. This was followed by another tour of duty at the Pentagon as director of Management Analysis. In July 1962, he was assigned to the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

as deputy director for operations, and then, in June 1963, as deputy director for the National Military Command System. In 1964, Tibbets was named military attaché

A military attaché or defence attaché (DA),Defence Attachés

''Geneva C ...

in India. He spent 22 months there on this posting, which ended in June 1966. He retired from the ''Geneva C ...

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

(USAF) on 31 August 1966.

Later life and death

After his retirement from the Air Force, Tibbets worked for

After his retirement from the Air Force, Tibbets worked for Executive Jet Aviation

NetJets Inc. is an American company that sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets.

Founded as Executive Jet Airways in 1964, it was later renamed Executive Jet Aviation. NetJets became the first private business jet charter ...

(EJA), an air taxi company based in Columbus, Ohio

Columbus (, ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Ohio, most populous city of the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 United States census, 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the List of United States ...

, and now called NetJets

NetJets Inc. is an American company that sells Fractional ownership of aircraft, fractional ownership shares in private business jets.

Founded as Executive Jet Airways in 1964, it was later renamed Executive Jet Aviation. NetJets became the ...

. He was one of the founding board members and attempted to extend the company's operations to Europe, but was unsuccessful. He retired from the company in 1968, and returned to Miami, Florida, where he had spent part of his childhood. The banks foreclosed on EJA in 1970, and Bruce Sundlun

Bruce George Sundlun (January 19, 1920 – July 21, 2011) was an American businessman, politician and member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party who served as List of governors of Rhode Island, 71st governor of Rhode Island ...

became president. Sundlun lured Tibbets back to EJA that year. Tibbets succeeded Sundlun as president on 21 April 1976, and remained in the role until 1986. He served for a year as a consultant before his second and final retirement from EJA in 1987.

Tibbets died in his Columbus, Ohio, home on 1 November 2007, at the age of 92. He had suffered small stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

s and heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome caused by an impairment in the heart's ability to Cardiac cycle, fill with and pump blood.

Although symptoms vary based on which side of the heart is affected, HF ...

during his final years and had been in hospice

Hospice care is a type of health care that focuses on the palliation of a terminally ill patient's pain and symptoms and attending to their emotional and spiritual needs at the end of life. Hospice care prioritizes comfort and quality of life b ...

care. He was survived by his French-born wife, Andrea, and two sons from his first marriage, Paul III and Gene as well as his son, James, from his second marriage. Tibbets had asked for no funeral or headstone, because he feared that opponents of the bombing might use it as a place of protest or destruction. In accordance with his wishes, his body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered over the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

; he had flown over the Channel many times during the war.

Tibbets' grandson Paul W. Tibbets IV graduated from the United States Air Force Academy

The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) is a United States service academies, United States service academy in Air Force Academy, Colorado, Air Force Academy Colorado, immediately north of Colorado Springs, Colorado, Colorado Springs. I ...

in 1989, and in April 2006 became commander of the 393rd Bomb Squadron, flying the B-2 Spirit

The Northrop B-2 Spirit, also known as the Stealth Bomber, is an American Heavy bomber, heavy strategic bomber, featuring low-observable stealth aircraft, stealth technology designed to penetrator (aircraft), penetrate dense anti-aircraft war ...

at Whiteman AFB

Whiteman Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base located just south of Knob Noster, Missouri, United States. The base is the current home of the B-2 Spirit bomber. It is named for 2nd Lt George Whiteman, who was killed during the atta ...

, Missouri. The squadron was one of the two operational squadrons that had formed part of the 509th Composite Group when Tibbets commanded it. Paul Tibbets IV was promoted to brigadier general in 2014, and became Deputy Director for Nuclear Operations at the Global Operations Directorate of the United States Strategic Command

The United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) is one of the eleven unified combatant commands in the United States Department of Defense. Headquartered at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, USSTRATCOM is responsible for Strategic_nuclear_weap ...

at Offutt Air Force Base

Offutt Air Force Base is a U.S. Air Force base south of Omaha, adjacent to Bellevue in Sarpy County, Nebraska. It is the headquarters of the U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), the 557th Weather Wing, and the 55th Wing (55 WG) of the ...

in Nebraska. As such, he was responsible for America's strategic nuclear forces. On 5 June 2015, he assumed command of the 509th Bomb Wing

The 509th Bomb Wing (509 BW) is a United States Air Force unit assigned to the Air Force Global Strike Command, Eighth Air Force. It is stationed at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri.

The 509 BW is the host unit at Whiteman, and operates t ...

.

Legacy

In later life, Tibbets strongly defended the decision to use the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and became a symbolic figure in the debate over their use. At the time of his posting to India, a newspaper denounced him as the "world's greatest killer". In a 1975 interview he said: "I'm proud that I was able to start with nothing, plan it and have it work as perfectly as it did ... I sleep clearly every night". "I knew when I got the assignment", he told a reporter in 2005, "it was going to be an emotional thing. We had feelings, but we had to put them in the background. We knew it was going to kill people right and left. But my one driving interest was to do the best job I could so that we could end the killing as quickly as possible". In 1976, the United States government apologized to Japan after Tibbets re-enacted the bombing—complete with a mushroom cloud—in a restored B-29 at anair show

An air show (or airshow, air fair, air tattoo) is a public event where aircraft are trade fair, exhibited. They often include aerobatics demonstrations, without which they are called "static air shows" with aircraft parked on the ground.

The ...

in Texas. He said that he had not intended for the re-enactment to insult the Japanese people. In 1995, he denounced the 50th-anniversary exhibition of the ''Enola Gay'' at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

, which attempted to present the bombing in context with the destruction it caused, as a "damn big insult", due to its focus on the Japanese casualties rather than the brutality of the Japanese government. He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame

The National Aviation Hall of Fame (NAHF) is a museum, annual awards ceremony and learning and research center that was founded in 1962 as an Ohio non-profit corporation in Dayton, Ohio, United States, known as the "Birthplace of Aviation" with ...

in 1996.

Awards and decorations

Source: Ohio History Central.Distinguished Service Cross citation

:Tibbets, Paul W.

:Colonel (Air Corps), U.S. Army Air Forces

:393d Bombardment Squadron, 509th Composite Wing, Twentieth Air Force

:Date of Action: 6 August 1945

Citation:

:Tibbets, Paul W.

:Colonel (Air Corps), U.S. Army Air Forces

:393d Bombardment Squadron, 509th Composite Wing, Twentieth Air Force

:Date of Action: 6 August 1945

Citation:

In popular culture

Barry Nelson played Tibbets in the film ''The Beginning or the End

''The Beginning or the End'' is a 1947 American docudrama film about the development of the atomic bomb in World War II, directed by Norman Taurog, starring Brian Donlevy, Robert Walker, and Tom Drake, and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Th ...

'' (1947). '' Above and Beyond'' (1952) depicted the World War II events that involved Tibbets; Robert Taylor starred as Tibbets and Eleanor Parker

Eleanor Jean Parker (June 26, 1922 – December 9, 2013) was an American actress. She was nominated for three Academy Awards for her roles in the films ''Caged (1950 film), Caged'' (1950), ''Detective Story (1951 film), Detective Story'' (1951 ...

played the role of his first wife Lucy. Tibbets was also the model for screenwriter Sy Bartlett

Sidney Bartlett (July 10, 1900 – May 29, 1978, born Sacha Baraniev) was a Ukrainian-American author and screenwriter and producer of Hollywood films.

Early life

Sy Bartlett was born Sacha Baraniev on July 10, 1900, in the Black Sea seaport o ...

's fictional character "Major Joe Cobb" in the film ''Twelve O'Clock High

''Twelve O'Clock High'' is a 1949 American war film directed by Henry King and based on the novel of the same name by Sy Bartlett and Beirne Lay Jr. It stars Gregory Peck as Brig. General Frank Savage. Hugh Marlowe, Gary Merrill, Millard ...