Paul Reeves on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Paul Alfred Reeves (6 December 1932 – 14 August 2011) was a New Zealand clergyman who served as the 15th

(p. 96) He was Bishop of Auckland from 1979 to 1985, and additionally as Archbishop and Primate of New Zealand, the leader of New Zealand's Anglicans, from 1980 to 1985. During this time Reeves also served as chairman of the Environmental Council (1974–76), and he served as president of the National Council of Churches in New Zealand (1984–85). Reeves was a supporter of

Biography at Holy Trinity Cathedral website

* ttp://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/ideas/20110508 Radio NZ interview, 8 May 2011Sir Paul talks extensively about his life and work with interviewer Chris Laidlaw. (Listen directly or download options) {{DEFAULTSORT:Reeves, Paul Alfred 1932 births 2011 deaths Alumni of St Peter's College, Oxford Primates of New Zealand Anglican bishops of Auckland Anglican bishops of Waiapu Honorary Fellows of St Peter's College, Oxford People educated at Wellington College, Wellington Governors-general of New Zealand Knights of Justice of the Order of St John New Zealand republicans 20th-century Anglican archbishops in New Zealand Victoria University of Wellington alumni New Zealand Māori religious leaders Te Āti Awa people Members of the Order of New Zealand New Zealand Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George New Zealand Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Companions of the Queen's Service Order Companions of the Order of Fiji New Zealand Knights Bachelor Academics of the University of Edinburgh

governor-general of New Zealand

The governor-general of New Zealand () is the representative of the monarch of New Zealand, currently King Charles III. As the King is concurrently the monarch of 14 other Commonwealth realms and lives in the United Kingdom, he, on the Advice ...

from 1985 to 1990 and as Archbishop and Primate of New Zealand from 1980 to 1985. He was the first governor-general of Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

descent. He also served as the third Chancellor of Auckland University of Technology

Auckland University of Technology ( AUT; ) is a university in New Zealand, formed on 1 January 2000 when a former technical college (originally established in 1895) was granted university status. AUT is New Zealand's third largest university i ...

, from 2005 until his death.

Early life and education

Reeves was born inWellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

, New Zealand, on 6 December 1932, the son of D'arcy Reeves by his marriage to Hilda Pirihira, who had moved from Waikawa to Newtown, a working-class suburb of Wellington. Hilda was of Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

descent, of the Te Āti Awa

Te Āti Awa or Te Ātiawa is a Māori iwi with traditional bases in the Taranaki and Wellington regions of New Zealand. Approximately 17,000 people registered their affiliation to Te Āti Awa in 2001, with about 10,000 in Taranaki, 2,000 in We ...

iwi

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori, roughly means or , and is often translated as "tribe". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, and is typically pluralised as such in English.

...

; D'arcy was Pākehā

''Pākehā'' (or ''Pakeha''; ; ) is a Māori language, Māori-language word used in English, particularly in New Zealand. It generally means a non-Polynesians, Polynesian New Zealanders, New Zealander or more specifically a European New Zeala ...

and worked for the tramways.

Reeves was educated at Wellington College and at Victoria College, University of New Zealand (now the Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington (), also known by its shorter names "VUW" or "Vic", is a public university, public research university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of New Zealand Parliament, Parliament, and w ...

), where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

in 1955 and a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

in 1956. He went on to study for ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

as an Anglican priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

at St John's College, Auckland, receiving his Licentiate in Theology in 1958.

Religious ministry

Deacon and priest

Reeves was ordaineddeacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions.

Major Christian denominations, such as the Cathol ...

in 1958. After serving a brief curacy

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are ass ...

at Tokoroa

Tokoroa is the fourth-largest town in the Waikato region of the North Island of New Zealand and largest settlement in the South Waikato District. Located 30 km southwest of Rotorua and 20 km south of Putāruru, close to the foot of th ...

, he spent the period 1959–64 in England. From 1959 until 1961 he was an Advanced Student at St Peter's College, Oxford

St Peter's College is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford. Located on New Inn Hall Street, Oxford, United Kingdom, it occupies the site of two of the university's academic halls of the Univers ...

(Bachelor of Arts 1961, Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

1965) as well as Assistant Curate at the University Church of St Mary the Virgin

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin (St Mary's or SMV for short) is an Anglican church in Oxford situated on the north side of the High Street. It is the centre from which the University of Oxford grew and its parish consists almost excl ...

. He was ordained priest in 1960. He served two further curacies in England, first at Kirkley St Peter (1961–63), then at Lewisham St Mary (1963–64).

Returning to New Zealand, Reeves was Vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English p ...

of Okato St Paul (1964–66), Lecturer in Church History at St John's College, Auckland (1966–69), and Director of Christian Education for the Anglican Diocese of Auckland

The Diocese of Auckland is one of the thirteen dioceses and ''hui amorangi'' ( Māori bishoprics) of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia. The Diocese covers the area stretching from North Cape down to the Waikato River, ac ...

(1969–71).

Bishop, archbishop, and primate

In 1971 Reeves was appointedBishop of Waiapu

The Diocese of Waiapu is one of the 13 dioceses and ''hui amorangi'' (Māori bishoprics) of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia. The Diocese covers the area around the East Coast of the North Island of New Zealand, includin ...

and consecrated to the episcopate

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

on 25 March.ACANZP Lectionary, 2009(p. 96) He was Bishop of Auckland from 1979 to 1985, and additionally as Archbishop and Primate of New Zealand, the leader of New Zealand's Anglicans, from 1980 to 1985. During this time Reeves also served as chairman of the Environmental Council (1974–76), and he served as president of the National Council of Churches in New Zealand (1984–85). Reeves was a supporter of

Citizens for Rowling

The Citizens for Rowling campaign was a failed campaign to stop Robert Muldoon winning the 1975 New Zealand election. It was named after then Labour Prime Minister Bill Rowling in the lead-up to the 1975 general election. Members of the campa ...

(the campaign for the re-election of Labour Prime Minister Bill Rowling

Sir Wallace Edward Rowling (; 15 November 1927 – 31 October 1995), commonly known as Bill Rowling, was a New Zealand politician who was the 30th prime minister of New Zealand from 1974 to 1975. He held office as the Leader of the New Zealand ...

).

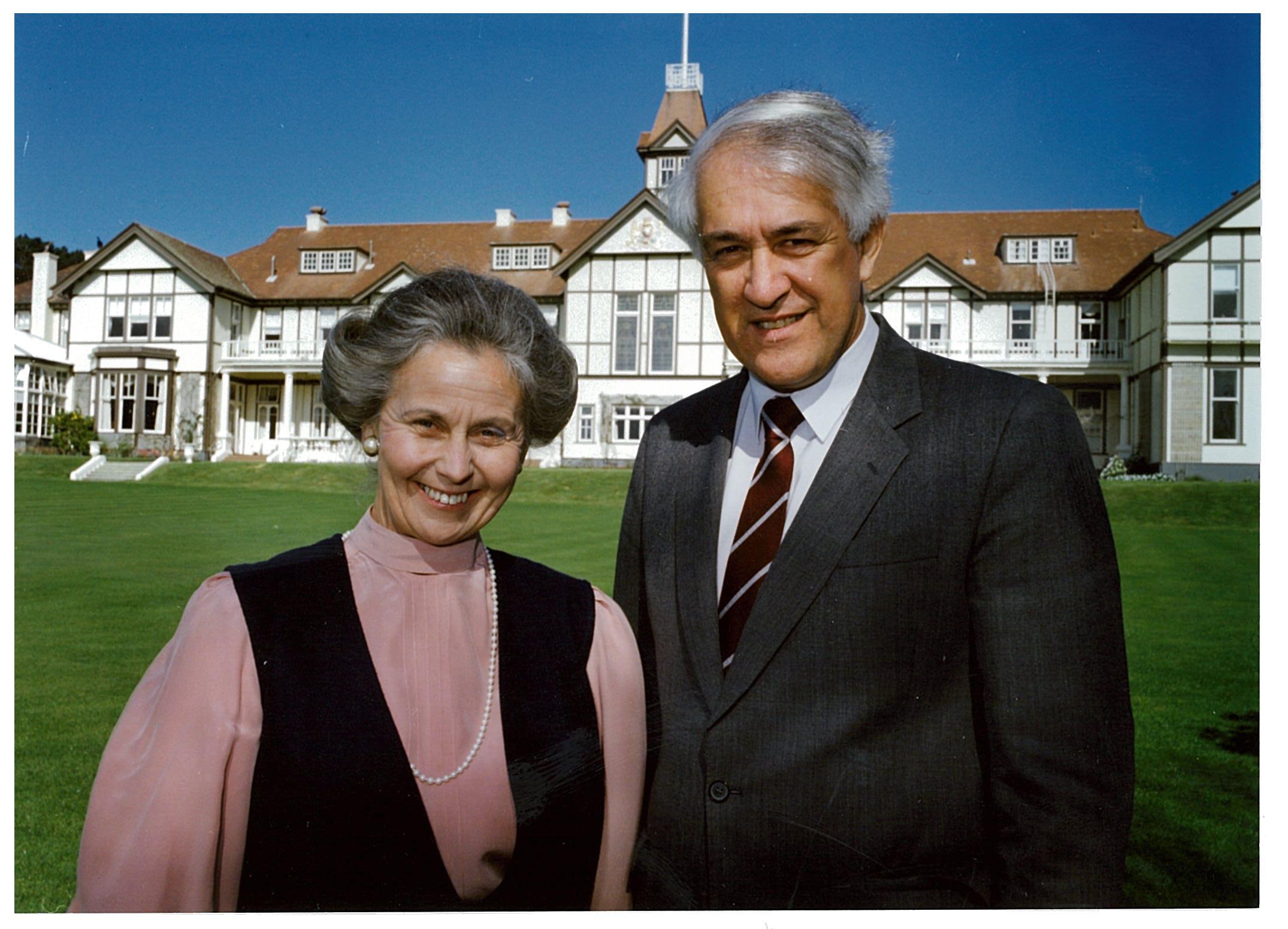

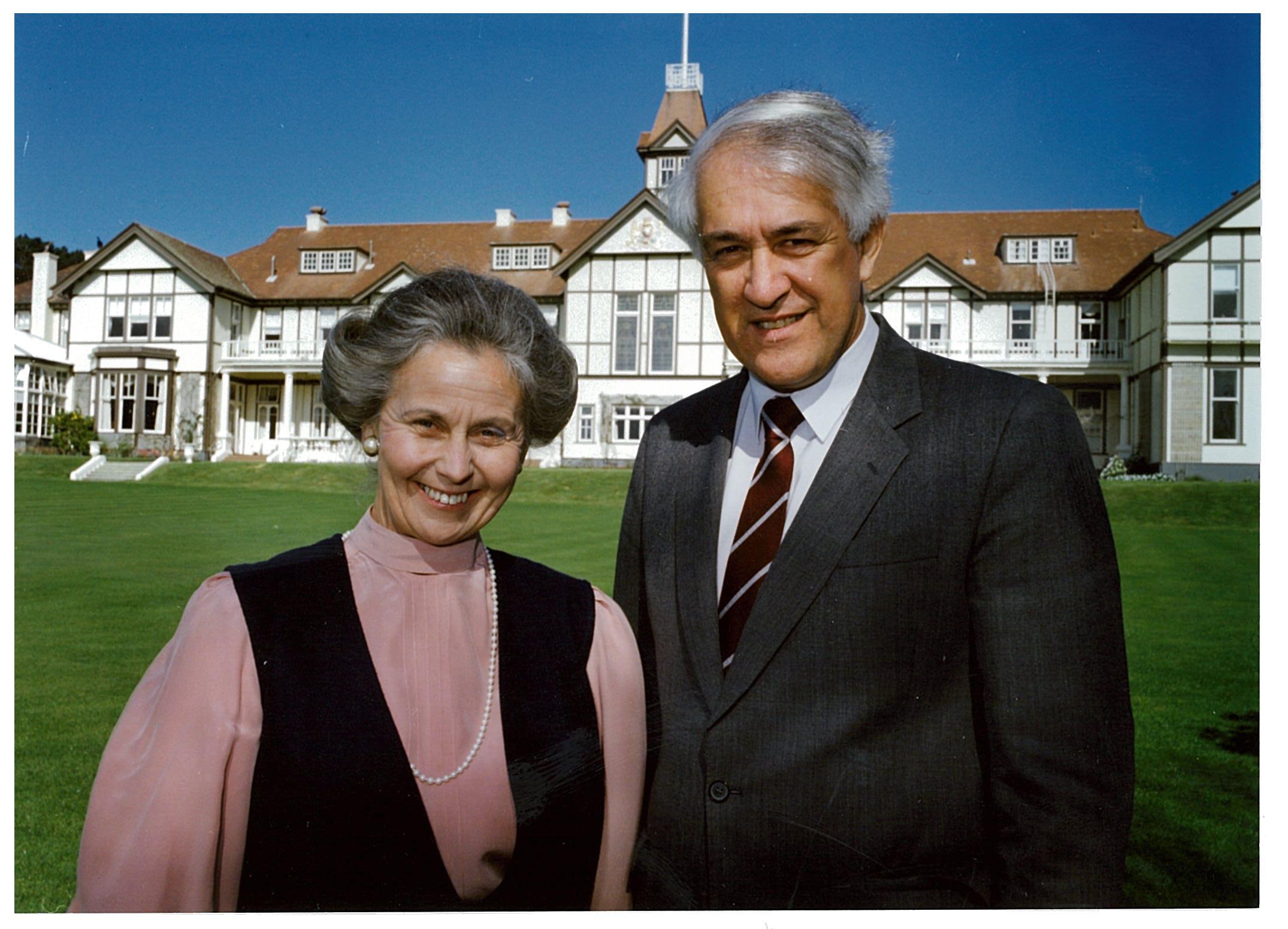

Governor-general

Appointment

On the advice of Prime MinisterDavid Lange

David Russell Lange ( ; 4 August 1942 – 13 August 2005) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 32nd prime minister of New Zealand from 1984 to 1989. A member of the New Zealand Labour Party, Lange was also the Minister of Education ...

, Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

appointed Reeves the 15th Governor-General of New Zealand

The governor-general of New Zealand () is the representative of the monarch of New Zealand, currently King Charles III. As the King is concurrently the monarch of 14 other Commonwealth realms and lives in the United Kingdom, he, on the Advice ...

effective from 20 November 1985. His appointment was met with some scepticism due to his previous political involvement in Citizens for Rowling, opposing the 1981 Springbok Tour, and the fact that he was an Anglican bishop. Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

Jim McLay

Sir James Kenneth McLay (born 21 February 1945) is a New Zealand diplomat and former politician. He served as the ninth deputy prime minister of New Zealand from 15 March to 26 July 1984. McLay was also Leader of the National Party and Leader ...

opposed the appointment on these grounds, asking "How can an ordained priest fulfil that onstitutionalrole?" Many Māori groups welcomed the appointment, with Sir James Henare arguing that "It must be a fruit of the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

to see a person from our people." He was the first (and up to the present the only) cleric

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

to hold the post. Moreover, as a member of the Puketapu ''hapū

In Māori language, Māori and New Zealand English, a ' ("subtribe", or "clan") functions as "the basic political unit within Māori society". A Māori person can belong to or have links to many hapū. Historically, each hapū had its own chief ...

'' of the Te Āti Awa

Te Āti Awa or Te Ātiawa is a Māori iwi with traditional bases in the Taranaki and Wellington regions of New Zealand. Approximately 17,000 people registered their affiliation to Te Āti Awa in 2001, with about 10,000 in Taranaki, 2,000 in We ...

of Taranaki

Taranaki is a regions of New Zealand, region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano Mount Taranaki, Taranaki Maunga, formerly known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the ...

, he was the first governor-general of Māori descent.

Tenure

As a clergyman, Reeves opted not to wear the military uniform of the governor-general. During his term, Reeves joined the Newtown Residents' Association, and invited members of that association to visitGovernment House, Wellington

Government House is the principal residence of the governor-general of New Zealand, the representative of the New Zealand head of state, King Charles III. Dame Cindy Kiro, who has been Governor-General since October 2021, currently resides ther ...

. He hosted the first open day at Government House on 7 October 1990, and employed the first public affairs officer, Cindy Beavis, to promote the governor-general's role.

Reeves remained in office until 20 November 1990. He was succeeded by Dame Catherine Tizard.

Controversies

During Reeves' tenure, the Fourth Labour Government made radical changes to the New Zealand economy, later known as Rogernomics. In November 1987 Reeves made comments critical of Rogernomics, stating that the reforms were creating "an increasingly stratified society". He was rebuked for these comments by Lange, but later stated in May 1988 "...the spirit of the market steals life from the vulnerable but the spirit of God gives life to all". Reeves later recalled that this marked a "parting of ways" with the government. Reeves also recalled "I had a little sense of being left alone and felt that I needed to be taken into the loop more, or be taken seriously." Reeves wrote to the Queen, but did not receive replies directly from the Queen. He said, "I used to write to the Queen and express my opinion about this and that going on it the country and I wouldn't get a direct reply from her but I would always get a lengthy reply from her private secretary, which I took was expressing her viewpoint." On a state visit toVanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (; ), is an island country in Melanesia located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of northern Australia, northeast of New Caledonia, east o ...

in 1988, Reeves was invited to kill a pig at a ceremony, creating controversy as he was patron of the Royal New Zealand Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. He later resigned as patron. This was followed by a similar incident when Reeves was a member of a party that shot an endangered bird during a trip to New Zealand's sub-Antarctic islands in December 1989. The bird was a light-mantled albatross and protected under the Wildlife Act 1953

Wildlife Act 1953 is an Act of Parliament in New Zealand. Under the act, the majority of native New Zealand vertebrate species are protected by law, and may not be hunted, killed, eaten or possessed. Violations may be punished with fines of up t ...

, however the Department of Conservation Southland operations manager Lou Sanson accepted that the shooting was accidental.

Retirement

After his retirement from the viceregal office, Reeves became theAnglican Consultative Council

The Anglican Consultative Council (ACC) is one of the four "Instruments of Communion" of the Anglican Communion. It was created by a resolution of the 1968 Lambeth Conference. The council, which includes Anglican bishops, other clergy, and lait ...

Observer at the United Nations in New York (1991–93) and Assistant Bishop of New York (1991–94). From 1994 until 1995 he served briefly as Dean of Te Whare Wānanga o Te Rau Kahikatea (the theological college of Te Pihopatanga o Aotearoa, and a constituent member of St John's College, Auckland). He was also Deputy Leader of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

Observer group to South Africa, Chair of the Nelson Mandela Foundation

The Nelson Mandela Foundation is a nonprofit organisation founded by Nelson Mandela in 1999 to promote Mandela's vision of freedom and equality for all. The chairman is Naledi Pandor. And the CEO is Dr. Mbongiseni Buthelezi.

Vision

The visi ...

, and Visiting Montague Burton Professor of International Relations at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

.

Reeves went on to chair the Fiji

Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islands—of which about ...

Constitution Review Commission from 1995 until 1997, culminating in Fiji's readmission to the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

, until its suspension in 2000. On 12 December 2007 it was reported that Reeves was involved with "secret talks" to resolve Fiji's year-long political crisis, following the 2006 Fijian coup d'état

The Fijian coup d'état of December 2006 was a coup d'état in Fiji carried out by Commodore (rank), Commodore Frank Bainimarama against Prime Minister of Fiji, Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase and President Josefa Iloilo. It was the culminatio ...

.

In 2004, Reeves made a statement in support of New Zealand republic, stating in an interview, "...if renouncing knighthoods was a prerequisite to being a citizen of a republic, I think it would be worth it."

Reeves served as the Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

of the Auckland University of Technology

Auckland University of Technology ( AUT; ) is a university in New Zealand, formed on 1 January 2000 when a former technical college (originally established in 1895) was granted university status. AUT is New Zealand's third largest university i ...

, from February 2005 until August 2011.

In July 2011, Reeves announced that he had been diagnosed with cancer, and therefore was retiring from all public responsibilities. He died from cancer on 14 August 2011, aged 78.

Honours and other awards

Reeves was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal (1977), he was appointed a Chaplain of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem in April 1982,Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised Order of chivalry, orders of chivalry; it is a part of the Orders, decorations, and medals ...

in the 1985 Queen's Birthday Honours, a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George on 6 November 1985, a Knight of Justice of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem in 1986, and a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order on 2 March 1986. In 1990 he became a Companion of the Queen's Service Order

The King's Service Order () established by royal warrant (document), royal warrant of Queen regnant, Queen Elizabeth II on 13 March 1975, is used to recognise "valuable voluntary service to the community or meritorious and faithful services to t ...

. Reeves was also made a Companion of the Order of Fiji.

There was some concern regarding Reeves' using the title ''Sir'', as members of the clergy in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

do not usually receive this title when knighted, and the same rule presumably applied to the Anglican Church in New Zealand. Moreover, clergy are traditionally not dubbed. To avoid placing the Queen in an awkward situation (governors-general would by tradition be knighted by her in person at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

), the prime minister of the time, David Lange

David Russell Lange ( ; 4 August 1942 – 13 August 2005) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 32nd prime minister of New Zealand from 1984 to 1989. A member of the New Zealand Labour Party, Lange was also the Minister of Education ...

, made Reeves a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised Order of chivalry, orders of chivalry; it is a part of the Orders, decorations, and medals ...

before meeting her. Consequently, when Reeves went to receive the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George from the Queen, he was already Sir Paul.

On Waitangi Day

Waitangi Day (, the national day of New Zealand, marks the anniversary of the initial signing—on 6 February 1840—of the Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty of Waitangi was an agreement towards British sovereignty by representatives of the The Cr ...

2007 Reeves was awarded New Zealand's highest honour, being admitted to the Order of New Zealand

The Order of New Zealand is the highest honour in the New Zealand royal honours system, created "to recognise outstanding service to the Crown and people of New Zealand in a civil or military capacity". It was instituted by royal warrant on 6 F ...

.

The University of Oxford conferred on him the degree of Doctor of Civil Law

Doctor of Civil Law (DCL; ) is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

At Oxford, the degree is a higher doctorate usually awarded on the basis of except ...

in 1985 and his college, St Peter's, appointed him an Honorary Fellow in 1981 and a Trustee in 1994. A Fellowship of St John's College, Auckland followed in 1989. He has received other honorary degrees, including an LLD of Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington (), also known by its shorter names "VUW" or "Vic", is a public university, public research university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of New Zealand Parliament, Parliament, and w ...

(1989), a DD of the General Theological Seminary, New York (1992), and the degree of ''Doctor Honoris Causa'' of the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

(1994).

Changes to the rules in 2006 allowed him to use the style ''The Honourable

''The Honourable'' (Commonwealth English) or ''The Honorable'' (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) (abbreviation: ''Hon.'', ''Hon'ble'', or variations) is an honorific Style ...

'' for life.

Arms

References

External links

Biography at Holy Trinity Cathedral website

* ttp://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/ideas/20110508 Radio NZ interview, 8 May 2011Sir Paul talks extensively about his life and work with interviewer Chris Laidlaw. (Listen directly or download options) {{DEFAULTSORT:Reeves, Paul Alfred 1932 births 2011 deaths Alumni of St Peter's College, Oxford Primates of New Zealand Anglican bishops of Auckland Anglican bishops of Waiapu Honorary Fellows of St Peter's College, Oxford People educated at Wellington College, Wellington Governors-general of New Zealand Knights of Justice of the Order of St John New Zealand republicans 20th-century Anglican archbishops in New Zealand Victoria University of Wellington alumni New Zealand Māori religious leaders Te Āti Awa people Members of the Order of New Zealand New Zealand Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George New Zealand Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Companions of the Queen's Service Order Companions of the Order of Fiji New Zealand Knights Bachelor Academics of the University of Edinburgh