Paul Foot (campaigner) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Paul Mackintosh Foot (8 November 1937 – 18 July 2004) was a British investigative journalist, political campaigner, author, and long-term member of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

''

''Journalism: Principles and Practice''

London: Sage, 2009, p. 103. He repeatedly returned to this case, to the occasional consternation of his editor but believed this practice would lead to new witnesses coming forward. Foot and his colleagues looked through many thousands of pages of evidence and statements. When his book ''Murder at the Farm: Who killed Carl Bridgewater?'' was published in 1986,

Archived

web.archive.com). Foot stayed at the ''Daily Mirror'' for 14 years, managing to survive at the paper during the years

''The Herald'' (Glasgow), 31 March 1993. He left the ''Mirror'' in 1993 when the paper refused to print articles critical of its new management and placed Foot on sick leave. "This is Stalinist psychiatry," he said at the time. "If you don't agree with us you must be mad." Banks also revealed Foot's salary as £55,000 at the time of the row over the unpublished column, although Foot himself said that it was actually a few thousand less. Foot rejoined ''Private Eye'', now with

"Fighting for legal aid is my family tradition"

''The Guardian'', 4 January 2014. and Tom Foot is a journalist. With Fermont, Foot had a daughter, Kate. Foot was a great admirer of West Indian cricket (he used to say that

Paul Foot died of a

Paul Foot died of a

''Unemployment – the Socialist Answer''

(1963), Glasgow: The Labour Worker. *''Immigration and Race in British Politics'' (1965), Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. *''The Politics of Harold Wilson'' (1968), Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. *''The Rise of Enoch Powell: An Examination of Enoch Powell’s Attitude to Immigration and Race'' (1969), London: Cornmarket Press, . *''Who Killed Hanratty?'' (1971), London: Cape, .

(1971), London: International Socialists.

(1973), England: International Socialists.

(1976), London: Rank and File Organising Committee.

(1977), London: Socialist Workers Party, . *''Red Shelley'' (1981), London: Sidgwick and Jackson, .

(1981), London: Socialists Unlimited, .

(1982), London: Socialist Workers Party, . *''The Helen Smith Story'' (1983), Glasgow: Fontana, (with Ron Smith).

(1986), London: Socialist Workers Party, . *''Murder at the Farm: Who Killed Carl Bridgewater?'' (1986), London: Sidgwick & Jackson, . *''Ireland: Why Britain Must Get Out'' (1989), London: Chatto & Windus, . *''Who Framed Colin Wallace?'' (1989), London: Macmillan, .

(1990), London: Bookmarks, . *''Words as Weapons: Selected Writing 1980–1990'' (1990), London: Verso, /0860915271. * * (Obituary of David Widgery.) *''Articles of Resistance'' (2000), London: Bookmarks, .

You Should Vote Socialist''

(2001), London: Bookmarks. . *''Lockerbie: The Flight from Justice'' (2001), London: Private Eye Special Issue. *''The Vote: How It Was Won and How It Was Undermined'' (2005), London: Viking, . *''Orwell & 1984: A Talk by Paul Foot'' (2021), London: Redwords, *''Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution: Two Talks by Paul Foot'' (2021), London: Redwords, .

Paul Foot Internet Archive

at Marxists.org

Foot's investigative reporting on the Lockerbie Bombing, published in Private Eye

Obituaries * Chris Harman

"Paul Foot 1937-2004"

''Socialist Worker'', Issue 1911, 24 July 2004. * Michael White and Sam Jon

"Paul Foot, radical columnist and campaigner, dies at 66"

''The Guardian'', 19 July 2004. * Tam Dalyell

(obituary), ''The Independent'', 20 July 2004. ** James Burleigh

(news article on his death), ''The Independent'', 19 July 2004.

"Veteran journalist Paul Foot dies"

BBC News, 19 July 2004.

''Socialist Review'' obituary

* Extracts from his final work ''The Vote''

"Last word on the revolution"

an

"Sisters at War"

in ''The Guardian'', 21 February 2005. Audio

MP3 Talks on Shelley and the Peasants Revolt by Foot

* Paul Foot on

Part 1Part 2Paul Foot Award

{{DEFAULTSORT:Foot, Paul 1937 births 2004 deaths 20th-century British journalists 21st-century British journalists Alumni of University College, Oxford British investigative journalists British Marxist journalists British socialists British Trotskyists Burials at Highgate Cemetery

Early life and education

Foot was born inHaifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

during the British mandate.

He was the son of Sir Hugh Foot (who was the last Governor of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and Jamaica and, as Lord Caradon, the Permanent Representative of the United Kingdom to the United Nations

Permanent may refer to:

Art and entertainment

* ''Permanent'' (film), a 2017 American film

* ''Permanent'' (Joy Division album)

* "Permanent" (song), by David Cook

*"Permanent", a song by Alex Lahey from ''The Answer Is Always Yes'', 2023

Other ...

from 1964 to 1970) and the grandson of Isaac Foot

Isaac Foot (23 February 1880 – 13 December 1960) was a British Liberal politician and solicitor.

Early life

Isaac Foot was born in Plymouth, the son of a carpenter and undertaker who was also named Isaac Foot, and educated at Plymouth Publ ...

, who had been a Liberal MP. He was a nephew of Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British politician who was Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposition from 1980 to 1983. Foot beg ...

, later leader

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

of the Labour Party,"Obituary: Paul Foot"''

The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'', 29 July 2004. to whom the younger Foot was close. He spent his youth at his uncle's house in Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

, in Italy with his grandmother and with his parents (who lived abroad) in Cyprus and Jamaica.

He was sent to what he described as "a ludicrously snobbish preparatory school ( Ludgrove) and an only slightly less absurd public school, Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

". Contemporaries at Shrewsbury included Richard Ingrams

Richard Reid Ingrams (born 19 August 1937) is an English journalist, a co-founder and second editor of the British satirical magazine ''Private Eye'', and founding editor of ''The Oldie'' magazine. He left the latter job at the end of May 2014.B ...

, Willie Rushton

William George Rushton (18 August 1937 – 11 December 1996) was an English cartoonist, comedian actor and satirist who co-founded the satirical magazine ''Private Eye''.

Early life

Rushton was born 18 August 1937 at 3 Wilbraham Place, Chelsea, ...

, Christopher Booker

Christopher John Penrice Booker (7 October 1937 – 3 July 2019) was an English journalist and author. He was a founder and first editor of the satirical magazine '' Private Eye'' in 1961. From 1990 onward he was a columnist for ''The Sunday Te ...

, and several other friends with whom he later become involved in ''Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely recognised ...

''.

Anthony Chenevix-Trench

Anthony Chenevix-Trench (10 May 1919 – 21 June 1979) was a British schoolteacher, classics scholar and alleged child sexual abuser. He was born in British India, educated at Shrewsbury School and Christ Church, Oxford, and served in the Second ...

, later the Headmaster of Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, was Foot's Housemaster at Shrewsbury School between 1952 and 1955, a time when corporal punishment in all schools was commonplace. In adult life, Foot exposed the ritual beatings that Chenevix-Trench had given. Nick Cohen

Nicholas Cohen (born 1961) is a British journalist, author, and political commentator. He was previously a columnist for '' The Observer'' and is currently one for ''The Spectator''. Following accusations of sexual harassment, he left ''The O ...

wrote in Foot's obituary in ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

'':"Even by the standards of England's public schools, Anthony Chenevix-Trench, his housemaster at Shrewsbury, was a flagellomaniac. Foot recalled, 'He would offer his culprit an alternative: four strokes with the cane, which hurt; or six with the strap, with trousers down, which didn't. Sensible boys always chose the strap, despite the humiliation, and Trench, quite unable to control his glee, led the way to an upstairs room, which he locked, before hauling down the miscreant's trousers, lying him face down on a couch and lashing out with a belt." Nick Cohen quotes from Foot's 1996 ''London Review of Books'' article.Foot first detailed Chenevix-Trench's behaviour for ''Private Eye'' in 1969, an experience described by Cohen as one of Foot's happiest days in journalism. After his

national service

National service is a system of compulsory or voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act ...

in Jamaica, Foot was reunited with Ingrams at University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies f ...

at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, where he read jurisprudence, and wrote for ''Isis

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

'', one of the student publications at the university. He briefly edited ''Isis'', resulting in the publication being temporarily banned by the university authorities after Foot began to publish articles that found fault with university lectures.

Years in Glasgow

Via hisuncle

An uncle is usually defined as a male relative who is a sibling of a parent or married to a sibling of a parent, as well as the parent of the cousins. Uncles who are related by birth are second-degree relatives. The female counterpart of an un ...

, Paul Foot made the acquaintance of Hugh Cudlipp

Hubert Kinsman Cudlipp, Baron Cudlipp, OBE (28 August 1913 – 17 May 1998), was a Welsh journalist and newspaper editor noted for his work on the ''Daily Mirror'' in the 1950s and 1960s. He served as chairman of the Mirror Group group of ...

, the editorial director of Mirror Group Newspapers, who offered him a job with the company and Foot joined the '' Daily Record'' in Glasgow. He was expected "to sort out the Trots" in his journalism, but instead the experience of living in the Scottish city changed his whole outlook.

Foot met workers from shipyards and engineering firms who had joined the Young Socialists. He read, for the first time, Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg ( ; ; ; born Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary and Marxist theorist. She was a key figure of the socialist movements in Poland and Germany in the early 20t ...

, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, and the multi-volume biography of Trotsky by Isaac Deutscher

Isaac Deutscher (; 3 April 1907 – 19 August 1967) was a Polish Marxist writer, journalist and political activist who moved to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of World War II. He is best known as a biographer of Leon Trotsky and Joseph S ...

.

While living in Glasgow he met Tony Cliff

Tony Cliff (born Yigael Glückstein, ; 20 May 1917 – 9 April 2000) was a Trotskyist activist. Born to a Jewish family in Ottoman Palestine, he moved to Britain in 1947 and by the end of the 1950s had assumed the pen name of Tony Cliff. A fo ...

, "an ebullient Palestinian Jew". Cliff argued that Russia was state capitalist

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capital accumulation, ce ...

and that Russian workers were cut off from economic and political power as much as, if not more than, those in the West. Persuaded by what he heard and saw, in 1963 Foot joined the International Socialists, the group in which Cliff had a leading role, and the organisational forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

"Of all the many lessons I learnt in those three years in Glasgow," he wrote later, "the one which most affected my life was a passing remark by Rosa Luxemburg. She predicted that, however strong people's socialist commitment, as soon as they are involved even to the slightest degree in managing the system on behalf of capitalists, they will be lost to the socialist cause."

Foot covered the 1962 West Lothian by-election as a political reporter for the ''Daily Record''. He asked of the Labour candidate, Tam Dalyell

Sir Thomas Dalyell, 11th Baronet ( ; 9 August 1932 – 26 January 2017), known as Tam Dalyell, was a Scottish politician who served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Linlithgow (formerly West Lothian) from 1962 to 2005. A member of the Labour ...

: "How on earth is it that the West Lothian Constituency Labour Party with six coal-mines in the constituency can choose somebody from Eton and King's College, Cambridge, as their candidate?" H. B. Boyne, a political correspondent for the ''Daily Telegraph'', reminded Foot of his own background. The incident did not stop the two men becoming friends.

Journalism and public career (1964–1978)

In 1964, he returned to London and began to work for ''The Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot Plasma (physics), plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as ...

'', as the trade union newspaper, the '' Daily Herald'', had become, in a department called Probe. The intention was to investigate and publish stories behind the news but the Probe team resigned after six months. "The man in charge turned out to be a former ''Daily Express'' City editor."

Foot left to work, part-time, on the Mandrake column on ''The Sunday Telegraph

''The Sunday Telegraph'' is a British broadsheet newspaper, first published on 5 February 1961 and published by the Telegraph Media Group, a division of Press Holdings. It is the sister paper of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Tele ...

''. He had contributed articles to ''Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely recognised ...

'' since 1964 but decided, in February 1967, to take a cut in salary and join the staff of the magazine on a full-time basis, working with its editor, Richard Ingrams

Richard Reid Ingrams (born 19 August 1937) is an English journalist, a co-founder and second editor of the British satirical magazine ''Private Eye'', and founding editor of ''The Oldie'' magazine. He left the latter job at the end of May 2014.B ...

and Peter Cook

Peter Edward Cook (17 November 1937 – 9 January 1995) was an English comedian, actor, satirist, playwright and screenwriter. He was the leading figure of the British satire boom of the 1960s, and he was associated with the anti-establishmen ...

, by now in possession of a controlling interest in the magazine. When asked about the decision later, Foot would say he could not resist the prospect of two whole pages with complete freedom to write whatever he liked. "Writing for ''Private Eye'' is the only journalism I have ever been engaged in which is pure enjoyment. It is free publishing of the most exhilarating kind."

Foot got on very well with Cook, only realising after the latter's death in 1995 how much they had in common, "We both were born in the same week, into the same sort of family. His father, like mine, was a colonial servant rushing round the world hauling down the imperial flag. Both fathers shipped their eldest sons back to public school education in England. We both spent our school holidays with popular aunts and uncles in the West Country."

Foot's first stint at ''Private Eye'' lasted until 1972 when, according to Patrick Marnham, Foot was sacked by Ingrams, who had come to the conclusion that Foot's copy was being unduly influenced by his contacts in the International Socialists. Ingrams has denied this, writing, "It was said at the time that he and I had fallen out over political issues. In fact, we very seldom disagreed about such things, the only tension arising from Paul's belief that whenever there was a strike he had to support the union regardless of any rights or wrongs." In October 1972, he left to join the ''Socialist Worker

''Socialist Worker'' is the name of several newspapers currently or formerly associated with the International Socialist Tendency (IST). It is a weekly newspaper published by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the United Kingdom since 1968, a ...

'', the weekly newspaper of the International Socialists, "confident that a revolution was coming", as he explained decades later. He became editor in 1974. He unsuccessfully fought the Birmingham Stechford by-election in 1977 for the SWP, winning 1 per cent of the vote.

Career (1978–2004)

Six years later he returned to ''Private Eye'' but was poached in 1979 by the editor of the ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily Tabloid journalism, tabloid newspaper. Founded in 1903, it is part of Mirror Group Newspapers (MGN), which is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the tit ...

'', Mike Molloy

Michael Molloy (born 22 December 1940) is a British author and former newspaper editor and cartoonist.

Biography

Born in Perivale, Molloy studied at Ealing Junior School and the Ealing School of Art before working at the '' Sunday Pictorial' ...

, who offered him a weekly investigative page of his own with one condition, that he was not to make propaganda for the SWP. In 1980, Foot began to look into the case of the " Bridgewater Four", who had been convicted the previous year of killing Stourbridge

Stourbridge () is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. Situated on the River Stour, Worcestershire, River Stour, the town lies around west of Birmingham,

at the southwester ...

newspaper boy Carl Bridgewater.Tony Harcup''Journalism: Principles and Practice''

London: Sage, 2009, p. 103. He repeatedly returned to this case, to the occasional consternation of his editor but believed this practice would lead to new witnesses coming forward. Foot and his colleagues looked through many thousands of pages of evidence and statements. When his book ''Murder at the Farm: Who killed Carl Bridgewater?'' was published in 1986,

Stephen Sedley

Sir Stephen John Sedley (born 9 October 1939) is a British lawyer. He worked as a judge of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales from 1999 to 2011 and was a visiting professor at the University of Oxford from 2011 to 2015.

Early life and ed ...

wrote in the ''London Review of Books

The ''London Review of Books'' (''LRB'') is a British literary magazine published bimonthly that features articles and essays on fiction and non-fiction subjects, which are usually structured as book reviews.

History

The ''London Review of Book ...

'' that Foot had not managed to "answer his own question" but did succeed in demonstrating "that if a jury had known what is now known about the case, it would not have inculpated" the defendants. After nearly 20 years in prison, their convictions were overturned at the Court of Appeal

An appellate court, commonly called a court of appeal(s), appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to Hearing (law), hear a Legal case, case upon appeal from a trial court or other ...

in February 1997 and the three surviving men (one had died in prison) were released.David Graves, "Bridgewater Four convictions quashed", ''Daily Telegraph'' 31 July 1997.Archived

web.archive.com). Foot stayed at the ''Daily Mirror'' for 14 years, managing to survive at the paper during the years

Robert Maxwell

Ian Robert Maxwell (born Ján Ludvík Hyman Binyamin Hoch; 10 June 1923 – 5 November 1991) was a Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovak-born British media proprietor, politician and fraudster.

After escaping the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, ...

was in control from 1984. Foot wrote in 2000: "Maxwell demeaned everyone who worked for him, myself included, but I was able by sheltering behind the editor to protect myself from his more monstrous excesses." He finally fell out with the new ''Mirror'' editor, David Banks, in March 1993, nearly 17 months after Maxwell's death. Banks, he claimed, had accused him of being "mad" and a contemporaneous boardroom coup had introduced, according to Foot, a "systematic campaign of union-busting" at the company."Paul Foot resigns from Mirror"''The Herald'' (Glasgow), 31 March 1993. He left the ''Mirror'' in 1993 when the paper refused to print articles critical of its new management and placed Foot on sick leave. "This is Stalinist psychiatry," he said at the time. "If you don't agree with us you must be mad." Banks also revealed Foot's salary as £55,000 at the time of the row over the unpublished column, although Foot himself said that it was actually a few thousand less. Foot rejoined ''Private Eye'', now with

Ian Hislop

Ian David Hislop (born 13 July 1960) is a British journalist, satirist, and television personality. He is the editor of the satirical magazine '' Private Eye'', a position he has held since 1986. He has appeared on many radio and television pr ...

as the magazine's editor, and began his regular column for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

''. From 2001, he was a Socialist Alliance candidate for several offices. In the Hackney mayoral election in 2002 he came third, beating the Liberal Democrat

Several political parties from around the world have been called the Liberal Democratic Party, Democratic Liberal Party or Liberal Democrats. These parties have usually followed liberalism as ideology, although they can vary widely from very progr ...

candidate. Foot also stood in the London region for the Respect

Respect, also called esteem, is a positive feeling or deferential action shown towards someone or something considered important or held in high esteem or regard. It conveys a sense of admiration for good or valuable qualities. It is also th ...

coalition in the 2004 European elections.

Foot's last book, ''The Vote: How It Was Won and How It Was Undermined'', was published posthumously in 2005. His friend and ''Private Eye'' colleague Francis Wheen, in his ''Guardian'' review, concluded: "Passionate, energetic and invincibly cheerful: the qualities of his final book are also a monument to the man himself."

Writing

Foot wrote '' Red Shelley'' (1981), a book that exalted the radical politics ofPercy Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 1792 – 8 July 1822) was an English writer who is considered one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame durin ...

's poetry. Foot was a bibliophile, following in the steps of his grandfather Isaac and uncle Michael, and was also the author of a publication about the radical union leader A. J. Cook.

Awards and campaign journalism

Paul Foot was named journalist of the year in the '' What The Papers Say'' Awards in 1972 and 1989 and campaigning journalist of the year in the 1980British Press Awards

The Press Awards, formerly the British Press Awards, is an annual ceremony that celebrates the best of British journalism.

History

Established in 1962 by ''The People'' and '' World's Press News'', the first award ceremony for the then-named Ha ...

; he won the '' George Orwell Prize for Journalism'' in 1995 with Tim Laxton, won the journalist of the decade prize in the ''What The Papers Say'' Awards in 2000, and the James Cameron

James Francis Cameron (born August 16, 1954) is a Canadian filmmaker, who resides in New Zealand. He is a major figure in the post-New Hollywood era and often uses novel technologies with a Classical Hollywood cinema, classical filmmaking styl ...

special posthumous Award in 2004.

His best known work was in the form of campaign journalism, including his exposure of corrupt architect John Poulson

John Garlick Llewellyn Poulson (14 April 1910 – 31 January 1993) was a British architectural designer and businessman who caused a major political scandal when his use of bribery was disclosed in 1972. The highest-ranking figure to be forced ...

and, most notably, his prominent role in the campaigns to overturn the convictions of the Birmingham Six

The Birmingham Six were six men from Northern Ireland who were each sentenced to life imprisonment in 1975 following their false convictions for the 1974 Birmingham pub bombings. Their convictions were declared unsafe and unsatisfactory and q ...

, which eventually succeeded in 1991. Foot also said that a former British intelligence officer, Colin Wallace

John Colin Wallace (born June 1943) is a British former member of Army Intelligence in Northern Ireland and a psychological warfare specialist. He refused to become involved in the Intelligence-led 'Clockwork Orange' project, which was an at ...

, had been framed for manslaughter with a view to suppressing Wallace's allegations of collusion between British forces and Loyalist paramilitaries in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

during the 1970s.

Foot took a particular interest in the conviction of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi

Abdelbaset Ali Mohamed al-Megrahi ( , ; 1 April 1952 – 20 May 2012) was a Libyan convicted of the Lockerbie bombing of Pan Am flight 103. He was head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines, director of the Centre for Strategic Studies in Trip ...

for the Lockerbie bombing

Pan Am Flight 103 (PA103/PAA103) was a regularly scheduled Pan Am transatlantic flight from Frankfurt to Detroit via a stopover in London and another in New York City. Shortly after 19:00 on 21 December 1988, the Boeing 747 "Clipper Maid of th ...

, firmly believing Megrahi to have been a victim of a miscarriage of justice

A miscarriage of justice occurs when an unfair outcome occurs in a criminal or civil proceeding, such as the conviction and punishment of a person for a crime they did not commit. Miscarriages are also known as wrongful convictions. Innocent ...

at the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial

The Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial began on 3 May 2000, more than 11 years after the destruction of Pan Am Flight 103 on 21 December 1988. The 36-week bench trial took place at a specially convened Scottish Court in the Netherlands set up under ...

.

He also worked, though without success, to gain a posthumous pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

for James Hanratty

James Hanratty (4 October 1936 – 4 April 1962), also known as the A6 Murderer, was a British criminal who was one of the final eight people in the UK to be executed before capital punishment was abolished. He was hanged at HM Prison Bedford ...

, who was hanged

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

in 1962 for the A6 murder. It was a position he maintained even after DNA evidence

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

in 1999 confirmed Hanratty's guilt.

Personal life

Paul Foot was married twice, to Monica (née Beckinsale, 1962–70) and Rose (Roseanne, née Harvey, 1971–93) and had a long-term relationship with Clare Fermont. He had two sons by his first wife, one son by his second, and a daughter by his relationship with Fermont: John Foot is an academic and writer specialising in Italy, Matt Foot is a solicitor,Simon Hattenstone"Fighting for legal aid is my family tradition"

''The Guardian'', 4 January 2014. and Tom Foot is a journalist. With Fermont, Foot had a daughter, Kate. Foot was a great admirer of West Indian cricket (he used to say that

George Headley

George Alphonso Headley Order of Distinction, OD, Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, MBE (30 May 1909 – 30 November 1983) was a Jamaican cricketer who played 22 Test cricket, Test matches, mostly before World War II. Co ...

had taught him to bat) and a faithful follower of Plymouth Argyle Football Club. He was also a batsman and golfer.

Death and memorials

Paul Foot died of a

Paul Foot died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

at the age of 66. A tribute issue of the '' Socialist Review'', on whose editorial board Foot sat for 19 years, collected together many of his articles, while issue 1116 of ''Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely recognised ...

'' included a tribute to Foot from the many people with whom he had worked. Three months after his death, on 10 October 2004, there was a full house at the Hackney Empire

Hackney Empire is a theatre on Mare Street, in Hackney in the London Borough of Hackney. Originally designed by Frank Matcham it was built in 1901 as a music hall, and expanded in 2001. Described by ''The Guardian'' as "the most beautiful theat ...

in London for an evening's celebration of his life. The following year, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' and ''Private Eye'' jointly set up the Paul Foot Award

The Paul Foot Award is an annual award run by ''Private Eye'', for investigative or campaigning journalism, in memory of journalist Paul Foot, who died in 2004.

The award was originally set up in 2005 by ''The Guardian'' and ''Private Eye'', fo ...

for investigative or campaigning journalism, with an annual £10,000 prize fund.

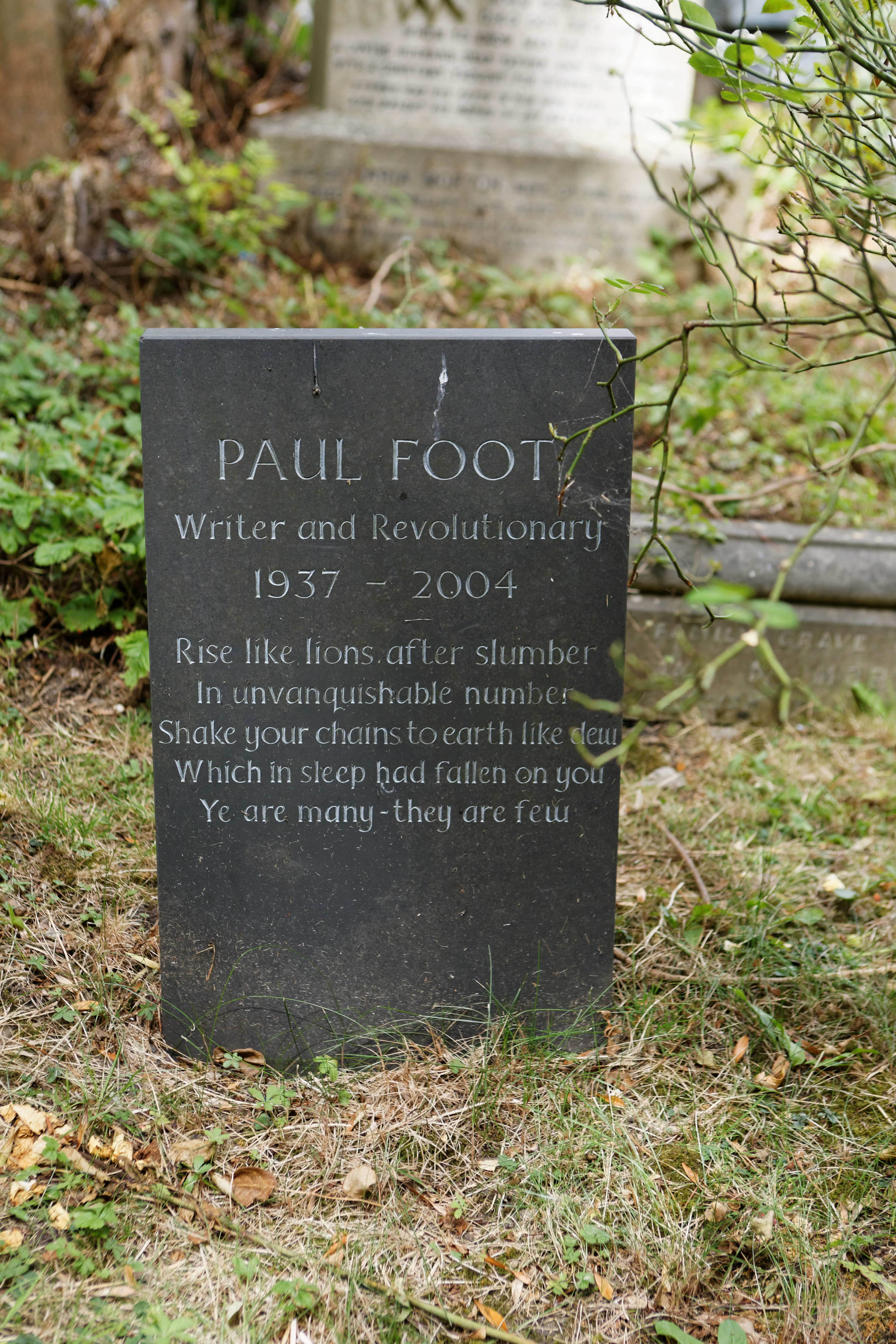

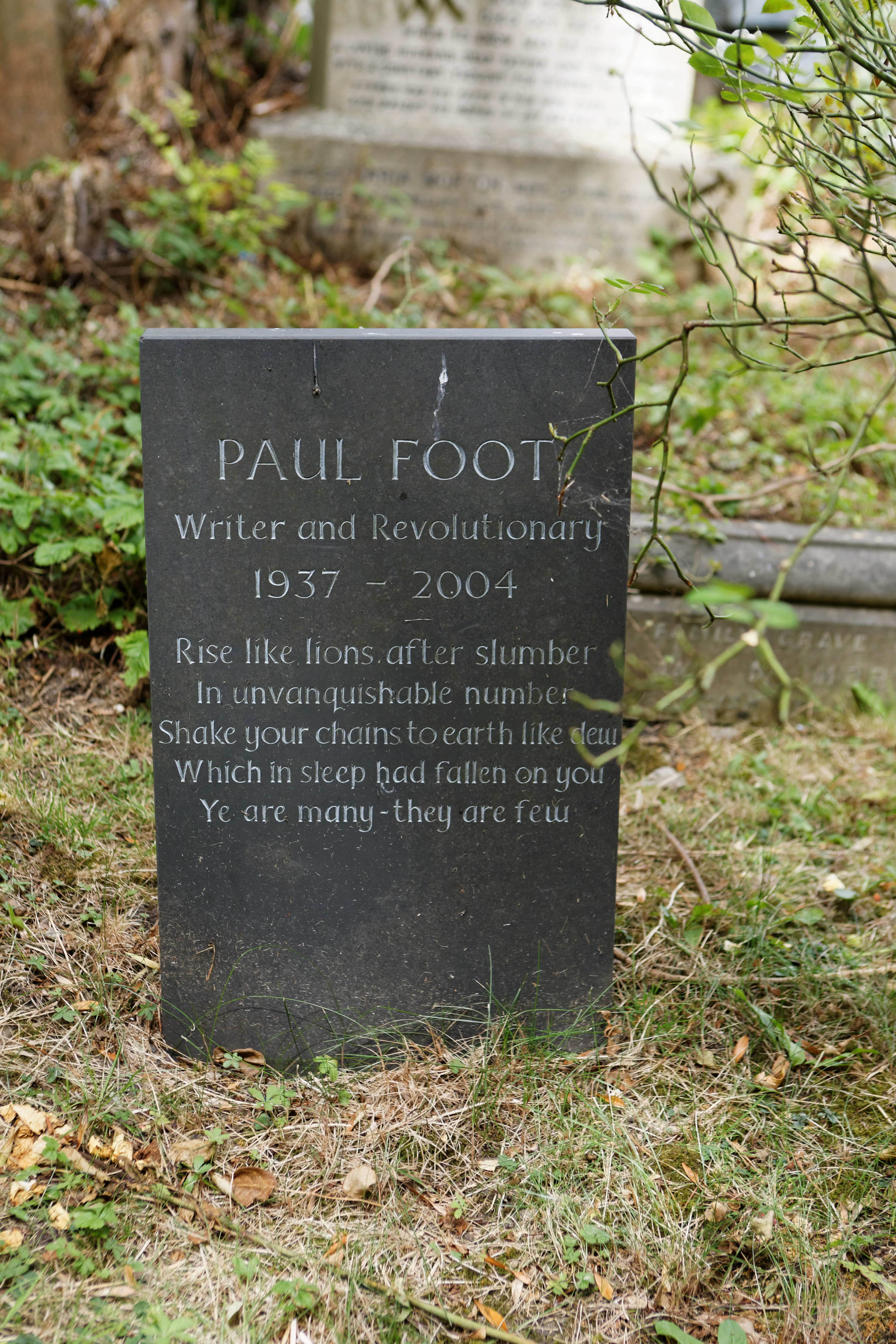

Foot is buried in Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in North London, England, designed by architect Stephen Geary. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East sides. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for so ...

, London, near Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

's tomb, with the grave of Chris Harman

Christopher John Harman (8 November 1942 – 7 November 2009) was a British journalist and political activist, and a member of the Central Committee of the Socialist Workers Party. He was an editor of '' International Socialism'' and '' S ...

, another long-time SWP member, adjacent to Foot's.

Publications

''Unemployment – the Socialist Answer''

(1963), Glasgow: The Labour Worker. *''Immigration and Race in British Politics'' (1965), Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. *''The Politics of Harold Wilson'' (1968), Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. *''The Rise of Enoch Powell: An Examination of Enoch Powell’s Attitude to Immigration and Race'' (1969), London: Cornmarket Press, . *''Who Killed Hanratty?'' (1971), London: Cape, .

(1971), London: International Socialists.

(1973), England: International Socialists.

(1976), London: Rank and File Organising Committee.

(1977), London: Socialist Workers Party, . *''Red Shelley'' (1981), London: Sidgwick and Jackson, .

(1981), London: Socialists Unlimited, .

(1982), London: Socialist Workers Party, . *''The Helen Smith Story'' (1983), Glasgow: Fontana, (with Ron Smith).

(1986), London: Socialist Workers Party, . *''Murder at the Farm: Who Killed Carl Bridgewater?'' (1986), London: Sidgwick & Jackson, . *''Ireland: Why Britain Must Get Out'' (1989), London: Chatto & Windus, . *''Who Framed Colin Wallace?'' (1989), London: Macmillan, .

(1990), London: Bookmarks, . *''Words as Weapons: Selected Writing 1980–1990'' (1990), London: Verso, /0860915271. * * (Obituary of David Widgery.) *''Articles of Resistance'' (2000), London: Bookmarks, .

You Should Vote Socialist''

(2001), London: Bookmarks. . *''Lockerbie: The Flight from Justice'' (2001), London: Private Eye Special Issue. *''The Vote: How It Was Won and How It Was Undermined'' (2005), London: Viking, . *''Orwell & 1984: A Talk by Paul Foot'' (2021), London: Redwords, *''Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution: Two Talks by Paul Foot'' (2021), London: Redwords, .

See also

* Alternative theories of the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103References

Further reading

* *External links

Paul Foot Internet Archive

at Marxists.org

Foot's investigative reporting on the Lockerbie Bombing, published in Private Eye

Obituaries * Chris Harman

"Paul Foot 1937-2004"

''Socialist Worker'', Issue 1911, 24 July 2004. * Michael White and Sam Jon

"Paul Foot, radical columnist and campaigner, dies at 66"

''The Guardian'', 19 July 2004. * Tam Dalyell

(obituary), ''The Independent'', 20 July 2004. ** James Burleigh

(news article on his death), ''The Independent'', 19 July 2004.

"Veteran journalist Paul Foot dies"

BBC News, 19 July 2004.

''Socialist Review'' obituary

* Extracts from his final work ''The Vote''

"Last word on the revolution"

an

"Sisters at War"

in ''The Guardian'', 21 February 2005. Audio

MP3 Talks on Shelley and the Peasants Revolt by Foot

* Paul Foot on

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

Part 1

{{DEFAULTSORT:Foot, Paul 1937 births 2004 deaths 20th-century British journalists 21st-century British journalists Alumni of University College, Oxford British investigative journalists British Marxist journalists British socialists British Trotskyists Burials at Highgate Cemetery

Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

People educated at Ludgrove School

People educated at Shrewsbury School

Presidents of the Oxford Union

Private Eye contributors

Respect Party parliamentary candidates

Socialist Workers Party (UK) members

Sons of life peers

The Guardian journalists