Partition Of Babylon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

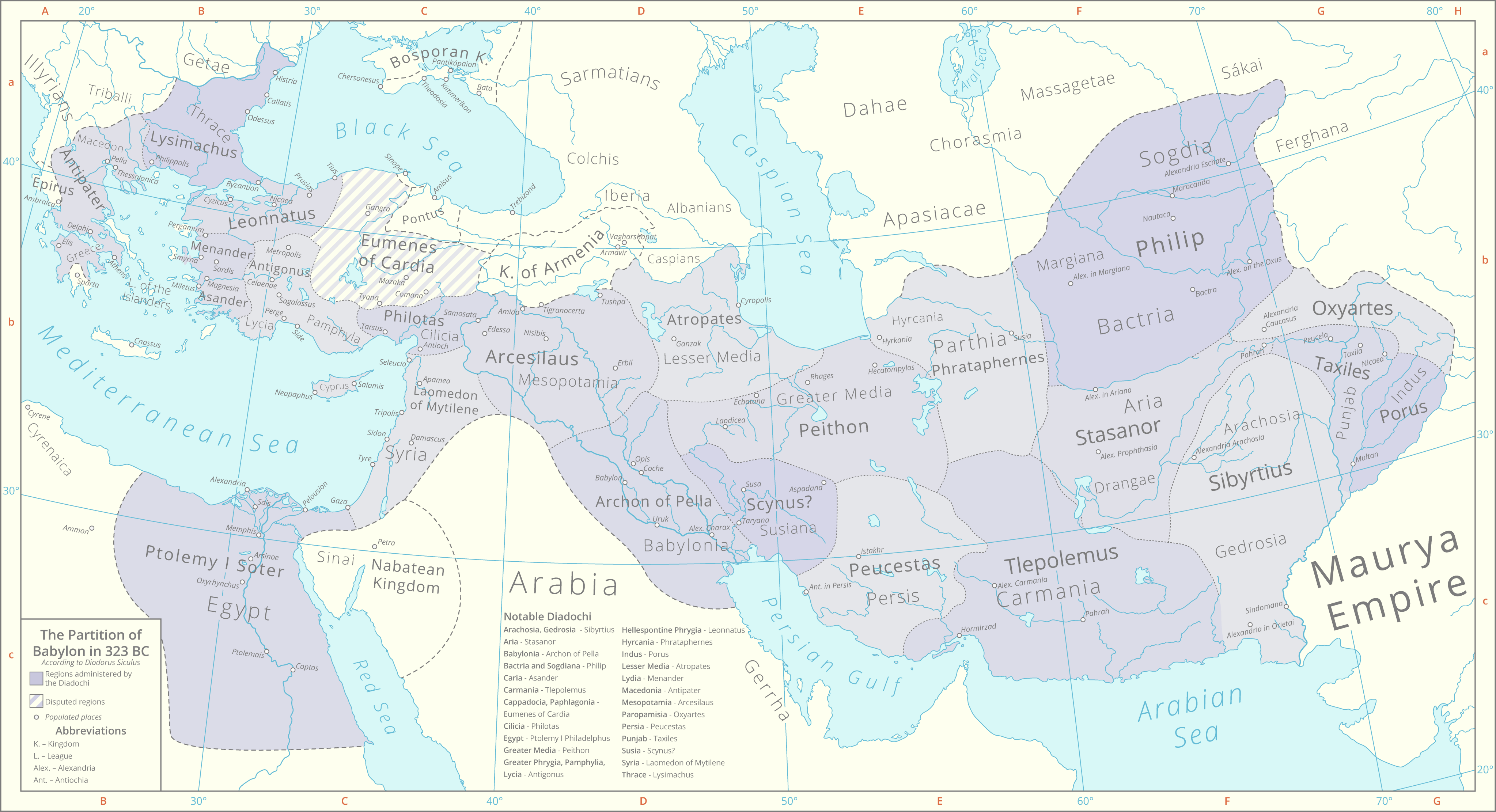

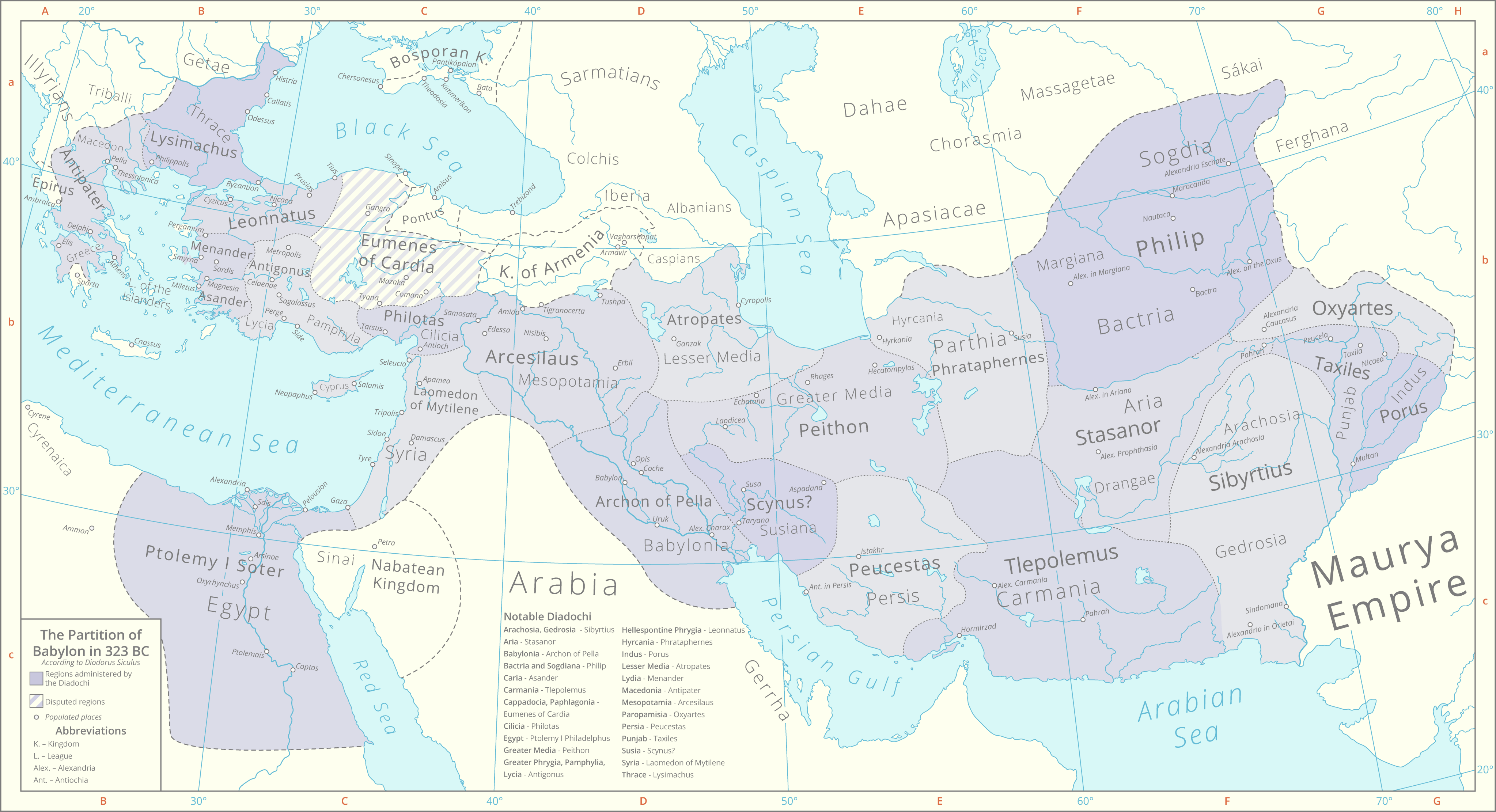

The Partition of Babylon was the first of the conferences and ensuing agreements that divided the territories of

The Partition of Babylon was the first of the conferences and ensuing agreements that divided the territories of

Territorial boundaries were to remain in question for the rest of the century, until 300 BC. The two main sources on the "Partition of Babylon" use equivocal language concerning it. According to

Territorial boundaries were to remain in question for the rest of the century, until 300 BC. The two main sources on the "Partition of Babylon" use equivocal language concerning it. According to

XVIII, 3

/ref> The Byzantine bishop Photius (c. 820–893) produced an

Continuation (codex 92)

/ref> The second is Dexippus's ''History'' of events after Alexander (codex 82),Dexippus

History (codex 82)

/ref> which itself seems to be based on Arrian's account; compare Arrian:

IV, 23

and therefore his retention of these satrapies corresponds with Arrian's statement that: "At the same time several provinces remained under their native rulers, according to the arrangement made by Alexander, and were not affected by the distribution." ;Lesser

VII, 4

;Greater

The Partition of Babylon was the first of the conferences and ensuing agreements that divided the territories of

The Partition of Babylon was the first of the conferences and ensuing agreements that divided the territories of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. It was held at Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

in June 323 BC.

Alexander’s death at the age of 32 had left an empire that stretched from Greece all the way to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. The issue of succession resulted from the claims of the various supporters of Philip Arrhidaeus (Alexander’s half-brother), and the as-of-then unborn child of Alexander and Roxana, among others.

The settlement saw Arrhidaeus and Alexander’s child designated as joint kings with Perdiccas serving as regent. The territories of the empire became satrapies divided between the senior officers of the Macedonian army and some local governors and rulers. The partition was solidified at the further agreements at Triparadisus and Persepolis

Persepolis (; ; ) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by the southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian cultural heritage sites and ...

over the following years and began the series of conflicts that comprise the Wars of the Diadochi

The Wars of the Diadochi (, Romanization of Greek, romanized: ', ''War of the Crown Princes'') or Wars of Alexander's Successors were a series of conflicts fought between the generals of Alexander the Great, known as the Diadochi, over who would ...

. The term "Partition of Babylon" is a modern designation.

Definition of partition

Territorial boundaries were to remain in question for the rest of the century, until 300 BC. The two main sources on the "Partition of Babylon" use equivocal language concerning it. According to

Territorial boundaries were to remain in question for the rest of the century, until 300 BC. The two main sources on the "Partition of Babylon" use equivocal language concerning it. According to Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

, a coalition of factions in the army "established" (''kathestesan'') that Arridaeus, son of Philip, should be king, and his name changed to Philip. Perdiccas, "to whom the dying king had given his finger-ring", was to be "caretaker" (''epimeletes''). The most worthy of the companions were to "succeed" (''paralabein'') to the satrapies, and obey the king and Perdiccas. Alexander and Philip before him had not merely been kings, they were "leaders" (''hegemones'') in the League of Corinth

The League of Corinth, also referred to as the Hellenic League (, ''koinòn tõn Hellḗnōn''; or simply , ''the Héllēnes''), was a federation of Greek states created by Philip IIDiodorus Siculus, Book 16, 89. «διόπερ ἐν Κορί� ...

. Perdiccas was not merely to be the king's manager, he was to succeed to the Hegemony, which apparently the king did not. "Holding a council" (''sunedreusas'') as Hegemon, he assigned the various satrapies.

A catalogue of assignments follows. To this point it appears to be a list of successions, or promotions. Then Diodorus says: "the satrapies were partitioned (''emeristhesan'') in this way." The word is based on "part" (''meros''). It is not the Companions who are being promoted to Satraps, but the satrapies that are being divided and distributed to the Companions, which is a different concept. Satraps who own their satrapies do not need a king. Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus (; ) was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alex ...

, who wrote more extensively about the transition, says much the same thing. Holding a "council of the chief men" (''consilium principum virorum''); that is, the ''sunedrion'', Perdiccas divides the ''imperium'', or "Empire", between the top rank (''summa'') held by the king and the satrapes. He clarifies, "the empire having been divided into parts" (''divisis imperii partibus''), or partitioned between individuals who could defend or choose to expand them. He points out that those who a little before had been ''ministri'' under the king now fought to expand their own "kingdoms" (''regna'') under the mask of fighting for the empire.

Johann Gustav Droysen, innovator of the historical concepts of a Hellenistic Period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

divided it into a Diadochi

The Diadochi were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period from the Mediterran ...

Period and an Epigoni Period, and adopted Curtius' view of the result of the ''sunedrion'' at Babylon as a partition. He refers to the "First Partition of the Satrapies" (''Erste Verteilung der Satrapien''). Droysen's view is that Perdiccas distributed the satrapies with a view toward removing his opponents from among the Companions at the scene; thus the changes were never legitimate promotions of Diadochi

The Diadochi were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period from the Mediterran ...

, persons who expected advancement within the Empire. George Grote, the Parliamentarian-turned-historian within the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, did not share this skeptical view, at least of the assignments at Babylon. He says: "All the above-named officers were considered as local lieutenants, administering portions of an empire one and indivisible, under Arridaeus. ... No one at this moment talked of dividing the empire." Droysen's view prevailed. Contemporaneously with the two, another parliamentarian and historian, Edward Bunbury, was using the concepts of Droysen, not Grote, in the standard reference works being chaired by William Smith.

The differences in point of view derive from the ancient historians themselves. They in turn were categorizing the conflict as they knew or read of it. For example, Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

asks for and receives from Perdiccas as Hegemon promotion to Satrap of Egypt. There he disposes of the Nomarch

A nomarch (, Great Chief) was a provincial governor in ancient Egypt; the country was divided into 42 provinces, called Nome (Egypt), nomes (singular , plural ). A nomarch was the government official responsible for a nome.

Etymology

The te ...

of Alexandria appointed by Alexander. Thereafter he refers to himself for the next nearly 20 years as Satrap, even though there was then no empire. Finally in 305, when all hope of empire was gone, he declares himself Pharaoh of Egypt. Meanwhile, he perpetuates the cultural legacy of Alexander, most notably with the museum and library, and the recruitment of population for Alexandria from many different nations. Historians of Ptolemy divide his biography into Ptolemy Satrap and Ptolemy Basileus. Earlier it was Ptolemy Hetairos. The term "Diadochos" was used by the historians to mean any and all of these statuses.

Background

Alexander died on June 11, 323 BC, in the early hours of the morning. He had given his signet ring to his second-in-command, Perdiccas, on the previous day, according to the main account, that ofQuintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus (; ) was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alex ...

, in ''History of Alexander'', which is summarized here. Curtius claims that Alexander predicted his own death, as well as the chaos resulting from it. Modern authorities disagree on whether or not this report is true, but if it is, Alexander's prediction would not have required the gift of clairvoyance and would have been largely stating the obvious; he had been dealing with mutiny among the Macedonian troops since before the expedition to India. At that time he formed a special unit of Persian young men, the Epigoni, to be armed and trained in Macedonian ways. On his return from India he hired them exclusively as his bodyguards. The handful of Macedonian generals officially titled bodyguards he used as senior staff officers. He was covered with old wounds from head to foot. He was seriously ill days before his death.

Council in Babylon

On the day of his death the ''Somatophylakes

''Somatophylakes'' (; singular: ''somatophylax'', σωματοφύλαξ) were the bodyguards of high-ranking people in ancient Greece.

The most famous body of ''somatophylakes'' were those of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. They ...

'' announced a council, to which they invited the main '' Hetairoi'' (officers of the cavalry) and the line officers of the infantry, to be held at the royal quarters. Disobeying orders and ignoring the invitation list, the common soldiers pushed their way in, displacing many officers. Yielding to the inevitable, the ''somatophylakes'' allowed them to stay and to vote at the council. Voting was by voice, except for beating on the shield with the spear, which signified "nay".

Perdiccas opened by exposing (the manner is not stated) Alexander's "chair", from which he rendered official decisions. On it were his diadem, robe, cuirass and signet ring, which he was accustomed to wear when he spoke ''ex cathedra''. At the sight of them the crowd grieved volubly. Perdiccas addressed the grief, saying that the gods had given them Alexander for an appointed time, and now that it was over, they had taken him back. He pointed out their position as conquerors among the conquered. It was vital to their continuance, he said, that they have a "head". Whether it is one or many is in your "power". He thus raised the main issue, the question of "one" or "many". Roxana, Alexander's Bactrian wife, was six months into her pregnancy. He suggested that they choose someone to rule. The floor was open for discussion.

Proposals

Nearchus

Nearchus or Nearchos (; – 300 BC) was one of the Greeks, Greek officers, a navarch, in the army of Alexander the Great. He is known for his celebrated expeditionary voyage starting from the Indus River, through the Persian Gulf and ending at t ...

, the fleet commander, proposed Heracles

Heracles ( ; ), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a Divinity, divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of ZeusApollodorus1.9.16/ref> and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive descent through ...

, the illegitimate son of Alexander by his Persian mistress Barsine, be made king.Green 1990, p. 7. The vote was "nay". Ptolemy took the floor to say that selecting Heracles would be a disgrace (''piget''), because his mothers was a "captive" (''captivi''), and what would be the good of conquest if the conquered ruled the conquerors? Aristonous of Pella proposed the ring be restored to Perdiccas as Alexander’s choice. The vote was "aye". For whatever reason, Perdiccas stood for some time without reply. Then he moved behind the ''somatophylakes''. Curtius is of the opinion that he wished to be begged to take the position. His behavior was taken as a refusal. His enemies took advantage of the opening.

Meleager

In Greek mythology, Meleager (, ) was a hero venerated in his '' temenos'' at Calydon in Aetolia. He was already famed as the host of the Calydonian boar hunt in the epic tradition that was reworked by Homer. Meleager is also mentioned as o ...

saw in the confusion a chance to attack Perdiccas. There was no difference, he said, in voting for either Perdiccas or Heracles, as the former would rule anyway as "guardian" (''tutela''). The implication is that Perdiccas had some sort of legal guardianship of Alexander's children that would automatically apply even if they were voted kings. If the soldiers really were the deciding authority, he said, then why should they not enrich themselves by plundering the treasury? Amidst the uproar he gave the appearance of leading away an armed party to do just that, "the assembly having turned to sedition and discord".

An ordinary soldier saved the day by standing forward to shout that there was no need for civil war when Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother, was the legal heir. They would never find another Alexander. Why should his heir be defrauded of his inheritance? The crowd became suddenly silent, to be followed by a loud positive voice vote. Too late, Peithon began to speak in opposition – Arrhidaeus was mentally disabled – but was shouted down.

Development of factions

The soldiers, though allowed a vote, were not officially part of the council. Peithon proposed that it appoint Perdiccas andLeonnatus

Leonnatus (; 356 BC – 322 BC) was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Gre ...

"Guardians" of Heracles, while Craterus and Antipater

Antipater (; ; 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general, regent and statesman under the successive kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collapse of the Argead house, his son Cassander ...

were to "administer" Europe. The appointments were adopted without consulting Arrhidaeus. Meleager left and returned with Arrhidaeus, shouting for assistance from the soldiers. Two factions had now developed, one for Perdiccas, and one for the Arrhidaeans, supported by Meleager. In the uproar; Arrhidaeus escaped in fear. The crowd called him back, placing Alexander's robe around him. Meleager put on his armor in public view, preparing to defend Arrhidaeus. The soldiers threatened bodily harm to the Bodyguards. They rejoiced that the "empire" would remain in the same family. According to Peter Green, "xenophobia

Xenophobia (from (), 'strange, foreign, or alien', and (), 'fear') is the fear or dislike of anything that is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression that is based on the perception that a conflict exists between an in-gr ...

played its part here: the Macedonian rank and file did not relish the prospect of kowtowing to a half-Oriental monarch."

The party for Meleager collected so many adherents that Perdiccas, "terrified", called for 600 elite troops, "the royal guard of young men"; that is, the unit of Persian Epigoni formed by Alexander to protect him from his men, under Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, and took up a defensive position around the quarters where Alexander's body yet lay. They would not be in favor of a faction that rejected Alexander's children because their mothers were Persian. Military action began. Missiles rained in on the defenders. The situation having gotten out of control, the senior officers with Meleager took off their helmets so that they could be identified and called to Perdiccas to surrender. He had no choice. He put down his arms, followed by the Epigoni putting down theirs.

Meleager commanded them to remain in place while he hunted Perdiccas, but the latter escaped to the Euphrates

The Euphrates ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of West Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia (). Originati ...

River, where he was reinforced by the Hetairoi cavalry under Leonnatus

Leonnatus (; 356 BC – 322 BC) was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Gre ...

. It seems clear, Alexander's most trusted men backed Perdiccas. Meleager sent a commission of assassins to ask Perdiccas to return, with secret orders to kill him if he hesitated. Meeting them with a bodyguard of 16 Epigoni, Perdiccas reviled them as they approached. They returned, having accomplished nothing. The day ended.

War of nerves

The next day, seeing who was not in their party, the soldiers of Meleager's faction had second thoughts. A mutiny developed. Representatives undertook to interrogate Arrhidaeus as to whether he had ordered Perdiccas’ arrest. He said that he did, but that it was at Meleager's instigation. He refused action against Perdiccas. The council that had been called the previous day was officially terminated. They were hoping Perdiccas would dismiss his men, but he did not. Instead he moved against the supply lines, cutting off the supply of grain. He did not dare attack the city, as the odds were overwhelming. Under properly skilled generals, the forces in the city might have sallied out to break the blockade and crush its instigators, but the defenders took no action. Famine began. Holding another council, the Macedonians in the city decided the king should send emissaries to Perdiccas to ask for terms of peace. In terms of forces the opposite should have been true, but Perdiccas knew he had all the generals on his side. Moreover, according to Plutarch in ''Life of Eumenes'', one of the ''Hetairoi'',Eumenes

Eumenes (; ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek general, satrap, and Diadoch, Successor of Alexander the Great. He participated in the Wars of Alexander the Great, serving as Alexander's personal secretary and later on as a battlefield commander. Eume ...

, had remained behind and was trying to convince the soldiers to come to terms. Perdiccas demanded an investigation into what he was calling the sedition and that the leaders should be turned over to him. Even Arrhidaeus could see that he was after Meleager. With tears running down his cheeks Arrhidaeus addressed the assembly, stating that he would give up the throne rather than that any more blood should be shed. He offered the crown to any who should affirm they were qualified to take it. This natural goodness moved the assembly to reaffirm his position. Eumenes managed to sway Meleager's troops to a less belligerent position, proposing a compromise in which Arrhidaeus would be made king, and, if Roxana's child proved to be a son, he should be made joint king with Arrhidaeus.Green 1990, p. 8. According to Curtius, the assembly sacrificed "the old view of the kingship". They sent emissaries to Perdiccas asking to set up a triumvirate of "chiefs": Arrhidaeus, Perdiccas and Meleager. Perdiccas accepted, explains Curtius, hoping to divide Meleager from Arrhidaeus. Arrhidaeus was made king and renamed Philip III, while Alexander's and Roxana's child, who would indeed be a son, would become Alexander IV.

Victory of Perdiccas's faction

Meleager rode out at the head of his forces to enact a truce. As the men came together, Perdiccas’ troops began to complain that they should have to accept Meleager as co-regent. Curtius says that Perdiccas put them up to it. Meleager lost his temper. The two leaders embraced. Meleager complained to Perdiccas of what he had heard. The two agreed to purge the whole army of its divisive elements. The ceremony of reconciliation, based on Macedonian practice, required assembly of both sides under arms in a field between the bowels of a sacrificed dog. The two sides would then proceed to each other and intermingle. Meleager’s infantry in battle array faced the ''Hetairoi'' cavalry enhanced by elephants. The infantry flinched as the cavalry started toward them but stood fast. The king, however, had conferred with Perdiccas about the sedition. As the gap narrowed, he rode up and down the line singling out the leaders who had stood with Meleager against Perdiccas. He was not informed of Perdiccas' intention. As the two sides closed, Perdiccas's men, perhaps the Epigoni, arrested 300 known leaders of sedition, dragging them away for immediate execution, by one account by being trampled by war elephants goaded on for the purpose. Initially Meleager was spared and was appointed Perdiccas's deputy (''hyparchos''), but after the crisis had passed and the situation was again under control, Meleager, who saw them coming for him, took refuge in a temple, where he was murdered. The army meanwhile mingled and the schism was healed.Another council in Babylon

Perdiccas, as ''epimelētēs'' (guardian or regent) and with the authority conferred by Alexander's seal ring, summoned a new council, in the language of ancient legislators, "to which it was pleasing to divide the empire". Most of the great marshals were present, but three were not. Antipater, who had been in charge of Macedonia, was inPella

Pella () is an ancient city located in Central Macedonia, Greece. It served as the capital of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. Currently, it is located 1 km outside the modern town of Pella ...

. Alexander had summoned Antipater to Babylon a few months before his death, but Antipater, suspecting he would be killed if he went, sent his son Cassander

Cassander (; ; 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and '' de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a contemporary of Alexander the ...

instead. Craterus, whom Alexander had appointed to replace Antipater, was on his way to Europe with Polyperchon and ten thousand veterans. They had reached Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

, when they learned of Alexander's death, and decided to stay there until they received further news. Antigonus One-Eye, who was commander of central Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; , ''Phrygía'') was a kingdom in the west-central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River.

Stories of the heroic age of Greek mythology tell of several legendary Ph ...

and responsible for keeping the route to Europe open, stayed where he was, in the fortress at Celaenae.

Nevertheless, the partition took place forthwith, the divisions apparently being negotiated ad hoc, as Ptolemy was able to ask for and received the satrapy of Egypt. "Ptolemy was one of the few to realize that limiting his ambitions would actually get him farther in the long run." Europe had not yet been divided into satrapies. There was no need to replace any eastern satraps. Perdiccas believed he was carrying out Alexander's plans, extending the modified Persian Empire into Greece, western Asia and Africa. He insisted on the supreme authority in the name of the king. Shortly that fiction was to be assaulted, ending in the second of the three partitions, which was an overt one manifestly to all. After the partition the council turned to the business of disposing of Alexander's body, which had lain unburied for seven days. The date of the partition was therefore June 18, 323 BC, or near it.

Ancient sources

Curtius is the main source for the events immediately following the death of Alexander. No one else presents the same depth of detail. For the distribution of satrapies in the partition there are some several sources, not all of equal value. The only complete account isDiodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

's ''Bibliotheca historica

''Bibliotheca historica'' (, ) is a work of Universal history (genre), universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, and describe the h ...

'', which was also the first to be written, c. 40 BC, and should thus be considered the more reliable source.Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca HistoriXVIII, 3

/ref> The Byzantine bishop Photius (c. 820–893) produced an

epitome

An epitome (; , from ἐπιτέμνειν ''epitemnein'' meaning "to cut short") is a summary or miniature form, or an instance that represents a larger reality, also used as a synonym for embodiment. Epitomacy represents "to the degree of." A ...

of 279 books in his ''Bibliotheca'', which contains two relevant (but much abbreviated) accounts. The first is Arrian

Arrian of Nicomedia (; Greek: ''Arrianos''; ; )

was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander, and philosopher of the Roman period.

'' The Anabasis of Alexander'' by Arrian is considered the best source on the campaigns of ...

's ''Continuation'' or ''After Alexander'' (codex 92).ArrianContinuation (codex 92)

/ref> The second is Dexippus's ''History'' of events after Alexander (codex 82),Dexippus

History (codex 82)

/ref> which itself seems to be based on Arrian's account; compare Arrian:

Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, and the country on the shore of the Euxine as far as Trapezus (a Greek colony from Sinope), to Eumeneswith Dexippus:

Eumenes Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, and the shores of the Euxine as far as Trapezus (Trebizond).However, the epitome of Dexippus contains some information which was presumably excerpted from the epitome of Arrian. The final source is

Justin

Justin may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Justin (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Justin (historian), Latin historian who lived under the Roman Empire

* Justin I (c. 450–527) ...

's epitome of Pompeius Trogus's ''Philippic History'', which is probably the latest source and diverges from the other sources, seemingly containing several obvious mistakes.

All the latter sources seem to have read (and to an extent copied) Diodorus, or the most likely source of Diodorus's list, Hieronymus of Cardia

Hieronymus of Cardia (, ) was a Greek general and historian from Cardia in Thrace, and a contemporary of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC).

After the death of Alexander III, he followed the fortunes of his friend and fellow-countryman Eumenes

...

. One passage in particular (see below) is very similarly worded in all accounts, although ironically this same passage contains most of the ambiguities that are to be found.

It is possible there is a copying error in Justin's work; the name of a satrap often occurs adjacent to the satrapy that Diodorus allots them (but not directly associated with it). ''Pelasgia'' does not appear to have been the name of a real Persian or Greek satrapy and the insertion of this word may have shifted the satraps by one place in the list, dislocating them. In addition, Armenia (not mentioned as a satrapy in any other account) may be a mistake for Carmania (which occurs in the same place in Diodorus's list). One possible interpretation of the passage would be: Amyntas was allotted the Bactrians, Scythaeus the Sogdians, Nicanor; the Parthians, Philippus; the Hyrcanians, Phrataphernes;By removing one (apparently meaningless) word and slightly altering the punctuation, five satraps now match the satrapy allotted to them in Diodorus. However, it is clear that the problems with this passage are more extensive, and cannot be easily resolved.the Armenians(the Carmanians), Tleptolemus; the Persians, Peucestes; the Babylonians, Archon;the PelasgiansArcesilaus, Mesopotamia.

Partition

Europe

;Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

, Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

and the rest of Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

:All sources agree that Antipater

Antipater (; ; 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general, regent and statesman under the successive kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collapse of the Argead house, his son Cassander ...

became governor of Macedon and Greece; Arrian adds Epirus to this. Arrian also suggests that this region was shared with Craterus, whereas Dexippus has "the general charge of affairs and the defence of the kingdom was entrusted to Craterus".

;Illyria

In classical and late antiquity, Illyria (; , ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; , ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyrians.

The Ancient Gree ...

:Arrian explicitly includes Illyria within Antipater's remit; Diodorus says that "Macedonia and the adjacent peoples were assigned to Antipater". However, Justin has 'Philo' as governor of Illyria; there is no apparent other mention of Philo in the sources, so it is possible this is a mistake by Justin.

;Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

:All sources agree that Lysimachus became governor of "Thrace and the Chersonese, together with the countries bordering on Thrace as far as Salmydessus on the Euxine".

Asia Minor

;GreaterPhrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; , ''Phrygía'') was a kingdom in the west-central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River.

Stories of the heroic age of Greek mythology tell of several legendary Ph ...

, Lesser/ Hellespontine Phrygia, Cappadocia

Cappadocia (; , from ) is a historical region in Central Anatolia region, Turkey. It is largely in the provinces of Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde. Today, the touristic Cappadocia Region is located in Nevşehir ...

and Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; , modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; ) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus to the east, and separated from Phrygia (later, Galatia ...

, Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

and Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

:All sources agree on the distribution of these satrapies to, respectively, Antigonus, Leonnatus

Leonnatus (; 356 BC – 322 BC) was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Gre ...

, Eumenes of Cardia, Menander

Menander (; ; c. 342/341 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek scriptwriter and the best-known representative of Athenian Ancient Greek comedy, New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His record at the Cit ...

and Philotas.

;Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

:Diodorus has Asander

Asander or Asandros (; lived 4th century BC) was the son of Philotas (father of Parmenion), Philotas and brother of Parmenion and Agathon (son of Philotas), Agathon. He was a Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian general under Alexander the Great, a ...

as satrap, but Arrian and Justin have Cassander

Cassander (; ; 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and '' de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a contemporary of Alexander the ...

. Since Asander was definitely satrap of Caria after the Partition of Triparadisus, it is possible that both Arrian and Justin have mistaken Asander for the better-known Cassander (or that the name has changed during later copying/translation etc.).

;Lycia

Lycia (; Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; , ; ) was a historical region in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğ ...

and Pamphylia

Pamphylia (; , ''Pamphylía'' ) was a region in the south of Anatolia, Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (all in modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the ...

:Both Diodorus and Arrian have Antigonus receiving these satrapies in addition to Greater Phrygia, whereas Justin has Nearchus

Nearchus or Nearchos (; – 300 BC) was one of the Greeks, Greek officers, a navarch, in the army of Alexander the Great. He is known for his celebrated expeditionary voyage starting from the Indus River, through the Persian Gulf and ending at t ...

receiving both of them. This is possibly another mistake by Justin; Nearchus was satrap of Lycia and Pamphylia from 334 to 328 BC.

North Africa

;Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

:All sources agree that these regions ("Egypt and Libya, and of that part of Arabia that borders upon Egypt") were given to Ptolemy, son of Lagus.

Western Asia

;Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

:All sources agree that these regions were given to Laomedon of Mytilene and Arcesilaus

Arcesilaus (; ; 316/5–241/0 BC) was a Greece, Greek Hellenistic philosophy, Hellenistic philosopher. He was the founder of Academic Skepticism and what is variously called the Second or Middle or New Academy – the phase of the Platonic Acade ...

respectively.

The next satrapies moving eastward are much more problematic, with Justins's account widely diverging from both Diodorus and Arrian/Dexippus. The following passage is the source of most of these differences:

The Arachosians and Gedrosians were assigned to Sibyrtius; the Drancae and Arci to Stasanor. Amyntas was allotted the Bactrians, Scythaeus the Sogdians, Nicanor the Parthians, Philippus the Hyrcanians, Phrataphernes the Armenians, Tlepolemus the Persians, Peucestes the Babylonians, Archon the Pelasgians, Arcesilaus, Mesopotamia.This passage seems to be directly derived from Diodorus, listing the satrapies in more-or-less the same order, cf.

He gave Arachosia and Cedrosia to Sibyrtius, Aria and Dranginê to Stasanor of Soli, Bactrianê and Sogdianê to Philip, Parthia and Hyrcania to Phrataphernes, Persia to Peucestes, Carmania to Tlepolemus, Media to Atropates, Babylonia to Archon, and Mesopotamia to Arcesilaüs.Pelasgia does not appear in any other accounts, and does not seem to have been a real satrapy; it is possible that the insertion of this word has caused some of the satraps to shift by one place in the interpretation of Justin's passage. Note 1 In addition, Armenia, also not mentioned in any other accounts as a satrapy may be a mistake for Carmania (which appears in the same position in Diodorus's list). The equivalent passage is missing from Arrian, although it does appear in Dexippus – albeit with its own mistakes:

Siburtius ruled the Arachosians and Gedrosians; Stasanor of Soli the Arei and Drangi; Philip the Sogdiani; Radaphernes the Hyrcanians; Neoptolemus the Carmanians; Peucestes the Persians ... Babylon was given to Seleucus, Mesopotamia to Archelaus.Radaphernes is presumably Phrataphernes, and Dexippus has possibly confused Tlepolemus (clearly named by Arrian, Justin and Diodorus) with Neoptolemus (another of Alexander's generals). It is well established that Seleucus only became satrap of Babylonia at the second partition (the Partition of Triparadisus), so Dexippus may have mixed up the two partitions at this point. ;

Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

:Since Diodorus is the more reliable text, and there seem to be mistakes here in both Justin and Dexippus, the probability is that Archon of Pella was satrap of Babylonia.

;Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

:Since Diodorus and Dexippus both agree on Peucestas being satrap of Persia, this is probably the case.

; Carmania

:Tlepolemus was definitely satrap of Carmania after the second partition, and Diodorus places him as satrap at the first partition, so this was probably the case.

;Hyrcania

Hyrcania (; ''Hyrkanía'', Old Persian: 𐎺𐎼𐎣𐎠𐎴 ''Varkâna'',Lendering (1996) Middle Persian: 𐭢𐭥𐭫𐭢𐭠𐭭 ''Gurgān'', Akkadian: ''Urqananu'') is a historical region composed of the land south-east of the Caspian Sea ...

and Parthia

Parthia ( ''Parθava''; ''Parθaw''; ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemeni ...

:Diodorus allots these regions to Phrataphernes, and Dexippus also has (Ph)rataphernes as satrap of Hyrcania, so it was probably the case that these two adjacent regions were governed by this native Persian. Phrataphernes had been satrap of these regions during Alexander's lifetime,Arrian, Anabasis AlexandrIV, 23

and therefore his retention of these satrapies corresponds with Arrian's statement that: "At the same time several provinces remained under their native rulers, according to the arrangement made by Alexander, and were not affected by the distribution." ;Lesser

Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

:All sources agree that this was given to Atropates, who was also a native Persian, and satrap of Media under Alexander.Arrian, Anabasis AlexandrVII, 4

;Greater

Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

:Diodorus and Dexippus allot this to Peithon. Justin says that: "Atropatus was set over the Greater Media; the father-in-law of Perdiccas over the Less(er)". However, Atropates ''was'' the father-in-law of Perdiccas, so Justin is clearly confused on this point. Since Peithon was definitely satrap of Greater Media after the second partition, it is likely he also was at the first.

; Susiana

:Neither Diodorus nor Arrian/Dexippus mention Susiana at the first partition, but both mention it at the second partition; it was therefore a real satrapy. Only Justin gives a name, Scynus, for this satrapy at the first partition, but this person is not apparently mentioned elsewhere.

Central Asia

;Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian language, Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area ...

and Sogdiana

:Diodorus has Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

as satrap of both these regions; Dexippus also has Philip as Satrap of Sogdiana, but does not mention Bactria. Justin, however, names Amyntas and Scytheaus as satraps of Bactria and Sogdiana. This is the most problematic part of Justin's account, which is clearly completely at variance with the other accounts. Amyntas and Scythaeus are not apparent in other records of the period, and their presence here is not easy to explain.

; Drangiana and Aria

In music, an aria (, ; : , ; ''arias'' in common usage; diminutive form: arietta, ; : ariette; in English simply air (music), air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrument (music), instrumental or orchestral accompan ...

, Arachosia and Gedrosia

Gedrosia (; , ) is the Hellenization, Hellenized name of the part of coastal Balochistan that roughly corresponds to today's Makran. In books about Alexander the Great and his Diadochi, successors, the area referred to as Gedrosia runs from the I ...

:All accounts are consistent in naming Stasanor and Sibyrtius as respective satraps of these two double satrapies.

; Paropamisia

:Diodorus and Dexippus both have Alexander's father-in-law Oxyartes, a native Bactrian, as ruler of this region. Justin has "Extarches" which is presumably a corrupted version of Oxyartes. Oxyartes was another native ruler left in the position to which Alexander appointed him.

Indian subcontinent

;Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans- Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northwest through the dis ...

and Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

:Diodorus and Dexippus name King Porus, Porus and Taxiles as satraps of these regions respectively; these are two more native rulers left in the position given to them by Alexander. Justin concurs with Taxiles in Punjab, and does not mention Indus.

;Other Indian Colonies

:All sources agree that another Peithon, son of Agenor, Peithon, the son of Agenor was ruler of the rest of the Indian territory not given to Taxiles and Porus. Exactly where this was is somewhat uncertain. Diodorus describes it as: "To Pithon he gave the satrapy next to Taxiles and the other kings" whereas Dexippus has: "Porus and Taxilus were rulers of India, to Porus being allotted the country between the Indus and the Hydaspes, the rest to Taxilus. Pithon received the country of the neighbouring peoples, except the Paramisades", and Justin says: "To the colonies settled in India, Python, the son of Agenor, was sent."

Summary table, Babylon and Triparadisus

Notes

Bibliography

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Partition Of Babylon 323 BC 4th-century BC treaties Military history of Babylon Hellenistic dynasties, Partition (politics) Treaties of the Diadochi, Babylon Seleucus I Nicator Ptolemy I Soter