Paraophthalmosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Nannopterygius'' (meaning "small wing/flipper" in Greek) is an

''Nannopterygius'' was small for an ichthyosaur, measuring up to long at maximum. About of this was

''Nannopterygius'' was small for an ichthyosaur, measuring up to long at maximum. About of this was

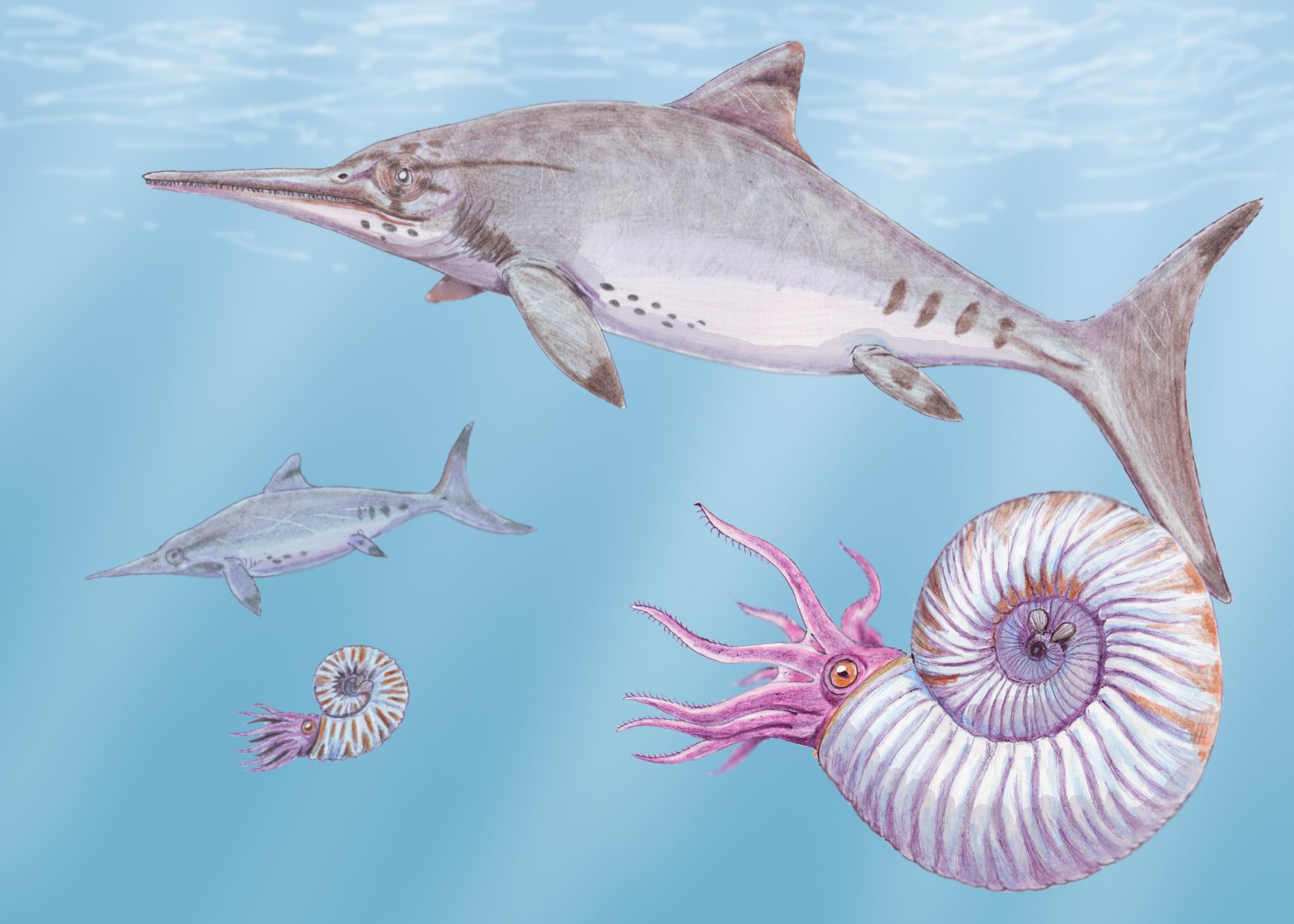

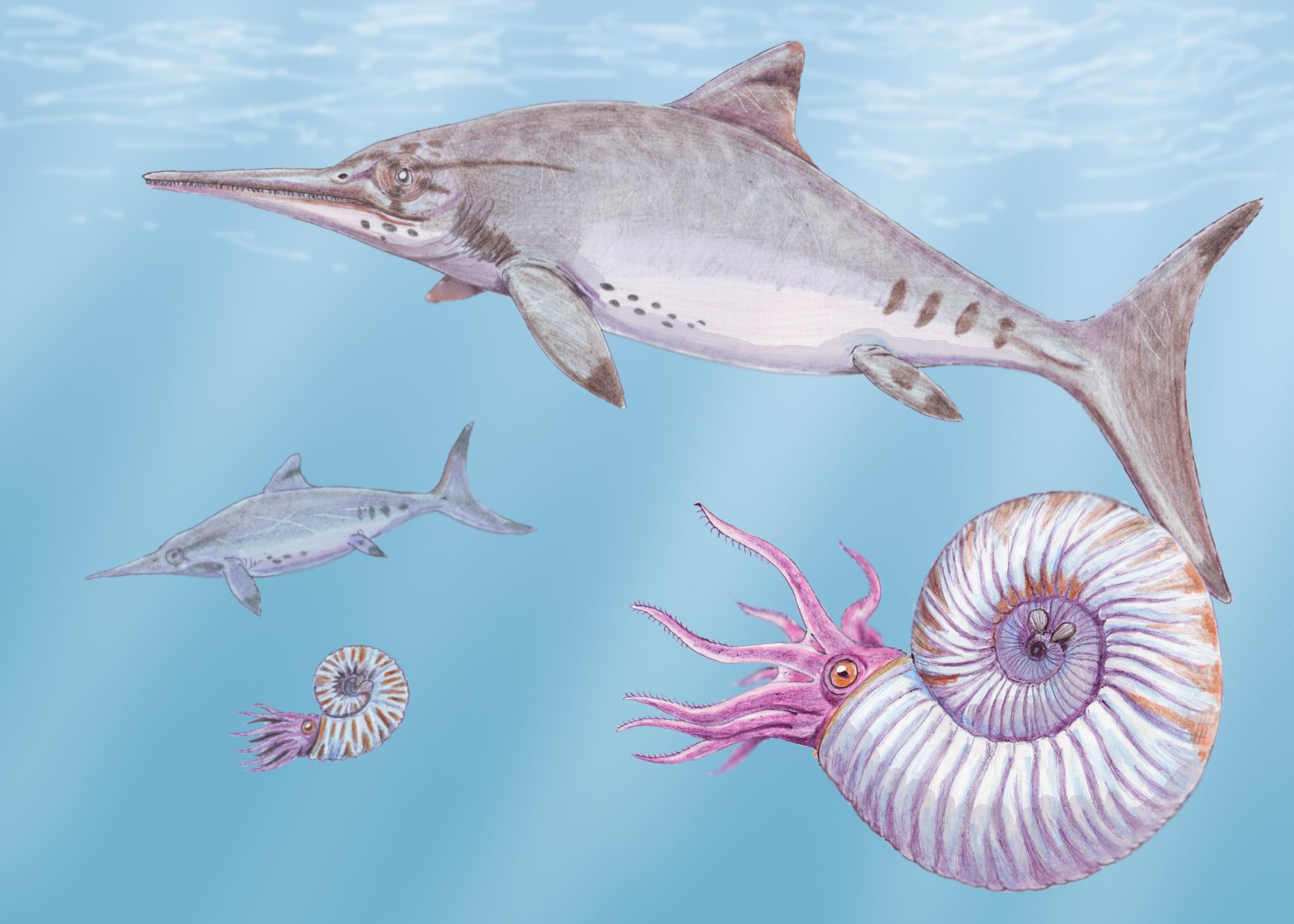

The type species is known from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation in Dorset, England. The Kimmeridge Clay hosts a wealth of marine fossils dating to the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic, many of which are incredibly well preserved, however unfortunately very little has been published. At the time, Europe represented an island archipelago which was closer to the equator than it is today, surrounded by warm, tropical seas. The Kimmeridge Clay specifically represents an offshore marine environment, in which the seafloor was far enough below the surface not to be disturbed by storms. It was home to a great variety of marine life, including many cephalopods, fishes such as ''

The type species is known from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation in Dorset, England. The Kimmeridge Clay hosts a wealth of marine fossils dating to the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic, many of which are incredibly well preserved, however unfortunately very little has been published. At the time, Europe represented an island archipelago which was closer to the equator than it is today, surrounded by warm, tropical seas. The Kimmeridge Clay specifically represents an offshore marine environment, in which the seafloor was far enough below the surface not to be disturbed by storms. It was home to a great variety of marine life, including many cephalopods, fishes such as ''

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of ophthalmosaurid

Ophthalmosauridae is an extinct family of thunnosaur ichthyosaurs from the Middle Jurassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Bajocian - Cenomanian) worldwide. Almost all ichthyosaurs from the Middle Jurassic onwards belong to the family, until the e ...

ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

that lived during the Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period (geology), Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 161.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relativel ...

to the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name) is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 143.1 ...

(Callovian

In the geologic timescale, the Callovian is an age and stage in the Middle Jurassic, lasting between 165.3 ± 1.1 Ma (million years ago) and 161.5 ± 1.0 Ma. It is the last stage of the Middle Jurassic, following the Bathonian and preceding the ...

to Berriasian

In the geological timescale, the Berriasian is an age/ stage of the Early/Lower Cretaceous. It is the oldest subdivision in the entire Cretaceous. It has been taken to span the time between 143.1 ±0.6 Ma and 137.05 ± 0.2 (million years ago) ...

stages). Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s are known from England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

McGowan, C. & Motani, R. (2003). ''Ichthyopterygia

Ichthyopterygia ("fish flippers") was a designation introduced by Richard Owen, Sir Richard Owen in 1840 to designate the Jurassic ichthyosaurs that were known at the time, but the term is now used more often for both true Ichthyosauria and their ...

''. ''In'' Sues, H.-D. Handbook of Paleoherpetology, vol. 8. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, Munich, 175 pp., 19pls. and six species are currently assigned to the genus.

Description

''Nannopterygius'' was small for an ichthyosaur, measuring up to long at maximum. About of this was

''Nannopterygius'' was small for an ichthyosaur, measuring up to long at maximum. About of this was tail

The tail is the elongated section at the rear end of a bilaterian animal's body; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage extending backwards from the midline of the torso. In vertebrate animals that evolution, evolved to los ...

, including a deeply forked and probably homocercal

Fins are moving appendages protruding from the body of fish that interact with water to generate thrust and help the fish swim. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fish fins have no direct connection with the back bone and are supported only by ...

caudal fin

Fins are moving appendages protruding from the body of fish that interact with water to generate thrust and help the fish swim. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fish fins have no direct connection with the back bone and are supported only ...

. The head is long, with a typical long narrow rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

. The eyes

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

are large, hence its classification as an ophthalmosaurid, and have a bony sclerotic ring

The scleral ring or sclerotic ring is a hardened ring of plates, often derived from bone, that is found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates. Some species of mammals, amphibians, and crocodilians lack scleral rings. The rin ...

inside the eye socket. There are at least 60 disc-shaped vertebrae

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

, although owing to the condition of the fossil it is not possible to tell exactly how many there were, showing that ''Nannopterygius'' was flexible, agile and probably a fast swimmer. The ribs

The rib cage or thoracic cage is an endoskeletal enclosure in the thorax of most vertebrates that comprises the ribs, vertebral column and sternum, which protect the vital organs of the thoracic cavity, such as the heart, lungs and great vessels ...

are long and curved, but do not quite join up. Most of the features are very similar to the close relative ''Ophthalmosaurus

''Ophthalmosaurus'' (Greek ὀφθάλμος ''ophthalmos'' 'eye' and σαῦρος ''sauros'' 'lizard') is a genus of ichthyosaur known from the Middle-Late Jurassic. Possible remains from the earliest Cretaceous, around 145 million years ago, a ...

.'' However, its paddles are much smaller, around for the forepaddles and only for the hindpaddles. This gave it a very streamlined

Streamlines, streaklines and pathlines are field lines in a fluid flow.

They differ only when the flow changes with time, that is, when the flow is not steady flow, steady.

Considering a velocity vector field in three-dimensional space in the f ...

, torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

-shaped look, but would have made it quite difficult to generate much lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

or to turn quickly, making it an inefficient long-distance swimmer but speedy over short distances. It is therefore possible that it was an ambush predator

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture their prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey u ...

which plunged into shoals of fish quickly in the shallow seas where it lived.

Discovery and Classification

The first specimen was found in the KimmeridgianKimmeridge Clay Formation

The Kimmeridge Clay is a sedimentary rock, sedimentary deposit of fossiliferous marine clay which is of Late Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous age and occurs in southern and eastern England and in the North Sea. This rock formation (geology), form ...

of Kimmeridge Bay, Dorset, UK and described by Hulke in 1871, who named it ''Ichthyosaurus enthekiodon''.Hulke, J. W. Note on an ''Ichthyosaurus'' (''I. enthekiodon'') from Kimmeridge Bay, Dorset. ''Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society'', 27, 440–441, pl. 17. This referred to its teeth being 'sheathed' in cementum

Cementum is a specialized calcified substance covering the root of a tooth. The cementum is the part of the periodontium that attaches the teeth to the alveolar bone by anchoring the periodontal ligament.

Structure

The cells of cementum are ...

and less likely to fall out than those of other ichthyosaurs. A year earlier, Hulke had described some remains from the same horizon and locality that he thought were ichthyosaurian, naming them ''Enthekiodon'' (no species given).Hulke, J. W. Note on some teeth associated with two fragments of a jaw from Kimmeridge Bay. ''Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society'', 26, 172–174. These are now lost, but Hulke considered them sufficiently similar to demote the name to species level. In 1922, Friedrich von Huene

Baron Friedrich Richard von Hoyningen-Huene (22 March 1875 – 4 April 1969) was a German nobleman paleontologist who described a large number of dinosaurs, more than anyone else in 20th-century Europe. He studied a range of Permo-Carbonife ...

separated this species into the new genus ''Nannopterygius'', named for the small fore- and hindpaddles.Huene, F. F. von 1922. ''Die Ichthyosaurier des Lias und ihre Zusammenhänge''. Verlag von Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin, 114 pp., 22 pls. The first fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

is the most complete, but is flattened. All subsequent fossils are fragmentary. In 2020, several more species, including ''N. borealis'', and the species once contained in the genera ''Paraophthalmosaurus'' and ''Yasykovia'' were named based on remains found in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. The existence of two more species from Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, ''N. mikhailovi'' and ''N. yakimenkae'', was confirmed by Yakupova & Akhmedenov (2022).

The following cladogram shows a possible phylogenetic position of ''Nannopterygius'', which was found to be the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to '' Thalassodraco'', in Ophthalmosauria according to an analysis performed by Zverkov and Jacobs (2020).

Paleoecology

The type species is known from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation in Dorset, England. The Kimmeridge Clay hosts a wealth of marine fossils dating to the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic, many of which are incredibly well preserved, however unfortunately very little has been published. At the time, Europe represented an island archipelago which was closer to the equator than it is today, surrounded by warm, tropical seas. The Kimmeridge Clay specifically represents an offshore marine environment, in which the seafloor was far enough below the surface not to be disturbed by storms. It was home to a great variety of marine life, including many cephalopods, fishes such as ''

The type species is known from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation in Dorset, England. The Kimmeridge Clay hosts a wealth of marine fossils dating to the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic, many of which are incredibly well preserved, however unfortunately very little has been published. At the time, Europe represented an island archipelago which was closer to the equator than it is today, surrounded by warm, tropical seas. The Kimmeridge Clay specifically represents an offshore marine environment, in which the seafloor was far enough below the surface not to be disturbed by storms. It was home to a great variety of marine life, including many cephalopods, fishes such as ''Thrissops

''Thrissops'' (from , 'hair' and 'look') is an extinct genus of stem-teleost fish from the Jurassic period (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian). Its fossils are known from the Solnhofen Limestone, as well as the Kimmeridge Clay.

''Thrissops'' was a fa ...

'' and the early ray ''Kimmerobatis

''Kimmerobatis'' (meaning "Kimmeridge ray") is an extinct genus of spathobatid rays from the Late Jurassic (Tithonian age) Kimmeridge Clay Formation of England. The genus contains a single species, ''K. etchesi'', known from two partial, well- ...

'', and remains of occasional dinosaurs like ''Dacentrurus

''Dacentrurus'' (meaning "tail full of points"), originally known as ''Omosaurus'', is a genus of Stegosauria, stegosaurian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic and perhaps Early Cretaceous (154 - 140 mya (unit), mya) of Europe.

Its type species, ''Om ...

'' which had been washed out to sea. It is most famous for diversity of marine reptiles, such as the metriorhynchid

Metriorhynchidae is an extinct family of specialized, aquatic metriorhynchoid crocodyliforms from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous period (Bajocian to early Aptian) of Europe, North America and South America. The name Metriorhynchidae ...

s ''Metriorhynchus

''Metriorhynchus'' is an extinct genus of marine crocodyliform that lived in the oceans during the Late Jurassic. The type species, ''M. brevirostris'' was named in 1829 as a species of ''Steneosaurus'' before being named as a separate genus by ...

'' and '' Plesiosuchus'', the plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

s ''Colymbosaurus

''Colymbosaurus'' is a genus of cryptoclidid plesiosaur from the Late Jurassic (Callovian-Tithonian) of the UK and Svalbard, Norway. There are two currently recognized species, ''C. megadeirus'' and ''C. svalbardensis''.

Taxonomy

The first re ...

'' and ''Kimmerosaurus

''Kimmerosaurus'' ("lizard from Kimmeridge") is an extinct genus of plesiosaur from the family Cryptoclididae. It is known from remains found in England and Norway.

Discovery

There are very few fossil remains of ''Kimmerosaurus'' known. In fa ...

'', and the ichthyosaurs '' Grendelius'' and ''Thalassodraco''. The apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator or superpredator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the hig ...

s of the Kimmeridge ecosystem would have been the several species of the pliosaurid

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages). The family is more inclusive than the archetypal short-necked large headed species that are placed in ...

''Pliosaurus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages) of Europe and South America. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent ...

'' which have been recovered there, as well as large metriorhynchids like ''Plesiosuchus''. Additionally, the pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s ''Cuspicephalus

''Cuspicephalus'' is an extinct genus of monofenestratan pterosaur known from Dorset in England. Its fossil remains date back to the Late Jurassic period.

Discovery

''Cuspicephalus'' is known from the holotype MJML K1918, a partial skull ...

'' and ''Rhamphorhynchus

''Rhamphorhynchus'' (, from Ancient Greek ''rhamphos'' meaning "beak" and ''rhynchus'' meaning "snout") is a genus of long-tailed pterosaurs in the Jurassic period. Less specialized than contemporary, short-tailed pterodactyloid pterosaurs such ...

'' are also known from the Kimmeridge Clay.

The species ''N. yasykovi'' and ''N. saveljeviensis'' are known from the Volga region of Russia, which gives the Volgian stage its name. Though very little is known or published about the fossils of these localities, fossils of a number of marine animals have been recovered, including several species of the ichthyosaurs ''Arthropterygius'', ''Grendelius'', and ''Undorosaurus''. In addition, fossils of the pliosaurid ''Pliosaurus rossicus'' and indeterminate remains belonging to a metriorhynchid, as well as a high diversity of ammonites including the large-bodied taxon ''Titanites

''Titanites'' is an extinct ammonite cephalopod genus within the Family (biology), family Dorsoplanitidae, that lived during the late Tithonian of the Late Jurassic. Its fossils have been found in Canada and the United Kingdom.

Description

Spec ...

'', are also known from the Volgian-aged sediments of this region.N. G. Zverkov, M. S. Arkhangelsky and I. M. Stenshin (2015) A review of Russian Upper Jurassic ichthyosaurs with an intermedium/humeral contact. Reassessing Grendelius McGowan, 1976. Proceedings of the Zoological Institute 318(4): 558-588

Additionally, the species ''N. borealis'' is known from earliest Cretaceous sediments of the Slottsmøya Member of the Agardhfjellet Formation

The Agardhfjellet Formation is a Formation (geology), geologic formation in Svalbard, Norway. It preserves fossils dating back to the Oxfordian (stage), Oxfordian to Berriasian stages, spanning the Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous boundary. The for ...

. The Slottsmøya Member consists of a mix of shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

s and siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.

Although its permeabil ...

s and was deposited in a shallow water methane seep environment. The seafloor, which was located about below the surface, seems to have been relatively dysoxic, or oxygen-poor, although it was periodically oxygenated by clastic sediments. Despite this, near the top of the member, various diverse assemblages of invertebrates associated with cold seeps have been discovered; these include ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

s like ''Lytoceras

''Lytoceras'' is an ammonite genus that was extant during most of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, and is the type genus for the family Lytoceratidae. These cephalopods were fast-moving nektonic carnivores.

Description

Shells of ''Lytoceras ...

'' and '' Phylloceras'', lingulate brachiopods, bivalves

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified exoskeleton consis ...

like '' Myophorella'' and '' Laevitrigonia'', rhynchonellate brachiopods, tubeworms, belemnoids

Belemnoids are an extinct group of marine cephalopod, very similar in many ways to the modern squid. Like them, the belemnoids possessed an ink sac, but, unlike the squid, they possessed ten Cephalopod arm, arms of roughly equal length, and no t ...

, tusk shell

Scaphopoda (plural scaphopods , from Ancient Greek σκᾰ́φης ''skáphē'' "boat" and πούς ''poús'' "foot"), whose members are also known as tusk shells or tooth shells, are a class (biology), class of shelled Marine life, marine inve ...

s, sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s like ''Peronidella

''Peronidella'' is an extinct genus of Calcareous sponges found in marine sedimentary rocks dated between the Devonian and the Cretaceous periods.Imanov. M., Hrdlickova., S., and Gregorova., R., (2005), ''The Complete Encyclopedia of Fossils' ...

'', crinoid

Crinoids are marine invertebrates that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that remain attached to the sea floor by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms, called feather stars or comatulids, are ...

s, sea urchin

Sea urchins or urchins () are echinoderms in the class (biology), class Echinoidea. About 950 species live on the seabed, inhabiting all oceans and depth zones from the intertidal zone to deep seas of . They typically have a globular body cove ...

s like ''Hemicidaris

''Hemicidaris'' is an extinct genus of echinoids that lived from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous. Its remains have been found in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Sources

* ''Fossils'' (Smithsonian Handbooks) by David Ward (Page 178)

Exte ...

'', brittle star

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids (; ; referring to the serpent-like arms of the brittle star) are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomot ...

s, starfish

Starfish or sea stars are Star polygon, star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class (biology), class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to brittle star, ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to ...

like '' Pentasteria'', crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s like ''Eryma

''Eryma'' is a genus of fossil lobster-like crustaceans, containing 44 species. The oldest known species was discovered in non-marine deposits from the late Triassic Chinle Formation located in the Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. Two oth ...

'', and gastropods

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and from the land. Ther ...

, numbering 54 taxa in total. Though direct evidence from Slottsmøya is currently lacking, the high latitude of this site and relatively cool global climate of the Tithonian mean that sea ice was likely present at least in the winter. In addition to ''Nannopterygius'', the Slottsmøya Member presents a diverse assemblage of other marine reptiles, including the ichthyosaurs ''Undorosaurus gorodischensis'', several species belonging to the genus ''Arthropterygius'', and a partial skull attributed to ''Brachypterygius sp.'' The presence of these taxa indicates that there was significant faunal exchange across the seas of Northern Europe during this time period. Additionally, 21 plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

ian specimens are also known from the site, including two belonging to the large pliosaur ''Pliosaurus funkei'', three to '' Colymbosaurus svalbardensis'', one to '' Djupedalia engeri'', one to ''Ophthalmothule cryostea

''Ophthalmothule'' (meaning "eye of the north"), was a Cryptoclididae, cryptoclidid Plesiosauria, plesiosaur dating to the latest Volgian (around the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary), found in the Slottsmøya Member Lagerstätte of the Agardhfjellet ...

'', and one each to '' Spitrasaurus wensaasi'' and '' S. larseni''. Many of these specimens are preserved in three dimensions and partially in articulation; this is correlated with high abundance of organic elements in the sediments they were buried in.

See also

*List of ichthyosaurs

This list of ichthyosauromorphs is a comprehensive listing of all Genus, genera that have ever been included in the clade Ichthyosauromorpha, excluding purely vernacular terms. The list includes all commonly accepted genera, but also genera that ar ...

* Timeline of ichthyosaur research

This timeline of ichthyosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the History of paleontology, history of paleontology focused on the ichthyosauromorphs, a group of secondarily aquatic marine reptiles whose later members superficially ...

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q1028280 Fossil taxa described in 1922 Middle Jurassic ichthyosaurs Jurassic reptiles of Europe Late Jurassic ichthyosaurs Ichthyosaurs of Europe Jurassic United Kingdom Fossils of Great Britain Tithonian life Fossils of Svalbard Agardhfjellet Formation Early Cretaceous ichthyosaurs Berriasian life Cretaceous Norway Ophthalmosauridae Ichthyosauromorph genera