Pan-Asian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism) is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian peoples. Various theories and movements of Pan-Asianism have been proposed, particularly from East, South and Southeast Asia. The motive for the movement was in opposition to the values of

Pan-Asianism (also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism) is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian peoples. Various theories and movements of Pan-Asianism have been proposed, particularly from East, South and Southeast Asia. The motive for the movement was in opposition to the values of

The concept of a unified

The concept of a unified  The growing official interest in broader Asian concerns was shown in the establishment of facilities for Indian Studies. In 1899,

The growing official interest in broader Asian concerns was shown in the establishment of facilities for Indian Studies. In 1899,

Since the 2000s, Chinese scholars have a more nuanced view of Pan-Asianism, especially those of the Japanese variety. Historian Wang Ping proposed an evaluation system based on chronology: co-operative Classical Asianism (until 1898), expansive Greater Asianism (until 1928), and the invasive Japanese ‘

Since the 2000s, Chinese scholars have a more nuanced view of Pan-Asianism, especially those of the Japanese variety. Historian Wang Ping proposed an evaluation system based on chronology: co-operative Classical Asianism (until 1898), expansive Greater Asianism (until 1928), and the invasive Japanese ‘

Western imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism foc ...

and colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

, and that Asian values

Asian values is a political ideology that attempts to define elements of society, culture and history common to the nations of Southeast and East Asia, particularly values of commonality and collectivism for social unity and economic good — c ...

were superior to European values.

The concept of Asianism in Japan and China has changed during the early 20th century from a foreign-imposed and negatively received, to a self-referential and embraced concept, according to historian Torsten Weber.

Japanese Pan-Asianism

Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

under Japanese leadership had its roots dating back to the 16th century. For example, Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods and regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: ...

proposed to make China, Korea, and Japan into "one". Moreover, Hideyoshi had further planned to expand into India, the Philippines, and other islands in the Pacific.

Originally, Japanese Pan-Asianism believed that Asians shared a common heritage and must therefore collaborate in defeating their Western colonial masters. However, Japanese Asianism mostly focused on East Asian territories, with occasional references to South East Asia and West Asia.

The first lasting pan-Asianist organisation started in Japan. In 1877, inspired by Ōkubo Toshimichi

Ōkubo Toshimichi (; 26 September 1830 – 14 May 1878) was a Japanese statesman and samurai of the Satsuma Domain who played a central role in the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the Three Great Nobles of the Restoration (維新の� ...

's promise to Chinese premier Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang, Marquess Suyi ( zh, t=李鴻章; also Li Hung-chang; February 15, 1823 – November 7, 1901) was a Chinese statesman, general and diplomat of the late Qing dynasty. He quelled several major rebellions and served in importan ...

to promote Chinese-language schools in Japan as a channel of mutual understanding, a Pan-Asianist body was established in Japan known as Shin'akai (Promoting Asia Society), followed by the more successful Kōakai (Raising Asia Society) in 1880. Both focused on the promotion of mutual understanding through providing language education, setting up schools in Japan for teaching Chinese and Korean languages, as well as branches in Korean and Chinese cities. China's envoys to Japan and Korean reformers held membership, and even two diplomats from the Ottoman Empire. The Society used Classical Chinese as the common language of East Asian Pan-Asianists. Japanese Pan-Asianism before 1895 was characterized by an egalitarian view on relations between China, Korea and Japan; in order to avoid the accusation that Japan sought to 'lead' Asia, the Kōakai changed its name to the "Asia Association."

Pan-Asianist ideologues included Tokichi Tarui (1850–1922) who argued for equal Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

-Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

unionization for cooperative defence against the European powers, and Kentaro Oi (1843–1922) who attempted to push social reforms in Korea and establish a constitutional government in Japan. Pan-Asian thought in Japan was further popularized following the defeat of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

(1904–1905). This sparked interest from Indian poets Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Thakur (; anglicised as Rabindranath Tagore ; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengalis, Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer, and painter of the Bengal Renai ...

and Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo (born Aurobindo Ghose; 15 August 1872 – 5 December 1950) was an Indian Modern yoga gurus, yogi, maharishi, and Indian nationalist. He also edited the newspaper Bande Mataram (publication), ''Bande Mataram''.

Aurobindo st ...

and Chinese politician Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

.

The growing official interest in broader Asian concerns was shown in the establishment of facilities for Indian Studies. In 1899,

The growing official interest in broader Asian concerns was shown in the establishment of facilities for Indian Studies. In 1899, Tokyo Imperial University

The University of Tokyo (, abbreviated as in Japanese and UTokyo in English) is a public university, public research university in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Founded in 1877 as the nation's first modern university by the merger of several Edo peri ...

set up a chair in Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

and Kawi, with a further chair in comparative religion

Comparative religion is the branch of the study of religions with the systematic comparison of the doctrines and practices, themes and impacts (including human migration, migration) of the world's religions. In general the comparative study ...

being set up in 1903. In this environment, a number of Indian student

A student is a person enrolled in a school or other educational institution, or more generally, a person who takes a special interest in a subject.

In the United Kingdom and most The Commonwealth, commonwealth countries, a "student" attends ...

s came to Japan in the early twentieth century, founding the Oriental Youngmen's Association The Oriental Youngmen's Association was founded in Japan in 1900 to facilitate the cultivation of friendship among Japanese, Indian, and other Asian students studying in Japan. It was an early expression of Pan-Asianism

file:Asia satellite orthogr ...

in 1900. Their anti-British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

political activity caused consternation to the Indian Government, following a report in the London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

''Spectator

''Spectator'' or ''The Spectator'' may refer to:

*Spectator sport, a sport that is characterized by the presence of spectators, or watchers, at its matches

*Audience

Publications Canada

* '' The Hamilton Spectator'', a Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, ...

''.

Okakura Kakuzō

, also known as Okakura Tenshin , was a Japanese scholar and art critic who in the era of Meiji Restoration reform promoted a critical appreciation of traditional forms, customs and beliefs. Outside Japan, he is chiefly renowned for '' The Book ...

, a scholar and art critic, also praised the superiority of Asian values upon Japanese victory of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

:

TheIn this, Kakuzō was utilising the Japanese concept of ''sangoku'', which existed inHimalayas The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than list of h ...divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilisations, the Chinese with itscommunism Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...ofConfucius Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ..., and theIndia India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...n with itsindividualism Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...of theVedas FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''. The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig .... But not even the snowy barriers can interrupt for one moment that broad expanse of love for theUltimate Ultimate or Ultimates may refer to: Arts, entertainment, and media Music Albums *Ultimate (Bryan Adams album), ''Ultimate'' (Bryan Adams album) *Ultimate (Jolin Tsai album), ''Ultimate'' (Jolin Tsai album) *Ultimate (Pet Shop Boys album), ''Ult ...and Universal, which is the common thought-inheritance of every Asiatic race, enabling them to produce all the greatreligion Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...s of the world, and distinguishing them from those maritime peoples of theMediterranean The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...and theBaltic Baltic may refer to: Peoples and languages *Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian *Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ..., who love to dwell on theParticular In metaphysics, particulars or individuals are usually contrasted with ''universals''. Universals concern features that can be exemplified by various different particulars. Particulars are often seen as concrete, spatiotemporal entities as opposed ..., and to search out the means, not the end, of life.'

Japanese culture

Japanese culture has changed greatly over the millennia, from the country's prehistoric Jōmon period, to its contemporary modern culture, which absorbs influences from Asia and other regions of the world.

Since the Jomon period, ancestral ...

before the concept of Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

became popularised. ''Sangoku'' literally means the "three countries": ''Honshu

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the list of islands by area, seventh-largest island in the world, and the list of islands by ...

'' (the largest island of Japan), '' Kara'' (China) and ''Tenjiku

Tianzhu () is one of the historical ancient Chinese names for the Indian subcontinent. Tian (天) means heaven, and Zhu (竺) means bamboo in Chinese.

Tianzhu was also referred to as ''Wutianzhu'' (, literal meaning is "Five Indias"), because ...

'' (India).

However, Japanese Pan-Asianism evolved into a more nationalist ideology that prioritized Japan's interests. This was evident by the growth of secret societies such as Black Ocean Society and the Black Dragon Society

The , or the Amur River Society, was a prominent paramilitary, ultranationalist group in Japan.

History

The ''Kokuryūkai'' was founded in 1901 by martial artist Uchida Ryohei as a successor to his mentor Mitsuru Tōyama's '' Gen'yōsha''. ...

, which committed criminal activities to ensure the success of Japanese expansionism. Exceptionally, Ryōhei Uchida (1874–1937), who was a member of the Black Dragon Society, was a Japan-Korea unionist and supported Filipino and Chinese revolutions. In addition, Asian territories were seen as reservoirs of economic resources and outlets for the Emperor's "glory" to be displayed. These were evident in government policies such as the Hakko ichiu and Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a Pan-Asianism, pan-Asian union that the Empire of Japan tried to establish. Initially, it covered Japan (including Korea under Japanese rule, annexed Korea), Manchukuo, and Wang Jingwei regime, China, but as ...

agendas. Even Kakuzō was critical of Japan's expansionism after the Russo-Japanese War, viewing it as no different than Western expansionism. He expected other Asians to call them "embodiments of the White Disaster".

Historian Torsten Weber compares these contradictions to the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

, which opposed European imperialism to foster the unimpeded growth of American imperialism.

Chinese Pan-Asianism

First president of the Republic of ChinaSun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

was a proponent of Pan-Asianism. He said that Asia was the "cradle of the world's oldest civilisation" and that "even the ancient civilisations of the West, of Greece and Rome, had their origins on Asiatic soil." He thought that it was only in recent times that Asians "gradually degenerated and become weak." Sun Yat-sen considered Japan and China to be both members of the "Yellow race" and equally threatened from imperialists, and urged Japan to assist China in repealing the Unequal Treaties. In the Russo-Japanese War, Sun had interpreted the Japanese victory as a victory for Asians; as early as 1913, he had attempted to form a pan-Asian alliance with Japanese Prime Minister Katsura Tarō to counter Anglo-Saxon and French imperialism, which he considered to be the principal threats in the world. For Sun, "Pan-Asianism is based on the principle of the Rule of Right, and justifies the avenging of wrongs done to others." He advocated overthrowing the Western "Rule of Might" and "seeking a civilisation of peace and equality and the emancipation of all races." Sun, despite his consistent praise of Japan as a cultural partner, questioned whether they would follow the path of exploitation like Western powers in the future in his final years.

From a Chinese perspective, Japanese Pan-Asianism was interpreted as a competing ideology to Sinocentrism

Sinocentrism refers to a worldview that China is the cultural, political, or economic center of the world. Sinocentrism was a core concept in various Chinese dynasties. The Chinese considered themselves to be "all-under-Heaven", ruled by the ...

as well as rationalization of Japanese imperialism (cf. Twenty-One Demands

The Twenty-One Demands (; ) was a set of demands made during the World War I, First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister of Japan, Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the Government of the Chinese Republic, government of the Re ...

). Nonetheless, Chinese Pan-Asianism emerged and was equally as self-centered as its Japanese counterpart. Its success was limited by China's political instability and weak international status.

Since the 2000s, Chinese scholars have a more nuanced view of Pan-Asianism, especially those of the Japanese variety. Historian Wang Ping proposed an evaluation system based on chronology: co-operative Classical Asianism (until 1898), expansive Greater Asianism (until 1928), and the invasive Japanese ‘

Since the 2000s, Chinese scholars have a more nuanced view of Pan-Asianism, especially those of the Japanese variety. Historian Wang Ping proposed an evaluation system based on chronology: co-operative Classical Asianism (until 1898), expansive Greater Asianism (until 1928), and the invasive Japanese ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a Pan-Asianism, pan-Asian union that the Empire of Japan tried to establish. Initially, it covered Japan (including Korea under Japanese rule, annexed Korea), Manchukuo, and Wang Jingwei regime, China, but as ...

’ (until 1945).

Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek ( ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian Marxist philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual.

He is the international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, Global Distin ...

stated that China has been following pan-Asianism for over a century. He regarded Chinese thinker Wang Hui as the main promoter of a communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

pan-Asianism. Wang Hui advocated that if social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

is grounded in Asian civilizational traditions, it renders it possible to avoid the Western type of multi-party democracy and enact a social order with much stronger people's participation.

Indian Pan-Asianism

Ties between British India and Japan were pursued by some as a way of pushing against British rule, with revolutionaries such asSubhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose (23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945) was an Indian independence movement, Indian nationalist whose defiance of British raj, British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians, but his wartime alliances with ...

meeting with Japanese leaders, though British intelligence services sought to limit these interactions.

The 1951 founding of the Asian Games

The Asian Games, also known as Asiad, is a continental multi-sport event held every four years for athletes of Asia. The Games were regulated by Asian Games Federation from the 1951 Asian Games, first Games in New Delhi, India in 1951, until ...

, now the second-largest sporting event behind the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

, was partially inspired by a newly independent India's vision for Asian solidarity and the emergence of the post-colonial world order. However, Indian pan-Asianism faded away after the fallout of the 1962 India-China War.

Turkish Pan-Asianism

Pan-Asianism inTurkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

has not yet been fully explored, it is not known how many people hold this ideology and how widespread it is. However, Turks who supported Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and have the Pan-Asianism ideology use a redesigned Turkish flag based on Japan's flag in the Second World War.

Pan-Asianism and Asian values

The idea of "Asian values

Asian values is a political ideology that attempts to define elements of society, culture and history common to the nations of Southeast and East Asia, particularly values of commonality and collectivism for social unity and economic good — c ...

" is somewhat of a resurgence of Pan-Asianism. One foremost enthusiast of the idea was the former Prime Minister of Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, Lee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew (born Harry Lee Kuan Yew; 16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015), often referred to by his initials LKY, was a Singaporean politician who ruled as the first Prime Minister of Singapore from 1959 to 1990. He is widely recognised ...

. In India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, Ram Manohar Lohia dreamed of a united socialist Asia. A number of other Asian political leaders from Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

in the 1910s and 20s to Mahathir Mohamad

Mahathir bin Mohamad (; ; born 10 July 1925) is a Malaysian politician, author and doctor who was respectively the fourth and seventh Prime Minister of Malaysia, prime minister of Malaysia from 1981 to 2003 and from 2018 to 2020. He was the ...

in the 1990s similarly argue that the political models and ideologies of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

lack values and concepts found in Asian societies and philosophies. European values such as individual rights and freedoms would not be suited for Asian societies in this extreme formulation of Pan-Asianism.

See also

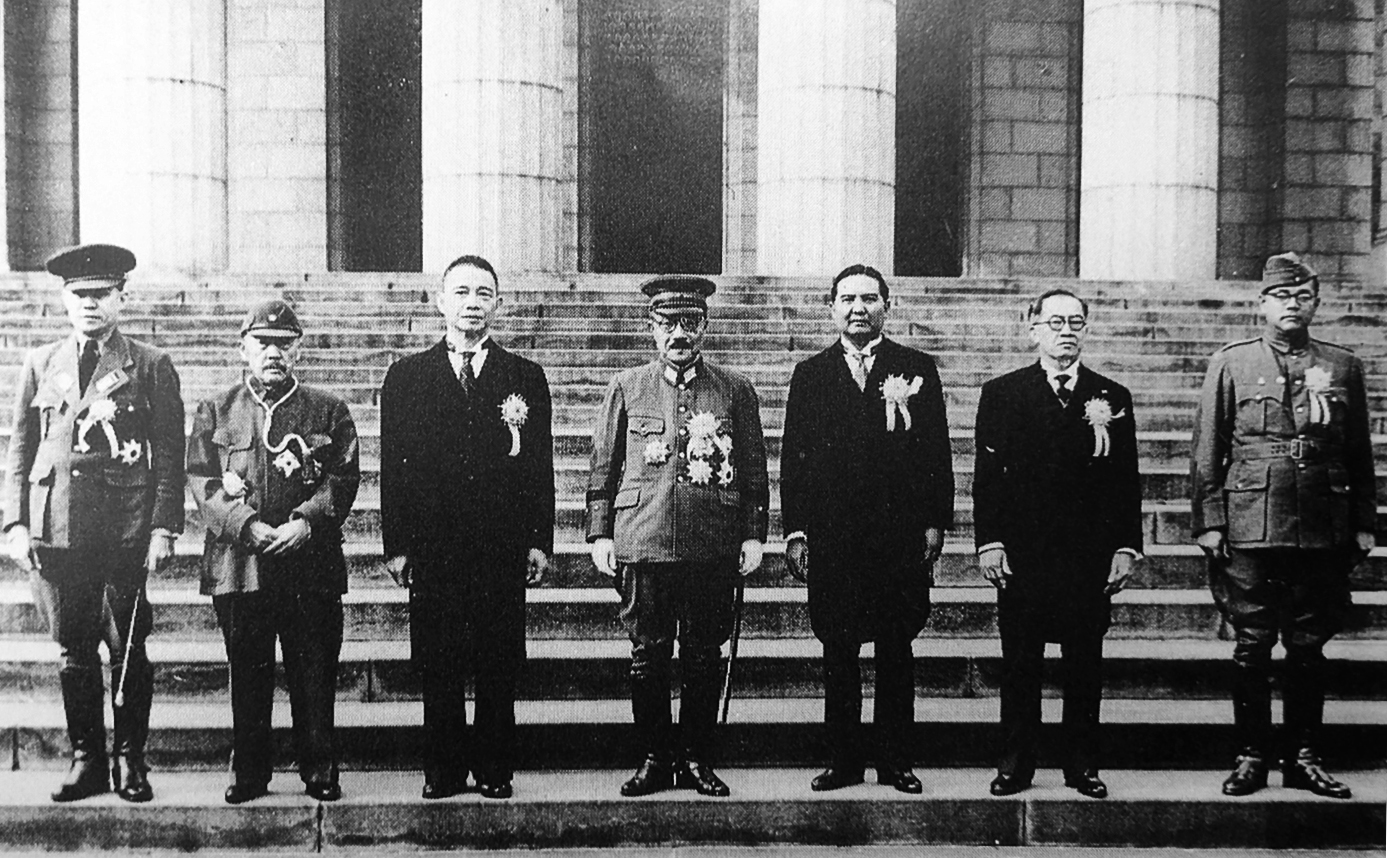

*Greater East Asia Conference

was an international summit held in Tokyo from 5 to 6 November 1943, in which the Empire of Japan hosted leading politicians of various component parts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The event was also referred to as the Tokyo C ...

*Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a Pan-Asianism, pan-Asian union that the Empire of Japan tried to establish. Initially, it covered Japan (including Korea under Japanese rule, annexed Korea), Manchukuo, and Wang Jingwei regime, China, but as ...

* Asiacentrism

*ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations,

commonly abbreviated as ASEAN, is a regional grouping of 10 states in Southeast Asia "that aims to promote economic and security cooperation among its ten members." Together, its member states r ...

(1967 to the present)

* Asia Council

*Asian Development Bank

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is a regional development bank to promote social and economic development in Asia. The bank is headquartered in Metro Manila, Philippines and maintains 31 field offices around the world.

The bank was establishe ...

*Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) is a multilateral development bank and international financial institution that aims to collectively improve economic and social outcomes in Asia. It is the world's second largest multi-lateral d ...

*Asian Relations Conference

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in New Delhi from 23 March to 2 April, 1947. Organized by the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), the Conference was hosted by Jawaharlal Nehru, then the Vice-P ...

* Afro-Asia

**Bandung Conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference (), also known as the Bandung Conference, was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–24 April 1955 in Bandung, We ...

(1955)

*Belt and Road Initiative

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI or B&R), known in China as the One Belt One Road and sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road, is a global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the government of China in 2013 to invest in more t ...

* East Asian Community

*South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is the regional intergovernmental organization and geopolitical union of states in South Asia. Its member states are Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, ...

* Asia Cooperation Dialogue

*Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP ) is a free trade agreement among the Asia-Pacific countries of Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, S ...

*Pan-nationalism

Pan-nationalism () in the social sciences includes forms of nationalism that aim to transcend (overcome, expand) traditional boundaries of basic or historical national identities in order to create a "higher" pan-national (all-inclusive) identit ...

* Fusao Hayashi

* Shumei Okawa

* Iwane Matsui

* Greater Europe, a similar movement in Europe

*Pan-Europeanism

Pan-European identity is the sense of personal identification with Europe, in a cultural or political sense. The concept is discussed in the context of European integration, historically in connection with hypothetical proposals, but since t ...

References

*Bibliography

* Saaler, Sven and J. Victor Koschmann, eds., ''Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History:Colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

, Regionalism and Borders.'' London and New York: Routledge, 2007.

* Saaler, Sven and C.W.A. Szpilman, eds., ''Pan-Asianism: A Documentary History,'' Rowman & Littlefield, 2011. two volumes (1850–1920, 1920–present). (vol. 1), (vol. 2)

*

*

Further reading

* Kamal, Niraj (2002) ''AriseAsia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

: Respond to White Peril.'' New Delhi: Wordsmith .

* Starrs, Roy (2001) ''Asian Nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

in an Age of Globalization

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

.'' London: RoutledgeCurzon .

* Starrs, Roy (2002) ''Nations

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, territory, or societ ...

under Siege: Globalization and Nationalism in Asia.'' New York: Palgrave Macmillan .

*

{{Authority control

World War II propaganda

Colonialism

Nationalist movements in Asia

Far-right politics in Asia

Regionalism (international relations)

Political movements in Asia

Political ideologies

Politics and race

Kokkashugi

Axis powers