The president of the United States (POTUS) is the

head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...

and

head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

of the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. The president directs the

executive branch

The executive branch is the part of government which executes or enforces the law.

Function

The scope of executive power varies greatly depending on the political context in which it emerges, and it can change over time in a given country. In ...

of the

federal government

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

and is the

commander-in-chief of the

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

.

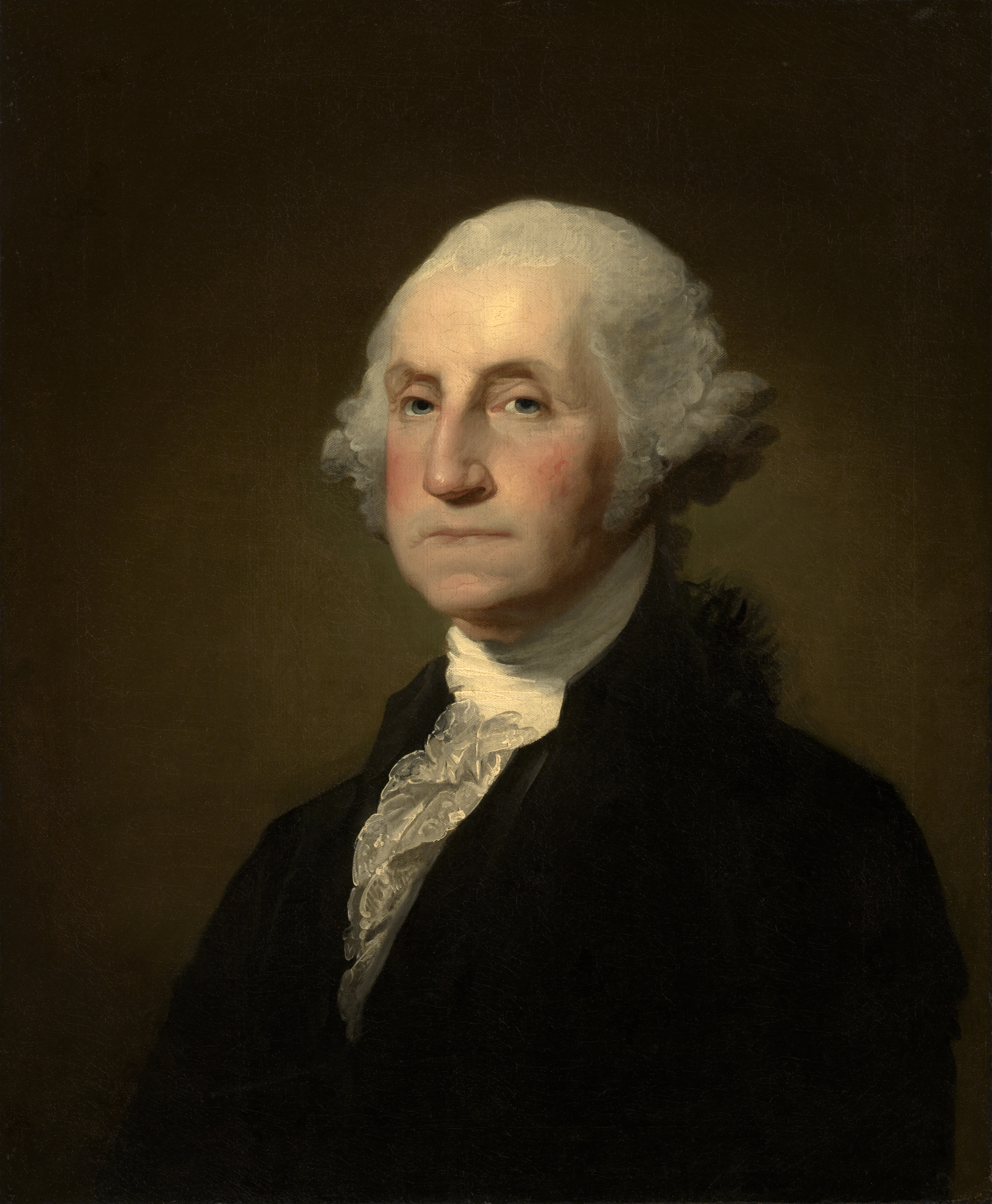

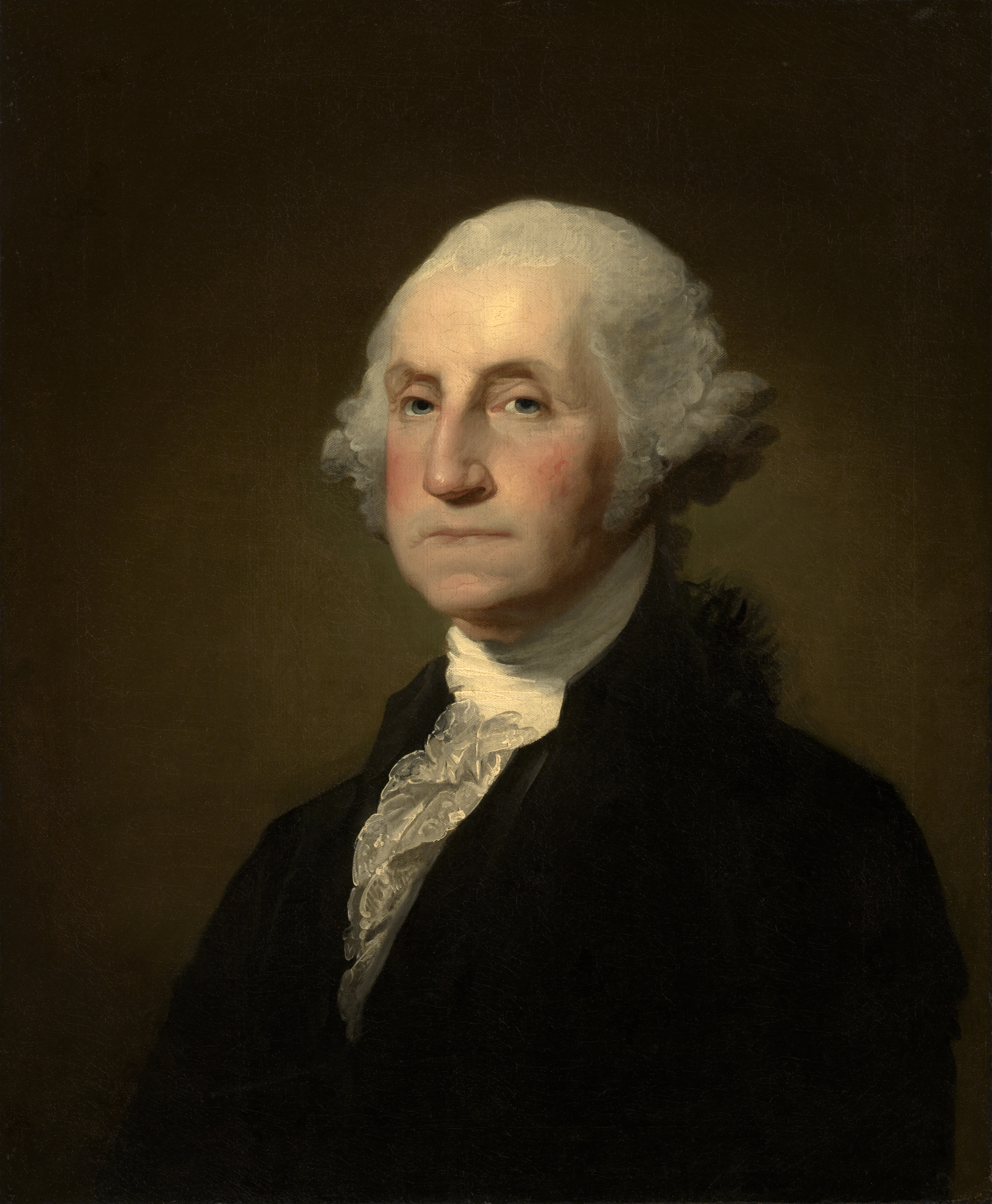

The power of the presidency has grown since the first president,

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, took office in 1789.

While presidential power has ebbed and flowed over time, the presidency has played an increasing role in American political life since the beginning of the 20th century, carrying over into the 21st century with some expansions during the presidencies of

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

and

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

. In modern times, the president is one of the world's most powerful political figures and the leader of the world's only remaining

superpower

Superpower describes a sovereign state or supranational union that holds a dominant position characterized by the ability to Sphere of influence, exert influence and Power projection, project power on a global scale. This is done through the comb ...

. As the leader of the nation with the

largest economy by nominal GDP, the president possesses significant domestic and international

hard and

soft power

In politics (and particularly in international politics), soft power is the ability to co-option, co-opt rather than coerce (in contrast with hard power). It involves shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction. Soft power is ...

. For much of the 20th century, especially during the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, the U.S. president was often called "the leader of the free world".

Article II of the Constitution establishes the executive branch of the federal government and vests executive power in the president. The power includes the execution and enforcement of federal law and the responsibility to appoint federal executive, diplomatic, regulatory, and judicial officers. Based on constitutional provisions empowering the president to appoint and receive ambassadors and conclude treaties with foreign powers, and on subsequent laws enacted by Congress, the modern presidency has primary responsibility for conducting U.S. foreign policy. The role includes responsibility for directing the world's

most expensive military, which has the

second-largest nuclear arsenal.

The president also plays a leading role in federal legislation and domestic policymaking. As part of the system of

separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

,

Article I, Section7 of the Constitution gives the president the power to sign or

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

federal legislation. Since modern presidents are typically viewed as leaders of their political parties, major policymaking is significantly shaped by the outcome of presidential elections, with presidents taking an active role in promoting their policy priorities to members of Congress who are often electorally dependent on the president. In recent decades, presidents have also made increasing use of

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

s, agency regulations, and judicial appointments to shape domestic policy.

The president is

elected indirectly through the

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

to a four-year term, along with the

vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

. Under the

Twenty-second Amendment

The Twenty-second Amendment (Amendment XXII) to the United States Constitution limits the number of times a person can be elected to the office of President of the United States to two terms, and sets additional eligibility conditions for presi ...

, ratified in 1951, no person who has been elected to two presidential terms may be elected to a third. In addition, nine vice presidents have become president by virtue of a

president's intra-term death or

resignation

Resignation is the formal act of relinquishing or vacating one's office or position. A resignation can occur when a person holding a position gained by election or appointment steps down, but leaving a position upon the expiration of a term, or ...

. In all,

45 individuals have served 47 presidencies spanning 60 four-year terms.

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

is the 47th and current president since January 20, 2025.

History and development

Origins

In July 1776, the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

, represented at the

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) was the meetings of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War, which established American independence ...

in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, unanimously adopted the

United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America in the original printing, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the Second Continen ...

in which the colonies declared themselves to be independent

sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

s and no longer under

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

rule.

The affirmation was made in the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

, which was written predominantly by

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and adopted unanimously on July 4, 1776, by the Second Continental Congress. Recognizing the necessity of closely coordinating their efforts against the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

,

the Continental Congress simultaneously began the process of drafting a constitution that would bind the

states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

together. There were long debates on a number of issues, including representation and voting, and the exact powers to be given the central government. Congress finished work on the

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation, officially the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was an agreement and early body of law in the Thirteen Colonies, which served as the nation's first Constitution, frame of government during the Ameri ...

to establish a

perpetual union between the states in November 1777 and sent it to the states for

ratification

Ratification is a principal's legal confirmation of an act of its agent. In international law, ratification is the process by which a state declares its consent to be bound to a treaty. In the case of bilateral treaties, ratification is usuall ...

.

Under the Articles, which

took effect on March 1, 1781, the

Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States from March 1, 1781, until March 3, 1789, during the Confederation ...

was a central political authority without any legislative power. It could make its own resolutions, determinations, and regulations, but not any laws, and could not impose any taxes or enforce local commercial regulations upon its citizens.

This institutional design reflected how Americans believed the deposed British system of

Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, parti ...

and

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

ought to have functioned with respect to the royal

dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

: a superintending body for matters that concerned the entire empire.

The states were out from under any monarchy and assigned some formerly

royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, Privilege (law), privilege, and immunity recognised in common law (and sometimes in Civil law (legal system), civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy) as belonging to the monarch, so ...

s (e.g., making war, receiving ambassadors, etc.) to Congress; the remaining prerogatives were lodged within their own respective state governments. The members of Congress elected a

president of the United States in Congress Assembled to preside over its deliberation as a neutral

discussion moderator

A discussion moderator or debate moderator is a person whose role is to act as a neutral participant in a debate or discussion, holds participants to time limits and tries to keep them from straying off the topic of the questions being raised in ...

. Unrelated to and quite dissimilar from the later office of president of the United States, it was a largely ceremonial position with no executive powers other than presiding over a parliamentary body.

In 1783, the

Treaty of Paris secured independence for each of the former colonies. With peace at hand, the states each turned toward their own internal affairs.

By 1786, Americans found their continental borders besieged and weak and their respective economies in crises as neighboring states agitated trade rivalries with one another. They witnessed their

hard currency

In macroeconomics, hard currency, safe-haven currency, or strong currency is any globally traded currency that serves as a reliable and stable store of value. Factors contributing to a currency's ''hard'' status might include the stability and ...

pouring into foreign markets to pay for imports, their

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

commerce preyed upon by

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

n

pirates

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

, and their foreign-financed Revolutionary War debts unpaid and accruing interest.

Civil and political unrest loomed. Events such as the

Newburgh Conspiracy

The Newburgh Conspiracy was a failed apparent threat by leaders of the Continental Army in March 1783, at the end of the American Revolutionary War. The Army's commander, George Washington, successfully calmed the soldiers and helped secure back ...

and

Shays' Rebellion

Shays's Rebellion was an armed uprising in Western Massachusetts and Worcester, Massachusetts, Worcester in response to a debt crisis among the citizenry and in opposition to the state government's increased efforts to collect taxes on both in ...

demonstrated that the Articles of Confederation were not working, in particular that a stronger national government with an empowered executive was necessary.

Following the successful resolution of commercial and fishing disputes between

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and Maryland at the

Mount Vernon Conference

The Mount Vernon Conference was a meeting of delegates from Virginia and Maryland held at Mount Vernon on March 21–28, 1785, to discuss navigational rights in the states' common waterways. On March 28, 1785, the group drew up a thirteen-point pr ...

in 1785, Virginia called for a trade conference between all the states, set for September 1786 in

Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, with an aim toward resolving further-reaching interstate commercial antagonisms. When the

convention failed for lack of attendance due to suspicions among most of the other states,

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

of New York led the Annapolis delegates in a call for a convention to offer revisions to the Articles, to be held the next spring in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

. Prospects for the next convention appeared bleak until

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

and

Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the seventh Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to cre ...

succeeded in securing

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

's attendance to Philadelphia as a delegate for Virginia.

When the

Constitutional Convention convened in May 1787, the 12 state delegations in attendance (

Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

did not send delegates) brought with them an accumulated experience over a diverse set of institutional arrangements between legislative and executive branches from within their respective state governments. Most states maintained a weak executive without veto or appointment powers, elected annually by the legislature to a single term only, sharing power with an executive council, and countered by a strong legislature.

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

offered the greatest exception, having a strong, unitary governor with veto and appointment power elected to a three-year term, and eligible for reelection to an indefinite number of terms thereafter.

It was through the closed-door negotiations at Philadelphia that the presidency framed in the

U.S. Constitution emerged.

1789–1933

As the nation's first president,

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

established many norms that would come to define the office. His decision to retire after two terms helped address fears that the nation would devolve into monarchy and established a precedent that would not be broken until 1940 and would eventually be made permanent by the

Twenty-Second Amendment

The Twenty-second Amendment (Amendment XXII) to the United States Constitution limits the number of times a person can be elected to the office of President of the United States to two terms, and sets additional eligibility conditions for presi ...

. By the end of his presidency, political parties had developed, with

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

defeating

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

in 1796, the first truly contested presidential election. After Jefferson defeated Adams in 1800, he and his fellow Virginians

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

and

James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

would each serve two terms, eventually dominating the nation's politics during the

Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fe ...

until Adams' son

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

won election in 1824 after the

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

split.

The election of

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

in 1828 was a significant milestone, as Jackson was not part of the Virginia and Massachusetts elite that had held the presidency for its first 40 years.

Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy, also known as Jacksonianism, was a 19th-century political ideology in the United States that restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, i ...

sought to strengthen the presidency at the expense of Congress, while broadening public participation as the nation rapidly expanded westward. However, his successor,

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

, became unpopular after the

Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

, and the death of

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

and subsequent poor relations between

John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

and Congress led to further weakening of the office. Including Van Buren, in the 24 years between 1837 and 1861, six presidential terms would be filled by eight different men, with none serving two terms. The Senate played an important role during this period, with the

Great Triumvirate

In U.S. politics, the Great Triumvirate (known also as the Immortal Trio) was a triumvirate of three statesmen who dominated American politics for much of the first half of the 19th century, namely Henry Clay of Kentucky, Daniel Webster of M ...

of

Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

,

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

, and

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Born in South Carolina, he adamantly defended American s ...

playing key roles in shaping national policy in the 1830s and 1840s until debates over slavery began pulling the nation apart in the 1850s.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

's leadership during the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

has led historians to regard him as one of the nation's greatest presidents. The circumstances of the war and Republican domination of Congress made the office very powerful, and Lincoln's re-election in 1864 was the first time a president had been re-elected since Jackson in 1832. After Lincoln's assassination, his successor

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

lost all political support and was nearly removed from office, with Congress remaining powerful during the two-term presidency of Civil War general

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

. After the end of

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

,

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

would eventually become the first Democratic president elected since before the war, running in three consecutive elections (1884, 1888, 1892) and winning twice. In 1900,

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

became the first incumbent to win re-election since Grant in 1872.

After McKinley's

assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

by

Leon Czolgosz

Leon Frank Czolgosz ( ; ; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American wireworker and Anarchism, anarchist who assassination of William McKinley, assassinated President of the United States, United States president William McKinley on Septe ...

in 1901,

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

became a dominant figure in American politics. Historians believe Roosevelt permanently changed the political system by strengthening the presidency, with some key accomplishments including breaking up trusts, conservationism, labor reforms, making personal character as important as the issues, and hand-picking his successor,

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

. The following decade,

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

led the nation to victory during

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, although Wilson's proposal for the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

was rejected by the Senate.

Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents w ...

, while popular in office, would see his legacy tarnished by scandals, especially

Teapot Dome

The Teapot Dome scandal was a political corruption scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Warren G. Harding. It centered on Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall, who had leased United States Navy, Navy petroleum re ...

, and

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

quickly became very unpopular after failing to alleviate the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

Imperial presidency

The ascendancy of

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

in 1933 led further toward what historians now describe as the

Imperial presidency. Backed by enormous Democratic majorities in Congress and public support for major change, Roosevelt's

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

dramatically increased the size and scope of the federal government, including more executive agencies.

The traditionally small presidential staff was greatly expanded, with the

Executive Office of the President

The Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. The office consists o ...

being created in 1939, none of whom require Senate confirmation.

Roosevelt's unprecedented re-election to a third and fourth term, the victory of the United States in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, and the nation's growing economy all helped established the office as a position of global leadership.

His successors,

Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

and

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, each served two terms as the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

led the presidency to be viewed as the "

leader of the free world

The "Free World" is a propaganda term, primarily used during the Cold War from 1945 to 1991, to refer to the Western Bloc and aligned countries. It was originally coined in the 1930s and used in the Second World War.

The term refers more broa ...

", while

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

was a youthful and popular leader who benefited from the rise of television in the 1960s.

After

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

lost popular support due to the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's presidency collapsed in the

Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

, Congress enacted a series of reforms intended to reassert itself. These included the

War Powers Resolution

The War Powers Resolution (also known as the War Powers Resolution of 1973 or the War Powers Act) () is a federal law intended to check the U.S. president's power to commit the United States to ...

, enacted over Nixon's veto in 1973, and the

Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974

The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (ICA) is a United States federal law that governs the role of the Congress in the United States budget process.

Titles I through IX of the law are also known as the Congressional Budg ...

that sought to strengthen congressional fiscal powers. By 1976,

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

conceded that "the historic pendulum" had swung toward Congress, raising the possibility of a "disruptive" erosion of his ability to govern. Ford failed to win election to a full term and his successor,

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

, failed to win re-election.

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, who had been an actor before beginning his political career, used his talent as a communicator to help reshape the American agenda away from New Deal policies toward more conservative ideology.

After the Cold War, the United States became the world's undisputed leading power.

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

,

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

, and

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

each served two terms as president. Meanwhile, the nation gradually became more politically polarized, leading to the ascendency of increasingly polarized Congressmembers, especially following the

1994 mid-term elections which saw Republicans control the House for the first time in 40 years, and the rise of routine

filibusters in the Senate. Recent presidents have thus increasingly focused on

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

s, agency regulations, and judicial appointments to implement major policies, at the expense of legislation and congressional power. Presidential elections in the 21st century have reflected this continuing polarization, with no candidate except Obama in 2008 winning by more than five percent of the popular vote and two, George W. Bush (

2000

2000 was designated as the International Year for the Culture of Peace and the World Mathematics, Mathematical Year.

Popular culture holds the year 2000 as the first year of the 21st century and the 3rd millennium, because of a tende ...

) and

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

(

2016

2016 was designated as:

* International Year of Pulses by the sixty-eighth session of the United Nations General Assembly.

* International Year of Global Understanding (IYGU) by the International Council for Science (ICSU), the Internationa ...

), winning in the Electoral College while losing the popular vote. Bush (

2004

2004 was designated as an International Year of Rice by the United Nations, and the International Year to Commemorate the Struggle Against Slavery and Its Abolition (by UNESCO).

Events January

* January 3 – Flash Airlines Flight 60 ...

) and Trump (

2024

The year saw the list of ongoing armed conflicts, continuation of major armed conflicts, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Myanmar civil war (2021–present), Myanmar civil war, the Sudanese civil war (2023–present), Sudane ...

) were later re-elected, winning both in the Electoral College and the popular vote.

Critics of presidency's evolution

The nation's

Founding Fathers

The Founding Fathers of the United States, often simply referred to as the Founding Fathers or the Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the War of Independence ...

expected the

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, which was the first branch of government described in the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, to be the dominant branch of government; they did not expect a strong executive department.

However, presidential power has shifted over time, which has resulted in claims that the modern presidency has become too powerful,

unchecked, unbalanced,

and "monarchist" in nature.

In 2008 professor

Dana D. Nelson

Dana D. Nelson is a professor of English at Vanderbilt University and a prominent progressive advocate for citizenship and democracy. She is notable for her criticism—in her books such as '' Bad for Democracy—''of excessive presidential po ...

expressed belief that presidents over the previous thirty years worked towards "undivided presidential control of the executive branch and its agencies".

She criticized proponents of the

unitary executive theory

In American law, the unitary executive theory is a constitutional law theory according to which the president of the United States has sole authority over the executive branch. The theory often comes up in jurisprudential disagreements about t ...

for expanding "the many existing uncheckable executive powers—such as executive orders, decrees, memorandums, proclamations, national security directives and legislative signing statements—that already allow presidents to enact a good deal of foreign and domestic policy without aid, interference or consent from Congress".

, board member of

Americans for Limited Government

Americans for Limited Government (ALG) is a conservative 501(c)(4) non-profit organization "dedicated to restoring the constitutional, limited powers of government at the federal, state, and local level... by fighting to reduce the size and sco ...

, opined that the expanded presidency was "the greatest threat ever to individual freedom and democratic rule".

Legislative powers

Article I, Section1 of the Constitution vests all

lawmaking power in Congress's hands, and

Article 1, Section 6, Clause2 prevents the president (and all other executive branch officers) from simultaneously being a member of Congress. Nevertheless, the modern presidency exerts significant power over legislation, both due to constitutional provisions and historical developments over time.

Signing and vetoing bills

The president's most significant legislative power derives from the

Presentment Clause

The Presentment Clause (Article I, Section 7, Clauses 2 and 3) of the United States Constitution outlines federal legislative procedure by which bills originating in Congress become federal law in the United States.

Text

The Presentment Clau ...

, which gives the president the power to veto any

bill passed by

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

. While Congress can override a presidential veto, it requires a

two-thirds vote

A supermajority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority rules in a democracy can help to prevent a majority from eroding fun ...

of both houses, which is usually very difficult to achieve except for widely supported bipartisan legislation. The framers of the Constitution feared that Congress would seek to increase its power and enable a "tyranny of the majority", so giving the indirectly elected president a veto was viewed as an important check on the legislative power. While George Washington believed the veto should only be used in cases where a bill was unconstitutional, it is now routinely used in cases where presidents have policy disagreements with a bill. The veto – or threat of a veto – has thus evolved to make the modern presidency a central part of the American legislative process.

Specifically, under the Presentment Clause, once a bill has been presented by Congress, the president has three options:

# Sign the legislation within ten days, excluding Sundays, the bill

becomes law.

#

Veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

the legislation within the above timeframe and return it to the house of Congress from which it originated, expressing any objections, the bill does not become law, unless both houses of Congress vote to override the veto by a

two-thirds vote

A supermajority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority rules in a democracy can help to prevent a majority from eroding fun ...

.

# Take no action on the legislation within the above timeframe—the bill becomes law, as if the president had signed it, unless Congress is adjourned at the time, in which case it does not become law, which is known as a

pocket veto

A pocket veto is a legislative maneuver that allows a president or other official with veto power to exercise that power over a bill by taking no action ("keeping it in their pocket"), thus effectively killing the bill without affirmatively vetoin ...

.

In 1996, Congress attempted to enhance the president's veto power with the

Line Item Veto Act. The legislation empowered the president to sign any spending bill into law while simultaneously striking certain spending items within the bill, particularly any new spending, any amount of discretionary spending, or any new limited tax benefit. Congress could then repass that particular item. If the president then vetoed the new legislation, Congress could override the veto by its ordinary means, a two-thirds vote in both houses. In ''

Clinton v. City of New York

''Clinton v. City of New York'', 524 U.S. 417 (1998), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 6–3, that the line-item veto, as implemented in the Line Item Veto Act of 1996, violated the Pr ...

'', , the

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

ruled such a legislative alteration of the veto power to be unconstitutional.

Setting the agenda

For most of American history, candidates for president have sought election on the basis of a promised legislative agenda.

Article II, Section 3, Clause 2 requires the president to recommend such measures to Congress which the president deems "necessary and expedient". This is done through the constitutionally-based

State of the Union

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a Joint session of the United States Congress, joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning ...

address, which usually outlines the president's legislative proposals for the coming year, and through other formal and informal communications with Congress.

The president can be involved in crafting legislation by suggesting, requesting, or even insisting that Congress enact laws that the president believes are needed. Additionally, the president can attempt to shape legislation during the legislative process by exerting influence on individual members of Congress. Presidents possess this power because the Constitution is silent about who can write legislation, but the power is limited because only members of Congress can introduce legislation.

The president or other officials of the executive branch may draft legislation and then ask senators or representatives to introduce these drafts into Congress. Additionally, the president may attempt to have Congress alter proposed legislation by threatening to veto that legislation unless requested changes are made.

Promulgating regulations

Many laws enacted by Congress do not address every possible detail, and either explicitly or implicitly delegate powers of implementation to an appropriate federal agency. As the head of the executive branch, presidents control a vast array of

agencies that can issue regulations with little oversight from Congress.

In the 20th century, critics charged that too many legislative and budgetary powers that should have belonged to Congress had slid into the hands of presidents. One critic charged that presidents could appoint a "virtual army of 'czars'—each wholly unaccountable to Congress yet tasked with spearheading major policy efforts for the White House".

Presidents have been criticized for making

signing statement

A signing statement is a written pronouncement issued by the President of the United States upon the signing of a bill into law. They are usually printed in the Federal Register's '' Compilation of Presidential Documents'' and the '' United State ...

s when signing congressional legislation about how they understand a bill or plan to execute it.

This practice has been criticized by the

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary association, voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students in the United States; national in scope, it is not specific to any single jurisdiction. Founded in 1878, the ABA's stated acti ...

as unconstitutional.

Conservative commentator

George Will

George Frederick Will (born May 4, 1941) is an American libertarian conservative writer and political commentator. He writes columns for ''The Washington Post'' on a regular basis and provides commentary for '' NewsNation''. In 1986, ''The Wall ...

wrote of an "increasingly swollen executive branch" and "the eclipse of Congress".

Convening and adjourning Congress

To allow the government to act quickly in case of a major domestic or international crisis arising when Congress is not in session, the president is empowered by

Article II, Section3 of the Constitution to call a

special session

In a legislature, a special session (also extraordinary session) is a period when the body convenes outside of the normal legislative session. This most frequently occurs in order to complete unfinished tasks for the year (often delayed by confli ...

of one or both houses of Congress. Since

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

first did so in 1797, the president has called the full Congress to convene for a special session on 27 occasions.

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

was the most recent to do so in July 1948, known as the

Turnip Day Session

The Turnip Day Session (or "Turnip Day" session) was a special session of the 80th Congress that began on July 26, 1948 and ended on August 3. President Harry Truman called Congress to convene on that date during his acceptance speech two weeks e ...

. In addition, prior to ratification of the

Twentieth Amendment in 1933, which brought forward the date on which Congress convenes from December to January, newly

inaugurated presidents would routinely call the Senate to meet to confirm nominations or ratify treaties. In practice, the power has fallen into disuse in the modern era as Congress now formally remains in session year-round, convening pro forma sessions every three days even when ostensibly in recess. Correspondingly, the president is authorized to adjourn Congress if the House and Senate cannot agree on the time of adjournment; no president has ever had to exercise this power.

Executive powers

The president is head of the executive branch of the federal government and is

constitutionally obligated to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed". The executive branch has over four million employees, including the military.

Administrative powers

Presidents make

political appointments. An incoming president may make up to 4,000 upon taking office, 1,200 of which must be

confirmed by the U.S. Senate.

Ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or so ...

s, members of the

Cabinet, and various

officers, are among the positions filled by presidential appointment with Senate confirmation.

The power of a president to fire executive officials has long been a contentious political issue. Generally, a president may remove executive officials at will. However, Congress can curtail and constrain a president's authority to fire commissioners of independent regulatory agencies and certain inferior executive officers by

statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

.

To manage the growing federal bureaucracy, presidents have gradually surrounded themselves with many layers of staff, who were eventually organized into the

Executive Office of the President of the United States

The Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. The office consists o ...

. Within the Executive Office, the president's innermost layer of aides, and their assistants, are located in the

White House Office

The White House Office is an entity within the Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP). The White House Office is headed by the White House chief of staff, who is also the head of the Executive Office of the President. The st ...

.

The president also possesses the power to manage operations of the federal government by issuing various

types of directives, such as

presidential proclamation

In the United States, a presidential proclamation is a statement issued by the president of the United States on an issue of public policy. It is a type of presidential directive.

Details

A presidential proclamation is an instrument that:

*s ...

and

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

s. When the president is lawfully exercising one of the constitutionally conferred presidential responsibilities, the scope of this power is broad. Even so, these directives are subject to

judicial review

Judicial review is a process under which a government's executive, legislative, or administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. In a judicial review, a court may invalidate laws, acts, or governmental actions that are in ...

by U.S. federal courts, which can find them to be unconstitutional. Congress can overturn an executive order through legislation.

Foreign affairs

Article II, Section 3, Clause 4

Article II, Section 3, Clause 4 requires the president to "receive Ambassadors". This clause, known as the Reception Clause, has been interpreted to imply that the president possesses broad power over matters of foreign policy, and to provide support for the president's exclusive authority to grant

recognition to a foreign government. The Constitution also empowers the president to appoint United States ambassadors, and to propose and chiefly negotiate agreements between the United States and other countries. Such agreements, upon receiving the advice and consent of the U.S. Senate (by a

two-thirds majority

A supermajority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority rules in a democracy can help to prevent a majority from eroding fund ...

vote), become binding with the force of federal law.

While foreign affairs has always been a significant element of presidential responsibilities, advances in technology since the Constitution's adoption have increased presidential power. Where formerly ambassadors were vested with significant power to independently negotiate on behalf of the United States, presidents now routinely meet directly with leaders of foreign countries.

Commander-in-chief

One of the most important of executive powers is the president's role as

commander-in-chief of the

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

. The power to declare war is constitutionally vested in Congress, but the president has ultimate responsibility for the direction and disposition of the military. The exact degree of authority that the Constitution grants to the president as commander-in-chief has been the subject of much debate throughout history, with Congress at various times granting the president wide authority and at others attempting to restrict that authority. The framers of the Constitution took care to limit the president's powers regarding the military;

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

explained this in

Federalist No. 69:

In the modern era, pursuant to the

War Powers Resolution

The War Powers Resolution (also known as the War Powers Resolution of 1973 or the War Powers Act) () is a federal law intended to check the U.S. president's power to commit the United States to ...

, Congress must authorize any troop deployments longer than 60 days, although that process relies on triggering mechanisms that have never been employed, rendering it ineffectual.

Additionally, Congress provides a check to presidential military power through its control over military spending and regulation. Presidents have historically initiated the process for going to war,

but critics have charged that there have been several conflicts in which presidents did not get official declarations, including

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

's military move into

Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

in 1903,

the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

,

the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

,

and the invasions of

Grenada

Grenada is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The southernmost of the Windward Islands, Grenada is directly south of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and about north of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and the So ...

in 1983

and

Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

in 1989.

The amount of military detail handled personally by the president in wartime has varied greatly. George Washington, the first U.S. president, firmly established

military subordination under civilian authority. In 1794, Washington used his constitutional powers to assemble 12,000 militia to quell the

Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax impo ...

, a conflict in

Western Pennsylvania

Western Pennsylvania is a region in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the Unite ...

involving armed farmers and distillers who refused to pay an excise tax on spirits. According to historian

Joseph Ellis

Joseph John-Michael Ellis III (born July 18, 1943) is an American historian whose work focuses on the lives and times of the Founding Fathers of the United States. His book '' American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson'' won a Nation ...

, this was the "first and only time a sitting American president led troops in the field", though

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

briefly took control of artillery units in

defense of Washington, D.C., during the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

was deeply involved in overall strategy and in day-to-day operations during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, 1861–1865; historians have given Lincoln high praise for his strategic sense and his ability to select and encourage commanders such as

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

.

The present-day operational command of the Armed Forces is delegated to the

Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD, or DOD) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government charged with coordinating and supervising the six U.S. armed services: the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Space Force, ...

and is normally exercised through the

secretary of defense. The

chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) is the presiding officer of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The chairman is the highest-ranking and most senior military officer in the United States Armed Forces Chairman: appointment; gra ...

and the

Combatant Commands assist with the operation as outlined in the presidentially approved Unified Command Plan (UCP).

Judicial powers

The president has the power to nominate

federal judges, including members of the

United States courts of appeals and the

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

. However, these nominations require

Senate confirmation

Advice and consent is an English phrase frequently used in enacting formulae of bills and in other legal or constitutional contexts. It describes either of two situations: where a weak executive branch of a government enacts something previ ...

before they may take office. Securing Senate approval can provide a major obstacle for presidents who wish to orient the federal judiciary toward a particular ideological stance. When nominating judges to

U.S. district courts

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district. Each district covers one U.S. state or a portion of a state. There is at least one fede ...

, presidents often respect the long-standing tradition of

senatorial courtesy

Senatorial courtesy is a long-standing, unwritten, unofficial, and nonbinding constitutional convention in the U.S. describing the tendency of U.S. senators to support a Senate colleague opposing the appointment to federal office of a nominee f ...

. Presidents may also grant

pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

s and

reprieves.

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

pardoned

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

a month after taking office. Presidents often grant pardons shortly before leaving office, like when

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

pardoned

Patty Hearst

Patricia Campbell Hearst (born February 20, 1954) is an American actress and member of the Hearst family. She is the granddaughter of American publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst.

She first became known for the events following her 197 ...

on his last day in office; this is often

controversial

Controversy (, ) is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin '' controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opp ...

.

Two doctrines concerning executive power have developed that enable the president to exercise executive power with a degree of autonomy. The first is

executive privilege

Executive privilege is the right of the president of the United States and other members of the executive branch to maintain confidential communications under certain circumstances within the executive branch and to resist some subpoenas and ot ...

, which allows the president to withhold from disclosure any communications made directly to the president in the performance of executive duties. George Washington first claimed the privilege when Congress requested to see

Chief Justice John Jay

John Jay (, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, diplomat, signatory of the Treaty of Paris (1783), Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served from 1789 to 1795 as the first chief justice of the United ...

's notes from an unpopular treaty negotiation with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

. While not enshrined in the Constitution or any other law, Washington's action created the precedent for the privilege. When Nixon tried to use executive privilege as a reason for not turning over subpoenaed evidence to Congress during the

Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

, the Supreme Court ruled in ''

United States v. Nixon'', that executive privilege did not apply in cases where a president was attempting to avoid criminal prosecution. When Bill Clinton attempted to use executive privilege regarding the

Lewinsky scandal, the Supreme Court ruled in ''

Clinton v. Jones

''Clinton v. Jones'', 520 U.S. 681 (1997), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case establishing that a sitting President of the United States has no immunity from civil law litigation, in federal court, for acts done before taking offi ...

'', that the privilege also could not be used in civil suits. These cases established the

legal precedent

Precedent is a judicial decision that serves as an authority for courts when deciding subsequent identical or similar cases. Fundamental to common law legal systems, precedent operates under the principle of ''stare decisis'' ("to stand by thin ...

that executive privilege is valid, although the exact extent of the privilege has yet to be clearly defined. Additionally, federal courts have allowed this privilege to radiate outward and protect other executive branch employees but have weakened that protection for those executive branch communications that do not involve the president.

The

state secrets privilege allows the president and the executive branch to withhold information or documents from

discovery

Discovery may refer to:

* Discovery (observation), observing or finding something unknown

* Discovery (fiction), a character's learning something unknown

* Discovery (law), a process in courts of law relating to evidence

Discovery, The Discovery ...

in legal proceedings if such release would harm

national security

National security, or national defence (national defense in American English), is the security and Defence (military), defence of a sovereign state, including its Citizenship, citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of ...

. Precedent for the privilege arose early in the 19th century when

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...