Ottoman Empire–United Kingdom Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

British foreign policy in the Middle East has involved multiple considerations, particularly over the last two and a half centuries. These included maintaining access to

Europe was generally peaceful; the Greek's long war of independence was the major military conflict in the 1820s. Serbia had gained its autonomy from Ottoman Empire in 1815. The Greek rebellion came next starting in 1821, with a rebellion indirectly sponsored by Russia. The Greeks had strong intellectual and business communities which employed propaganda echoing the French Revolution that appealed to the romanticism of Western Europe. Despite harsh Ottoman reprisals they kept their rebellion alive. Sympathizers like British poet

Europe was generally peaceful; the Greek's long war of independence was the major military conflict in the 1820s. Serbia had gained its autonomy from Ottoman Empire in 1815. The Greek rebellion came next starting in 1821, with a rebellion indirectly sponsored by Russia. The Greeks had strong intellectual and business communities which employed propaganda echoing the French Revolution that appealed to the romanticism of Western Europe. Despite harsh Ottoman reprisals they kept their rebellion alive. Sympathizers like British poet

In 1650, British diplomats signed a treaty with the Sultan at

In 1650, British diplomats signed a treaty with the Sultan at

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer

online

the major scholarly study. * Barr, James. "A Line in the Sand: British-French Rivalry in the Middle East 1915–1948." ''Asian Affairs'' 43.2 (2012): 237–252. * Brenchley, Frank. ''Britain and the Middle East: Economic History, 1945-87'' (1991). * Bullard, Reader. ''Britain and the Middle East from Earliest Times to 1963'' (3rd ed. 1963) * Cleveland, William L., and Martin Bunton. ''A History Of The Modern Middle East'' (6th ed. 201

4th ed. online

* Corbett, Julian Stafford. ''England in the Mediterranean; a study of the rise and influence of British power within the Straits, 1603-1713'' (1904

online

* D'Angelo, Michela. "In the 'English' Mediterranean (1511–1815)." ''Journal of Mediterranean Studies'' 12.2 (2002): 271–285. * Deringil, Selim. "The Ottoman Response to the Egyptian Crisis of 1881-82" ''Middle Eastern Studies'' (1988) 24#1 pp. 3-2

online

* Dietz, Peter. ''The British in the Mediterranean'' (Potomac Books Inc, 1994). * Fieldhouse, D. K. ''Western Imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958'' (Oxford UP, 2006) * Harrison, Robert. ''Britain in the Middle East: 1619-1971'' (2016) short scholarly narrativ

excerpt

* Hattendorf, John B., ed. ''Naval Strategy and Power in the Mediterranean: Past, Present and Future'' (Routledge, 2013). * Holland, Robert. "Cyprus and Malta: two colonial experiences." ''Journal of Mediterranean Studies'' 23.1 (2014): 9–20. * Holland, Robert. ''Blue-water empire: the British in the Mediterranean since 1800'' (Penguin UK, 2012)

excerpt

* Laqueur, Walter. ''The Struggle for the Middle East: The Soviet Union and the Middle East 1958-70'' (1972

online

* Louis, William Roger. ''The British Empire in the Middle East, 1945–1951: Arab Nationalism, the United States, and Postwar Imperialism'' (1984) * MacArthur-Seal, Daniel-Joseph. "Turkey and Britain: from enemies to allies, 1914–1939." ''Middle Eastern Studies'' (2018): 737-743. * Mahajan, Sneh. ''British Foreign Policy 1874-1914: The Role of India'' (2002). * Anderson, M.S. ''The Eastern Question, 1774-1923: A Study in International Relations'' (1966

the major scholarly study. * Marriott, J. A. R. ''The Eastern Question An Historical Study In European Diplomacy'' (1940), Older comprehensive study; more up-to-date is Anderson (1966

Online

* Millman, Richard. ''Britain and the Eastern Question, 1875–1878'' (1979) * Monroe, Elizabeth. ''Britain's moment in the Middle East, 1914-1956'' (1964

online

* Olson, James E. and Robert Shadle, eds., ''Historical dictionary of the British Empire'' (1996) * Owen, Roger. ''Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul'' (Oxford UP, 2005

Online review

On Egypt 1882-1907. * Pack, S.W.C ''Sea Power in the Mediterranean'' – has a complete list of fleet commanders * Panton, Kenneth J. ''Historical Dictionary of the British Empire'' (2015). * Schumacher, Leslie Rogne. "A 'Lasting Solution': the Eastern Question and British Imperialism, 1875-1878." (2012)

online; Detailed bibliography

* Seton-Watson, R. W. ''Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern question; a study in diplomacy and party politics'' (1972

Online

* Seton-Watson, R. W. ''Britain in Europe 1789-1914, a Survey of Foreign Policy'' (1937

Online

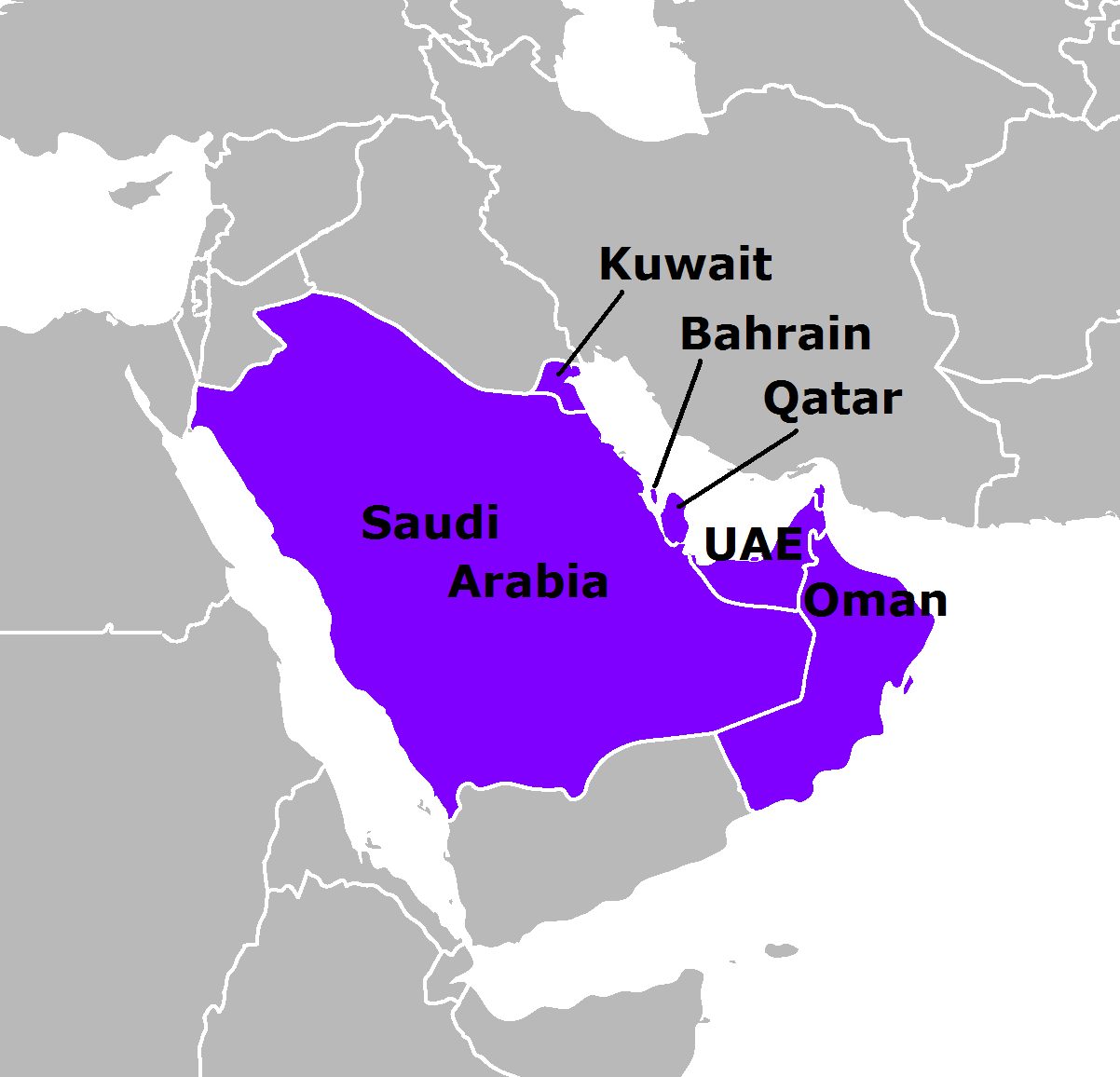

* Smith, Simon C. ''Ending Empire in the Middle East: Britain, the United States and Post-war Decolonization, 1945-1973'' (2012). * Smith, Simon C. ''Britain's Revival and Fall in the Gulf: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the Trucial States, 1950-71'' (2004) * Smith, Simon C. ''Britain and the Arab Gulf after Empire: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, 1971-1981'' (Routledge, 2019). * Steele, David. "Three British Prime Ministers and the Survival of the Ottoman Empire, 1855–1902." ''Middle Eastern Studies'' 50.1 (2014): 43-60, On Palmerston, Gladstone and Salisbury. * Syrett, David. "A Study of Peacetime Operations: The Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, 1752–5." ''The Mariner's Mirror'' 90.1 (2004): 42-50. * Talbot, Michael. ''British-Ottoman Relations, 1661-1807: Commerce and Diplomatic Practice in Eighteenth-Century Istanbul'' (Boydell & Brewer, 2017). * Thomas, Martin, and Richard Toye. "Arguing about intervention: a comparison of British and French rhetoric surrounding the 1882 and 1956 invasions of Egypt." ''Historical Journal'' 58.4 (2015): 1081-111

online

* Tuchman, Barbara W. ''Bible and Sword: England and Palestine from the Bronze Age to Balfour'' (1982), popular history of Britain in the Middle East

online

* Uyar, Mesut, and Edward J. Erickson. ''A Military History of the Ottomans: From Osman to Atatürk'' (ABC-CLIO, 2009). * Venn, Fiona. "The wartime ‘special relationship’? From oil war to Anglo-American Oil Agreement, 1939–1945." ''Journal of Transatlantic Studies'' 10.2 (2012): 119-133. * Williams, Kenneth. '' Britain And The Mediterranean'' (1940

online free

* Yenen, Alp. "Elusive forces in illusive eyes: British officialdom's perception of the Anatolian resistance movement." ''Middle Eastern Studies'' 54.5 (2018): 788-810

online

* Yergin, Daniel. ''The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power'' (1991)

online free to borrow

* Fraser, T. G. ed. ''The Middle East, 1914-1979'' (1980) 102 primary sources; focus on Palestine/Israel * Hurewitz, J. C. ed. ''The Middle East and North Africa in world politics: A documentary record'' ''vol 1: European expansion: 1535-1914'' (1975); ''vol 2: A Documentary Record 1914-1956'' (195

vol 2 online

The Middle East : peace and the changing order

from the

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

, blocking Russian or French threats to that access, protecting the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

, supporting the declining Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

against Russian threats, guaranteeing an oil supply after 1900 from Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

fields, protecting Egypt and other possessions in the Middle East, and enforcing Britain's naval role in the Mediterranean. The timeframe of major concern stretches from the 1770s when the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

began to dominate the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

, down to the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

of the mid-20th century and involvement in the Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

in the early 21st. These policies are an integral part of the history of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

The history of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom covers English, British, and United Kingdom's foreign policy from about 1500 to 2000. For the current situation since 2000 see foreign relations of the United Kingdom.

Britain from 1750 t ...

.

Napoleon's threat

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, the leader of the French wars against Britain from the late 1790s until 1815, used the French fleet to convey a large invasion army to Egypt, a major remote province of the Ottoman Empire. British commercial interests represented by the Levant Company

The Levant Company was an English chartered company formed in 1592. Elizabeth I of England approved its initial charter on 11 September 1592 when the Venice Company (1583) and the Turkey Company (1581) merged, because their charters had expired, ...

had a successful base in Egypt, and indeed the company handled all Egypt's diplomacy. The British responded and sank the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile

The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay; ) was fought between the Royal Navy and the French Navy at Abu Qir Bay, Aboukir Bay in Ottoman Egypt, Egypt between 1–3 August 1798. It was the climax of the Mediterranean ca ...

in 1798, thereby trapping Napoleon's army. Napoleon escaped. The Army he left behind was defeated by the British and the survivors returned to France in 1801. In 1807 when Britain was at war with the Ottomans, the British sent a force to Alexandria, but it was defeated by the Egyptians under Mohammed Ali and withdrew. Britain absorbed the Levant company into the Foreign Office by 1825.

Greek independence: 1821–1833

Europe was generally peaceful; the Greek's long war of independence was the major military conflict in the 1820s. Serbia had gained its autonomy from Ottoman Empire in 1815. The Greek rebellion came next starting in 1821, with a rebellion indirectly sponsored by Russia. The Greeks had strong intellectual and business communities which employed propaganda echoing the French Revolution that appealed to the romanticism of Western Europe. Despite harsh Ottoman reprisals they kept their rebellion alive. Sympathizers like British poet

Europe was generally peaceful; the Greek's long war of independence was the major military conflict in the 1820s. Serbia had gained its autonomy from Ottoman Empire in 1815. The Greek rebellion came next starting in 1821, with a rebellion indirectly sponsored by Russia. The Greeks had strong intellectual and business communities which employed propaganda echoing the French Revolution that appealed to the romanticism of Western Europe. Despite harsh Ottoman reprisals they kept their rebellion alive. Sympathizers like British poet Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

played a major role in shaping British opinion to strongly favor the Greeks, especially among Philosophical Radicals, the Whigs, and the Evangelicals. However, the top British foreign policy makers George Canning

George Canning (; 11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as foreign secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the U ...

(1770–1827) and Viscount Castlereagh

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status. The status and any domain held by a viscount is a viscounty.

In the case of French viscounts, the title is s ...

(1769–1822) were much more cautious. They agreed that the Ottoman Empire was "barbarous" but they decided it was a necessary evil. British policy down to 1914 was to preserve the Ottoman Empire, especially against hostile pressures from Russia. However, when Ottoman behavior was outrageously oppressive against Christians, London demanded reforms and concessions.

The context of the three Great Powers' intervention was Russia's long-running expansion at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire. However, Russia's ambitions in the region were seen as a major geostrategic threat by the other European powers. Austria feared the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire would destabilize its southern borders. Russia gave strong emotional support for the fellow Orthodox Christian Greeks. The British were motivated by strong public support for the Greeks. The government in London paid special attention to the powerful role of the Royal Navy throughout the entire Mediterranean region. Fearing unilateral Russian action in support of the Greeks, Britain and France bound Russia by treaty to a joint intervention which aimed to secure Greek autonomy whilst preserving Ottoman territorial integrity as a check on Russia.

The Powers agreed, by the Treaty of London (1827)

The Treaty of London (, ) was signed in London on 6 July, 1827 by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Bourbon Restoration France and the Russian Empire. The three main European powers had called upon Greece and the Ottoman Empire to ...

, to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to Greece to enforce their policy. The decisive Allied naval victory at the Battle of Navarino

The Battle of Navarino was a naval battle fought on 20 October (O.S. 8 October) 1827, during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), in Navarino Bay (modern Pylos), on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. Allied ...

broke the military power of the Ottomans and their Egyptian allies. Victory saved the fledgling Greek Republic from collapse. But it required two more military interventions, by Russia in the form of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 and by a French expeditionary force to the Peloponnese to force the withdrawal of Ottoman forces from central and southern Greece and to finally secure Greek independence. Greek nationalists proclaimed a new "Great Idea" whereby the little nation of 800,000 would expand to include all the millions of Greek Orthodox believers in the region now under Ottoman control, with Constantinople to be reclaimed as its capital. This idea was the antithesis of the British goal of maintaining the Ottoman Empire, and London systematically opposed the Greeks until the "Great Idea" finally collapsed in 1922 when Turkey drove the Greeks out of Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

.

Crimean War

TheCrimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

(from 1853 to 1856) was a major conflict fought in the Crimean Peninsula. The Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

lost to an alliance made up of Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire. The immediate causes of the war were minor. The longer-term causes involved the decline of the Ottoman Empire

In the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire faced threats on numerous frontiers from multiple industrialised European powers as well as internal instabilities. Outsider influence, rise of nationalism and internal corruption demanded the Empire to lo ...

and Russia's misunderstanding of the British position. Tsar Nicholas I

Nicholas I, group=pron (Russian language, Russian: Николай I Павлович; – ) was Emperor of Russia, List of rulers of Partitioned Poland#Kings of the Kingdom of Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 18 ...

visited London in person and consulted with Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in fo ...

regarding what would happen if the Ottoman Empire collapsed and had to be split up. The tsar misread Britain’s position as supporting Russian aggression, while London actually sided with Paris against any breakup of the Ottoman Empire and Russian expansion. When Aberdeen became Prime Minister in 1852, the tsar mistakenly believed he had British approval for action against Turkey and was shocked when Britain declared war. Despite Aberdeen's opposition to the war, public opinion demanded it, leading to his resignation. The new prime minister was Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

who strongly opposed Russia. He defined the popular imagination which saw the war against Russia is a commitment to British principles, notably the defense of liberty, civilization, free trade; and championing the underdog. The fighting was largely limited to actions in the Crimean Peninsula and the Black Sea. Both sides badly mishandled operations; the world was aghast at the extremely high death rates due to disease. In the end, the British-French coalition prevailed and Russia lost control of the Black Sea. Russia in 1871 regained control of the Black Sea.

Pompous aristocracy was a loser in the war, the winners were the ideals of middle-class efficiency, progress, and peaceful reconciliation. The war's great hero was Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during th ...

, the nurse who brought scientific management and expertise to heal the horrible sufferings of the tens of thousands of sick and dying British soldiers. according to historian R. B. McCallum the Crimean War:

: remained as a classic example, a perfect demonstration-peace, of how governments may plunge into war, how strong ambassadors may mislead weak prime ministers, how the public may be worked up into a facile fury, and how the achievements of the war may crumble to nothing. The Bright-Cobden criticism of the war was remembered and to a large extent accepted. Isolation from European entanglements seemed more than ever desirable.

Seizure of Egypt, 1882

As owners of the Suez Canal, both British and French governments had strong interests in the stability of Egypt. Most of the traffic was by British merchant ships. However, in 1881 theʻUrabi revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution (), was a nationalist uprising in the Khedivate of Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed Urabi and sought to depose the khedive, Tewfik Pasha, and end Imperial ...

broke out-- it was a nationalist movement led by Ahmed ʻUrabi

Ahmed Urabi (; Arabic: ; 31 March 1841 – 21 September 1911), also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha, was an Egyptian military officer. He was the first political and military leader in Egypt to rise from the ''fellahin'' (peasantry). Urabi p ...

(1841–1911) against the administration of Khedive

Khedive ( ; ; ) was an honorific title of Classical Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the Khedive of Egypt, viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Khedive" ''Encyclopaedi ...

Tewfik, who collaborated closely with the British and French. Combined with the complete turmoil in Egyptian finances, the threat to the Suez Canal, and embarrassment to British prestige if it could not handle a revolt, London found the situation intolerable and decided to end it by force. The French, however, did not join in. On 11 July 1882, Prime Minister William E. Gladstone ordered the bombardment of Alexandria

The Bombardment of Alexandria in Egypt by the British Mediterranean Fleet took place on 11–13 July 1882.

Admiral Beauchamp Seymour was in command of a fleet of fifteen Royal Navy ironclad ships which had previously sailed to the harbor of Al ...

which launched the short decisive Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. Egypt nominally remained under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, and France and other nations had representation, but British officials made the decisions. The Khedive

Khedive ( ; ; ) was an honorific title of Classical Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the Khedive of Egypt, viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Khedive" ''Encyclopaedi ...

(Viceroy) was the Ottoman official in Cairo, appointed by the Sultan in Constantinople. He appointed the Council of ministers and high-ranking military officer; he controlled the treasury and sign treaties. In practice, he operated under the close supervision of the British consul general. The dominant personality was Consul-general Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer, (; 26 February 1841 – 29 January 1917) was a British statesman, diplomat and colonial administrator. He served as the British controller-general in Egypt during 1879, part of the international control whic ...

(1841–1917). He was thoroughly familiar with the British Raj in India, and applied similar policies to take full control of the Egyptian economy. London repeatedly promised to depart in a few years. It did so 66 times until 1914, when it gave up the pretense and assumed permanent control.

Historian A.J.P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was an English historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his telev ...

says that the seizure of Egypt "was a great event; indeed, the only real event in international relations between the Battle of Sedan and the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese war."

Taylor emphasizes long-term impact:

Gladstone and the Liberals had a reputation for strong opposition to imperialism, so historians have long debated the explanation for this reversal of policy. The most influential was a study by John Robinson and Ronald Gallagher, ''Africa and the Victorians'' (1961). They focused on The Imperialism of Free Trade

"The Imperialism of Free Trade" is an academic article by John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson first published in '' The Economic History Review'' in 1953. It argued that the New Imperialism could be best characterised as a continuation of a longer ...

and promoted the highly influential Cambridge School of historiography

The Cambridge School of historiography is a school of thought which approaches the study of the British Empire from the imperialist point of view. It emerged especially at the University of Cambridge in the 1960s. John Andrew Gallagher (1919–80) ...

. They argue that the Liberals had no long-term plan for imperialism but acted out of necessity to protect the Suez Canal amid a nationalist revolt and the threat to law and order in Egypt. Gladstone's decision was influenced by strained relations with France and the actions of British officials in Egypt. Critics like Cain and Hopkins emphasize the need to protect British financial investments in Egypt, downplaying the risks to the Suez Canal. Unlike Marxists, they focus on "gentlemanly" financial interests rather than industrial capitalism.

A.G. Hopkins rejected Robinson and Gallagher's argument, citing original documents to claim that there was no perceived danger to the Suez Canal from the ‘Urabi movement, and that ‘Urabi and his forces were not chaotic "anarchists", but rather maintained law and order. He argues that Gladstone's cabinet was motivated by the need to protect British bondholders' investments in Egypt and to gain domestic political popularity. Hopkins points to the significant growth of British investments in Egypt, driven by the Khedive's debt from the Suez Canal's construction, and the close ties between the British government and the economic sector. He writes that Britain's economic interests occurred simultaneously with a desire within one element of the ruling Liberal Party for a militant foreign policy in order to gain the domestic political popularity that enabled it to compete with the Conservative Party. Hopkins cites a letter from Edward Malet

Sir Edward Baldwin Malet, 4th Baronet (10 October 1837 – 29 June 1908) was a British diplomat.

Edward Malet came from a family of diplomats; his father was Sir Alexander Malet, British minister to Württemberg and later to the German Co ...

, the British consul general in Egypt at the time, to a member of the Gladstone Cabinet offering his congratulations on the invasion: "You have fought the battle of all Christendom and history will acknowledge it. May I also venture to say that it has given the Liberal Party a new lease of popularity and power." However, Dan Halvorson argues that the protection of the Suez Canal and British financial and trade interests were secondary and derivative. Instead, the primary motivation was the vindication of British prestige in both Europe and especially in India by suppressing the threat to "civilised" order posed by the Urabist revolt.

Armenia

The Ottoman Empire leadership had long been hostile to its Armenian element, and in World War I accused it of favouring Russia. The result was an attempt to relocate and ethnically cleanse Armenians, in which hundreds of thousands died in theArmenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

. Since the late 1870s Gladstone had moved Britain into playing a leading role in denouncing the harsh policies and atrocities and mobilizing world opinion. In 1878–1883 Germany followed the lead of Britain in adopting an Eastern policy that demanded reforms in the Ottoman policies that would ameliorate the position of the Armenian minority.

Persian Gulf

Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

declaring that the bond between the two nations should be "unshook to the end of time." British policy was to expand its presence in the Persian Gulf region, with a strong base in Oman. Two London-based companies were used, first the Levant Company and later the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

. The shock of Napoleon's 1798 expedition to Egypt led London to significantly strengthen its ties in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf

The Arab states of the Persian Gulf, also known as the Gulf Arab states (), refers to a group of Arab states bordering the Persian Gulf. There are seven member states of the Arab League in the region: Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Saudi ...

, pushing out the French and Dutch rivals, and upgrading the East India Company operations to diplomatic status. The East India Company also expanded relations with other sultanates in the region, and expanded operations into southern Persia. There was something of a standoff with Russian interests, which were active in northern Persia. The commercial agreements allowed for British control of mineral resources, but the first oil was discovered in the region in Persia in 1908. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC; ) was a British company founded in 1909 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Persia (Iran). The British government purchased 51% of the company in 1914, gaining a controlling numbe ...

activated the concession and quickly became the Royal Navy's main source of fuel for the new diesel engines that were replacing coal-burning steam engines. The company merged into BP (British Petroleum). The main advantage of oil was that a warship could easily carry fuel for long voyages without having to make repeated stops at coaling stations.Aden

When Napoleon threatened Egypt in 1798, one of his threats was to cut off British access to India. In response the East India Company (EIC) negotiated an agreement with Aden’s sultan that provided rights to the deepwater harbor on Arabia's southern coast including a strategically important coaling station. The EIC took full control in 1839. With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Aden took a much greater strategic an economic importance. To protect against threats from the Ottoman Empire, the EIC negotiated agreements with sheikhs in the hinterland, and by 1900 had absorbed their territory. Local demands for independence led in 1937 to designation of Aden as a Crown Colony separate from India. Nearby areas were consolidated as the Western Aden protectorate and Eastern Aden protectorate. Some 1300 sheikhs and chieftains signed agreements and remained in power locally. They resisted demands from leftist labor unions based in the ports and refineries, and strongly opposed the threat of Yemen to incorporate them. London considered the military base and Aiden as essential to protect its oil interest in the Persian Gulf. Expenses mounted, budgets were cut, and London misinterpreted the mounting internal conflicts. In 1963 the Federation of South Arabia was set up that merged the colony and 15 of the protectorates. Independence was announced, leading to theAden Emergency

The Aden Emergency, also known as the 14 October Revolution () or as the Radfan Uprising, was an armed rebellion by the National Liberation Front (South Yemen), National Liberation Front (NLF) and the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South ...

--a civil war involving Soviet-backed National Liberation Front fighting the Egyptian-backed Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen

The Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY; ) was an Arab nationalist military organization operating in the Federation of South Arabia (a British protectorate; now Southern Yemen) in the 1960s. As the British tried to exit, Abd ...

. In 1967 the Labour government under Harold Wilson withdrew its forces from Aden. The National Liberation Front quickly took power and announced the creation of a communist People’s Republic of South Yemen, deposing the traditional leaders in the sheikhdoms and sultanates. It was merged with Yemen into People's Democratic Republic of Yemen

South Yemen, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, abbreviated to Democratic Yemen, was a country in South Arabia that existed in what is now southeast Yemen from 1967 until its unification with the Yemen Arab Republic in 19 ...

, with close ties to Moscow.

World War I era

World War I

The Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of Germany and immediately became an enemy of Britain and France. Four major Allied operations attacked the Ottoman holdings. The Gallipoli Campaign to control the Straits failed in 1915-1916. The firstMesopotamian campaign

The Mesopotamian campaign or Mesopotamian front () was a campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I fought between the British Empire, with troops from United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Britain, Australia and the vast major ...

invading Iraq from India also failed. The second one captured Baghdad in 1917. The Sinai and Palestine campaign

The Sinai and Palestine campaign was part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I, taking place between January 1915 and October 1918. The British Empire, the French Third Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy fought alongside the Arab Revol ...

from Egypt was a British success. By 1918 the Ottoman Empire was a military failure/ It signed an armistice in late October that amounted to surrender.Partition of Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred afterWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the occupation of Istanbul

The occupation of Istanbul () or occupation of Constantinople (12 November 1918 – 4 October 1923), the capital of the Ottoman Empire, by United Kingdom, British, France, French, Italy, Italian, and Greece, Greek forces, took place in accordan ...

by British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

, French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

, and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

troops in November 1918. The partitioning was planned in several agreements made by the Allied Powers early in the course of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, notably the Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from Russia and Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire.

T ...

, after the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

had joined Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

to form the Ottoman–German Alliance. The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

. The Ottoman Empire had been the leading Islamic state

The Islamic State (IS), also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Daesh, is a transnational Salafi jihadism, Salafi jihadist organization and unrecognized quasi-state. IS ...

in geopolitical

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of states: ''de facto'' independen ...

, cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

and ideological

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

terms. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

and the Republic of Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

. Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement (), also known as the Anatolian Movement (), the Nationalist Movement (), and the Kemalists (, ''Kemalciler'' or ''Kemalistler''), included political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resu ...

but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonization after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

The sometimes-violent creation of protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

s in Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

and Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, and the proposed division of Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

along communal lines, is thought to have been a part of the larger strategy of ensuring tension in the Middle East, thus necessitating the role of Western colonial powers (at that time Britain, France and Italy) as peace brokers and arms suppliers. The League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

granted the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (; , also referred to as the Levant States; 1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate founded in the aftermath of the First World War and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, concerning the territori ...

, the British Mandate for Mesopotamia (later Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

) and the British Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordanwhich had been part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuriesfollowing the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in Wo ...

, later divided into Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

and the Emirate of Transjordan

The Emirate of Transjordan (), officially the Amirate of Trans-Jordan, was a British protectorate established on 11 April 1921,Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

became the Kingdom of Hejaz

The Hashemite Kingdom of Hejaz (, ''Al-Mamlakah al-Ḥijāziyyah Al-Hāshimiyyah'') was a state in the Hejaz region of Western Asia that included the western portion of the Arabian Peninsula that was ruled by the Hashemite dynasty. It was self ...

, which the Sultanate of Nejd

The Sultanate of Nejd (, ') was the third iteration of the Third Saudi State, from 1921 to 1926. It was a monarchy led by the House of Saud, and a legal predecessor of modern-day Saudi Arabia. This version of the Third Saudi State was created ...

(today Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

) was allowed to annex, and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

The Kingdom of Yemen (), officially the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen () and also known simply as Yemen or, retrospectively, as North Yemen, was a state that existed between 1918 and 1970 in the northwestern part of the modern country of Yemen ...

. The Empire's possessions on the western shores of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

were variously annexed by Saudi Arabia ( al-Ahsa and Qatif

Qatif Governorate ( ''Al-Qaṭīf'') is a list of governorates of Saudi Arabia, governorate and urban area located in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. It extends from Ras Tanura and Jubail in the north to Damma ...

), or remained British protectorates

British protectorates were protectorates under the jurisdiction of the British government. Many territories which became British protectorates already had local rulers with whom the Crown negotiated through treaty, acknowledging their status wh ...

(Kuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

, Bahrain

Bahrain, officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, is an island country in West Asia. Situated on the Persian Gulf, it comprises a small archipelago of 50 natural islands and an additional 33 artificial islands, centered on Bahrain Island, which mak ...

, and Qatar

Qatar, officially the State of Qatar, is a country in West Asia. It occupies the Geography of Qatar, Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it shares Qatar–Saudi Arabia border, its sole land b ...

) and became the Arab States of the Persian Gulf

The Arab states of the Persian Gulf, also known as the Gulf Arab states (), refers to a group of Arab states bordering the Persian Gulf. There are seven member states of the Arab League in the region: Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Saudi ...

.

Postwar planning

In the 1920s, British policymakers debated two alternative approaches to Middle Eastern issues. Many diplomats adopted the line of thought ofT. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British Army officer, archaeologist, diplomat and writer known for his role during the Arab Revolt and Sinai and Palestine campaign against the Ottoman Empire in the First W ...

favoring Arab national ideals. They backed the Hashemite family for top leadership positions. The other approach led by Arnold Wilson

Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson (18 July 1884 – 31 May 1940) was a British soldier, colonial administrator, Conservative politician, writer and editor. Wilson served under Percy Cox, the colonial administrator of Mesopotamia ( Mandatory Iraq) dur ...

, the civil commissioner for Iraq, reflected the views of the India office. They argue that direct British rule was essential, and the Hashemite family was too supportive of policies that would interfere with British interests. The decision was to support Arab nationalism, sidetracked Wilson, and consolidate power in the Colonial Office.

New British Mandates and colonies

The British were awarded three mandated territories, with one ofSharif Hussein

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Qatadah branch of the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif of Mecca, Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after proclaiming the Great Arab Revolt against ...

's sons, Faisal

Faisal, Faisel, Fayçal or Faysal () is an Arabic given name.

Faisal, Fayçal or Faysal may also refer to:

People

* King Faisal (disambiguation)

** Faisal I of Iraq and Syria (1885–1933), leader during the Arab Revolt

** Faisal II of Iraq (19 ...

, installed as King of Iraq and Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom o ...

providing a throne for another of Hussein's sons, Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

. Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

was placed under direct British administration, and the Jewish population was allowed to increase, initially under British protection. Most of the Arabian peninsula fell to another British ally, Ibn Saud

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud (; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted as 1876, although a few sources give it as 1880. According to British author Robert Lacey's book ''The Kingdom'', ...

, who created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

in 1932.

Mandate for Mesopotamia

Mosul was allocated to France under the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement and was subsequently given to Britain under the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement. Great Britain and Turkey disputed control of the former Ottoman province ofMosul

Mosul ( ; , , ; ; ; ) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. It is the second largest city in Iraq overall after the capital Baghdad. Situated on the banks of Tigris, the city encloses the ruins of the ...

in the 1920s. Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (, ) is a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–1923 and signed in the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially resolved the conflict that had initially ...

Mosul fell under the British Mandate of Mesopotamia

The Mandate for Mesopotamia () was a proposed League of Nations mandate to cover Ottoman Iraq (Mesopotamia). It would have been entrusted to the United Kingdom but was superseded by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, an agreement between Britain and Ira ...

, but the new Turkish republic claimed the province as part of its historic heartland. A three-person League of Nations committee went to the region in 1924 to study the case and in 1925 recommended the region remain connected to Iraq, and that the UK should hold the mandate for another 25 years, to assure the autonomous rights of the Kurd

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

ish population. Turkey rejected this decision. Nonetheless, Britain, Iraq and Turkey made a treaty on 5 June 1926, that mostly followed the decision of the League Council. Mosul stayed under British Mandate of Mesopotamia

The Mandate for Mesopotamia () was a proposed League of Nations mandate to cover Ottoman Iraq (Mesopotamia). It would have been entrusted to the United Kingdom but was superseded by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, an agreement between Britain and Ira ...

until Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

was granted independence in 1932 by the urging of King Faisal, though the British retained military bases and transit rights for their forces in the country.

Mandate for Palestine

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British Army officer, archaeologist, diplomat and writer known for his role during the Arab Revolt and Sinai and Palestine campaign against the Ottoman Empire in the First W ...

(aka Lawrence of Arabia), the establishment of a united Arab state covering a large area of the Arab Middle East in exchange for Arab support of the British during the war. The Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

of 1917 encouraged Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

ish ambitions for a national home. Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite

The Hashemites (), also House of Hashim, are the Dynasty, royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Hejaz, Hejaz (1916–1925), Arab Kingdom of Syria, Syria (1920), and Kingd ...

family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Great Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ), also known as the Great Arab Revolt ( ), was an armed uprising by the Hashemite-led Arabs of the Hejaz against the Ottoman Empire amidst the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

On the basis of the McMahon–Hussein Co ...

.

The Arab Revolt, which was in part orchestrated by Lawrence, resulted in British forces under General Edmund Allenby

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer and imperial governor. He fought in the Second Boer ...

defeating the Ottoman forces in 1917 in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The Sinai and Palestine campaign was part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I, taking place between January 1915 and October 1918. The British Empire, the French Third Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy fought alongside the Arab Revol ...

and occupying Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

and Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

. The land was administered by the British for the remainder of the war.

The United Kingdom was granted control of Palestine by the Versailles Peace Conference

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines Department of Île-de-France region in France.

The palace is owned by the government of F ...

which established the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

in 1919. Herbert Samuel

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel (6 November 1870 – 5 February 1963) was a British Liberal politician who was the party leader from 1931 to 1935.

He was the first nominally-practising Jew to serve as a Cabinet minister and to becom ...

, a former Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters.

History

The practice of having a government official ...

in the British cabinet

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the senior decision-making body of the Government of the United Kingdom. A committee of the Privy Council, it is chaired by the Prime Minister and its members include Secretaries of State and senior Mini ...

who was instrumental in drafting the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

, was appointed the first High Commissioner in Palestine. In 1920 at the San Remo conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Castle Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution ...

, in Italy, the League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

over Palestine was assigned to Britain. In 1923 Britain transferred a part of the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights, or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in t ...

to the French Mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (; , also referred to as the Levant States; 1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate founded in the aftermath of the First World War and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, concerning the territories ...

, in exchange for the Metula

Metula () is a town in the Northern District of Israel. It abuts the Israel-Lebanon border, and had a population of in .

History Bronze and Iron Age

Metula is located near the sites of the biblical cities of Dan, Abel Beth Maacah, and Ijon ...

region.

Iraq

The British seized Baghdad in March 1917. In 1918 it was joined to Mosul and Basra in the new nation ofIraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

using a League of Nations Mandate. Experts from India designed the new system, which favoured direct rule by British appointees, and demonstrated distrust of the aptitude of local Arabs for self-government. The old Ottoman laws were discarded and replaced by new codes for civil and criminal law, based on Indian practice. The Indian rupee became the currency. The army and police were staffed with Indians who had proven their loyalty to the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

.

The large-scale Iraqi revolt of 1920

The Iraqi Revolt of 1920, also known as the Iraqi War of Independence or Great Iraqi Revolution began in Baghdad in the summer of 1920 with mass demonstrations by Iraqis, including protests by embittered officers from the old Ottoman Army, agai ...

was crushed in the summer of 1920 but it was a major stimulus for Arab nationalism. The Turkish Petroleum Company was given a monopoly on exploration and production in 1925. Important oil reserves were First discovered in 1927; the name was changed to the Iraq Petroleum Company

The Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), formerly known as the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC), is an oil company that had a virtual monopoly on all oil exploration and production in Iraq between 1925 and 1961. It was jointly owned by some of the world ...

(IPC) in 1929. It was owned by a consortium of British, French, Dutch and American oil companies, and operated by the British until it was nationalized in 1972. The British ruled under the League mandate from 1918 to 1933. Formal independence was granted in 1933, but with a very powerful British presence in the background.

World War II

Iraq

TheAnglo-Iraqi War

The Anglo-Iraqi War was a British-led Allies of World War II, Allied military campaign during the Second World War against the Kingdom of Iraq, then ruled by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani who had seized power in the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état with assista ...

(2–31 May 1941) was a British military campaign to regain control of Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

and its major oil fields. Rashid Ali

Rashid Ali al-Gaylani (Al-Gailani)in Arab standard pronunciation Rashid Aali al-Kaylani; also transliterated as Sayyid Rashid Aali al-Gillani, Sayyid Rashid Ali al-Gailani or sometimes Sayyad Rashid Ali el Keilany (" Sayyad" serves to address hig ...

had seized power in 1941 with assistance from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. The campaign resulted in the downfall of Ali's government, the re-occupation of Iraq by the British, and the return to power of the Regent of Iraq, Prince Abd al-Ilah

Abd al-Ilah of Hejaz () (; also written Abdul Ilah or Abdullah; 14 November 1913 – 14 July 1958) was a cousin and brother-in-law of King Ghazi of the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq and was regent for his nephew King Faisal II, from 4 April 1939 ...

, a British ally. The British launched a large pro-democracy propaganda campaign in Iraq from 1941–5. It promoted the Brotherhood of Freedom to instil civic pride in disaffected Iraqi youth. The rhetoric demanded internal political reform and warned against growing communist influence. Heavy use was made of the Churchill-Roosevelt Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II, months before the US officially entered the war. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic C ...

. However, leftist groups adapted the same rhetoric to demand British withdrawal. Pro-Nazi propaganda was suppressed. The heated combination of democracy propaganda, Iraqi reform movements, and growing demands for British withdrawal and political reform became as a catalyst for postwar political change.

In 1955, the United Kingdom was part of the Baghdad Pact

The Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), formerly known as the Middle East Treaty Organization (METO) and also known as the Baghdad Pact, was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed on 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey, ...

with Iraq. King Faisal II of Iraq

Faisal II (; 2 May 1935 – 14 July 1958) was the last King of Iraq. He reigned from 4 April 1939 until July 1958, when he was killed during the 14 July Revolution. This regicide marked the end of the thirty-seven-year-old Hashemite monarchy in ...

paid a state visit to Britain in July 1956. The British had a plan to use 'modernisation' and economic growth to solve Iraq's endemic problems of social and political unrest. The idea was that increased wealth through Oil production would ultimately trickle down to all elements and thereby thus stave off the danger of revolution. The oil was produced but the wealth never reached below the elite. Iraq's political-economic system put unscrupulous politicians and wealthy landowners at the apex of power. The remained in control using an all-permeating patronage system. As a consequence very little of the vast wealth was dispersed to the people, and unrest continue to grow. In 1958, monarch and politicians were swept away in a vicious nationalist army revolt.

Suez Crisis of 1956

TheSuez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

of 1956 was a major disaster for British (and French) foreign policy and left Britain a minor player in the Middle East because of very strong opposition from the United States. The key move was an invasion of Egypt in late 1956 first by Israel, then by Britain and France. The aims were to regain Western control of the Suez Canal and to remove Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

, who had just nationalised the canal. After the fighting had started, intense political pressure and economic threats from the United States, plus criticism from the Soviet Union and the United Nations forced a withdrawal by the three invaders. The episode humiliated the United Kingdom and France and strengthened Nasser. The Egyptian forces were defeated, but they did block the canal to all shipping. The three allies had attained a number of their military objectives, but the canal was useless. U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

had strongly warned Britain not to invade; he threatened serious damage to the British financial system by selling the US government's pound sterling bonds. The Suez Canal was closed from October 1956 until March 1957, causing great expense to British shipping interests. Historians conclude the crisis "signified the end of Great Britain's role as one of the world's major powers".

East of Suez

After 1956, the well-used rhetoric of the British role East of Suez was less and less meaningful. The independence of India, Malaya, Burma and other smaller possessions meant London had little role, and few military or economic assets to back it up. Hong Kong was growing in importance but it did not need military force. Labour was in power but both parties agreed on the need to cut the defence budget and redirect attention to Europe and NATO, so the forces were cut east of Suez. David Sanders and David Houghton, ''Losing an empire, finding a role: British foreign policy since 1945'' (2017) pp 118–31.See also

*History of the Middle East

The Middle East, or the Near East, was one of the cradles of civilization: after the Neolithic Revolution and the adoption of agriculture, many of the world's oldest cultures and civilizations were created there. Since ancient times, the Middle ...

* Russia–United Kingdom relations

Russia–United Kingdom relations, also Anglo-Russian relations, are the bilateral relations between the Russian Federation and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Formal ties between the nations started in 1553. Russia and ...

** The Great Game

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations t ...

* Egypt–United Kingdom relations

Egypt–United Kingdom relations are the diplomatic, economic, and cultural relationships between Arab Republic of Egypt, Egypt and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, United Kingdom. Relations are longstanding. They involve ...

* France–United Kingdom relations

The historical ties between France and the United Kingdom, and the countries preceding them, are long and complex, including conquest, wars, and alliances at various points in history. The Roman era saw both areas largely conquered by Rome, ...

* Iran–United Kingdom relations

Iran–United Kingdom relations are the bilateral relations between the United Kingdom and Iran. Iran, which was called Persia by the West before 1935, has had political relations with England since the late Ilkhanate period (13th century) when Edw ...

* Iraq–United Kingdom relations

British–Iraqi relations are foreign relations between Iraq and the United Kingdom.

The current ambassador to Iraq is Stephen Hitchen.

History

The history of British–Iraqi relations date back to the creation of Iraq in 1920, when it was c ...

* Israel–United Kingdom relations

Israel–United Kingdom relations, or Anglo-Israeli relations, are the diplomatic and commercial ties between the United Kingdom and Israel. The Embassy of the United Kingdom, Tel Aviv, British embassy to Israel is located in Tel Aviv. The UK ha ...

* Foreign relations of the Ottoman Empire

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United S ...

* Turkey–United Kingdom relations

The relations between Turkey and the United Kingdom have a long history. The countries have been at war several times, such as within the First World War. They have also been allied several times, such as in the Crimean War. Turkey has an embassy ...

* International relations (1648–1814)

International relations from 1648 to 1814 covers the major interactions of the nations of Europe, as well as the other continents, with emphasis on diplomacy, warfare, migration, and cultural interactions, from the Peace of Westphalia to the Cong ...

** International relations (1814–1919)

This article covers worldwide diplomacy and, more generally, the international relations of the great powers from 1814 to 1919. This era covers the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815), to the end o ...

** Diplomatic history of World War I

The diplomatic history of World War I covers the non-military interactions among the major players during World War I. For the domestic histories of participants see home front during World War I. For a longer-term perspective see international re ...

** International relations (1919–1939)

International relations (1919–1939) covers the main interactions shaping world history in this era, known as the interwar period, with emphasis on diplomacy and economic relations. The coverage here follows the diplomatic history of World War I. ...

** Diplomatic history of World War II

The diplomatic history of World War II includes the major foreign policies and interactions inside the opposing coalitions, the Allies of World War II and the Axis powers, between 1939 and 1945.

High-level diplomacy began as soon as the war start ...

** Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

* Military history of the United Kingdom

The military history of the United Kingdom covers the period from the creation of the united Kingdom of Great Britain, with the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, to the present day.

From the 18th century onwards, with the expansi ...

* United States foreign policy in the Middle East

United States foreign policy in the Middle East has its roots in the early 19th-century First Barbary War, Tripolitan War that occurred shortly after the United States Declaration of Independence, 1776 establishment of the United States as an i ...

Notes

Further reading

* Agoston, Gabor, and Bruce Masters. ''Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire '' (2008) * Anderson, M.S. ''The Eastern Question, 1774-1923: A Study in International Relations'' (1966online

the major scholarly study. * Barr, James. "A Line in the Sand: British-French Rivalry in the Middle East 1915–1948." ''Asian Affairs'' 43.2 (2012): 237–252. * Brenchley, Frank. ''Britain and the Middle East: Economic History, 1945-87'' (1991). * Bullard, Reader. ''Britain and the Middle East from Earliest Times to 1963'' (3rd ed. 1963) * Cleveland, William L., and Martin Bunton. ''A History Of The Modern Middle East'' (6th ed. 201

4th ed. online

* Corbett, Julian Stafford. ''England in the Mediterranean; a study of the rise and influence of British power within the Straits, 1603-1713'' (1904

online

* D'Angelo, Michela. "In the 'English' Mediterranean (1511–1815)." ''Journal of Mediterranean Studies'' 12.2 (2002): 271–285. * Deringil, Selim. "The Ottoman Response to the Egyptian Crisis of 1881-82" ''Middle Eastern Studies'' (1988) 24#1 pp. 3-2

online

* Dietz, Peter. ''The British in the Mediterranean'' (Potomac Books Inc, 1994). * Fieldhouse, D. K. ''Western Imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958'' (Oxford UP, 2006) * Harrison, Robert. ''Britain in the Middle East: 1619-1971'' (2016) short scholarly narrativ

excerpt

* Hattendorf, John B., ed. ''Naval Strategy and Power in the Mediterranean: Past, Present and Future'' (Routledge, 2013). * Holland, Robert. "Cyprus and Malta: two colonial experiences." ''Journal of Mediterranean Studies'' 23.1 (2014): 9–20. * Holland, Robert. ''Blue-water empire: the British in the Mediterranean since 1800'' (Penguin UK, 2012)

excerpt

* Laqueur, Walter. ''The Struggle for the Middle East: The Soviet Union and the Middle East 1958-70'' (1972

online

* Louis, William Roger. ''The British Empire in the Middle East, 1945–1951: Arab Nationalism, the United States, and Postwar Imperialism'' (1984) * MacArthur-Seal, Daniel-Joseph. "Turkey and Britain: from enemies to allies, 1914–1939." ''Middle Eastern Studies'' (2018): 737-743. * Mahajan, Sneh. ''British Foreign Policy 1874-1914: The Role of India'' (2002). * Anderson, M.S. ''The Eastern Question, 1774-1923: A Study in International Relations'' (1966

the major scholarly study. * Marriott, J. A. R. ''The Eastern Question An Historical Study In European Diplomacy'' (1940), Older comprehensive study; more up-to-date is Anderson (1966

Online

* Millman, Richard. ''Britain and the Eastern Question, 1875–1878'' (1979) * Monroe, Elizabeth. ''Britain's moment in the Middle East, 1914-1956'' (1964

online

* Olson, James E. and Robert Shadle, eds., ''Historical dictionary of the British Empire'' (1996) * Owen, Roger. ''Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul'' (Oxford UP, 2005

Online review

On Egypt 1882-1907. * Pack, S.W.C ''Sea Power in the Mediterranean'' – has a complete list of fleet commanders * Panton, Kenneth J. ''Historical Dictionary of the British Empire'' (2015). * Schumacher, Leslie Rogne. "A 'Lasting Solution': the Eastern Question and British Imperialism, 1875-1878." (2012)

online; Detailed bibliography

* Seton-Watson, R. W. ''Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern question; a study in diplomacy and party politics'' (1972

Online

* Seton-Watson, R. W. ''Britain in Europe 1789-1914, a Survey of Foreign Policy'' (1937

Online