Operation Nordmark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Northern Mark () was a sortie by a German

The destroyers , , and together with torpedo boats and screened the German ships as they sailed into the North Sea at but were then sent to the

The destroyers , , and together with torpedo boats and screened the German ships as they sailed into the North Sea at but were then sent to the

The

The

flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' ( fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same cla ...

of two battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s and a heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

against British merchant shipping between Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

and Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

from 18 to 20 February 1940. The sortie was intended as a riposte to the Altmark incident

The ''Altmark'' incident (Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Altmark''-affæren; German language, German: ''Altmark-Zwischenfall'') was a naval incident of World War II between British destroyers and the German tanker German tanker Altma ...

, to create confusion to help German blockade-runners reach home and as a prelude to more ambitious operations in the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

. The flotilla was spotted by the British early on, who held back a Norway-bound convoy.

Battleships of the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

were sent towards the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

to intercept the German ships. The German flotilla found only neutral ships and concluded that they had been found out; British submarine sightings of the flotilla came to nothing amidst stormy weather and confusion over conflicting reports from the submarines. The flotilla returned to base during the afternoon of 20 February; concurrent German U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

patrols sank several ships, including a destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

.

Background

After the British search for theheavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

ended with its destruction, many ships returned to the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

but the German naval war staff () decided that fleet operations were more feasible. The commander of Naval Group West ( ( Alfred Saalwächter

Alfred Saalwächter (10 January 1883 – 6 December 1945) was a high-ranking German U-boat commander during World War I and General Admiral during World War II.

Early life

Saalwächter was born in Neusalz an der Oder, Prussian Silesia, as the ...

) was ordered to conduct more operations with the s and and the heavy cruiser . Admiral Wilhelm Marschall

Wilhelm Marschall (30 September 1886 – 20 March 1976) was a German admiral during World War II. He was also a recipient of the ''Pour le Mérite'' which he received as commander of the U-boat during World War I. The ''Pour le Mérite'' was the ...

was criticised for returning to port after sinking the armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

in November 1939. Attacks were to be made on ships exporting goods from Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

and by disrupting convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s in the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

.

took the view that engine problems in ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' made Atlantic operations too risky and wanted to attack convoys between Bergen

Bergen (, ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, second-largest city in Norway after the capital Oslo.

By May 20 ...

and Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

. wanted to conduct U-boat operations against units of the Home Fleet during another battleship sortie and postponed sailing several times as the icy conditions of the winter of 1939–1940 kept U-boats in port. No intelligence about another Allied convoy sailing had been received and then ''Gneisenau'' was damaged by ice. An operation would also cover the return of the oil tanker

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk cargo, bulk transport of petroleum, oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quant ...

to Germany, since the Germans did not know at the time the tanker was beached. Seven U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s were sent to the northern North Sea to reconnoitre for the German fleet and attack British shipping.

Prelude

On 17 February, the Germans detected a British convoy sailing northwards up the east coast of Britain; another convoy was thought to be nearby and the German operation was ordered for 18 February. Marschall decided that if the German ships were spotted as they left port, he would turn back as soon as it was dark. Because of the weather, Marschall moved the ships fromWilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

into the Wangerooge Channel on the evening of 17 February and during the early morning of 18 February, the British received reports from Bomber Command

Bomber Command is an organisational military unit, generally subordinate to the air force of a country. The best known were in Britain and the United States. A Bomber Command is generally used for strategic bombing (although at times, e.g. during t ...

aircraft that ships appeared to be iced-in near their bases. Patrolling British submarines were redirected as Marschall sailed with ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', ''Admiral Hipper'' and the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s and into the North Sea for Bergen in Norway.

Sortie

The destroyers , , and together with torpedo boats and screened the German ships as they sailed into the North Sea at but were then sent to the

The destroyers , , and together with torpedo boats and screened the German ships as they sailed into the North Sea at but were then sent to the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (; , , ) is a strait running between the North Jutlandic Island of Denmark, the east coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea.

The Skagerrak contains some of the busiest shipping ...

. The destroyer was forced to turn back after suffering damage from ice. With the two remaining destroyers, Marschall headed to and sent seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

s to reconnoitre up to Statlandet further north; no contacts were reported, none being found by other aircraft from Germany either. German signals intelligence was unaware that on 19 February that there was only one eastbound convoy, which had been held back or that the Home Fleet was at sea.

Convoy HN 12 was close to Scotland and the reciprocal ON convoy was sent to Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and Hoy. Its sheltered waters have played an impor ...

until the scare subsided. Ships of the Home Fleet were already at sea covering the attack on ''Altmark'' and reinforcements of battleships were ordered from the River Clyde

The River Clyde (, ) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde, in the west of Scotland. It is the eighth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the second longest in Scotland after the River Tay. It runs through the city of Glasgow. Th ...

to join them. In poor weather, the submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

sent a sighting report that ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'', ''Hipper'' and ''Königsberg'' were heading south at high speed. The SKL wanted Marschall to wait for another day between Shetland and Bergen and agreed with to mount an attack on the ships near Shetland but did not interfere with the operation, rather, tried to influence Marschall by sending frequent reports of British activity,

SKL was against the suggestion but did not intervene; lack of sightings by on 19 February led Marschall to believe that the British had found out about the operation and had suspended convoy sailings; waiting would be pointless and Marschall ordered the ships home. The submarine signalled that a cruiser and two destroyers were heading south-east, which caused much confusion at the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

. Both British submarines were detected and had to submerge deeply to escape, precluding the pursuit of the German ships, then they turned back before reaching U-boat patrol areas. The German ships reached Wilhelmshaven on 20 February as the Home Fleet ships arrived in the North Sea and the Norway-bound ON convoy sailed.

U-boats

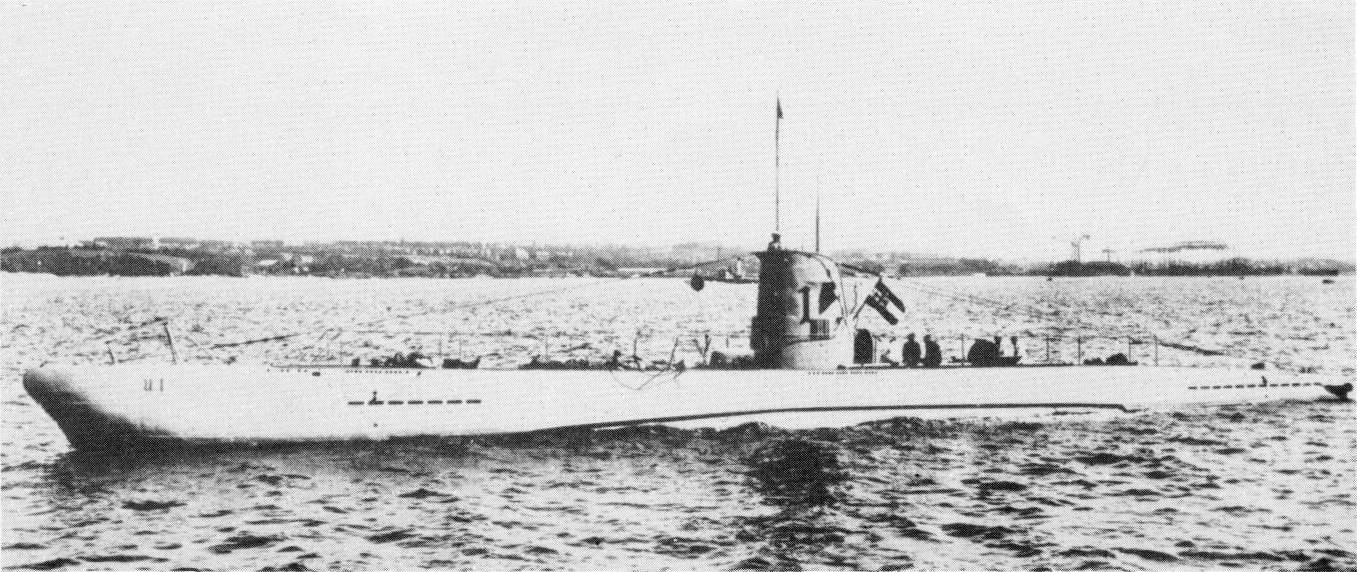

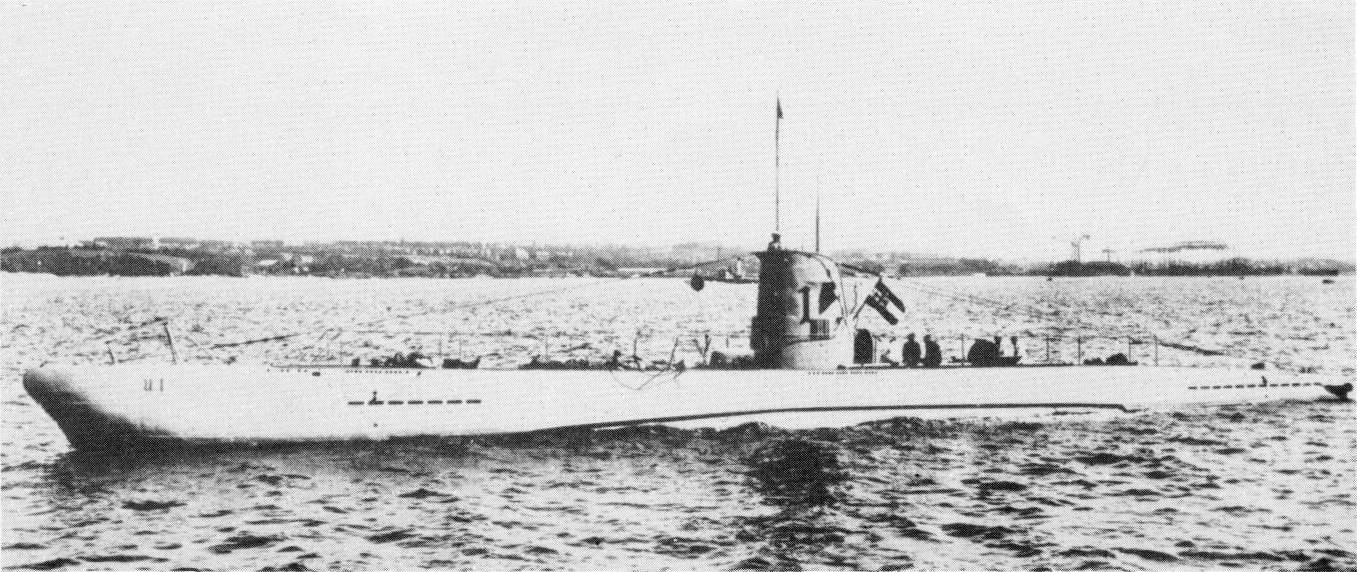

The

The type IIB

In theoretical physics, type II string theory is a unified term that includes both type IIA strings and type IIB strings theories. Type II string theory accounts for two of the five consistent superstring theories in ten dimensions. Both theories ...

U-boat sank a ship of 1,213 gross register tons (GRT) on 11 February off Norway, sank two ships of a total of 6,356 GRT and sank four ships of a total of 5,320 GRT on 15 and 16 February off the Scottish coast. On 21 February ''U-57'' sank a 10,191 GRT ship and damaged a 4,966 GRT straggler east of the Orkney Islands

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland ...

. sank the destroyer which was escorting the west-bound Convoy HN 12 on 18 February, sank a ship on 19 February and on 22 February finished off the 4,966 GRT ship damaged by . sank two ships of a total of 5,703 GRT east of the Shetland Islands

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the Uni ...

and the Orkney Islands on 18 February and sank a 4,211 GRT ship off Kirkwall

Kirkwall (, , or ; ) is the largest town in Orkney, an archipelago to the north of mainland Scotland. First mentioned in the ''Orkneyinga saga'', it is today the location of the headquarters of the Orkney Islands Council and a transport hub wi ...

, Orkney, on 24 February 1940.

Aftermath

SKL was dismayed by the abortive nature of the sortie as they had thought that its prospects were good and decided that the commander of should not limit himself to sending intelligence reports on the position of opposing ships. Orders should be sent to the force commander if he seemed undecided. SKL was not aware of their faulty assessment of the situation and were ignorant of the dispositions made by the British.Grand Admiral

Grand admiral is a historic naval rank, the highest rank in the several European navies that used it. It is best known for its use in Germany as . A comparable rank in modern navies is that of admiral of the fleet.

Grand admirals in individual ...

Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II and was convicted of war crimes after the war. He attained the highest possible naval rank, that of ...

told Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

that the convoy heading north to Kirkwall had kept going. Raeder wanted another operation and thought that better signals intelligence would limit the risks, the Germans still not knowing that the Home Fleet had been in the area and gone unnoticed. Before the next sortie on 25 February, a destroyer flotilla was sent to the Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank ( Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age, the bank was part of a large landmass ...

to attack British trawlers in (Operation Viking) and suffered disaster when one destroyer was sunk by a German Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and medium bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a wolf in sheep's clothing. Due to restrictions placed on Germany a ...

bomber and another destroyer was sunk by a mine. The loss of two destroyers forced a postponement of the next operation; repairs to ''Scharnhorst'' took until 4 march and on 1 March, the directive for the invasion of Denmark and Norway (Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung ( , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was the invasion of Denmark and Norway by Nazi Germany during World War II. It was the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 April 1940 (, "Weser Day"), Ge ...

) had been received, requiring a maximum effort; other operations were indefinitely postponed.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * ** * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Nordmark, Operation North Sea operations of World War II February 1940 in Europe Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Naval battles and operations of the European theatre of World War II