Operation Chariot (1958) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Project Chariot was a 1958

Project Chariot was a 1958

Project Chariot: Nuclear Legacy of Cape Thompson

Proceedings of the U.S. Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee Workshop on Arctic Contamination, Session A: Native People's Concerns about Arctic Contamination II: Ecological Impacts, May 6, 1993, Anchorage, Alaska * Wedman. William, and Charles Diters

The legacy of project Chariot.

Bureau of Indian Affairs, Alaska Region regional archaeology report under the National Historic Preservation Act. Undated, circa 2007.

Project Chariot was a 1958

Project Chariot was a 1958 United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

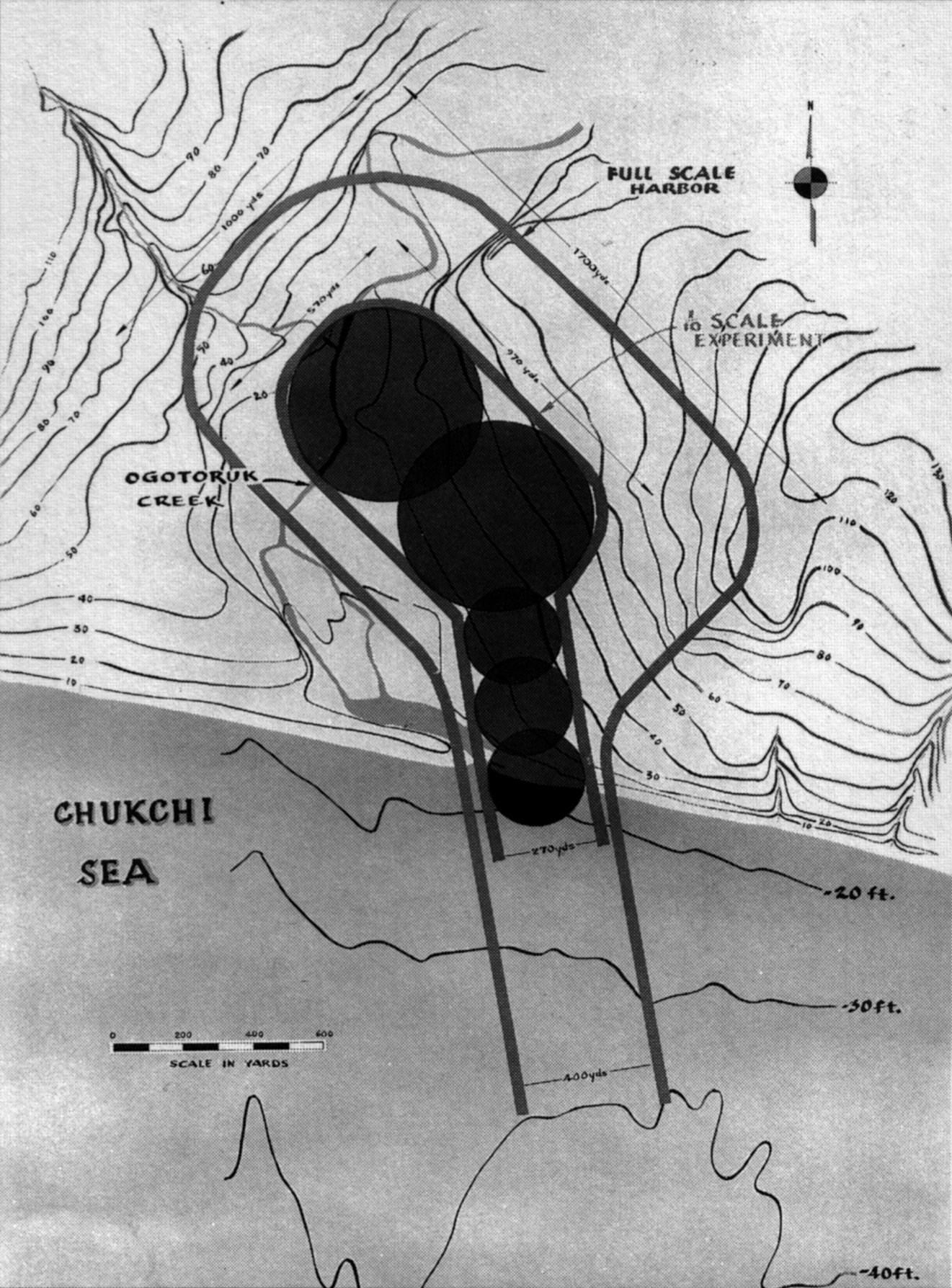

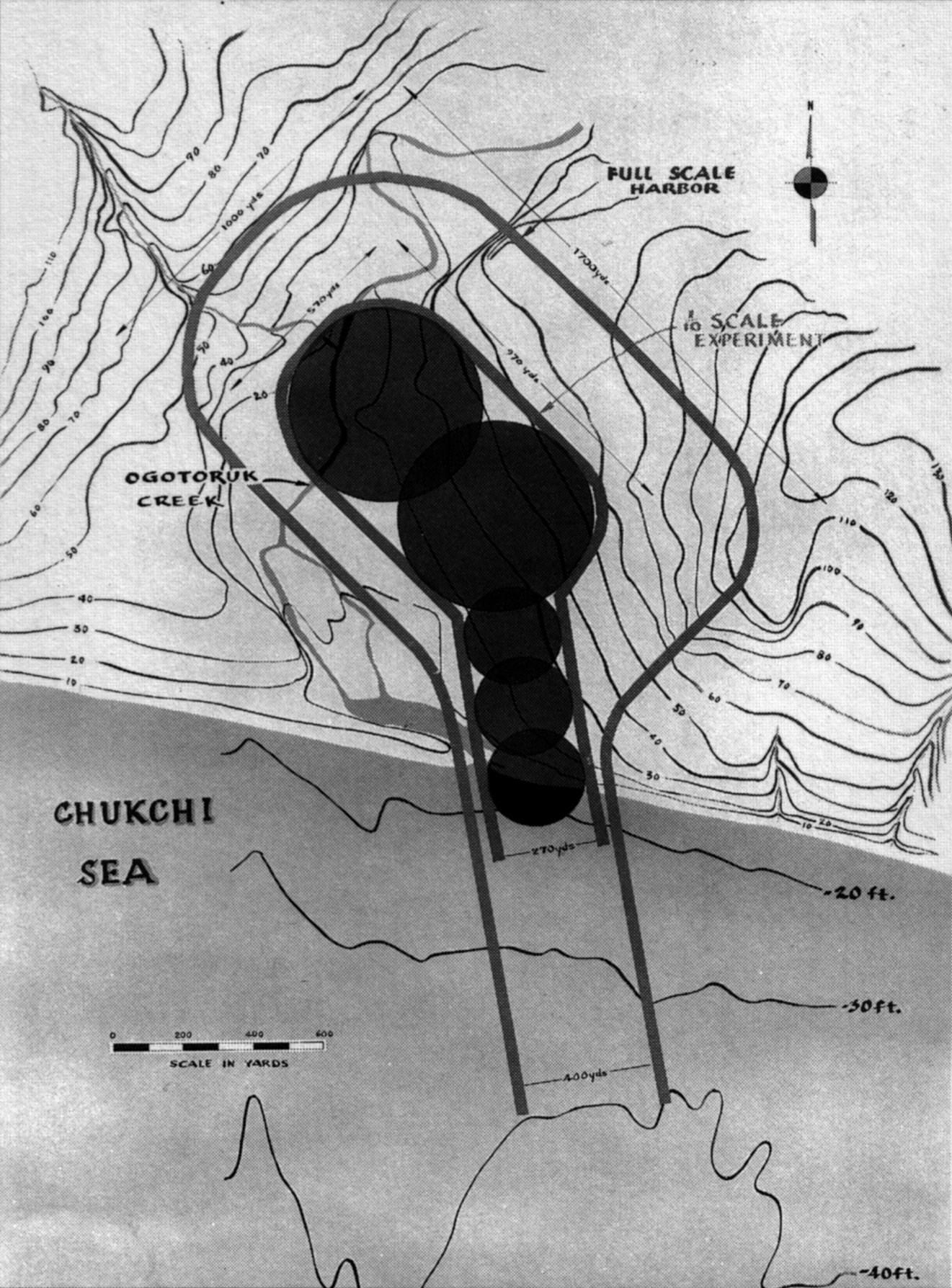

proposal to construct an artificial harbor at Cape Thompson

Cape Thompson is a headland on the Chukchi Sea coast of Alaska. It is located 26 miles (42 km) to the southeast of Point Hope, Arctic Slope. It is part of the Chukchi Sea unit of Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

Early In ...

on the North Slope of the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

by burying and detonating a string of nuclear devices.

The project originated as part of Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. A ...

, a research project to find peaceful uses for nuclear explosives. Substantial local opposition, objections from physical and social scientists engaged in environmental studies, and the absence of any credible economic benefit caused the plan to be quietly shelved.

History

A 1957 meeting at theLawrence Radiation Laboratory

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

(LRL) proposed a program to use nuclear explosives for industrial development projects. This proposal became the basis for Project Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. A ...

, administered by the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

. Chariot was to be the first Plowshare project, and was imagined as a way to show how larger projects, such as a sea-level Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

, or a sea-level Nicaragua Canal, might be accomplished.

The plan was championed by LRL director and nuclear scientist Edward Teller

Edward Teller (; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian and American Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of ...

, who traveled throughout Alaska touting the harbor as an important economic development for America's newest state. Teller promoted a study, contracted by LRL, that proposed development of coal deposits in Northern Alaska. Teller and the LRL proposed the harbor as a port for coal shipment, even though the harbor and surrounding Chukchi Sea would be frozen for nine months of the year. The mines themselves would have been on the far side of the Brooks Range

The Brooks Range (Gwich’in language, Gwich'in: ''Gwazhał'') is a mountain range in far northern North America stretching some from west to east across northern Alaska into Canada's Yukon Territory. Reaching a peak elevation of on Mount Isto, ...

, requiring a railroad and storage facilities for the coal waiting to be shipped.

As the plan developed, relatively small explosions in Nevada, some previously planned, indicated that small blasts could accomplish much of the publicly-stated goals of the project with reduced releases of radioactive contamination. However, as Alaskan business leaders showed there was no economic justification for it, the project shifted to a more clearly avowed program for testing nuclear excavation in a remote location.

Alaskan political leaders, newspaper editors, president William Ransom Wood of the University of Alaska

The University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF or Alaska) is a public land-, sea-, and space-grant research university in College, Alaska, United States, a suburb of Fairbanks. It is the flagship campus of the University of Alaska system. UAF was e ...

, and even church groups all rallied in support of the detonation. Congress had passed the Alaska Statehood Act

The Alaska Statehood Act () was a legislative act introduced by Delegate Bob Bartlett, E. L. "Bob" Bartlett and signed by President of the United States, President Dwight D. Eisenhower on July 7, 1958. Through it, Alaska became the 49th U.S. ...

just a few weeks before. An editorial in the July 24, 1960 ''Fairbanks Daily News-Miner

The '' Fairbanks Daily News-Miner'' is a morning daily newspaper serving the city of Fairbanks, Alaska, the Fairbanks North Star Borough, the Denali Borough, Alaska, Denali Borough, and the Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska, Yukon-Koyukuk Census ...

'' said, "We think the holding of a huge nuclear blast in Alaska would be a fitting overture to the new era which is opening for our state."

Opposition and abandonment

Opposition came from the Inupiaq Alaska Native village of Point Hope, a few scientists engaged in environmental studies under AEC contract, and a handful of conservationists. The grassroots protest soon was picked up by organizations with national reach, such as The Wilderness Society, theSierra Club

The Sierra Club is an American environmental organization with chapters in all 50 U.S. states, Washington, D.C., Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded in 1892, in San Francisco, by preservationist John Muir. A product of the Pro ...

, and Barry Commoner

Barry Commoner (May 28, 1917 – September 30, 2012) was an American cell biology, cellular biologist, college professor, and politician. He was a leading ecologist and among the founders of the modern environmental movement. He was the directo ...

's Committee for Nuclear Information. Repeated visits to the community by AEC officials failed to sway local and Native residents, who opposed land transfers by the Bureau of Land Management

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior responsible for administering federal lands, U.S. federal lands. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the BLM oversees more than of land, or one ...

(BLM) to the AEC. The opposition to Project Chariot that emerged from Point Hope launched a period of Native political organization and activism that led directly to the passage of the landmark Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was signed into law by U.S. President, President Richard Nixon on December 18, 1971, constituting what is still the largest land claims settlement in United States history. ANCSA was intended to reso ...

of 1971.

Internationally, the project drew objections from the Soviet Union, which viewed such projects as a way of circumventing the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT), formally known as the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, prohibited all nuclear weapons testing, test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those co ...

, which was in negotiation at the time.

In 1962, facing increased public uneasiness over the environmental risk and the potential to disrupt the lives of the Alaska Native peoples, the AEC announced that Project Chariot would be "held in abeyance." It has never been formally canceled.

In addition to the objections of the local population, no practical use of such a harbor was ever identified. The environmental studies commissioned by the AEC suggested that radioactive contamination

Radioactive contamination, also called radiological pollution, is the deposition of, or presence of Radioactive decay, radioactive substances on surfaces or within solids, liquids, or gases (including the human body), where their presence is uni ...

from the proposed blast could adversely affect the health and safety of the local people, whose livelihoods were based on the hunting of animals and other subsistence practices. The investigations noted that radiation from worldwide fallout was moving with unusual efficiency up the food chain in the Arctic, from lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

, to caribou

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only represe ...

(which fed on lichen), to humans (for whom caribou was a primary food source). Studies also showed that the blasts would thaw the permafrost

Permafrost () is soil or underwater sediment which continuously remains below for two years or more; the oldest permafrost has been continuously frozen for around 700,000 years. Whilst the shallowest permafrost has a vertical extent of below ...

, making the slopes surrounding the harbor unstable, and negating any experimental value to be gained from using the project as a basis for extrapolation to other, warmer locations. While the AEC publicly touted prevailing winds from the north for dispersing radioactivity over the sea, the AEC privately desired to study landward distribution. The consistent wind patterns would prevent northward fallout patterns over land.

In the meantime, test shots in Nevada provided some data to assist the AEC in modeling excavation scaling and radiation release. The very small 430-ton equivalent Danny Boy test in March 1962 encouraged the AEC to stage the much larger 104-kiloton Sedan test in July 1962. Gerald Johnson, the director of Project Plowshare, described the Sedan test as "an alternative to Chariot" arising from frustration at recommendations for Chariot's cancellation. Fallout from Sedan turned out to be the second-highest of any test in Nevada.

Plan

The project initially envisioned the use of four 100 kiloton devices to excavate a channel, and two one-megaton devices to excavate a turning basin, for a total of 2.4 megatons of explosive equivalent, displacing of earth. Later iterations reduced the explosive total to 480 kilotons, and subsequently a 280 kiloton test or demonstration.Contamination

Although the detonation never occurred, the site was radioactively contaminated by an experiment to estimate the effect on water sources of radioactive ejecta, which, landing on tundra plants, might or might not be washed down and carried away by rains. Material from a 1962 nuclear explosion, and other laboratory-producedradionuclides

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess numbers of either neutrons or protons, giving it excess nuclear energy, and making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ...

, were transported to the Chariot site in August 1962, used in several experiments, then heaped into a pile and covered with dirt (the permafrost preventing burial). The site comprised a mound of about , about tall. Thirty years later, the disposal was discovered in archival documents by University of Alaska researcher Dan O'Neill

Dan O'Neill (born April 21, 1942) is an American underground cartoonist, creator of the syndicated comic strip ''Odd Bodkins'' and founder of the underground comics collective the Air Pirates.

Education

O'Neill attended the University of S ...

. State officials immediately traveled to the site and found low levels of radioactivity at a depth of two feet (60 cm) in the burial mound. Outraged residents of the Inupiat village of Point Hope, who had experienced an unusually high rate of cancer deaths, demanded the removal of the contaminated soil, which the government did at its expense in 1993.

Small-diameter boreholes drilled to measure soil characteristics were remediated in 2014. The five boreholes, drilled in the early 1960s, had used refrigerated diesel fuel as a drilling fluid, contaminating the surrounding area.

See also

* Project Carryall * Project GnomeReferences

Further reading

* * * * Coates, Peter. 'Project Chariot: Alaskan roots of environmentalism'. Alaska History 4/2 (1989), 1-31 * * * Vandegraft, DouglasProject Chariot: Nuclear Legacy of Cape Thompson

Proceedings of the U.S. Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee Workshop on Arctic Contamination, Session A: Native People's Concerns about Arctic Contamination II: Ecological Impacts, May 6, 1993, Anchorage, Alaska * Wedman. William, and Charles Diters

The legacy of project Chariot.

Bureau of Indian Affairs, Alaska Region regional archaeology report under the National Historic Preservation Act. Undated, circa 2007.

External links

* {{Authority control 1958 in AlaskaChariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

Pre-statehood history of Alaska

Chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

Chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...