Old Straight Road on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Old Straight Road, the Straight Road, the Lost Road, or the Lost Straight Road, is

Shippey comments that a ship-burial must have meant "a belief that the desired afterworld was across the western sea", and that Tolkien mirrored this with his "Undying Lands" across the sea from Middle-earth. In short, the ''Beowulf'' poet had "what one can only call an inkling of Tolkien's own image of 'the Lost Straight Road'." He asks who the unnamed beings were, and whether the ship was to sail into the West on a Lost Road to return to them. They are plainly acting on behalf of God; being plural, they cannot be him, but they are supernatural. He suggests that Tolkien considered their nature, as godlike mythological

Shippey comments that a ship-burial must have meant "a belief that the desired afterworld was across the western sea", and that Tolkien mirrored this with his "Undying Lands" across the sea from Middle-earth. In short, the ''Beowulf'' poet had "what one can only call an inkling of Tolkien's own image of 'the Lost Straight Road'." He asks who the unnamed beings were, and whether the ship was to sail into the West on a Lost Road to return to them. They are plainly acting on behalf of God; being plural, they cannot be him, but they are supernatural. He suggests that Tolkien considered their nature, as godlike mythological

J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

's conception, in his fantasy world of Arda

Arda or ARDA may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Arda (Middle-earth), fictional world in the works of J. R. R. Tolkien

* Arda (band), a Russian heavy metal band

People

* Arda (name)

Places

*Arda (Maritsa), a river in Bulgaria and Greece

*A ...

, that his Elves are able to sail to the earthly paradise

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Gene ...

of Valinor

Valinor (Quenya'': Land of the Valar''), the Blessed Realm, or the Undying Lands is a fictional location in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the home of the immortal Valar and Maiar on the continent of Aman, far to the west of Middle-earth; he ...

, realm of the godlike Valar

The Valar (; singular Vala) are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings. They are "angelic powers" or "gods" subordinate to the one God ( Eru Ilúvatar). The '' Ainulindalë'' describes how some of the Ainur choose to enter the ...

. The tale is mentioned in ''The Silmarillion

''The Silmarillion'' () is a book consisting of a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited, partly written, and published posthumously by his son Christopher in 1977, assisted by G ...

'' and in ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high fantasy novel written by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book ''The Hobbit'' but eventually d ...

'', and documented in ''The Lost Road and Other Writings

''The Lost Road and Other Writings – Language and Legend before The Lord of the Rings'' is the fifth volume, published in 1987, of ''The History of Middle-earth'', a series of compilations of drafts and essays written by J. R. R. Tolkien in a ...

''. The Elves are immortal, but may grow weary of the world, and then sail across the Great Sea to reach Valinor. The men of Númenor

Númenor, also called Elenna-nórë or Westernesse, is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings. It was the kingdom occupying a large island to the west of Middle-earth, the main setting of Tolkien's writings, and was the greatest civil ...

are persuaded by Sauron

Sauron () is the title character and the main antagonist of J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'', where he rules the land of Mordor. He has the ambition of ruling the whole of Middle-earth, using the power of the One Ring, which he ...

, servant of the first Dark Lord Melkor

Morgoth Bauglir (; originally Melkor ) is a character, one of the godlike Valar and the primary antagonist of Tolkien's legendarium, the mythic epic published in parts as '' The Silmarillion'', ''The Children of Húrin'', '' Beren and Lúthi ...

, to attack Valinor to get the immortality they feel should be theirs. The Valar ask for help from the creator, Eru Ilúvatar

The fictional cosmology of J.R.R. Tolkien's legendarium combines aspects of Christian theology and metaphysics with pre-modern cosmological concepts in the flat Earth paradigm, along with the modern spherical Earth view of the Solar System.

Th ...

. He destroys Númenor and its army, in the process reshaping Arda into a sphere, and separating it and its continent of Middle-earth

Middle-earth is the Setting (narrative), setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the ''Midgard, Miðgarðr'' of Norse mythology and ''Middangeard'' in Old English works, including ''Beowulf'' ...

from Valinor so that men can no longer reach it. Elves can still set sail from the shores of Middle-earth in ships, bound for Valinor: they sail into the Uttermost West, following the Old Straight Road.

Scholars have noted the importance of the theme to Tolkien, as he revisited it repeatedly. His early mention of the Straight Road as being a level bridge recalls Bifröst

In Norse mythology, Bifröst (modern Icelandic: Bifröst ; from Old Norse: /ˈbiv.rɔst/), also called Bilröst and often anglicized as Bifrost, is a burning rainbow bridge that reaches between Midgard (Earth) and Asgard, the realm of the gods. ...

, the bridge between the earthly Midgard

In Germanic cosmology, Midgard (an anglicised form of Old Norse ; Old English , Old Saxon , Old High German , and Gothic ''Midjun-gards''; "middle yard", "middle enclosure") is the name for Earth (equivalent in meaning to the Greek term : oikou ...

and the gods' home of Asgard

In Nordic mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr''; "Garden of the Æsir") is a location associated with the gods. It appears in several Old Norse sagas and mythological texts, including the Eddas, however it has also been suggested to be refe ...

in Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology, is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia as the Nordic folklore of the modern period. The ...

. Other possible inspirations for the theme include a literary crux in ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poetry, Old English poem, an Epic poetry, epic in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translat ...

'' in the shape of the character Scyld Scefing. He arrives in the world as a baby in a boat filled with gifts, and he departs from it in a ship-burial, with the odd feature that the ship is not set on fire, as in the typical Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

ritual. The scholar Tom Shippey

Thomas Alan Shippey (born 9 September 1943) is a British medievalist, a retired scholar of Middle and Old English literature as well as of modern fantasy and science fiction. He is considered one of the world's leading academic experts on the ...

suggests that Tolkien may have felt that Scyld is being sent back to the gods across the Western sea via a kind of Straight Road, and that Tolkien perhaps created his Valar and their home Valinor to explain that gap in ''Beowulf''. His poem " A Walking Song", which occurs in different versions at the start and end of ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high fantasy novel written by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book ''The Hobbit'' but eventually d ...

'', also alludes to the theme.

Narratives

''The Silmarillion''

In the Second Age of Middle-earth, the godlikeValar

The Valar (; singular Vala) are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings. They are "angelic powers" or "gods" subordinate to the one God ( Eru Ilúvatar). The '' Ainulindalë'' describes how some of the Ainur choose to enter the ...

give the island of Númenor

Númenor, also called Elenna-nórë or Westernesse, is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings. It was the kingdom occupying a large island to the west of Middle-earth, the main setting of Tolkien's writings, and was the greatest civil ...

, in the Great Sea to the West of Middle-earth, to the three loyal houses of Men who had aided the Elves in the war against Morgoth

Morgoth Bauglir (; originally Melkor ) is a character, one of the godlike Vala (Middle-earth), Valar and the primary antagonist of Tolkien's legendarium, the mythic epic published in parts as ''The Silmarillion'', ''The Children of Húrin'', ...

. Through the favour of the Valar, the Dúnedain were granted wisdom, power and longer life, beyond that of other Men. The isle of Númenor lay closer to the Valar's earthly paradise

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Gene ...

of Valinor

Valinor (Quenya'': Land of the Valar''), the Blessed Realm, or the Undying Lands is a fictional location in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the home of the immortal Valar and Maiar on the continent of Aman, far to the west of Middle-earth; he ...

, on the continent of Aman, than to Middle-earth. The fall of Númenor came about through the influence of Sauron

Sauron () is the title character and the main antagonist of J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'', where he rules the land of Mordor. He has the ambition of ruling the whole of Middle-earth, using the power of the One Ring, which he ...

, the chief servant of the fallen Vala Melkor

Morgoth Bauglir (; originally Melkor ) is a character, one of the godlike Valar and the primary antagonist of Tolkien's legendarium, the mythic epic published in parts as '' The Silmarillion'', ''The Children of Húrin'', '' Beren and Lúthi ...

, who wished to conquer Middle-earth.

The Númenóreans took Sauron prisoner. He quickly enthralled their king, Ar-Pharazôn, urging him to seek the immortality that the Valar had apparently denied him. Sauron persuaded them to wage war against the Valar to seize the immortality denied them. Ar-Pharazôn raised the mightiest army and fleet Númenor had ever seen, and sailed to Valinor. The Valar called on the creator, Ilúvatar, for help. When Ar-Pharazôn landed, Ilúvatar destroyed his forces and sent a great wave to submerge Númenor, killing all but those Númenóreans, led by Elendil

Elendil () is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. He is mentioned in ''The Lord of the Rings'', ''The Silmarillion'' and '' Unfinished Tales''. He was the father of Isildur and Anárion, last lord of Andúnië on the islan ...

, who had remained loyal to the Valar, and who escaped to Middle-earth. The world was remade, and Aman was removed beyond the Uttermost West, so that Men could not sail there to threaten it.

The Elves, however, can still sail into the "Uttermost West", on what to Men is the Lost Road to Valinor; Cirdan the Shipwright, at the Grey Havens of Lindon, still builds ships in the Third Age

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the history of Arda, also called the history of Middle-earth, began when the Ainur entered Arda, following the creation events in the Ainulindalë and long ages of labour throughout Eä, the fictional un ...

for Elves who wish to leave Middle-earth. Sauron's physical form was destroyed.

"The Fall of Númenor"

Tolkien wrote "The Fall of Númenor" in 1936. After the island had been drowned and the world remade, the loyal Númenóreans retained a memory of the Old Straight Road, and some tried to build ships that could "rise above the waters of the world and hold to the imagined seas." The "old line of the world" lingered likeTwo unfinished time travel novels

Tolkien made two attempts at a time travel novel, both remaining unfinished: first in the 1936 ''The Lost Road

''The'' is a grammatical article in English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The ...

'', and then in 1945 ''The Notion Club Papers

''The Notion Club Papers'' is an abandoned novel by J. R. R. Tolkien, written in 1945 and published posthumously in ''Sauron Defeated'', the 9th volume of ''The History of Middle-earth''. It is a time travel story, written while ''The Lord of the ...

''. In both of them, he provides a frame story in which a father-and-son pair of modern Englishmen visit past times in dreams, successively going further back until they reach Númenor and discover the story of the Lost Road. In each case, one of the time travellers has a name which means "Elf-friend", tying him directly to the loyal Númenórean Elendil, whose name has the same meaning in the classical Elf-language, Quenya

Quenya ()Tolkien wrote in his "Outline of Phonology" (in '' Parma Eldalamberon'' 19, p. 74) dedicated to the phonology of Quenya: is "a sound as in English ''new''". In Quenya is a combination of consonants, ibidem., p. 81. is a constructed l ...

.

''The Lord of the Rings''

At the end of the main narrative of ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high fantasy novel written by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book ''The Hobbit'' but eventually d ...

'', in the last chapter of ''The Return of the King

''The Return of the King'' is the third and final volume of J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'', following '' The Fellowship of the Ring'' and '' The Two Towers''. It was published in 1955. The story begins in the kingdom of Gondor, ...

'', the protagonist Frodo

Frodo Baggins (Westron: ''Maura Labingi'') is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings and one of the protagonists in ''The Lord of the Rings''. Frodo is a hobbit of Shire (Middle-earth), the Shire who inherits the One Ring from hi ...

, broken by the quest to destroy the One Ring

The One Ring, also called the Ruling Ring and Isildur's Bane, is a central plot element in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'' (1954–55). It first appeared in the earlier story '' The Hobbit'' (1937) as a magic ring that grants the ...

, is allowed to leave Middle-earth, sailing from the Grey Havens over the Sea and out of the world on the Straight Road to find peace in Valinor. He is able to do so, as a mortal Hobbit

Hobbits are a fictional race of people in the novels of J. R. R. Tolkien. About half average human height, Tolkien presented hobbits as a variety of humanity, or close relatives thereof. Occasionally known as halflings in Tolkien's writings, ...

, because the Elf Arwen

Arwen Undómiel is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. She appears in the novel ''The Lord of the Rings''. Arwen is one of the half-elven who lived during the Third Age; her father was Elrond half-elven, lor ...

has given him her place; she has chosen to marry a mortal man, King Aragorn

Aragorn () is a fictional character and a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. Aragorn is a Ranger of the North, first introduced with the name Strider and later revealed to be the heir of Isildur, an ancient King of ...

, and so to die from the world as men do.

There are two versions of " A Walking Song" in the novel, one near the beginning of the book when Frodo is just setting out, not knowing where his quest may lead, one in the last chapter. Especially in the second, when he knows he will soon leave Middle-earth, Frodo sings of "the hidden paths that run / West of the Moon, East of the Sun". The verse alludes to his coming journey on the Straight Road, the wording subtly changed to be more definite, even final:

Analysis

Cosmology

In Tolkien's conception, Arda was created specifically as the place forElves

An elf (: elves) is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology, being mentioned in the Icelandic ''Poetic Edda'' and the ''Prose Edda''.

In medieval Germanic-speakin ...

and Men

A man is an adult male human. Before adulthood, a male child or adolescent is referred to as a boy.

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromosome from the fa ...

to live in. It is envisaged in a flat Earth

Flat Earth is an archaic and scientifically disproven conception of the Figure of the Earth, Earth's shape as a Plane (geometry), plane or Disk (mathematics), disk. Many ancient cultures, notably in the cosmology in the ancient Near East, anci ...

cosmology, with the stars, and later also the sun and moon, revolving around it. Tolkien's legendarium

Tolkien's legendarium is the body of J. R. R. Tolkien's mythopoeic writing, unpublished in his lifetime, that forms the background to his ''The Lord of the Rings'', and which his son Christopher summarized in his compilation of '' The Silma ...

addresses the spherical Earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of the figure of the Earth as a sphere. The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Ancient Greek philos ...

paradigm by depicting a catastrophic transition from a flat to a spherical world, the Akallabêth

''The Silmarillion'' () is a book consisting of a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited, partly written, and published posthumously by his son Christopher in 1977, assisted by G ...

, in which Valinor becomes inaccessible to mortal Men. All that is left is the memory of the old straight road, or the tale of the Elves able to travel by it. When Men die, they leave the world of Arda entirely, perhaps to go to a heaven. Elves, on the other hand, cannot leave "the circles of the world", and are constrained to go to Valinor, or, if they die in battle, to the Halls of Mandos, from where they may be allowed to return to Valinor. Tolkien stated that "the passage over Sea is not Death. The 'mythology' is Elf-centred. According to it there was at first an actual Earthly Paradise, home and realm of the Valar, as a physical part of the earth."

Major theme

Because of the evil implanted by Sauron in the minds of the men ofNúmenor

Númenor, also called Elenna-nórë or Westernesse, is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings. It was the kingdom occupying a large island to the west of Middle-earth, the main setting of Tolkien's writings, and was the greatest civil ...

, the world became bent, so men could no longer sail the Straight Road westwards to Valinor

Valinor (Quenya'': Land of the Valar''), the Blessed Realm, or the Undying Lands is a fictional location in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the home of the immortal Valar and Maiar on the continent of Aman, far to the west of Middle-earth; he ...

. Tom Shippey

Thomas Alan Shippey (born 9 September 1943) is a British medievalist, a retired scholar of Middle and Old English literature as well as of modern fantasy and science fiction. He is considered one of the world's leading academic experts on the ...

writes that Tolkien's personal First World War experience was Manichean: evil seemed at least as powerful as good, and could easily have been victorious, a strand which can also be seen in Middle-earth.

The image of the Straight Road was, Shippey writes, evidently important to Tolkien, as he revisited it repeatedly in his legendarium. The two time travel novels both foundered on the problem that while they made perfect sense to him as frame stories, which he worked out in some detail, this was at the expense of their actual narratives, which he never got around to writing.

Verlyn Flieger

Verlyn Flieger (born 1933) is an author, editor, and Professor Emerita in the Department of English at the University of Maryland at College Park, where she taught courses in comparative mythology, medieval literature, and the works of J. R. R. To ...

writes that Tolkien's essay " ''Beowulf'': the Monsters and the Critics", his " On Fairy-Stories", and ''The Lost Road'' all indicate his "desire to pass through that open door into Other Time." She adds that ''The Lost Road'' illustrated his "vision of the lost paradise and the longing to return to it" which "became a more and more powerful element in his later fiction", forming eventually the "underpinning" of ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high fantasy novel written by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book ''The Hobbit'' but eventually d ...

''.

Stuart D. Lee and Elizabeth Solopova state that the stories of the variously named time-travelling Eriol/Ǽlfwine, ''The Lost Road'', and ''The Notion Club Papers'' should be seen as fragments of a single-purposed attempt by Tolkien to form a unified story. This places the events of the Silmarillion (legendarium) as part of the history or prehistory of the Earth, many thousand years ago. A central event in that story is the reshaping of the world, leaving only the Straight Road as the way to the earthly paradise. They quote Christopher Tolkien

Christopher John Reuel Tolkien (21 November 1924 – 16 January 2020) was an English and naturalised French academic editor and writer. The son of the author and academic J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher edited 24 volumes based on his father's P ...

's explanation in ''The Lost Road and Other Writings'':

Scyld Scefing

''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poetry, Old English poem, an Epic poetry, epic in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translat ...

'', an Anglo-Saxon poem that Tolkien knew well, contains, among its crux

CRUX is a lightweight x86-64 Linux distribution targeted at experienced Linux users and delivered by a tar.gz-based package system with BSD-style initscripts. It is not based on any other Linux distribution. It also utilizes a ports system ...

es, its unexplained or problematic passages, a mention of Scyld Scefing at the start. This, Shippey notes, has several odd features, making it the kind of thing that attracted Tolkien's interest. "Scefing" looks like a patronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (more specifically an avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor. It is the male equivalent of a matronymic.

Patronymics are used, b ...

, but cannot be as Scyld's father is not known. It could equally mean "with a sheaf

Sheaf may refer to:

* Sheaf (agriculture), a bundle of harvested cereal stems

* Sheaf (mathematics)

In mathematics, a sheaf (: sheaves) is a tool for systematically tracking data (such as sets, abelian groups, rings) attached to the open s ...

", evidently a symbol. When Scyld dies, he is given a ship burial, being placed in a ship supplied with many gifts for his one-way journey into the afterlife. However, and uniquely for a Viking ship burial, the ship is not set on fire, so in practical terms the ship would surely, Shippey writes, have been looted. Dimitra Fimi

Dimitra Fimi (born 2 June 1978) is a Greek academic and writer. She became the Professor of Fantasy and Children's Literature at the University of Glasgow in 2023. Her field of research includes the writings of J. R. R. Tolkien and children's fa ...

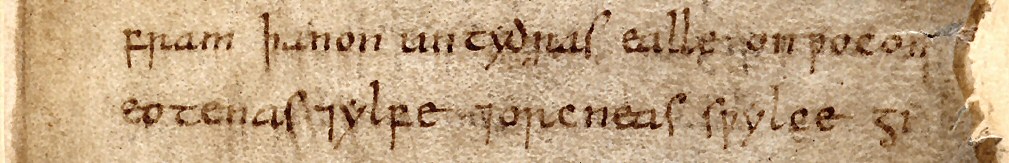

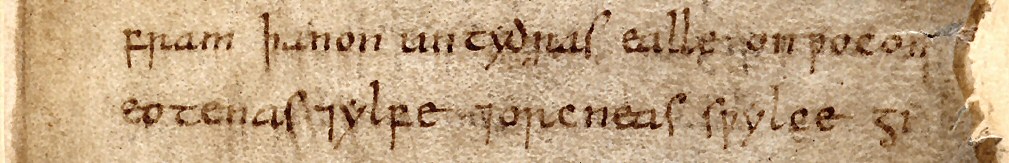

notes that ''Beowulf'' (lines 26–52) describes Scyld's funeral ship sailing "on its own accord" to its unknown harbour.

The cosmology of this story is not explained, beyond the cryptic statement that "those" had sent Scyld as a baby into the world. Shippey notes that the pronoun

In linguistics and grammar, a pronoun (Interlinear gloss, glossed ) is a word or a group of words that one may substitute for a noun or noun phrase.

Pronouns have traditionally been regarded as one of the part of speech, parts of speech, but so ...

("those") is, unusually for such an insignificant part of speech, both stressed and alliterated, a heavy emphasis (marked in the text):

In ''The Lost Road and Other Writings

''The Lost Road and Other Writings – Language and Legend before The Lord of the Rings'' is the fifth volume, published in 1987, of ''The History of Middle-earth'', a series of compilations of drafts and essays written by J. R. R. Tolkien in a ...

'', Christopher Tolkien

Christopher John Reuel Tolkien (21 November 1924 – 16 January 2020) was an English and naturalised French academic editor and writer. The son of the author and academic J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher edited 24 volumes based on his father's P ...

quotes from one of his father's lectures: "the 'Beowulf''poet is not explicit, and the idea was probably not fully formed in his mind—that Scyld went back to some mysterious land whence he had come. He came out of the Unknown beyond the Great Sea, and returned into It". Tolkien explains that "the symbolism (what we should call the ritual) of a departure over the sea whose further shore was unknown; and an actual belief in a magical land or otherworld located 'over the sea', can hardly be distinguished."

Shippey comments that a ship-burial must have meant "a belief that the desired afterworld was across the western sea", and that Tolkien mirrored this with his "Undying Lands" across the sea from Middle-earth. In short, the ''Beowulf'' poet had "what one can only call an inkling of Tolkien's own image of 'the Lost Straight Road'." He asks who the unnamed beings were, and whether the ship was to sail into the West on a Lost Road to return to them. They are plainly acting on behalf of God; being plural, they cannot be him, but they are supernatural. He suggests that Tolkien considered their nature, as godlike mythological

Shippey comments that a ship-burial must have meant "a belief that the desired afterworld was across the western sea", and that Tolkien mirrored this with his "Undying Lands" across the sea from Middle-earth. In short, the ''Beowulf'' poet had "what one can only call an inkling of Tolkien's own image of 'the Lost Straight Road'." He asks who the unnamed beings were, and whether the ship was to sail into the West on a Lost Road to return to them. They are plainly acting on behalf of God; being plural, they cannot be him, but they are supernatural. He suggests that Tolkien considered their nature, as godlike mythological demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the Demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. Various sects of Gnostics adopted the term '' ...

s, and that this perhaps prompted him to create the Valar, given that Tolkien habitually "deriv dinspiration from a philological crux", for instance inventing Elves, Ettens, and Orc

An orc (sometimes spelt ork; ), in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth fantasy fiction, is a race of humanoid monsters, which he also calls "goblin".

In Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'', orcs appear as a brutish, aggressive, ugly, and malevol ...

s from a line in ''Beowulf''.

Further to ''Beowulf'' account of Scyld and his strange departure, Tolkien wrote a poem, " King Sheave", on the Scyld Scefing theme. Sheave is the father of Beow ("Barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

"), making him a corn-god. He is lost from his bed, but found again alive and well outside, recalling Christ

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Christianity, central figure of Christianity, the M ...

's empty tomb and his being found alive, walking in a garden. The reign of King Sheave is described as "the Golden Years", linking him to Fróði Fróði (; ; Middle High German: ''Vruote'') is the name of a number of legendary Danish kings in various texts including ''Beowulf'', Snorri Sturluson's ''Prose Edda'' and his ''Ynglinga saga'', Saxo Grammaticus' ''Gesta Danorum'', and the ''Gro ...

of the ''Poetic Edda

The ''Poetic Edda'' is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems in alliterative verse. It is distinct from the closely related ''Prose Edda'', although both works are seminal to the study of Old Norse ...

'', who is also a Christ-figure. Tolkien makes the connection with the time-travellers and Elendil, by having the Sheave story told by Ælfwine

Ælfwine (also ''Aelfwine'', ''Elfwine'') is an Old English personal name. It is composed of the elements ''ælf'' "elf" and ''wine'' "friend", continuing a hypothetical Common Germanic given name ''*albi- winiz'' which is also continued in Old Hig ...

in the Anglo-Saxon King Alfred

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when ...

's hall.

Bifröst

Elizabeth Whittingham

Elizabeth Whittingham is a former lecturer in English at the State University of New York College, Brockport, New York. She is known for her Tolkien studies research, including her 2008 book ''The Evolution of Tolkien's Mythology'', which examine ...

comments that the "level bridge" of "The Fall of Númenor" reminds readers of Bifröst

In Norse mythology, Bifröst (modern Icelandic: Bifröst ; from Old Norse: /ˈbiv.rɔst/), also called Bilröst and often anglicized as Bifrost, is a burning rainbow bridge that reaches between Midgard (Earth) and Asgard, the realm of the gods. ...

in Norse mythology, the rainbow bridge that links Midgard

In Germanic cosmology, Midgard (an anglicised form of Old Norse ; Old English , Old Saxon , Old High German , and Gothic ''Midjun-gards''; "middle yard", "middle enclosure") is the name for Earth (equivalent in meaning to the Greek term : oikou ...

and Asgard

In Nordic mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr''; "Garden of the Æsir") is a location associated with the gods. It appears in several Old Norse sagas and mythological texts, including the Eddas, however it has also been suggested to be refe ...

. The level bridge "imperceptibly" departs from the earth at a tangent, but enough of the earlier cosmology remains "in the mind of the Gods" for the Elves and the Valar to be able to travel that Straight Road. John Garth similarly states that while the Straight Road linking Valinor with Middle-Earth after the Second Age mirrors Bifröst, the Valar themselves resemble the Æsir

Æsir (Old Norse; singular: ) or ēse (Old English; singular: ) are deities, gods in Germanic paganism. In Old Nordic religion and Nordic mythology, mythology, the precise meaning of the term "" is debated, as it can refer either to the gods i ...

, the gods of Asgard.

Garth notes further that two central figures in poems that Tolkien knew, Väinämöinen

() is a deity, demigod, hero and the central character in Finnish folklore and the main character in the national epic ''Kalevala'' by Elias Lönnrot. Väinämöinen was described as an old and wise man, and he possessed a potent, magical sing ...

in the Finnish ''Kalevala

The ''Kalevala'' () is a 19th-century compilation of epic poetry, compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology, telling a story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies and retaliatory ...

'', and Hiawatha in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to comp ...

's ''The Song of Hiawatha

''The Song of Hiawatha'' is an 1855 epic poem in trochaic tetrameter by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow which features Native American characters. The epic relates the fictional adventures of an Ojibwe warrior named Hiawatha and the tragedy of his lo ...

'', both leave the world in boats, sailing off into the sky, as the Elves do when following the Old Straight Road into the West. The protagonist of the first piece of Tolkien's legendarium, Eärendel, similarly sails a ship out of Arda into the sky. His ship carries the last of the Silmarils

The Silmarils (Quenya in-universe , )J. R. R. Tolkien, Tolkien, J. R. R., "Addenda and Corrigenda to the Etymologies — Part Two" (edited by Carl F. Hostetter and Patrick H. Wynne), in ''Vinyar Tengwar'', 46, July 2004, p. 11 are three ficti ...

, shining brilliantly as the Evening Star.

Other inspirations

Fimi comments that Tolkien seemed to be intending to use his translation of the Anglo-Saxon poem " The Seafarer" to express "Ælfwine's desire to sail upon the western sea and find the 'Straight Road', the 'Lost Road' that leads to Valinor and the Elves even after the world is 'bent'." Norma Roche, writing in ''Mythlore

''Mythlore'' is a biannual (originally quarterly) peer-reviewed academic journal founded by Glen GoodKnight and published by the Mythopoeic Society. Although it publishes articles that explore the genres of myth and fantasy in general, special a ...

'', notes the parallels between Valinor and the Celtic island paradise described in the story of St Brendan

Brendan of Clonfert (c. AD 484 – c. 577) is one of the early Celtic Christianity, Irish monastic saints and one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. He is also referred to as Brendan the Navigator, Brendan the Voyager, Brendan the Anchorite, ...

, and that Tolkien wrote a poem named "Imram", named after the immram

An immram (; plural immrama; , 'voyage') is a class of Old Irish tales concerning a hero's sea journey to the Otherworld (see Tír na nÓg and Mag Mell). Written in the Christian era and essentially Christian in aspect, they preserve elemen ...

genre of Irish tradition, for ''The Notion Club Papers''. Fimi was surprised that Tolkien apparently linked immram in the shape of St. Brendan's voyages to Ælfwine's journey into the uttermost West, and went on doing so. All the same, she notes the parallels between "the Western happy otherworld island and the geography and function of Valinor", commenting that the Celtic otherworld

In Celtic mythology, the Otherworld is the realm of the Celtic deities, deities and possibly also the dead. In Gaels, Gaelic and Celtic Britons, Brittonic myth it is usually a supernatural realm of everlasting youth, beauty, health, abundance an ...

derives from the earthly paradise, the Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Ge ...

, of the Bible.

Legacy

Ursula Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin ( ; Kroeber; October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018) was an American author. She is best known for her works of speculative fiction, including science fiction works set in her Hainish universe, and the ''Earthsea'' fantas ...

's ''Earthsea

''The Earthsea Cycle'', also known as ''Earthsea'', is a series of high fantasy books written by American author Ursula K. Le Guin. Beginning with '' A Wizard of Earthsea'' (1968), '' The Tombs of Atuan'', (1970) and '' The Farthest Shore'' (1 ...

'' series has been described as directly influenced by Tolkien. The Tolkien scholar David Bratman David Bratman is a librarian and Tolkien scholar.

Biography

Bratman was born in Chicago to Robert Bratman, a physician, and his wife Nancy, an editor. He was one of four sons in the family. He was brought up in Cleveland, Ohio, and then in Cali ...

writes that there is a recurring theme of locale in her fantasy stories, especially in her 1985 novel, ''Always Coming Home

''Always Coming Home'' is a 1985 science fiction novel by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin. It is in parts narrative, pseudo-textbook and pseudo-anthropologist's record. It describes the life and society of the Kesh people, a cultural group ...

''. In that work, she named a path which roughly tracks California highway 29 as "The Old Straight Road". Bratman states that the story conveys "a sense of a mythology" of the region.

References

Primary

Secondary

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Middle-earth Middle-earth theology