Olaus Murie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

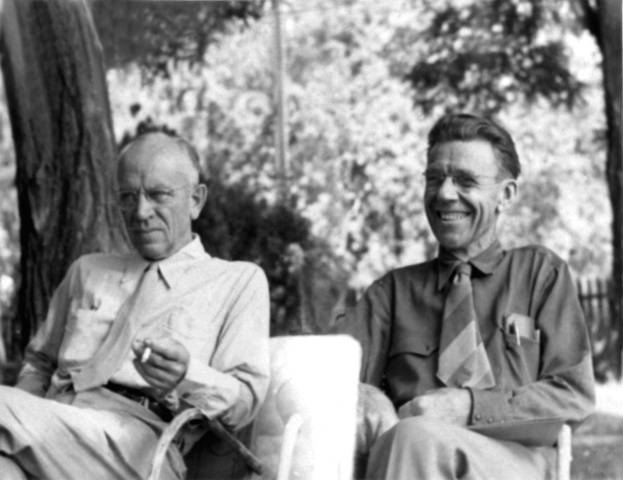

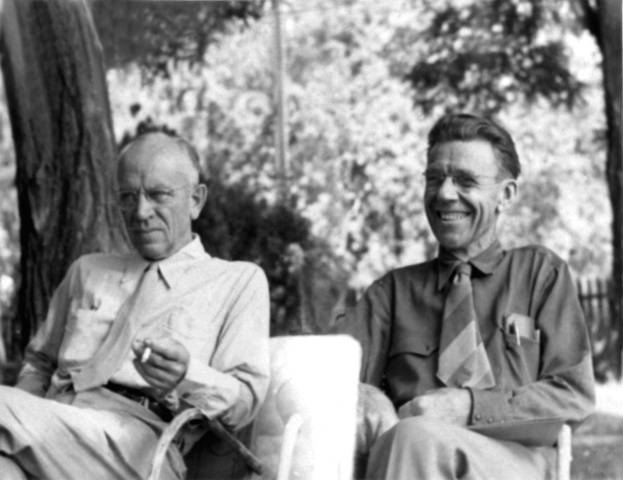

Olaus Johan Murie (March 1, 1889 – October 21, 1963), called the "father of modern elk management",

U.S. National Park Service website: ParkWise > Teachers > Culture > Living in Kenai Fjords was a naturalist, author, and wildlife biologist who did groundbreaking field research on a variety of large northern mammals. Rather than conducting empirical experiments, Murie practiced a more observational-based science. Murie focused his research on the North American continent by conducting vast studies throughout Canada, Alaska and Wyoming. Through these constructive yet sometimes treacherous trips, Murie was able to gain valuable experience observing species and collecting specimens. During his first expedition to Canada, Murie discovered his passion for fieldwork and was able to develop resourceful skills from his indigenous guides, which were critical for his survival in such a harsh environment. Murie employed many of these same skills as he travelled to Alaska and finally to Wyoming. These trips served as the foundation for many of his key ideas about wildlife management and conservation. As a scientist of the U.S. Biological Survey, Murie developed key ideas concerning predator prey relationships. Generally unheard of during his time, Murie argued that a healthy predator population was key to ensuring a harmonious balance between predator and prey populations. Murie used these ideas to improve current wildlife management practices. Throughout his life, Murie advocated on behalf of wildlife conservation and management. With his wife, Mardie Murie, he successfully campaigned to enlarge the boundaries of the

Pugsley Medal biography of Murie He began his career as an Oregon State conservation officer and participated in scientific explorations of Hudson Bay and Labrador, financed by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Museum. He joined the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) in 1920 as a wildlife biologist, spending the next 6 years in the field with his brother

In 1937, Murie accepted a council seat on the recently created Wilderness Society. In this role, Murie lobbied successfully against the construction of large federal dams within Glacier National Park,

In 1937, Murie accepted a council seat on the recently created Wilderness Society. In this role, Murie lobbied successfully against the construction of large federal dams within Glacier National Park,

Murie Center web site

LCCN Alaska-Yukon caribou

* ''Food Habits of the Coyote in Jackson Hole, Wyoming'' (1935) * ''Field Guide to Animal Tracks'' (1954) * ''Fauna of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula'' (NAF No. 61, 1959) * ''Jackson Hole with a Naturalist'' (1963) * ''Wapiti Wilderness'' * ''National Leaders of American Conservation'' Stroud, Richard H., ed. (1984); Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. * "The Joys of Solitude and Nature: Naturalist finds fulfillment in Wilderness" ''Life Magazine'' (1959); 47(26), December 28. * ''Living Wilderness (Summer–Fall, 1963)'' * Little, John J. (October 2000). "A Wilderness Apprenticeship: Olaus Murie in Canada, 1914–15 and 1917". ''Environmental History'' 5 (4) *

The Murie Center

Inventory of the Murie Family Papers

at the

Digital collection of the Murie Family

a

AHC Digital Collections

Blog posts of the Murie Family

a

AHC blogs

* See material on Hudson Bay and Labrador-Ungava Expeditions at Library and Archives Canada

{{DEFAULTSORT:Murie, Olaus 1889 births 1963 deaths People from Moorhead, Minnesota American people of Norwegian descent Pacific University alumni John Burroughs Medal recipients People from Moose, Wyoming University of Michigan alumni Sierra Club awardees 20th-century American naturalists

U.S. National Park Service website: ParkWise > Teachers > Culture > Living in Kenai Fjords was a naturalist, author, and wildlife biologist who did groundbreaking field research on a variety of large northern mammals. Rather than conducting empirical experiments, Murie practiced a more observational-based science. Murie focused his research on the North American continent by conducting vast studies throughout Canada, Alaska and Wyoming. Through these constructive yet sometimes treacherous trips, Murie was able to gain valuable experience observing species and collecting specimens. During his first expedition to Canada, Murie discovered his passion for fieldwork and was able to develop resourceful skills from his indigenous guides, which were critical for his survival in such a harsh environment. Murie employed many of these same skills as he travelled to Alaska and finally to Wyoming. These trips served as the foundation for many of his key ideas about wildlife management and conservation. As a scientist of the U.S. Biological Survey, Murie developed key ideas concerning predator prey relationships. Generally unheard of during his time, Murie argued that a healthy predator population was key to ensuring a harmonious balance between predator and prey populations. Murie used these ideas to improve current wildlife management practices. Throughout his life, Murie advocated on behalf of wildlife conservation and management. With his wife, Mardie Murie, he successfully campaigned to enlarge the boundaries of the

Olympic National Park

Olympic National Park is a national park of the United States located in Washington, on the Olympic Peninsula. The park has four regions: the Pacific coastline, alpine areas, the west-side temperate rainforest, and the forests of the drier e ...

, and to create the Jackson Hole National Monument

On March 15, 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Presidential Proclamation 2578 establishing a large swath of land east of the Teton National Park as a national monument.Booklet of the Congressional hearing to abolish the Jackson Hole national Monu ...

and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR, pronounced as “''ANN-warr''”) or Arctic Refuge is a national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska, United States, on traditional Inupiaq, Iñupiaq and Gwichʼin, Gwich'in lands. The refuge is of ...

. During his career, Murie held many respected positions within environmental organizations. He served as president of The Wilderness Society, The Wildlife Society

The Wildlife Society (TWS) is an international non-profit association involved in wildlife stewardship through science and education. The Wildlife Society works to improve wildlife conservation in North America by advancing the science of wildlif ...

, and as director of the Izaak Walton League

The Izaak Walton League of America, Inc. is an American environmental organization founded in 1922 that promotes natural resource protection and outdoor recreation. The organization was founded in Chicago, Illinois, by a group of sportsmen who wi ...

.

Early life

Murie was born on March 1, 1889, inMoorhead, Minnesota

Moorhead ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Clay County, Minnesota, Clay County, Minnesota, United States, on the banks of the Red River of the North. Located in the Red River Valley, an extremely fertile and active agricultural region, Moo ...

, the child of Norwegian immigrants. Growing up in this less urbanized region helped foster a love for the wilderness from an early age. Murie studied biology at Fargo College

Fargo College was a coeducational institution in Fargo, North Dakota.

History

Fargo College was founded in 1888 under the auspices of the Congregational Church. At the close of 1919, there were 32 professors and instructors, and 602 students. The ...

, private liberal arts college of the Congregational Church. When his zoology professor moved to Pacific University

Pacific University is a private university in Forest Grove, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1849 as the Tualatin Academy, the original Forest Grove campus is west of Portland. Affiliated with the United Church of Christ, the school mainta ...

in Oregon, he offered Murie a scholarship to transfer there, where he completed studies in zoology and wildlife biology and was graduated in 1912. He did graduate work at the University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

and was granted an M.S.

A Master of Science (; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree. In contrast to the Master of Arts degree, the Master of Science degree is typically granted for studies in sciences, engineering and medicine ...

in 1927.Pugsley Medal biography of Murie He began his career as an Oregon State conservation officer and participated in scientific explorations of Hudson Bay and Labrador, financed by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Museum. He joined the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) in 1920 as a wildlife biologist, spending the next 6 years in the field with his brother

Adolph Murie

Adolph Murie (September 6, 1899 – August 16, 1974), the first scientist to study wolves in their natural habitat, was a naturalist, author, and wildlife biologist who pioneered field research on wolves, bears, and other mammals and birds in Arct ...

, studying Alaskan caribou, mapping migratory routes and estimating numbers. He married Margaret Thomas in 1924 in Anvik, Alaska

Anvik (Deg Xinag: ) is a city, home to the Deg Hit'an people, in the Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska, United States. The name Anvik, meaning "exit" in the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, became the common usage despite multiple names at the ...

. They spent their honeymoon tracking caribou through the Koyukuk River

The Koyukuk River (; ''Ooghekuhno' '' in Koyukon, ''Kuuyukaq'' or ''Tagraġvik'' in Iñupiaq) is a tributary of the Yukon River, in the U.S. state of Alaska. It is the last major tributary entering the Yukon before the larger river empties int ...

region.

Books and articles

In 1927, the Biological Survey assigned Murie to research theJackson Hole

Jackson Hole (originally called Jackson's Hole by mountain men) is a valley between the Gros Ventre Range, Gros Ventre and Teton Range, Teton mountain ranges in the U.S. state of Wyoming, near the border with Idaho, in Teton County, Wyoming, T ...

elk herd, resulting in the classic publication ''The Elk of North America.'' He also authored six other major publications, including ''Alaska-Yukon Caribou'' (North American Fauna AFNo. 54, 1935); ''Food Habits of the Coyote in Jackson Hole, Wyoming'' (1935); ''Field Guide to Animal Tracks'' (1954); ''Fauna of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula'' (NAF No. 61, 1959); and ''Jackson Hole with a Naturalist'' (1963). ''Wapiti Wilderness'' (with his wife, Mardy Murie) was published posthumously, in 1966.

Research, service, and wildlife organizations

Research

Canada

One of Murie’s first experiences collecting specimens and conducting research was in 1914–1915 and 1917 in Canada. Hired by W. E. Clyde Todd, the curator of birds at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and accompanied by Native American guides Paul Commanda, William Morrison and Jack (Jocko) Couchai, Murie embarked on his apprenticeship to study wildlife in Canada in 1914. While on this trip, Murie had numerous jobs and expectations. Murie was responsible for collecting bird, rodent and larger mammal specimens, as well as sketching and taking photographs of different organisms and environments. To do so, Murie was required to preserve and label not only animal skins but also rolls of film that was to be given to Carnegie Museum. During his time in Canada, Olaus Murie travelled to various locations and became accustomed to the harsh environment of the Arctic. Murie decided to stay an extra winter in Canada to gain more experience, despite the departure of his colleagues. Murie used this additional time to collect more animal samples as well as explore the ecological and cultural similarities and differences of the Hudsonian and Arctic life zones. Two years later, Murie returned to Canada with Clyde Todd, Alfred Marshall, a wealthy businessman, and guides Paul Commanda, Philip St. Onge and Charles Volant. The trip was ambitious, as they proposed to travel 700 miles north across Labrador, an expedition that had never been done before. They began by following the Ste. Marguerite River until they reached the Labrador Plateau, which they were required to trek across to access the Moisie River. Eventually they reached the Hamilton River and finally Ungava Bay and their destination, Fort Chimo. Although the trip was not without its trials, especially when they were unsure of the correct direction of their destination, it was a success overall for amassing specimens. In total 1,862 specimens were collected, which represented 141 species of birds and 30 species of mammals. Murie’s time in Canada provided him with skills needed for a lifetime working in wildlife biology. Because of the pristine and relatively untouched conditions of the arctic due to the lack of humans, Murie was able to establish a more holistic understanding of humans’ impact on an environment, which he would develop more in subsequent trips around North America.Alaska

In 1920, following his work in Canada, Murie accepted a position working for the U.S. Biological Survey in Alaska, studying the caribou in Alaska to locate the largest caribou populations, with the intention of crossbreeding them with reindeer. Murie was also expected to collect specimens of various animals, and act as a Fur Warden by enforcing laws that protected animals against illegal fur trade practices. Murie was also encouraged to ensure large caribou populations in the region. To do so, one practice employed by the U.S. Biological Survey during this time was predator poisoning, which reduced predator populations in order to increase prey species. However, the more Murie studied caribou populations, the more he opposed this idea.] Although Murie at first was not extremely vocal in his opposition, he began to express his views. He remarked, “I have a theory that a certain amount of preying on caribou by wolves is beneficial to the herd, that the best animal survive and the vigor of the herd is maintained. Man's killing does not work in this natural way, as the best animals are shot and inferior animals left to breed. I think that good breeding’s as important in game animals as it is in domestic stock. With our game, however we have been accustomed to reverse the process killing off the finest animals and removing the natural enemies which tend to keep down the unfit.” Murie saw that hunting by humans was counter to trends produced by nature, and counteracted Darwin’ssurvival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

. He believed the true cause of a reduction in elk populations was not wolves, but rather human economic drive. Murie believed that the “caribou’s greatest menace is not the wolf nor the hunter but man's economic development, principally the raising of reindeer”. Murie observed that elk, along with other wild species, needed ample land to survive. Thus, to ensure a specie’s survival, Murie argued that preservation of its habitat was necessary.

While Murie was critical of his own agency’s ways, it was not until later in his life that he became more outspoken in his views. Besides allowing Murie to formulate his own ideas towards conservation, his time in Alaska gave him additional experience working in the field and resulted in more recognition for him in the realm of field biology.]

Wyoming

In 1927, after his time in Alaska, Murie was hired by the National Elk Commission to determine the cause of the elk winterkill problem in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. As the chief field biologist, Murie concluded that human development was causing overcrowding in the elk’s winter range. Murie was one of the first to discover that these elk historically resided in the mountains and not solely in the plains thus contributing to overcrowding. Although a National Elk Refuge existed in this region consisting of 4,500 acres, this refuge had some unexpected consequences. Due to supplemental feeding and a rougher browse, elk were developing bacterial lesions in their throat and mouth called necrotic stomatitis or calf diphtheria. The Hordeum jubatum, squirrel-tail grass seeds found on the refuge contributed to the irritation of these lesions and the close proximity of elk allowed for the bacteria to spread easily. Through these observations, Murie determined that protecting the elk’s habitat initially, would have been more beneficial than attempting to mitigate the problem later.New Zealand

Due to Murie's extensive knowledge of elk in their native habitat, he was shoulder-tapped by Colonel John K. Howard to be the scientific leader of the 1949 New Zealand American Fiordland Expedition. Murie's son, Donald, was also part of the 49-strong expedition team, who spent January to May 1949 inFiordland National Park

Fiordland National Park is a national park in the south-west corner of South Island of New Zealand. It is the largest of the 13 National parks of New Zealand, national parks in New Zealand, with an area covering , and a major part of the Te W� ...

. The main aim of the expedition was to study the elk (wapiti) population that had been established in the park in 1905, but the large interdisciplinary team also comprised New Zealand biologists from other fields in zoology, botany, geology, and forest survey, as well as surveyors and photographers.''''

Service and wildlife organizations

In 1937, Murie accepted a council seat on the recently created Wilderness Society. In this role, Murie lobbied successfully against the construction of large federal dams within Glacier National Park,

In 1937, Murie accepted a council seat on the recently created Wilderness Society. In this role, Murie lobbied successfully against the construction of large federal dams within Glacier National Park, Dinosaur National Monument

Dinosaur National Monument is an American national monument located on the southeast flank of the Uinta Mountains on the border between Colorado and Utah at the confluence of the Green River (Colorado River tributary), Green and Yampa River, Y ...

, Rampart Dam

The Rampart Dam or Rampart Canyon Dam was a project proposed in 1954 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to dam the Yukon River in Alaska for Hydroelectricity, hydroelectric power. The project was planned for Rampart Canyon (also known as Ramp ...

on Alaska’s Yukon River

The Yukon River is a major watercourse of northwestern North America. From its source in British Columbia, it flows through Canada's territory of Yukon (itself named after the river). The lower half of the river continues westward through the U.S ...

and the Narrows Dam proposed for the mouth of Snake River Canyon.

Murie helped to enlarge existing national park boundaries and to create additional new units. Testimony on the boundaries of Olympic National Park

Olympic National Park is a national park of the United States located in Washington, on the Olympic Peninsula. The park has four regions: the Pacific coastline, alpine areas, the west-side temperate rainforest, and the forests of the drier e ...

helped to convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt to add the temperate rain forest of the Bogachiel River

The Bogachiel River () is a river of the Olympic Peninsula in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. It originates near Bogachiel Peak, and flows westward through the mountains of Olympic National Park. After emerging from the park it ...

and Hoh Rain Forest

Hoh Rainforest is one of the largest temperate rainforests in the U.S., located on the Olympic Peninsula in western Washington state. It encompasses of low elevation forest along the Hoh River, ranging from . The rainforest receives an averag ...

in the Hoh River

The Hoh River is a river of the Pacific Northwest, located on the Olympic Peninsula in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. About long, the Hoh River originates at the snout of Hoh Glacier on Mount Olympus (Washington), Mount Olym ...

valley. Lobbying for a natural boundary for the elk of the Grand Teton

Grand Teton is the highest mountain of the Teton Range in Grand Teton National Park at in Northwest Wyoming. Below its north face is Teton Glacier.

The mountain is a classic destination in American mountaineering via the Owen-Spalding rout ...

area, Murie helped to create Jackson Hole National Monument

On March 15, 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Presidential Proclamation 2578 establishing a large swath of land east of the Teton National Park as a national monument.Booklet of the Congressional hearing to abolish the Jackson Hole national Monu ...

in 1943 (it was upgraded to national park status several years later, then incorporated into the Grand Teton National Park

Grand Teton National Park is a national park of the United States in northwestern Wyoming. At approximately , the park includes the major peaks of the Teton Range as well as most of the northern sections of the valley known as Jackson Hole. G ...

). The Jackson Hole National Monument was especially near to his heart because he had studied the elk in this region for a long period of time. Before it was distinguished as a national park, Murie and others encouraged John D. Rockefeller, Jr to purchase the land and donate it to the federal government. During this time Murie was unaware that Rockefeller intended to create " a wildlife display" so tourists could easily view wild animals without actually putting in much effort. Murie greatly opposed this measure, believing that it would actually reduce the value and appreciation of nature by making it so available and convenient for people. In his article "Fenced Wildlife for Jackson Hole" he stated that "commercialized recreation has tend more and more to make us crave extra service, easy entertainment, pleasure with the least possible exertion." He believed instead that "national parks were created for preservation in their primitive conditions."

Once the park was established in 1943, Murie was appointed as the head of the Wildlife Management Division of the National Park Service and was in charge of creating a management plan for the monument. Despite protest from local sportsmen, Murie banned hunting within the national park. Even when the state of Wyoming, in the case ''State of Wyoming V Franke'', claimed that the additional land held no archeological, scientific or scenic interest, Murie stood by the decision to deem it a national park. He maintained that the park had biological significance with countless species of birds and mammals that lived within the park. Although in the end the court announced it could not interfere in the matter, conservationists such as Murie interpreted this as a win for their side.

With a new position as Director of the Wilderness Society, Murie would continue to fight for and defend existing national parks. Murie relied on techniques that stressed the economic value of national preservation sites because he knew this was the most effective way to appeal to America’s public. For instance, in the case of Jackson Hole National Monument, he emphasized how new tourism was contributing to Jackson's local economy. Murie would go on to advocate for the preservation of many additional parks from human development. He believed that those who wished to "seek the solitude of the primitive forest" should have the ability to do so and that a democratic society should protect this right.

In 1956, Murie began a campaign with his wife to protect what is now the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR, pronounced as “''ANN-warr''”) or Arctic Refuge is a national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska, United States, on traditional Inupiaq, Iñupiaq and Gwichʼin, Gwich'in lands. The refuge is of ...

. The couple recruited U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1975. Douglas was known for his strong progressive and civil libertari ...

to help persuade President Dwight Eisenhower to set aside as the Arctic National Wildlife Range.

Awards, honors

In 1948, Murie became the firstAmerican

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

Fulbright Scholar

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States cultural exchange programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the peopl ...

in New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

and conducted research in the Fiordland National Park

Fiordland National Park is a national park in the south-west corner of South Island of New Zealand. It is the largest of the 13 National parks of New Zealand, national parks in New Zealand, with an area covering , and a major part of the Te W� ...

, acting as scientific leader in the 1949 New Zealand American Fiordland Expedition. In 1950, Murie became president of The Wilderness Society. He was also a president of the Wildlife Society

The Wildlife Society (TWS) is an international non-profit association involved in wildlife stewardship through science and education. The Wildlife Society works to improve wildlife conservation in North America by advancing the science of wildlif ...

and a director of the Izaak Walton League

The Izaak Walton League of America, Inc. is an American environmental organization founded in 1922 that promotes natural resource protection and outdoor recreation. The organization was founded in Chicago, Illinois, by a group of sportsmen who wi ...

. He received the Aldo Leopold

Aldo Leopold (January 11, 1887 – April 21, 1948) was an American writer, Philosophy, philosopher, Natural history, naturalist, scientist, Ecology, ecologist, forester, Conservation biology, conservationist, and environmentalist. He was a profes ...

Memorial Award Medal in 1952, the Pugsley Medal in 1953, Pugsley Medal – Recipients 1928–1964 the Audubon Medal

The National Audubon Society (Audubon; ) is an American non-profit environmental organization dedicated to conservation of birds and their habitats. Located in the United States and incorporated in 1905, Audubon is one of the oldest of such orga ...

in 1959, and the Sierra Club John Muir Award in 1962.

Olaus Murie died on October 21, 1963. The Murie Residence in Moose, Wyoming

Moose is an unincorporated community in Teton County, Wyoming, in the Jackson Hole valley. It has a US Post Office, with the zip code of 83012. The town is located within Grand Teton National Park along the banks of the Snake River. It is popula ...

was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

in 1990, and as part of the Murie Ranch Historic District was designated a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

in 2006. The house and grounds are the headquarters for the Murie Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to conservation work.Murie Center web site

References

Footnotes

Sources

* ''Journeys to the Far North'' * ''The Elk of North America'' * ''Alaska-Yukon Caribou'' (North American Fauna AFNo. 54, 1935LCCN Alaska-Yukon caribou

* ''Food Habits of the Coyote in Jackson Hole, Wyoming'' (1935) * ''Field Guide to Animal Tracks'' (1954) * ''Fauna of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula'' (NAF No. 61, 1959) * ''Jackson Hole with a Naturalist'' (1963) * ''Wapiti Wilderness'' * ''National Leaders of American Conservation'' Stroud, Richard H., ed. (1984); Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. * "The Joys of Solitude and Nature: Naturalist finds fulfillment in Wilderness" ''Life Magazine'' (1959); 47(26), December 28. * ''Living Wilderness (Summer–Fall, 1963)'' * Little, John J. (October 2000). "A Wilderness Apprenticeship: Olaus Murie in Canada, 1914–15 and 1917". ''Environmental History'' 5 (4) *

External links

The Murie Center

Inventory of the Murie Family Papers

at the

American Heritage Center

The American Heritage Center is the University of Wyoming's repository of manuscripts, rare books, and the university archives. Its collections focus on Wyoming and the Rocky Mountain West (including politics, settlement, Native Americans, and W ...

Digital collection of the Murie Family

a

AHC Digital Collections

Blog posts of the Murie Family

a

AHC blogs

* See material on Hudson Bay and Labrador-Ungava Expeditions at Library and Archives Canada

{{DEFAULTSORT:Murie, Olaus 1889 births 1963 deaths People from Moorhead, Minnesota American people of Norwegian descent Pacific University alumni John Burroughs Medal recipients People from Moose, Wyoming University of Michigan alumni Sierra Club awardees 20th-century American naturalists