Norman Foster Ramsey Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norman Foster Ramsey Jr. (August 27, 1915 – November 4, 2011) was an American physicist who was awarded the 1989 Nobel Prize in Physics, for the invention of the separated oscillatory field method, which had important applications in the construction of atomic clocks. A physics professor at Harvard University for most of his career, Ramsey also held several posts with such government and international agencies as NATO and the United States Atomic Energy Commission. Among his other accomplishments are helping to found the United States Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory and Fermilab.

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of Brooklyn, New York, and accepted a teaching position at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The two expected to spend the rest of their lives there, but World War II intervened. In September 1940 the British Tizard Mission brought a number of new technologies to the United States, including a cavity magnetron, a high-powered device that generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of Brooklyn, New York, and accepted a teaching position at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The two expected to spend the rest of their lives there, but World War II intervened. In September 1940 the British Tizard Mission brought a number of new technologies to the United States, including a cavity magnetron, a high-powered device that generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student Daniel Kleppner developed the atomic hydrogen maser, looking to increase the accuracy with which the hyperfine separations of atomic hydrogen, deuterium and tritium could be measured, as well as to investigate how much the hyperfine structure was affected by external magnetic and electric fields. He also participated in developing an extremely stable clock based on a hydrogen maser. From 1967 until 2019, the second has been defined based on 9,192,631,770 hyperfine transition of a cesium-133 atom; the atomic clock which is used to set this standard is an application of Ramsey's work. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1989 "for the invention of the separated oscillatory fields method and its use in the hydrogen maser and other atomic clocks". The Prize was shared with Hans G. Dehmelt and

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student Daniel Kleppner developed the atomic hydrogen maser, looking to increase the accuracy with which the hyperfine separations of atomic hydrogen, deuterium and tritium could be measured, as well as to investigate how much the hyperfine structure was affected by external magnetic and electric fields. He also participated in developing an extremely stable clock based on a hydrogen maser. From 1967 until 2019, the second has been defined based on 9,192,631,770 hyperfine transition of a cesium-133 atom; the atomic clock which is used to set this standard is an application of Ramsey's work. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1989 "for the invention of the separated oscillatory fields method and its use in the hydrogen maser and other atomic clocks". The Prize was shared with Hans G. Dehmelt and

"Proton–Proton Scattering at 105 MeV and 75 MeV"

Harvard University, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the United States Atomic Energy Commission), (January 31, 1951). *Ramsey, N. F.; Cone, A. A.; Chen, K. W.; Dunning, J. R. Jr.; Hartwig, G.; Walker, J. K. & R. Wilson

"Inelastic Scattering Of Electrons By Protons"

Department of Physics at Harvard University, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the United States Atomic Energy Commission), (December 1966). *Greene, G. L.; Ramsey, N. F.; Mampe, W.; Pendlebury, J. M.; Smith, K. ; Dress, W. B.; Miller, P. D. & P. Perrin

"Determination of the Neutron Magnetic Moment"

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Harvard University, Institut Laue–Langevin, Astronomy Centre of

Group photograph

taken at ''Lasers'' '93 including (right to left) Norman F. Ramsey, Marlan Scully, and

Norman Ramsey, an oral history conducted in 1995 by Andrew Goldstein, IEEE History Center, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Papers relating to the Manhattan Project, 1945–1946, collected by Norman Ramsey

Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Libraries, from SIRIS * including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1989 ''Experiments with Separated Oscillatory Fields and Hydrogen Masers'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Ramsey, Norman Foster 1915 births 2011 deaths Columbia College (New York) alumni Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Columbia University faculty Harvard University faculty Nobel laureates in Physics National Medal of Science laureates American Nobel laureates IEEE Medal of Honor recipients Vannevar Bush Award recipients Manhattan Project people Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences American physicists People associated with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki University of Michigan staff Fellows of the American Physical Society Presidents of the American Physical Society Members of the American Philosophical Society

Early life

Norman Foster Ramsey Jr. was born in Washington, D.C., on August 27, 1915, to Minna Bauer Ramsey, an instructor at the University of Kansas, and Norman Foster Ramsey, a 1905 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point and an officer in the Ordnance Department who rose to the rank of brigadier general during World War II, commanding the Rock Island Arsenal. He was raised as anArmy brat

A military brat ( colloquial or military slang) is a child of serving or retired military personnel. Military brats are associated with a unique subcultureDavid C. Pollock, Ruth E. van Reken. ''Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds'', Revi ...

, frequently moving from post to post, and lived in France for a time when his father was Liaison Officer with the ''Direction d'Artillerie'' and Assistant Military Attaché

A military attaché is a military expert who is attached to a diplomatic mission, often an embassy. This type of attaché post is normally filled by a high-ranking military officer, who retains a commission while serving with an embassy. Opport ...

. This allowed him to skip a couple of grades along the way, so that he graduated from Leavenworth High School in Leavenworth, Kansas

Leavenworth () is the county seat and largest city of Leavenworth County, Kansas, United States and is part of the Kansas City metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 37,351. It is located on the west bank of t ...

, at the age of 15.

Ramsey's parents hoped that he would go to West Point, but at 15, he was too young to be admitted. He was awarded a scholarship to the University of Kansas, but in 1930 his father was posted to Governors Island, New York. Ramsey therefore entered Columbia University in 1931, and began studying engineering. He became interested in mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, and switched to this as his academic major. By the time he received his BA from Columbia in 1935, he had become interested in physics. Columbia awarded him a Kellett Fellowship

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhattan ...

to Cambridge University where he studied physics at Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named ...

under Lord Rutherford and Maurice Goldhaber, and encountered notable physicists including Edward Appleton, Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German physicist and mathematician who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics and supervised the work of a n ...

, Edward Bullard, James Chadwick, John Cockcroft, Paul Dirac, Arthur Eddington

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He was also a philosopher of science and a populariser of science. The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the lumin ...

, Ralph Fowler

Sir Ralph Howard Fowler (17 January 1889 – 28 July 1944) was a British physicist and astronomer.

Education

Fowler was born at Roydon, Essex, on 17 January 1889 to Howard Fowler, from Burnham, Somerset, and Frances Eva, daughter of George De ...

, Mark Oliphant and J.J. Thomson. At Cambridge, he took the tripos in order to study quantum mechanics, which had not been covered at Columbia, resulting in being awarded a second BA degree by Cambridge.

A term paper Ramsey wrote for Goldhaber on magnetic moments caused him to read recent papers on the subject by Isidor Isaac Rabi, and this stimulated an interest in molecular beam A molecular beam is produced by allowing a gas at higher pressure to expand through a small orifice into a chamber at lower pressure to form a beam of particles (atoms, free radicals, molecules or ions) moving at approximately equal velocities, with ...

s, and in doing research for a PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

under Rabi at Columbia. Soon after Ramsey arrived at Columbia, Rabi invented molecular beam resonance spectroscopy, for which he was awarded the Nobel prize in physics in 1944. Ramsey was part of Rabi's team that also included Jerome Kellogg

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

, Polykarp Kusch, Sidney Millman and Jerrold Zacharias

Jerrold Reinach Zacharias (January 23, 1905 – July 16, 1986) was an American physicist and Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as an education reformer. His scientific work was in the area of nuclear physics ...

. Ramsey worked with them on the first experiments making use of the new technique, and shared with Rabi and Zacharias in the discovery that the deuteron was a magnetic quadrupole. This meant that the atomic nucleus was not spherical, as had been thought. He received his PhD in physics from Columbia in 1940, and became a fellow at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C., where he studied neutron-proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

and proton- helium scattering

Scattering is a term used in physics to describe a wide range of physical processes where moving particles or radiation of some form, such as light or sound, are forced to deviate from a straight trajectory by localized non-uniformities (including ...

.

World War II

Radiation laboratory

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of Brooklyn, New York, and accepted a teaching position at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The two expected to spend the rest of their lives there, but World War II intervened. In September 1940 the British Tizard Mission brought a number of new technologies to the United States, including a cavity magnetron, a high-powered device that generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of Brooklyn, New York, and accepted a teaching position at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The two expected to spend the rest of their lives there, but World War II intervened. In September 1940 the British Tizard Mission brought a number of new technologies to the United States, including a cavity magnetron, a high-powered device that generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

, which promised to revolutionize radar. Alfred Lee Loomis of the National Defense Research Committee established the Radiation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to develop this technology. Ramsey was one of the scientists recruited by Rabi for this work.

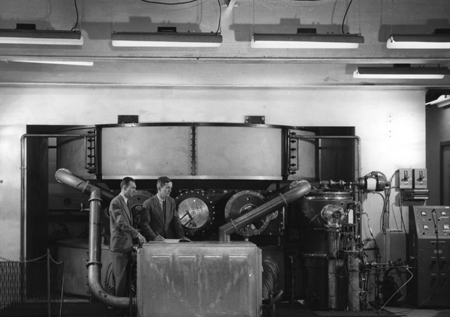

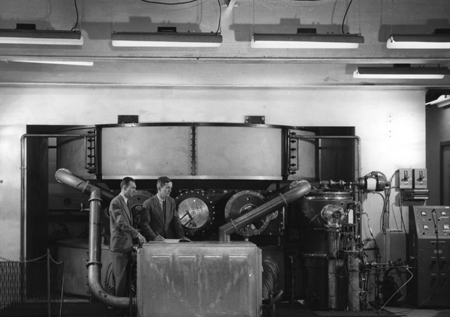

Initially, Ramsey was in Rabi's magnetron group. When Rabi became a division head, Ramsey became the group leader. The role of the group was to develop the magnetron to permit a reduction in wavelength from to , and then to or X-Band. Microwave radar promised to be small, lighter and more efficient than older types. Ramsey's group started with the design produced by Oliphant's team in Britain, and attempted to improve it. The Radiation Laboratory produced the designs, which were prototyped by Raytheon, and then tested by the laboratory. In June 1941, Ramsey travelled to Britain, where he met with Oliphant, and the two exchanged ideas. He brought back some British components which were incorporated into the final design. A night fighter aircraft, the Northrop P-61 Black Widow, was designed around the new radar. Ramsey returned to Washington in late 1942 as an adviser on the use of the new 3 cm microwave radar sets that were now coming into service, working for Edward L. Bowles

Edward is an English language, English given name. It is derived from the Old English, Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements ''wikt:ead#Old English, ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and ''wikt:weard#Old English, weard'' "gua ...

in the office of the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson.

Manhattan Project

In 1943, Ramsey was approached by Robert Oppenheimer andRobert Bacher

Robert Fox Bacher (August 31, 1905November 18, 2004) was an American nuclear physicist and one of the leaders of the Manhattan Project. Born in Loudonville, Ohio, Bacher obtained his undergraduate degree and doctorate from the University of Mich ...

, who asked him to join the Manhattan Project. Ramsey agreed to do so, but the intervention of the Project director, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves Jr., was necessary in order to prise him away from the Secretary of War's office. A compromise was agreed to, whereby Ramsey remained on the payroll of the Secretary of War, and was merely seconded to the Manhattan Project. In October 1943, Group E-7 of the Ordnance Division was created at the Los Alamos Laboratory with Ramsey as group leader, with the task of integrating the design and delivery of the nuclear weapons being built by the laboratory.

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

aircraft large enough: the British Avro Lancaster

The Avro Lancaster is a British Second World War heavy bomber. It was designed and manufactured by Avro as a contemporary of the Handley Page Halifax, both bombers having been developed to the same specification, as well as the Short Stirlin ...

and the US Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) wanted to use the B-29 if at all possible, even though it required substantial modification. Ramsey supervised the test drop program, which began at Dahlgren, Virginia, in August 1943, before moving to Muroc Dry Lake, California, in March 1944. Mock ups of Thin Man and Fat Man bombs were dropped and tracked by an SCR-584 ground-based radar set of the kind that Ramsey had helped develop at the Radiation laboratory. Numerous problems were discovered with the bombs and the aircraft modifications, and corrected.

Plans for the delivery of the weapons in combat were assigned to the Weapons Committee, which was chaired by Ramsey, and answerable to Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

William S. Parsons

Rear Admiral William Sterling "Deak" Parsons (26 November 1901 – 5 December 1953) was an American naval officer who worked as an ordnance expert on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He is best known for being the weaponeer on the ''En ...

. Ramsey drew up tables of organization and equipment for the Project Alberta detachment that would accompany the USAAF's 509th Composite Group

The 509th Composite Group (509 CG) was a unit of the United States Army Air Forces created during World War II and tasked with the operational deployment of nuclear weapons. It conducted the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in ...

to Tinian. Ramsey briefed the 509th's commander, Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the '' Enola Gay'' (named after his mot ...

, on the nature of the mission when the latter assumed command of the 509th. Ramsey went to Tinian with the Project Alberta detachment as Parsons's scientific and technical deputy. He was involved in the assembly of the Fat Man bomb, and relayed Parsons's message indicating the success of the bombing of Hiroshima to Groves in Washington, D.C.

Research

At the end of the war, Ramsey returned to Columbia as a professor and research scientist. Rabi and Ramsey picked up where they had left off before the war with their molecular beam experiments. Ramsey and his first graduate student,William Nierenberg

William Aaron Nierenberg (February 13, 1919 – September 10, 2000) was an American physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project and was director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography from 1965 through 1986. He was a co-founder of the Ge ...

, measured various nuclear magnetic dipole and electric quadrupole

A quadrupole or quadrapole is one of a sequence of configurations of things like electric charge or current, or gravitational mass that can exist in ideal form, but it is usually just part of a multipole expansion of a more complex structure ref ...

moments. With Rabi, he helped establish the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

. In 1946, he became the first head of the Physics Department there. His time there was brief, for in 1947, he joined the physics faculty at Harvard University, where he would remain for the next 40 years, except for brief visiting professorships at Middlebury College

Middlebury College is a private liberal arts college in Middlebury, Vermont. Founded in 1800 by Congregationalists, Middlebury was the first operating college or university in Vermont. The college currently enrolls 2,858 undergraduates from all ...

, Oxford University, Mt. Holyoke College and the University of Virginia. During the 1950s, he was the first science adviser to NATO, and initiated a series of fellowships, grants and summer school programs to train European scientists.

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student Daniel Kleppner developed the atomic hydrogen maser, looking to increase the accuracy with which the hyperfine separations of atomic hydrogen, deuterium and tritium could be measured, as well as to investigate how much the hyperfine structure was affected by external magnetic and electric fields. He also participated in developing an extremely stable clock based on a hydrogen maser. From 1967 until 2019, the second has been defined based on 9,192,631,770 hyperfine transition of a cesium-133 atom; the atomic clock which is used to set this standard is an application of Ramsey's work. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1989 "for the invention of the separated oscillatory fields method and its use in the hydrogen maser and other atomic clocks". The Prize was shared with Hans G. Dehmelt and

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student Daniel Kleppner developed the atomic hydrogen maser, looking to increase the accuracy with which the hyperfine separations of atomic hydrogen, deuterium and tritium could be measured, as well as to investigate how much the hyperfine structure was affected by external magnetic and electric fields. He also participated in developing an extremely stable clock based on a hydrogen maser. From 1967 until 2019, the second has been defined based on 9,192,631,770 hyperfine transition of a cesium-133 atom; the atomic clock which is used to set this standard is an application of Ramsey's work. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1989 "for the invention of the separated oscillatory fields method and its use in the hydrogen maser and other atomic clocks". The Prize was shared with Hans G. Dehmelt and Wolfgang Paul

Wolfgang Paul (; 10 August 1913 – 7 December 1993) was a German physicist, who co-developed the non-magnetic quadrupole mass filter which laid the foundation for what is now called an ion trap. He shared one-half of the Nobel Prize in Ph ...

.

In collaboration with the Institut Laue–Langevin, Ramsey also worked on applying similar methods to beams of neutrons, measuring the neutron magnetic moment and finding a limit to its electric dipole moment

The electric dipole moment is a measure of the separation of positive and negative electrical charges within a system, that is, a measure of the system's overall polarity. The SI unit for electric dipole moment is the coulomb-meter (C⋅m). The ...

. As President of the Universities Research Association

The Universities Research Association is a non-profit association of more than 90 research universities, primarily but not exclusively in the United States. It has members also in Japan, Italy, and in the United Kingdon. It was founded in 1965 a ...

during the 1960s he was involved in the design and construction of the Fermilab in Batavia, Illinois. He also headed a 1982 National Research Council committee that concluded that, contrary to the findings of the House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations, acoustic evidence did not indicate the presence of a second gunman's involvement in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 12:30 p.m. CST in Dallas, Texas, while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza. Kennedy was in the vehicle wi ...

.

Later life

Ramsey eventually became the Eugene Higgins professor of physics at Harvard and retired in 1986. However, he remained active in physics, spending a year as a research fellow at theJoint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics

JILA, formerly known as the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics, is a physical science research institute in the United States. JILA is located on the University of Colorado Boulder campus. JILA was founded in 1962 as a joint institute of ...

(JILA) at the University of Colorado. He also continued visiting professorships at the University of Chicago, Williams College and the University of Michigan. In addition to the Nobel Prize in Physics, Ramsey received a number of awards, including the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award in 1960, Davisson-Germer Prize in 1974, the IEEE Medal of Honor in 1984, the Rabi Prize in 1985, the Rumford Premium Prize in 1985, the Compton Medal in 1986, and the Oersted Medal and the National Medal of Science in 1988. In 1990, Ramsey received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement. He was an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

, and the American Philosophical Society. In 2004, he signed a letter along with 47 other Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make out ...

s endorsing John Kerry for President of the United States as someone who would "restore science to its appropriate place in government".

His first wife, Elinor, died in 1983, after which he married Ellie Welch of Brookline, Massachusetts. Ramsey died on November 4, 2011. He was survived by his wife Ellie, his four daughters from his first marriage, and his stepdaughter and stepson from his second marriage.

Bibliography

*Ramsey, N. F.; Birge, R. W. & U. E. Kruse"Proton–Proton Scattering at 105 MeV and 75 MeV"

Harvard University, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the United States Atomic Energy Commission), (January 31, 1951). *Ramsey, N. F.; Cone, A. A.; Chen, K. W.; Dunning, J. R. Jr.; Hartwig, G.; Walker, J. K. & R. Wilson

"Inelastic Scattering Of Electrons By Protons"

Department of Physics at Harvard University, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the United States Atomic Energy Commission), (December 1966). *Greene, G. L.; Ramsey, N. F.; Mampe, W.; Pendlebury, J. M.; Smith, K. ; Dress, W. B.; Miller, P. D. & P. Perrin

"Determination of the Neutron Magnetic Moment"

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Harvard University, Institut Laue–Langevin, Astronomy Centre of

Sussex University

, mottoeng = Be Still and Know

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £14.4 million (2020)

, budget = £319.6 million (2019–20)

, chancellor = Sanjeev Bhaskar

, vice_chancellor = Sasha Roseneil

, ...

, United States Department of Energy, (June 1981).

*Ramsey, N. F. ''Molecular Beams'', Oxford University Press (First edition 1956, Reprinted 1986).

Notes

References

* * * * * * *External links

Group photograph

taken at ''Lasers'' '93 including (right to left) Norman F. Ramsey, Marlan Scully, and

F. J. Duarte

Francisco Javier "Frank" Duarte (born c. 1954) is a laser physicist and author/editor of several books on tunable lasers.

His research on physical optics and laser development has won several awards, including an Engineering Excellence Award in ...

.Norman Ramsey, an oral history conducted in 1995 by Andrew Goldstein, IEEE History Center, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Papers relating to the Manhattan Project, 1945–1946, collected by Norman Ramsey

Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Libraries, from SIRIS * including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1989 ''Experiments with Separated Oscillatory Fields and Hydrogen Masers'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Ramsey, Norman Foster 1915 births 2011 deaths Columbia College (New York) alumni Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Columbia University faculty Harvard University faculty Nobel laureates in Physics National Medal of Science laureates American Nobel laureates IEEE Medal of Honor recipients Vannevar Bush Award recipients Manhattan Project people Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences American physicists People associated with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki University of Michigan staff Fellows of the American Physical Society Presidents of the American Physical Society Members of the American Philosophical Society