Non-Darwinian Evolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of

The

The

The various alternatives to Darwinian evolution by natural selection were not necessarily mutually exclusive. The evolutionary philosophy of the American palaeontologist

The various alternatives to Darwinian evolution by natural selection were not necessarily mutually exclusive. The evolutionary philosophy of the American palaeontologist

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

and the relatedness

The coefficient of relationship is a measure of the degree of consanguinity (or biological relationship) between two individuals. The term coefficient of relationship was defined by Sewall Wright in 1922, and was derived from his definition of th ...

of different groups of living things. The alternatives in question do not deny that evolutionary changes over time are the origin of the diversity of life, nor that the organisms alive today share a common ancestor from the distant past (or ancestors, in some proposals); rather, they propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change over time, arguing against mutations acted on by natural selection as the most important driver of evolutionary change.

This distinguishes them from certain other kinds of arguments that deny that large-scale evolution of any sort has taken place, as in some forms of creationism

Creationism is the faith, religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of Creation myth, divine creation, and is often Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific.#Gunn 2004, Gun ...

, which do not propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change but instead deny that evolutionary change has taken place at all. Not all forms of creationism deny that evolutionary change takes place; notably, proponents of theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution), alternatively called evolutionary creationism, is a view that God acts and creates through laws of nature. Here, God is taken as the primary cause while natural cau ...

, such as the biologist Asa Gray

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American botany, botanist of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana'' (1876) was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessaril ...

, assert that evolutionary change does occur and is responsible for the history of life on Earth, with the proviso that this process has been influenced by a god or gods in some meaningful sense.

Where the fact of evolutionary change was accepted but the mechanism proposed by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, was denied, explanations of evolution such as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism is the theory that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow inc ...

, orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an Superseded theories in science, obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolution, evolve ...

, vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

, structuralism

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns t ...

and mutationism

Mutationism is one of several alternatives to evolution by natural selection that have existed both before and after the publication of Charles Darwin's 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species''. In the theory, mutation was the source of novelty, cr ...

(called saltationism before 1900) were entertained. Different factors motivated people to propose non-Darwinian

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sele ...

mechanisms of evolution. Natural selection, with its emphasis on death and competition, did not appeal to some naturalists because they felt it immoral, leaving little room for teleology

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

or the concept of progress (orthogenesis) in the development of life. Some who came to accept evolution, but disliked natural selection, raised religious objections. Others felt that evolution was an inherently progressive process that natural selection alone was insufficient to explain. Still others felt that nature, including the development of life, followed orderly patterns that natural selection could not explain.

By the start of the 20th century, evolution was generally accepted by biologists but natural selection was in eclipse. Many alternative theories were proposed, but biologists were quick to discount theories such as orthogenesis, vitalism and Lamarckism which offered no mechanism for evolution. Mutationism did propose a mechanism, but it was not generally accepted. The modern synthesis a generation later claimed to sweep away all the alternatives to Darwinian evolution, though some have been revived as molecular mechanisms for them have been discovered.

Unchanging forms

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

did not embrace either divine creation or evolution, instead arguing in his biology that each species (''eidos'') was immutable, breeding true to its ideal eternal form (not the same as Plato's theory of forms

The Theory of Forms or Theory of Ideas, also known as Platonic idealism or Platonic realism, is a philosophical theory credited to the Classical Greek philosopher Plato.

A major concept in metaphysics, the theory suggests that the physical w ...

). Aristotle's suggestion in ''De Generatione Animalium

The ''Generation of Animals'' (or ''On the Generation of Animals''; Greek: ''Περὶ ζῴων γενέσεως'' (''Peri Zoion Geneseos''); Latin: ''De Generatione Animalium'') is one of the biological works of the Corpus Aristotelicum, the coll ...

'' of a fixed hierarchy in nature - a ''scala naturae'' ("ladder of nature") provided an early explanation of the continuity of living things. Aristotle saw that animals were teleological

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Applet ...

(functionally end-directed), and had parts that were homologous with those of other animals, but he did not connect these ideas into a concept of evolutionary progress.

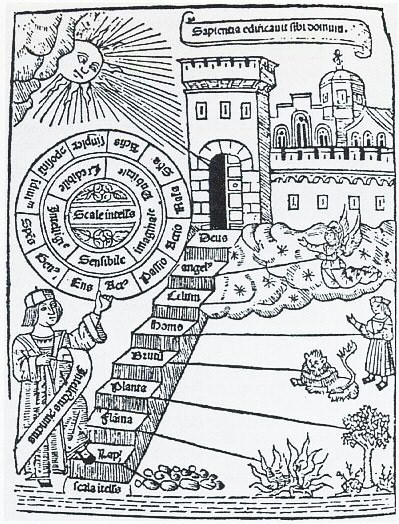

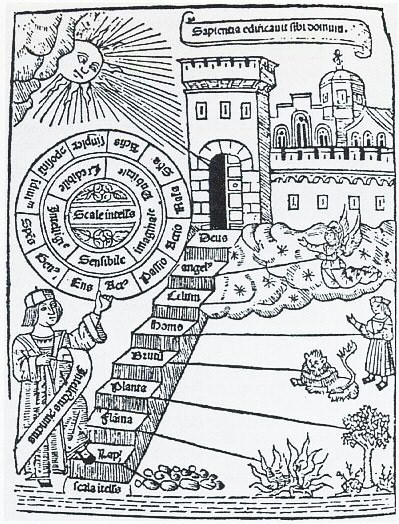

In the Middle Ages, Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

developed Aristotle's view into the idea of a great chain of being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, Human, humans, Animal, animals and Plant, plants to ...

. The image of a ladder inherently suggests the possibility of climbing, but both the ancient Greeks and mediaeval scholastics such as Ramon Lull

Ramon Llull (; ; – 1316), sometimes anglicized as ''Raymond Lully'', was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, Christian apologist and former knight from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art'' ...

maintained that each species remained fixed from the moment of its creation.

By 1818, however, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (; 15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theorie ...

argued in his ''Philosophie anatomique'' that the chain was "a progressive series", where animals like molluscs low on the chain could "rise, by addition of parts, from the simplicity of the first formations to the complication of the creatures at the head of the scale", given sufficient time. Accordingly, Geoffroy and later biologists looked for explanations of such evolutionary change.

Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

's 1812 ''Recherches sur les Ossements Fossiles'' set out his doctrine of the correlation of parts, namely that since an organism was a whole system, all its parts mutually corresponded, contributing to the function of the whole. So, from a single bone the zoologist could often tell what class or even genus the animal belonged to. And if an animal had teeth adapted for cutting meat, the zoologist could be sure without even looking that its sense organs would be those of a predator and its intestines those of a carnivore. A species had an irreducible functional complexity, and "none of its parts can change without the others changing too". Evolutionists expected one part to change at a time, one change to follow another. In Cuvier's view, evolution was impossible, as any one change would unbalance the whole delicate system.

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

's 1856 "Essay on Classification" exemplified German philosophical idealism. This held that each species was complex within itself, had complex relationships to other organisms, and fitted precisely into its environment, as a pine tree in a forest, and could not survive outside those circles. The argument from such ideal forms opposed evolution without offering an actual alternative mechanism. Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

held a similar view in Britain.

The Lamarckian social philosopher and evolutionist Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

, ironically the author of the phrase "survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

" adopted by Darwin, used an argument like Cuvier's to oppose natural selection. In 1893, he stated that a change in any one structure of the body would require all the other parts to adapt to fit in with the new arrangement. From this, he argued that it was unlikely that all the changes could appear at the right moment if each one depended on random variation; whereas in a Lamarckian world, all the parts would naturally adapt at once, through a changed pattern of use and disuse.

Alternative explanations of change

Where the fact of evolutionary change was accepted by biologists butnatural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

was denied, including but not limited to the late 19th century eclipse of Darwinism, alternative scientific explanations such as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an Superseded theories in science, obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolution, evolve ...

, structuralism

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns t ...

, catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism is the theory that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow inc ...

, vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

and theistic evolution were entertained, not necessarily separately. (Purely religious points of view such as young or old earth creationism

Creationism is the faith, religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of Creation myth, divine creation, and is often Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific.#Gunn 2004, Gun ...

or intelligent design

Intelligent design (ID) is a pseudoscientific argument for the existence of God, presented by its proponents as "an evidence-based scientific theory about life's origins".#Numbers 2006, Numbers 2006, p. 373; " Dcaptured headlines for it ...

are not considered here.) Different factors motivated people to propose non-Darwinian evolutionary mechanisms. Natural selection, with its emphasis on death and competition, did not appeal to some naturalists because they felt it immoral, leaving little room for teleology

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

or the concept of progress in the development of life. Some of these scientists and philosophers, like St. George Jackson Mivart and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, who came to accept evolution but disliked natural selection, raised religious objections. Others, such as the biologist and philosopher Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

, the botanist George Henslow (son of Darwin's mentor John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow (6 February 1796 – 16 May 1861) was an English Anglican priest, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to Charles Darwin.

Early life

Henslow was born at Rochester, Kent, the son of a solicit ...

, also a botanist), and the author Samuel Butler, felt that evolution was an inherently progressive process that natural selection alone was insufficient to explain. Still others, including the American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

and Alpheus Hyatt

Alpheus Hyatt (April 5, 1838 – January 15, 1902) was an American zoologist and palaeontologist. Hyatt served as the founding president of the American Society of Naturalists from 1883 to 1884 and was the founding editor of the journal '' T ...

, had an idealist perspective and felt that nature, including the development of life, followed orderly patterns that natural selection could not explain.

Some felt that natural selection would be too slow, given the estimates of the age of the earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion (astrophysics), accretion, or Internal structure of Earth, core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating ...

and sun (10–100 million years) being made at the time by physicists such as Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (26 June 182417 December 1907), was a British mathematician, Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and engineer. Born in Belfast, he was the Professor of Natural Philosophy (Glasgow), professor of Natur ...

, and some felt that natural selection could not work because at the time the models for inheritance involved blending of inherited characteristics, an objection raised by the engineer Fleeming Jenkin

Henry Charles Fleeming Jenkin Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (; 25 March 1833 – 12 June 1885) was a British engineer, inventor, economist, linguist, actor and dramatist known as the inventor of the cable car or Aerial tramway#Telpherage, t ...

in a review of ''Origin'' written shortly after its publication. Another factor at the end of the 19th century was the rise of a new faction of biologists, typified by geneticists like Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries (; 16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware of ...

and Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an Americans, American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, Embryology, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries e ...

, who wanted to recast biology as an experimental laboratory science. They distrusted the work of naturalists like Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

, dependent on field observations of variation, adaptation, and biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the species distribution, distribution of species and ecosystems in geography, geographic space and through evolutionary history of life, geological time. Organisms and biological community (ecology), communities o ...

, as being overly anecdotal. Instead they focused on topics like physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

that could be investigated with controlled experiments in the laboratory, and discounted less accessible phenomena like natural selection and adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

to the environment.

Vitalism

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since Early Modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

times, vitalism stood in contrast to the mechanistic explanation of biological systems started by Descartes. Nineteenth century chemists set out to disprove the claim that forming organic compounds required vitalist influence. In 1828, Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler Royal Society of London, FRS(For) HonFRSE (; 31 July 180023 September 1882) was a German chemist known for his work in both organic chemistry, organic and inorganic chemistry, being the first to isolate the chemical elements be ...

showed that urea

Urea, also called carbamide (because it is a diamide of carbonic acid), is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two Amine, amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest am ...

could be made entirely from inorganic chemicals. Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

believed that fermentation

Fermentation is a type of anaerobic metabolism which harnesses the redox potential of the reactants to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and organic end products. Organic molecules, such as glucose or other sugars, are catabolized and reduce ...

required whole organisms, which he supposed carried out chemical reactions found only in living things. The embryologist Hans Driesch

Hans Adolf Eduard Driesch (28 October 1867 – 17 April 1941) was a German biologist and philosopher from Bad Kreuznach. He is most noted for his early experimental work in embryology and for his neo-vitalist philosophy of entelechy. He has also ...

, experimenting on sea urchin

Sea urchins or urchins () are echinoderms in the class (biology), class Echinoidea. About 950 species live on the seabed, inhabiting all oceans and depth zones from the intertidal zone to deep seas of . They typically have a globular body cove ...

eggs, showed that separating the first two cells led to two complete but small blastula

Blastulation is the stage in early animal embryonic development that produces the blastula. In mammalian development, the blastula develops into the blastocyst with a differentiated inner cell mass and an outer trophectoderm. The blastula (fr ...

s, seemingly showing that cell division did not divide the egg into sub-mechanisms, but created more cells each with the vital capability to form a new organism. Vitalism faded out with the demonstration of more satisfactory mechanistic explanations of each of the functions of a living cell or organism. By 1931, biologists had "almost unanimously abandoned vitalism as an acknowledged belief."

Theistic evolution

The American botanistAsa Gray

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American botany, botanist of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana'' (1876) was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessaril ...

used the name "theistic evolution" for his point of view, presented in his 1876 book ''Essays and Reviews Pertaining to Darwinism''. He argued that the deity supplies beneficial mutations to guide evolution. St George Jackson Mivart argued instead in his 1871 ''On the Genesis of Species'' that the deity, equipped with foreknowledge, sets the direction of evolution by specifying the (orthogenetic) laws that govern it, and leaves species to evolve according to the conditions they experience as time goes by. The Duke of Argyll set out similar views in his 1867 book ''The Reign of Law''. According to the historian Edward Larson, the theory failed as an explanation in the minds of late 19th century biologists as it broke the rules of methodological naturalism

In philosophy, naturalism is the idea that only natural laws and forces (as opposed to supernatural ones) operate in the universe. In its primary sense, it is also known as ontological naturalism, metaphysical naturalism, pure naturalism, phi ...

which they had grown to expect. Accordingly, by around 1900, biologists no longer saw theistic evolution as a valid theory. In Larson's view, by then it "did not even merit a nod among scientists." In the 20th century, theistic evolution could take other forms, such as the orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an Superseded theories in science, obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolution, evolve ...

of Teilhard de Chardin.

Orthogenesis

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (; 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit, Catholic priest, scientist, palaeontologist, theologian, and teacher. He was Darwinian and progressive in outlook and the author of several influential theologica ...

openly spiritual, others such as Theodor Eimer

Gustav Heinrich Theodor Eimer (22 February 1843 – 29 May 1898) was a German zoologist. He was a popularizer of orthogenesis, a form of directed evolution through mutations that made use of Lamarckian principles.

Life and work

Eimer was born ...

's apparently simply biological. These theories often combined orthogenesis with other supposed mechanisms. For example, Eimer believed in Lamarckian evolution, but felt that internal laws of growth determined which characteristics would be acquired and would guide the long-term direction of evolution.

Orthogenesis was popular among paleontologists such as Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was professor of anatomy at Columbia University, president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 y ...

. They believed that the fossil record showed unidirectional change, but did not necessarily accept that the mechanism driving orthogenesis was teleological

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Applet ...

(goal-directed). Osborn argued in his 1918 book ''Origin and Evolution of Life'' that trends in Titanothere horns were both orthogenetic and non- adaptive, and could be detrimental to the organism. For instance, they supposed that the large antlers of the Irish elk had caused its extinction.

Support for orthogenesis fell during the modern synthesis in the 1940s when it became apparent that it could not explain the complex branching patterns of evolution revealed by statistical analysis of the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

. Work in the 21st century has supported the mechanism and existence of mutation-biased adaptation (a form of mutationism), meaning that constrained orthogenesis is now seen as possible. Moreover, the self-organizing

Self-organization, also called spontaneous order in the social sciences, is a process where some form of overall order and disorder, order arises from local interactions between parts of an initially disordered system. The process can be spont ...

processes involved in certain aspects of embryonic development

In developmental biology, animal embryonic development, also known as animal embryogenesis, is the developmental stage of an animal embryo. Embryonic development starts with the fertilization of an egg cell (ovum) by a sperm, sperm cell (spermat ...

often exhibit stereotypical morphological outcomes, suggesting that evolution will proceed in preferred directions once key molecular components are in place.

Lamarckism

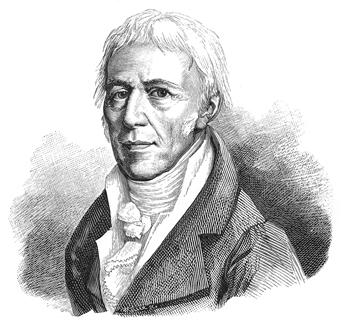

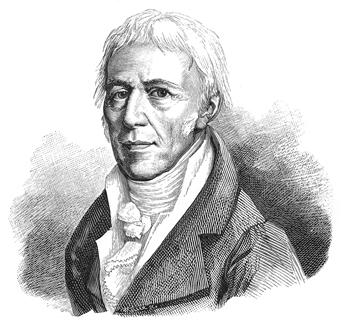

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

's 1809 evolutionary theory, transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

, was based on a progressive (orthogenetic) drive toward greater complexity. Lamarck also shared the belief, common at the time, that characteristics acquired during an organism's life could be inherited by the next generation, producing adaptation to the environment. Such characteristics were caused by the use or disuse of the affected part of the body. This minor component of Lamarck's theory became known, much later, as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

. Darwin included ''Effects of the increased Use and Disuse of Parts, as controlled by Natural Selection'' in ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', giving examples such as large ground feeding birds getting stronger legs through exercise, and weaker wings from not flying until, like the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

, they could not fly at all. In the late 19th century, neo-Lamarckism was supported by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

, the American paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

s Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

and Alpheus Hyatt

Alpheus Hyatt (April 5, 1838 – January 15, 1902) was an American zoologist and palaeontologist. Hyatt served as the founding president of the American Society of Naturalists from 1883 to 1884 and was the founding editor of the journal '' T ...

, and the American entomologist

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

Alpheus Packard. Butler and Cope believed that this allowed organisms to effectively drive their own evolution. Packard argued that the loss of vision in the blind cave insects he studied was best explained through a Lamarckian process of atrophy through disuse combined with inheritance of acquired characteristics. Meanwhile, the English botanist George Henslow studied how environmental stress affected the development of plants, and he wrote that the variations induced by such environmental factors could largely explain evolution; he did not see the need to demonstrate that such variations could actually be inherited. Critics pointed out that there was no solid evidence for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Instead, the experimental work of the German biologist August Weismann

August Friedrich Leopold Weismann (; 17 January 18345 November 1914) was a German evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist. Fellow German Ernst Mayr ranked him as the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Charl ...

resulted in the germ plasm theory of inheritance, which Weismann said made the inheritance of acquired characteristics impossible, since the Weismann barrier

The Weismann barrier, proposed by August Weismann, is the strict distinction between the "immortal" germ cell lineages producing gametes and "disposable" somatic cells in animals (but not plants), in contrast to Charles Darwin's proposed pangenesi ...

would prevent any changes that occurred to the body after birth from being inherited by the next generation.

In modern epigenetics

In biology, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix ''epi-'' (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "on top of" or "in ...

, biologists observe that phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

s depend on heritable changes to gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

that do not involve changes to the DNA sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nu ...

. These changes can cross generations in plants, animals, and prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s. This is not identical to traditional Lamarckism, as the changes do not last indefinitely and do not affect the germ line and hence the evolution of genes.

Catastrophism

Catastrophism is thehypothesis

A hypothesis (: hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. A scientific hypothesis must be based on observations and make a testable and reproducible prediction about reality, in a process beginning with an educated guess o ...

, argued by the French anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

and paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

in his 1812 ''Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes'', that the various extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

s and the patterns of faunal succession seen in the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

record were caused by large-scale natural catastrophes such as volcanic eruptions and, for the most recent extinctions in Eurasia, the inundation of low-lying areas by the sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

. This was explained purely by natural events: he did not mention Noah's flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is a Hebrew flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microcosm of Noah's ark.

The B ...

, nor did he ever refer to divine creation as the mechanism for repopulation after an extinction event, though he did not support evolutionary theories such as those of his contemporaries Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire either. Cuvier believed that the stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

record indicated that there had been several such catastrophes, recurring natural events, separated by long periods of stability during the history of life on earth. This led him to believe the Earth was several million years old.

Catastrophism has found a place in modern biology with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

period, as proposed in a paper by

Walter

Walter may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Walter (name), including a list of people and fictional and mythical characters with the given name or surname

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–19 ...

and Luis Alvarez in 1980. It argued that a asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet—an object larger than a meteoroid that is neither a planet nor an identified comet—that orbits within the Solar System#Inner Solar System, inner Solar System or is co-orbital with Jupiter (Trojan asteroids). As ...

struck Earth 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

period. The event, whatever it was, made about 70% of all species extinct, including the dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s, leaving behind the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary, formerly known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) boundary, is a geological signature, usually a thin band of rock containing much more iridium than other bands. The K–Pg boundary marks the end o ...

. In 1990, a candidate crater marking the impact was identified at Chicxulub

The Chicxulub crater is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore, but the crater is named after the onshore community of Chicxulub Pueblo (not the larger coastal town of Chicxulub Puerto). I ...

in the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula ( , ; ) is a large peninsula in southeast Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west of the peninsula from the C ...

of Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

.

Structuralism

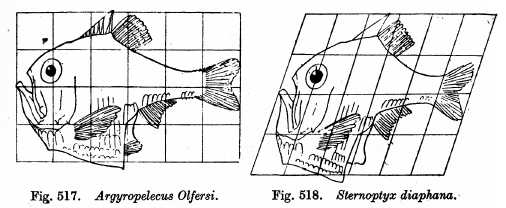

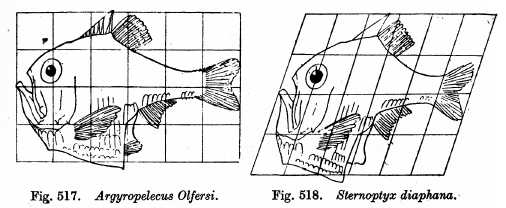

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

s. Before Darwin, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (; 15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theorie ...

argued that animals shared homologous parts, and that if one was enlarged, the others would be reduced in compensation. After Darwin, D'Arcy Thompson

Sir D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson CB FRS FRSE (2 May 1860 – 21 June 1948) was a Scottish biologist, mathematician and classics scholar. He was a pioneer of mathematical and theoretical biology, travelled on expeditions to the Bering Strait ...

hinted at vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

and offered geometric explanations in his classic 1917 book ''On Growth and Form

''On Growth and Form'' is a book by the Scottish mathematical biology, mathematical biologist D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860–1948). The book is long – 793 pages in the first edition of 1917, 1116 pages in the second edition of 1942.

The ...

''. Adolf Seilacher suggested mechanical inflation for "pneu" structures in Ediacaran biota

The Ediacaran (; formerly Vendian) biota is a taxonomic period classification that consists of all life forms that were present on Earth during the Ediacaran Period (). These were enigmatic tubular and frond-shaped, mostly sessile, organis ...

fossils such as ''Dickinsonia

''Dickinsonia'' is a genus of extinct organism that lived during the late Ediacaran period in what is now Australia, China, Russia, and Ukraine. It had a round, bilaterally symmetric body with multiple segments running along it. It could range f ...

''. Günter P. Wagner argued for developmental bias, structural constraints on embryonic development

In developmental biology, animal embryonic development, also known as animal embryogenesis, is the developmental stage of an animal embryo. Embryonic development starts with the fertilization of an egg cell (ovum) by a sperm, sperm cell (spermat ...

. Wagner, Günter P., ''Homology, Genes, and Evolutionary Innovation''. Princeton University Press. 2014. Chapter 1: The Intellectual Challenge of Morphological Evolution: A Case for Variational Structuralism. Pages 7–38 Stuart Kauffman

Stuart Alan Kauffman (born September 28, 1939) is an American medical doctor, theoretical biology, theoretical biologist, and complex systems researcher who studies the origin of life on Earth. He was a professor at the University of Chicago, Un ...

favoured self-organisation

Self-organization, also called spontaneous order in the social sciences, is a process where some form of overall order and disorder, order arises from local interactions between parts of an initially disordered system. The process can be spont ...

, the idea that complex structure emerges holistically and spontaneously from the dynamic interaction of all parts of an organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

. Michael Denton argued for laws of form by which Platonic universals or "Types" are self-organised. In 1979 Stephen J. Gould and Richard Lewontin

Richard Charles Lewontin (March 29, 1929 – July 4, 2021) was an American evolutionary biologist, mathematician, geneticist, and social commentator. A leader in developing the mathematical basis of population genetics and evolutionary theory, ...

proposed biological "spandrels", features created as a byproduct of the adaptation of nearby structures. Gerd Müller

Gerhard "Gerd" Müller (; 3 November 1945 – 15 August 2021) was a German professional association football, footballer. A prolific Forward (association football)#Striker, striker, especially in and around the six-yard box, he is widely regarde ...

and Stuart Newman argued that the appearance in the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

of most of the current phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

in the Cambrian explosion was "pre- Mendelian" evolution caused by plastic responses of morphogenetic systems that were partly organized by physical mechanisms. Brian Goodwin, described by Wagner as part of "a fringe

Fringe may refer to:

Arts and music

* "The Fringe", or Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the world's largest arts festival

* Adelaide Fringe, the world's second-largest annual arts festival

* Fringe theatre, a name for alternative theatre

* Purple fri ...

movement in evolutionary biology", denied that biological complexity can be reduced to natural selection, and argued that pattern formation

The science of pattern formation deals with the visible, (statistically) orderly outcomes of self-organization and the common principles behind similar patterns in nature.

In developmental biology, pattern formation refers to the generation of c ...

is driven by morphogenetic field

In the developmental biology of the early twentieth century, a morphogenetic field is a research hypothesis and a discrete region of cells in an embryo.

The term ''morphogenetic field'' conceptualizes the scientific experimental finding that ...

s. Darwinian biologists have criticised structuralism, emphasising that there is plentiful evidence from deep homology

In evolutionary developmental biology, the concept of deep homology is used to describe cases where growth and differentiation processes are governed by genetic mechanisms that are homologous and deeply conserved across a wide range of specie ...

that gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s have been involved in shaping organisms throughout evolutionary history

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and extinct organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to the present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for '' gigaannum'') and ...

. They accept that some structures such as the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

self-assemble, but question the ability of self-organisation to drive large-scale evolution.

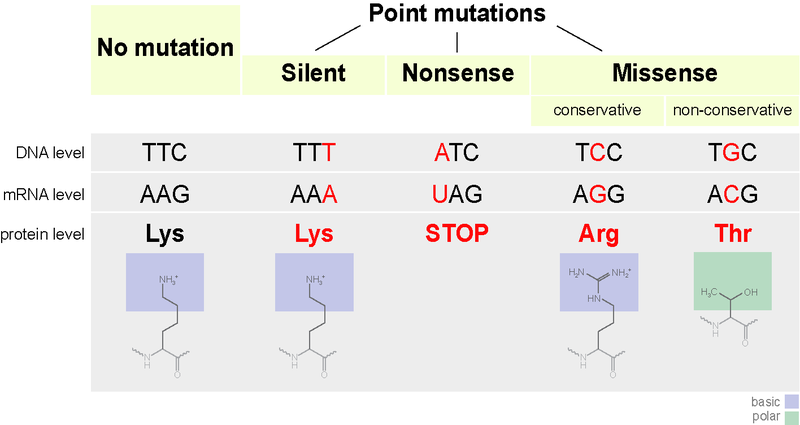

Saltationism, mutationism

Saltationism

In biology, saltation () is a sudden and large mutational change from one generation to the next, potentially causing single-step speciation. This was historically offered as an alternative to Darwinism. Some forms of mutationism were effectivel ...

held that new species arise as a result of large mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s. It was seen as a much faster alternative to the Darwinian concept of a gradual process of small random variations being acted on by natural selection. It was popular with early geneticists such as Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries (; 16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware of ...

, who along with Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

helped rediscover Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel Order of Saint Augustine, OSA (; ; ; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thom ...

's laws of inheritance in 1900, William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscover ...

, a British zoologist who switched to genetics, and early in his career, Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an Americans, American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, Embryology, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries e ...

. These ideas developed into mutationism

Mutationism is one of several alternatives to evolution by natural selection that have existed both before and after the publication of Charles Darwin's 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species''. In the theory, mutation was the source of novelty, cr ...

, the mutation theory of evolution. This held that species went through periods of rapid mutation, possibly as a result of environmental stress, that could produce multiple mutations, and in some cases completely new species, in a single generation, based on de Vries's experiments with the evening primrose, '' Oenothera'', from 1886. The primroses seemed to be constantly producing new varieties with striking variations in form and color, some of which appeared to be new species because plants of the new generation could only be crossed with one another, not with their parents. However, Hermann Joseph Muller

Hermann Joseph Muller (December 21, 1890 – April 5, 1967) was an American geneticist who was awarded the 1946 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, "for the discovery that mutations can be induced by X-rays". Muller warned of long-term dang ...

showed in 1918 that the new varieties de Vries had observed were the result of polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the biological cell, cells of an organism have more than two paired sets of (Homologous chromosome, homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have Cell nucleus, nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning ...

hybrids rather than rapid genetic mutation.

Initially, de Vries and Morgan believed that mutations were so large as to create new forms such as subspecies or even species instantly. Morgan's 1910 fruit fly experiments, in which he isolated mutations for characteristics such as white eyes, changed his mind. He saw that mutations represented small Mendelian characteristics that would only spread through a population when they were beneficial, helped by natural selection. This represented the germ of the modern synthesis, and the beginning of the end for mutationism as an evolutionary force.

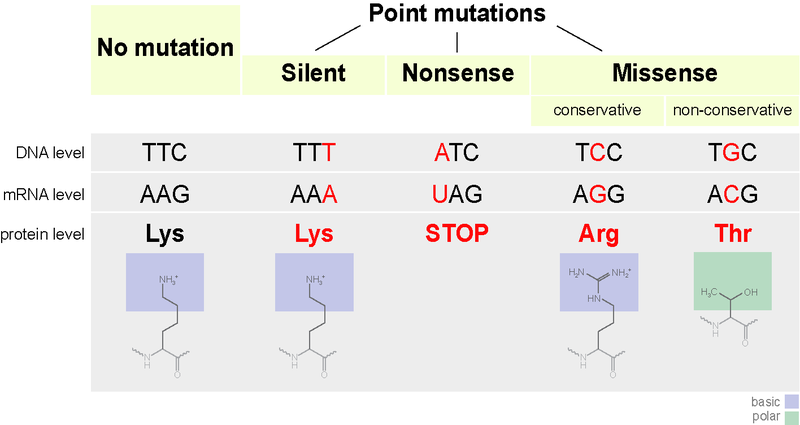

Contemporary biologists accept that mutation and selection both play roles in evolution; the mainstream view is that while mutation supplies material for selection in the form of variation, all non-random outcomes are caused by natural selection. Masatoshi Nei

was a Japanese-born American evolutionary biologist.

Professional life

Masatoshi Nei was born in 1931 in Miyazaki Prefecture, on Kyūshū Island, Japan.

He received a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Miyazaki in 1953, a ...

argues instead that the production of more efficient genotypes by mutation is fundamental for evolution, and that evolution is often mutation-limited. The endosymbiotic theory

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possibl ...

implies rare but major events of saltational evolution by symbiogenesis

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possibl ...

. Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese ( ; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal ...

and colleagues suggested that the absence of RNA signature continuum between domains of bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

, and eukarya

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of l ...

shows that these major lineages materialized via large saltations in cellular organization. Saltation at a variety of scales is agreed to be possible by mechanisms including polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the biological cell, cells of an organism have more than two paired sets of (Homologous chromosome, homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have Cell nucleus, nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning ...

y, which certainly can create new species of plant, gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene ...

, lateral gene transfer, and transposable element

A transposable element (TE), also transposon, or jumping gene, is a type of mobile genetic element, a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome.

The discovery of mobile genetic elements earned Barbara McClinto ...

s (jumping genes).

Genetic drift

The

The neutral theory of molecular evolution

The neutral theory of molecular evolution holds that most evolutionary changes occur at the molecular level, and most of the variation within and between species are due to random genetic drift of mutant alleles that are selectively neutral. The ...

, proposed by Motoo Kimura

(November 13, 1924 – November 13, 1994) was a Japanese biologist best known for introducing the neutral theory of molecular evolution in 1968. He became one of the most influential theoretical population geneticists. He is remembered in ge ...

in 1968, holds that at the molecular level most evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

ary changes and most of the variation within and between species is not caused by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

but by genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as random genetic drift, allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the Allele frequency, frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene va ...

of mutant

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It i ...

allele

An allele is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or Locus (genetics), locus, on a DNA molecule.

Alleles can differ at a single position through Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), ...

s that are neutral. A neutral mutation

Neutral mutations are changes in DNA sequence that are neither beneficial nor detrimental to the ability of an organism to survive and reproduce. In population genetics, mutations in which natural selection does not affect the spread of the mutatio ...

is one that does not affect an organism's ability to survive and reproduce. The neutral theory allows for the possibility that most mutations are deleterious, but holds that because these are rapidly purged by natural selection, they do not make significant contributions to variation within and between species at the molecular level. Mutations that are not deleterious are assumed to be mostly neutral rather than beneficial.

The theory was controversial as it sounded like a challenge to Darwinian evolution; controversy was intensified by a 1969 paper by Jack Lester King and Thomas H. Jukes, provocatively but misleadingly titled " Non-Darwinian Evolution". It provided a wide variety of evidence including protein sequence

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein. By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosynthe ...

comparisons, studies of the Treffers mutator gene in ''E. coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia'' that is commonly foun ...

'', analysis of the genetic code, and comparative immunology

Immunology is a branch of biology and medicine that covers the study of Immune system, immune systems in all Organism, organisms.

Immunology charts, measures, and contextualizes the Physiology, physiological functioning of the immune system in ...

, to argue that most protein evolution is due to neutral mutations and genetic drift.

According to Kimura, the theory applies only for evolution at the molecular level, while phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

evolution is controlled by natural selection, so the neutral theory does not constitute a true alternative.

Combined theories

Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

is a case in point. Cope, a religious man, began his career denying the possibility of evolution. In the 1860s, he accepted that evolution could occur, but, influenced by Agassiz, rejected natural selection. Cope accepted instead the theory of recapitulation of evolutionary history during the growth of the embryo - that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the ovum, egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to t ...

, which Agassiz believed showed a divine plan leading straight up to man, in a pattern revealed both in embryology

Embryology (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, ''-logy, -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the Prenatal development (biology), prenatal development of gametes (sex ...

and palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

. Cope did not go so far, seeing that evolution created a branching tree of forms, as Darwin had suggested. Each evolutionary step was however non-random: the direction was determined in advance and had a regular pattern (orthogenesis), and steps were not adaptive but part of a divine plan (theistic evolution). This left unanswered the question of why each step should occur, and Cope switched his theory to accommodate functional adaptation for each change. Still rejecting natural selection as the cause of adaptation, Cope turned to Lamarckism to provide the force guiding evolution. Finally, Cope supposed that Lamarckian use and disuse operated by causing a vitalist growth-force substance, "bathmism", to be concentrated in the areas of the body being most intensively used; in turn, it made these areas develop at the expense of the rest. Cope's complex set of beliefs thus assembled five evolutionary philosophies: recapitulationism, orthogenesis, theistic evolution, Lamarckism, and vitalism. Other palaeontologists and field naturalists continued to hold beliefs combining orthogenesis and Lamarckism until the modern synthesis in the 1930s.

Rebirth of natural selection, with continuing alternatives

By the start of the 20th century, during the eclipse of Darwinism, biologists were doubtful of natural selection, but equally were quick to discount theories such as orthogenesis, vitalism and Lamarckism which offered no mechanism for evolution. Mutationism did propose a mechanism, but it was not generally accepted. The modern synthesis a generation later, roughly between 1918 and 1932, broadly swept away all the alternatives to Darwinism, though some including forms of orthogenesis,epigenetic mechanisms

In biology, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix ''epi-'' (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "on top of" or "in ...

that resemble Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, catastrophism, structuralism, and mutationism have been revived, such as through the discovery of molecular mechanisms.

Biology has become Darwinian, but belief in some form of progress (orthogenesis) remains both in the public mind and among biologists. Ruse argues that evolutionary biologists will probably continue to believe in progress for three reasons. Firstly, the anthropic principle

In cosmology, the anthropic principle, also known as the observation selection effect, is the proposition that the range of possible observations that could be made about the universe is limited by the fact that observations are only possible in ...

demands people able to ask about the process that led to their own existence, as if they were the pinnacle of such progress. Secondly, scientists in general and evolutionists in particular believe that their work is leading them progressively closer to a true grasp of reality, as knowledge increases, and hence (runs the argument) there is progress in nature also. Ruse notes in this regard that Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, zoologist, science communicator and author. He is an Oxford fellow, emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford, and was Simonyi Professor for the Publ ...

explicitly compares cultural progress with meme

A meme (; ) is an idea, behavior, or style that Mimesis, spreads by means of imitation from person to person within a culture and often carries symbolic meaning representing a particular phenomenon or theme. A meme acts as a unit for carrying c ...

s to biological progress with genes. Thirdly, evolutionists are self-selected; they are people, such as the entomologist and sociobiologist E. O. Wilson

Edward Osborne Wilson (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an American biologist, naturalist, ecologist, and entomologist known for developing the field of sociobiology.

Born in Alabama, Wilson found an early interest in nature and frequ ...

, who are interested in progress to supply a meaning for life.

See also

*Coloration evidence for natural selection

Animal coloration provided important early Evidence of common descent, evidence for evolution by natural selection, at a time when little direct evidence was available. Three major functions of coloration were discovered in the second half of ...

* History of evolutionary thought

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity. With the beginnings of modern Taxonomy (biology), biological taxonomy in the late 17th cent ...

* Objections to evolution

Objections to evolution have been raised since evolutionary ideas came to prominence in the 19th century. When Charles Darwin published his 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species'', his theory of evolution (the idea that species arose through desc ...

* Extended evolutionary synthesis

The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) consists of a set of theoretical concepts argued to be more comprehensive than the earlier modern synthesis of evolutionary biology that took place between 1918 and 1942. The extended evolutionary synthe ...

* Lysenkoism

Lysenkoism ( ; ) was a political campaign led by the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko against genetics and science-based agriculture in the mid-20th century, rejecting natural selection in favour of a form of Lamarckism, as well as expanding upon ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Evolution Evolutionary biology History of evolutionary biology Non-Darwinian evolution