Noble Savages on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In Western

The first century

The first century  By the 18th century, Montaigne's predecessor to the noble savage, ''nature's gentleman'' was a stock character usual to the sentimental literature of the time, for which a type of non-European Other became a background character for European stories about adventurous Europeans in the strange lands beyond continental Europe. For the novels, the opera, and the stageplays, the stock of characters included the "Virtuous Milkmaid" and the "Servant-More-Clever-Than-the-Master" (e.g.

By the 18th century, Montaigne's predecessor to the noble savage, ''nature's gentleman'' was a stock character usual to the sentimental literature of the time, for which a type of non-European Other became a background character for European stories about adventurous Europeans in the strange lands beyond continental Europe. For the novels, the opera, and the stageplays, the stock of characters included the "Virtuous Milkmaid" and the "Servant-More-Clever-Than-the-Master" (e.g.

The themes about the person and ''

The themes about the person and ''

Despite European idealization of the mythical noble savage as a type of morally superior man, in the essay “The Noble Savage” (1853), Dickens expressed repugnance for the American Indians and their way of life, because they were dirty and cruel and continually quarrelled among themselves. In the satire of romanticised primitivism Dickens showed that the painter Catlin, the Indian Gallery of portraits and landscapes, and the white people who admire the idealized American Indians or the

Despite European idealization of the mythical noble savage as a type of morally superior man, in the essay “The Noble Savage” (1853), Dickens expressed repugnance for the American Indians and their way of life, because they were dirty and cruel and continually quarrelled among themselves. In the satire of romanticised primitivism Dickens showed that the painter Catlin, the Indian Gallery of portraits and landscapes, and the white people who admire the idealized American Indians or the

''The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth''

(Reprint) New York: Cosimo Press, 2008. * Edgerton, Robert (1992). ''Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony.'' New York: Free Press. * Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. (2008

"'He Scarcely Resembles the Real Man': images of the Indian in popular culture".

Website

''Our Legacy''

Material relating to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, found in Saskatchewan cultural and heritage collections. * Ellingson, Ter. (2001). ''The Myth of the Noble Savage'' (Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press). * Fabian, Johannes. ''Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object'' * Fairchild, Hoxie Neale (1928). ''The Noble Savage: A Study in Romantic Naturalism'' (New York) * Fitzgerald, Margaret Mary (

"British and Indian Identities in a Picture by Benjamin West"

''Eighteenth-Century Studies'' 31: 3 (Spring 1998): 283–305 * Rollins, Peter C. and John E. O'Connor, editors (1998). ''Hollywood's Indian : the Portrayal of the Native American in Film.'' Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press. * Tinker, Chaunchy Brewster (1922). ''Nature's Simple Plan: a phase of radical thought in the mid-eighteenth century''. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. * Torgovnick, Marianna (1991). ''Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives'' (Chicago) * Whitney, Lois Payne (1934). ''Primitivism and the Idea of Progress in English Popular Literature of the Eighteenth Century''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press * Wolf, Eric R.(1982). ''Europe and the People without History''. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Massacres during the Wars of Religion: The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre: a foundational event

Louis Menand. "What Comes Naturally". A review of Steven Pinker's ''The Blank Slate'' from ''The New Yorker''

Peter Gay. "Breeding is Fundamental". ''Book Forum''. April / May 2009

{{authority control Stock characters Multiculturalism Anthropology Cultural concepts Anti-indigenous racism Ethnic and racial stereotypes

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, and literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, the Myth of the Noble savage refers to a stock character

A stock character, also known as a character archetype, is a type of character in a narrative (e.g. a novel, play, television show, or film) whom audiences recognize across many narratives or as part of a storytelling tradition or convention. Th ...

who is uncorrupted by civilization. As such, the "noble" savage symbolizes the innate goodness and moral superiority of a primitive people living in harmony with nature. In the heroic drama

Heroic drama is a type of Play (theatre), play popular during the English Restoration, Restoration era in England, distinguished by both its verse structure and its subject matter. The subgenre of heroic drama evolved through several works of the ...

of the stageplay '' The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards'' (1672), John Dryden

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration (En ...

represents the ''noble savage'' as an archetype of Man-as-Creature-of-Nature.

The intellectual politics of the Stuart Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

(1660–1688) expanded Dryden's playwright usage of ''savage'' to denote a human ''wild beast'' and a ''wild man''. Concerning civility and incivility, in the ''Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit'' (1699), the philosopher Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (26 February 1671 – 16 February 1713) was an English peer, Whig politician, philosopher and writer.

Early life

He was born at Exeter House in London, the son and first child of the future An ...

, said that men and women possess an innate morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

, a sense of right and wrong conduct, which is based upon the intellect

Intellect is a faculty of the human mind that enables reasoning, abstraction, conceptualization, and judgment. It enables the discernment of truth and falsehood, as well as higher-order thinking beyond immediate perception. Intellect is dis ...

and the emotions, and not based upon religious doctrine.

In 18th-century anthropology, the term ''noble savage'' then denoted ''nature's gentleman'', an ideal man born from the sentimentalism of moral sense theory

Moral sense theory (also known as moral sentimentalism) is a theory in moral epistemology and meta-ethics concerning the discovery of moral truths. Moral sense theory typically holds that distinctions between morality and immorality are discovered ...

. In the 19th century, in the essay "The Noble Savage" (1853) Charles Dickens rendered the noble savage into a rhetorical oxymoron

An oxymoron (plurals: oxymorons and oxymora) is a figure of speech that Juxtaposition, juxtaposes concepts with opposite meanings within a word or in a phrase that is a self-contradiction (disambiguation), self-contradiction. As a rhetorical de ...

by satirizing the British romanticisation of Primitivism

In the arts of the Western world, Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that means to recreate the experience of ''the primitive'' time, place, and person, either by emulation or by re-creation. In Western philosophy, Primitivism propo ...

in philosophy and in the arts made possible by moral sentimentalism.

In many ways, the myth of the noble savage entails fantasies about the non-West that cut to the core of the conversation in the social sciences about Orientalism, colonialism and exoticism. The key question that emerges here is whether an admiration of "the Other" as noble undermines or reproduces the dominant hierarchy, whereby the Other is subjugated by Western powers.

Origins

The first century

The first century Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

work ''De origine et situ Germanorum

The ''Germania'', written by the Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus around 98 AD and originally titled ''On the Origin and Situation of the Germans'' (), is a historical and ethnographic work on the Germanic peoples outside the Roman ...

'' (''On the Origin and Situation of the Germans'') by Publius Cornelius Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical ...

introduced the idea of the ''noble savage'' to the Western World

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

in 98 AD, describing the ancient Germanic people as aligned with ancient Roman virtues

Ancient history is a time period from the History of writing, beginning of writing and recorded human history through late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the development of Sumerian language, ...

, such as bravery and honesty.

The 12th-century Andalusian allegorical novel ''Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

''Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān'' (; also known as Hai Eb'n Yockdan) is an Arabic philosophical novel and an allegorical tale written by Ibn Tufail ( – 1185) in the early 12th century in al-Andalus. Names by which the book is also known include the ( ...

'' developed the idea through its ''noble savage'' titular protagonist understanding natural theology

Natural theology is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics, such as the existence of a deity, based on human reason. It is distinguished from revealed theology, which is based on supernatural sources such as ...

in a ''tabula rasa

''Tabula rasa'' (; Latin for "blank slate") is the idea of individuals being born empty of any built-in mental content, so that all knowledge comes from later perceptions or sensory experiences. Proponents typically form the extreme "nurture" ...

'' existence without any education or contact with the outside world, inspiring later Western philosophy and literature during Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

.

The stock character

A stock character, also known as a character archetype, is a type of character in a narrative (e.g. a novel, play, television show, or film) whom audiences recognize across many narratives or as part of a storytelling tradition or convention. Th ...

of the ''noble savage'' appears in the essay "Of Cannibals

''Of Cannibals'' (''Des Cannibales''), written circa 1580, is an essay, one of those in the collection ''Essays'', by Michel de Montaigne, describing the ceremonies of the Tupinambá people in Brazil. In particular, he reported about how the group ...

" (1580), about the Tupinambá people

The Tupinambá ( Tupinambás) are one of the various Tupi ethnic groups that inhabit present-day Brazil, and who had been living there long before the conquest of the region by Portuguese colonial settlers. The name Tupinambá was also applied t ...

of Brazil, wherein the philosopher Michel de Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne ( ; ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), commonly known as Michel de Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularising the the essay ...

presents "Nature's Gentleman", the ''bon sauvage'' counterpart to civilized Europeans in the 16th century.

;

The first usage of the term ''noble savage'' in English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian languages, Anglo-Frisian d ...

occurs in John Dryden's stageplay '' The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards'' (1672), about the troubled love of the hero Almanzor and the Moorish beauty Almahide, in which the protagonist defends his life as a free man by denying a prince's right to put him to death, because he is not a subject of the prince:

By the 18th century, Montaigne's predecessor to the noble savage, ''nature's gentleman'' was a stock character usual to the sentimental literature of the time, for which a type of non-European Other became a background character for European stories about adventurous Europeans in the strange lands beyond continental Europe. For the novels, the opera, and the stageplays, the stock of characters included the "Virtuous Milkmaid" and the "Servant-More-Clever-Than-the-Master" (e.g.

By the 18th century, Montaigne's predecessor to the noble savage, ''nature's gentleman'' was a stock character usual to the sentimental literature of the time, for which a type of non-European Other became a background character for European stories about adventurous Europeans in the strange lands beyond continental Europe. For the novels, the opera, and the stageplays, the stock of characters included the "Virtuous Milkmaid" and the "Servant-More-Clever-Than-the-Master" (e.g. Sancho Panza

Sancho Panza (; ) is a fictional character in the novel ''Don Quixote'' written by Spain, Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra in 1605. Sancho acts as squire to Don Quixote and provides comments throughout the novel, ...

and Figaro), literary characters who personify the moral superiority of working-class people in the fictional world of the story.

In English literature, British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

was the geographic ''locus classicus'' for adventure and exploration stories about European encounters with the noble savage natives, such as the historical novel '' The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757'' (1826), by James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonial and indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

, and the epic poem ''The Song of Hiawatha

''The Song of Hiawatha'' is an 1855 epic poem in trochaic tetrameter by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow which features Native American characters. The epic relates the fictional adventures of an Ojibwe warrior named Hiawatha and the tragedy of his lo ...

'' (1855), by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to comp ...

, both literary works presented the primitivism

In the arts of the Western world, Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that means to recreate the experience of ''the primitive'' time, place, and person, either by emulation or by re-creation. In Western philosophy, Primitivism propo ...

(geographic, cultural, political) of North America as an ideal place for the European man to commune with Nature, far from the artifice of civilisation; yet in the poem “An Essay on Man

"An Essay on Man" is a poem published by Alexander Pope in 1733–1734. It was dedicated to Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke (pronounced 'Bull-en-brook'), hence the opening line: "Awake, my St John...". It is an effort to rationalize or ...

” (1734), the Englishman Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

portrays the American Indian thus:

To the English intellectual Pope, the American Indian was an abstract being

Existence is the state of having being or reality in contrast to nonexistence and nonbeing. Existence is often contrasted with essence: the essence of an entity is its essential features or qualities, which can be understood even if one do ...

unlike his insular European self; thus, from the Western perspective of "An Essay on Man", Pope's metaphoric usage of ''poor'' means "uneducated and a heathen", but also denotes a savage who is happy with his rustic life in harmony with Nature, and who believes in deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, a form of natural religion

Natural religion most frequently means the "religion of nature", in which God, the soul, spirits, and all objects of the supernatural are considered as part of nature and not separate from it. Conversely, it is also used in philosophy to describe ...

— the idealization and devaluation

Psychoanalytic theory posits that an individual unable to integrate difficult feelings mobilizes specific defenses to overcome these feelings, which the individual perceives to be unbearable. The defense that effects (brings about) this process i ...

of the non-European Other derived from the mirror logic of the Enlightenment belief that "men, everywhere and in all times, are the same".

;

Like Dryden's ''noble savage'' term, Pope's phrase "Lo, the Poor Indian!" was used to dehumanize the natives of North America for European purposes, and so justified white settlers' conflicts with the local Indians for possession of the land. In the mid-19th century, the journalist-editor Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

published the essay "Lo! The Poor Indian!" (1859), about the social condition of the American Indian in the modern United States:

Moreover, during the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonization of the Americas, European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States o ...

(1609–1924) for possession of the land, European white settlers considered the Indians "an inferior breed of men" and mocked them by using the terms "Lo" and "Mr. Lo" as disrespectful forms of address. In the Western U.S., those terms of address also referred to East Coast humanitarians whose conception of the mythical noble-savage American Indian was unlike the warrior who confronted and fought the frontiersman. Concerning the story of the settler Thomas Alderdice, whose wife was captured and killed by Cheyenne Indians

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. The Cheyenne comprise two Native American tribes, the Só'taeo'o or Só'taétaneo'o (more commonly spelled as Suhtai or Sutaio) and the (also spelled Tsitsistas, The term for th ...

, ''The Leavenworth, Kansas, Times and Conservative'' newspaper said: "We wish some philanthropists, who talk about civilizing the Indians, could have heard this unfortunate and almost broken-hearted man tell his story. We think hat the philanthropistswould at least have wavered a little in their ighopinion of the Lo family."

Cultural stereotype

The Roman Empire

In Western literature, the Roman book ''De origine et situ Germanorum

The ''Germania'', written by the Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus around 98 AD and originally titled ''On the Origin and Situation of the Germans'' (), is a historical and ethnographic work on the Germanic peoples outside the Roman ...

'' (''On the Origin and Situation of the Germans'', 98 CE), by the historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical ...

, introduced the anthropologic concept of the ''noble savage'' to the Western World; later a cultural stereotype

An ethnic stereotype or racial stereotype involves part of a system of beliefs about typical characteristics of members of a given ethnic group, their social status , status, societal and cultural norms. A national stereotype does the same for ...

who featured in the exotic-place tourism reported in the European travel literature

The genre of travel literature or travelogue encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

History

Early examples of travel literature include the '' Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' (generally considered a ...

of the 17th and the 18th centuries.

Al-Andalus

The 12th-century Andalusian novel '' The Living Son of the Vigilant'' (''Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān'', 1160), by the polymathIbn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufayl ( – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theologian, physician, astronomer, and vizier.

As a philosopher and novelist, he is most famous for writing the first philosophical nov ...

, explores the subject of natural theology

Natural theology is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics, such as the existence of a deity, based on human reason. It is distinguished from revealed theology, which is based on supernatural sources such as ...

as a means to understand the material world. The protagonist is a ''wild man'' isolated from his society, whose trials and tribulations lead him to knowledge of Allah by living a rustic life in harmony with Mother Nature. Attar, Samar, ''The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl's Influence on Modern Western Thought'' (1989), Lexington Books, .

Kingdom of Spain

In the 15th century, soon after arriving to the Americas in 1492, the Europeans employed the term ''savage'' to dehumanise the ''indigènes'' (noble-savage natives) of the newly discovered "New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

" as ideological justification for the European colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale colonization of the Americas, involving a number of European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century and the early 19th century. The Norse explored and colonized areas of Europe a ...

, called the Age of Discovery (1492–1800); thus with the dehumanizing

upright=1.2, link=Warsaw Ghetto boy, In his report on the suppression of the Nazi camps as "bandits".

file:Abu Ghraib 68.jpg, Lynndie England pulling a leash attached to the neck of a prisoner in Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse, Abu Ghr ...

stereotypes of the ''noble savage'' and the ''indigène'', the ''savage'' and the ''wild man'' the Europeans granted themselves the right to colonize the natives inhabiting the islands and the continental lands of the northern, the central, and the southern Americas.

The conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (; ; ) were Spanish Empire, Spanish and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonizers who explored, traded with and colonized parts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania and Asia during the Age of Discovery. Sailing ...

mistreatment of the indigenous peoples of the Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

(1521–1821) eventually produced bad-conscience recriminations amongst the European intelligentsias for and against colonialism. As the Roman Catholic Bishop of Chiapas

Chiapas, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas, is one of the states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises Municipalities of Chiapas, 124 municipalities and its capital and large ...

, the priest Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican Order, OP ( ; ); 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a Spanish clergyman, writer, and activist best known for his work as an historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman, then became ...

witnessed the enslavement of the ''indigènes'' of New Spain, yet idealized them into morally innocent noble savages living a simple life in harmony with Mother Nature. At the Valladolid debate

The Valladolid debate (1550–1551 in Spanish ''La Junta de Valladolid'' or ''La Controversia de Valladolid'') was the first moral debate in European history to discuss the rights and treatment of Indigenous people by European colonizers. Held ...

(1550–1551) of the moral philosophy of enslaving the native peoples of the Spanish colonies, Bishop de las Casas reported the noble-savage culture of the natives, especially noting their plain-manner social etiquette

Etiquette ( /ˈɛtikɛt, -kɪt/) can be defined as a set of norms of personal behavior in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviors that accord with the conventions and ...

and that they did not have the social custom of telling lies.

Kingdom of France

In the intellectual debates of the late 16th and 17th centuries, philosophers used the racist stereotypes of the ''savage'' and the ''good savage'' as moral reproaches of the European monarchies fighting theThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

(1618–1648) and the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

(1562–1598). In the essay "Of Cannibals

''Of Cannibals'' (''Des Cannibales''), written circa 1580, is an essay, one of those in the collection ''Essays'', by Michel de Montaigne, describing the ceremonies of the Tupinambá people in Brazil. In particular, he reported about how the group ...

" (1580), Michel de Montaigne reported that the Tupinambá people

The Tupinambá ( Tupinambás) are one of the various Tupi ethnic groups that inhabit present-day Brazil, and who had been living there long before the conquest of the region by Portuguese colonial settlers. The name Tupinambá was also applied t ...

of Brazil ceremoniously eat the bodies of their dead enemies, as a matter of honour, whilst reminding the European reader that such ''wild man'' behavior was analogous to the religious barbarism of burning at the stake

Death by burning is an execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment for and warning agai ...

: "One calls ‘barbarism’ whatever he is not accustomed to." The academic Terence Cave

Terence Christopher Cave (born 1 December 1938) is a British literary scholar.

Life

Terence Cave studied for his Bachelor of Arts and Doctor of Philosophy degrees at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. Cave began his academic career in 196 ...

further explains Montaigne's point of moral philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

:

As philosophic reportage, "Of Cannibals" applies cultural relativism

Cultural relativism is the view that concepts and moral values must be understood in their own cultural context and not judged according to the standards of a different culture. It asserts the equal validity of all points of view and the relati ...

to compare the civilized European to the uncivilized noble savage. Montaigne's anthropological report about cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

in Brazil indicated that the Tupinambá people were neither a noble nor an exceptionally good folk

Folk or Folks may refer to:

Sociology

*Nation

*People

* Folklore

** Folk art

** Folk dance

** Folk hero

** Folk horror

** Folk music

*** Folk metal

*** Folk punk

*** Folk rock

** Folk religion

* Folk taxonomy

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Fo ...

, yet neither were the Tupinambá culturally or morally inferior to his contemporary, 16th-century European civilization. From the perspective of Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited governmen ...

of Montaigne's humanist portrayal of the customs

Customs is an authority or Government agency, agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling International trade, the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out ...

of honor of the Tupinambá people indicates Western philosophic recognition that people are people, despite their different customs, traditions, and codes of honor. The academic David El Kenz explicates Montaigne's background concerning the violence of customary morality:

Literature

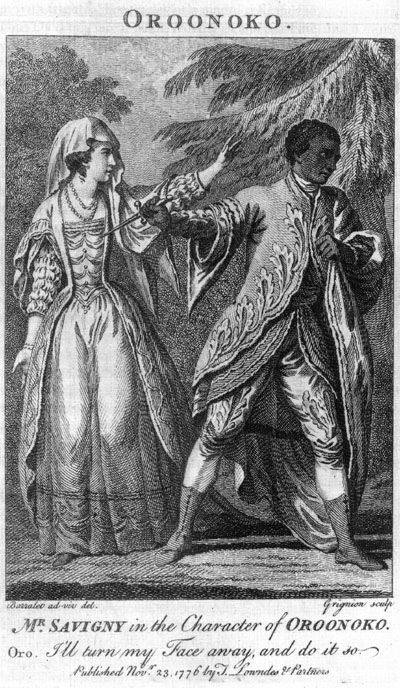

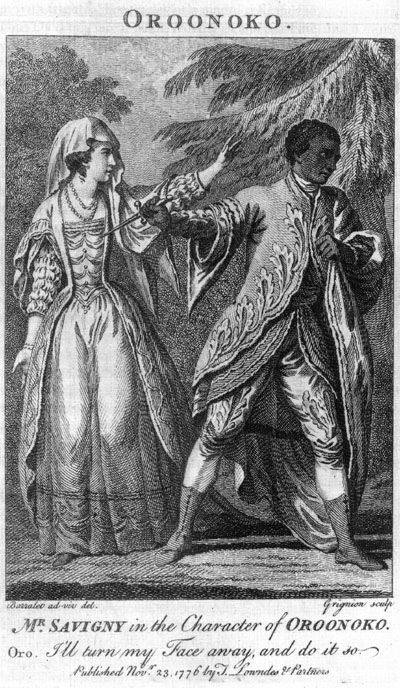

The themes about the person and ''

The themes about the person and ''persona

A persona (plural personae or personas) is a strategic mask of identity in public, the public image of one's personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional Character (arts), character. It is also considered "an intermediary ...

'' of the mythical noble savage are the subjects of the novel '' Oroonoko: Or the Royal Slave'' (1688), by Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; baptism, bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration (England), Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writ ...

, which is the tragic love story between Oroonoko and the beautiful Imoinda, an African king and queen respectively. At Coramantien, Ghana, the protagonist is deceived and delivered into the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

(16th–19th centuries), and Oroonoko becomes a slave of plantation colonists in Surinam (Dutch Guiana, 1667–1954). In the course of his enslavement, Oroonoko meets the woman who narrates to the reader the life and love of Prince Oroonoko, his enslavement, his leading a slave rebellion

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by slaves, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of slaves have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freedom and the dream o ...

against the Dutch planters of Surinam, and his consequent execution by the Dutch colonialists.

Despite Behn having written the popular novel for money, ''Oroonoko'' proved to be political-protest literature against slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, because the story, plot, and characters followed the narrative conventions of the European romance novel

A romance or romantic novel is a genre fiction novel that primarily focuses on the relationship and Romance (love), romantic love between two people, typically with an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending. Authors who have contributed ...

. In the event, the Irish playwright Thomas Southerne

Thomas Southerne (12 February 166026 May 1746) was an Irish dramatist.

Biography

Thomas Southerne, born on 12 February 1660, in Oxmantown, near Dublin, was an Irish dramatist. He was the son of Francis Southerne (a Dublin brewer) and Margare ...

adapted the novel ''Oroonoko'' into the stage play

A play is a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between characters and is intended for theatrical performance rather than mere reading. The creator of a play is known as a playwright.

Plays are staged at various levels, ranging ...

''Oroonoko: A Tragedy'' (1696) that stressed the pathos

Pathos appeals to the emotions and ideals of the audience and elicits feelings that already reside in them. ''Pathos'' is a term most often used in rhetoric (in which it is considered one of the three modes of persuasion, alongside ethos and ...

of the love story, the circumstances, and the characters, which consequently gave political importance to the play and the novel for the candid cultural representation of slave-powered European colonialism.

Uses of the stereotype

Romantic primitivism

In the 1st century CE, in the book ''Germania

Germania ( ; ), also more specifically called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superio ...

'', Tacitus ascribed to the Germans the cultural superiority of the ''noble savage'' way of life, because Rome was too civilized, unlike the savage Germans. The art historian Erwin Panofsky

Erwin Panofsky (March 30, 1892 – March 14, 1968) was a German-Jewish art historian whose work represents a high point in the modern academic study of iconography, including his hugely influential ''Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art ...

explains that:

In the novel '' The Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Ulysses'' (1699), in the “Encounter with the Mandurians” (Chapter IX), the theologian François Fénelon

François de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon, PSS (), more commonly known as François Fénelon (6 August 1651 – 7 January 1715), was a French Catholic archbishop, theologian, poet and writer. Today, he is remembered mostly as the author of ' ...

presented the ''noble savage'' stock character in conversation with civilized men from Europe about possession and ownership of Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

:

In the 18th century, British intellectual debate about Primitivism used the Highland Scots as a local, European example of a mythical ''noble savage'' people, as often as the American Indians were the example. The English cultural perspective scorned the ostensibly rude manners

Etiquette ( /ˈɛtikɛt, -kɪt/) can be defined as a set of norms of personal behavior in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviors that accord with the conventions and n ...

of the Highlanders, whilst admiring and idealizing the toughness of person and character of the Highland Scots; the writer Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett (bapt. 19 March 1721 – 17 September 1771) was a Scottish writer and surgeon. He was best known for writing picaresque novels such as ''The Adventures of Roderick Random'' (1748), ''The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle'' ...

described the Highlanders:

In the Kingdom of France, critics of the Crown and Church risked censorship and summary imprisonment without trial, and primitivism was political protest against the repressive imperial règimes of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

and Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

. In his travelogue of North America, the writer Louis-Armand de Lom d'Arce de Lahontan, Baron de Lahontan

Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan (9 June 1666 – before 1716) was a French aristocrat, writer, and explorer who served in the French military in Canada, where he traveled extensively in the Wisconsin and Minnesota region and the upper Mississip ...

, who had lived with the Huron Indians (Wyandot people

The Wyandot people (also Wyandotte, Wendat, Waⁿdát, or Huron) are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands of the present-day United States and Canada. Their Wyandot language belongs to the Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian language f ...

), ascribed deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

and egalitarian

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

politics to Adario, a Canadian Indian who played the role of noble savage for French explorers:

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was critical of government indifference to thePaxton Boys

The Paxton Boys, also known as the Paxtang Boys or the Paxton Rangers, were a mob of settlers that murdered 20 unarmed Conestoga in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in December 1763. This group of vigilantes from Lancaster and Cumberland counti ...

massacre of the Susquehannock

The Susquehannock, also known as the Conestoga, Minquas, and Andaste, were an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian people who lived in the lower Susquehanna River watershed in what is now Pennsylvania. Their name means “people of the muddy river.”

T ...

in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

Lancaster County (; ), sometimes nicknamed the Garden Spot of America or Pennsylvania Dutch Country, is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 United States ...

in December 1763. Within weeks of the murders, he published ''A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County'', in which he referred to the Paxton Boys as "Christian white savages" and called for judicial punishment of those who carried the Bible in one hand and a hatchet in the other.

When the Paxton Boys led an armed march on Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

in February 1764, with the intent of killing the Moravian Lenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historica ...

and Mohican

The Mohicans ( or ) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that historically spoke an Algonquian language. As part of the Eastern Algonquian family of tribes, they are related to the neighboring Lenape, whose indigenous territory was ...

who had been given shelter there, Franklin recruited associators

Associators were members of 17th- and 18th-century volunteer military associations in the British American thirteen colonies and British Colony of Canada. These were more commonly known as Maryland Protestant, Pennsylvania, and Ameri ...

including Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

to defend the city and led a delegation that met with the Paxton leaders at Germantown outside Philadelphia. The marchers dispersed after Franklin convinced them to submit their grievances in writing to the government.

In his 1784 pamphlet ''Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America'', Franklin especially noted the racism inherent to the colonists using the word ''savage'' as a synonym for indigenous people:

Franklin praised the way of life of indigenous people, their customs of hospitality, their councils of government, and acknowledged that while some Europeans had foregone civilization to live like a "savage", the opposite rarely occurred, because few indigenous people chose "civilization" over "savagery".

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Like the Earl of Shaftesbury in the ''Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit'' (1699),Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

likewise believed that Man is innately good, and that urban civilization, characterized by jealousy, envy, and self-consciousness, has made men bad in character. In '' Discourse on the Origins of Inequality Among Men'' (1754), Rousseau said that in the primordial state of nature

In ethics, political philosophy, social contract theory, religion, and international law, the term state of nature describes the hypothetical way of life that existed before humans organised themselves into societies or civilisations. Philosoph ...

, man was a solitary creature who was not ''méchant'' (bad), but was possessed of an "innate repugnance to see others of his kind suffer."

Moreover, as the ''philosophe

The were the intellectuals of the 18th-century European Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosophers; rathe ...

'' of the Jacobin radicals of the French Revolution (1789–1799), ideologues accused Rousseau of claiming that the mythical ''noble savage'' was a real type of man, despite the term not appearing in work written by Rousseau; in addressing ''The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality'' (1923), the academic Arthur O. Lovejoy said that:

In the ''Discourse on the Origins of Inequality'', Rousseau said that the rise of humanity began a "formidable struggle for existence" between the species man and the other animal species of Nature. That under the pressure of survival emerged ''le caractère spécifique de l'espèce humaine'', the specific quality of character, which distinguishes man from beast, such as intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

capable of "almost unlimited development", and the ''faculté de se perfectionner'', the capability of perfecting himself.

Having invented tools, discovered fire, and transcended the state of nature, Rousseau said that "it is easy to see. . . . that all our labors are directed upon two objects only, namely, for oneself, the commodities of life, and consideration on the part of others"; thus ''amour propre'' (self-regard) is a "factitious feeling arising, only in society, which leads a man to think more highly of himself than of any other." Therefore, "it is this desire for reputation, honors, and preferment which devours us all . . . this rage to be distinguished, that we own what is best and worst in men — our virtues and our vices, our sciences and our errors, our conquerors and our philosophers — in short, a vast number of evil things and a small number of good hings; that is the aspect of character "which inspires men to all the evils which they inflict upon one another."

Men become men only in a civil society based upon law, and only a reformed system of education can make men good; the academic Lovejoy explains that:

Rousseau proposes reorganizing society with a social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

that will "draw from the very evil from which we suffer the remedy which shall cure it"; Lovejoy notes that in the ''Discourse on the Origins of Inequality'', Rousseau:

Charles Dickens

In 1853, in the weekly magazine ''Household Words

''Household Words'' was an English weekly magazine edited by Charles Dickens in the 1850s. It took its name from the line in Shakespeare's '' Henry V'': "Familiar in his mouth as household words."

History

During the planning stages, titles orig ...

'', Charles Dickens published a negative review of the Indian Gallery cultural program, by the portraitist George Catlin

George Catlin ( ; July 26, 1796 – December 23, 1872) was an American lawyer, painter, author, and traveler, who specialized in portraits of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans in the American frontier. Traveling to the Wes ...

, which then was touring England. About Catlin's oil paintings of the North American natives, the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poet, essayist, translator and art critic. His poems are described as exhibiting mastery of rhythm and rhyme, containing an exoticism inherited from the Romantics ...

said that "He atlinhas brought back alive the proud and free characters of these chiefs; both their nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

and manliness."

Despite European idealization of the mythical noble savage as a type of morally superior man, in the essay “The Noble Savage” (1853), Dickens expressed repugnance for the American Indians and their way of life, because they were dirty and cruel and continually quarrelled among themselves. In the satire of romanticised primitivism Dickens showed that the painter Catlin, the Indian Gallery of portraits and landscapes, and the white people who admire the idealized American Indians or the

Despite European idealization of the mythical noble savage as a type of morally superior man, in the essay “The Noble Savage” (1853), Dickens expressed repugnance for the American Indians and their way of life, because they were dirty and cruel and continually quarrelled among themselves. In the satire of romanticised primitivism Dickens showed that the painter Catlin, the Indian Gallery of portraits and landscapes, and the white people who admire the idealized American Indians or the bushmen

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are the members of any of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the Indigenous peoples of Africa, oldest surviving cultures of the region. They are thought to have diverged fro ...

of Africa are examples of the term ''noble savage'' used as a means of Othering

In philosophy, the Other is a fundamental concept referring to anyone or anything perceived as distinct or different from oneself. This distinction is crucial for understanding how individuals construct their own identities, as the encounter wit ...

a person into a racialist stereotype.Moore, "Reappraising Dickens's 'Noble Savage'"(2002): 236–243. Dickens begins by dismissing the mythical noble savage as not being a distinct human being:

Dickens ends his cultural criticism by reiterating his argument against the romanticized ''persona

A persona (plural personae or personas) is a strategic mask of identity in public, the public image of one's personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional Character (arts), character. It is also considered "an intermediary ...

'' of the mythical noble savage:

Theories of racialism

In 1860, the physicianJohn Crawfurd

John Crawfurd (13 August 1783 – 11 May 1868) was a British physician, colonial administrator, diplomat and writer who served as the second and last resident of Singapore.

Early life

He was born on Islay, in Argyll, Scotland, the son of Sam ...

and the anthropologist James Hunt

James Simon Wallis Hunt (29 August 1947 – 15 June 1993) was a British racing driver and broadcaster, who competed in Formula One from to . Nicknamed "the Shunt", Hunt won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in with McLaren, and wo ...

identified the racial stereotype of ''the noble savage'' as an example of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, yet, as advocates of polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that humans are of different origins (polygenesis). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views find little merit ...

— that each race is a distinct species of Man — Crawfurd and Hunt dismissed the arguments of their opponents by accusing them of being proponents of "Rousseau's Noble Savage". Later in his career, Crawfurd re-introduced the ''noble savage'' term to modern anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

and deliberately ascribed coinage of the term to Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Modern perspectives

Supporters of primitivism

In "The Prehistory of Warfare: Misled by Ethnography" (2006), the researchers Jonathan Haas and Matthew Piscitelli challenged the idea that the human species is innately disposed towards being aggressive or is inclined to engage in violent conflict and propose rather that warfare is an occasional activity by a society and is not an inherent part of human culture.See: Moreover, theUNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

's Seville Statement on Violence

The Seville Statement on Violence is a statement on violence that was adopted by an international meeting of scientists, convened by the Spanish National Commission for UNESCO, in Seville, Spain, on 16 May 1986. It was subsequently adopted by UNESC ...

(1986) specifically rejects claims that the human propensity towards violence has a genetic basis.

Anarcho-primitivists

Anarcho-primitivism is an anarchist critique of civilization that advocates a return to non-civilized ways of life through deindustrialization, abolition of the division of labor or specialization, abandonment of large-scale organization and all ...

, such as the philosopher John Zerzan

John Edward Zerzan ( ; born August 10, 1943) is an American anarchist and primitivist author. His works criticize agricultural civilization as inherently oppressive, and advocate drawing upon the ways of life of hunter-gatherers as an inspirat ...

, rely upon a strong ethical dualism

Ethical dualism (from ancient Greek ἔθος (o ἦθος), ethos, "character", "custom", and Latin duo, "two") refers to the practice of imputing evil entirely and exclusively to a specific group of people, while disregarding or denying one's ...

between Anarcho-primitivism and civilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

; hence, "life before domestication ndagriculture was, in fact, largely one of leisure, intimacy with nature, sensual wisdom, sexual equality, and health." Zerzan's claims about the moral superiority of primitive societies are based on a certain reading of the works of anthropologists, such as Marshall Sahlins

Marshall David Sahlins ( ; December 27, 1930April 5, 2021) was an American cultural anthropologist best known for his ethnographic work in the Pacific and for his contributions to anthropological theory. He was the Charles F. Grey Distinguishe ...

and Richard Borshay Lee

Richard Borshay Lee (born 1937) is a Canadian anthropologist. Lee has studied at the University of Toronto and University of California, Berkeley, where he received a Ph.D. He holds a position at the University of Toronto as Professor Emeritus o ...

, wherein the anthropologic category of '' primitive society'' is restricted to hunter-gatherer societies who have no domesticated animals or agriculture, e.g. the stable social hierarchy

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). ...

of the American Indians of the north-west North America, who live from fishing and foraging, is attributed to having domesticated dogs and the cultivation of tobacco, that animal husbandry and agriculture equal civilization.

In anthropology, the argument has been made that key tenets of the myth of the noble savage idea inform cultural investments in places seemingly removed from the Tropics, such as the Mediterranean and specifically Greece, during the debt crisis by European institutions (such as documenta) and by various commentators who found Greece to be a positive inspiration for resistance to austerity policies and the neoliberalism of the EU These commentators' positive embrace of the periphery (their mythical noble savage ideal) is the other side of the mainstream views, also dominant during that period, that stereotyped Greece and the South as lazy and corrupt.

Opponents of primitivism

In '' War Before Civilization: the Myth of the Peaceful Savage'' (1996), the archaeologistLawrence H. Keeley

Lawrence H. Keeley (August 24, 1948 – October 11, 2017) was an American archaeologist best known for pioneering the field of microwear analysis of lithics. He is also known for his 1996 book, ''War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peace ...

said that the "widespread myth" that "civilized humans have fallen from grace from a simple, primeval happiness, a peaceful golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

" is contradicted and refuted by archeologic evidence that indicates that violence was common practice in early human societies. That the ''noble savage'' paradigm has warped anthropological literature to political ends. Moreover, the anthropologist Roger Sandall

Frederick Roger Sandall (18 December 1933 – 11 August 2012) was a New Zealand-born Australian anthropologist, essayist, cinematographer, and scholar. He was a critic of romantic primitivism, which he called designer tribalism, and argued that ...

likewise accused anthropologists of exalting the mythical noble savage above civilized man, by way of ''designer tribalism'', a form of romanticised primitivism that dehumanises Indigenous peoples into the cultural stereotype of the ''indigène'' peoples who live a primitive way of life demarcated and limited by tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

, which discouraged Indigenous peoples from cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's Dominant culture, majority group or fully adopts the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group. The melting pot model is based on this ...

into the dominant Western culture.

In the 2003 book, '' Constant Battles: Why we fight'' written by Steven LeBlanc, a professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other tertiary education, post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin ...

of archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

who specializes in the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

, LeBlanc further documents the mythical notion of primitive non-violence against foreign tribal peoples, internal strife and internecine violence, as well as violence against animals and wildlife. In many of these instances the homicide rate even rose to substantially higher levels than any seen in modernity on a proportionate basis.

See also

* Racism in the work of Charles Dickens * ''Essays'' (Montaigne) *Exoticism

Exoticism (from ''exotic'') is the style or traits considered characteristic of a distant foreign country. In art and design it is a trend where creators become fascinated with ideas and styles from distant regions and draw inspiration from them. ...

* Native Americans in German popular culture

Since the 18th century, Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans have been a topic of fascination in German culture, inspiring literature, art, film and historical reenactment, as well as influencing German ideas and attitudes to ...

* Native American hobbyism in Germany

* Neotribalism

* Objectification

In social philosophy, objectification is the act of treating a person as an object or a thing. Sexual objectification, the act of treating a person as a mere object of sexual desire, is a subset of objectification, as is self-objectification, th ...

* Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

* Pelagianism

Pelagianism is a Christian theological position that holds that the fall did not taint human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve human perfection. Pelagius (), an ascetic and philosopher from the British Isles, ta ...

* Positive stereotype

In social psychology, a positive stereotype refers to a subjectively favourable belief held about a social group. Common examples of positive stereotypes are Asians with better math ability, African Americans with greater athletic ability, and wo ...

* Stereotypes about indigenous peoples of North America

Stereotypes of Indigenous peoples of Canada and the United States of America include many ethnic stereotypes found worldwide which include historical misrepresentations and the oversimplification of hundreds of Indigenous cultures. Negative ster ...

* Racial fetishism

Concepts of race and sexuality have interacted in various ways in different historical contexts. While partially based on physical similarities within groups, race is understood by scientists to be a social construct rather than a biological re ...

* Romantic racism

Romantic racism is a form of racism in which members of a dominant group project their fantasies onto members of oppressed groups. Scholarship has found this view, for example, in Norman Mailer,Breines, Wini (1992). ''Young, White, and Miserabl ...

* Virtuous pagan

Virtuous pagan is a concept in Christian theology that addressed the fate of the unlearned—the issue of nonbelievers who were never evangelized and consequently during their lifetime had no opportunity to recognize Christ, but nevertheless ...

* Feral child

A feral child (also called wild child) is a young individual who has lived isolated from human contact from a very young age, with little or no experience of human care, social behavior, or language. Such children lack the basics of primary and ...

* Wild man

The wild man, wild man of the woods, woodwose or wodewose is a mythical figure and motif that appears in the art and literature of medieval Europe, comparable to the satyr or faun type in classical mythology and to ''Silvanus (mythology), Silvanu ...

* Human zoo

Human zoos, also known as ethnological expositions, were a colonial practice of publicly displaying people, usually in a so-called "natural" or "primitive" state. They were most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries. These displays of ...

* Uncontacted peoples

Uncontacted peoples are groups of Indigenous peoples living without sustained contact with neighbouring communities and the world community. Groups who decide to remain uncontacted are referred to as indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation. Leg ...

Concepts:

* Alterity

In philosophy and anthropology, alterity refers to the state of being "other" or different (Latin ''alter''). It describes the experience of encountering something or someone perceived as distinct from oneself or one's own group. The concept of al ...

* Cultural relativism

Cultural relativism is the view that concepts and moral values must be understood in their own cultural context and not judged according to the standards of a different culture. It asserts the equal validity of all points of view and the relati ...

* Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

* Master-slave dialectic

* Primitive Communism

Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted or gathered are shared with all members of a group in accordance with individual needs. In political sociolo ...

* Social progress

Progress is movement towards a perceived refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. It is central to the philosophy of progressivism, which interprets progress as the set of advancements in technology, science, and social organization effic ...

* State of nature

In ethics, political philosophy, social contract theory, religion, and international law, the term state of nature describes the hypothetical way of life that existed before humans organised themselves into societies or civilisations. Philosoph ...

* Xenocentrism

Xenocentrism is the preference for the cultural practices of other cultures and societies, such as how they live and what they eat, rather than of one's own social way of life. One example is the romanticization of the noble savage in the 18th-cent ...

Cultural examples:

* ''The Blue Lagoon'' (novel)

* ''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931, and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hier ...

''

* ''A High Wind in Jamaica'' (novel)

* Legend of the Rainbow Warriors

Since the early 1970s, a legend of Rainbow Warriors has inspired some environmentalists and hippies with a belief that their movement is the fulfillment of a Native American prophecy. Usually the "prophecy" is claimed to be Hopi or Cree. Howev ...

* ''Lord of the Flies

''Lord of the Flies'' is the 1954 debut novel of British author William Golding. The plot concerns a group of prepubescent British boys who are stranded on an uninhabited island and their disastrous attempts to govern themselves that led to ...

''

* Magical Negro

The Magical Negro is a trope in American cinema, television, and literature. In the cinema of the United States, the Magical Negro is a supporting stock character who comes to the aid of the (usually white) protagonists in a film. Magical Negr ...

* Plastic shaman

Plastic shamans, or plastic medicine people,Hagan, Helene E ''Sonoma Free County Press.'' Accessed 31 Jan 2013. is a pejorative colloquialism applied to individuals who attempt to pass themselves off as shamans, holy people, or other traditional ...

References

Informational notes Citations Further reading * Barnett, Louise. ''Touched by Fire: the Life, Death, and Mythic Afterlife of George Armstrong Custer''. University of Nebraska Press986

Year 986 ( CMLXXXVI) was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* August 17 – Battle of the Gates of Trajan: Emperor Basil II leads a Byzantine expeditionary force (30,000 me ...

2006.

* Barzun, Jacques (2000). ''From Dawn to Decadence

''From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life'' is a book written by Jacques Barzun. Published in 2000, it is a large-scale survey history of trends in history, politics, culture, and ideas in Western civilization, and argues that, ...

: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present''. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 282–294, and passim.

* Bataille, Gretchen, M. and Silet Charles L., editors. Introduction by Vine Deloria, Jr. ''The Pretend Indian: Images of Native Americans in the Movies''. Iowa State University Press, 1980* Berkhofer, Robert F. "The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present"

* Boas, George (933

Year 933 ( CMXXXIII) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* Spring – Hugh of Provence, king of Italy, launches an expedition to Rome to remove the Roman ruler (''princeps'') Albe ...

1966). '' The Happy Beast in French Thought in the Seventeenth Century.'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Press in 1966.

* Boas, George (948

Year 948 ( CMXLVIII) was a leap year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Arab–Byzantine War: Hamdanid forces under Sayf al-Dawla raid into Asia Minor. The Byzantines respond with reprisa ...

1997). ''Primitivism and Related Ideas in the Middle Ages''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

* Bordewich, Fergus M. "Killing the White Man's Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century"

* Bury, J.B. (1920)''The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth''

(Reprint) New York: Cosimo Press, 2008. * Edgerton, Robert (1992). ''Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony.'' New York: Free Press. * Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. (2008

"'He Scarcely Resembles the Real Man': images of the Indian in popular culture".

Website

''Our Legacy''

Material relating to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, found in Saskatchewan cultural and heritage collections. * Ellingson, Ter. (2001). ''The Myth of the Noble Savage'' (Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press). * Fabian, Johannes. ''Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object'' * Fairchild, Hoxie Neale (1928). ''The Noble Savage: A Study in Romantic Naturalism'' (New York) * Fitzgerald, Margaret Mary (

947

Year 947 (Roman numerals, CMXLVII) was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* Summer – A Principality of Hungary, Hungarian army led by Grand Prince Taksony of Hungary, Taksony campaign ...

1976). ''First Follow Nature: Primitivism in English Poetry 1725–1750''. New York: Kings Crown Press. Reprinted New York: Octagon Press.

*

* Hazard, Paul (937

Year 937 ( CMXXXVII) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* A Hungarian army invades Burgundy, and burns the city of Tournus. Then they go southwards to Italy, pillaging the environs of ...

1947). ''The European Mind (1690–1715)''. Cleveland, Ohio: Meridian Books.

* Keeley, Lawrence H. (1996) '' War Before Civilization

''War Before Civilization: the Myth of the Peaceful Savage'' (Oxford University Press, 1996) is a book by Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor of archaeology at the University of Illinois at Chicago who specialized in prehistoric Europe. The book d ...

: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage''. Oxford: University Press.

* Krech, Shepard (2000). ''The Ecological Indian: Myth and History.'' New York: Norton.

* LeBlanc, Steven (2003). ''Constant battles: the myth of the peaceful, noble savage''. New York : St Martin's Press

* Lovejoy, Arthur O. (1923, 1943). "The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality, " Modern Philology Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov., 1923):165–186. Reprinted in ''Essays in the History of Ideas''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948 and 1960.

* Lovejoy, A. O. and Boas, George (935

Year 935 ( CMXXXV) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* Spring – Arnulf I ("the Bad") of Bavaria invades Italy, crossing through the Upper Adige (modern Tyrol). He proceeds ...

1965). ''Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity.'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Books, 1965.

* Lovejoy, Arthur O. and George Boas. (1935). ''A Documentary History of Primitivism and Related Ideas'', vol. 1. Baltimore.

* Moore, Grace (2004). ''Dickens And Empire: Discourses Of Class, Race And Colonialism In The Works Of Charles Dickens (Nineteenth Century Series)''. Ashgate.

* Olupọna, Jacob Obafẹmi Kẹhinde, Editor. (2003) ''Beyond primitivism: indigenous religious traditions and modernity''. New York and London: Routledge

Routledge ( ) is a British multinational corporation, multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, academic journals, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanit ...

. ,

* Pagden, Anthony (1982). ''The Fall of the Natural Man: The American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

* Pinker, Steven (2002). '' The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature''. Viking

* Sandall, Roger (2001). ''The Culture Cult: Designer Tribalism and Other Essays''

* Reinhardt, Leslie Kaye"British and Indian Identities in a Picture by Benjamin West"

''Eighteenth-Century Studies'' 31: 3 (Spring 1998): 283–305 * Rollins, Peter C. and John E. O'Connor, editors (1998). ''Hollywood's Indian : the Portrayal of the Native American in Film.'' Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press. * Tinker, Chaunchy Brewster (1922). ''Nature's Simple Plan: a phase of radical thought in the mid-eighteenth century''. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. * Torgovnick, Marianna (1991). ''Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives'' (Chicago) * Whitney, Lois Payne (1934). ''Primitivism and the Idea of Progress in English Popular Literature of the Eighteenth Century''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press * Wolf, Eric R.(1982). ''Europe and the People without History''. Berkeley: University of California Press.

External links

Massacres during the Wars of Religion: The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre: a foundational event

Louis Menand. "What Comes Naturally". A review of Steven Pinker's ''The Blank Slate'' from ''The New Yorker''

Peter Gay. "Breeding is Fundamental". ''Book Forum''. April / May 2009

{{authority control Stock characters Multiculturalism Anthropology Cultural concepts Anti-indigenous racism Ethnic and racial stereotypes