Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

from May 1937 to May 1940 and

Leader of the Conservative Party from May 1937 to October 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of

appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

, and in particular for his signing of the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

on 30 September 1938, ceding the German-speaking

Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

region of

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

to

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

led by

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. Following the

invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

on 1 September 1939, which marked the beginning of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Chamberlain announced the

declaration of war on Germany two days later and led the United Kingdom through the

first eight months of the war until his resignation as prime minister on 10 May 1940.

After working in business and local government, and after a short spell as

Director of National Service

The Director of National Service or Minister of National Service was a post that existed briefly in the British government. Although a political appointment, the initial holder was Neville Chamberlain who was not a Member of Parliament at the time ...

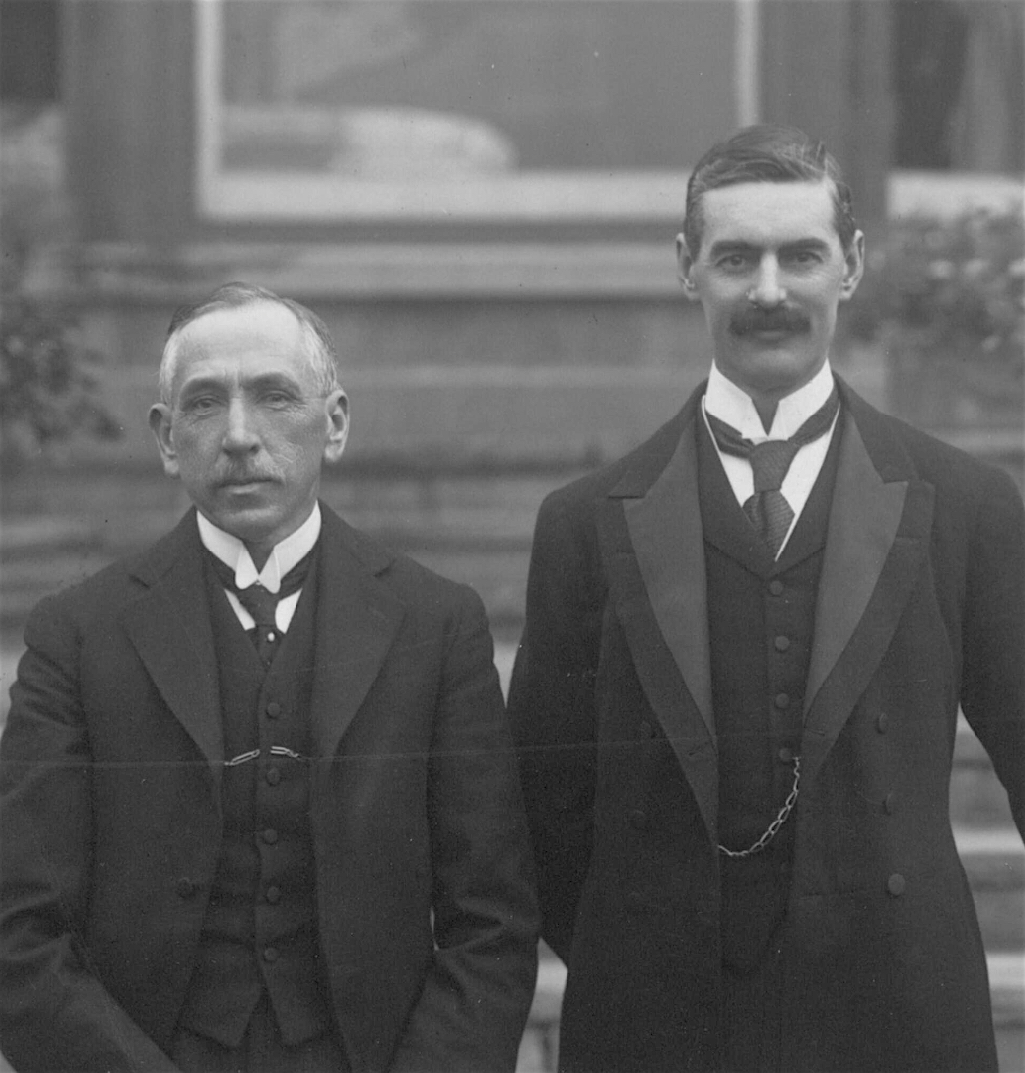

in 1916 and 1917, Chamberlain followed his father

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

and elder half-brother

Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of ...

in becoming a Member of Parliament in the

1918 general election for the new

Birmingham Ladywood

Birmingham Ladywood is a United Kingdom constituencies, constituency in the city of Birmingham that was created in 1918. The seat has been represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the Unit ...

division at the age of 49. He declined a junior ministerial position, remaining a

backbencher

In Westminster system, Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no Minister (government), governmental office and is not a Frontbencher, frontbench spokesperson ...

until 1922. He was rapidly promoted in 1923 to

Minister of Health

A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare spending and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental heal ...

and then

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

. After a short-lived

Labour-led government, he returned as Minister of Health, introducing a range of reform measures from 1924 to 1929. He was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in the

National Government in 1931.

Chamberlain succeeded

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

as prime minister on 28 May 1937. His premiership was dominated by the question of policy towards an increasingly aggressive Germany, and his actions at Munich were widely popular among the British at the time. In response to Hitler's continued aggression, Chamberlain pledged the United Kingdom to defend Poland's independence if the latter were attacked, an alliance that brought his country into declaring war on Germany after it invaded Poland, which resulted in the "Phoney War", but not in any substantial assistance to Poland's fight against the aggression. The

failure of Allied forces to prevent the German invasion of Norway caused the House of Commons to hold the

Norway Debate

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the ''Hansard'' parliamentary archiv ...

in May 1940. Chamberlain's conduct of the war was heavily criticised by members of all parties and, in a vote of confidence, his government's majority was greatly reduced. Accepting that a national government supported by all the main parties was essential, Chamberlain resigned the premiership because the Labour and

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

parties would not serve under his leadership. Although he still led the Conservative Party, he was succeeded as prime minister by his colleague

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

. Until ill health forced him to resign on 22 September 1940, Chamberlain was an important member of the

war cabinet as

Lord President of the Council

The Lord President of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The Lor ...

, heading the government in Churchill's absence. His support for Churchill proved vital during the

May 1940 war cabinet crisis. Chamberlain died aged 71 on 9 November of cancer, six months after leaving the premiership.

Chamberlain's reputation remains controversial among historians, the initial high regard for him being entirely eroded by books such as ''

Guilty Men

''Guilty Men'' is a British polemical book written under the pseudonym "Cato" that was published in July 1940, after the failure of British forces to prevent the defeat and occupation of Norway and France by Nazi Germany. It attacked fifteen publ ...

'', published in July 1940, which blamed Chamberlain and his associates for the Munich accord and for allegedly failing to prepare the country for war. Most historians in the generation following Chamberlain's death held similar views, led by Churchill in ''

The Gathering Storm''. Some later historians have taken a more favourable perspective of Chamberlain and his policies, citing government papers released under the

thirty-year rule

The thirty-year rule (an informal term) is a rule in the laws of the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, and the Commonwealth of Australia that provide that certain government documents will be released publicly thirty years after they were c ...

and arguing that going to war with Germany in 1938 would have been disastrous as the UK was unprepared. Nonetheless, Chamberlain is still

unfavourably ranked amongst British prime ministers.

Early life and political career (1869–1918)

Childhood and businessman

Chamberlain was born on 18 March 1869 in a house called Southbourne in the

Edgbaston

Edgbaston () is a suburb of Birmingham, West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It lies immediately south-west of Birmingham city centre, and was historically in Warwickshire. The Ward (electoral subdivision), wards of Edgbaston and Nort ...

district of

Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

. He was the only son of the second marriage of

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

, who later became

Mayor of Birmingham and a Cabinet minister. His mother was Florence Kenrick, a cousin of

William Kenrick MP; she died when he was a small boy. Joseph Chamberlain had had another son,

Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of ...

, by his first marriage. The Chamberlain family were Unitarian, though Joseph lost personal religious faith by the time Neville was six years old and never required religious adherence of his children.

Neville, who disliked attending worship services of any kind and showed no interest in organised religion, described himself as a Unitarian with no stated faith and also a "reverent agnostic".

Neville Chamberlain was educated at home by his elder sister

Beatrice Chamberlain

Beatrice Chamberlain (25 May 1862 – 19 November 1918) was a British educationalist and political organizer.

Life

Chamberlain was born in Edgbaston in 1862. Her father was Joseph Chamberlain, a local industrialist who later became List of Lord M ...

and later at

Rugby School

Rugby School is a Public school (United Kingdom), private boarding school for pupils aged 13–18, located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire in England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independ ...

. Joseph Chamberlain then sent Neville to

Mason College

Mason Science College was a university college in Birmingham, England, and a predecessor college of the University of Birmingham. Founded in 1875 by industrialist and philanthropist Sir Josiah Mason, the college was incorporated into the Univer ...

, now the

University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university in Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingham (founded in 1825 as ...

. Neville Chamberlain had little interest in his studies there, and in 1889 his father apprenticed him to a firm of accountants. Within six months he became a salaried employee. In an effort to recoup diminished family fortunes, Joseph Chamberlain sent his younger son to establish a

sisal

Sisal (, ; ''Agave sisalana'') is a species of flowering plant native to southern Mexico, but widely cultivated and naturalized in many other countries. It yields a stiff fibre used in making rope and various other products. The sisal fiber is ...

plantation on

Andros Island in the Bahamas. Neville Chamberlain spent six years there but the plantation was a failure, and Joseph Chamberlain lost £50,000 (equivalent to £ in ).

On his return to England, Neville Chamberlain entered business, purchasing (with assistance from his family) Hoskins & Company, a manufacturer of metal ship berths. Chamberlain served as managing director of Hoskins for 17 years during which time the company prospered. He also involved himself in civic activities in Birmingham. In 1906, as Governor of

Birmingham General Hospital

Birmingham General Hospital was a teaching hospital in Birmingham, England, founded in 1779 and closed in the mid-1990s.

History Summer Lane

In 1765, a committee for a proposed hospital, formed by John Ash (physician), John Ash and suppo ...

, and along with "no more than fifteen" other dignitaries, Chamberlain became a founding member of the national United Hospitals Committee of the

British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union and professional body for physician, doctors in the United Kingdom. It does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The BMA ...

.

At forty, Chamberlain was expecting to remain a bachelor, but in 1910 he fell in love with

Anne Cole

Anne Cole is an American swimwear brand most known for the invention of the tankini, a type of swimsuit. The brand's namesake founder, Anne Cole (1926–2017), was the woman who invented the tankini in 1998.

The swimwear company was originally a ...

, a recent connection by marriage, and married her the following year. They met through his Aunt Lilian, the Canadian-born widow of Joseph Chamberlain's brother Herbert, who in 1907 had married Anne Cole's uncle

Alfred Clayton Cole, a director of the

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

.

She encouraged and supported his entry into local politics and was to be his constant companion, helper, and trusted colleague, fully sharing his interests in housing and other political and social activities after his election as an MP. The couple had a son and a daughter.

Entry into politics

Chamberlain initially showed little interest in politics, though his father and half-brother were in Parliament. During the "

Khaki election

In Westminster systems of government, a khaki election is any national election which is heavily influenced by wartime or postwar sentiment. In the British general election of 1900, the Conservative Party government of Lord Salisbury was return ...

" of

1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15 ...

he made speeches in support of Joseph Chamberlain's

Liberal Unionists

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

. The Liberal Unionists were allied with the Conservatives and later merged with them under the name "Unionist Party", which in 1925 became known as the "Conservative and Unionist Party". In 1911, Neville Chamberlain successfully stood as a Liberal Unionist for

Birmingham City Council

Birmingham City Council is the local authority for the city of Birmingham in the West Midlands, England. Birmingham has had an elected local authority since 1838, which has been reformed several times. Since 1974 the council has been a metropo ...

for the All Saints' Ward, located within

his father's parliamentary constituency.

Chamberlain was made chairman of the Town Planning Committee. Under his direction, Birmingham soon adopted one of the first town planning schemes in Britain. The start of the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914 prevented implementation of his plans. In 1915, Chamberlain became

Lord Mayor of Birmingham

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

. Apart from his father Joseph, five of Chamberlain's uncles had also attained the chief Birmingham civic dignity: they were Joseph's brother

Richard Chamberlain

George Richard Chamberlain (March 31, 1934 – March 29, 2025) was an American actor and singer who became a teen idol in the title role of the television show '' Dr. Kildare'' (1961–1966). He subsequently earned the title "King of the Mini- ...

, William and George Kenrick,

Charles Beale, who had been four times Lord Mayor and

Thomas Martineau

The Martineau family is an intellectual, business (banking, breweries, textile manufacturing) and political dynasty associated first with Norwich and later also London and Birmingham, England. Many members of the family have been knighted. Man ...

. As a lord mayor in wartime, Chamberlain had a huge burden of work and he insisted that his councillors and officials work equally hard. He halved the lord mayor's expense allowance and cut back on the number of civic functions expected of the incumbent. In 1915, Chamberlain was appointed a member of the Central Control Board on liquor traffic.

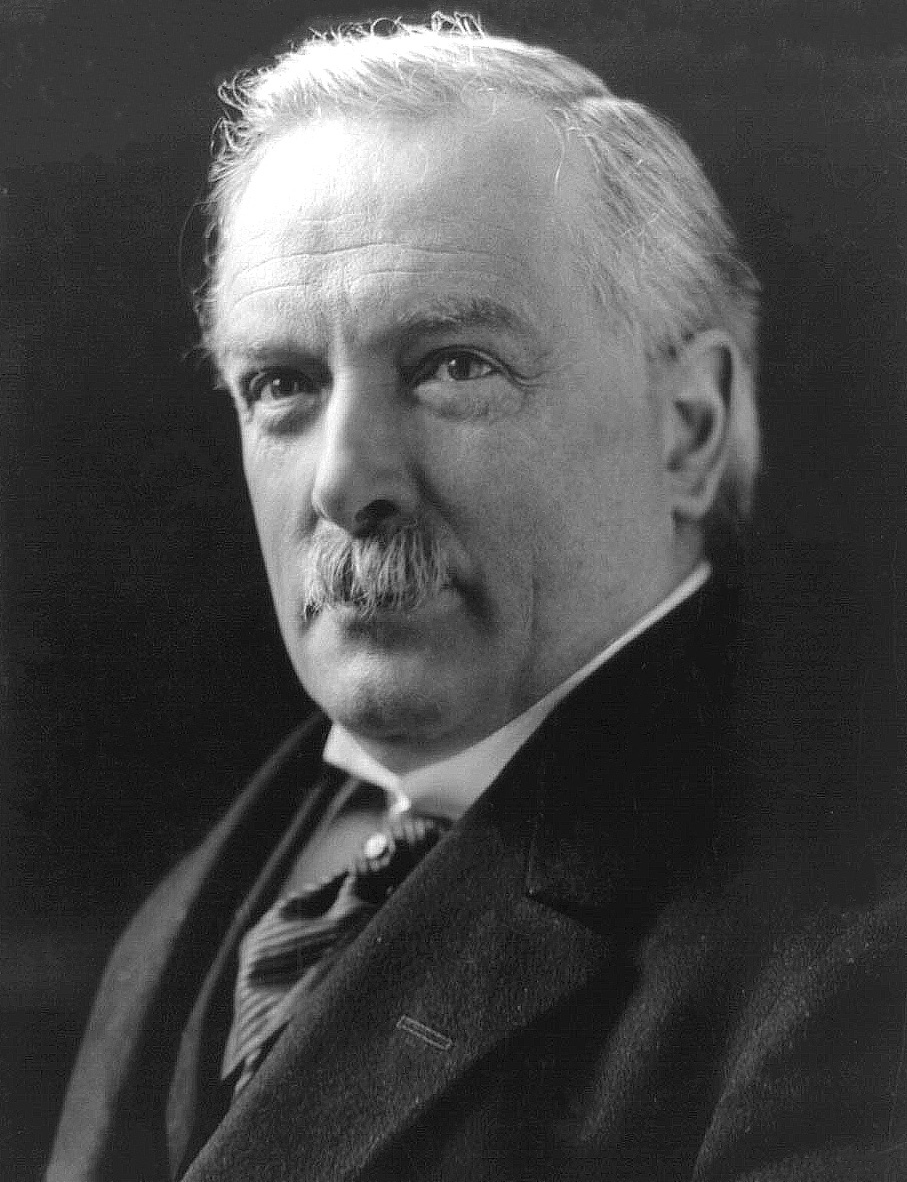

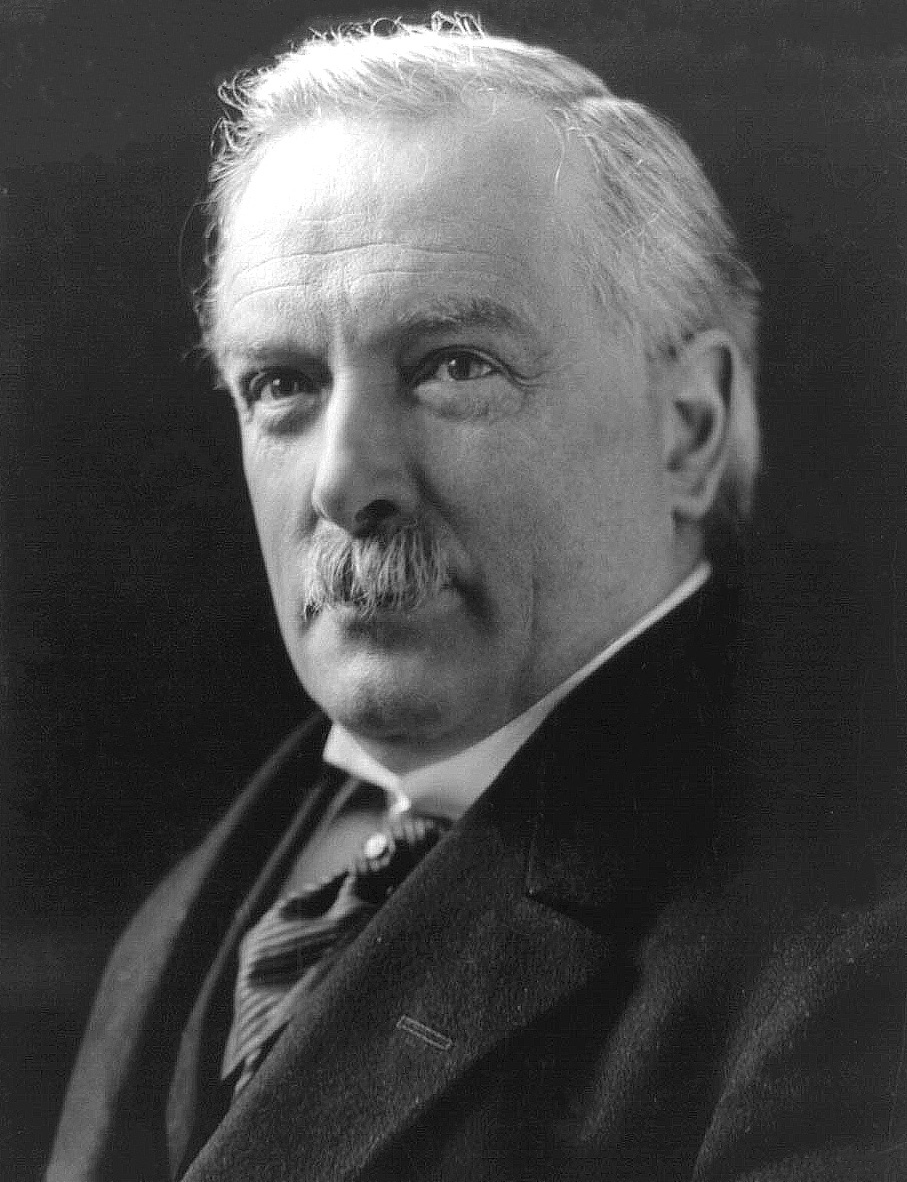

In December 1916, Prime Minister

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

offered Chamberlain the new position of

Director of National Service

The Director of National Service or Minister of National Service was a post that existed briefly in the British government. Although a political appointment, the initial holder was Neville Chamberlain who was not a Member of Parliament at the time ...

, with responsibility for co-ordinating

conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

and ensuring that essential war industries were able to function with sufficient workforces. His tenure was marked by conflict with Lloyd George; in August 1917, having received little support from the Prime Minister, Chamberlain resigned. The relationship between Chamberlain and Lloyd George would, thereafter, be one of mutual hatred.

Chamberlain decided to stand for the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

, and was adopted as Unionist candidate for

Birmingham Ladywood

Birmingham Ladywood is a United Kingdom constituencies, constituency in the city of Birmingham that was created in 1918. The seat has been represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the Unit ...

. After the war ended,

a general election was called almost immediately. The campaign in this constituency was notable because his Liberal Party opponent was

Margery Corbett Ashby

Dame Margery Irene Corbett Ashby, ( Corbett; 19 April 1882 – 15 May 1981) was a British suffragist, Liberal politician, feminist and internationalist.

Background

She was born at Danehill, East Sussex, the daughter of Charles Corbett, a ...

, one of the seventeen women who stood for Parliament at the first election at which women were eligible to do so. Chamberlain reacted to this intervention by being one of the few male candidates to specifically target women voters deploying his wife, issuing a special leaflet headed "A word to the Ladies" and holding two meetings in the afternoon. Chamberlain was elected with almost 70% of the vote and a majority of 6,833. He was 49 years old, which was at the time the greatest age at which any future prime minister had first been elected to the Commons.

MP and minister (1919–1931)

Rise from the backbench

Chamberlain threw himself into parliamentary work, begrudging the times when he was unable to attend debates and spending much time on committee work. He was chairman of the national Unhealthy Areas Committee (1919–21) and in that role, had visited the slums of London, Birmingham, Leeds, Liverpool and Cardiff. Consequently, in March 1920,

Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law (; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a Canadi ...

offered him a junior post at the

Ministry of Health on behalf of the Prime Minister, but Chamberlain was unwilling to serve under Lloyd George and was offered no further posts during Lloyd George's premiership. When Law resigned as party leader, Austen Chamberlain took his place as head of the Unionists in Parliament. Unionist leaders were willing to fight the

1922 election in coalition with the

Lloyd George National Liberals, but on 19 October, Unionist MPs held

a meeting at which they voted to fight the election as a single party. Lloyd George resigned, as did Austen Chamberlain, and Law was recalled from retirement to lead the Unionists as prime minister.

Many high-ranking Unionists refused to serve under Law to the benefit of Chamberlain, who rose over the course of ten months from backbencher to Chancellor of the Exchequer. Law initially appointed Chamberlain

Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters.

History

The practice of having a government official ...

and Chamberlain was sworn of the

Privy Council.

When

Arthur Griffith-Boscawen

Sir Arthur Sackville Trevor Griffith-Boscawen PC (18 October 1865 – 1 June 1946) was a British politician in the Conservative Party whose career was cut short by losing a string of Parliamentary elections.

Biography

Sir Arthur was born at ...

, the Minister of Health, lost his seat in the 1922 election and was defeated in a by-election in March 1923 by future

home secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

James Chuter Ede

James Chuter Chuter-Ede, Baron Chuter-Ede, (; 11 September 1882 – 11 November 1965), was a British teacher, trade unionist and Labour Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) for 32 years, and served as the sole Home Secretary u ...

, Law offered the position to Chamberlain. Two months later, Law was diagnosed with advanced, terminal throat cancer. He immediately resigned and was replaced by Chancellor of the Exchequer

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

. In August 1923, Baldwin promoted Chamberlain to the position of Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Chamberlain served only five months in the office before the Conservatives were defeated at the

1923 general election.

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

became the first-ever Labour prime minister, but his government fell within months, necessitating

another general election. By a margin of only 77 votes, Chamberlain narrowly defeated the Labour candidate,

Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980), was a British aristocrat and politician who rose to fame during the 1920s and 1930s when he, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, turned to fascism. ...

, who later led the

British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

. Believing he would lose if he stood again in Birmingham Ladywood, Chamberlain arranged to be adopted for

Birmingham Edgbaston

Birmingham Edgbaston is a constituency, represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 2017 by Preet Gill, a Labour Co-op MP.

The most high-profile MP for the constituency was former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (1937–19 ...

, the district of the city where he was born and which was a much safer seat, which he would hold for the rest of his life. The Unionists won the election, but Chamberlain declined to serve again as chancellor, preferring his former position as Minister of Health.

Within two weeks of his appointment as Minister of Health, Chamberlain presented the Cabinet with an agenda containing 25 pieces of legislation he hoped to see enacted. Before he left office in 1929, 21 of the 25 bills had passed into law. Chamberlain sought the abolition of the elected

Poor Law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

Boards of Guardians

Boards of guardians were ''ad hoc'' authorities that administered Poor Law in the United Kingdom from 1835 to 1930.

England and Wales

Boards of guardians were created by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, replacing the parish overseers of the poor ...

which administered relief—and which in some areas were responsible for

rates

Rate or rates may refer to:

Finance

* Rate (company), an American residential mortgage company formerly known as Guaranteed Rate

* Rates (tax), a type of taxation system in the United Kingdom used to fund local government

* Exchange rate, rate ...

. Many of the boards were controlled by Labour, and such boards had defied the government by distributing relief funds to the able-bodied unemployed. In 1929, Chamberlain initiated the

Local Government Act 1929

The Local Government Act 1929 ( 19 & 20 Geo. 5. c. 17) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that made changes to the Poor Law and local government in England and Wales.

The act abolished the system of poor law unions in England ...

to abolish the Poor Law boards entirely. Chamberlain spoke in the Commons for two and a half hours on the

second reading

A reading of a bill is a stage of debate on the bill held by a general body of a legislature.

In the Westminster system, developed in the United Kingdom, there are generally three readings of a bill as it passes through the stages of becoming ...

of the bill, and when he concluded he was applauded by all parties. The bill was passed into law.

Though Chamberlain struck a conciliatory note during the

1926 General Strike

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British government ...

, in general he had poor relations with the Labour opposition. Future Labour prime minister

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

complained that Chamberlain "always treated us like dirt," and in April 1927 Chamberlain wrote: "More and more do I feel an utter contempt for their lamentable ''stupidity''." His poor relations with the Labour Party later played a major part in his downfall as prime minister.

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1931–1937)

Baldwin called

a general election for 30 May 1929, resulting in a

hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system (typically employing Majoritarian representation, majoritarian electoral systems) to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing ...

with Labour holding the most seats. Baldwin and his government resigned and Labour, under MacDonald, again took office. In 1931, the MacDonald government faced a serious crisis as the

May Report The May Report, within the economic history of the United Kingdom, was a publication on 31 July 1931 by the Committee on National Expenditure ("May Committee"). The May Committee was set up to suggest ways for the government to curb expenditure afte ...

revealed that the budget was unbalanced, with an expected shortfall of £120 million. The Labour government resigned on 24 August, and MacDonald formed a

National Government supported by most Conservative MPs. Chamberlain once again returned to the Ministry of Health.

After the

1931 general election, in which supporters of the National Government (mostly Conservatives) won an overwhelming victory, MacDonald designated Chamberlain as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Chamberlain proposed a 10% tariff on foreign goods and lower or no tariffs on goods from the colonies and the

Dominions

A dominion was any of several largely self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of colonial self-governance increased (and, in ...

. Joseph Chamberlain had advocated a similar policy, "

Imperial Preference

Imperial Preference was a system of mutual tariff reduction enacted throughout the British Empire and British Commonwealth following the Ottawa Conference of 1932. As Commonwealth Preference, the proposal was later revived in regard to the member ...

"; Neville Chamberlain laid his bill before the House of Commons on 4 February 1932, and concluded his address by noting the appropriateness of his seeking to enact his father's proposal. At the end of the speech, Austen Chamberlain walked down from the backbenches and shook his brother's hand. The

Import Duties Act 1932

The Import Duties Act 1932 ( 22 & 23 Geo. 5. c. 8) was an Act of United Kingdom Parliament. The Act introduced a general tariff of 10% on most imports, though some foodstuffs, raw materials, and some imports from the British Empire were exempted. ...

passed Parliament easily.

Chamberlain presented his first budget in April 1932. He maintained the severe budget cuts that had been agreed at the inception of the National Government. Interest on the war debt was a major cost. Chamberlain reduced the annual interest rate on

most of Britain's war debt from 5% to 3.5%. Between 1932 and 1938, Chamberlain halved the percentage of the budget devoted to interest on the war debt.

War debt

Chamberlain hoped that a cancellation of the war debt owed to the United States could be negotiated. In June 1933, Britain hosted the

World Monetary and Economic Conference, which came to nothing as US president

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

sent word that he would not consider any war

debt cancellation. By 1934, Chamberlain was able to declare a budget surplus and reverse many of the cuts in unemployment compensation and civil servant salaries he had made after taking office. He told the Commons, "We have now finished the story of ''

Bleak House

''Bleak House'' is a novel by English author Charles Dickens, first published as a 20-episode Serial (literature), serial between 12 March 1852 and 12 September 1853. The novel has many characters and several subplots, and is told partly by th ...

'' and are sitting down this afternoon to enjoy the first chapter of ''

Great Expectations

''Great Expectations'' is the thirteenth novel by English author Charles Dickens and his penultimate completed novel. The novel is a bildungsroman and depicts the education of an orphan nicknamed Pip. It is Dickens' second novel, after ''Dav ...

''."

Welfare spending

The Unemployed Assistance Board (UAB, established by the

Unemployment Act 1934

The Unemployment Act 1934 ( 24 & 25 Geo. 5. c. 29) (part 1 was also known as the Unemployment Insurance Act 1934 and part 2 as the Unemployment Assistance Act 1934), was an act of Parliament in the United Kingdom, reaching statute on 28 June 1934 ...

) was largely Chamberlain's creation, and he wished to see the issue of unemployment assistance removed from party political argument.

Moreover, Chamberlain "saw the importance of 'providing some interest in life for the large numbers of men never likely to get work', and out of this realisation was to come the responsibility of the UAB for the 'welfare', not merely the maintenance, of the unemployed."

Defence spending

Defence spending had been heavily cut in Chamberlain's early budgets. By 1935, faced with

a resurgent Germany under Hitler's leadership, he was convinced of the need for rearmament. Chamberlain especially urged the strengthening of the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

, realising that Britain's historical bulwark, the

English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

, was no defence against air power.

In 1935, MacDonald stood down as prime minister, and Baldwin became prime minister for the third time. In the

1935 general election, the Conservative-dominated National Government lost 90 seats from its massive 1931 majority, but still retained an overwhelming majority of 255 in the House of Commons. During the campaign, deputy Labour leader

Arthur Greenwood

Arthur Greenwood (8 February 1880 – 9 June 1954) was a British politician. A prominent member of the Labour Party from the 1920s until the late 1940s, Greenwood rose to prominence within the party as secretary of its research department fr ...

had attacked Chamberlain for spending money on rearmament, saying that the rearmament policy was "the merest scaremongering; disgraceful in a statesman of Mr Chamberlain's responsible position, to suggest that more millions of money needed to be spent on armaments."

Role in the abdication crisis

Chamberlain is believed to have had a significant role in the

1936 abdication crisis. He wrote in his diary that

Wallis Simpson

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Spencer and then Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986) was an American socialite and the wife of Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor (former King Edward VIII). Their intentio ...

, Edward VIII's intended wife, was "an entirely unscrupulous woman who is not in love with the King but is exploiting him for her own purposes. She has already ruined him in money and jewels ..." In common with the rest of the Cabinet, except

Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, (22 February 1890 – 1 January 1954), known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician and diplomat who was also a military and political historian and writer.

First elected to Parl ...

, he agreed with Baldwin that the King should abdicate if he married Simpson, and on 6 December he and Baldwin both stressed that the King should make his decision before Christmas; by one account, he believed that the uncertainty was "hurting the Christmas trade".

The King abdicated on 10 December, four days after the meeting.

Soon after the abdication Baldwin announced that he would remain until shortly after the

coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

The coronation of the British monarch, coronation of George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, Elizabeth, as King of the United Kingdom, king and List of British royal consorts, queen of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realm, ...

. On 28 May, two weeks after the Coronation, Baldwin resigned, advising the King to send for Chamberlain. Austen did not live to see his brother's appointment as prime minister having died two months earlier.

Prime Minister (1937–1940)

Upon his appointment, Chamberlain considered calling a general election, but with three and a half years remaining in the current Parliament's term he decided to wait. At 68 he was the second-oldest person in the 20th century (after

Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman ( né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and Leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1908. ...

) to become prime minister for the first time, and was widely seen as a caretaker who would lead the Conservative Party until the next election and then step down in favour of a younger man, with Foreign Secretary

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

a likely candidate. From the start of Chamberlain's premiership a number of would-be successors were rumoured to be jockeying for position.

Chamberlain had disliked what he considered to be the overly sentimental attitude of both Baldwin and MacDonald on Cabinet appointments and reshuffles. Although he had worked closely with the

President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. A committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, it was first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centur ...

,

Walter Runciman, on the tariff issue, Chamberlain dismissed him from his post, instead offering him the token position of

Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

, which an angry Runciman declined. Chamberlain thought Runciman, a member of the

Liberal National Party, to be lazy. Soon after taking office Chamberlain instructed his ministers to prepare two-year policy programmes. These reports were to be integrated with the intent of co-ordinating the passage of legislation through the current Parliament, the term of which was to expire in November 1940.

At the time of his appointment, Chamberlain's personality was not well known to the public, though he had made annual budget broadcasts for six years. According to Chamberlain biographer Robert Self, these appeared relaxed and modern, showing an ability to speak directly to the camera. Chamberlain had few friends among his parliamentary colleagues; an attempt by his

parliamentary private secretary, Lord Dunglass (later prime minister himself as

Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel ( ; 2 July 1903 – 9 October 1995), known as Lord Dunglass from 1918 to 1951 and the Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

), to bring him to the Commons Smoking Room to socialise with colleagues ended in embarrassing silence. Chamberlain compensated for these shortcomings by devising the most sophisticated

press management system employed by a prime minister up to that time, with officials at

Number 10, led by his chief of press George Steward, convincing members of the press that they were colleagues sharing power and insider knowledge, and should espouse the government line.

Domestic policy

Chamberlain saw his elevation to the premiership as the final glory in a career as a domestic reformer, not realising that he would be remembered for foreign policy decisions. One reason he sought the settlement of European issues was the hope it would allow him to concentrate on domestic affairs.

Soon after attaining the premiership, Chamberlain obtained passage of the

Factories Act 1937

The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom beginning in 1802 to regulate and improve the conditions of industrial employment.

The early acts concentrated on regulating the hours of work and moral welf ...

. This Act was aimed at bettering working conditions in factories, and placed limits on the working hours of women and children. In 1938, Parliament enacted the

Coal Act 1938, which allowed for nationalisation of coal deposits. Another major law passed that year was the

Holidays with Pay Act 1938. Though the Act only recommended that employers give workers a week off with pay, it led to a great expansion of

holiday camp

A holiday camp is a type of holiday accommodation, primarily in the United Kingdom, that encourages holidaymakers to stay within the site boundary, and provides entertainment and facilities for them throughout the day. Since the 1970s, the term ...

s and other leisure accommodation for the working classes. The Housing Act 1938 provided subsidies aimed at encouraging

slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low-income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

and maintained

rent control

Rent regulation is a system of laws for the rental market of dwellings, with controversial effects on affordability of housing and tenancies. Generally, a system of rent regulation involves:

*Price controls, limits on the rent that a landlord ...

. Chamberlain's plans for the reform of local government were shelved because of the outbreak of war in 1939. Likewise, the raising of the school-leaving age to 15, scheduled for implementation on 1 September 1939, did not go into effect.

Relations with Ireland

Relations between the United Kingdom and the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

had been strained since the 1932 appointment of

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

as

President of the Executive Council. The

Anglo-Irish Trade War

The Anglo-Irish Trade War (also called the Economic War) was a retaliatory trade war between the Irish Free State and the United Kingdom from 1932 to 1938. The Irish government refused to continue reimbursing Britain with land annuities from f ...

, sparked by the withholding of money that Ireland had agreed to pay the United Kingdom, had caused economic losses on both sides, and the two nations were anxious for a settlement. The de Valera government also sought to sever the remaining ties between Ireland and the UK, such as ending the King's status as Irish Head of State. As chancellor, Chamberlain had taken a hard-line stance against concessions to the Irish, but as premier sought a settlement with Ireland, being persuaded that the strained ties were affecting relations with other Dominions.

Talks had been suspended under Baldwin in 1936 but resumed in November 1937. De Valera sought not only to alter the constitutional status of Ireland, but to overturn other aspects of the

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, most notably the issue of

partition, as well as obtaining full control of the three

Treaty Ports

Treaty ports (; ) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China (before th ...

which had remained in British control. Britain, on the other hand, wished to retain the Treaty Ports, at least in time of war, and to obtain the money that Ireland had agreed to pay.

The Irish proved very tough negotiators, so much so that Chamberlain complained that one of de Valera's offers had "presented United Kingdom ministers with a three-leafed shamrock, none of the leaves of which had any advantages for the UK." With the talks facing deadlock, Chamberlain made the Irish a final offer in March 1938 which acceded to many Irish positions, though he was confident that he had "only given up the small things", and the agreements were signed on 25 April 1938. The issue of partition was not resolved, but the Irish agreed to pay £10 million to the British. There was no provision in the treaties for British access to the Treaty Ports in time of war, but Chamberlain accepted de Valera's oral assurance that in the event of war the British would have access. Conservative backbencher

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

attacked the agreements in Parliament for surrendering the Treaty Ports, which he described as the "sentinel towers of the

Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

". When war came, de Valera denied Britain access to the Treaty Ports under

Irish neutrality. Churchill railed against these treaties in ''

The Gathering Storm'', stating that he "never saw the House of Commons more completely misled" and that "members were made to feel very differently about it when our existence hung in the balance during the

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

." Chamberlain believed that the Treaty Ports were unusable if Ireland was hostile, and deemed their loss worthwhile to assure friendly relations with Dublin.

Foreign policy

Early days (May 1937 – March 1938)

Chamberlain sought to conciliate Germany and make the Nazi state a partner in a stable Europe. He believed Germany could be satisfied by the restoration of some of its colonies, and during the

Rhineland crisis of March 1936 he had stated that "if we were in sight of an all-round settlement the British government ought to consider the question" of restoration of colonies.

The new prime minister's attempts to secure such a settlement were frustrated because Germany was in no hurry to talk to Britain. Foreign Minister

Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German politician, diplomat and convicted Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble famil ...

was supposed to visit Britain in July 1937 but cancelled his visit.

Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He h ...

, the

Lord President of the Council

The Lord President of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The Lor ...

, visited Germany privately in November and met Hitler and other German officials. Both Chamberlain and British Ambassador to Germany

Nevile Henderson

Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson (10 June 1882 – 30 December 1942) was a British diplomat who served as the ambassador of the United Kingdom to Nazi Germany, Germany from 1937 to 1939.

Early life and education

Henderson was born at Sedgwick, Wes ...

pronounced the visit a success. Foreign Office officials complained that the Halifax visit made it appear Britain was too eager for talks, and the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, felt that he had been bypassed.

Chamberlain also bypassed Eden while the latter was on holiday by opening direct talks with Italy, an international pariah for its

invasion and conquest of

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

. At a Cabinet meeting on 8 September 1937, Chamberlain indicated that he saw "the lessening of the tension between this country and Italy as a very valuable contribution toward the pacification and appeasement of Europe" which would "weaken the

Rome–Berlin axis

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Germany, Kingdom of Italy ...

." Chamberlain also set up a private line of communication with the Italian ''Duce''

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

through the Italian Ambassador, Count

Dino Grandi

Dino Grandi, 1st Conte di Mordano (4 June 1895 – 21 May 1988), was an Italian Fascist politician, minister of justice, minister of foreign affairs and president of Parliament.

Early life

Born at Mordano, province of Bologna, Grandi was ...

.

In February 1938, Hitler began to press the Austrian government to accept ''

Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, ), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "German Question, Greater Germany") arose after t ...

'' or joining Germany and Austria into a single state. Chamberlain believed that it was essential to cement relations with Italy in the hope that an Anglo–Italian alliance would forestall Hitler from imposing his rule over Austria. Eden believed that Chamberlain was being too hasty in talking with Italy and holding out the prospect of ''

de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' recognition of Italy's conquest of Ethiopia. Chamberlain concluded that Eden would have to accept his policy or resign. The Cabinet heard both men out but unanimously decided for Chamberlain, and despite efforts by other Cabinet members to prevent it, Eden resigned from office. In later years, Eden tried to portray his resignation as a stand against appeasement (Churchill described him in ''The Second World War'' as "one strong young figure standing up against long, dismal, drawling tides of drift and surrender") but many ministers and MPs believed there was no issue at stake worth resignation. Chamberlain appointed Lord Halifax as foreign secretary in Eden's place.

Road to Munich (March 1938 – September 1938)

In March 1938, Austria became a part of Germany in the ''Anschluss''. Though the beleaguered Austrians requested help from Britain, none was forthcoming. Britain did send Berlin a strong note of protest without specifying any actual action that the British government might take. In addressing the Cabinet shortly after German forces crossed the border, Chamberlain placed blame on both Germany and Austria. Chamberlain noted,

On 14 March, the day after the ''Anschluss'', Chamberlain addressed the House of Commons and strongly condemned the methods used by the Germans in the takeover of Austria. Chamberlain's address met with the approval of the House.

With Austria absorbed by Germany, attention turned to Hitler's obvious next target, the

Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

region of Czechoslovakia. With three million ethnic Germans, the Sudetenland represented the largest German population outside the ''Reich'' and Hitler began to call for the union of the region with Germany. Britain had no military obligations toward Czechoslovakia, but France and Czechoslovakia had a mutual assistance pact and both the French and Czechoslovaks also had an alliance with the Soviet Union. After the fall of Austria, the Cabinet's Foreign Policy Committee considered seeking a "grand alliance" to thwart Germany or, alternatively, an assurance to France of assistance if the French went to war. Instead, the committee chose to advocate that Czechoslovakia be urged to make the best terms it could with Germany. The full Cabinet agreed with the committee's recommendation, influenced by a report from the chiefs of staff stating that there was little that Britain could do to help the Czechs in the event of a German invasion. Chamberlain reported to an amenable House that he was unwilling to limit his government's discretion by giving commitments.

Britain and Italy signed an agreement on 16 April 1938. In exchange for ''de jure'' recognition of Italy's Ethiopian conquest, Italy agreed to withdraw some Italian "volunteers" from the Nationalist (pro-

Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

* Franco of Cologne (mid to late 13th cent ...

) side of the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

. By this point, the Nationalists strongly had the upper hand in that conflict, and they completed their victory the following year. Later that month, the new French prime minister,

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical Party (France), Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, who was the Prime Minister of France in 1933, 1934 and again from 1938 to 1940. he signed the Munich Agreeme ...

, came to London for talks with Chamberlain, and agreed to follow the British position on Czechoslovakia.

In May, Czech border guards shot two Sudeten German farmers who were trying to cross the border from Germany into Czechoslovakia without stopping for border controls. This incident caused unrest among the Sudeten Germans, and Germany was then said to be moving troops to the border. In response to the report, Prague moved troops to the German border. Halifax sent a note to Germany warning that if France intervened in the crisis on Czechoslovakia's behalf, Britain might support France. Tensions appeared to calm, and Chamberlain and Halifax were applauded for their "masterly" handling of the crisis. Though it was not known at the time, it later became clear that Germany had had no plans for a May invasion of Czechoslovakia. Nonetheless, the Chamberlain government received strong and almost unanimous support from the British press.

Negotiations between the Czech government and the Sudeten Germans dragged on through mid-1938. They achieved little result; Sudeten leader

Konrad Henlein

Konrad Ernst Eduard Henlein (6 May 1898 – 10 May 1945) was a Sudeten German politician in Czechoslovakia before World War II. After Germany invaded Czechoslovakia he became the and of Reichsgau Sudetenland under the occupation of Nazi Germa ...

was under private instructions from Hitler not to reach an agreement. On 3 August, Walter Runciman (by now Lord Runciman) travelled to Prague as a

mediator

Mediation is a structured, voluntary process for resolving disputes, facilitated by a neutral third party known as the mediator. It is a structured, interactive process where an independent third party, the mediator, assists disputing parties ...

sent by the British government. Over the next two weeks, Runciman met separately with Henlein, Czechoslovak president

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1939 to 1948. During the first six years of his second stint, he led the Czec ...

, and other leaders, but made no progress. On 30 August, Chamberlain met his Cabinet and Ambassador Henderson and secured their backing—with only

First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

Duff Cooper dissenting against Chamberlain's policy to pressure Czechoslovakia into making concessions, on the grounds that Britain was then in no position to back up any threat to go to war.

Chamberlain realised that Hitler would likely signal his intentions in his 12 September speech at the annual

Nuremberg Rally

The Nuremberg rallies ( , meaning ) were a series of celebratory events coordinated by the Nazi Party and held in the German city of Nuremberg from 1923 to 1938. The first nationwide party convention took place in Munich in January 1923, but the ...

, and so he discussed with his advisors how to respond if war seemed likely. In consultation with his close advisor

Horace Wilson, Chamberlain set out "Plan Z". If war seemed inevitable, Chamberlain would fly to Germany to negotiate directly with Hitler.

September 1938: Munich

Preliminary meetings

Lord Runciman continued his attempts to pressure the Czechoslovak government into concessions. On 7 September there was an altercation involving Sudeten members of the Czechoslovak parliament in the North Moravian city of

Ostrava

Ostrava (; ; ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 283,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four rivers: Oder, Opava (river), Opa ...

(''Mährisch-Ostrau'' in German). The Germans made considerable propaganda out of the incident, though the Prague government tried to conciliate them by dismissing Czech police who had been involved. As the tempest grew, Runciman concluded that there was no point in attempting further negotiations until after Hitler's speech. The mission never resumed.

There was tremendous tension in the final days before Hitler's speech on the last day of the Rally, as Britain, France, and Czechoslovakia all partially mobilised their troops. Thousands gathered outside 10 Downing Street on the night of the speech. At last Hitler addressed his wildly enthusiastic followers:

The following morning, 13 September, Chamberlain and the Cabinet were informed by Secret Service sources that all German embassies had been told that Germany would invade Czechoslovakia on 25 September. Convinced that the French would not fight (Daladier was privately proposing a three-Power summit to settle the Sudeten question), Chamberlain decided to implement "Plan Z" and sent a message to Hitler that he was willing to come to Germany to negotiate. Hitler accepted and Chamberlain flew to Germany on the morning of 15 September; this was the first time, excepting a short jaunt at an industrial fair, that Chamberlain had ever flown. Chamberlain flew to Munich and then travelled by rail to Hitler's retreat at

Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden () is a municipality in the district Berchtesgadener Land, Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, near the border with Austria, south of Salzburg and southeast of Munich. It lies in the Berchtesgaden Alps. South of the town, the Be ...

, (see

Berchtesgaden meeting

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the German annexation of part of Czechoslovakia called the Sudeten ...

).

The face-to-face meeting lasted about three hours. Hitler demanded the annexation of the Sudetenland, and through questioning him, Chamberlain was able to obtain assurances that Hitler had no designs on the remainder of Czechoslovakia or on the areas in Eastern Europe which had German minorities. After the meeting Chamberlain returned to London, believing that he had obtained a breathing space during which agreement could be reached and the peace preserved. Under the proposals made at Berchtesgaden the Sudetenland would be annexed by Germany if a plebiscite in the Sudetenland favoured it. Czechoslovakia would receive international guarantees of its independence which would replace existing treaty obligations—principally the French pledge to the Czechoslovaks. The French agreed to the requirements. Under considerable pressure the Czechoslovaks also agreed, causing the Czechoslovak government to fall.

Chamberlain flew back to Germany, meeting Hitler in

Bad Godesberg

Bad Godesberg () is a borough () of Bonn, southern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. From 1949 to 1999, while Bonn was the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany, most foreign embassies were in Bad Godesberg. Some buildings are still used as br ...

on 22 September. Hitler brushed aside the proposals of the previous meeting, saying "that won't do any more". Hitler demanded immediate occupation of the Sudetenland and that Polish and Hungarian territorial claims on Czechoslovakia be addressed. Chamberlain objected strenuously, telling Hitler that he had worked to bring the French and Czechoslovaks into line with Germany's demands, so much so that he had been accused of giving in to dictators and had been booed on his departure that morning. Hitler was unmoved.

That evening, Chamberlain told Lord Halifax that the "meeting with Herr Hitler had been most unsatisfactory". The following day, Hitler kept Chamberlain waiting until mid-afternoon, when he sent a five-page letter, in German, outlining the demands he had made orally the previous day. Chamberlain replied by offering to act as an intermediary with the Czechoslovaks, and suggested that Hitler put his demands in a memorandum which could be circulated to the French and Czechoslovaks.

The leaders met again late on the evening of 23 September—a meeting that stretched into the early morning hours. Hitler demanded that fleeing Czechs in the zones to be occupied take nothing with them. He extended his deadline for occupation of the Sudetenland to 1 October—the date he had long before secretly set for the invasion of Czechoslovakia. The meeting ended amicably, with Chamberlain confiding to Hitler his hopes they would be able to work out other problems in Europe in the same spirit. Hitler hinted that the Sudetenland fulfilled his territorial ambitions in Europe. Chamberlain flew back to London, saying "It is up to the Czechs now."

Munich conference

Hitler's proposals met with resistance not only from the French and Czechoslovaks, but also from some members of Chamberlain's cabinet. With no agreement in sight, war seemed inevitable. Chamberlain issued a press statement calling on Germany to abandon the threat of force in exchange for British help in obtaining the concessions it sought. On the evening of 27 September, Chamberlain addressed the nation by radio, and after thanking those who wrote to him, stated:

On 28 September, Chamberlain called on Hitler to invite him to Germany again to seek a solution through a summit involving the British, French, Germans, and Italians. Hitler replied favourably, and word of this response came to Chamberlain as he was winding up a speech in the House of Commons which sat in gloomy anticipation of war. Chamberlain informed the House of this in his speech. The response was a passionate demonstration, with members cheering Chamberlain wildly. Even diplomats in the galleries applauded. Lord Dunglass later commented, "There were a lot of appeasers in Parliament that day."

On the morning of 29 September Chamberlain left

Heston Aerodrome

Heston Aerodrome was an airfield located to the west of London, England, operational between 1929 and 1947. It was situated on the border of the Heston and Cranford areas of Hounslow, Middlesex. In September 1938, the British Prime Minister, ...

(to the east of today's

Heathrow Airport

Heathrow Airport , also colloquially known as London Heathrow Airport and named ''London Airport'' until 1966, is the primary and largest international airport serving London, the capital and most populous city of England and the United Kingdo ...

) for his third and final visit to Germany. On arrival in Munich the British delegation was taken directly to the ''

Führerbau

The Führerbau ("the Führer's building") is a historically significant building at Arcisstrasse 12 in Maxvorstadt, Munich. It was built between 1933 and 1937, during the Nazi Germany, Nazi period, and used extensively by Adolf Hitler. Unlike ma ...

'', where Daladier, Mussolini, and Hitler soon arrived. The four leaders and their translators held an informal meeting; Hitler said that he intended to invade Czechoslovakia on 1 October. Mussolini distributed a proposal similar to Hitler's Bad Godesberg terms. In reality, the proposal had been drafted by German officials and transmitted to Rome the previous day. The four leaders debated the draft and Chamberlain raised the question of compensation for the Czechoslovak government and citizens, but Hitler refused to consider this.

The leaders were joined by advisors after lunch, and hours were spent on long discussions of each clause of the "Italian" draft agreement. Late that evening the British and French left for their hotels, saying that they had to seek advice from their respective capitals. Meanwhile, the Germans and Italians enjoyed the feast which Hitler had intended for all the participants. During this break, Chamberlain advisor Horace Wilson met with the Czechoslovaks; he informed them of the draft agreement and asked which districts were particularly important to them. The conference resumed at about 10 pm and was mostly in the hands of a small drafting committee. At 1:30 am the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

was ready for signing, though the signing ceremony was delayed when Hitler discovered that the ornate inkwell on his desk was empty.

Chamberlain and Daladier returned to their hotel and informed the Czechoslovaks of the agreement. The two prime ministers urged quick acceptance by the Czechoslovaks of the agreement, since the evacuation by the Czechs was to begin the following day. At 12:30 pm the Czechoslovak government in Prague objected to the decision but agreed to its terms.

Aftermath and reception

Before leaving the ''Führerbau'', Chamberlain requested a private conference with Hitler. Hitler agreed, and the two met at Hitler's apartment in the city later that morning. Chamberlain urged restraint in the implementation of the agreement and requested that the Germans not bomb Prague if the Czechs resisted, to which Hitler seemed agreeable. Chamberlain took from his pocket a paper headed "Anglo–German Agreement", which contained three paragraphs, including a statement that the two nations considered the Munich Agreement "symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war again." According to Chamberlain, Hitler interjected "''Ja! Ja!''" ("Yes! Yes!"). The two men signed the paper then and there. When, later that day, German foreign minister

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

remonstrated with Hitler for signing it, the Führer replied, "Oh, don't take it so seriously. That piece of paper is of no further significance whatever." Chamberlain, on the other hand, patted his breast pocket when he returned to his hotel for lunch and said, "I've got it!" Word leaked of the outcome of the meetings before Chamberlain's return, causing delight among many in London but gloom for Churchill and his supporters.

Chamberlain returned to London in triumph. Large crowds mobbed Heston, where he was met by the

Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Households of the United Kingdom, Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Monarchy of the United Ki ...

,

the Earl of Clarendon

Earl of Clarendon is a title that has been created twice in British history, in 1661 and 1776.

The family seat is Holywell House, near Swanmore, Hampshire.

First creation of the title

The title was created for the first time in the Peera ...

, who gave him a letter from

King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

assuring him of the Empire's lasting gratitude and urging him to come straight to

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

to report. The streets were so packed with cheering people that it took Chamberlain an hour and a half to journey the from Heston to the Palace. After reporting to the King, Chamberlain and his wife appeared on the Palace balcony with the King and

Queen

Queen most commonly refers to:

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a kingdom

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen (band), a British rock band

Queen or QUEEN may also refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Q ...

. He then went to Downing Street; both the street and the front hall of Number 10 were packed. As he headed upstairs to address the crowd from a first-floor window, someone called to him, "Neville, go up to the window and say 'peace for our time'." Chamberlain turned around and responded, "No, I don't do that sort of thing." Nevertheless, in his statement to the crowd, Chamberlain recalled the words of his predecessor,

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, upon the latter's return from the

Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

:

King George issued a statement to his people, "After the magnificent efforts of the Prime Minister in the cause of peace it is my fervent hope that a new era of friendship and prosperity may be dawning among the peoples of the world." When the King met Duff Cooper, who resigned as First Lord of the Admiralty over the Munich Agreement, he told Cooper that he respected people who had the courage of their convictions, but could not agree with him. He wrote to his mother,

Queen Mary, that "the Prime Minister was delighted with the results of his mission, as are we all." She responded to her son with anger against those who spoke against Chamberlain: "He brought home peace, why can't they be grateful?" Most newspapers supported Chamberlain uncritically, and he received thousands of gifts, from a silver dinner service to many of his trademark umbrellas.

The Commons discussed the Munich Agreement on 3 October. Though Cooper opened by setting forth the reasons for his resignation and Churchill spoke harshly against the pact, no Conservative voted against the government. Only between 20 and 30 abstained, including Churchill, Eden, Cooper, and

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

.

Path to war (October 1938 – August 1939)

In the aftermath of Munich, Chamberlain continued to pursue a course of cautious rearmament. He told the Cabinet in early October 1938, "