Neo-colonialists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally

In 1961, regarding the economic mechanism of neocolonial control, in the speech ''Cuba: Historical Exception or Vanguard in the Anti-colonial Struggle?'', Argentine revolutionary

In 1961, regarding the economic mechanism of neocolonial control, in the speech ''Cuba: Historical Exception or Vanguard in the Anti-colonial Struggle?'', Argentine revolutionary

The

The

One variant of neocolonialism theory critiques ''

One variant of neocolonialism theory critiques ''

The Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks

* Stuart J. Seborer. ''U.S. neo-colonialism in Africa'' (

Mbeki warns on China-Africa ties

*

''Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism'', by Kwame Nkrumah, originally published 1965

at Marxists Internet Archive.

"Africa 'should not pay its debts – BBC

July 6, 2004.

Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs video (ram) – hosted by Columbia Univ.

by Gloria Emeagwali.

: Joseph Hill,

Studying African development history: Study guides

Lauri Siitonen, Päivi Hasu, Wolfgang Zeller.

independent state

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of a ...

(usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to the continuing dependence of former colonies on foreign countries, but its meaning soon broadened to apply, more generally, to places where the power of developed countries was used to produce a colonial-like exploitation.

Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism

Theories of imperialism are a range of theoretical approaches to understanding the expansion of capitalism into new areas, the unequal development of different countries, and economic systems that may lead to the dominance of some countries over ...

, globalization

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

, cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism (also cultural colonialism) comprises the culture, cultural dimensions of imperialism. The word "imperialism" describes practices in which a country engages culture (language, tradition, ritual, politics, economics) to creat ...

and conditional aid to influence or control a developing country instead of the previous colonial methods of direct military control or indirect political control (hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

). Neocolonialism differs from standard globalisation and development aid

Development aid (or development cooperation) is a type of aid given by governments and other agencies to support the economic, environmental, social, and political International development, development of developing countries. It is distinguishe ...

in that it typically results in a relationship of dependence, subservience, or financial obligation towards the neocolonialist nation.

Coined by the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

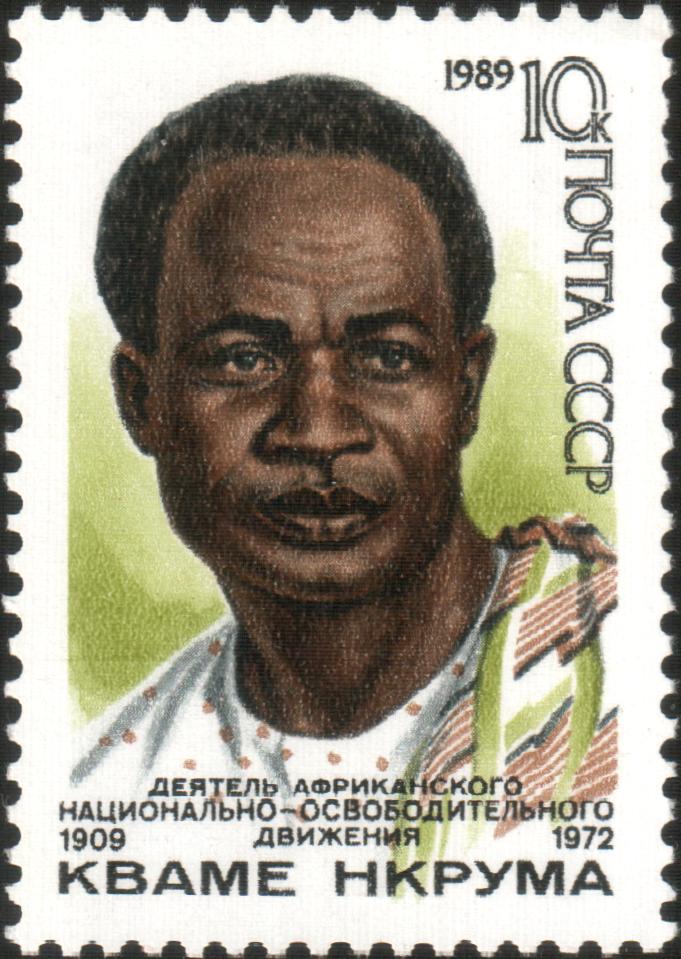

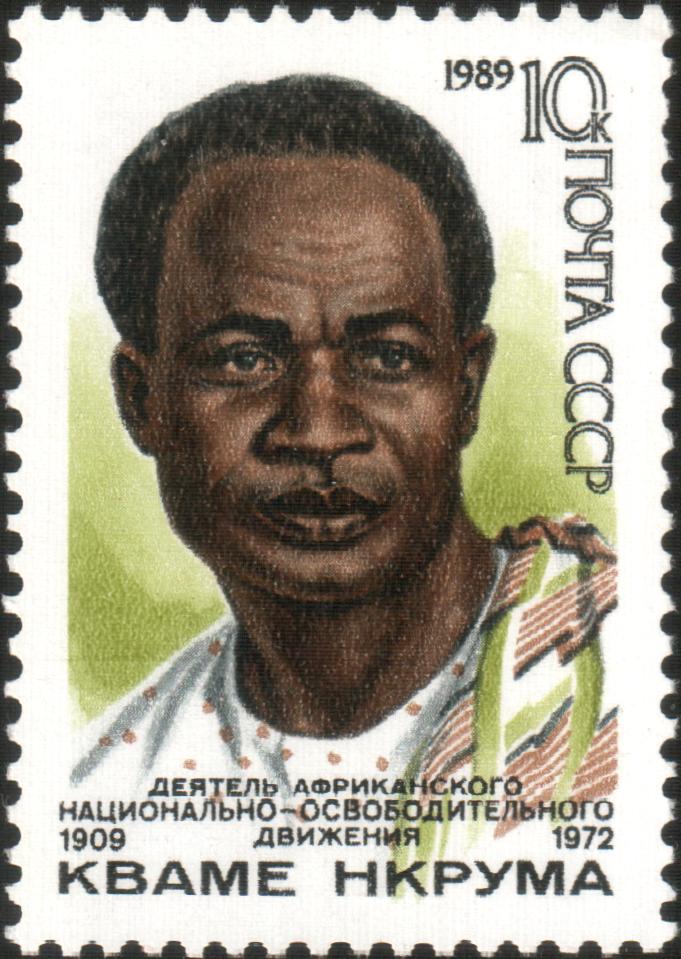

in 1956, it was first used by Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

in the context of African countries undergoing decolonisation in the 1960s. Neocolonialism is also discussed in the works of Western thinkers such as Sartre (''Colonialism and Neocolonialism

''Colonialism and Neocolonialism'' by Jean-Paul Sartre (first published in French in 1964) is a controversial and influential critique of French policies in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a c ...

'', 1964) and Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

('' The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism'', 1979).

Term

Origins

When first proposed, the term neocolonialism was applied to European countries' continued economic and cultural relationships with their former colonies, those African countries that had been liberated in the aftermath ofSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. At the 1962 National Union of Popular Forces

The National Union of Popular Forces (; , UNFP) was a political party in Morocco founded in 1959 in Morocco by Mehdi Ben Barka and others. It opposed the monarchy and it was closely associated with the labour movement, the student movement (partic ...

conference, Mehdi Ben Barka

Mehdi Ben Barka (; 1920 – disappeared 29 October 1965) was a Moroccan nationalist, Arab socialist, politician, revolutionary, anti-imperialist, head of the left-wing National Union of Popular Forces (UNFP) and secretary of the Tricontinenta ...

, the Moroccan political organizer and later chair of the Tricontinental Conference 1966

The Tricontinental Conference was a gathering of countries that focused on anti-colonial and anti-imperial issues during the Cold War era, specifically those related to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The conference was held from 3rd to 16 Janu ...

, used the term ''al-isti'mar al-jadid'' ( "the new colonialism") to describe the political trends in Africa in the early sixties.

Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

, president of Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

from 1960 to 1966, is credited with coining the term, which appeared in the 1963 preamble of the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

Charter, and was the title of his 1965 book, '' Neo-Colonialism, The Last Stage of Imperialism''. In his book the President of Ghana exposes the workings of International monopoly capitalism in Africa. For him Neo-colonialism, insidious and complex, is even more dangerous than the old colonialism and shows how meaningless political freedom can be without economic independence. Nkrumah theoretically developed and extended to the post–World War II 20th century the socio-economic and political arguments presented by Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

in the pamphlet ''Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

''Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism'', originally published as ''Imperialism, the Newest Stage of Capitalism'', is a book written by Vladimir Lenin in 1916 and published in 1917. It describes the formation of oligopoly, by the interlac ...

'' (1917). The pamphlet frames 19th-century imperialism as the logical extension of geopolitical

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of states: ''de facto'' independen ...

power, to meet the financial investment needs of the political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

.

In ''Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism'', Kwame Nkrumah wrote:

Neocolonial economic dominance

In 1961, regarding the economic mechanism of neocolonial control, in the speech ''Cuba: Historical Exception or Vanguard in the Anti-colonial Struggle?'', Argentine revolutionary

In 1961, regarding the economic mechanism of neocolonial control, in the speech ''Cuba: Historical Exception or Vanguard in the Anti-colonial Struggle?'', Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

said:

Dependency theory

Dependency theory

Dependency theory is the idea that resources flow from a " periphery" of poor and exploited states to a " core" of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former. A central contention of dependency theory is that poor states ...

is the theoretical description of economic neocolonialism. It proposes that the global economic system comprises wealthy countries at the centre, and poor countries at the periphery. Economic neocolonialism extracts the human and natural resources of a poor country to flow to the economies of the wealthy countries. It claims that the poverty of the peripheral countries is the result of how they are integrated in the global economic system. Dependency theory derives from the Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

analysis of economic inequalities within the world's system of economies, thus, under-development of the periphery is a direct result of development in the centre. It includes the concept of the late 19th century semi-colony

In Marxist theory, a semi-colony is a country which is officially recognized as a politically independent state and as a sovereign nation, but which is in reality dependent on and/or dominated by another ( imperialist) country (or, in some cases ...

. It contrasts the Marxist perspective of the theory of colonial dependency with capitalist economics. The latter proposes that poverty is a development stage in the poor country's progress towards full integration in the global economic system. Proponents of dependency theory, such as Venezuelan historian Federico Brito Figueroa, who investigated the socioeconomic bases of neocolonial dependency, influenced the thinking of the former President of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (; ; 28 July 1954 – 5 March 2013) was a Venezuelan politician, Bolivarian Revolution, revolutionary, and Officer (armed forces), military officer who served as the 52nd president of Venezuela from 1999 until De ...

.

Cold War

During the mid-to-late 20th century, in the course of the ideological conflict between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., each country and itssatellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

s accused each other of practising neocolonialism in their imperial and hegemonic

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' ...

pursuits. Provides the standard definition of "Neo-colonialism" specific to the US and European colonialism. Defines "neo-colonialism" as a capitalist phenomenon. Defines "neo-colonialism" on page 7. Provides the history of the word "neo-colonialism" as an anti-capitalist term (p. 339); also applicable to the U.S.S.R. (p. 322). The struggle included proxy war

In political science, a proxy war is an armed conflict where at least one of the belligerents is directed or supported by an external third-party power. In the term ''proxy war'', a belligerent with external support is the ''proxy''; both bel ...

s, fought by client states in the decolonised countries. Cuba, the Warsaw Pact bloc, Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

(1956–1970) ''et al.'' accused the U.S. of sponsoring anti-democratic governments whose regimes did not represent the interests of their people and of overthrowing elected governments (African, Asian, Latin American) that did not support U.S. geopolitical interests.

In the 1960s, under the leadership of Chairman Mehdi Ben Barka

Mehdi Ben Barka (; 1920 – disappeared 29 October 1965) was a Moroccan nationalist, Arab socialist, politician, revolutionary, anti-imperialist, head of the left-wing National Union of Popular Forces (UNFP) and secretary of the Tricontinenta ...

, the Cuban Tricontinental Conference

The Tricontinental Conference was a gathering of countries that focused on anti-colonial and anti-imperial issues during the Cold War era, specifically those related to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The conference was held from 3rd to 16 Janu ...

(Organisation of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America) recognised and supported the validity of revolutionary anti-colonialism

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholars of decolon ...

as a means for colonised peoples of the Third World to achieve self-determination, a policy which angered the U.S. and France. Moreover, Chairman Barka headed the Commission on Neocolonialism, which dealt with the work to resolve the neocolonial involvement of colonial powers in decolonised counties; and said that the U.S., as the leading capitalist country of the world, was, in practise, the principal neocolonialist political actor.

Multinational corporations

Critics of the practice of neocolonialism also argue that investment bymultinational corporation

A multinational corporation (MNC; also called a multinational enterprise (MNE), transnational enterprise (TNE), transnational corporation (TNC), international corporation, or stateless corporation, is a corporate organization that owns and cont ...

s enriches few in underdeveloped countries and causes humanitarian

Humanitarianism is an ideology centered on the value of human life, whereby humans practice benevolent treatment and provide assistance to other humans to reduce suffering and improve the conditions of humanity for moral, altruistic, and emotiona ...

, environmental

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, referring respectively to all living and non-living things occurring naturally and the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism ...

and ecological

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere levels. Ecology overlaps with the closely re ...

damage to their populations. They argue that this results in unsustainable development and perpetual underdevelopment. These countries remain reservoirs of cheap labor and raw materials, while restricting access to advanced production techniques to develop their own economies. In some countries, monopolization of natural resources, while initially leading to an influx of investment, is often followed by increases in unemployment, poverty and a decline in per-capita income.

In the West African nations of Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and Mauritania, fishing was historically central to the economy. Beginning in 1979, the European Union began negotiating contracts with governments for fishing off the coast of West Africa. Unsustainable commercial over-fishing by foreign fleets played a significant role in large-scale unemployment and migration of people across the region. This violates the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international treaty that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 169 sov ...

, which recognises the importance of fishing to local communities and insists that government fishing agreements with foreign companies should target only surplus stocks.

Oxfam

Oxfam is a British-founded confederation of 21 independent non-governmental organizations (NGOs), focusing on the alleviation of global poverty, founded in 1942 and led by Oxfam International. It began as the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief ...

's 2024 report "Inequality, Inc" concludes that multinational corporations located in the Global North

Global North and Global South are terms that denote a method of grouping countries based on their defining characteristics with regard to socioeconomics and Global politics, politics. According to UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Global S ...

are "perpetuating a colonial style 'extractivist' model" across the Global South as the economies of the latter "are locked into exporting primary commodities, from copper to coffee" to these multinationals.

International borrowing

American economistJeffrey Sachs

Jeffrey David Sachs ( ; born November 5, 1954) is an American economist and public policy analyst who is a professor at Columbia University, where he was formerly director of The Earth Institute. He worked on the topics of sustainable develop ...

recommended that the entire African debt (c. US$200 billion) be dismissed, and recommended that African nations not repay either the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

or the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

(IMF):

Conservation and neocolonialism

Wallerstein, and separately Frank, claim that the modernconservation movement

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the ...

, as practiced by international organisations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is a Swiss-based international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named th ...

, inadvertently developed a neocolonial relationship with underdeveloped nations.

Science

Former colonial powers and Africa

Françafrique

The representative example of European neocolonialism is ''Françafrique

In international relations, () is France's sphere of influence (or in French, meaning 'backyard') over former French and (also French-speaking) Belgian colonies in sub-Saharan Africa. The term was derived from the expression , which was use ...

'', the "France-Africa" constituted by the continued close relationships between France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and its former African colonies.

In 1955, the initial usage of the term "French Africa", by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny (; 18 October 1905 – 7 December 1993), affectionately called Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux ("The Old One"), was an Ivorian politician and physician who served as the first List of heads of state of Ivory Coast, pr ...

of Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest List of ci ...

, denoted positive social, cultural and economic Franco–African relations.

It was later applied by neocolonialism critics to describe an imbalanced international relation.

Neocolonialism was used to describe a type of foreign intervention in countries belonging to the Pan-Africanist

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the Trans-Sa ...

movement, as well as the Asian–African Conference of Bandung (1955), which led to the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

(1961).

Neocolonialism was formally defined by the All-African Peoples' Conference

The All-African Peoples Conference (AAPC) was partly a corollary and partly a different perspective to the modern Africa states represented by the First Conference of Independent Africa States held in 1957. In contrast to this first meeting where o ...

(AAPC) and published in the ''Resolution on Neo-colonialism''. At both the Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

conference (1960) and the Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

conference (1961), AAPC described the actions of the French Community

The French Community () was the constitutional organization set up in October 1958 between France and its remaining African colonies, then in the process of decolonization. It replaced the French Union, which had reorganized the colonial em ...

of independent states, organised by France, as neocolonial.

The politician Jacques Foccart, the principal adviser for African matters to French presidents Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

(1958–1969) and Georges Pompidou

Georges Jean Raymond Pompidou ( ; ; 5 July 19112 April 1974) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1969 until his death in 1974. He previously served as Prime Minister of France under President Charles de Gaulle from 19 ...

(1969–1974), was the principal proponent of ''Françafrique''.

The works of Verschave and Beti reported a forty-year, post-independence relationship with France's former colonial peoples, which featured colonial garrisons ''in situ'' and monopolies by French multinational corporation

A multinational corporation (MNC; also called a multinational enterprise (MNE), transnational enterprise (TNE), transnational corporation (TNC), international corporation, or stateless corporation, is a corporate organization that owns and cont ...

s, usually for the exploitation of mineral resources. It was argued that the African leaders with close ties to France—especially during the Soviet–American Cold War (1945–1992)—acted more as agents of French business and geopolitical

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of states: ''de facto'' independen ...

interests than as the national leaders of sovereign states. Cited examples are Omar Bongo

Omar Bongo Ondimba (born Albert-Bernard Bongo; 30 December 1935 – 8 June 2009) was a Gabonese politician who was the second president of Gabon from 1967 until Death and state funeral of Omar Bongo, his death in 2009. A member of the Gabonese De ...

(Gabon

Gabon ( ; ), officially the Gabonese Republic (), is a country on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, on the equator, bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north, the Republic of the Congo to the east and south, and ...

), Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast), Gnassingbé Eyadéma

Gnassingbé Eyadéma (; born Étienne Eyadéma Gnassingbé, 26 December 1935 – 5 February 2005) was a Togolese military officer and politician who served as the third president of Togo from 1967 until his death in 2005, after which he was immed ...

(Togo

Togo, officially the Togolese Republic, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to Ghana–Togo border, the west, Benin to Benin–Togo border, the east and Burkina Faso to Burkina Faso–Togo border, the north. It is one of the le ...

), Denis Sassou-Nguesso

Denis Sassou Nguesso (born 23 November 1943) is a Congolese politician and former military officer who has served as president of the Republic of the Congo since 1997. He also previously served as president from 1979 to 1992.

Sassou Nguesso hea ...

(Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo), is a country located on the western coast of Central ...

), Idriss Déby

Idriss Déby Itno ( '; 18 June 1952 – 20 April 2021) was a Chadian politician and military officer who was the sixth List of heads of state of Chad, president of Chad from 1991 until his death in 2021 during the 2021 Northern Chad offensive, No ...

(Chad

Chad, officially the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North Africa, North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to Chad–Libya border, the north, Sudan to Chad–Sudan border, the east, the Central Afric ...

), and Hamani Diori

Hamani Diori (6 June 1916 – 23 April 1989) was the first President of the Republic of Niger. He was appointed to that office in 1960, when Niger gained independence from France. Although corruption was a common feature of his administration, ...

(Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

).

Belgian Congo

Belgium's approach to Belgian Congo has been characterized as a quintessential example of neocolonialism, as the Belgians embraced rapid decolonization of the Congo with the expectation that the newly independent state would become dependent on Belgium. This dependence would allow the Belgians to exert control over Congo, even though Congo was formally independent. After the decolonisation ofBelgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

continued to control, through the , an estimated 70% of the Congolese economy following the decolonisation process. The most contested part was in the province of Katanga where the , part of the , controlled the mineral-resource-rich province. After a failed attempt to nationalise the mining industry in the 1960s, it was reopened to foreign investment.

United States

There is an ongoing debate about whether certain actions by the United States should be considered neocolonialism. Nayna J. Jhaveri, writing in '' Antipode'', views the 2003 invasion of Iraq as a form of "petroimperialism", believing that the U.S. was motivated to go to war to attain vital oil reserves, rather than to pursue the U.S. government's officialrationale for the Iraq War

There are various Explanation, rationales that have been used to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Iraq War, and subsequent hostilities.

The Presidency of George W. Bush, George W. Bush administration began actively pressing for military ...

.

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

has been a prominent critic of "American imperialism

U.S. imperialism or American imperialism is the expansion of political, economic, cultural, media, and military influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright mi ...

"; he believes that the basic principle of the foreign policy of the United States

The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the bureaus and offices in the United States Department of State, as mentioned in the ''Foreign Policy Agenda'' of the Department of State, are ...

is the establishment of "open societies" that are economically and politically controlled by the United States and where U.S.-based businesses can prosper. He argues that the U.S. seeks to suppress any movements within these countries that are not compliant with U.S. interests and to ensure that U.S.-friendly governments are placed in power. He believes that official accounts of U.S. operations abroad have consistently whitewashed U.S. actions in order to present them as having benevolent motives in spreading democracy. Examples he regularly cites are the actions of the United States in Vietnam, the Philippines, Latin America, and the Middle East.

Chalmers Johnson

Chalmers Ashby Johnson (August 6, 1931 – November 20, 2010) was an American political scientist specializing in comparative politics, and professor emeritus of the University of California, San Diego. He served in the Korean War, was a consult ...

argued in 2004 that America's version of the colony is the military base. Johnson wrote numerous books, including three examinations of the consequences of what he called the " American Empire". Chip Pitts argued similarly in 2006 that enduring United States bases in Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

suggested a vision of " Iraq as a colony".

David Vine, author of ''Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Overseas Harm America and the World'' (2015), said the US had bases in 45 "less-than-democratic" countries and territories. He quotes political scientist Kent Calder: "The United States tends to support dictators nd other undemocratic regimesin nations where it enjoys basing facilities".

China

ThePeople's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

has built increasingly strong ties with some African, Asian, European and Latin American nations which has led to accusations of colonialism, As of August 2007, an estimated 750,000 Chinese nationals were working or living for extended periods in Africa. In the 1980s and 90s, China continued to purchase natural resources—petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil or simply oil, is a naturally occurring, yellowish-black liquid chemical mixture found in geological formations, consisting mainly of hydrocarbons. The term ''petroleum'' refers both to naturally occurring un ...

and minerals—from Africa to fuel the Chinese economy and to finance international business enterprises. In 2006, trade had increased to $50 billion expanding to $500 billion by 2016.

In Africa, China has loaned $95.5 billion to various countries between 2000 and 2015, the majority being spent on power generation and infrastructure. Cases in which this has ended with China acquiring foreign land have led to accusations of "debt-trap diplomacy

Debt-trap diplomacy is a term to describe an international financial relationship where a creditor country or institution extends debt to a borrowing nation partially, or solely, to increase the lender's political leverage. The creditor country ...

". Other analysts say that China's activities "are goodwill for later investment opportunities or an effort to stockpile international support for contentious political issues".

In 2018, Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

n Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad

Mahathir bin Mohamad (; ; born 10 July 1925) is a Malaysian politician, author and doctor who was respectively the fourth and seventh Prime Minister of Malaysia, prime minister of Malaysia from 1981 to 2003 and from 2018 to 2020. He was the ...

cancelled two China-funded projects. He also talked about fears of Malaysia becoming "indebted" and of a "new version of colonialism". He later clarified that he did not refer to the Belt and Road Initiative

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI or B&R), known in China as the One Belt One Road and sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road, is a global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the government of China in 2013 to invest in more t ...

or China with this.

According to Mark Langan in 2017, China, Western actors, and other emerging powers pursue their own interests at the expense of African interests. Western actors depict China as a threat to Africa, while depicting European and American involvement in Africa as being virtuous.

Russia

Russia currently occupies parts of neighboring states. These occupied territories areTransnistria

Transnistria, officially known as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic and locally as Pridnestrovie, is a Landlocked country, landlocked Transnistria conflict#International recognition of Transnistria, breakaway state internationally recogn ...

(part of Moldova

Moldova, officially the Republic of Moldova, is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe, with an area of and population of 2.42 million. Moldova is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. ...

); Abkhazia

Abkhazia, officially the Republic of Abkhazia, is a List of states with limited recognition, partially recognised state in the South Caucasus, on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, at the intersection of Eastern Europe and West Asia. It cover ...

and South Ossetia

South Ossetia, officially the Republic of South Ossetia or the State of Alania, is a landlocked country in the South Caucasus with International recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, partial diplomatic recognition. It has an offici ...

(part of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

); and five provinces of Ukraine, which it has illegally annexed. Russia has also established effective political domination over Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

, through the Union State

The Union State is a supranational union consisting of Belarus and Russia, with the stated aim of deepening the relationship between the two states through integration in economic and defence policy. Originally, the Union State aimed to crea ...

. Historian Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the history of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust. He is on leave from his position as the Richard C. Levin, Richar ...

defines Russia's war against Ukraine as "a colonial war, in the sense that Russia meant to conquer, dominate, displace and exploit" the country and its people. Russia has been accused of colonialism in Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

, which it annexed in 2014, by enforced Russification

Russification (), Russianisation or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians adopt Russian culture and Russian language either voluntarily or as a result of a deliberate state policy.

Russification was at times ...

, passportization, and by settling Russian citizens on the peninsula and forcing out Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

.

The

The Wagner Group

The Wagner Group (), officially known as PMC Wagner (, ), is a Russian state-funded private military company (PMC) controlled 2023 Wagner Group plane crash, until 2023 by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a former close ally of Russia's president Vladimir Pu ...

, a Russian state-funded private military company (PMC), has provided military support, security and protection for several autocratic regimes in Africa since 2017. In return, Russian and Wagner-linked companies have been given privileged access to those countries' natural resources, such as rights to gold and diamond mines, while the Russian military has been given access to strategic locations such as airbases and ports. This has been described as a neo-colonial and neo-imperialist kind of state capture

State capture is a type of systemic political corruption in which private interests significantly influence a state's decision-making processes to their own advantage.

The term was first used by the World Bank in 2000 to describe certain Central ...

, whereby Russia gains sway over countries by helping to keep the ruling regime in power and making them reliant on its protection, while generating economic and political benefits for Russia, without benefitting the local population. Russia has also gained geopolitical influence in Africa through election interference and spreading pro-Russian propaganda and anti-Western disinformation. Russian PMCs have been active in the Central African Republic, Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

, Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

, Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa, bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Ivory Coast to the southwest. It covers an area of 274,223 km2 (105,87 ...

, Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

and Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

, among other countries. They have been accused of human rights abuses and killing civilians. In 2024, the Wagner Group in Africa was merged into a new 'Africa Corps' under the direct control of Russia's Ministry of Defense. Analysts for the Russian government have privately acknowledged the neo-colonial nature of Russia's policy towards Africa.

The " Russian world" is a term used by the Russian government and Russian nationalists for territories and communities with a historical, cultural, or spiritual tie to Russia. The Kremlin meanwhile refers to the Russian diaspora

The Russian diaspora is the global community of Ethnicity, ethnic Russians. The Russian-speaking (''Russophone'') diaspora are the people for whom Russian language is the First language, native language, regardless of whether they are ethnic Russ ...

and Russian-speakers in other countries as "Russian compatriots". In her book ''Beyond Crimea: The New Russian Empire'' (2016), Agnia Grigas highlights how ideas like the "Russian world" and "Russian compatriots" have become an "instrument of Russian neo-imperial aims". The Kremlin has sought influence over its "compatriots" by offering them Russian citizenship and passports ( passportization), and in some cases eventually calling for their military protection. Grigas writes that the Kremlin uses the existence of these "compatriots" to "gain influence over and challenge the sovereignty of foreign states and at times even take over territories".

Other countries and entities

Iran

The Iranian government has been called an example of neocolonialism. The motivation for Iran is not economic, but religious. After its establishment in 1979, Iran sought to export Shia Islam globally and position itself as a force in world political structures. Africa's Muslims present a unique opportunity in Iran's dominance in the Muslim world. Iran is able to use these African communities to circumvent economic sanctions and move arms, man power, and nuclear technology. Iran exerts its influence through humanitarian initiatives, such as those seen in Ghana. Through the building of hospitals, schools, and agricultural projects Iran uses "soft power" to assert its influence in Western Africa.Niue

The government of Niue has been trying to get back access to its domain name, .nu. The country signed a deal with a Massachusetts-based non-profit in 1999 that gave away rights to the domain name. Management of the domain name has since shifted to a Swedish organisation. The Niue government is currently fighting on two fronts to get back control on its domain name, including with theICANN

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN ) is a global multistakeholder group and nonprofit organization headquartered in the United States responsible for coordinating the maintenance and procedures of several dat ...

. Toke Talagi

Sir Toke Tufukia Talagi ( ; 9 January 195115 July 2020) was a Niuean politician, diplomat, and statesman. He served as Premier of Niue from 2008 to 2020.

In 1999, he was elected to the Niue Assembly as an Independent. He was elected premier ...

, the long-serving Premier of Niue

The prime minister of Niue (officially the premier of Niue prior to 3 September 2024) is Niue's head of government. They are elected by the Niue Assembly, and form a Cabinet of Niue, Cabinet consisting of themselves and three other members of ...

who died in 2020, called it a form of neocolonialism.

South Korea

To ensure a reliable, long-term supply of food, theSouth Korean government

The government of South Korea () is the national government of the Republic of Korea, created by the Constitution of South Korea as the executive, legislative and judicial authority of the republic. The president acts as the head of state and ...

and powerful Korean multinationals bought farming rights to millions of hectare

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100-metre sides (1 hm2), that is, square metres (), and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. ...

s of agricultural land in under-developed countries.

South Korea's RG Energy Resources Asset Management CEO Park Yong-soo stressed that "the nation does not produce a single drop of crude oil

Petroleum, also known as crude oil or simply oil, is a naturally occurring, yellowish-black liquid chemical mixture found in geological formations, consisting mainly of hydrocarbons. The term ''petroleum'' refers both to naturally occurring u ...

and other key industrial minerals. To power economic growth and support people's livelihoods, we cannot emphasise too much that securing natural resources in foreign countries is a must for our future survival." The head of the Food and Agriculture Organization

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; . (FAO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that leads international efforts to defeat hunger and improve nutrition and food security. Its Latin motto, , translates ...

(FAO), Jacques Diouf, stated that the rise in land deals could create a form of "neocolonialism", with poor states producing food for the rich at the expense of their own hungry people.

In 2008, South Korean multinational Daewoo

Daewoo ( ; ; ; ; literally "great universe" and a portmanteau of "''dae''" meaning great, and the given name of founder and chairman Kim Woo-choong) also known as the Daewoo Group, was a major South Korean chaebol (type of conglomerate) and aut ...

Logistics secured 1.3 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

to grow maize and crops for biofuel

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from Biomass (energy), biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels such as oil. Biofuel can be produced from plants or from agricu ...

s. Roughly half of the country's arable land, as well as rainforests were to be converted into palm

Palm most commonly refers to:

* Palm of the hand, the central region of the front of the hand

* Palm plants, of family Arecaceae

** List of Arecaceae genera

**Palm oil

* Several other plants known as "palm"

Palm or Palms may also refer to:

Music ...

and corn monoculture

In agriculture, monoculture is the practice of growing one crop species in a field at a time. Monocultures increase ease and efficiency in planting, managing, and harvesting crops short-term, often with the help of machinery. However, monocultur ...

s, producing food for export from a country where a third of the population and 50 percent of children under five are malnourished

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

, using South African workers instead of locals. Local residents were not consulted or informed, despite being dependent on the land for food and income. The controversial deal played a major part in prolonged anti-government protests that resulted in over a hundred deaths. This was a source of popular resentment that contributed to the fall of then-President Marc Ravalomanana

Marc Ravalomanana (; born 12 December 1949) is a Malagasy politician who served as the sixth List of presidents of Madagascar, president of Madagascar from 2002 to 2009. Born into a farming Merina people, Merina family in Imerinkasinina, near th ...

. The new president, Andry Rajoelina, cancelled the deal. Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

later announced that South Korea was in talks to develop 100,000 hectares for food production and processing for 700 to 800 billion won. Scheduled to be completed in 2010, it was to be the largest single piece of overseas South Korean agricultural infrastructure ever built.

In 2009, Hyundai Heavy Industries

HD Hyundai Heavy Industries Co., Ltd. (HHI; ) is the world's largest shipbuilding company and a major heavy equipment manufacturer. Its headquarters are in Ulsan, South Korea.

History

HHI was founded in 1972 by Chung Ju-yung as a division ...

acquired a majority stake in a company cultivating 10,000 hectares of farmland in the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East ( rus, Дальний Восток России, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in North Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asia, Asian continent, and is coextensive with the Far Easte ...

and a South Korean provincial government secured 95,000 hectares of farmland in Oriental Mindoro

Oriental Mindoro (), officially the Province of Oriental Mindoro (), is a province in the Philippines located on the island of Mindoro under Mimaropa region in Luzon, about southwest of Manila. The province is bordered by the Verde Island P ...

, central Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, to grow corn

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout Poaceae, grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago ...

. The South Jeolla

South Jeolla Province (), formerly South Chŏlla Province, also known as Jeonnam (), is a province in the Honam region, South Korea, and the southernmost province in mainland Korea. South Jeolla borders the provinces of North Jeolla to the nor ...

province became the first provincial government to benefit from a new central government fund to develop farmland overseas, receiving a loan of $1.9 million. The project was expected to produce 10,000 tonnes of feed in the first year. South Korean multinationals and provincial governments purchased land in Sulawesi

Sulawesi ( ), also known as Celebes ( ), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the List of islands by area, world's 11th-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Min ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

and Bulgan, Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

. The national South Korean government

The government of South Korea () is the national government of the Republic of Korea, created by the Constitution of South Korea as the executive, legislative and judicial authority of the republic. The president acts as the head of state and ...

announced its intention to invest 30 billion won in land in Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

and Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

. As of 2009 discussions with Laos

Laos, officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR), is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Myanmar and China to the northwest, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the southeast, and Thailand to the west and ...

, Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

and Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

were underway.

Cultural approaches

Although the concept of neocolonialism was originally developed within aMarxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

theoretical framework and is generally employed by the political left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* ''Left'' (Helmet album), 2023

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relativ ...

, the term "neocolonialism" is found in other theoretical frameworks.

Coloniality

" Coloniality" claims that knowledge production is strongly influenced by the context of the person producing the knowledge and that this has further disadvantaged developing countries with limited knowledge production infrastructure. It originated among critics of subaltern theories, which, although strongly de-colonial, are less concerned with the source of knowledge.Cultural theory

cultural colonialism

Cultural imperialism (also cultural colonialism) comprises the cultural dimensions of imperialism. The word "imperialism" describes practices in which a country engages culture (language, tradition, ritual, politics, economics) to create and mai ...

'', the desire of wealthy nations to control other nations' values and perceptions through cultural means such as media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

, language, education and religion, ultimately for economic reasons. One impact of this is "colonial mentality

A colonial mentality is the internalized attitude of ethnic or cultural inferiority felt by people as a result of colonization, i.e. them being colonized by another group.Nunning, Vera. (06/01/2015). Fictions of Empire and the (un-making of imper ...

", feelings of inferiority that lead post-colonial societies to latch onto physical and cultural differences between the foreigners and themselves. Foreign ways become held in higher esteem than indigenous ways. Given that colonists and colonisers were generally of different races, the colonised may over time hold that the colonisers' race was responsible for their superiority. Rejections of the colonisers culture, such as the Negritude movement, have been employed to overcome these associations. Post-colonial importation or continuation of cultural mores or elements may be regarded as a form of neocolonialism.

Postcolonialism

Post-colonialism theories in philosophy, political science,literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

and film deal with the cultural legacy of colonial rule. Post-colonialism studies examine how once-colonised writers articulate their national identity; how knowledge about the colonised was generated and applied in service to the interests of the coloniser; and how colonialist literature justified colonialism by presenting the colonised people as inferior whose society, culture and economy must be managed for them. Post-colonial studies incorporate subaltern studies of " history from below"; post-colonial cultural evolution; the psychopathology

Psychopathology is the study of mental illness. It includes the signs and symptoms of all mental disorders. The field includes Abnormal psychology, abnormal cognition, maladaptive behavior, and experiences which differ according to social norms ...

of colonisation (by Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

); and the cinema of film makers such as the Cuban Third Cinema

Third Cinema () is a Latin American film movement formed in the 1960s which critiques neocolonialism, the capitalist system, and the Hollywood model of cinema as mere entertainment to make money. The term was coined in the manifesto ''Hacia un te ...

, e.g. Tomás Gutiérrez Alea

Tomás Gutiérrez- Alea (; December 11, 1928 – April 16, 1996) was a Cuban film director and screenwriter. Gutiérrez Alea wrote and directed more than twenty features, documentaries, and short films, which are known for his sharp insight i ...

, and Kidlat Tahimik.

Critical theory

Critiques of postcolonialism/neocolonialism are evident inliterary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, m ...

. International relations theory

International relations theory is the study of international relations (IR) from a theoretical perspective. It seeks to explain behaviors and outcomes in international politics. The three most prominent School of thought, schools of thought are ...

defined "postcolonialism" as a field of study. While the lasting effects of cultural colonialism are of central interest, the intellectual antecedents in cultural critiques of neocolonialism are economic. Critical international relations theory references neocolonialism from Marxist positions as well as postpositivist

Postpositivism or postempiricism is a metatheoretical stance that critiques and amends positivism and has impacted theories and practices across philosophy, social sciences, and various models of scientific inquiry. While positivists emphasize ...

positions, including postmodernist

Postmodernism encompasses a variety of artistic, Culture, cultural, and philosophical movements that claim to mark a break from modernism. They have in common the conviction that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of depicting ...

, postcolonial

Postcolonialism (also post-colonial theory) is the critical academic study of the cultural, political and economic consequences of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on the impact of human control and extractivism, exploitation of colonized pe ...

and feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

approaches. These differ from both realism and liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

in their epistemological

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowled ...

and ontological

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of reality and every ...

premises. The neoliberalist approach tends to depict modern forms of colonialism as a benevolent imperialism.

Neocolonialism and gender construction

Concepts of neocolonialism can be found in theoretical works investigating gender outside the global north. Often these conceptions can be seen as erasing gender norms within communities in the global south to create conceptions of gender that align with the global north. Gerise Herndon argues that applying feminism or other theoretical frameworks around gender must look at the relationship between the individual subject, their home country or culture, and the country and culture that exerts neocolonial control over the country. In her piece "Gender Construction and Neocolonialism", Herndon presents the writings ofMaryse Condé

Maryse Condé (née Marise Liliane Appoline Boucolon; 11 February 1934 – 2 April 2024) was a French novelist, critic, and playwright from the French Overseas department and region of Guadeloupe. She was also an academic, whose teaching car ...

as an example of grappling with what it means to have your identity constructed by neocolonial powers. Her work explores how women in burgeoning nations rebuilt their identities in the postcolonial period. The task of creating new identities was met with challenges from not only an internal view of what the culture was in these places but also from the external expectations of ex-colonial powers.

An example of the construction of gender norms and conceptions by neocolonial interests is made clear in the Ugandan Anti-Homosexuality Act introduced in 2009 and passed in 2014. The act expanded upon previously existing laws against sodomy to make gay relationships punishable by life imprisonment. The call for this bill came from Ugandans who claimed traditional African values that did not include homosexuality. This act faced backlash from western countries, citing human rights violations. The United States imposed economic sanctions

Economic sanctions or embargoes are Commerce, commercial and Finance, financial penalties applied by states or institutions against states, groups, or individuals. Economic sanctions are a form of Coercion (international relations), coercion tha ...

against Uganda in June 2014 in response to the law, the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

indefinitely postponed a $90 million aid loan to Uganda and the governments of Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

halted aid to Uganda in opposition to the law; the Ugandan government defended the bill and rejected condemnation of it, with the country's authorities stating President Museveni wanted "to demonstrate Uganda's independence in the face of Western pressure and provocation". The Ugandan response was to claim that this was a neocolonialist attack on their culture. Kristen Cheney argued that this is a misrepresentation of neocolonialism at work and that this conception of gender and anti-homosexuality erased historically diverse gender identities in Africa. To Cheney, neocolonialism was found in accepting conservative gender identity politics, specifically those of U.S.-based Evangelical Christians. Before the introduction of this act, conservative Christian groups in the United States had put African religious leaders and politicians on their payroll, reflecting the talking points of U.S.-based Christian evangelism. Cheney argues that this adoption and bankrolling of U.S. conservative Christian evangelist thought in Uganda is the real neocolonialism and effectively erodes any historical gender diversity in Africa.

See also

References

Bibliography

* *Further reading

* * * * *Mongo Beti

Alexandre Biyidi Awala (30 June 1932 – 8 October 2001), known as Mongo Beti or Eza Boto, was a Cameroonian author and polemicist. Beti has been called one of the most perceptive French-African writers in his presentations of African life.

...

,'' Main basse sur le Cameroun. Autopsie d'une décolonisation'' (1972), new edition La Découverte, Paris 2003 classical critique of neo-colonialism. Raymond Marcellin, the French Minister of the Interior at the time, tried to prohibit the book. It could only be published after fierce legal battles.* Frédéric Turpin. ''De Gaulle, Pompidou et l'Afrique (1958–1974): décoloniser et coopérer'' (Les Indes savantes, Paris, 2010. rounded on Foccart's previously inaccessibles archives* Kum-Kum Bhavnani. (ed., et al.) ''Feminist futures: Re-imagining women, culture and development'' (Zed Books

Zed Books is a non-fiction publishing company based in London, UK. It was founded in 1977 under the name Zed Press by Roger van Zwanenberg.

Zed publishes books for an international audience of both general and academic readers, covering areas ...

, NY, 2003). See: Ming-yan Lai's "Of Rural Mothers, Urban Whores and Working Daughters: Women and the Critique of Neocolonial Development in Taiwan's Nativist Literature", pp. 209–225.

* David Birmingham. ''The decolonisation of Africa'' (Ohio University Press

Ohio University Press (OUP) is a university press associated with Ohio University. Founded in 1947, it is the oldest and largest scholarly press in the state of Ohio. Ohio University Press is also a member of the Association of University Presses ...

, 1995).

* Charles Cantalupo(ed.). ''The world of Ngugi wa Thiong'o'' (Africa World Press, 1995).

* Laura Chrisman and Benita Parry (ed.) ''Postcolonial theory and criticism'' (English Association, Cambridge, 2000).

* Renato Constantino

Renato Reyes Constantino Sr. (March 10, 1919 – September 15, 1999) was a Filipino historian known for being part of the leftist tradition of Philippine historiography. Apart from being a historian, Constantino was also engaged in foreign se ...

. ''Neocolonial identity and counter-consciousness: Essays on cultural decolonisation'' ( Merlin Press, London, 1978).

* George A. W. Conway. ''A responsible complicity: Neo/colonial power-knowledge and the work of Foucault, Said, Spivak'' ( University of Western Ontario Press, 1996).

* Julia V. Emberley. ''Thresholds of difference: feminist critique, native women's writings, postcolonial theory'' (University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university calendar. Its first s ...

, 1993).

* Nikolai Aleksandrovich Ermolov. ''Trojan horse of neo-colonialism: U.S. policy of training specialists for developing countries'' (Progress Publishers

Progress Publishers was a Moscow-based Soviet Union, Soviet publisher founded in 1931.

Publishing program

Progress Publishers published books in a variety of languages: Russian, English, and many other European and Asian languages. They issued ma ...

, Moscow, 1966).

* Thomas Gladwin. ''Slaves of the white myth: The psychology of neo-colonialism'' ( Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 1980).

* Lewis Gordon

Lewis Ricardo Gordon (born May 12, 1962) is an American philosopher at the University of Connecticut who works in the areas of Africana philosophy, existentialism, phenomenology, social and political theory, postcolonial thought, theories of r ...

. Her Majesty's Other Children: Sketches of Racism from a Neocolonial Age (Rowman & Littlefield

Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group is an American independent academic publishing company founded in 1949. Under several imprints, the company offers scholarly books for the academic market, as well as trade books. The company also owns ...

, 1997).

* Ankie M. M. Hoogvelt. ''Globalisation and the postcolonial world: The new political economy of development'' (Johns Hopkins University Press

Johns Hopkins University Press (also referred to as JHU Press or JHUP) is the publishing division of Johns Hopkins University. It was founded in 1878 and is the oldest continuously running university press in the United States. The press publi ...

, 2001).

* J. M. Hobson, ''The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation'' (Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, 2004).

* M. B. Hooker. ''Legal pluralism; an introduction to colonial and neo-colonial laws'' (Clarendon Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, Oxford, 1975).

* E.M. Kramer (ed.) ''The emerging monoculture: assimilation and the "model minority"'' (Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2003). See: Archana J. Bhatt's "Asian Indians and the Model Minority Narrative: A Neocolonial System", pp. 203–221.

* Geir Lundestad

Geir Lundestad (17 January 1945 – 22 September 2023) was a Norwegian historian, who until 2014 served as the director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute when Olav Njølstad took over. In this capacity, he also served as the secretary of the Nor ...

(ed.) ''The fall of great powers: Peace, stability, and legitimacy'' ( Scandinavian University Press, Oslo, 1994).

* Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

. 'Colonialism and neo-colonialism. Translated by Steve Brewer, Azzedine Haddour, Terry McWilliams Republished in the 2001 edition by Routledge France. .

* Peccia, T., 2014, "The Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks: A New Sphere of Influence 2.0", Jura Gentium – Rivista di Filosofia del Diritto Internazionale e della Politica Globale, Sezione "L'Afghanistan Contemporaneo"The Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks

* Stuart J. Seborer. ''U.S. neo-colonialism in Africa'' (

International Publishers

International Publishers is a book publishing company based in New York City, specializing in Marxism, Marxist works of economics, political science, and history.

Company history

Establishment

International Publishers Company, Inc., was founde ...

, NY, 1974).

* D. Simon. ''Cities, capital and development: African cities in the world economy'' (Halstead, NY, 1992).

* Phillip Singer(ed.) ''Traditional healing, new science or new colonialism": (essays in critique of medical anthropology)'' (Conch Magazine, Owerri, 1977).

* Jean Suret-Canale. ''Essays on African history: From the slave trade to neo-colonialism'' (Hurst, London 1988).

* Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. ''Barrel of a pen: Resistance to repression in neo-colonial Kenya'' (Africa Research & Publications Project, 1983).

* Carlos Alzugaray Treto. El ocaso de un régimen neocolonial: Estados Unidos y la dictadura de Batista durante 1958,(The twilight of a neocolonial regime: The United States and Batista during 1958), in Temas: Cultura, Ideología y Sociedad, No.16-17, October 1998/March 1999, pp. 29–41 (La Habana: Ministry of Culture).

* Uzoigw, Godfrey N. "Neocolonialism Is Dead: Long Live Neocolonialism." '' Journal of Global South Studies'' 36.1 (2019): 59–87.

*

* Richard Werbner (ed.) ''Postcolonial identities in Africa'' (Zed Books, NJ, 1996).

External links

Mbeki warns on China-Africa ties

*

''Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism'', by Kwame Nkrumah, originally published 1965

at Marxists Internet Archive.

"Africa 'should not pay its debts – BBC

July 6, 2004.

Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs video (ram) – hosted by Columbia Univ.

by Gloria Emeagwali.

Academic course materials

: Joseph Hill,

University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

, 2008.Studying African development history: Study guides

Lauri Siitonen, Päivi Hasu, Wolfgang Zeller.

Helsinki University