Neo-gothic architecture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half of the 19th century, mostly in England. Increasingly serious and learned admirers sought to revive medieval

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half of the 19th century, mostly in England. Increasingly serious and learned admirers sought to revive medieval

Throughout France in the 16th and 17th centuries, churches continued to be built following Gothic principles (structure of the buildings, application of tracery) such as St-Eustache (1532–1640, façade 1754) in Paris and Orléans Cathedral (1601–1829). This newer construction incorporated some little changes like the use of round arches instead of pointed arches and the application of some Classical details, until largely being replaced in new construction with the arrival of Baroque architecture.

In

Throughout France in the 16th and 17th centuries, churches continued to be built following Gothic principles (structure of the buildings, application of tracery) such as St-Eustache (1532–1640, façade 1754) in Paris and Orléans Cathedral (1601–1829). This newer construction incorporated some little changes like the use of round arches instead of pointed arches and the application of some Classical details, until largely being replaced in new construction with the arrival of Baroque architecture.

In

The revived Gothic style was not limited to architecture. Classical Gothic buildings of the 12th to 16th Centuries were a source of inspiration to 19th-century designers in numerous fields of work. Architectural elements such as pointed arches, steep-sloping roofs and fancy carvings like lace and lattice work were applied to a wide range of Gothic Revival objects. Some examples of Gothic Revival influence can be found in heraldic motifs in coats of arms, furniture with elaborate painted scenes like the whimsical Gothic detailing in English furniture is traceable as far back as Lady Pomfret's house in Arlington Street, London (1740s), and Gothic fretwork in chairbacks and glazing patterns of bookcases is a familiar feature of Chippendale's ''Director'' (1754, 1762), where, for example, the three-part bookcase employs Gothic details with Rococo profusion, on a symmetrical form. Abbotsford in the

The revived Gothic style was not limited to architecture. Classical Gothic buildings of the 12th to 16th Centuries were a source of inspiration to 19th-century designers in numerous fields of work. Architectural elements such as pointed arches, steep-sloping roofs and fancy carvings like lace and lattice work were applied to a wide range of Gothic Revival objects. Some examples of Gothic Revival influence can be found in heraldic motifs in coats of arms, furniture with elaborate painted scenes like the whimsical Gothic detailing in English furniture is traceable as far back as Lady Pomfret's house in Arlington Street, London (1740s), and Gothic fretwork in chairbacks and glazing patterns of bookcases is a familiar feature of Chippendale's ''Director'' (1754, 1762), where, for example, the three-part bookcase employs Gothic details with Rococo profusion, on a symmetrical form. Abbotsford in the

French neo-Gothic had its roots in the French medieval Gothic architecture, where it was created in the 12th century. Gothic architecture was sometimes known during the medieval period as the "Opus Francigenum", (the "French Art"). French scholar Alexandre de Laborde wrote in 1816 that "Gothic architecture has beauties of its own", which marked the beginning of the Gothic Revival in France. Starting in 1828, Alexandre Brogniart, the director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, produced fired enamel paintings on large panes of plate glass, for King Louis-Philippe's

French neo-Gothic had its roots in the French medieval Gothic architecture, where it was created in the 12th century. Gothic architecture was sometimes known during the medieval period as the "Opus Francigenum", (the "French Art"). French scholar Alexandre de Laborde wrote in 1816 that "Gothic architecture has beauties of its own", which marked the beginning of the Gothic Revival in France. Starting in 1828, Alexandre Brogniart, the director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, produced fired enamel paintings on large panes of plate glass, for King Louis-Philippe's  The French Gothic Revival was set on more sound intellectual footings by a pioneer, Arcisse de Caumont, who founded the Societé des Antiquaires de Normandie at a time when ''antiquaire'' still meant a connoisseur of antiquities, and who published his great work on architecture in French Normandy in 1830. The following year

The French Gothic Revival was set on more sound intellectual footings by a pioneer, Arcisse de Caumont, who founded the Societé des Antiquaires de Normandie at a time when ''antiquaire'' still meant a connoisseur of antiquities, and who published his great work on architecture in French Normandy in 1830. The following year  In Belgium, a 15th-century church in

In Belgium, a 15th-century church in

France had lagged slightly in entering the neo-Gothic scene, but produced a major figure in the revival in

France had lagged slightly in entering the neo-Gothic scene, but produced a major figure in the revival in  The arguments against modern construction materials began to collapse in the mid-19th century as great prefabricated structures such as the glass and iron Crystal Palace and the glazed courtyard of the

The arguments against modern construction materials began to collapse in the mid-19th century as great prefabricated structures such as the glass and iron Crystal Palace and the glazed courtyard of the

In the United States, Collegiate Gothic was a late and literal resurgence of the English Gothic Revival, adapted for American college and university campuses. The term "Collegiate Gothic" originated from American architect

In the United States, Collegiate Gothic was a late and literal resurgence of the English Gothic Revival, adapted for American college and university campuses. The term "Collegiate Gothic" originated from American architect

The Gothic style dictated the use of structural members in

The Gothic style dictated the use of structural members in

File:Parliament of Hungary November 2017.jpg,

File:Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate.jpg,

File:Basilica de Nuestra Senora de Lujan.jpg, Basilica of Our Lady of Luján,

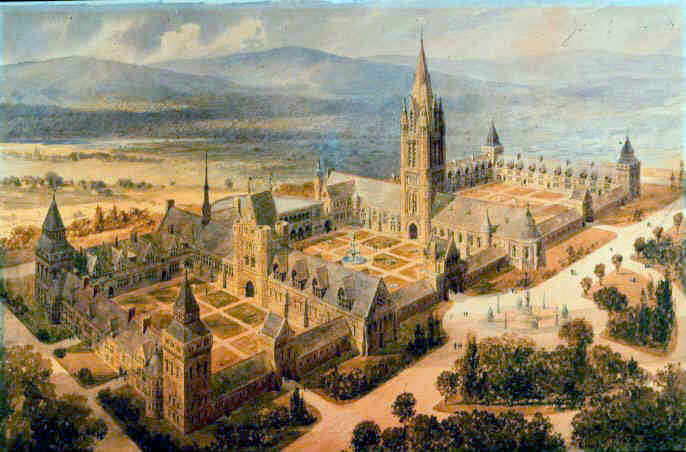

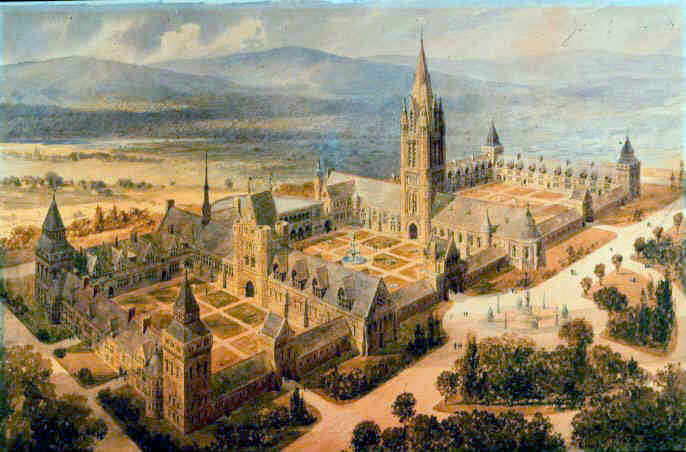

File:SydneyUniversity_MainBuilding_Panorama.jpg, University of Sydney Quadrangle, Sydney, Australia: 1854–1862

File:St_Patrick's_Cathedral_-_Gothic_Revival_Style.jpg, St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, Australia: 1858–1939

File:Christ ChurchCathedral1 gobeirne.jpg, ChristChurch Cathedral, New Zealand: 1864–1904

File:Auckland High Court Building - 4523179010.jpg,

File:Church of Saviour in Baku.jpg, Church of the Saviour,

File:Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory - Cup and Saucer - 1998.412 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif, Cup and saucer, produced by the Sèvres porcelain factory and decorated by Pierre Huard, 1827, porcelain,

Basilique Sainte-Clotilde, Paris

(archived copy)

Canada by Design: Parliament Hill, Ottawa

at Library and Archives Canada (archived copy)

(archived copy)

Proyecto Documenta's entries for neo-Gothic elements at the Valparaíso's churches

(archived copy) {{DEFAULTSORT:Gothic Revival Architecture American architectural styles Architectural styles British architectural styles Revival architectural styles Victorian architectural styles

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half of the 19th century, mostly in England. Increasingly serious and learned admirers sought to revive medieval

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half of the 19th century, mostly in England. Increasingly serious and learned admirers sought to revive medieval Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High Middle Ages, High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It evolved f ...

, intending to complement or even supersede the neoclassical styles prevalent at the time. Gothic Revival draws upon features of medieval examples, including decorative patterns, finial

A finial () or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the Apex (geometry), apex of a dome, spire, tower, roo ...

s, lancet window

A lancet window is a tall, narrow window with a sharp pointed arch at its top. This arch may or may not be a steep lancet arch (in which the compass centres for drawing the arch fall outside the opening). It acquired the "lancet" name from its rese ...

s, and hood mould

In architecture, a hood mould, hood, label mould (from Latin , lip), drip mould or dripstone is an external moulded projection from a wall over an opening to throw off rainwater, historically often in form of a '' pediment''. This moulding can be ...

s. By the middle of the 19th century, Gothic Revival had become the pre-eminent architectural style in the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

, only to begin to fall out of fashion in the 1880s and early 1890s.

For some in England, the Gothic Revival movement had roots that were intertwined with philosophical movements associated with Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and a re-awakening of high church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

or Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholicism, Catholic heritage (especially pre-English Reformation, Reformation roots) and identity of the Church of England and various churches within Anglicanism. Anglo-Ca ...

belief concerned by the growth of religious nonconformism. The "Anglo-Catholic" tradition of religious belief and style became known for its intrinsic appeal in the third quarter of the 19th century. Gothic Revival architecture varied considerably in its faithfulness to both the ornamental styles and construction principles of its medieval ideal, sometimes amounting to little more than pointed window frames and touches of neo-Gothic decoration on buildings otherwise created on wholly 19th-century plans, using contemporary materials and construction methods; most notably, this involved the use of iron and, after the 1880s, steel in ways never seen in medieval exemplars.

In parallel with the ascendancy of neo-Gothic styles in 19th century England, interest spread to the rest of Europe, Australia, Asia and the Americas; the 19th and early 20th centuries saw the construction of very large numbers of Gothic Revival structures worldwide. The influence of Revivalism had nevertheless peaked by the 1870s. New architectural movements, sometimes related, as in the Arts and Crafts movement

The Arts and Crafts movement was an international trend in the decorative and fine arts that developed earliest and most fully in the British Isles and subsequently spread across the British Empire and to the rest of Europe and America.

Initiat ...

, and sometimes in outright opposition, such as Modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

, gained ground, and by the 1930s the architecture of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

was generally condemned or ignored. The later 20th century saw a revival of interest, manifested in the United Kingdom by the establishment of the Victorian Society

The Victorian Society is a UK charity and amenity society that campaigns to preserve and promote interest in Victorian and Edwardian architecture and heritage built between 1837 and 1914 in England and Wales. As a statutory consultee, by l ...

in 1958.

Roots

The rise ofevangelicalism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw in England a reaction in the high church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

movement which sought to emphasise the continuity between the established church and the pre-Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

Catholic church. Architecture, in the form of the Gothic Revival, became one of the main weapons in the high church's armoury. The Gothic Revival was also paralleled and supported by "medievalism

Medievalism is a system of belief and practice inspired by the Middle Ages of Europe, or by devotion to elements of that period, which have been expressed in areas such as architecture, literature, music, art, philosophy, scholarship, and variou ...

", which had its roots in antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

concerns with survivals and curiosities. As "industrialisation

Industrialisation ( UK) or industrialization ( US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for th ...

" progressed, a reaction against machine production and the appearance of factories also grew. Proponents of the picturesque such as Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

and Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 1812 – 14 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival architecture ...

took a critical view of industrial society and portrayed pre-industrial medieval society as a golden age. To Pugin, Gothic architecture was infused with the Christian values that had been supplanted by classicism

Classicism, in the arts, refers generally to a high regard for a classical period, classical antiquity in the Western tradition, as setting standards for taste which the classicists seek to emulate. In its purest form, classicism is an aesthe ...

and were being destroyed by industrialisation

Industrialisation ( UK) or industrialization ( US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for th ...

.

Gothic Revival also took on political connotations, with the "rational" and "radical" Neoclassical style being seen as associated with republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

and liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

(as evidenced by its use in the United States and to a lesser extent in Republican France). In contrast, the more spiritual and traditional Gothic Revival became associated with monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

and conservatism

Conservatism is a Philosophy of culture, cultural, Social philosophy, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, Convention (norm), customs, and Value (ethics and social science ...

, which was reflected by the choice of styles for the rebuilt government centres of the British Parliament's Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster is the meeting place of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is located in London, England. It is commonly called the Houses of Parliament after the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two legislative ch ...

in London, the Canadian Parliament Buildings in Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

and the Hungarian Parliament Building

The Hungarian Parliament Building ( , ), also known as the Parliament of Budapest after its location, is the seat of the National Assembly of Hungary, a notable landmark of Hungary, and a popular tourist destination in Budapest. It is situated o ...

in Budapest.

In English literature, the architectural Gothic Revival and classical Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

gave rise to the Gothic novel

Gothic fiction, sometimes referred to as Gothic horror (primarily in the 20th century), is a literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name of the genre is derived from the Renaissance era use of the word "gothic", as a pejorative to mean ...

genre, beginning with ''The Castle of Otranto

''The Castle of Otranto'' is a novel by Horace Walpole. First published in 1764, it is generally regarded as the first Gothic novel. In the second edition, Walpole applied the word 'Gothic' to the novel in the subtitle – ''A Gothic Story''. Se ...

'' (1764) by Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (; 24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English Whig politician, writer, historian and antiquarian.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twickenham, southwest London ...

, and inspired a 19th-century genre of medieval poetry that stems from the pseudo- bardic poetry of "Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora (poem), Temora'' (1763), and later c ...

". Poems such as "Idylls of the King

''Idylls of the King'', published between 1859 and 1885, is a cycle of twelve narrative poems by the English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892; Poet Laureate from 1850) which retells the legend of King Arthur, his knights, his love f ...

" by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (; 6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of ...

recast specifically modern themes in medieval settings of Arthurian

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a leader of the post-Ro ...

romance. In German literature

German literature () comprises those literature, literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy ...

, the Gothic Revival also had a grounding in literary fashions.

Survival and revival

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High Middle Ages, High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It evolved f ...

began at the Basilica of Saint Denis near Paris, and the Cathedral of Sens in 1140 and ended with a last flourish in the early 16th century with buildings like Henry VII's Chapel at Westminster. However, Gothic architecture did not die out completely in the 16th century but instead lingered in on-going cathedral-building projects; at Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

Universities, and in the construction of churches in increasingly isolated rural districts of England, France, Germany, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and in Spain.

Britain and Ireland

St Columb's Cathedral

St Columb's Cathedral in the walled city of Derry, Northern Ireland, is the cathedral church and episcopal see of the Church of Ireland's Diocese of Derry and Raphoe. It is also the parish church of Templemore. It is dedicated to Saint Columba ...

, in Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry, is the second-largest City status in the United Kingdom, city in Northern Ireland, and the fifth-largest on the island of Ireland. Located in County Londonderry, the city now covers both banks of the River Fo ...

, may be considered 'Gothic Survival', as it was completed in 1633 in a Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-ce ...

style. Similarly, Gothic architecture survived in some urban settings during the later 17th century, as shown in Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, where some additions and repairs to Gothic buildings were considered to be more in keeping with the style of the original structures than contemporary Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

.

In contrast, Dromore Cathedral

Dromore Cathedral, formally The Cathedral Church of Christ the Redeemer, Dromore, is one of two cathedral churches (the other is Down Cathedral) in the Diocese of Down and Dromore of the Church of Ireland (Anglican / Episcopal). It is situated ...

, built in 1660/1661, immediately after the end of the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, was the English form of government lasting from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659, under which the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotl ...

, revived Early English forms, demonstrating the restitution of the monarchy and claiming Ireland for the English crown. At the same time, the Great Hall of Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament of the United King ...

, that had been despoiled by the Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

, was rebuilt in a mixture of Baroque and older Gothic forms, demonstrating the restitution of the Anglican Church. These two buildings can be said to herald the onset of Gothic Revival architecture, several decades before it became mainstream. Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was acc ...

's Tom Tower for Christ Church, University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, consciously set out to imitate Cardinal Wolsey's architectural style. Writing to Dean Fell in 1681, he noted; "I resolved it ought to be Gothic to agree with the Founder's work", adding that to do otherwise would lead to "an unhandsome medley". Pevsner suggests that he succeeded "to the extent that innocent visitors never notice the difference". It was followed in 1697–1704 by the rebuilding of Collegiate Church of St Mary

The Collegiate Church of St Mary is a Church of England parish church in Warwick, Warwickshire, England. It is in the centre of the town just east of the market place. It is Grade I listed, and a member of the Major Churches Network.

The church ...

in Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

as a stone-vaulted hall church

A hall church is a Church (building), church with a nave and aisles of approximately equal height. In England, Flanders and the Netherlands, it is covered by parallel roofs, typically, one for each vessel, whereas in Germany there is often one s ...

, whereas the burnt church had been a basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica (Greek Basiliké) was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek Eas ...

with timbered roofs. Also in Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It is bordered by Staffordshire and Leicestershire to the north, Northamptonshire to the east, Ox ...

, in 1729/30, the nave and aisles of the church of St Nicholas at Alcester

Alcester ( ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon District in Warwickshire, England. It is west of Stratford-upon-Avon, and 7 miles south of Redditch. The town dates back to the times of Roman ...

were rebuilt by Edward and Thomas Woodward, the exterior in Gothic forms but with a Neoclassical interior. At the same time, 1722–1746, Nicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor ( – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principal architects ...

added the west towers to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, which made him a pioneer of Gothic Revival completions of medieval buildings, which from the late 19th century were increasingly disapproved of, although work in this style continued into the 20th century. Back in Oxford, the redecoration of the dining hall at University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies f ...

between 1766 and 1768 has been described as "the first major example of the Gothic Revival style in Oxford".

Continental Europe

Throughout France in the 16th and 17th centuries, churches continued to be built following Gothic principles (structure of the buildings, application of tracery) such as St-Eustache (1532–1640, façade 1754) in Paris and Orléans Cathedral (1601–1829). This newer construction incorporated some little changes like the use of round arches instead of pointed arches and the application of some Classical details, until largely being replaced in new construction with the arrival of Baroque architecture.

In

Throughout France in the 16th and 17th centuries, churches continued to be built following Gothic principles (structure of the buildings, application of tracery) such as St-Eustache (1532–1640, façade 1754) in Paris and Orléans Cathedral (1601–1829). This newer construction incorporated some little changes like the use of round arches instead of pointed arches and the application of some Classical details, until largely being replaced in new construction with the arrival of Baroque architecture.

In Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, in 1646, the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

architect Carlo Rainaldi

Carlo Rainaldi (4 May 1611 – 8 February 1691) was an Italian architect of the Baroque period.

Biography

Born in Rome, Rainaldi was one of the leading architects of 17th-century Rome, known for a certain grandeur in his designs. He worked at f ...

constructed Gothic vaults (completed 1658) for the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, which had been under construction since 1390; there, the Gothic context of the structure overrode considerations of the current architectural mode. Similarly, in St. Salvator's Cathedral of Bruges

Bruges ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the province of West Flanders, in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is in the northwest of the country, and is the sixth most populous city in the country.

The area of the whole city amoun ...

, the timbered medieval vaults of nave and choir were replaced by "Gothic" stone vaults in 1635 resp. 1738/39. Guarino Guarini

Camillo Guarino Guarini (17 January 16246 March 1683) was an Italian architect of the Piedmontese Baroque architecture, Baroque, active in Turin as well as Sicily, Kingdom of France, France and Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal. He was a Theatines, ...

, a 17th-century Theatine monk active primarily in Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, recognized the "Gothic order" as one of the primary systems of architecture and made use of it in his practice.

Even in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

of the late 17th and 18th centuries, where Baroque dominated, some architects continued to use elements of the Gothic style. The most important example is Johann Santini Aichel, whose Pilgrimage Church of Saint John of Nepomuk in Žďár nad Sázavou

Žďár nad Sázavou (; ) is a town in the Vysočina Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 20,000 inhabitants. The town is an industrial and tourist centre. It is known for the Pilgrimage Church of Saint John of Nepomuk, which is a UNESCO Wor ...

, Czech Republic, represents a peculiar and creative synthesis of Baroque and Gothic. An example of another and less striking use of the Gothic style in the time is the Basilica of Our Lady of Hungary

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica (Greek Basiliké) was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East ...

in Márianosztra, Hungary, whose choir (adjacent to a Baroque nave) was long considered authentically Gothic, because the 18th-century architect used medieval shapes to emphasize the continuity of the monastic community with its 14th-century founders.

Romantic challenges

During the mid-18th century rise ofRomanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, an increased interest and awareness of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

among influential connoisseurs created a more appreciative approach to selected medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

arts, beginning with church architecture, the tomb monuments of royal and noble personages, stained glass, and late Gothic illuminated manuscripts. Other Gothic arts, such as tapestries and metalwork, continued to be disregarded as barbaric and crude, however sentimental and nationalist associations with historical figures were as strong in this early revival as purely aesthetic concerns.

German Romanticists (including philosopher and writer Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

and architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Karl Friedrich Schinkel (13 March 1781 – 9 October 1841) was a Prussian architect, urban planning, city planner and painter who also designed furniture and stage sets. Schinkel was one of the most prominent architects of Germany and designed b ...

), began to appreciate the picturesque

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in ''Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year ...

character of ruins—"picturesque" becoming a new aesthetic quality—and those mellowing effects of time that the Japanese call '' wabi-sabi'' and that Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (; 24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English Whig politician, writer, historian and antiquarian.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twickenham, southwest London ...

independently admired, mildly tongue-in-cheek, as "the true rust of the Barons' wars". The "Gothick" details of Walpole's Twickenham villa, Strawberry Hill House

Strawberry Hill House—often called simply Strawberry Hill—is a Gothic Revival architecture, Gothic Revival villa that was built in Twickenham, London, by Horace Walpole (1717–1797) from 1749 onward. It is a typical example of the "#Strawb ...

begun in 1749, appealed to the rococo

Rococo, less commonly Roccoco ( , ; or ), also known as Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and dramatic style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpte ...

tastes of the time, and were fairly quickly followed by James Talbot at Lacock Abbey

Lacock Abbey in the village of Lacock, Wiltshire, England, was founded in the early 13th century by Ela, Countess of Salisbury, as a nunnery of the Augustinian order. The abbey remained a nunnery until the Dissolution of the monasteries in ...

, Wiltshire. By the 1770s, thoroughly neoclassical architects such as Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (architect), William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and train ...

and James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the Neoclassicism, neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to ...

were prepared to provide Gothic details in drawing-rooms, libraries and chapels and, for William Beckford at Fonthill in Wiltshire, a complete romantic vision of a Gothic abbey.

Some of the earliest architectural examples of the revived are found in Scotland. Inveraray Castle

Inveraray Castle (pronounced or ; Scottish Gaelic ''Caisteal Inbhir Aora'' ) is a country house near Inveraray in the county of Argyll, in western Scotland, on the shore of Loch Fyne, Scotland's longest sea loch. It is one of the earliest ex ...

, constructed from 1746 for the Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll () is a title created in the peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The earls, marquesses, and dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerful noble families in Scotlan ...

, with design input from William Adam, displays the incorporation of turrets. The architectural historian John Gifford writes that the castellations were the "symbolic assertion of the still quasi-feudal power he dukeexercised over the inhabitants within his heritable jurisdictions". Most buildings were still largely in the established Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

style, but some houses incorporated external features of the Scots baronial style. Robert Adam's houses in this style include Mellerstain

Mellerstain House is a Scottish country house around north of Kelso in the Borders, Scotland. It is currently the home of George Baillie-Hamilton, 14th Earl of Haddington, and is designated as a historical monument.

History

The older house ...

and Wedderburn in Berwickshire and Seton Castle in East Lothian, but it is most clearly seen at Culzean Castle, Ayrshire, remodelled by Adam from 1777. The eccentric landscape designer Batty Langley

Batty Langley (''baptised'' 14 September 1696 – 3 March 1751) was an English garden designer, and prolific writer who produced a number of engraved designs for " Gothick" structures, summerhouses and garden seats in the years before the mid-1 ...

even attempted to "improve" Gothic forms by giving them classical proportions.

A younger generation, taking Gothic architecture more seriously, provided the readership for John Britton's series ''Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain'', which began appearing in 1807. In 1817, Thomas Rickman wrote an ''Attempt...'' to name and define the sequence of Gothic styles in English ecclesiastical architecture, "a text-book for the architectural student". Its long antique title is descriptive: ''Attempt to discriminate the styles of English architecture from the Conquest to the Reformation; preceded by a sketch of the Grecian and Roman orders, with notices of nearly five hundred English buildings''. The categories he used were Norman, Early English, Decorated, and Perpendicular

In geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if they intersect at right angles, i.e. at an angle of 90 degrees or π/2 radians. The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the '' perpendicular symbol'', � ...

. It went through numerous editions, was still being republished by 1881, and has been reissued in the 21st century.

The most common use for Gothic Revival architecture was in the building of churches. Major examples of Gothic cathedrals in the U.S. include the cathedrals of St. John the Divine and St. Patrick in New York City and the Washington National Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Episcopal Diocese of Washington, commonly known as Washington National Cathedral or National Cathedral, is a cathedral of the Episcopal Church. The cathedral is located in Wa ...

on Mount St. Alban in northwest Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

One of the biggest churches in Gothic Revival style in Canada is the Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate

Basilica of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception is a Roman Catholic minor basilica and parish church in Guelph, Ontario, Canada. A Gothic Revival style building constructed between 1876 and 1888 by architect Joseph Connolly, it is considered C ...

in Guelph, Ontario

Guelph ( ; 2021 Canadian Census population 143,740) is a city in Southwestern Ontario, Canada. Known as The Royal City, it is roughly east of Kitchener, Ontario, Kitchener and west of Downtown Toronto, at the intersection of Ontario Highway 6, ...

.

Gothic Revival architecture remained one of the most popular and long-lived of the many revival styles of architecture. Although it began to lose force and popularity after the third quarter of the 19th century in commercial, residential and industrial fields, some buildings such as churches, schools, colleges and universities were still constructed in the Gothic style, often known as "Collegiate Gothic", which remained popular in England, Canada and in the United States until well into the early to mid-20th century. Only when new materials, like steel and glass along with concern for function in everyday working life and saving space in the cities, meaning the need to build up instead of out, began to take hold did the Gothic Revival start to disappear from popular building requests.

Gothic Revival in the other decorative arts

The revived Gothic style was not limited to architecture. Classical Gothic buildings of the 12th to 16th Centuries were a source of inspiration to 19th-century designers in numerous fields of work. Architectural elements such as pointed arches, steep-sloping roofs and fancy carvings like lace and lattice work were applied to a wide range of Gothic Revival objects. Some examples of Gothic Revival influence can be found in heraldic motifs in coats of arms, furniture with elaborate painted scenes like the whimsical Gothic detailing in English furniture is traceable as far back as Lady Pomfret's house in Arlington Street, London (1740s), and Gothic fretwork in chairbacks and glazing patterns of bookcases is a familiar feature of Chippendale's ''Director'' (1754, 1762), where, for example, the three-part bookcase employs Gothic details with Rococo profusion, on a symmetrical form. Abbotsford in the

The revived Gothic style was not limited to architecture. Classical Gothic buildings of the 12th to 16th Centuries were a source of inspiration to 19th-century designers in numerous fields of work. Architectural elements such as pointed arches, steep-sloping roofs and fancy carvings like lace and lattice work were applied to a wide range of Gothic Revival objects. Some examples of Gothic Revival influence can be found in heraldic motifs in coats of arms, furniture with elaborate painted scenes like the whimsical Gothic detailing in English furniture is traceable as far back as Lady Pomfret's house in Arlington Street, London (1740s), and Gothic fretwork in chairbacks and glazing patterns of bookcases is a familiar feature of Chippendale's ''Director'' (1754, 1762), where, for example, the three-part bookcase employs Gothic details with Rococo profusion, on a symmetrical form. Abbotsford in the Scottish Borders

The Scottish Borders is one of 32 council areas of Scotland. It is bordered by West Lothian, Edinburgh, Midlothian, and East Lothian to the north, the North Sea to the east, Dumfries and Galloway to the south-west, South Lanarkshire to the we ...

, rebuilt from 1816 by Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

and paid for by the profits from his hugely successful, historical novels, exemplifies the "Regency Gothic" style. Gothic Revival also includes the reintroduction of medieval clothes and dances in historical re-enactments staged especially in the second part of the 19th century, although one of the first, the Eglinton Tournament

The Eglinton Tournament of 1839 was a reenactment of a medieval joust and revel held in North Ayrshire, Scotland between 28 and 30 August. It was funded and organized by Archibald, Earl of Eglinton, and took place at Eglinton Castle in Ayrshir ...

of 1839, remains the most famous.

During the Bourbon Restoration in France

The Bourbon Restoration was the period of French history during which the House of Bourbon returned to power after the fall of Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte in 1814 and 1815. The second Bourbon Restoration lasted until the July Revolution of 183 ...

(1814–1830) and the Louis-Philippe

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his throne ...

period (1830–1848), Gothic Revival motifs start to appear, together with revivals of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and of Rococo

Rococo, less commonly Roccoco ( , ; or ), also known as Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and dramatic style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpte ...

. During these two periods, the vogue for medieval things led craftsmen to adopt Gothic decorative motifs in their work, such as bell turrets, lancet arches, trefoil

A trefoil () is a graphic form composed of the outline of three overlapping rings, used in architecture, Pagan and Christian symbolism, among other areas. The term is also applied to other symbols with a threefold shape. A similar shape with f ...

s, Gothic tracery and rose window

Rose window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in Gothic cathedrals and churches. The windows are divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The term ''rose window'' wa ...

s. This style was also known as "Cathedral style" ("À la catédrale").

By the mid-19th century, Gothic traceries and niches could be inexpensively re-created in wallpaper

Wallpaper is used in interior decoration to cover the interior walls of domestic and public buildings. It is usually sold in rolls and is applied onto a wall using wallpaper paste. Wallpapers can come plain as "lining paper" to help cover uneve ...

, and Gothic blind arcading could decorate a ceramic pitcher. Writing in 1857, J. G. Crace

John Gregory Crace (26 May 1809 – 13 August 1889) was a British Interior decoration, interior decorator and author.

Early life and education

The Crace family had been prominent London Interior decoration, interior decorators since Edward Crac ...

, an influential decorator from a family of influential interior designers, expressed his preference for the Gothic style: "In my opinion there is no quality of lightness, elegance, richness or beauty possessed by any other style... rin which the principles of sound construction can be so well carried out". The illustrated catalogue for the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

of 1851 is replete with Gothic detail, from lacemaking and carpet designs to heavy machinery. Nikolaus Pevsner's volume on the exhibits at the Great Exhibition, ''High Victorian Design'' published in 1951, was an important contribution to the academic study of Victorian taste and an early indicator of the later 20th century rehabilitation of Victorian architecture and the objects with which they decorated their buildings.

In 1847, eight thousand British crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, parti ...

coins were minted in proof

Proof most often refers to:

* Proof (truth), argument or sufficient evidence for the truth of a proposition

* Alcohol proof, a measure of an alcoholic drink's strength

Proof may also refer to:

Mathematics and formal logic

* Formal proof, a co ...

condition with the design using an ornate reverse in keeping with the revived style. Considered by collectors to be particularly beautiful, they are known as 'Gothic crowns'. The design was repeated in 1853, again in proof. A similar two shilling coin, the 'Gothic florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin (in Italian ''Fiorino d'oro'') struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time.

It had 54 grains () of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a pu ...

' was minted for circulation from 1851 to 1887.

Romanticism and nationalism

French neo-Gothic had its roots in the French medieval Gothic architecture, where it was created in the 12th century. Gothic architecture was sometimes known during the medieval period as the "Opus Francigenum", (the "French Art"). French scholar Alexandre de Laborde wrote in 1816 that "Gothic architecture has beauties of its own", which marked the beginning of the Gothic Revival in France. Starting in 1828, Alexandre Brogniart, the director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, produced fired enamel paintings on large panes of plate glass, for King Louis-Philippe's

French neo-Gothic had its roots in the French medieval Gothic architecture, where it was created in the 12th century. Gothic architecture was sometimes known during the medieval period as the "Opus Francigenum", (the "French Art"). French scholar Alexandre de Laborde wrote in 1816 that "Gothic architecture has beauties of its own", which marked the beginning of the Gothic Revival in France. Starting in 1828, Alexandre Brogniart, the director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, produced fired enamel paintings on large panes of plate glass, for King Louis-Philippe's Chapelle royale de Dreux

The Royal Chapel of Dreux () situated in Dreux, France, is the traditional burial place of members of the House of Orléans. It is an important early building in the French adoption of Gothic Revival architecture, despite being topped by a dome. ...

, an important early French commission in Gothic taste, preceded mainly by some Gothic features in a few '' jardins paysagers''.

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

's historical romance novel ''The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

''The Hunchback of Notre-Dame'' (, originally titled ''Notre-Dame de Paris. 1482'') is a French Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. The title refers to the Notre-Dame Cathedral, which features prominently throughout the novel. I ...

'' appeared, in which the great Gothic cathedral of Paris was at once a setting and a protagonist in a hugely popular work of fiction. Hugo intended his book to awaken a concern for the surviving Gothic architecture left in Europe, however, rather than to initiate a craze for neo-Gothic in contemporary life. In the same year that ''Notre-Dame de Paris'' appeared, the new restored Bourbon monarchy established an office in the Royal French Government of Inspector-General of Ancient Monuments, a post which was filled in 1833 by Prosper Mérimée

Prosper Mérimée (; 28 September 1803 – 23 September 1870) was a French writer in the movement of Romanticism, one of the pioneers of the novella, a short novel or long short story. He was also a noted archaeologist and historian, an import ...

, who became the secretary of a new Commission des Monuments Historiques in 1837. This was the Commission that instructed Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (; 27 January 181417 September 1879) was a French architect and author, famous for his restoration of the most prominent medieval landmarks in France. His major restoration projects included Notre-Dame de Paris, ...

to report on the condition of the Abbey of Vézelay in 1840. Following this, Viollet le Duc set out to restore most of the symbolic buildings in France including Notre Dame de Paris, Vézelay, Carcassonne

Carcassonne is a French defensive wall, fortified city in the Departments of France, department of Aude, Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. It is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the department.

...

, Roquetaillade castle, Mont-Saint-Michel Abbey

The Mont-Saint-Michel Abbey is an abbey located within the city and island of Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy, in the department of Manche.

The abbey is an essential part of the structural composition of the town the feudal society constructed. ...

on its peaked coastal island, Pierrefonds, and the Palais des Papes

The ( English: Palace of the Popes; ''lo Palais dei Papas'' in Occitan) in Avignon, Southern France, is one of the largest and most important medieval Gothic buildings in Europe. Once a fortress and palace, the papal residence was a seat of We ...

in Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

. When France's first prominent neo-Gothic church was built, the Basilica of Saint-Clotilde, Paris, begun in 1846 and consecrated in 1857, the architect chosen was of German extraction, Franz Christian Gau

Franz Christian Gau (15 June 1790, in Cologne – January 1854, in Paris) was a French architect and archaeologist of German descent.

In 1809 he entered the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Paris, and in 1815 visited Italy and Sicily. In 1817 he went t ...

, (1790–1853); the design was significantly modified by Gau's assistant, Théodore Ballu, in the later stages, to produce the pair of ''flèches'' that crown the west end.

In Germany, there was a renewal of interest in the completion of Cologne Cathedral

Cologne Cathedral (, , officially , English: Cathedral Church of Saint Peter) is a cathedral in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia belonging to the Catholic Church. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the administration of the Archd ...

. Begun in 1248, it was still unfinished at the time of the revival. The 1820s "Romantic" movement brought a new appreciation of the building, and construction work began once more in 1842, marking a German return for Gothic architecture. St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, begun in 1344, was also completed in the mid-19th and early 20th centuries. The importance of the Cologne completion project in German-speaking lands has been explored by Michael J. Lewis, ''"The Politics of the German Gothic Revival: August Reichensperger"''. Reichensperger was himself in no doubt as to the cathedral's central position in Germanic culture; "Cologne Cathedral is German to the core, it is a national monument in the fullest sense of the word, and probably the most splendid monument to be handed down to us from the past".

Because of Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

in the early 19th century, the Germans, French and English all claimed the original Gothic architecture of the 12th century era as originating in their own country. The English boldly coined the term "Early English" for "Gothic", a term that implied Gothic architecture was an English creation. In his 1832 edition of ''Notre Dame de Paris'', author Victor Hugo said "Let us inspire in the nation, if it is possible, love for the national architecture", implying that "Gothic" is France's national heritage. In Germany, with the completion of Cologne Cathedral in the 1880s, at the time its summit was the world's tallest building, the cathedral was seen as the height of Gothic architecture. Other major completions of Gothic cathedrals were of Regensburger Dom (with twin spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spire ...

s completed from 1869 to 1872), Ulm Münster (with a 161-meter tower from 1890) and St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague (1844–1929).

In Belgium, a 15th-century church in

In Belgium, a 15th-century church in Ostend

Ostend ( ; ; ; ) is a coastal city and municipality in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerke, Raversijde, Stene and Zandvoorde, and the city of Ostend proper – the la ...

burned down in 1896. King Leopold II funded its replacement, the Saint Peter's and Saint Paul's Church, a cathedral-scale design which drew inspiration from the neo-Gothic Votive Church in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

and Cologne Cathedral. In Mechelen

Mechelen (; ; historically known as ''Mechlin'' in EnglishMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical context. T ...

, the largely unfinished building drawn in 1526 as the seat of the Great Council of The Netherlands, was not actually built until the early 20th century, although it closely followed Rombout II Keldermans's Brabantine Gothic

Brabantine Gothic, occasionally called Brabantian Gothic, is a significant variant of Gothic architecture that is typical for the Low Countries. It surfaced in the first half of the 14th century at St. Rumbold's Cathedral in the city of Mechele ...

design, and became the 'new' north wing of the City Hall. In Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, the Duomo

''Duomo'' (, ) is an Italian term for a church with the features of, or having been built to serve as a cathedral, whether or not it currently plays this role. The Duomo of Monza, for example, has never been a diocesan seat and is by definitio ...

's temporary façade erected for the Medici-House of Lorraine nuptials in 1588–1589, was dismantled, and the west end of the cathedral stood bare again until 1864, when a competition was held to design a new façade suitable to Arnolfo di Cambio

Arnolfo di Cambio ( – 1300/1310) was an Italian architect and sculptor of the Duecento, who began as a lead assistant to Nicola Pisano. He is documented as being ''capomaestro'' or Head of Works for Florence Cathedral in 1300, and designed th ...

's original structure and the fine campanile

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell to ...

next to it. This competition was won by Emilio De Fabris, and so work on his polychrome design and panels of mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

was begun in 1876 and completed by 1887, creating the Neo-Gothic western façade.

Eastern Europe also saw much Revival construction; in addition to the Hungarian Parliament Building

The Hungarian Parliament Building ( , ), also known as the Parliament of Budapest after its location, is the seat of the National Assembly of Hungary, a notable landmark of Hungary, and a popular tourist destination in Budapest. It is situated o ...

in Budapest, the Bulgarian National Revival

The Bulgarian Revival (, ''Balgarsko vazrazhdane'' or simply: Възраждане, ''Vazrazhdane'', and ), sometimes called the Bulgarian National Revival, was a period of socio-economic development and national integration among Bulgarian pe ...

saw the introduction of Gothic Revival elements into its vernacular ecclesiastical and residential architecture. The largest project of the Slavine School is the Lopushna Monastery cathedral (1850–1853), though later churches such as Saint George's Church, Gavril Genovo display more prominent vernacular Gothic Revival features.

In Scotland, while a similar Gothic style to that used further south in England was adopted by figures including Frederick Thomas Pilkington

Frederick Thomas Pilkington (1832-1898), pupil of his father, was a "Rogue" British architect, practising in the Victorian High Gothic revival style. He designed mostly churches and institutional buildings in Scotland. Typical of his work is ...

(1832–1898) in secular architecture it was marked by the re-adoption of the Scots baronial

Scottish baronial or Scots baronial is an architectural style of 19th-century Gothic Revival architecture, Gothic Revival which Revivalism (architecture), revived the forms and ornaments of historical Architecture of Scotland in the Middle Ages, ...

style. Important for the adoption of the style in the early 19th century was Abbotsford, which became a model for the modern revival of the baronial style. Common features borrowed from 16th- and 17th-century houses included battlemented gateways, crow-stepped gable

A stepped gable, crow-stepped gable, or corbie step is a stairstep type of design at the top of the triangular gable-end of a building. The top of the parapet wall projects above the roofline and the top of the brick or stone wall is stacked in ...

s, pointed turrets and machicolations

In architecture, a machicolation () is an opening between the supporting corbels of a battlement through which defenders could target attackers who had reached the base of the defensive wall. A smaller related structure that only protects key poi ...

. The style was popular across Scotland and was applied to many relatively modest dwellings by architects such as William Burn

William Burn (20 December 1789 – 15 February 1870) was a Scottish architect. He received major commissions from the age of 20 until his death at 81. He built in many styles and was a pioneer of the Scottish Baronial Revival, often referred ...

(1789–1870), David Bryce

David Bryce Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, FRSE FRIBA Royal Scottish Academy, RSA (3 April 1803 – 7 May 1876) was a Scotland, Scottish architect.

Life

Bryce was born at 5 South College Street in Edinburgh, the son of David B ...

(1803–1876), Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

Blore was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's backg ...

(1787–1879), Edward Calvert () and Robert Stodart Lorimer (1864–1929) and in urban contexts, including the building of Cockburn Street in Edinburgh (from the 1850s) as well as the National Wallace Monument

The National Wallace Monument (generally known as the Wallace Monument) is a tower on the shoulder of the Abbey Craig, a hilltop overlooking Stirling in Scotland. It commemorates Sir William Wallace, a 13th- and 14th-century Scottish hero.

...

at Stirling (1859–1869). The reconstruction of Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle () is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were bought ...

as a baronial palace and its adoption as a royal retreat from 1855 to 1858 confirmed the popularity of the style.

In the United States, the first "Gothic stile" church (as opposed to churches with Gothic elements) was Trinity Church on the Green, New Haven, Connecticut. It was designed by Ithiel Town

Ithiel Town (October 3, 1784 – June 13, 1844) was an American architect and civil engineer. One of the first generation of professional architects in the United States, Town made significant contributions to American architecture in the f ...

between 1812 and 1814, while he was building his Federalist-style Center Church, New Haven next to this radical new "Gothic-style" church. Its cornerstone was laid in 1814, and it was consecrated in 1816. It predates St Luke's Church, Chelsea

The Parish Church of St Luke, Chelsea, is an Church of England, Anglican church (building), church, on Sydney Street, Chelsea, London, Chelsea, London SW3, just off the King's Road. Ecclesiastically it is in the Deanery of Chelsea, part of the D ...

, often said to be the first Gothic-revival church in London. Though built of trap rock

Trap rock, also known as either trapp or trap, is any dark-colored, fine-grained, non-granitic intrusive or extrusive igneous rock. Types of trap rock include basalt, peridotite, diabase, and gabbro.Neuendorf, K.K.E., J.P. Mehl, Jr., and J.A ...

stone with arched windows and doors, parts of its tower and its battlements were wood. Gothic buildings were subsequently erected by Episcopal congregations in Connecticut at St John's in Salisbury (1823), St John's in Kent (1823–1826) and St Andrew's in Marble Dale (1821–1823). These were followed by Town's design for Christ Church Cathedral (Hartford, Connecticut) (1827), which incorporated Gothic elements such as buttresses into the fabric of the church. St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Troy, New York, was constructed in 1827–1828 as an exact copy of Town's design for Trinity Church, New Haven, but using local stone; due to changes in the original, St. Paul's is closer to Town's original design than Trinity itself. In the 1830s, architects began to copy specific English Gothic and Gothic Revival Churches, and these "'mature Gothic Revival' buildings made the domestic Gothic style architecture which preceded it seem primitive and old-fashioned".

There are many examples of Gothic Revival architecture in Canada. The first major structure was Notre-Dame Basilica in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

, which was designed in 1824. The capital, Ottawa, Ontario

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

, was predominantly a 19th-century creation in the Gothic Revival style. The Parliament Hill

Parliament Hill (), colloquially known as The Hill, is an area of Crown land on the southern bank of the Ottawa River that houses the Parliament of Canada in downtown Ottawa, Ontario. It accommodates a suite of Gothic revival buildings whose ...

buildings were the preeminent example, of which the original library survives today (after the rest was destroyed by fire in 1916). Their example was followed elsewhere in the city and outlying areas, showing how popular the Gothic Revival movement had become. Other examples of Canadian Gothic Revival architecture in Ottawa are the Victoria Memorial Museum, (1905–1908), the Royal Canadian Mint

The Royal Canadian Mint () is the mint of Canada and a Crown corporation, operating under an act of parliament referred to as the ''Royal Canadian Mint Act''. The shares of the mint are held in trust for the Crown in right of Canada.

The mi ...

, (1905–1908), and the Connaught Building

The Connaught Building is a historic office building in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, owned by Public Services and Procurement Canada. It is located at 555 MacKenzie Avenue, just south of the United States Embassy. To the east, the building looks out o ...

, (1913–1916), all by David Ewart

David Ewart, Imperial Service Order, ISO (18 February 1841 – 6 June 1921) was a Canadians, Canadian architect who served as Chief Dominion Architect from 1896 to 1914.

As chief government architect he was responsible for many of the federal bu ...

.

Gothic as a moral force

Pugin and "truth" in architecture

In the late 1820s, A. W. N. Pugin, still a teenager, was working for two highly visible employers, providing Gothic detailing for luxury goods. For the Royal furniture makers Morel and Seddon he provided designs for redecorations for the elderlyGeorge IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

in a Gothic taste suited to the setting. For the royal silversmiths Rundell Bridge and Co., Pugin provided designs for silver from 1828, using the 14th-century Anglo-French Gothic vocabulary that he would continue to favour later in designs for the new Palace of Westminster. Between 1821 and 1838 Pugin and his father published a series of volumes of architectural drawing

An architectural drawing or architect's drawing is a technical drawing of a building (or building project) that falls within the definition of architecture. Architectural drawings are used by architects and others for a number of purposes: to deve ...

s, the first two entitled, ''Specimens of Gothic Architecture'', and the following three, ''Examples of Gothic Architecture'', that were to remain both in print and the standard references for Gothic Revivalists for at least the next century.

In ''Contrasts: or, a Parallel between the Noble Edifices of the Middle Ages, and similar Buildings of the Present Day'' (1836), Pugin expressed his admiration not only for medieval art but for the whole medieval ethos, suggesting that Gothic architecture was the product of a purer society. In ''The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture'' (1841), he set out his "two great rules of design: 1st, that there should be no features about a building which are not necessary for convenience, construction or propriety; 2nd, that all ornament should consist of enrichment of the essential construction of the building". Urging modern craftsmen to seek to emulate the style of medieval workmanship as well as reproduce its methods, Pugin sought to reinstate Gothic as the true Christian architectural style.

Pugin's most notable project was the Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster is the meeting place of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is located in London, England. It is commonly called the Houses of Parliament after the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two legislative ch ...

in London, after its predecessor was largely destroyed in a fire in 1834. His part in the design consisted of two campaigns, 1836–1837 and again in 1844 and 1852, with the classicist Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was an English architect best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsi ...

as his nominal superior. Pugin provided the external decoration and the interiors, while Barry designed the symmetrical layout of the building, causing Pugin to remark, "All Grecian, Sir; Tudor details on a classic body".

Ruskin and Venetian Gothic

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

supplemented Pugin's ideas in his two influential theoretical works, ''The Seven Lamps of Architecture

''The Seven Lamps of Architecture'' is an extended essay, first published in May 1849 and written by the English art critic and theorist John Ruskin. The 'lamps' of the title are Ruskin's principles of architecture, which he later enlarged upon i ...