The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous

debate

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse, discussion, and oral addresses on a particular topic or collection of topics, often with a moderator and an audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for opposing viewpoints. Historica ...

in the British

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The official title of the debate, as held in the ''

Hansard

''Hansard'' is the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official printe ...

'' parliamentary archive, is Conduct of the War. The debate was initiated by an

adjournment motion enabling the Commons to freely discuss the progress of the

Norwegian campaign. The debate quickly brought to a head widespread dissatisfaction with the conduct of the war by

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

's government.

At the end of the second day, there was a

division of the House for the members to hold a

no confidence motion

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

. The vote was won by the government but by a drastically reduced majority. That led on 10 May to Chamberlain resigning as

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

and the replacement of his

war ministry

In the United Kingdom, war ministry may refer to the following British wartime ministries of the 20th century:

* Lloyd George war ministry (1916–1919)

* Chamberlain war ministry (1939–1940)

* Churchill war ministry

The Churchill w ...

by a broadly based

coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

, which, under

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, governed the United Kingdom until after the end of the war in Europe in May 1945.

Chamberlain's government was criticised not only by the

Opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* ''The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Comedy ...

but also by respected members of his own

Conservative Party. The Opposition forced the vote of no confidence, in which over a quarter of Conservative members voted with the Opposition or

abstained, despite a

three-line whip

A whip is an official of a political party whose task is to ensure party discipline (that members of the party vote according to the party platform rather than their constituents, individual conscience or donors) in a legislature.

Whips ...

. There were calls for national unity to be established by formation of an all-party coalition but it was not possible for Chamberlain to reach agreement with the opposition

Labour and

Liberal parties. They refused to serve under him, although they were willing to accept another Conservative as prime minister. After Chamberlain resigned as prime minister (he remained Conservative Party leader until October 1940), they agreed to serve under Churchill.

Background

In 1937, Neville Chamberlain, then

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

, succeeded

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

as

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

, leading a

National Government overwhelmingly composed of

Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

but supported by small

National Labour and

Liberal National parties. It was opposed by the Labour and Liberal parties. Since assuming power in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

in 1933, the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

had pushed an

irredentist

Irredentism () is one state's desire to annex the territory of another state. This desire can be motivated by ethnic reasons because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to or the same as the population of the parent state. Hist ...

foreign policy. Chamberlain initially attempted to avert war by a policy of

appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

, culminating in the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

of September 1938. This policy was abandoned after Germany ceased the use of diplomatic means to avert war, and became more overtly expansionist with the full

occupation of Czechoslovakia

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

in March 1939.

One of the strongest critics of both appeasement and German aggression was Conservative backbencher

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

who, although he was one of the country's most prominent political figures, had last held government office in 1929. After

Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the United Kingdom and France

declared war on Germany two days later. Chamberlain thereupon created a

war cabinet into which he appointed Churchill as

First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

. It was at this point that a government supporter (possibly

David Margesson

Henry David Reginald Margesson, 1st Viscount Margesson, PC (26 July 1890 – 24 December 1965) was a British Conservative politician, most popularly remembered for his tenure as Government Chief Whip in the 1930s. His reputation was of a stern ...

, the Government Chief Whip) noted privately:

Once Germany had rapidly overrun Poland in September 1939, there was a sustained period of military inactivity for over six months dubbed the "

Phoney War

The Phoney War (; ; ) was an eight-month period at the outset of World War II during which there were virtually no Allied military land operations on the Western Front from roughly September 1939 to May 1940. World War II began on 3 Septembe ...

". On 3 April 1940, Chamberlain said in an address to the Conservative National Union that

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

, the German dictator, "had missed the bus". Only six days later, on 9 April, Germany launched an

attack in overwhelming force on neutral and unprepared Norway after swiftly occupying Denmark. In response, Britain deployed military forces to assist the Norwegians.

Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, had direct responsibility for the conduct of naval operations in the

Norwegian campaign. Before the German invasion, he had pressed the Cabinet to ignore Norway's neutrality, mine its territorial waters and be prepared to seize Narvik, in both cases to disrupt the export of

Swedish iron ore

Swedish iron ore was an important economic and military factor in the European theatre of World War II, as Sweden was the main contributor of iron ore to Nazi Germany. The average percentages by source of Nazi Germany’s iron ore procurement t ...

to Germany during winter months, when the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

was frozen. He had, however, advised that a major landing in Norway was not realistically within Germany's powers. Apart from the naval victory in the

Battles of Narvik

The Battles of Narvik were fought from 9 April to 8 June 1940, as a naval battle in Ofotfjord and as a land battle in the mountains surrounding the north Norwegian town of Narvik, as part of the Norwegian Campaign of the Second World War.

Th ...

, the Norwegian campaign went badly for the British forces, generally because of poor planning and organisation but essentially because military supplies were inadequate and, from 27 April, the Anglo-French forces were obliged to evacuate.

When the House of Commons met on Thursday, 2 May, Labour leader

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

asked: "Is the Prime Minister now able to make a statement on the position in Norway?" Chamberlain was reluctant to discuss the military situation because of the security factors involved but did express a hope that he and Churchill would be able to say much more next week. He went on to make an interim statement of affairs but was not forthcoming about "certain operations (that) are in progress (as) we must do nothing which might jeopardise the lives of those engaged in them". He asked the House to defer comment and question until next week. Attlee agreed and so did Liberal leader

Archibald Sinclair

Archibald Henry Macdonald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso, (22 October 1890 – 15 June 1970), known as Sir Archibald Sinclair between 1912 and 1952, and often as Archie Sinclair, was a British politician and leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Li ...

, except that he requested a debate on Norway lasting more than a single day.

Attlee then presented Chamberlain with a private notice in which he requested a schedule for next week's Commons business. Chamberlain announced that a debate on the general conduct of the war would commence on Tuesday, 7 May. The debate was keenly anticipated in both Parliament and the country. In his diary entry for Monday, 6 May, Chamberlain's

Assistant Private Secretary John Colville wrote that all interest centred on the debate. Obviously, he thought, the government would win through but after facing some very awkward points about Norway. Some of Colville's colleagues including

Lord Dunglass, who was Chamberlain's

Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) at the time, considered the government position to be sound politically, but less so in other respects. Colville worried that "the confidence of the country may be somewhat shaken".

7 May: first day of the debate

Preamble and other business

The Commons sitting on Tuesday, 7 May 1940, began at 14:45 with

Speaker

Speaker most commonly refers to:

* Speaker, a person who produces speech

* Loudspeaker, a device that produces sound

** Computer speakers

Speaker, Speakers, or The Speaker may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* "Speaker" (song), by David ...

Edward FitzRoy

Edward Algernon FitzRoy (24 July 1869 – 3 March 1943) was a British Conservative politician who served as Speaker of the House of Commons from 1928 until his death in 1943.

Early life

FitzRoy was the second son of the 3rd Baron Southampto ...

in the Chair. There followed some private business matters and numerous oral answers to questions raised, many of those being about the British Army.

With these matters completed, the debate on the Norwegian campaign began with a routine

adjournment motion (i.e., "that this house do now adjourn"). Under

Westminster rules in debates like this, wide-ranging discussions of a variety of topics are allowed, and the motion is not usually put to a vote.

At 15:48, Captain David Margesson, the Government

Chief Whip

The Chief Whip is a political leader whose task is to enforce the whipping system, which aims to ensure that legislators who are members of a political party attend and vote on legislation as the party leadership prescribes.

United Kingdom

I ...

, made the adjournment motion. The House proceeded to openly discuss "Conduct of the War", specifically the progress of the Norwegian campaign, and Chamberlain rose to make his opening statement.

Chamberlain's opening speech

Chamberlain began by reminding the House of his statement on Thursday, 2 May, five days earlier, when it was known that British forces had been withdrawn from

Åndalsnes

is a town in Rauma Municipality in Møre og Romsdal county, Norway. Åndalsnes is also the administrative center of Rauma Municipality. It is located along the Isfjorden, at the mouth of the river Rauma, at the north end of the Romsdalen valle ...

. He was now able to confirm that they had also been withdrawn from

Namsos Namsos may refer to:

Places

*Namsos Municipality, a municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway

*Namsos (town)

Namsos is a List of towns and cities in Norway, town and the administrative center of Namsos Municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. ...

to complete the evacuation of Allied forces from central and southern Norway (the campaign in northern Norway continued). Chamberlain attempted to treat the Allied losses as unimportant and claimed that British soldiers "man for man (were) superior to their foes". He praised the "splendid gallantry and dash" of the British forces but acknowledged they were "exposed ... to superior forces with superior equipment".

Chamberlain then said he proposed "to present a picture of the situation" and to "consider certain criticisms of the government". He stated that "no doubt" the withdrawal had created a shock in both the House and the country. At this point, the interruptions began as a Labour member,

Ben Smith shouted: "And abroad", and an unnamed member added: "All over the world".

Chamberlain sarcastically responded that "ministers, of course, must be expected to be blamed for everything". This provoked a heated reaction with several members derisively shouting: "They missed the bus!" The Speaker had to call on members not to interrupt, but they continued to repeat the phrase throughout Chamberlain's speech and he reacted with what has been described as "a rather feminine gesture of irritation". He was eventually forced to defend the original usage of the phrase directly, claiming that he would have expected a German attack on the Allies at the outbreak of war when the difference in armed power was at its greatest.

Chamberlain's speech has been widely criticised.

Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician and writer who served as the sixth President of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981. At various times a Member of Parliamen ...

called it "a tired, defensive speech which impressed nobody". Liberal MP

Henry Morris-Jones said Chamberlain looked "a shattered man" and spoke without his customary self-assurance. When Chamberlain insisted that "the balance of advantage lay on our side", Liberal MP

Dingle Foot

Sir Dingle Mackintosh Foot, QC (24 August 1905 – 18 June 1978) was a British lawyer, Liberal and Labour Member of Parliament, and Solicitor General for England and Wales in the first government of Harold Wilson.

Family and education

Born ...

could not believe what he was hearing and said Chamberlain was denying the fact that Britain had suffered a major defeat. The backbench Conservative MP

Leo Amery

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery (22 November 1873 – 16 September 1955), also known as L. S. Amery, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician and journalist. During his career, he was known for his interest in ...

said Chamberlain's speech left the House in a restive and depressed, though not yet mutinous, state of mind. Amery believed that Chamberlain was "obviously satisfied with things as they stood" and, in the government camp, the mood was actually positive as they believed they were, in John Colville's words, "going to get away with it".

Attlee's response to Chamberlain

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

responded as Leader of the Opposition. He quoted some of Chamberlain's and Churchill's recent confident assertions about the likely victory of the British. Ministers' statements and, even more so, the press, guided (or deliberately left uncorrected) by the government, had painted far too optimistic a picture of the Norwegian campaign. Given the level of confidence created, the setback had generated widespread disappointment. Attlee now raised the issue of government planning which would be revisited by several later speakers:

Chamberlain had announced additional powers being granted to Churchill which amounted to him having direction of the Chiefs of Staff. Attlee seized on this as an example of government incompetence, though without blaming Churchill, by saying:

Attlee struck a theme here that would recur throughout the debate – that the government was incompetent but not Churchill himself, even though he was part of it, as he had suffered from what Jenkins calls a misdirection of his talents. Jenkins remarks that Churchill's potential had not been fully utilised and, most importantly, he was clean of the stain of appeasement.

Chamberlain had been heckled during his speech for having "missed the bus" and he made his case worse by desperately trying, and failing, to excuse his use of that expression a month earlier. In doing so, he provided Attlee with an opportunity. During the conclusion of his response, Attlee said:

Attlee's closing words were a direct attack on all Conservative members, blaming them for shoring up ministers whom they knew to be failures:

Leo Amery said later that Attlee's restraint, in not calling for a

division of the House (i.e., a vote), was of greater consequence than all his criticisms because, Amery believed, it made it much easier for Conservative members to be influenced by the debate's opening day.

Sinclair's response to Chamberlain

Sir

Archibald Sinclair

Archibald Henry Macdonald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso, (22 October 1890 – 15 June 1970), known as Sir Archibald Sinclair between 1912 and 1952, and often as Archie Sinclair, was a British politician and leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Li ...

, the leader of the Liberals, then spoke. He too was critical and began by comparing military and naval staff efficiency, which he considered proven, with political inefficiency:

He drew from Chamberlain the admission that whilst troops had been held in readiness to be sent to Norway, no troopships had been retained to send them in. Sinclair gave instances of inadequate and defective equipment and of disorganisation reported to him by servicemen returning from Norway. Chamberlain had suggested that Allied plans had failed because the Norwegians had not put up the expected resistance to the Germans. Sinclair reported that the servicemen "paid a high tribute to the courage and determination with which the Norwegians fought alongside them. They paid a particular tribute to the Norwegian ski patrols. Norwegians at Lillehammer for seven days held up with rifles only a German force with tanks, armoured cars, bombing aeroplanes and all the paraphernalia of modern war".

He concluded his speech by calling for Parliament to "speak out (and say) we must have done with half-measures (to promote) a policy for the more vigorous conduct of the war".

No longer an ordinary debate

The rest of the first day's debate saw speeches both supporting and criticising the Chamberlain government. Sinclair was followed by two ex-soldiers, Brigadier

Henry Page Croft for the Conservatives and Colonel

Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indu ...

for Labour. Derided by Labour, Croft made an unconvincing case in support of Chamberlain and described the press as "the biggest dictator of all".

Wedgwood denounced Croft for his "facile optimism, that saps the morale of the whole country". Wedgwood warned of the dangers inherent in trying to negotiate with Hitler and urged prosecution of the war by "a government which can take this war seriously".

Attending the debate was National Labour MP

Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British politician, writer, broadcaster and gardener. His wife was Vita Sackville-West.

Early life and education

Nicolson was born in Tehran, Persia, the youngest son of dipl ...

who was arguably the pre-eminent diarist of British politics in the twentieth century. He took special notice of a comment made by Wedgwood which, in Nicolson's view, transformed "an ordinary debate (into) a tremendous conflict of wills". Wedgwood had asked if the government was preparing any plan to prevent an invasion of Great Britain. A Conservative MP, Vice Admiral

Ernest Taylor, interrupted and asked him if he had forgotten the Royal Navy. Wedgwood countered that with:

Moments later, Admiral of the Fleet Sir

Roger Keyes

Admiral of the Fleet Roger John Brownlow Keyes, 1st Baron Keyes, (4 October 1872 – 26 December 1945) was a British naval officer.

As a junior officer he served in a corvette operating from Zanzibar on slavery suppression missions. Earl ...

, the Conservative Member for

Portsmouth North, arrived in the chamber and caused a stir because he was resplendent in his uniform with gold braid and six rows of medal ribbons. He squeezed into a bench just behind Nicolson who passed him a piece of paper with Wedgwood's remark scribbled on it. Keyes went to the Speaker and asked to be called next as the honour of the navy was at stake, though he had really come to the House with the intention of criticising the Chamberlain government.

Keyes: "I speak for the fighting Navy"

When Wedgwood sat down, the Speaker called Keyes, who began by denouncing Wedgwood's comment as "a damned insult". The House, especially

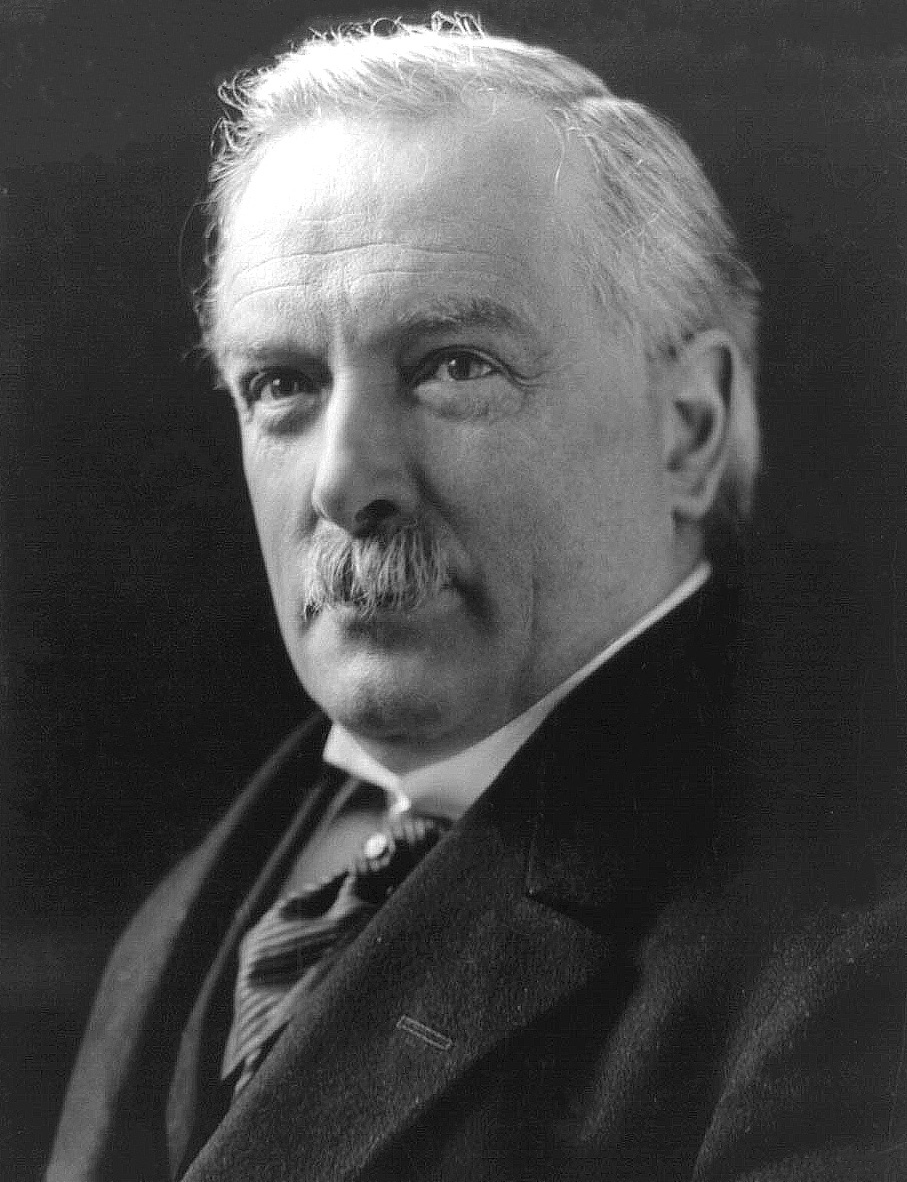

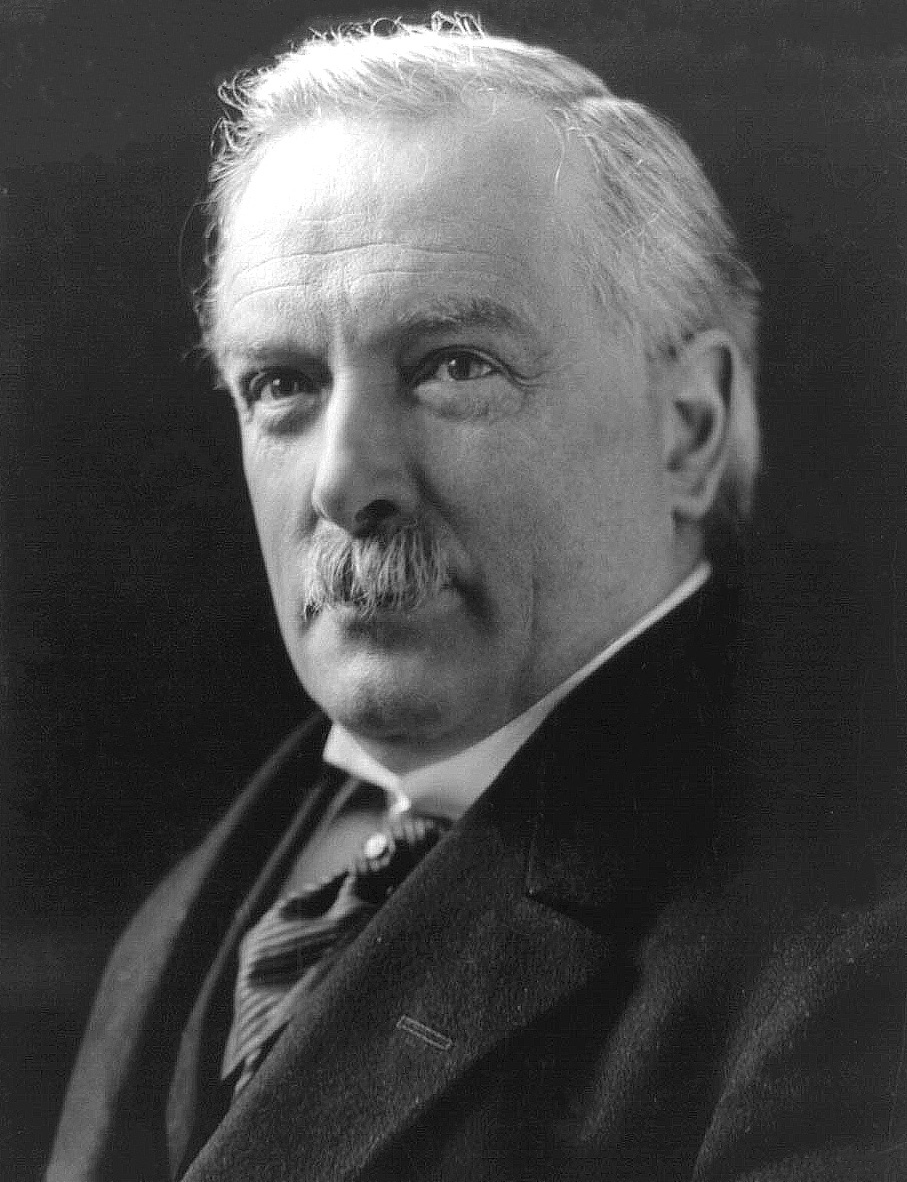

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, "roared its applause". Keyes quickly moved on and became the debate's first Tory rebel. As Jenkins puts it, Keyes "turned his guns on Chamberlain" but with the proviso that he was longing to see "proper use made of Churchill's great abilities".

Keyes was a hero of the First World War representing a naval town and an

Admiral of the Fleet

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

(though no longer on the

active list). He spoke mostly on the conduct of naval operations, particularly the

abortive operations to retake Trondheim. Keyes told the House:

As the House listened in silence, Keyes finished by quoting

Horatio Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

's evocation of

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

:

It was 19:30 when Keyes sat down to "thunderous applause". Nicolson wrote that Keyes's speech was the most dramatic he had ever heard, and the debate from that point on was no longer an investigation of the Norwegian campaign but "a criticism of the government's whole war effort".

Jones and Bellenger

The next two speakers were National Liberal

Lewis Jones and Labour's

Frederick Bellenger

Captain Frederick John Bellenger (23 July 1894 – 11 May 1968) was a British surveyor, soldier and politician.

Early life

Born in Bethnal Green, London, he was the son of Eugene Bernard Bellenger, a dairyman, and his wife Isabella Annette ''n ...

, who was still a serving army officer and was evacuated from France only a month later. Jones, who supported Chamberlain, was unimpressive and was afterwards accused of introducing party politics into the debate. There was a general exodus from the chamber as Jones was speaking. Bellenger, who repeated much of Attlee's earlier message, called "in the public interest" for a government "of a different character and a different nature".

Amery: "In the name of God, go!"

When Bellenger sat down, it was 20:03 and the Deputy Speaker,

Dennis Herbert, called on

Leo Amery

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery (22 November 1873 – 16 September 1955), also known as L. S. Amery, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician and journalist. During his career, he was known for his interest in ...

, who had been trying for several hours to gain the Speaker's attention. Amery later remarked that there were "barely a dozen" members present (Nicolson was among them) as he began to speak. Nicolson, who expected a powerfully critical speech from Amery, wrote that the temperature continued to rise as Amery began and his speech soon "raised it far beyond the fever point".

Amery had an ally in

Clement Davies

Edward Clement Davies (19 February 1884 – 23 March 1962) was a Welsh politician and leader of the Liberal Party from 1945 to 1956.

Early life and education

Edward Clement Davies was born on 19 February 1884 in Llanfyllin, Montgomeryshire, ...

, chairman of the

All Party Action Group

All or ALL may refer to:

عرص

Biology and medicine

* Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a cancer

* Anterolateral ligament, a ligament in the knee

* ''All.'', taxonomic author abbreviation for Carlo Allioni (1728–1804), Italian physician and profe ...

which included some sixty MPs. Davies had been a National Liberal subject to the National Government whip but, in protest against Chamberlain, he had resigned it in December 1939 and crossed the floor of the House to rejoin the Liberals in opposition. Like many other members, Davies had gone to eat when Jones began speaking but, on hearing that Amery had been called, he rushed back to the chamber. Seeing that it was nearly empty, Davies approached Amery and urged him to deliver his full speech both to state his full case against the government and also to give Davies time to collect a large audience. Very soon, even though it was the dinner hour, the House began filling rapidly.

Amery's speech is one of the most famous in parliamentary history. As Davies had requested, he played for time until the chamber was nearly full. For much of the speech, the most notable absentee was Chamberlain himself, who was at

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

for an audience with the

King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

. Amery began by criticising the government's planning and execution of the Norway campaign, especially their unpreparedness for it despite intelligence warning of likely German intervention and the clear possibility of some such response to the planned British infraction of Norwegian neutrality by the mining of Norwegian territorial waters. He gave an analogy from his own experience which illustrated the government's lack of initiative:

As tension increased in the House and Amery found himself speaking to a "crescendo of applause",

Edward Spears

Major-General Sir Edward Louis Spears, 1st Baronet, (7 August 1886 – 27 January 1974) was a British Army officer and politician. He served as a liaison officer between British and French forces during both World Wars. From 1917 to 1920, he ...

thought he was hurling huge stones at the government glasshouse with "the effect of a series of deafening explosions". Amery widened his scope to criticise the government's whole conduct of the war to date. He moved towards his conclusion by calling for the formation of a "real" National Government in which the

Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union center, national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions that collectively represent most unionised workers in England and Wales. There are 48 affiliated unions with a total of ...

must be involved to "reinforce the strength of the national effort from inside".

Although sources are somewhat divided on the point, there is a consensus among them that Chamberlain had arrived back in the chamber to hear Amery's conclusion. Nicolson recorded Chamberlain as sitting on a "glum and anxious front bench". Amery said:

Amery delivered the last six words in a near whisper, pointing at Chamberlain as he did so. He sat down and the government's opponents cheered him.

Afterwards, Lloyd George told Amery that his ending was the most dramatic climax he had heard to any speech. Amery himself said he thought he had helped push the Labour Party into forcing a division next day.

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

said later that Amery's speech "effectively destroyed the Chamberlain government".

Later speeches

It was 20:44 when Amery sat down and the debate continued until 23:30. The next speech was by

Sir Archibald Southby, who tried to defend Chamberlain.

He declared that Amery's speech would "certainly give great satisfaction in Berlin" and he was shouted down.

Bob Boothby interrupted and said that "it will give greater satisfaction in this country".

Southby was followed by Labour's

James Milner

James Philip Milner (born 4 January 1986) is an English professional footballer who plays as a midfielder for club Brighton & Hove Albion. A versatile player, Milner has played in multiple positions, including on either wing, in midfield and ...

who expressed the profound dissatisfaction with recent events of the majority of his constituents in Leeds. He called for "drastic change" to be made if Great Britain was to win the war.

Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton

Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton, PC (4 April 1883 – 26 August 1962), styled Viscount Turnour until 1907, was an Irish peer and British politician who served as a Member of Parliament for 47 years, attaining the rare distinction of servin ...

spoke next, commencing at 21:28. Although a Conservative, he began by saying that there was a great deal in Milner's speech with which he was in agreement, but almost nothing in Southby's with which he could agree.

The next speaker was

Arthur Greenwood

Arthur Greenwood (8 February 1880 – 9 June 1954) was a British politician. A prominent member of the Labour Party from the 1920s until the late 1940s, Greenwood rose to prominence within the party as secretary of its research department fr ...

, the Labour deputy leader. He gave what Jenkins calls "a robust Labour wind-up". In his conclusion, Greenwood called for "an active, vigorous, imaginative direction of the war" which had so far been lacking as the government was passive and on the defensive because "(as) the world must know, we have never taken the initiative in this war". Summing up for the government was

Oliver Stanley

Oliver Frederick George Stanley (4 May 1896 – 10 December 1950) was a prominent British Conservative politician who held many ministerial posts before his early death.

Background and education

Stanley was the second son of Edward Stanley, 1 ...

, the

Secretary of State for War

The secretary of state for war, commonly called the war secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The secretary of state for war headed the War Offic ...

, whose reply to Greenwood has been described as ineffective.

8 May: second day and division

Morrison: "We must divide the House"

It is generally understood that Labour did not intend a division before the debate began but Attlee, after hearing the speeches by Keyes and Amery, realised that discontent within Tory ranks was far deeper than they had thought. A meeting of the party's Parliamentary Executive was held on Wednesday morning and Attlee proposed forcing a division at the end of the debate that day. There were a handful of dissenters, including

Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 – 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreig ...

, but they were outvoted at a second meeting later on.

As a result, when

Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the Cabinet as a member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minist ...

reopened the debate just after 16:00, he announced that:

Jenkins says the Labour decision to divide turned the routine adjournment motion into "the equivalent of a vote of censure". Earlier in his opening address, Morrison had focused his criticism on Chamberlain,

John Simon and

Samuel Hoare who were the three ministers most readily associated with appeasement.

Chamberlain: "I have friends in the House"

Hoare, the

Secretary of State for Air

The Secretary of State for Air was a secretary of state position in the British government that existed from 1919 to 1964. The person holding this position was in charge of the Air Ministry. The Secretary of State for Air was supported by ...

, was scheduled to speak next but Chamberlain insisted on replying to Morrison and made an ill-judged and disastrous intervention. Chamberlain appealed not for national unity but for the support of his friends in the House:

That shocked many present who regarded it as divisive to be so explicit in relying on whipped support from his own party. Bob Boothby, a Conservative MP who was a strong critic of Chamberlain, called out: "Not I"; and received a withering glare from Chamberlain. The stress on "friends" was considered partisan and divisive, reducing politics at a time of crisis from national level to personal level.

Hoare followed Chamberlain and struggled to cope with many of the questions being fired at him about the air force, at one point failing to realise the difference between the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

and the

Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is the naval aviation component of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy (RN). The FAA is one of five :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, RN fighting arms. it is a primarily helicopter force, though also operating the Lockhee ...

. He sat down at 17:37 and was succeeded by David Lloyd George.

Lloyd George: "the worst strategic position in which this country has ever been placed"

Lloyd George had been prime minister during the last two years of the First World War. He was now 77, and it was to be his last major contribution to debate in the House in which he had sat for 50 years. There was personal animosity between Lloyd George and Chamberlain. The latter's appeal to friends gave Lloyd George the opportunity for retribution. First, he attacked the conduct of the campaign and began by dismissing Hoare's entire speech in a single sentence:

Lloyd George then began his main attack on the government by focusing on the lack of planning and preparation:

Emphasising the gravity of the situation, he argued that Britain was in the worst position strategically that it had ever been as a result of foreign policy failures, which he began to review from the 1938

Munich agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

onwards. Interrupted at this point, he retorted:

Lloyd George went on to say that British prestige had been greatly impaired, especially in America. Before the events in Norway, he claimed, the Americans had been in no doubt that the Allies would win the war, but now they were saying it would be up to them to defend democracy. After dealing with some interruptions, Lloyd George criticised the rate of re-armament pre-war and to date:

Churchill and Chamberlain intervene in Lloyd George's speech

Dealing with an intervention at this point, Lloyd George said, in passing, that he did not think that the First Lord was entirely responsible for all the things that happened in Norway. Churchill intervened and said:

In answer, Lloyd George said:

Jenkins calls this "a brilliant metaphor" but wonders if it was spontaneous. It produced laughter throughout the House, except on the government front bench where, with one exception, all the faces were stony. A spectator in the gallery,

Baba Metcalfe, recorded that the exception was Churchill himself. She recalled him swinging his legs and trying hard not to laugh. When things calmed down, Lloyd George resumed and now turned his fire onto Chamberlain personally:

Chamberlain stood and, leaning over the despatch box, demanded:

Lloyd George: Chamberlain "should sacrifice the seals of office"

Lloyd George responded to that intervention with a direct call for Chamberlain to resign:

There was silence as Lloyd George sat down and one observer said that all the frustrations of the past eight months had been released. Chamberlain was deeply perturbed and, two days later, told a friend that he had never heard anything like it in Parliament. Churchill was overheard saying to

Kingsley Wood

Sir Howard Kingsley Wood (19 August 1881 – 21 September 1943) was a British Conservative politician. The son of a Wesleyan Methodist minister, he qualified as a solicitor, and successfully specialised in industrial insurance. He became a memb ...

that it was going to be "damned difficult" for him (Churchill) doing his summary later on. Jenkins says the speech recalled Lloyd George in his prime. It was his best of many years, and his last of any real impact.

Other speakers

It was 18:10 when Lloyd George concluded and some four hours later that Churchill began his summary to wind up the government's case ahead of the division. In the interim, several speakers were called to argue both for and against the government. They included long-serving Liberal National

George Lambert, Sir

Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, Cripps first entered Parliament at a 1931 Bristol East by-election ...

,

Alfred Duff Cooper,

George Hicks,

George Courthope

Sir George Courthorpe (3 June 1616 – 18 November 1685) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1656 and 1679.

Courthorpe was the son of George Courthorpe, of Ticehurst, Sussex. He matriculated at University Coll ...

,

Robert Bower,

Alfred Edwards, and

Henry Brooke. The last of these, Brooke, finished at 21:14 and gave way to

A. V. Alexander

Albert Victor Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Hillsborough (1 May 1885 – 11 January 1965) was a British Labour and Co-operative politician. He was three times First Lord of the Admiralty, including during the Second World War, and then Minis ...

who wound up for Labour and put forward certain questions that Churchill as First Lord might answer. His final point, however, was to criticise Chamberlain for his appeal to friendship:

Jenkins describes Alexander as someone who tried, despite being completely different in character and personality, to make of himself a "mini-Churchill". On this occasion, he did present Churchill with some awkward questions about Norway but, as with other speakers before him, it was done with genuine respect amidst severe criticism of Chamberlain, Hoare, Simon and Stanley in particular. There was some embarrassment for Churchill in that he was late in returning to the House for Alexander's speech and Chamberlain had to excuse his absence. He arrived just in time for Alexander's questions about Norway.

Churchill winds up for the Government

Churchill was called to speak at 22:11, the first time in eleven years that he had wound up a debate on behalf of the government. Many members believed that it was the most difficult speech of his career because he had to defend a reverse without damaging his own prestige. It was widely felt that he achieved it because, as Nicolson described it, he said not one word against Chamberlain's government and yet, by means of his manner and his skill as an orator, he created the impression of being nothing to do with them.

The first part of Churchill's speech was, as he said it would be, about the Norwegian campaign. The second part, concerning the vote of censure which he called a new issue that had been sprung upon the House at five o'clock, he said he would deal with in due course.

Churchill proceeded to defend the conduct of the Norwegian campaign with some robustness, although there were several omissions such as his insistence that Narvik be blocked off with a minefield. He explained that even the successful use of the battleship at Narvik had put her at risk from many hazards. Had any come to pass, the operation, now hailed as an example of what should have been done elsewhere, would have been condemned as foolhardy:

As for the lack of action at Trondheim, Churchill said it was not because of any perceived danger, but because it was thought unnecessary. He reminded the House that the campaign continued in northern Norway, at Narvik in particular but he would not be drawn into giving any predictions about it. Instead, he attacked the government's critics by deploring what he called a cataract of unworthy suggestions and actual falsehoods during the last few days:

Churchill then had to deal with interruptions and an intervention by Arthur Greenwood who wanted to know if the war cabinet had delayed action at Trondheim. Churchill denied that and advised Greenwood to dismiss such delusions. Soon afterwards, he reacted to a comment by Labour MP

Manny Shinwell

Emanuel Shinwell, Baron Shinwell, (18 October 1884 – 8 May 1986) was a British politician who served as a government minister under Ramsay MacDonald and Clement Attlee. A member of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, he served as a Member of ...

:

This produced a general uproar led by the veteran Scottish Labour member

Neil Maclean, said to be the worse for drink, who demanded withdrawal of the word "skulks". The Speaker would not rule on the matter and Churchill defiantly refused to withdraw the comment, adding that:

Having defended the conduct of the naval operations in the Norwegian campaign at some length, Churchill now said little about the proposed vote, other than to complain about such short notice:

He concluded by saying:

Churchill sat down but the rowdiness continued with catcalls from both sides of the House and

Chips Channon later wrote that it was "like

Bedlam". Labour's

Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 – 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreig ...

wrote that a good deal of riot developed, some of it rather stupid, towards the end of the speech.

Division

At 23:00, the Speaker rose to put the question "that this House do now adjourn". There was minimal dissent and he announced the division, calling for the Lobby to be cleared. The division was in effect a

no confidence motion

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

or, as Churchill called it in his closing speech, a vote of censure. Of the total 615 members, it has been estimated that more than 550 were present when the division was called but only 481 voted.

The government's notional majority was 213, but 41 members who normally supported the government voted with the Opposition, while an estimated 60 other Conservatives deliberately abstained. The government still won the vote by 281 to 200, but its majority was reduced to 81. Jenkins says that would have been perfectly sustainable in most circumstances, but not when Britain was losing the war and it was clear that unity and leadership were so obviously lacking. In these circumstances the reversal was devastating, and Chamberlain left the chamber pale and grim.

Among the Conservatives, Chips Channon and other Chamberlain supporters shouted "

Quislings

''Quisling'' (, ) is a term used in Scandinavian languages and in English to mean a citizen or politician of an occupied country who collaborates with an enemy occupying force; it may also be used more generally as a synonym for ''traitor'' or ...

" and "Rats" at the rebels, who replied with taunts of "Yes-men". Labour's Josiah Wedgwood led the singing of "

Rule Britannia

"Rule, Britannia!" is a British patriotic song, originating from the 1740 poem "Rule, Britannia" by James Thomson and set to music by Thomas Arne in the same year. It is most strongly associated with the Royal Navy, but is also used by the ...

", joined by Conservative rebel

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

of the Noes; that gave way to cries of "Go!" as Chamberlain left the chamber. Amery, Keyes, Macmillan and Boothby were among the rebels voting with Labour. Others were

Nancy Astor

Nancy Witcher Astor, Viscountess Astor (19 May 1879 – 2 May 1964) was an American-born British politician who was the first woman seated as a Member of Parliament (MP), serving from 1919 to 1945. Astor was born in Danville, Virginia and rai ...

,

John Profumo

John Dennis Profumo ( ; 30 January 1915 – 9 March 2006) was a British politician whose career ended in 1963 after a sexual relationship with the 19-year-old model Christine Keeler in 1961. The scandal, which became known as the Profumo affai ...

,

Quintin Hogg,

Leslie Hore-Belisha

Isaac Leslie Hore-Belisha, 1st Baron Hore-Belisha, PC (; 7 September 1893 – 16 February 1957) was a British Liberal, then National Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) and Cabinet Minister. He later joined the Conservative Party. He proved h ...

and Edward Spears but not some expected dissidents such as

Duncan Sandys

Duncan Edwin Duncan-Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a ...

, who abstained, and

Brendan Bracken

Brendan Rendall Bracken, 1st Viscount Bracken (15 February 1901 – 8 August 1958), was an Irish-born businessman, politician and a Minister of Information and First Lord of the Admiralty in Winston Churchill's War Cabinet.

He is best remembe ...

who, in Jenkins's words, "followed

hurchill'sexample rather than his interest and voted with the government". Colville in his diary wrote that the government was "fairly satisfied" but acknowledged that reconstruction of the Cabinet was necessary; "the shock they have received may be a healthy one".

9 May: third day and conclusion

The debate continued into a third day but, with the division having been held at the end of the second day, the final day was really a matter of wrapping up. Starting at 15:18, there were only four speakers and the last of them was Lloyd George who spoke mostly about his own time as prime minister in the First World War and at the

1919 Paris Peace Conference

Events

January

* January 1

** The Czechoslovak Legions occupy much of the self-proclaimed "free city" of Bratislava, Pressburg (later Bratislava), enforcing its incorporation into the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

** HMY Iolaire, HMY '' ...

. He concluded by blaming the democracies for not carrying out the pledges made at that time with the result that Nazism had arisen in Germany. When he finished, shortly before 16:00, the question "that this House do now adjourn" was raised and agreed to, thus concluding the Norway Debate.

Aftermath

On 9 and 10 May, Chamberlain attempted to form a coalition government with Labour and Liberal participation. They indicated an unwillingness to serve under him but said they probably would join the government if another Conservative became prime minister. When Germany began its

western offensive on the morning of 10 May, Chamberlain seriously considered staying on but, after receiving final confirmation from Labour that they required his resignation, he decided to stand down and advised the King to send for Churchill as his successor.

Gaining the support of both Labour and the Liberals, Churchill formed a coalition government. His war cabinet at first consisted of himself, Attlee, Greenwood, Chamberlain and Halifax. The coalition lasted until the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945. On 23 May 1945, Labour left the coalition to begin their

general election campaign and Churchill resigned as prime minister. The King asked him to form a new government, known as the

Churchill caretaker ministry

The Churchill caretaker ministry was a short-term British government in the latter stages of the Second World War, from 23 May to 26 July 1945. The prime minister was Winston Churchill, leader of the Conservative Party. This government succeed ...

, until the election was held in July. Churchill agreed and his new ministry, essentially a Conservative one, held office for the next two months until it was replaced by the first

Attlee ministry

Clement Attlee was invited by King George VI to form the first Attlee ministry in the United Kingdom on 26 July 1945, succeeding Winston Churchill as prime minister of the United Kingdom. The Labour Party (UK), Labour Party had won a landslide ...

after Labour's election victory.

Place in parliamentary culture

The Norway debate is regarded as a high point in British parliamentary history, coming as it did at a time when Great Britain faced its gravest danger. The former prime minister, David Lloyd George, said the debate was the most momentous in the history of Parliament. The future prime minister, Harold Macmillan, believed that the debate changed British history, perhaps world history.

In his biography of Churchill, Roy Jenkins describes the debate as "by a clear head both the most dramatic and the most far-reaching in its consequences of any parliamentary debate of the twentieth century". He compares it with "its nineteenth-century rivals" (e.g., the

Don Pacifico debate of 1850) and concludes that "even more followed from the 1940 debate" as it transformed the history of the next five years.

Andrew Marr

Andrew William Stevenson Marr (born 31 July 1959) is a British journalist, author, broadcaster and presenter. Beginning his career as a political commentator at ''The Scotsman,'' he subsequently edited ''The Independent'' newspaper from 1996 to ...

wrote that the debate was "one of the greatest parliamentary moments ever and little about it was inevitable". The plotters against Chamberlain succeeded despite being deprived of their natural leader, since Churchill was in the cabinet and obliged to defend it. Marr notes the irony of Amery's closing words which were originally directed ''against'' Parliament by Cromwell, who was speaking ''for'' military dictatorship.

When asked to choose the most historic and memorable speech for a volume commemorating the centenary of ''

Hansard

''Hansard'' is the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official printe ...

'' as an official report of the House of Commons, former Speaker

Betty Boothroyd

Betty Boothroyd, Baroness Boothroyd (8 October 1929 – 26 February 2023), was a British politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), member of Parliament (MP) for West Bromwich (UK Parliament constituency), West Bromwich an ...

chose Amery's speech in the debate, "Amery, by elevating patriotism above party, showed the backbencher's power to help change the course of history".

Betty Boothroyd

Betty Boothroyd, Baroness Boothroyd (8 October 1929 – 26 February 2023), was a British politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), member of Parliament (MP) for West Bromwich (UK Parliament constituency), West Bromwich an ...

, "Ferocious attack that spelt the end for Chamberlain and opened the way for Churchill", in "Official Report ansard, Centenary Volume, House of Commons 2009, p. 91.

Notes

Citations

General and cited references

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

* Kelly, Bernard (2009). "Drifting Towards War: The British Chiefs of Staff, the USSR and the Winter War, November 1939 – March 1940", ''Contemporary British History'', (2009) 23:3 pp. 267–291,

* Redihan, Erin (2013). "Neville Chamberlain and Norway: The Trouble with 'A Man of Peace' in a Time of War". ''New England Journal of History'' (2013) 69#1/2 pp. 1–18.

External links

*

Churchill & The Norway Debate – UK Parliament Living Heritage

{{Clement Attlee, state=collapsed

1940 in politics

1940 in the United Kingdom

Clement Attlee

Neville Chamberlain

Winston Churchill

Debates in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

House of Commons of the United Kingdom

May 1940 in Europe

Norwegian campaign

United Kingdom in World War II

May 1940 in the United Kingdom

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous  Once Germany had rapidly overrun Poland in September 1939, there was a sustained period of military inactivity for over six months dubbed the "

Once Germany had rapidly overrun Poland in September 1939, there was a sustained period of military inactivity for over six months dubbed the " Chamberlain began by reminding the House of his statement on Thursday, 2 May, five days earlier, when it was known that British forces had been withdrawn from

Chamberlain began by reminding the House of his statement on Thursday, 2 May, five days earlier, when it was known that British forces had been withdrawn from  Chamberlain had announced additional powers being granted to Churchill which amounted to him having direction of the Chiefs of Staff. Attlee seized on this as an example of government incompetence, though without blaming Churchill, by saying:

Attlee struck a theme here that would recur throughout the debate – that the government was incompetent but not Churchill himself, even though he was part of it, as he had suffered from what Jenkins calls a misdirection of his talents. Jenkins remarks that Churchill's potential had not been fully utilised and, most importantly, he was clean of the stain of appeasement.

Chamberlain had been heckled during his speech for having "missed the bus" and he made his case worse by desperately trying, and failing, to excuse his use of that expression a month earlier. In doing so, he provided Attlee with an opportunity. During the conclusion of his response, Attlee said:

Attlee's closing words were a direct attack on all Conservative members, blaming them for shoring up ministers whom they knew to be failures:

Leo Amery said later that Attlee's restraint, in not calling for a division of the House (i.e., a vote), was of greater consequence than all his criticisms because, Amery believed, it made it much easier for Conservative members to be influenced by the debate's opening day.

Chamberlain had announced additional powers being granted to Churchill which amounted to him having direction of the Chiefs of Staff. Attlee seized on this as an example of government incompetence, though without blaming Churchill, by saying:

Attlee struck a theme here that would recur throughout the debate – that the government was incompetent but not Churchill himself, even though he was part of it, as he had suffered from what Jenkins calls a misdirection of his talents. Jenkins remarks that Churchill's potential had not been fully utilised and, most importantly, he was clean of the stain of appeasement.

Chamberlain had been heckled during his speech for having "missed the bus" and he made his case worse by desperately trying, and failing, to excuse his use of that expression a month earlier. In doing so, he provided Attlee with an opportunity. During the conclusion of his response, Attlee said:

Attlee's closing words were a direct attack on all Conservative members, blaming them for shoring up ministers whom they knew to be failures:

Leo Amery said later that Attlee's restraint, in not calling for a division of the House (i.e., a vote), was of greater consequence than all his criticisms because, Amery believed, it made it much easier for Conservative members to be influenced by the debate's opening day.

When Bellenger sat down, it was 20:03 and the Deputy Speaker, Dennis Herbert, called on

When Bellenger sat down, it was 20:03 and the Deputy Speaker, Dennis Herbert, called on  Lloyd George had been prime minister during the last two years of the First World War. He was now 77, and it was to be his last major contribution to debate in the House in which he had sat for 50 years. There was personal animosity between Lloyd George and Chamberlain. The latter's appeal to friends gave Lloyd George the opportunity for retribution. First, he attacked the conduct of the campaign and began by dismissing Hoare's entire speech in a single sentence:

Lloyd George then began his main attack on the government by focusing on the lack of planning and preparation:

Emphasising the gravity of the situation, he argued that Britain was in the worst position strategically that it had ever been as a result of foreign policy failures, which he began to review from the 1938

Lloyd George had been prime minister during the last two years of the First World War. He was now 77, and it was to be his last major contribution to debate in the House in which he had sat for 50 years. There was personal animosity between Lloyd George and Chamberlain. The latter's appeal to friends gave Lloyd George the opportunity for retribution. First, he attacked the conduct of the campaign and began by dismissing Hoare's entire speech in a single sentence:

Lloyd George then began his main attack on the government by focusing on the lack of planning and preparation:

Emphasising the gravity of the situation, he argued that Britain was in the worst position strategically that it had ever been as a result of foreign policy failures, which he began to review from the 1938  Churchill was called to speak at 22:11, the first time in eleven years that he had wound up a debate on behalf of the government. Many members believed that it was the most difficult speech of his career because he had to defend a reverse without damaging his own prestige. It was widely felt that he achieved it because, as Nicolson described it, he said not one word against Chamberlain's government and yet, by means of his manner and his skill as an orator, he created the impression of being nothing to do with them.

The first part of Churchill's speech was, as he said it would be, about the Norwegian campaign. The second part, concerning the vote of censure which he called a new issue that had been sprung upon the House at five o'clock, he said he would deal with in due course.

Churchill proceeded to defend the conduct of the Norwegian campaign with some robustness, although there were several omissions such as his insistence that Narvik be blocked off with a minefield. He explained that even the successful use of the battleship at Narvik had put her at risk from many hazards. Had any come to pass, the operation, now hailed as an example of what should have been done elsewhere, would have been condemned as foolhardy:

As for the lack of action at Trondheim, Churchill said it was not because of any perceived danger, but because it was thought unnecessary. He reminded the House that the campaign continued in northern Norway, at Narvik in particular but he would not be drawn into giving any predictions about it. Instead, he attacked the government's critics by deploring what he called a cataract of unworthy suggestions and actual falsehoods during the last few days:

Churchill then had to deal with interruptions and an intervention by Arthur Greenwood who wanted to know if the war cabinet had delayed action at Trondheim. Churchill denied that and advised Greenwood to dismiss such delusions. Soon afterwards, he reacted to a comment by Labour MP

Churchill was called to speak at 22:11, the first time in eleven years that he had wound up a debate on behalf of the government. Many members believed that it was the most difficult speech of his career because he had to defend a reverse without damaging his own prestige. It was widely felt that he achieved it because, as Nicolson described it, he said not one word against Chamberlain's government and yet, by means of his manner and his skill as an orator, he created the impression of being nothing to do with them.

The first part of Churchill's speech was, as he said it would be, about the Norwegian campaign. The second part, concerning the vote of censure which he called a new issue that had been sprung upon the House at five o'clock, he said he would deal with in due course.

Churchill proceeded to defend the conduct of the Norwegian campaign with some robustness, although there were several omissions such as his insistence that Narvik be blocked off with a minefield. He explained that even the successful use of the battleship at Narvik had put her at risk from many hazards. Had any come to pass, the operation, now hailed as an example of what should have been done elsewhere, would have been condemned as foolhardy:

As for the lack of action at Trondheim, Churchill said it was not because of any perceived danger, but because it was thought unnecessary. He reminded the House that the campaign continued in northern Norway, at Narvik in particular but he would not be drawn into giving any predictions about it. Instead, he attacked the government's critics by deploring what he called a cataract of unworthy suggestions and actual falsehoods during the last few days:

Churchill then had to deal with interruptions and an intervention by Arthur Greenwood who wanted to know if the war cabinet had delayed action at Trondheim. Churchill denied that and advised Greenwood to dismiss such delusions. Soon afterwards, he reacted to a comment by Labour MP