Nahda Bint Uman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nahda (, meaning 'the Awakening'), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Arab Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in

/ref> The renaissance itself started simultaneously in both Egypt and Levant, the Levant. Due to their differing backgrounds, the aspects that they focused on differed as well; with Egypt focused on the political aspects of the Islamic world while the Levant focused on the more cultural aspects. The concepts were not exclusive by region however, and this distinction blurred as the renaissance progressed.

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arab world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arab world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician Francis Marrash (1835 or 29 June 1836 – 1874) had traveled throughout West Asia and France in his youth. He expressed ideas of political and social reforms in ''Ghabat al-haqq'' (first published 1865), highlighting the need of the Arabs for two things above all: modern schools and patriotism "free from religious considerations". In 1870, when distinguishing the notion of fatherland from that of nation and applying the latter to the

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician Francis Marrash (1835 or 29 June 1836 – 1874) had traveled throughout West Asia and France in his youth. He expressed ideas of political and social reforms in ''Ghabat al-haqq'' (first published 1865), highlighting the need of the Arabs for two things above all: modern schools and patriotism "free from religious considerations". In 1870, when distinguishing the notion of fatherland from that of nation and applying the latter to the

A group of young writers formed ''

A group of young writers formed ''

https://sqawoa.com/archives/47555]

Plain talk

– by Mursi Saad ed-Din, in ''

Tahtawi in Paris

– by Peter Gran, in ''

France as a Role Model

– by Barbara Winckler {{Syria topics Culture of Egypt Islamic culture Islam and politics Arab culture Arab nationalism

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

-populated regions of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, notably in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

, Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, and Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

, during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century.

In traditional scholarship, the Nahda is seen as connected to the cultural shock brought on by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's invasion of Egypt in 1798, and the reformist drive of subsequent rulers such as Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali (4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849) was the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Albanians, Albanian viceroy and governor who became the ''de facto'' ruler of History of Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty, Egypt from 1805 to 1848, widely consi ...

. However, more recent scholarship has shown the Nahda's cultural reform program to have been as "autogenetic" as it was Western-inspired, having been linked to the Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

—the period of political reform within the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

which brought a constitutional order to Ottoman politics and engendered a new political class—as well as the later Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908; ) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress, an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II ...

, allowing proliferation of the press and other publications and internal changes in political economy and communal reformations in Egypt and Syria and Lebanon. Stephen Sheehi, Foundations of Modern Arab Identity

''Foundations of Modern Arab Identity'' (Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2004) is a book-length study of the Nahda, or Arab Renaissance, by Arab American scholar Stephen Sheehi, which critically engages the intellectual struggl ...

. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 200/ref> The renaissance itself started simultaneously in both Egypt and Levant, the Levant. Due to their differing backgrounds, the aspects that they focused on differed as well; with Egypt focused on the political aspects of the Islamic world while the Levant focused on the more cultural aspects. The concepts were not exclusive by region however, and this distinction blurred as the renaissance progressed.

Early figures

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi

Egyptian scholar Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (1801–1873) is widely seen as the pioneering figure of the Nahda. He was sent to Paris in 1826 by Muhammad Ali's government to study Western sciences and educational methods, although originally to serve asImam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

for the Egyptian cadets training at the Paris military academy. He came to hold a very positive view of French society, although not without criticisms. Learning French, he began translating important scientific and cultural works into Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

. He also witnessed the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first of 1789–99. It led to the overthrow of King Cha ...

of 1830, against Charles X Charles X may refer to:

* Charles X of France (1757–1836)

* Charles X Gustav (1622–1660), King of Sweden

* Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon (1523–1590), recognized as Charles X of France but renounced the royal title

See also

*

* King Charle ...

, but was careful in commenting on the matter in his reports to Muhammad Ali. His political views, originally influenced by the conservative Islamic teachings of al-Azhar

Al-Azhar Mosque (), known in Egypt simply as al-Azhar, is a mosque in Cairo, Egypt in the historic Islamic core of the city. Commissioned as the new capital of the Fatimid Caliphate in 970, it was the first mosque established in a city that ...

university, changed on a number of matters, and he came to advocate parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of the legisl ...

and women's education.

After five years in France, he then returned to Egypt to implement the philosophy of reform he had developed there, summarizing his views in the book ''Takhlis al-Ibriz fi Talkhis Bariz'' (sometimes translated as ''The Quintessence of Paris''), published in 1834. It is written in rhymed prose Rhymed prose is a literary form and literary genre, written in Meter (poetry), unmetrical rhymes. This form has been known in many different cultures. In some cases the rhymed prose is a distinctive, well-defined style of writing. In modern literar ...

, and describes France and Europe from an Egyptian Muslim viewpoint. Tahtawi's suggestion was that the Egypt and the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

had much to learn from Europe, and he generally embraced Western society, but also held that reforms should be adapted to the values of Islamic culture

Islamic cultures or Muslim cultures refers to the historic cultural practices that developed among the various peoples living in the Muslim world. These practices, while not always religious in nature, are generally influenced by aspects of Islam ...

. This brand of self-confident but open-minded modernism came to be the defining creed of the Nahda.

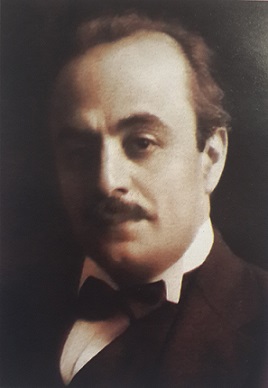

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arab world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (born 1805 or 1806 as Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; died 1887) grew up in present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christian by birth, he later lived in major cities of the Arab world, where he had his career. He converted to Protestantism during the nearly two decades that he lived and worked in Cairo, present-day Egypt, from 1825 to 1848. He also spent time on the island of Malta. Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen. He next moved to Paris, France, for two years in the early 1850s, where he wrote and published some of his most important work.

Later in the 1850s Faris moved to Tunisia, where in 1860 he converted to Islam, taking the first name Ahmad. Moving to Istanbul later that year to work as a translator at the request of the Ottoman government, Faris also founded an Arabic-language newspaper. It was supported by the Ottomans, Egypt and Tunisia, publishing until the late 1880s.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey. Shidyaq is considered to be one of the founding fathers of modern Arabic literature; he wrote most of his fiction in his younger years.

Butrus al-Bustani

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese

Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1893) was born to a Lebanese Maronite Christian

Lebanese Maronite Christians (; ) refers to Lebanese people who are members of the Maronite Church in Lebanon, the largest Christian body in the country. The Lebanese Maronite population is concentrated mainly in Mount Lebanon and East Beir ...

family in the village of Dibbiye

Dibbiyeh or Debbiyeh () is a Lebanese village in the Iqlim al-Kharrub part of the Chouf district mountains, located roughly 30 kilometers south of Beirut, Lebanon. It is considered to be a midway point between the capital and the rest of Mou ...

in the Chouf

Chouf (also spelled Shouf, Shuf or Chuf; ) is a historic region of Lebanon, as well as an administrative district in the governorate ( muhafazat) of Mount Lebanon.

Geography

Located south-east of Beirut, the region comprises a narrow coastal stri ...

region, in January 1819. A polyglot, educator, and activist, Al-Bustani was a tour de force in the Nahda centered in mid-nineteenth century Beirut. Having been influenced by American missionaries, he converted to Protestantism, becoming a leader in the native Protestant church. Initially, he taught in the schools of the Protestant missionaries at 'Abey and was a central figure in the missionaries' translation of the Bible into Arabic. Despite his close ties to the Americans, Al-Bustani increasingly became independent, eventually breaking away from them.

After the bloody 1860 Druze–Maronite conflict

The 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus, also known as the 1860 Christian–Druze war, was a civil conflict in Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, Mount Lebanon during Ottoman Empire, Ottoman rule in 1860–1861 fought mainly between the lo ...

and the increasing entrenchment of confessionalism, Al-Bustani founded the National School or Al-Madrasa Al-Wataniyya in 1863, on secular principles. This school employed the leading Nahda "pioneers" of Beirut and graduated a generation of Nahda thinkers. At the same time, he compiled and published several school textbooks and dictionaries; leading him to becoming known famously as the Master of the Arabic Renaissance.

In the social, national and political spheres, Al-Bustani founded associations with a view to forming a national elite and launched a series of appeals for unity in his magazine ''Nafir Suriyya''.

In the cultural/scientific fields, he published a fortnightly review and two daily newspapers. In addition, he began work, together with Drs. Eli Smith

Eli Smith (September 13, 1801 – January 11, 1857) was an American Protestant missionary and scholar.

Biography

Smith was born in Northford, Connecticut, to Eli and Polly (née Whitney) Smith. He graduated from Yale College in 1821 and from A ...

and Cornelius Van Dyck

Cornelius Van Alen Van Dyck, M.D. (August 13, 1818 – November 13, 1895) was an American missionary physician, teacher and translator of the Protestant Bible into Arabic.Syrian nationalism

Syrian nationalism (), also known as pan-Syrian nationalism or pan-Syrianism (), refers to the nationalism of the region of Syria, as a cultural or political entity known as " Greater Syria," known in Arabic as '' Bilād ash-Shām'' ().

Syrian ...

(not to be confused with Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism () is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, the Arabic language and Arabic literatur ...

).

Stephen Sheehi states that Al-Bustani's "importance does not lie in his prognosis of Arab culture or his national pride. Nor is his advocacy of discriminatingly adopting Western knowledge and technology to "awaken" the Arabs' inherent ability for cultural success,(najah), unique among his generation. Rather, his contribution lies in the act of elocution. That is, his writing articulates a specific formula for native progress that expresses a synthetic vision of the matrix of modernity within Ottoman Syria." Stephen Sheehi, "Butrus al-Bustani: Syria's Ideologue of the Age," in "The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers, and Identity", Adel Bishara (ed.). London: Routledge, 2011, pp. 57–78

Bustani's son Salim

Salim, Saleem or Selim may refer to:

People

*Salim (name), or Saleem or Salem or Selim, a name of Arabic origin

**Salim (poet) (1800–1866), Kurdish poet

**Saleem (playwright), Palestinian-American gay Muslim playwright, actor, DJ, and dancer

* ...

was also part of the movement.

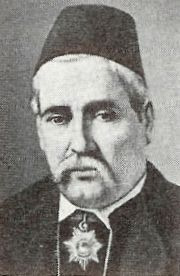

Hayreddin Pasha

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the

Hayreddin Pasha al-Tunsi (1820–1890) had made his way to Ottoman Tunisia as a slave, where he rose through the ranks of the government of Ahmad Bey, the modernizing ruler of Tunisia. He soon was made responsible for diplomatic missions to the Ottoman Empire and the countries of Europe, bringing him into contact with Western ideals, as well as with the Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

reforms of the Ottoman Empire. He served as Prime Minister of Tunisia from 1859 until 1882. In this period, he was a major force of modernization in Tunisia.

In numerous writings, he envisioned a seamless blending of Islamic tradition with Western modernization. Basing his beliefs on European Enlightenment writings and Arabic political thought, his main concern was with preserving the autonomy of the Tunisian people in particular, and Muslim peoples in general. In this quest, he ended up bringing forth what amounted to the earliest example of Muslim constitutionalism. His modernizing theories have had an enormous influence on Tunisian and Ottoman thought.

Francis Marrash

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician Francis Marrash (1835 or 29 June 1836 – 1874) had traveled throughout West Asia and France in his youth. He expressed ideas of political and social reforms in ''Ghabat al-haqq'' (first published 1865), highlighting the need of the Arabs for two things above all: modern schools and patriotism "free from religious considerations". In 1870, when distinguishing the notion of fatherland from that of nation and applying the latter to the

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician Francis Marrash (1835 or 29 June 1836 – 1874) had traveled throughout West Asia and France in his youth. He expressed ideas of political and social reforms in ''Ghabat al-haqq'' (first published 1865), highlighting the need of the Arabs for two things above all: modern schools and patriotism "free from religious considerations". In 1870, when distinguishing the notion of fatherland from that of nation and applying the latter to the region of Syria

Syria, ( or ''Shaam'') also known as Greater Syria or Syria-Palestine, is a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in West Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. The region boundaries have changed throughout history. Howe ...

, Marrash pointed to the role played by language, among other factors, in counterbalancing religious and sectarian differences, and thus, in defining national identity.

Marrash has been considered the first truly cosmopolitan Arab intellectual and writer of modern times, having adhered to and defended the principles of the French Revolution in his own works, implicitly criticizing Ottoman rule in West Asia and North Africa.

He also tried to introduce "a revolution in diction, themes, metaphor and imagery in modern Arabic poetry". His use of conventional diction for new ideas is considered to have marked the rise of a new stage in Arabic poetry which was carried on by the Mahjar

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and ...

is.

Politics and society

Proponents of the Nahda typically supported reforms. While al-Bustani and al-Shidyaq "advocated reform without revolution", the "trend of thought advocated by Francis Marrash ..and Adib Ishaq" (1856–1884) was "radical and revolutionary. In 1876, theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

promulgated a constitution, as the crowning accomplishment of the Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

reforms (1839–1876) and inaugurating the Empire's First Constitutional Era

The First Constitutional Era (; ) of the Ottoman Empire was the period of constitutional monarchy from the promulgation of the Ottoman constitution of 1876 (, , meaning ' Basic Law' or 'Fundamental Law' in Ottoman Turkish), written by members ...

. It was inspired by European methods of government and designed to bring the Empire back on level with the Western powers. The constitution was opposed by the Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

, whose powers it checked, but had vast symbolic and political importance.

The introduction of parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of the legisl ...

also created a political class in the Ottoman-controlled provinces, from which later emerged a liberal nationalist elite that would spearhead the several nationalist movements, in particular Egyptian nationalism

Egyptian nationalism is based on Egyptians and Egyptian culture. Egyptian nationalism has typically been a civic nationalism that has emphasized the unity of Egyptians regardless of their ethnicity or religion. Egyptian nationalism first manife ...

. Egyptian nationalism was non-Arab, emphasising ethnic Egyptian identity and history in response to European colonialism and the Turkish occupation of Egypt. This was paralleled by the rise of the Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

in the central Ottoman provinces and administration. The resentment towards Turkish rule fused with protests against the Sultan's autocracy, and the largely secular concepts of Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism () is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, the Arabic language and Arabic literatur ...

rose as a cultural response to the Ottoman Caliphate

The Ottoman Caliphate () was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty, rulers of the Ottoman Empire, to be the caliphs of Islam during the Late Middle Ages, late medieval and Early Modern period, early modern era.

Ottoman rulers ...

's claims of religious legitimacy. Various Arab nationalist secret societies rose in the years prior to World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, such as al-Fatat

Al-Fatat (, al-Fatat) or the Young Arab Society (, Jam’iyat al-’Arabiya al-Fatat) was an underground Arab nationalist organization in the Ottoman Empire. Its aims were to gain independence and unify various Arab territories that were then und ...

and al-ʽAhd, which was military-based.

This was complemented by the rise of other national movements, including Syrian nationalism

Syrian nationalism (), also known as pan-Syrian nationalism or pan-Syrianism (), refers to the nationalism of the region of Syria, as a cultural or political entity known as " Greater Syria," known in Arabic as '' Bilād ash-Shām'' ().

Syrian ...

, which like Egyptian nationalism was in some of its manifestations essentially non-Arabist and connected to the concept of the region of Syria

Syria, ( or ''Shaam'') also known as Greater Syria or Syria-Palestine, is a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in West Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. The region boundaries have changed throughout history. Howe ...

. The main other example of the late ''al-Nahda'' era is the emerging Palestinian nationalism

Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people that espouses Palestinian self-determination, self-determination and sovereignty over the region of Palestine.de Waart, 1994p. 223 Referencing Article 9 of ''The Pales ...

, which was set apart from Syrian nationalism by Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

immigration to Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

and the resulting sense of Palestinian particularism.

Women's rights

Al-Shidyaq defendedwomen's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

in ''Leg Over Leg

''Leg over Leg'' () is a book by Ahmad Faris Shidyaq, considered one of the founders of modern Arabic literature. Detailing the life of 'the Fariyaq', the alter ego of the author, offering commentary on intellectual and social issues, it is describ ...

'', which was published as early as 1855 in Paris. Esther Moyal

Esther Moyal (née Lazari or al-Azharī; 1874, Beirut – 1948, Jaffa) was a History of the Jews in Lebanon, Lebanese Jewish journalist, writer and Women's rights, women's rights activist. She has been described as a key intellectual in the 20th c ...

, a Lebanese Jewish author, wrote extensively on women's rights in her magazine ''The Family'' throughout the 1890s.

Religion

In the religious field,Jamal al-Din al-Afghani

Sayyid Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī (Pashto/), also known as Jamāl ad-Dīn Asadābādī () and commonly known as Al-Afghani (1838/1839 – 9 March 1897), was an Iranian political activist and Islamic ideologist who travelled throughout the Mus ...

(1839–1897) gave Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

a modernist reinterpretation and fused adherence to the faith with an anti-colonial doctrine that preached Pan-Islamic

Pan-Islamism () is a political movement which advocates the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Historically, after Ottomanism, which aimed at ...

solidarity in the face of European pressures. He also favored the replacement of authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

monarchies with representative rule, and denounced what he perceived as the dogmatism, stagnation and corruption of the Islam of his age. He claimed that tradition (''taqlid

''Taqlid'' (, " imitation") is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs ''taqlid'' is termed ''muqallid''. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on context and age. Cla ...

'', تقليد) had stifled Islamic debate and repressed the correct practices of the faith. Al-Afghani's case for a redefinition of old interpretations of Islam, and his bold attacks on traditional religion, would become vastly influential with the fall of the Ottoman Caliphate

The Ottoman Caliphate () was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty, rulers of the Ottoman Empire, to be the caliphs of Islam during the Late Middle Ages, late medieval and Early Modern period, early modern era.

Ottoman rulers ...

in 1924. This created a void in the religious doctrine and social structure of Islamic communities which had been only temporarily reinstated by Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

in an effort to bolster universal Muslim support, suddenly vanished. It forced Muslims to look for new interpretations of the faith, and to re-examine widely held dogma; exactly what al-Afghani had urged them to do decades earlier.

Al-Afghani influenced many, but greatest among his followers is undoubtedly his student Muhammad Abduh

Muḥammad ʿAbduh (also spelled Mohammed Abduh; ; 1849 – 11 July 1905) was an Egyptian Islamic scholar, judge, and Grand Mufti of Egypt. He was a central figure of the Arab Nahḍa and Islamic Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th ce ...

(1849–1905), with whom he started a short-lived Islamic revolutionary journal, ''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa

''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa'' (, ) was an Islamic revolutionary journal founded by Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī. Despite only running from 13 March 1884 to October 1884, it was one of the first and most important publications of the ' ...

'', and whose teachings would play a similarly important role in the reform of the practice of Islam. Like al-Afghani, Abduh accused traditionalist Islamic authorities of moral and intellectual corruption, and of imposing a doctrinaire form of Islam on the ummah

' (; ) is an Arabic word meaning Muslim identity, nation, religious community, or the concept of a Commonwealth of the Muslim Believers ( '). It is a synonym for ' (, lit. 'the Islamic nation'); it is commonly used to mean the collective com ...

, that had hindered correct applications of the faith. He therefore advocated that Muslims should return to the "true" Islam practiced by the ancient Caliphs, which he held had been both rational and divinely inspired. Applying the original message of the Islamic prophet

Prophets in Islam () are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets are categorized as messengers (; sing. , ), those who transmit divine revelation, mos ...

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

with no interference of tradition or the faulty interpretations of his followers, would automatically create the just society ordained by God in the Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

, and so empower the Muslim world to stand against colonization and injustices.

Among the students of Abduh were Syrian Islamic scholar and reformer Rashid Rida

Sayyid Muhammad Rashīd Rida Al-Hussaini (; 1865 – 22 August 1935) was an Ulama, Islamic scholar, Islah, reformer, theologian and Islamic revival, revivalist. An early Salafi movement, Salafist, Rida called for the revival of hadith studies and ...

(1865–1935), who continued his legacy, and expanded on the concept of just Islamic government. His theses on how an Islamic state

The Islamic State (IS), also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Daesh, is a transnational Salafi jihadism, Salafi jihadist organization and unrecognized quasi-state. IS ...

should be organized remain influential among modern-day Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ('' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar, Imam and schoolteacher Hassan al-Banna in 1928. Al-Banna's teachings s ...

.

Christians

Arab Christians

Arab Christians () are the Arabs who adhere to Christianity. The number of Arab Christians who live in the Middle East was estimated in 2012 to be between 10 and 15 million. Arab Christian communities can be found throughout the Arab world, bu ...

played a crucial role in the Nahda movement. Their status as an educated minority enabled them to significantly influence and contribute to the fields of literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, politics, business, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, music, theatre and cinema, medicine, and science. Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

, Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, and Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

were the main centers of the renaissance, which led to the establishment of schools, universities, theaters and printing presses there. This awakening led to the emergence of a politically active movement known as the "association" that was accompanied by the birth of Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism () is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, the Arabic language and Arabic literatur ...

and the demand for reformation in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. This led to the calling of the establishment of modern states based on Europe. It was during this stage that the first compound of the Arabic language was introduced along with the printing of it in letters, and later the movement influenced the fields of music, sculpture, history, humanities, economics and human rights.

This cultural renaissance during the late Ottoman rule was a quantum leap for Arabs in the post-industrial revolution, and is not limited to the individual fields of cultural renaissance in the nineteenth century, as the Nahda only extended to include the spectrum of society and the fields as a whole. Christian colleges (accepting of all faiths) like Saint Joseph University

Saint Joseph University of Beirut (; French: ''Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth'', commonly known as USJ) is a private Catholic research university in Beirut, Lebanon, founded in 1875 by French Jesuit missionaries and subsidized by the Go ...

, the Syrian Protestant College

The American University of Beirut (AUB; ) is a private, non-sectarian, and independent university chartered in New York with its main campus in Beirut, Lebanon. AUB is governed by a private, autonomous board of trustees and offers programs lead ...

(which later became the American University of Beirut) and Al-Hikma University in Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

amongst others played a prominent role in the development of Arab culture.Lattouf, 2004, p. 70 It is agreed amongst historians the importance the roles played by the Arab Christians

Arab Christians () are the Arabs who adhere to Christianity. The number of Arab Christians who live in the Middle East was estimated in 2012 to be between 10 and 15 million. Arab Christian communities can be found throughout the Arab world, bu ...

in this renaissance, and their role in the prosperity through participation in the diaspora. Given this role in politics and culture, Ottoman ministers began to include them in their governments. In the economic sphere, a number of Christian families like the Greek Orthodox Sursock family

The Sursock family (also spelled Sursuq) is a Greek Orthodox Christian family from Lebanon, and used to be one of the most important families of Beirut. Having originated in Constantinople during the Byzantine Empire, the family has lived in Bei ...

became prominent. Thus, the Nahda led the Muslims and Christians to a cultural renaissance and national general despotism. This solidified Arab Christians

Arab Christians () are the Arabs who adhere to Christianity. The number of Arab Christians who live in the Middle East was estimated in 2012 to be between 10 and 15 million. Arab Christian communities can be found throughout the Arab world, bu ...

as one of the pillars of the region and not a minority on the fringes.

The Mahjar

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and ...

(one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a literary movement that preceded the Nahda movement. It was started by Christian Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America from Lebanon, Syria and Palestine at the turn of the 20th century. The Pen League was the first Arabic-language literary society

A literary society is a group of people interested in literature. In the modern sense, this refers to a society that wants to promote one genre of writing or a specific author. Modern literary societies typically promote research, publish newslet ...

in North America, formed initially by Syrians Nasib Arida

Nasib Arida (, ; 1887–1946) was a Syrian-born poet and writer of the Mahjar movement and a founding member of the New York Pen League.

Life

Arida was born in Homs to a Syrian Greek Orthodox family where he received his education until h ...

and Abd al-Masih Haddad. Members of the Pen League included: Kahlil Gibran

Gibran Khalil Gibran (January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931), usually referred to in English as Kahlil Gibran, was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and Visual arts, visual artist; he was also considered a philosopher, although he himself reject ...

, Elia Abu Madi

Elia Abu Madi (also known as Elia D. Madey; 'Lebanese Arabic Transliteration: , .) (May 15, 1890 – November 23, 1957) was a Lebanon, Lebanese-born American poet.

Early life

Abu Madi was born in the village of Al-Muhaydithah, now part o ...

, Mikhail Naimy

Mikha'il Nu'ayma (, ; US legal name: Michael Joseph Naimy), better known in English by his pen name Mikhail Naimy (October 17, 1889 – February 28, 1988), was a Lebanese poet, novelist, and philosopher, famous for his spiritual writings, notabl ...

, and Ameen Rihani

Ameen Rihani (Amīn Fāris Anṭūn ar-Rīḥānī; / ALA-LC: ''Amīn ar-Rīḥānī''; November 24, 1876 – September 13, 1940) was a Lebanese-American writer, intellectual and political activist. He was also a major figure in the ''mah ...

. Eight out of the ten members were Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

and two were Maronite

Maronites (; ) are a Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant (particularly Lebanon) whose members belong to the Maronite Church. The largest concentration has traditionally re ...

Christians.

In the early 20th century, many prominent Arab nationalists

Arab nationalism () is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, the Arabic language and Arabic literatur ...

were Christians, like the Syrian

Syrians () are the majority inhabitants of Syria, indigenous to the Levant, most of whom have Arabic, especially its Levantine and Mesopotamian dialects, as a mother tongue. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend ...

intellectual Constantin Zureiq

Constantin Zureiq (; ; April 18, 1909 – August 11, 2000) was a prominent Syrian intellectual who was one of the first to pioneer and express the importance of Arab nationalism. He stressed the urgent need to transform stagnant Arab society u ...

, Ba'athism

Ba'athism, also spelled Baathism, is an Arab nationalist ideology which advocates the establishment of a unified Arab state through the rule of a Ba'athist vanguard party operating under a revolutionary socialist framework. The ideology i ...

founder Michel Aflaq

Michel Aflaq (, ; 9 January 1910 – 23 June 1989) was a Syrian philosopher, sociology, sociologist and Arab nationalism, Arab nationalist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of Ba'athism and its political movement; he ...

, and Jurji Zaydan

Jurji Zaydan (, ; December 14, 1861 – July 21, 1914) was a prolific Lebanese novelist, journalist, editor and teacher, most noted for his creation of the magazine '' Al-Hilal'', which he used to serialize his twenty three historical novels.

H ...

, who was reputed to be the first Arab nationalist. Khalil al-Sakakini

Khalil Sakakini (; 23 January 1878 – 13 August 1953) was a Palestinian teacher, scholar, poet, and Arab nationalist.

Biography

Sakakini was born into a Palestinian Christian Orthodox family in Jerusalem in the Ottoman Empire on 23 Januar ...

, a prominent Palestinian Jerusalemite

Jerusalem's population size and composition has shifted many times over its 5,000 year history.

Most population data pre-1905 is based on estimates, often from foreign travellers or organisations, since previous census data usually covered w ...

, was Arab Orthodox, as was George Antonius

George Habib Antonius, Order of the British Empire, CBE (hon.) (; October 19, 1891May 21, 1942) was a Lebanese people, Lebanese author and diplomat who settled in Jerusalem. He was one of the first historians of Arab nationalism. Born in Deir a ...

, Lebanese author of ''The Arab Awakening

''The Arab Awakening'' is a 1938 book by George Antonius, published in London by Hamish Hamilton. It is viewed as the foundational textbook of the history of modern Arab nationalism. According to Martin Kramer, ''The Arab Awakening'' "became the p ...

.''

Shia Islam

Shi'a

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor ( caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community ( imam). However, his right is understoo ...

scholars also contributed to the renaissance movement, including the linguist Ahmad Rida

Sheikh Ahmad Rida (also transliterated as Ahmad Reda) (1872–1953) () was a Lebanese people, Lebanese Arabic language, linguist, writer and politician. A key figure of the Arab Renaissance (known as al-Nahda), he compiled the modern monolingual ...

and his son-in-law the historian Muhammad Jaber Al Safa

Muhammad Jaber Āl Safa (also spelled Jabir Al Safa) (1875–1945) () was a historian, writer and politician from Jabal Amel (in modern-day Lebanon), known for his founding role in the anti-colonialist Arab nationalist movement in the turn-of-the ...

. Important political reforms took place simultaneously also in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and Shi'a religious beliefs saw important developments with the systematization of a religious hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Ancient Greek, Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy ...

. A wave of political reform followed, with the constitutional movement in Iran to some extent paralleling the Egyptian Nahda reforms.

Science

Many student missions from Egypt went to Europe in the early 19th century to study arts and sciences at European universities and acquire technical skills. Arabic-language magazines began to publish articles of scientific vulgarization.Modern literature

Through the 19th century and early 20th centuries, a number of new developments in Arabic literature started to emerge, initially sticking closely to the classical forms, but addressing modern themes and the challenges faced by the Arab world in the modern era. Francis Marrash was influential in introducing French romanticism in the Arab world, especially through his use of poetic prose and prose poetry, of which his writings were the first examples in modern Arabic literature, according toSalma Khadra Jayyusi

Salma Khadra Jayyusi (; 16 April 1925 – 20 April 2023) was a Palestinian poet, writer, translator and anthologist. She was the founder and director of the Project of Translation from Arabic (PROTA), which aims to provide translation of Arabic ...

and Shmuel Moreh

Shmuel Moreh (; December 22, 1932 – September 22, 2017) was a professor of Arabic Language and Literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a recipient of the Israel Prize in Middle Eastern studies in 1999. In addition to having written ...

. In Egypt, Ahmad Shawqi

Ahmed Shawqi (, , ; 1868–1932), nicknamed the Prince of Poets ( ''Amīr al-Shu‘arā’''), was an Egyptian poet laureate, linguist, and one of the most famous Arabic literary writers of the modern era in the Arab World.

Life

Shawqi was b ...

(1868–1932), among others, began to explore the limits of the classical qasida, although he remained a clearly neo-classical poet. After him, others, including Hafez Ibrahim

Hafez Ibrahim (, ; 1871–1932) was a well known Egyptian poet of the early 20th century. He was dubbed the "Poet of the Nile", and sometimes the "Poet of the People", for his political commitment to the poor. His poetry took on the concerns o ...

(1871–1932) began to use poetry to explore themes of anticolonialism

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholars of decolon ...

as well as the classical concepts. In 1914, Muhammad Husayn Haykal

Mohammed Hussein Heikal ( ; August 20, 1888 – December 8, 1956) was an Egyptian writer, journalist, politician. He held several cabinet posts, including minister of education.

Life

Haekal was born in Kafr Ghannam, Mansoura, Ad Daqahliyah in ...

(1888–1956) published '' Zaynab'', often considered the first modern Egyptian novel. This novel started a movement of modernizing Arabic fiction.

A group of young writers formed ''

A group of young writers formed ''Al-Madrasa al-Ḥadītha

''Al-Madrasa al-Ḥadītha'' ( or 'The New School') was a Modernism, modernist movement in Arabic literature that began in 1917 in Sultanate of Egypt, Egypt. The movement is associated with the development of the short story in the earlier periods ...

'' ('The New School'), and in 1925 began publishing the weekly literary journal '' Al-Fajr'' (''The Dawn''), which would have a great impact on Arabic literature. The group was especially influenced by 19th-century Russian writers such as Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influenti ...

, Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

and Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works " The Nose", " Viy", "The Overcoat", and " Nevsky Prosp ...

. At about the same time, the Mahjar

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and ...

i poets further contributed from America to the development of the forms available to Arab poets. The most famous of these, Kahlil Gibran

Gibran Khalil Gibran (January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931), usually referred to in English as Kahlil Gibran, was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and Visual arts, visual artist; he was also considered a philosopher, although he himself reject ...

(1883–1931), challenged political and religious institutions with his writing, and was an active member of the Pen League

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arabs, Arab diaspora") was a movement related to neo-romanticism, Romanticism migrant literature, migrant literary literary movement, movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emig ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

from 1920 until his death. Some of the Mahjaris later returned to Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

, such as Mikhail Naimy

Mikha'il Nu'ayma (, ; US legal name: Michael Joseph Naimy), better known in English by his pen name Mikhail Naimy (October 17, 1889 – February 28, 1988), was a Lebanese poet, novelist, and philosopher, famous for his spiritual writings, notabl ...

(1898–1989).

Jurji Zaydan

Jurji Zaydan (, ; December 14, 1861 – July 21, 1914) was a prolific Lebanese novelist, journalist, editor and teacher, most noted for his creation of the magazine '' Al-Hilal'', which he used to serialize his twenty three historical novels.

H ...

(1861–1914) developed the genre of the Arabic historical novel. May Ziadeh

May Elias Ziadeh ( ; , ; 11 February 1886 – 17 October 1941) was a Palestinians, Palestinian-Lebanese people, Lebanese Maronite poet, essayist, and translator, who wrote many different works both in Arabic language, Arabic and in French la ...

(1886–1941) was also a key figure in the early 20th century Arabic literary scene.

Aleppine writer Qustaki al-Himsi

Qustaki al-Himsi (, ; 1858–1941) was a Syrian writer and poet of the Nahda movement (the Arabic renaissance), a prominent figure in the Arabic literature of the 19th and 20th centuries and one of the first reformers of the traditional Arab ...

(1858–1941) is credited with having founded modern Arabic literary criticism

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature's ...

, with one of his works, ''The researcher's source in the science of criticism''.

An example of modern poetry in classical Arabic style with themes of Pan-Arabism

Pan-Arabism () is a Pan-nationalism, pan-nationalist ideology that espouses the unification of all Arabs, Arab people in a single Nation state, nation-state, consisting of all Arab countries of West Asia and North Africa from the Atlantic O ...

is the work of Aziz Pasha Abaza

Aziz Pasha Abaza (, born 13 August 1898 – 11 July 1973) was an Egyptian poet, known in the fields of modern Egyptian literature and Arab literature.

Abaza's poems are preoccupied with Arab unity and Pan-Arabism. His poetry was an inspiratio ...

. He came from Abaza family

The Abaza family (; , or , ; ) is an Egyptians, Egyptian aristocratic family of maternal Abazin, Circassians, Circassian, and paternal Egyptians, Egyptian origins whose historical stronghold is in the Nile Delta.

It has been described as "deep ...

which produced notable Arabic literary figures including Fekry Pasha Abaza

Fekry Pasha Abaza (1895 – 9 February 1979) was an Egyptian journalist and democratic political activist.

Early life and education

Abaza was born in 1895 in the village of Kafr Abu Shehata in the East, Egypt. He was a member of the Abaza Fa ...

, Tharwat Abaza

Tharwat Abaza (28 June 1927 – 17 March 2002) was an Egyptian journalist and novelist. His best-known novel, ''A Man Escaping from Time'', was turned into an Egyptian television series in the late 1960s, and ''A Taste of Fear'', a short story ...

, and Desouky Bek Abaza, among otherhttps://sqawoa.com/archives/47555]

Dissemination of ideas

Newspapers and journals

The firstprinting press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

in the Middle East was in the Monastery of Saint Anthony of Qozhaya in Lebanon and dates back to 1610. It printed books in Syriac and Garshuni

Garshuni or Karshuni (Syriac alphabet: , Arabic alphabet: ) are Arabic writings using the Syriac alphabet. The word "Garshuni", derived from the word "grasha" which literally translates as "pulling", was used by George Kiraz to coin the term " gar ...

(Arabic using the Syriac alphabet). The first printing press with Arabic letters was built in St John's monastery in Khinshara, Lebanon by "Al-Shamas Abdullah Zakher" in 1734. The printing press operated from 1734 till 1899.

In 1821, Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali (4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849) was the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Albanians, Albanian viceroy and governor who became the ''de facto'' ruler of History of Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty, Egypt from 1805 to 1848, widely consi ...

brought the first printing press to Egypt. Modern printing techniques spread rapidly and gave birth to a modern Egyptian press, which brought the reformist trends of the Nahda into contact with the emerging Egyptian middle class of clerks and tradesmen.

In 1855, Rizqallah Hassun

This is a list of some famous Armenians in Syria.

Politics and military

* Sarkis Assadourian (born 1948, Aleppo), former member of Canadian Parliament

* Samuel Der-Yeghiayan (born 1952, Aleppo), United States federal judge, noteworthy for being t ...

(1825–1880) founded the first newspaper written solely in Arabic, ''Mir'at al-ahwal''. The Egyptian newspaper ''Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' (; ), founded on 5 August 1876, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second-oldest after '' Al-Waqa'i' al-Misriyya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majority owned by the Egyptian governm ...

'' founded by Saleem Takla

Saleem Takla (, also spelled Selim Taqla; 1849 – August 8, 1892) was a Lebanese-Ottoman journalist who founded of ''Al-Ahram'' newspaper with his brother Beshara Takla.

Early life and education

Saleem Takla was born in Kfarshima, Lebanon in 184 ...

dates from 1875, and between 1870 and 1900, Beirut alone saw the founding of about 40 new periodicals and 15 newspapers.

Muhammad Abduh

Muḥammad ʿAbduh (also spelled Mohammed Abduh; ; 1849 – 11 July 1905) was an Egyptian Islamic scholar, judge, and Grand Mufti of Egypt. He was a central figure of the Arab Nahḍa and Islamic Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th ce ...

and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī

Sayyid Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī (Pashto/), also known as Jamāl ad-Dīn Asadābādī () and commonly known as Al-Afghani (1838/1839 – 9 March 1897), was an Iranian political activist and Islamic ideologist who travelled throughout the Mus ...

's weekly pan-Islamic

Pan-Islamism () is a political movement which advocates the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Historically, after Ottomanism, which aimed at ...

anti-colonial revolutionary literary magazine ''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa

''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa'' (, ) was an Islamic revolutionary journal founded by Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī. Despite only running from 13 March 1884 to October 1884, it was one of the first and most important publications of the ' ...

'' (''The Firmest Bond'')—though it only ran from March to October 1884 and was banned by British authorities in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

—was circulated widely from Morocco to India and it's considered one of the first and most important publications of the Nahda.

Encyclopedias and dictionaries

The efforts at translating European and American literature led to the modernization of theArabic language

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

. Many scientific and academic terms, as well as words for modern inventions, were incorporated in modern Arabic vocabulary, and new words were coined in accordance with the Arabic root system to cover for others. The development of a modern press ensured that Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

ceased to be used and was replaced entirely by Modern Standard Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic (MWA) is the variety of Standard language, standardized, Literary language, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in some usages al ...

, which is used still today all over the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

.

In the late 19th century, Butrus al-Bustani

Butrus al-Bustani (, ; 1819–1883) was a Lebanese writer and scholar. He was a major figure in the Nahda, the Arab renaissance which began in Ottoman Egypt and had spread to all Arab-populated regions of the Ottoman Empire by the end of the ...

created the first modern Arabic encyclopedia, drawing both on medieval Arab scholars and Western methods of lexicography

Lexicography is the study of lexicons and the art of compiling dictionaries. It is divided into two separate academic disciplines:

* Practical lexicography is the art or craft of compiling, writing and editing dictionaries.

* Theoretical le ...

. Ahmad Rida

Sheikh Ahmad Rida (also transliterated as Ahmad Reda) (1872–1953) () was a Lebanese people, Lebanese Arabic language, linguist, writer and politician. A key figure of the Arab Renaissance (known as al-Nahda), he compiled the modern monolingual ...

(1872–1953) created the first modern dictionary of Arabic, '' Matn al-Lugha''.

Literary salons

Different salons appeared.Maryana Marrash

Maryana bint Fathallah bin Nasrallah Marrash (Arabic: , ; 1848–1919), also known as Maryana al-Marrash or Maryana Marrash al-Halabiyah, was a Syrian writer and poet of the Nahda or the Arab Renaissance. She revived the tradition of lite ...

was the first Arab woman in the nineteenth century to revive the tradition of the literary salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon

A beauty salon or beauty parlor is an establishment that provides Cosmetics, cosmetic treatments for people. Other variations of this type of business include hair salons, spas, day spas, ...

in the Arab world, with the salon she ran in her family home in Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

. The first salon in Cairo was Princess Nazli Fadil

Nazli Zainab Hanim (; 1853 – 28 December 1913) was an Egyptian princess from the dynasty of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha and one of the first women to revive the tradition of the Women's literary salons and societies in the Ar ...

's.

See also

*Mahjar

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

*Albert Hourani

Albert Habib Hourani, ( ''Albart Ḥabīb Ḥūrānī''; 31 March 1915 – 17 January 1993) was a Lebanese British historian, specialising in the history of the Middle East and Middle Eastern studies.

Background and education

Hourani was bo ...

, ''A History of the Arab Peoples'', New York: Warner Books

Grand Central Publishing is a book publishing imprint of Hachette Book Group, originally established in 1970 as Warner Books when Kinney National Company acquired the New York City-based Paperback Library. When Time Warner sold their book publis ...

, 1991. ()

* Ira M. Lapidus

Ira M. Lapidus is an Emeritus Professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic History at The University of California at Berkeley. He is the author of ''A History of Islamic Societies'', and ''Contemporary Islamic Movements in Historical Perspective'', ...

, ''A History of Islamic Societies'', 2nd Ed. Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, 2002.

* Karen Armstrong

Karen Armstrong (born 14 November 1944) is a British author and commentator known for her books on comparative religion. A former Roman Catholic religious sister, she went from a conservative to a more liberal and Christian mysticism, mystical ...

, ''The Battle for God

''The Battle for God: Fundamentalism in Judaism, Christianity and Islam'' is a book by author Karen Armstrong published in 2000 by Knopf/HarperCollins which the ''New York Times'' described as "one of the most penetrating, readable, and prescient ...

'', New York City, 2000.

* Samir Kassir

Samir Kassir (; 5 May 1960 – 2 June 2005) was a Lebanese-Palestinian journalist of '' An-Nahar'' and professor of history at Saint-Joseph University, who was an advocate of democracy and prominent opponent of the Syrian occupation of Lebanon. ...

, ''Considérations sur le malheur arabe'', Paris, 2004.

* Stephen Sheehi, ''Foundations of Modern Arab Identity

''Foundations of Modern Arab Identity'' (Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2004) is a book-length study of the Nahda, or Arab Renaissance, by Arab American scholar Stephen Sheehi, which critically engages the intellectual struggl ...

'', University Press of Florida

The University Press of Florida (UPF) is the scholarly publishing arm of the State University System of Florida, representing Florida's twelve state universities. It is located in Gainesville near the University of Florida, one of the state's maj ...

, 2004.

* Fruma Zachs and Sharon Halevi, ''From Difa Al-Nisa to Masalat Al-Nisa in greater Syria: Readers and writers debate women and their rights, 1858–1900.'' International Journal of Middle East Studies 41, no. 4 (2009): 615 – 633.

External links

Plain talk

– by Mursi Saad ed-Din, in ''

Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' (; ), founded on 5 August 1876, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second-oldest after '' Al-Waqa'i' al-Misriyya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majority owned by the Egyptian governm ...

'' Weekly.

Tahtawi in Paris

– by Peter Gran, in ''

Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' (; ), founded on 5 August 1876, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second-oldest after '' Al-Waqa'i' al-Misriyya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majority owned by the Egyptian governm ...

'' Weekly.

France as a Role Model

– by Barbara Winckler {{Syria topics Culture of Egypt Islamic culture Islam and politics Arab culture Arab nationalism