Māori History on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Māori began with the arrival of

Evidence from genetics, archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the ancestry of Polynesian people stretches all the way back to indigenous peoples of Taiwan. Language-evolution studies and mtDNA evidence suggest that most Pacific populations originated from Taiwanese indigenous peoples around 5,200 years ago. These

Evidence from genetics, archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the ancestry of Polynesian people stretches all the way back to indigenous peoples of Taiwan. Language-evolution studies and mtDNA evidence suggest that most Pacific populations originated from Taiwanese indigenous peoples around 5,200 years ago. These

The earliest period of Māori settlement is known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period. The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct

The earliest period of Māori settlement is known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period. The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct

Te Papa From this period onward, some 32 species of birds became extinct, either through over-predation by humans and the ''kiore'' and (Polynesian Dog) they introduced; repeated burning of the vegetation that changed their habitat; or climate cooling, which appears to have occurred from about 1400–1450. For a short period – less than 200 years – the early Māori diet included an abundance of large birds and fur seals that had never been hunted before. These animals rapidly declined: many, such as the various moa species, the New Zealand swan and the kōhatu shag becoming extinct; while others, such as

The cooling of the climate, confirmed by a detailed tree-ring study near

The cooling of the climate, confirmed by a detailed tree-ring study near

The New Zealand historian, Michael King, describes the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world". Besides a brief offshore skirmish with Abel Tasman in 1642, the first encounter with the outside world took place with Captain Cook's party on his first voyage in 1769, followed by later contact in 1773 and 1777 during the second and third voyages. Cook spent time mapping the islands in 1769 and meeting Māori, particularly in the Marlborough Sounds in 1777. Cook and his crew recorded their impressions of Māori at the time. This early contact proved problematic and sometimes fatal, with some Europeans being cannibalised.

The New Zealand historian, Michael King, describes the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world". Besides a brief offshore skirmish with Abel Tasman in 1642, the first encounter with the outside world took place with Captain Cook's party on his first voyage in 1769, followed by later contact in 1773 and 1777 during the second and third voyages. Cook spent time mapping the islands in 1769 and meeting Māori, particularly in the Marlborough Sounds in 1777. Cook and his crew recorded their impressions of Māori at the time. This early contact proved problematic and sometimes fatal, with some Europeans being cannibalised.

From the 1780s, Māori encountered European and American

From the 1780s, Māori encountered European and American  Contact with Europeans led to a sharing of concepts. The Māori language was first written down by

Contact with Europeans led to a sharing of concepts. The Māori language was first written down by

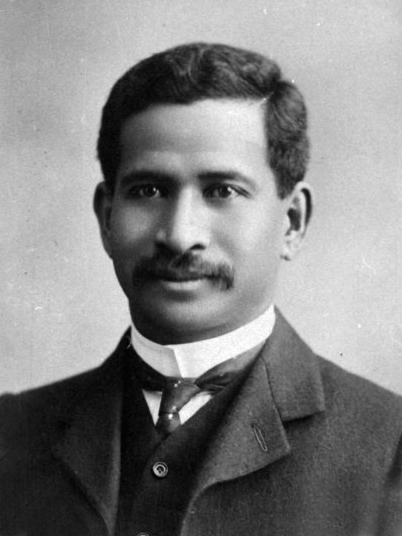

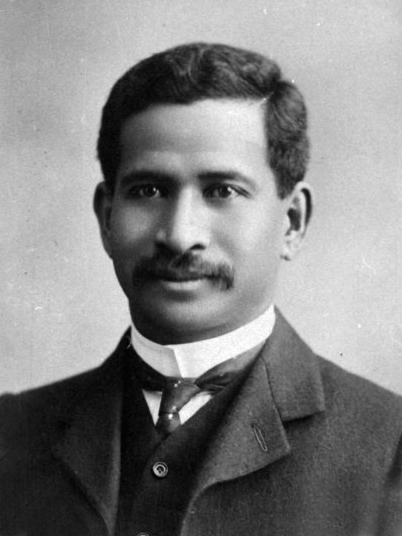

From the late 19th century, successful Māori politicians such as James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata,

From the late 19th century, successful Māori politicians such as James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata,

Since the 1960s, Māoridom has undergone a cultural revival concurrent with activism for social justice and a

Since the 1960s, Māoridom has undergone a cultural revival concurrent with activism for social justice and a

Māori history

– New Zealand Government {{DEFAULTSORT:Maori History

Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

n settlers in New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

(''Aotearoa

''Aotearoa'' () is the Māori name for New Zealand. The name was originally used by Māori in reference only to the North Island, with the whole country being referred to as ''Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu'' – where ''Te Ika-a-Māui'' means N ...

'' in Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

), in a series of ocean migrations in canoes starting from the late 13th or early 14th centuries. Over time, in isolation, the Polynesian settlers developed a distinct Māori culture

Māori culture () is the customs, cultural practices, and beliefs of the Māori people of New Zealand. It originated from, and is still part of, Polynesians, Eastern Polynesian culture. Māori culture forms a distinctive part of Culture of New ...

.

Early Māori history is often divided into two periods: the Archaic period () and the Classic period (). Archaeological sites such as Wairau Bar

The Wairau Bar, or Te Pokohiwi, is a gravel bar formed where the Wairau River meets the sea in Cloudy Bay, Marlborough, north-eastern South Island, New Zealand. It is an important archaeological site, settled by explorers from East Polynesia ...

show evidence of early life in Polynesian settlements in New Zealand. Many crops the settlers brought from Polynesia did not grow well in the colder New Zealand climates. However, many native birds and marine species were hunted or collected for food, with birds sometimes to extinction. An increasing population, competition for resources, and changes to the new local climate led to social and cultural changes during the Classic period. A more elaborate art form developed, and a new warrior culture emerged with fortified villages known as pā

The word pā (; often spelled pa in English) can refer to any Māori people, Māori village or defensive settlement, but often refers to hillforts – fortified settlements with palisades and defensive :wikt:terrace, terraces – and also to fo ...

. One group of Māori settled in the Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ; Moriori language, Moriori: , 'Misty Sun'; ) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island, administered as part of New Zealand, and consisting of about 10 islands within an approxima ...

around 1500; they created a separate, pacifist culture and became known as the Moriori

The Moriori are the first settlers of the Chatham Islands ( in Moriori language, Moriori; in Māori language, Māori). Moriori are Polynesians who came from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 AD, which was close to the time of the ...

.

The arrival of Europeans to New Zealand, starting in 1642 with Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch sea explorer, seafarer and exploration, explorer, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first European to reach New ...

, brought enormous changes to the Māori, who were introduced to Western food, technology, weapons and culture by European settlers, predominantly from Britain. In 1840, the British Crown and many Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

, allowing New Zealand to become part of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

and granting Māori the status of British subjects. Initial relations between Māori and Europeans (whom the Māori called "Pākehā

''Pākehā'' (or ''Pakeha''; ; ) is a Māori language, Māori-language word used in English, particularly in New Zealand. It generally means a non-Polynesians, Polynesian New Zealanders, New Zealander or more specifically a European New Zeala ...

") were largely amicable. However, rising tensions over disputed land sales led to conflict in the 1860s and large-scale land confiscations. Social upheaval and virgin soil epidemic

In epidemiology, a virgin soil epidemic is an epidemic in which populations that previously were in isolation from a pathogen are immunologically unprepared upon contact with the novel pathogen. Virgin soil epidemics have occurred with European ...

s also took a devastating toll on the Māori people, causing their population to decline and their standing in New Zealand to diminish.

But by the start of the 20th century, the Māori population had begun to recover, and efforts had been made to increase their social, political, cultural, and economic standing in wider New Zealand society. A protest movement

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration, or remonstrance) is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate ...

gained support in the 1960s, seeking redress for historical grievances. In the 2013 census, approximately 600,000 people in New Zealand identified as Māori, making up roughly 15 percent of the national population.

Origins from Polynesia

Austronesian

Austronesian may refer to:

*The Austronesian languages

*The historical Austronesian peoples

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Sout ...

ancestors moved south to the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

where they settled for some time. From there, some eventually sailed southeast, skirting the northern and eastern fringes of Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from New Guinea in the west to the Fiji Islands in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Vanu ...

along the coasts of Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea, officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is an island country in Oceania that comprises the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and offshore islands in Melanesia, a region of the southwestern Pacific Ocean n ...

and the Bismarck Islands

The Bismarck Archipelago (, ) is a group of islands off the northeastern coast of New Guinea in the western Pacific Ocean and is part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. Its area is about .

History

The first inhabitants of the archipelag ...

to the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands, also known simply as the Solomons,John Prados, ''Islands of Destiny'', Dutton Caliber, 2012, p,20 and passim is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 1000 smaller islands in Melanesia, part of Oceania, t ...

where they again settled, leaving shards of their Lapita

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their distinct material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE. The Lapita people are believed to have originated fro ...

pottery behind and picking up a small amount of Melanesian DNA. From there, some migrated down to the western Polynesian islands of Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

and Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

. Others island-hopped eastward, all the way from Otong Java in the Solomons to the Society Islands

The Society Islands ( , officially ; ) are an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean that includes the major islands of Tahiti, Mo'orea, Moorea, Raiatea, Bora Bora and Huahine. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country ...

of Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

and Raʻiātea (once called Havai'i, or Hawaiki

(also rendered as in the Cook Islands, Hawaiki in Māori, in Samoan, in Tahitian, in Hawaiian) is, in Polynesian folklore, the original home of the Polynesians, before dispersal across Polynesia. It also features as the underworld in man ...

). From there, a succession of migrant waves colonised the rest of eastern Polynesia, as far as Hawai'i in the north, the Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands ( ; or ' or ' ; Marquesan language, Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan language, North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan language, South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcano, volcanic islands in ...

and Rapa Nui

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

(Easter Island) in the east, and lastly, New Zealand in the far south.

Analysis by Kayser ''et al.'' (2008) discovered that only 21 per cent of the Māori-Polynesian autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosome ...

gene pool is of Melanesian origin, with the rest (79 per cent) being of East Asian origin. Another study by Friedlaender ''et al.'' (2008) also confirmed that Polynesians are closer genetically to Micronesians

The Micronesians or Micronesian peoples are various closely related ethnic groups native to Micronesia, a region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They are a part of the Austronesian ethnolinguistic group, which has an Urheimat in Taiwan.

Eth ...

, Taiwanese indigenous peoples

Taiwanese indigenous peoples, formerly called Taiwanese aborigines, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about 600,303 or 3% of the Geography of Taiwan, island's population. This total is incr ...

, and East Asians

East Asian people (also East Asians) are the people from East Asia, which consists of China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. The total population of all countries within this region is estimated to be 1.677 billion and 21% ...

, than to Melanesians

Melanesians are the predominant and Indigenous peoples of Oceania, indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia, in an area stretching from New Guinea to the Fiji Islands. Most speak one of the many languages of the Austronesian languages, Austronesian l ...

. The study concluded that Polynesians moved through Melanesia relatively rapidly, allowing only limited admixture between Austronesians and Melanesians. The Polynesian population experienced a founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, us ...

and genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as random genetic drift, allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the Allele frequency, frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene va ...

. Evidence of an ancestral phase in the southern Philippines comes from the discovery that Polynesians share about 40 percent of their DNA with Filipinos

Filipinos () are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. Filipinos come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino language, Filipino, Philippine English, English, or other Philippine language ...

from this area.

Settlement of New Zealand

In New Zealand, there are no human remains, artefacts or structures which are confidently dated to earlier than the Kaharoa Tephra, a layer of volcanic debris deposited by theMount Tarawera

Mount Tarawera is a volcano on the North Island of New Zealand within the older but volcanically productive Ōkataina Caldera. Located 24 kilometres southeast of Rotorua, it consists of a series of rhyolitic lava domes that were fissured ...

eruption around 1314 CE. The 1999 dating of some Polynesian rat

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), or , is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. Contrary to its vernacular name, the Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asi ...

(kiore) bones to as early as 10 CE was later found to be an error. New samples of rat bone (and also of rat-gnawed shells and woody seed cases) gave dates later than the Tarawera eruption except for three which dated to a decade or so before the eruption.

Pollen evidence of widespread forest fires a decade or two before the eruption has led some scientists to speculate that humans may have lit them, in which case the first settlement date could have been somewhere in the period between 1280 and 1320 CE. However, the most recent synthesis of archaeological and genetic evidence concludes that, whether or not some settlers arrived before the Tarawera eruption, the main settlement period was in the decades after it, somewhere between 1320 and 1350 CE, possibly involving a coordinated mass migration. This scenario is also consistent with a much debated third line of evidence – traditional genealogies () which point to 1350 AD as a probable arrival date for many of the founding canoes ( waka) from which many Māori trace their descent.

Māori oral history describes ancestors' arrival in several large ocean-going waka, from Hawaiki

(also rendered as in the Cook Islands, Hawaiki in Māori, in Samoan, in Tahitian, in Hawaiian) is, in Polynesian folklore, the original home of the Polynesians, before dispersal across Polynesia. It also features as the underworld in man ...

. Hawaiki is the spiritual homeland of many eastern Polynesian societies and was considered mythical. However, researchers think it is a real place – the traditionally important island of Raʻiātea in the Leeward Society Islands (in French Polynesia

French Polynesia ( ; ; ) is an overseas collectivity of France and its sole #Governance, overseas country. It comprises 121 geographically dispersed islands and atolls stretching over more than in the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. The t ...

), which, in the local dialect, was called Havai'i. Migration accounts vary among iwi

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori, roughly means or , and is often translated as "tribe". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, and is typically pluralised as such in English.

...

, whose members may identify with several waka in their genealogies.

With them the settlers brought several species that thrived: the kūmara

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant in the morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its sizeable, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable, which is a staple food in parts of the ...

, taro

Taro (; ''Colocasia esculenta'') is a root vegetable. It is the most widely cultivated species of several plants in the family Araceae that are used as vegetables for their corms, leaves, stems and Petiole (botany), petioles. Taro corms are a ...

, yams, gourd

Gourds include the fruits of some flowering plant species in the family Cucurbitaceae, particularly '' Cucurbita'' and '' Lagenaria''. The term refers to a number of species and subspecies, many with hard shells, and some without. Many gourds ha ...

, tī, aute (paper mulberry) – and Polynesian dogs and rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include '' Neotoma'' (pack rats), '' Bandicota'' (bandicoo ...

s. It is likely that other species from their homeland were also brought but did not survive the journey or thrive on arrival.

In the last few decades, mitochondrial-DNA (mtDNA) research has allowed an estimate to be made of the number of women in the founding population of between 50 and 100.

A 2022 study using radiocarbon technology from over 500 archaeological sites states that 'early Māori settlement happened in the North Island between AD 1250 and AD 1275', similar to a 2010 study indicating 1280 as an arrival time.

Archaic period (c. 1280 – c. 1500)

The earliest period of Māori settlement is known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period. The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct

The earliest period of Māori settlement is known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period. The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct moa

Moa are extinct giant flightless birds native to New Zealand.

Moa or MOA may also refer to:

Arts and media

* Metal Open Air, a Brazilian heavy metal festival

* MOA Museum of Art in Japan

* The Moas, New Zealand film awards

People

* Moa ...

species weighing between and each. Other species, also now extinct, included the New Zealand swan, the New Zealand goose and the giant Haast's eagle

Haast's eagle (''Hieraaetus moorei'') is an Extinction, extinct species of eagle that lived in the South Island of New Zealand, commonly accepted to be the of Māori mythology.

, which preyed upon the moa. Marine mammals – seals in particular – thronged the coasts, with evidence of coastal colonies much further north than those which remain . Huge numbers of moa bones – estimated to be from between 29,000 and 90,000 birds – have been located at the mouth of the Waitaki River

The Waitaki River is a large braided river in the South Island of New Zealand. It drains the Mackenzie Basin and runs south-east to enter the Pacific Ocean between Timaru and Oamaru on the east coast. It starts at the confluence of the Ōhau Ri ...

, between Timaru

Timaru (; ) is a port city in the southern Canterbury Region of New Zealand, located southwest of Christchurch and about northeast of Dunedin on the eastern Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast of the South Island. The Timaru urban area is home to peo ...

and Oamaru

Oamaru (; ) is the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, it is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is south of Timaru and north of Dunedin on the Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast; State Highway 1 (New Zealand), Sta ...

on the east coast of the South Island

The South Island ( , 'the waters of Pounamu, Greenstone') is the largest of the three major islands of New Zealand by surface area, the others being the smaller but more populous North Island and Stewart Island. It is bordered to the north by ...

. Further south, at the mouth of the ( Shag River), evidence suggests that at least 6,000 moa were slaughtered by humans over a relatively short period of time.

Archaeology has shown that the Otago

Otago (, ; ) is a regions of New Zealand, region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island and administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local go ...

region was the node of Māori cultural development during this time, and the majority of archaic settlements were on or within of the coast. It was common for people to establish small temporary camps far inland for seasonal hunting. Settlements ranged in size from 40 people (e.g., Palliser Bay in Wellington) to between 300 and 400 people, with forty buildings (such as at Shag River).

The best-known and most extensively studied Archaic site is at Wairau Bar

The Wairau Bar, or Te Pokohiwi, is a gravel bar formed where the Wairau River meets the sea in Cloudy Bay, Marlborough, north-eastern South Island, New Zealand. It is an important archaeological site, settled by explorers from East Polynesia ...

in the South Island. The site is similar to eastern Polynesian nucleated village

A nucleated village, or clustered settlement, is one of the main types of settlement pattern. It is one of the terms used by geographers and landscape historians to classify settlements. It is most accurate with regard to planned settlements: its ...

s and is the only New Zealand archaeological site containing the bones of people who were born elsewhere. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

of charcoal, human bone, moa bone, estuarine shells and moa eggshell has produced a wide range of date estimates, from the early 13th to the early 15th centuries, many of which might be contaminated by "inbuilt age" from older carbon which was eaten or absorbed by the sampled organisms. Due to tectonic forces, including several earthquakes and tsunamis since human arrival, some of the Wairau Bar site is now underwater. Work on the Wairau Bar skeletons in 2010 showed that life expectancy was very short, the oldest skeleton being 39 and most people dying in their 20s. Most of the adults showed signs of dietary or infection stress. Anaemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availab ...

and arthritis

Arthritis is a general medical term used to describe a disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, Joint effusion, swelling, and decreased range of motion of ...

were common. Infections such as tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

(TB) may have been present, as the symptoms were present in several skeletons. On average, the adults were taller than other South Pacific people, at for males and for females.

The Archaic period is remarkable for the lack of weapons and fortifications so typical of the later "Classic" Māori, and for its distinctive "reel necklaces"."Nga Kakano: 1100 – 1300"Te Papa From this period onward, some 32 species of birds became extinct, either through over-predation by humans and the ''kiore'' and (Polynesian Dog) they introduced; repeated burning of the vegetation that changed their habitat; or climate cooling, which appears to have occurred from about 1400–1450. For a short period – less than 200 years – the early Māori diet included an abundance of large birds and fur seals that had never been hunted before. These animals rapidly declined: many, such as the various moa species, the New Zealand swan and the kōhatu shag becoming extinct; while others, such as

kākāpō

The kākāpō (; : ; ''Strigops habroptilus''), sometimes known as the owl parrot or owl-faced parrot, is a species of large, nocturnal, ground-dwelling parrot of the superfamily Strigopoidea. It is endemic to New Zealand.

Kākāpō can be u ...

and seals were reduced in range and number.

Work by Helen Leach

Helen May Leach (née Keedwell; born 3 July 1945) is a New Zealand academic specialising in food anthropology. She is currently a professor emerita at the University of Otago.

Early life and family

Born Helen May Keedwell in Wellington on 3 J ...

shows that Māori were using about 36 different food plants, although many required detoxification and long periods (12–24 hours) of cooking. D. Sutton's research on early Māori fertility found that first pregnancy occurred at about 20 years and the mean number of births was low, compared with other neolithic societies. The low number of births may have been due to the very low average life expectancy of 31–32 years. Analysis of skeletons at Wairau Bar showed signs of a hard life, with many having had broken bones that had healed. This suggests that the people ate a balanced diet and enjoyed a supportive community that had the resources to support severely injured family members.

Classic period (1500–1768)

The cooling of the climate, confirmed by a detailed tree-ring study near

The cooling of the climate, confirmed by a detailed tree-ring study near Hokitika

Hokitika is a town in the West Coast region of New Zealand's South Island, south of Greymouth, and close to the mouth of the Hokitika River. It is the seat and largest town in the Westland District. The town's estimated population is as of ...

, shows a significant, sudden and long-lasting cooler period from 1500 . This coincided with a series of massive earthquakes in the South Island Alpine fault, a major earthquake in 1460 in the Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

area, tsunamis

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, la ...

that destroyed many coastal settlements, and the extinction of the moa and other food species. These were likely factors that led to sweeping changes in the Māori culture, which developed into the "Classic" period that was in place at the time of European contact.

This period is characterised by finely made (greenstone) weapons and ornaments, elaborately carved canoes – a tradition that was later extended to and continued in elaborately carved meeting houses called Neich Roger, 2001. ''Carved Histories: Rotorua Ngati Tarawhai Woodcarving''. Auckland: Auckland University Press, pp 48–49. – and a fierce warrior culture. They developed hillfort

A hillfort is a type of fortification, fortified refuge or defended settlement located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typical of the late Bronze Age Europe, European Bronze Age and Iron Age Europe, Iron Age. So ...

s known as , practised cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

, and built some of the largest war canoes () ever made.

Around the year 1500, a group of Māori migrated east to ''Rēkohu'', now known as the Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ; Moriori language, Moriori: , 'Misty Sun'; ) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island, administered as part of New Zealand, and consisting of about 10 islands within an approxima ...

. There they adapted to the local climate and the availability of resources and developed into a people known as the Moriori

The Moriori are the first settlers of the Chatham Islands ( in Moriori language, Moriori; in Māori language, Māori). Moriori are Polynesians who came from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 AD, which was close to the time of the ...

, related to but distinct from the Māori of mainland New Zealand. A notable feature of Moriori culture was an emphasis on pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

. When a party of invading North Taranaki

Taranaki is a regions of New Zealand, region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano Mount Taranaki, Taranaki Maunga, formerly known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the ...

Māori arrived in 1835, few of the estimated Moriori population of 2,000 survived; they were killed outright and many were enslaved.

Early European contact (1769–1840)

The New Zealand historian, Michael King, describes the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world". Besides a brief offshore skirmish with Abel Tasman in 1642, the first encounter with the outside world took place with Captain Cook's party on his first voyage in 1769, followed by later contact in 1773 and 1777 during the second and third voyages. Cook spent time mapping the islands in 1769 and meeting Māori, particularly in the Marlborough Sounds in 1777. Cook and his crew recorded their impressions of Māori at the time. This early contact proved problematic and sometimes fatal, with some Europeans being cannibalised.

The New Zealand historian, Michael King, describes the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world". Besides a brief offshore skirmish with Abel Tasman in 1642, the first encounter with the outside world took place with Captain Cook's party on his first voyage in 1769, followed by later contact in 1773 and 1777 during the second and third voyages. Cook spent time mapping the islands in 1769 and meeting Māori, particularly in the Marlborough Sounds in 1777. Cook and his crew recorded their impressions of Māori at the time. This early contact proved problematic and sometimes fatal, with some Europeans being cannibalised.

From the 1780s, Māori encountered European and American

From the 1780s, Māori encountered European and American sealers Sealer may refer either to a person or ship engaged in seal hunting, or to a sealant; associated terms include:

Seal hunting

* Sealer Hill, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica

* Sealers' Oven, bread oven of mud and stone built by sealers around 1800 ...

and whalers. Some Māori crewed on the foreign ships, with many crewing on whaling and sealing ships that operated in New Zealand waters. Some of the South Island crews were almost totally Māori. Between 1800 and 1820, there were 65 sealing voyages and 106 whaling voyages to New Zealand, mainly from Britain and Australia. A trickle of escaped convicts from Australia and deserters from visiting ships, as well as early Christian missionaries

A Christian mission is an organized effort to carry on evangelism, in the name of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries. Sometimes individuals are sent and ...

, also exposed the indigenous population to outside influences. During the Boyd Massacre in 1809, Māori took hostage and killed 66 members of the crew and passengers of the sailing ship ''Boyd'' in apparent revenge for the captain whipping the son of a Māori chief. Given accounts of cannibalism in this attack, shipping companies and missionaries kept their distance, significantly reducing their contact with the Māori for several years.

The runaways were of various standing within Māori society, ranging from slaves to high-ranking advisors. Some runaways remained little more than prisoners, while others abandoned European culture and identified as Māori. These Europeans "gone native" became known as Pākehā Māori. Many Māori valued them as a means to acquire European knowledge and technology, particularly firearms. When Whiria (Pōmare II

Pōmare II (c. 1782 – 7 December 1821) (fully Tu Tunuieaiteatua Pōmare II or in modern orthography Tū Tū-nui-ʻēʻa-i-te-atua Pōmare II; historically misspelled as Tu Tunuiea'aite-a-tua), was the second king of Tahiti between 1782 and 182 ...

) led a war-party against Tītore

Tītore ( 1775–1837), sometimes known as Tītore Tākiri, was a rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe). He was a war leader of the Ngāpuhi who led the war expedition against the Māori people, Māori tribes at East Cape in 1820 and 18 ...

in 1838, he had 131 Europeans among his warriors. Frederick Edward Maning, an early settler, wrote two lively accounts of life in these times, which have become classics of New Zealand literature

New Zealand literature is literature, both oral and written, produced by the people of New Zealand. It often deals with New Zealand themes, people or places, is written predominantly in New Zealand English, and features Māori culture and the ...

: ''Old New Zealand'' and ''History of the War in the North of New Zealand against the Chief Heke''. European settlement of New Zealand increased steadily. By 1839, estimates placed the number of Europeans living among the Māori as high as 2,000, two-thirds of whom lived in the North Island, especially in the Northland Peninsula

The Northland Peninsula, called the North Auckland Peninsula in earlier times, is in the far north of the North Island of New Zealand. It is joined to the rest of the island by the Auckland isthmus, a narrow piece of land between the Waitemat� ...

.

Between 1805 and 1840, the acquisition of musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually dis ...

s by tribes in close contact with European visitors drove a desperate need to acquire muskets to avoid extermination by, and allow aggression against, their neighbours; the recent introduction of the potato

The potato () is a starchy tuberous vegetable native to the Americas that is consumed as a staple food in many parts of the world. Potatoes are underground stem tubers of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'', a perennial in the nightshade famil ...

allowed more distant campaigns and more time for campaigning among Māori tribes. This led to a period of particularly bloody intertribal warfare known as the Musket Wars

The Musket Wars were a series of as many as 3,000 battles and raids fought throughout New Zealand (including the Chatham Islands) among Māori people, Māori between 1806 and 1845, after Māori first obtained muskets and then engaged in an inte ...

, in which many groups were decimated and others driven from their traditional territory. The absolute requirement for trade goods – mostly New Zealand flax

New Zealand flax describes the common New Zealand perennial plants ''Phormium tenax'' and '' Phormium colensoi'', known by the Māori names ''harakeke'' and ''wharariki'' respectively. Although given the common name 'flax' they are quite disti ...

, though ' (tattooed heads) were also saleable – led many Māori to move to unhealthy swamplands where flax could be grown. It has been estimated that during this period the Māori population dropped from about 100,000 (in 1800) to between 50,000 and 80,000 by the wars' end in 1843. The picture is confused by uncertainty over how or if Pākehā Māori were counted, and by the near-extermination of many of the less powerful and (subtribes) during the wars. The pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

Moriori

The Moriori are the first settlers of the Chatham Islands ( in Moriori language, Moriori; in Māori language, Māori). Moriori are Polynesians who came from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 AD, which was close to the time of the ...

in the Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ; Moriori language, Moriori: , 'Misty Sun'; ) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island, administered as part of New Zealand, and consisting of about 10 islands within an approxima ...

similarly suffered massacre and subjugation at the hands of some Ngāti Mutunga

Ngāti Mutunga is a Māori iwi (tribe) of New Zealand, whose original tribal lands were in north Taranaki. They migrated, first to Wellington (with Ngāti Toa and other Taranaki hapū), and then to the Chatham Islands (along with Ngāti Tama) ...

and Ngāti Tama

Ngāti Tama is a Māori people, Māori iwi, tribe of New Zealand. Their origins, according to oral tradition, date back to Tama Ariki, the chief navigator on the Tokomaru (canoe), Tokomaru waka (canoe), waka. Their historic region is in north Tar ...

who had fled from the Taranaki

Taranaki is a regions of New Zealand, region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano Mount Taranaki, Taranaki Maunga, formerly known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the ...

region.

At the same time, the Māori suffered high mortality rates from Eurasian infectious diseases, such as influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

and measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

, which killed an unknown number of Māori: estimates vary between 10 and 50 per cent. The spread of epidemics

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of Host (biology), hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example ...

resulted largely from the Māori lacking acquired immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity ...

to the new diseases. The 1850s were a decade of relative stability and economic growth for Māori. A huge influx of European settlers in the 1870s increased contact between the indigenous people and the newcomers.

Te Rangi Hīroa

Sir Peter Henry Buck ( October 18771 December 1951), also known as Te Rangi Hīroa or Te Rangihīroa, was a New Zealand anthropologist and an expert on Māori culture, Māori and Polynesian cultures who served many roles through his life: as a ...

documents an epidemic caused by a respiratory disease that Māori called . It "decimated" populations in the early 19th century and "spread with extraordinary virulence throughout the North Island and even to the South... Measles, typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

, scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'', a Group A streptococcus (GAS). It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age. The signs and symptoms include a sore ...

, whooping cough

Whooping cough ( or ), also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable Pathogenic bacteria, bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common c ...

and almost everything, except plague and sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is caused by the species '' Trypanosoma b ...

, have taken their toll of Maori dead".

Contact with Europeans led to a sharing of concepts. The Māori language was first written down by

Contact with Europeans led to a sharing of concepts. The Māori language was first written down by Thomas Kendall

Thomas Kendall (13 December 1778 – 6 August 1832) was a schoolmaster, an early missionary to Māori people in New Zealand, and a recorder of the Māori language. An evangelical Anglican, he and his family were in the first group of mission ...

in 1815, in '' A korao no New Zealand''. This was followed five years later by ''A Grammar and Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language'', compiled by Professor Samuel Lee and aided by Kendall, and the chiefs Hongi Hika

Hongi Hika ( – 6 March 1828) was a New Zealand Māori rangatira (chief) and war leader of the iwi of Ngāpuhi. He was a pivotal figure in the early years of regular European contact and settlement in New Zealand. As one of the first Māor ...

and Waikato

The Waikato () is a region of the upper North Island of New Zealand. It covers the Waikato District, Waipā District, Matamata-Piako District, South Waikato District and Hamilton City, as well as Hauraki, Coromandel Peninsula, the nort ...

, on a visit to England in 1820. Māori quickly adopted writing as a means of sharing ideas, and many of their oral stories and poems were converted to the written form. Between February 1835 and January 1840, William Colenso

William Colenso (17 November 1811 – 10 February 1899) FRS was a Cornish Christian missionary to New Zealand, and also a printer, botanist, explorer and politician. He attended the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and later wrote an acco ...

printed 74,000 Māori-language booklets from his press at Paihia

Paihia is a town in the Bay of Islands in the Northland Region of the North Island of New Zealand. It is 60 kilometres north of Whangārei, located close to the historic towns of Russell, New Zealand, Russell and Kerikeri. Missionary Henry Wi ...

. In 1843, the government distributed free gazettes to Māori called ''Ko Te Karere O Nui Tireni''. These contained information about law and crimes, with explanations and remarks about European customs, and were "designed to pass on official information to Māori and to encourage the idea that Pākehā and Māori were contracted together under the Treaty of Waitangi".

Treaty of Waitangi with the British Crown (1840)

Before 1840, New Zealand was not formally part of the empire and was therefore beyond the reaches of British law. In 1839, with ongoing stories of increasing lawlessness and uncontrolled land speculation by British subjects reaching London, the government finally decided to intervene. On 6 May 1839, it expanded the New South Wales colony to include New Zealand and it dispatched the Royal Navy captain,William Hobson

Captain William Hobson (26 September 1792 – 10 September 1842) was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Royal Navy, who served as the first Governor of New Zealand. He was a co-author of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Hobson was dispatched f ...

, with instructions to establish sovereignty over all or part of New Zealand after negotiation with Māori, and to set up a colony. On 6 February 1840, Hobson signed the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

with many North Island chiefs at Waitangi. Most other chiefs from around New Zealand signed the treaty during 1840: some chiefs refused to sign. In May 1840, Hobson established British sovereignty, in two declarations. First, over the North Island based on cession

The act of cession is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty. Ballentine's Law Dictionary defines cession as "a surrender; a giving up; a relinquishment of jurisdicti ...

and second, over the South Island, based on its being terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

Since the nineteenth century it has occasionally been used in international law as a principle to justify claims that territory may be acquired ...

. Hobson then became the colony's first governor.

The Treaty gave Māori the rights of British subjects

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

and guaranteed Māori property rights and tribal autonomy, in return for accepting British sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

. Considerable dispute continues over aspects of the Treaty of Waitangi. The original treaty was written mainly by James Busby

James Busby (7 February 1802 – 15 July 1871) was the British Resident in New Zealand from 1833 to 1840. He was involved in drafting the 1835 Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. As British Residen ...

and translated into Māori by Henry Williams Henry Williams may refer to:

Politicians

* Henry Williams (activist) (born 2000), chief of staff of the Mike Gravel 2020 presidential campaign

* Henry Williams (MP for Northamptonshire) (died 1558), member of parliament (MP) for Northamptonshire ...

, who was moderately proficient in Māori, and his son William, who was more skilled. At Waitangi, the chiefs signed the Māori translation.

Land disputes and conflict

Despite conflicting interpretations of the provisions of the Treaty of Waitangi, relations between Māori and Europeans during the early colonial period were largely peaceful. Many Māori groups set up substantial businesses, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas markets. Some of the early European settlers learned the Māori language and recordedMāori mythology

Māori mythology and Māori traditions are two major categories into which the remote oral history of New Zealand's Māori people, Māori may be divided. Māori myths concern tales of supernatural events relating to the origins of what was the ...

, including George Grey

Sir George Grey, KCB (14 April 1812 – 19 September 1898) was a British soldier, explorer, colonial administrator and writer. He served in a succession of governing positions: Governor of South Australia, twice Governor of New Zealand, Gov ...

, Governor of New Zealand from 1845 to 1855 and 1861–1868.

However, rising tensions over disputed land purchases and attempts by Māori in the Waikato to establish what some saw as a rival to the British system of royalty – viz. the Māori King Movement

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

() – led to the New Zealand wars

The New Zealand Wars () took place from 1845 to 1872 between the Colony of New Zealand, New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori people, Māori on one side, and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. Though the wars were initi ...

in the 1860s. These conflicts started when rebel Māori attacked isolated settlers in Taranaki but were fought mainly between Crown troops – from both Britain and new regiments raised in Australia, aided by settlers and some allied Māori (known as ''kūpapa'') – and numerous Māori groups opposed to the disputed land sales, including some Waikato Māori.

While these conflicts resulted in few Māori (compared to the earlier Musket wars) or European deaths, the colonial government confiscated tracts of tribal land as punishment for what were called rebellions. In some cases the government confiscated land from tribes that had taken no part in the war, although this was almost immediately returned. Some of the confiscated land was returned to both kupapa and "rebel" Māori. Several minor conflicts also arose after the wars, including the incident at Parihaka

Parihaka is a community in the Taranaki region of New Zealand, located between Mount Taranaki and the Tasman Sea. In the 1870s and 1880s the settlement, then reputed to be the largest Māori people, Māori village in New Zealand, became the centre ...

in 1881 and the Dog Tax War from 1897 to 1898.

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 established the Native Land Court, which was intended to transfer Māori land from communal ownership into individual household title as a means to assimilate and to facilitate greater sales to European immigrants. Māori land under individual title became available to be sold to the colonial government or to settlers in private sales. Between 1840 and 1890, Māori sold 95 per cent of their land (63,000,000 of in 1890). In total 4 per cent of this was confiscated land, although about a quarter of this was returned. 300,000 acres was returned to Kupapa Māori mainly in the lower Waikato River Basin area. Individual Māori titleholders received considerable capital from these land sales, with some lower Waikato Chiefs being given 1000 pounds each. Disputes later arose over whether or not promised compensation in some sales was fully delivered. Some claim that later, the selling off of Māori land and the lack of appropriate skills hampered Māori participation in developing the New Zealand economy, eventually diminishing the capacity of many Māori to sustain themselves.

The Māori MP Henare Kaihau, from Waiuku

Waiuku is a rural town in the Auckland Region of New Zealand. It is located at the southern end of the Waiuku River, which is an estuary, estuarial arm of the Manukau Harbour, and lies on the isthmus of the Āwhitu Peninsula, which extends to th ...

, who was executive head of the King Movement, worked alongside King Mahuta to sell land to the government. At that time the king sold 185,000 acres per year. In 1910 the Māori Land Conference at Waihi discussed selling a further 600,000 acres. King Mahuta had been successful in getting restitution for some blocks of land previously confiscated, and these were returned to the King in his name. Henare Kaihau invested all the money, 50,000 pounds, in an Auckland land company which collapsed; all 50,000 pounds of the Kīngitanga money was lost.

In 1884 King Tāwhiao

''Kīngitanga, Kīngi'' Tāwhiao (Tūkaroto Matutaera Pōtatau Te Wherowhero Tāwhiao, ; c. 1822 – 26 August 1894), known initially as Matutaera, reigned as the Māori King Movement, Māori King from 1860 until his death. After his flight to ...

withdrew money from the Kīngitanga bank, Te Peeke o Aotearoa, to travel to London to see Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

and try to persuade her to honour the Treaty between their peoples. He did not get past the Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

, who said it was a New Zealand problem. Returning to New Zealand, the Premier Robert Stout

Sir Robert Stout (28 September 1844 – 19 July 1930) was a New Zealand politician who was the 13th premier of New Zealand on two occasions in the late 19th century, and later Chief Justice of New Zealand. He was the only person to hold both ...

insisted that all events happening before 1863 were the responsibility of the Imperial Government.

By 1891 Māori comprised just 10 per cent of the population but still owned 17 per cent of the land, although much of it was of poor quality.

Decline and revival

By the late 19th century a widespread belief existed amongst both Pākehā and Māori that the Māori population would cease to exist as a separate race or culture, and become assimilated into the European population. In 1840, New Zealand had a Māori population of about 50,000 to 70,000 and only about 2,000 Europeans. By 1860 the Europeans had increased to 50,000. The Māori population had declined to 37,520 in the 1871 census, althoughTe Rangi Hīroa

Sir Peter Henry Buck ( October 18771 December 1951), also known as Te Rangi Hīroa or Te Rangihīroa, was a New Zealand anthropologist and an expert on Māori culture, Māori and Polynesian cultures who served many roles through his life: as a ...

(Sir Peter Buck) believed this figure was too low. The figure was 42,113 in the 1896 census, by which time Europeans numbered more than 700,000. Professor Ian Pool noticed that as late as 1890, 40 per cent of all female Māori children who were born died before the age of one, a much higher rate than for males.

The decline of the Māori population did not continue; it stabilised and began to recover. By 1936 the Māori figure was 82,326, although the sudden rise in the 1930s was probably due to the introduction of the family benefit, payable only when a birth was registered, according to Professor Pool. Despite a substantial level of intermarriage between the Māori and European populations, many ethnic Māori retained their cultural identity. A number of discourses developed as to the meaning of "Māori" and to who counted as Māori or not.

The parliament instituted four Māori seats in 1867, giving all Māori men universal suffrage, 12 years ahead of their European New Zealand counterparts. Until the 1879 general elections, men had to satisfy property requirements of landowning or rental payments to qualify as voters: owners of land worth at least £50, or payers of a certain amount in yearly rental (£10 for farmland or a city house, or £5 for a rural house). New Zealand was thus the first neo-European nation in the world to give the vote to its indigenous people. While the Māori seats encouraged Māori participation in politics, the relative size of the Māori population of the time ''vis à vis'' Pākehā

''Pākehā'' (or ''Pakeha''; ; ) is a Māori language, Māori-language word used in English, particularly in New Zealand. It generally means a non-Polynesians, Polynesian New Zealanders, New Zealander or more specifically a European New Zeala ...

would have warranted approximately 15 seats.

From the late 19th century, successful Māori politicians such as James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata,

From the late 19th century, successful Māori politicians such as James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hīroa

Sir Peter Henry Buck ( October 18771 December 1951), also known as Te Rangi Hīroa or Te Rangihīroa, was a New Zealand anthropologist and an expert on Māori culture, Māori and Polynesian cultures who served many roles through his life: as a ...

and Māui Pōmare

Sir Māui Wiremu Piti Naera Pōmare (1875 or 1876 – 27 June 1930) was a New Zealand medical doctor and politician, being counted among the more prominent Māori political figures. He is particularly known for his efforts to improve Māori he ...

, were influential in politics. At one point Carroll became Acting Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

. The group, known as the Young Māori Party, cut across voting-blocs in Parliament and aimed to revitalise the Māori people after the devastation of the previous century. They believed the future path called for a degree of assimilation, with Māori adopting European practices such as Western medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for patients, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

and education, especially learning English.

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, a Māori pioneer force was taken to Egypt but quickly was turned into a successful combat infantry battalion; in the last years of the war it was known as the "Māori Pioneer Battalion". It mainly comprised Te Arawa

Te Arawa is a confederation of Māori people, Māori iwi and hapū (tribes and sub-tribes) of New Zealand who trace their ancestry to the ''Arawa (canoe), Arawa'' migration canoe (''waka''). The tribes are based in the Rotorua and Bay of Plent ...

, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki

Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki is one of the three principal Māori people, Māori iwi of the Gisborne District, Tūranga district; the others being Rongowhakaata and Ngāi Tāmanuhiri, Ngai Tamanuhiri. It is numerically the largest of the three, with 6, ...

, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou

Ngāti Porou is a Māori iwi traditionally located in the East Cape and Gisborne regions of the North Island of New Zealand. It has the second-largest affiliation of any iwi, behind Ngāpuhi, with an estimated 102,480 people according to the ...

and Ngāti Kahungunu

Ngāti Kahungunu is a Māori iwi (tribe) located along the eastern coast of the North Island of New Zealand. The iwi is traditionally centred in the Hawke's Bay and Wairārapa regions. The Kahungunu iwi also comprises 86 hapū (sub-tribes ...

and later many Cook Islanders

Cook Islanders are residents of the Cook Islands, which is composed of 15 islands and atolls in Polynesia in the Pacific Ocean. Cook Islands Māori are the indigenous Polynesian people of the Cook Islands, although the Cook Islands is curre ...

; the Waikato and Taranaki tribes refused to enlist or be conscripted

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

.

Māori were badly hit by the 1918 influenza epidemic when the Māori battalion returned from the Western Front. The death rate from influenza for Māori was 4.5 times higher than for Pākehā. Many Māori, especially in the Waikato, were very reluctant to visit a doctor and went to a hospital only when the patient was nearly dead. To cope with isolation, Waikato Māori, under Te Puea's leadership, increasingly returned to the old Pai Mārire

The Pai Mārire movement (commonly known as Hauhau) was a syncretic Māori religion founded in Taranaki by the prophet Te Ua Haumēne. It flourished in the North Island from about 1863 to 1874. Pai Mārire incorporated biblical and Māori sp ...

(Hau hau) cult of the 1860s.

Until 1893, 53 years after the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori did not pay tax on land holdings. In 1893 a very light tax was payable only on leasehold land, and it was not till 1917 that Māori were required to pay a heavier tax equal to half that paid by other New Zealanders.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the government decided to exempt Māori from the conscription that applied to other citizens. The Māori volunteered in large numbers, forming the 28th or Māori Battalion. Altogether 16,000 Māori took part in the war. Māori, including Cook Islanders, made up 12 per cent of the total New Zealand force. 3,600 served in the Māori Battalion, the remainder serving in artillery, pioneers, home guard, infantry, airforce, and navy.

Recent history (1960s–present)

Since the 1960s, Māoridom has undergone a cultural revival concurrent with activism for social justice and a

Since the 1960s, Māoridom has undergone a cultural revival concurrent with activism for social justice and a protest movement

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration, or remonstrance) is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate ...

. Government recognition of the growing political power of Māori and political activism have led to limited redress for confiscation of land and for the violation of other property rights. In 1975 the Crown set up the Waitangi Tribunal

The Waitangi Tribunal (Māori: ''Te Rōpū Whakamana i te Tiriti o Waitangi'') is a New Zealand permanent commission of inquiry established under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975. It is charged with investigating and making recommendations on c ...

, a body with the powers of a Commission of Enquiry, to investigate and make recommendations on such issues, but it cannot make binding rulings; the Government need not accept the findings of the Waitangi Tribunal, and has rejected some of them. Since 1976, people of Māori descent may choose to enrol on either the general or Māori roll for general elections, and may vote in either Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

or general electorates, but not both.

During the 1990s and 2000s, the government negotiated with Māori to provide redress for breaches by the Crown of the guarantees set out in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. By 2006 the government had provided over NZ$900 million in settlements, much of it in the form of land deals. The largest settlement, signed on 25 June 2008 with seven Māori iwi, transferred nine large tracts of forested land to Māori control. As a result of the redress paid to many iwi, Māori now have significant interests in the fishing and forestry industries. There is a growing Māori leadership who are using the treaty settlements as an investment platform for economic development.

Despite a growing acceptance of Māori culture in wider New Zealand society, the settlements have generated controversy. Some people have complained that the settlements occur at a level of between 1 and 2.5 cents on the dollar of the value of the confiscated lands; conversely, some denounce the settlements and socioeconomic initiatives as amounting to race-based preferential treatment. Both of these sentiments were expressed during the New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy

The New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy is a debate in the politics of New Zealand. It concerns the ownership of the country's foreshore and seabed, with many Māori groups claiming that Māori have a rightful claim to title ( indige ...

in 2004.

See also

*Pre-Māori settlement of New Zealand theories

Since the early 1900s it has been accepted by archaeologists and anthropologists that Polynesians (who became the Māori people, Māori) were the first ethnic group to settle in New Zealand (first proposed by Captain James Cook). Before that ti ...

* Māori mythology

Māori mythology and Māori traditions are two major categories into which the remote oral history of New Zealand's Māori people, Māori may be divided. Māori myths concern tales of supernatural events relating to the origins of what was the ...

* History of New Zealand

The human history of New Zealand can be dated back to between 1320 and 1350 CE, when the main settlement period started, after it was discovered and settled by Polynesians, who developed a distinct Māori culture. Like other Pacific cultures, M ...

* History of Oceania

The history of Oceania includes the history of Australia, Easter Island, Fiji, Hawaii, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Western New Guinea and other Pacific island nations.

Prehistory

The prehistory of Oceania is divided into the prehist ...

References

External links

*Māori history

– New Zealand Government {{DEFAULTSORT:Maori History