Munich Conference on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Munich Agreement was reached in

The

The

Hitler's adjutant, Fritz Wiedemann, recalled after the war that he was "very shocked" by Hitler's new plans to attack Britain and France three to four years after "deal ngwith the situation" in Czechoslovakia. General

Hitler's adjutant, Fritz Wiedemann, recalled after the war that he was "very shocked" by Hitler's new plans to attack Britain and France three to four years after "deal ngwith the situation" in Czechoslovakia. General

Hitler felt cheated of the limited war against the Czechs which he had been aiming for all summer. In early October, Chamberlain's press secretary asked for a public declaration of German friendship with Britain to strengthen Chamberlain's domestic position; Hitler instead delivered speeches denouncing Chamberlain's "governessy interference." In August 1939, shortly before the invasion of Poland, Hitler told his generals: "Our enemies are men below average, not men of action, not masters. They are little worms. I saw them at Munich."

Before the Munich Agreement, Hitler's determination to invade Czechoslovakia on 1 October 1938 had provoked a major crisis in the German command structure. The Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck, protested in a lengthy series of memos that it would start a

Hitler felt cheated of the limited war against the Czechs which he had been aiming for all summer. In early October, Chamberlain's press secretary asked for a public declaration of German friendship with Britain to strengthen Chamberlain's domestic position; Hitler instead delivered speeches denouncing Chamberlain's "governessy interference." In August 1939, shortly before the invasion of Poland, Hitler told his generals: "Our enemies are men below average, not men of action, not masters. They are little worms. I saw them at Munich."

Before the Munich Agreement, Hitler's determination to invade Czechoslovakia on 1 October 1938 had provoked a major crisis in the German command structure. The Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck, protested in a lengthy series of memos that it would start a

Poland was building up a secret Polish organization in the area of

Poland was building up a secret Polish organization in the area of

On 5 October, Beneš resigned as

On 5 October, Beneš resigned as

''

In early November 1938, under the First Vienna Award, after the failed negotiations between Czechoslovakia and

In early November 1938, under the First Vienna Award, after the failed negotiations between Czechoslovakia and

Germany stated that the incorporation of Austria into the Reich resulted in borders with Czechoslovakia that were a great danger to German security, and that this allowed Germany to be encircled by the Western Powers.

Neville Chamberlain announced the deal at Heston Aerodrome as follows:

Later that day he stood outside 10 Downing Street and again read from the document and concluded:

Germany stated that the incorporation of Austria into the Reich resulted in borders with Czechoslovakia that were a great danger to German security, and that this allowed Germany to be encircled by the Western Powers.

Neville Chamberlain announced the deal at Heston Aerodrome as follows:

Later that day he stood outside 10 Downing Street and again read from the document and concluded:

excerpt

* Jordan, Nicole. "Léon Blum and Czechoslovakia, 1936–1938." ''French History'' 5#1 (1991): 48–73. * Lukes, Igor and Erik Goldstein, eds. ''The Munich crisis, 1938: prelude to World War II'' (1999); Essays by scholars

online

* * Record, Jeffrey. "The use and abuse of history: Munich, Vietnam and Iraq." ''Survival'' (2019) pp. 163–180. * Riggs, Bruce Timothy

"Geoffrey Dawson, editor of "The Times" (London), and his contribution to the appeasement movement" (PhD dissertation, U of North Texas, 1993 online)

bibliography pp 229–233. * Ripsman, Norrin M. and Jack S. Levy. 2008.

Wishful Thinking or Buying Time? The Logic of British Appeasement in the 1930s

" ''International Security'' 33(2): 148–181. * Smetana, Vít. "Ten propositions about Munich 1938. On the fateful event of Czech and European historywithout legends and national stereotypes." ''Czech Journal of Contemporary History'' 7.7 (2019): 5–14

online

* Thomas, Martin. "France and the Czechoslovak crisis." ''Diplomacy and Statecraft'' 10.23 (1999): 122–159. * Watt, Donald Cameron. ''How war came: the immediate origins of the Second World War, 1938–1939'' (1989) online free to borrow * Werstein, Irving. ''Betrayal: the Munich pact of 1938'' (1969

online free to borrow

* Wheeler-Bennett, John. ''Munich: Prologue to tragedy'' (1948).

The Munich Agreement

– Text of the Munich Agreement on-line

The Munich Agreement in contemporary radio news broadcasts

– Actual radio news broadcasts documenting evolution of the crisis

The Munich Agreement

Original reports from The Times

British Pathe newsreel (includes Chamberlain's speech at Heston aerodrome)

(

Peace: And the Crisis Begins

from a broadcast by Dorothy Thompson, 1 October 1938

Post-blogging the Sudeten Crisis

– A day by day summary of the crisis

Text of the 1942 exchange of notes nullifying the Munich agreement

Photocopy of The Munich Agreement from Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts in Berlin (text in German) and from The National Archives in London (map).

Map of Europe during Munich Agreement

at omniatlas

* List of Czechoslovak villages ceded to Germany, Hungary and Poland, a book in Slovak

''Územie a obyvatelstvo Slovenskej republiky a prehľad obcí a okresov odstúpenych Nemecku, Maďarsku a Poľsku''

Bratislava: Štátny štatistický úrad, 1939. 92 p. – available online at ULB's Digital Library {{Authority control 1938 conferences 1938 in France 1938 in Germany 1938 in Italy 1938 in the United Kingdom September 1938 in the United Kingdom Partition (politics) Treaties concluded in 1938 Treaties of Nazi Germany Treaties of the French Third Republic Treaties of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) Treaties of the United Kingdom Territorial evolution of Hungary 1930s in Munich September 1938 in Europe

Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the French Republic

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. The agreement provided for the German annexation of part of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

called the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

, where 3 million people, mainly ethnic Germans, lived. The pact is known in some areas as the Munich Betrayal (; ), because of a previous 1924 alliance agreement and a 1925 military pact between France and the Czechoslovak Republic.

Germany had started a low-intensity undeclared war on Czechoslovakia on 17 September 1938. In reaction, Britain and France on 20 September formally requested Czechoslovakia cede the Sudetenland territory to Germany. This was followed by Polish and Hungarian territorial demands brought on 21 and 22 September, respectively. Meanwhile, German forces conquered parts of the Cheb District

Cheb District () is a Okres, district in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic. Its capital is the town of Cheb. It is the westernmost district of the Czech Republic.

Administrative division

Cheb District is divided into three Districts of ...

and Jeseník District

Jeseník District () is a Okres, district in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. Its capital is the town of Jeseník. With approximately 36,000 inhabitants, it is the least populated district of the Czech Republic.

Administrative division

Je ...

, where battles included use of German artillery, Czechoslovak tanks, and armored vehicles. Lightly armed German infantry briefly overran other border counties before being repelled. Poland grouped its army units near its common border with Czechoslovakia and conducted an unsuccessful probing offensive on 23 September. Hungary moved its troops towards the border with Czechoslovakia, without attacking. The Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

announced its willingness to come to Czechoslovakia's assistance, provided the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

would be able to cross Polish and Romanian territory; both countries refused.

An emergency meeting of the main European powers–not including Czechoslovakia, although their representatives were present in the town, or the Soviet Union, an ally to France and Czechoslovakia–took place in Munich, on 29–30 September. An agreement was quickly reached on Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's terms, and signed by the leaders of Germany, France, Britain, and Italy. The Czechoslovak mountainous borderland marked a natural border between the Czech state and the Germanic states since the early Middle Ages; it also presented a major natural obstacle to a possible German attack. Strengthened by border fortifications, the Sudetenland was of absolute strategic importance to Czechoslovakia. On 30 September, Czechoslovakia submitted to the combination of military pressure by Germany, Poland, and Hungary, and diplomatic pressure by Britain and France, and agreed to surrender territory to Germany following the Munich terms.

The Munich Agreement was soon followed by the First Vienna Award

The First Vienna Award was a treaty signed on 2 November 1938 pursuant to the Vienna Arbitration, which took place at Vienna's Belvedere Palace. The arbitration and award were direct consequences of the previous month's Munich Agreement, whic ...

on 2 November 1938, separating largely Hungarian inhabited territories in southern Slovakia and southern Subcarpathian Rus'

Transcarpathia (, ) is a historical region on the border between Central and Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast.

From the Hungarian Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, conquest of the Carpathian Basin ...

from Czechoslovakia. On 30 November, Czechoslovakia ceded to Poland small patches of land in the Spiš

Spiš ( ; or ; ) is a region in north-eastern Slovakia, with a very small area in south-eastern Poland (more specifically encompassing 14 former Slovak villages). Spiš is an informal designation of the territory, but it is also the name of one ...

and Orava regions. In March 1939, the First Slovak Republic, a German puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its ord ...

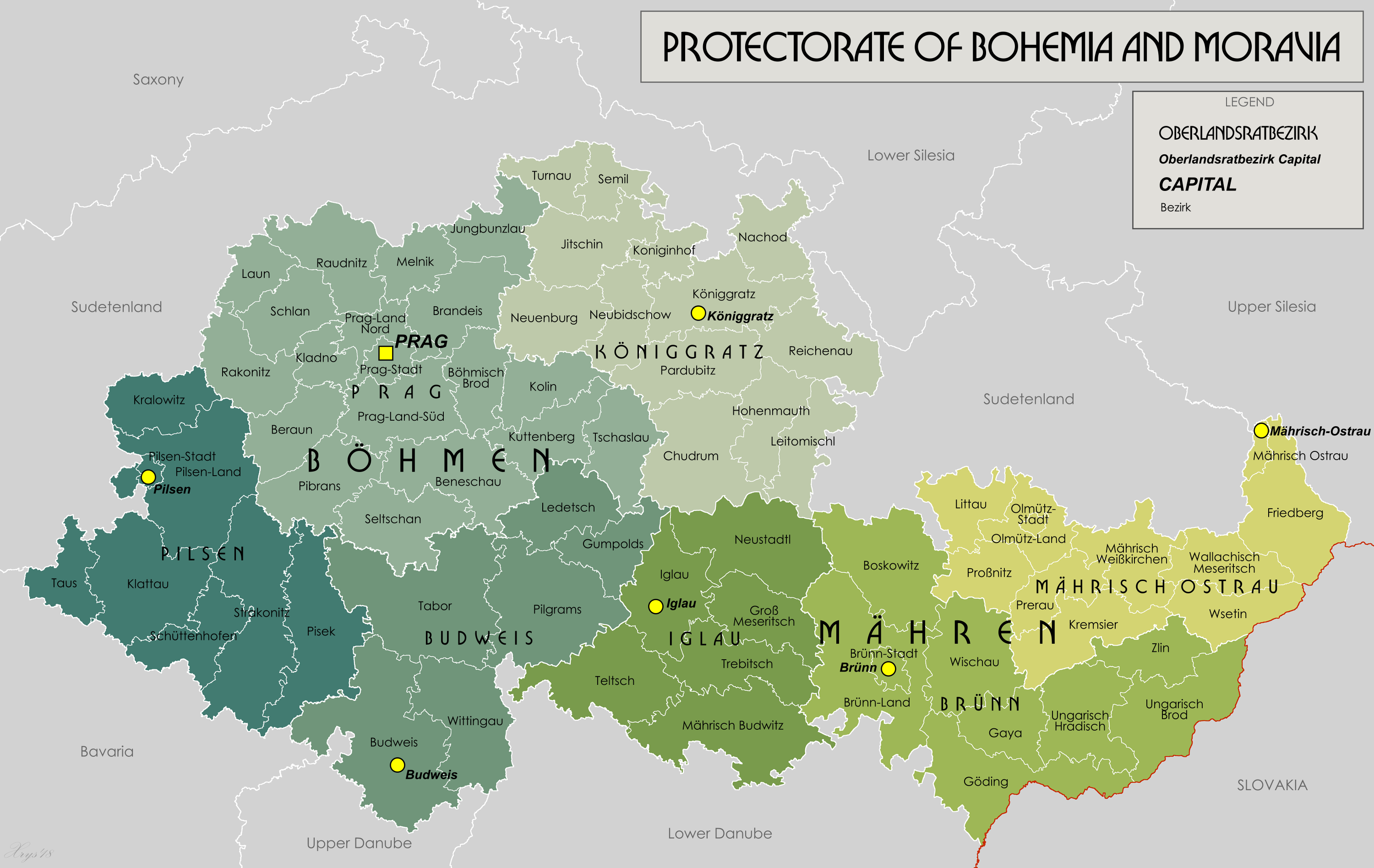

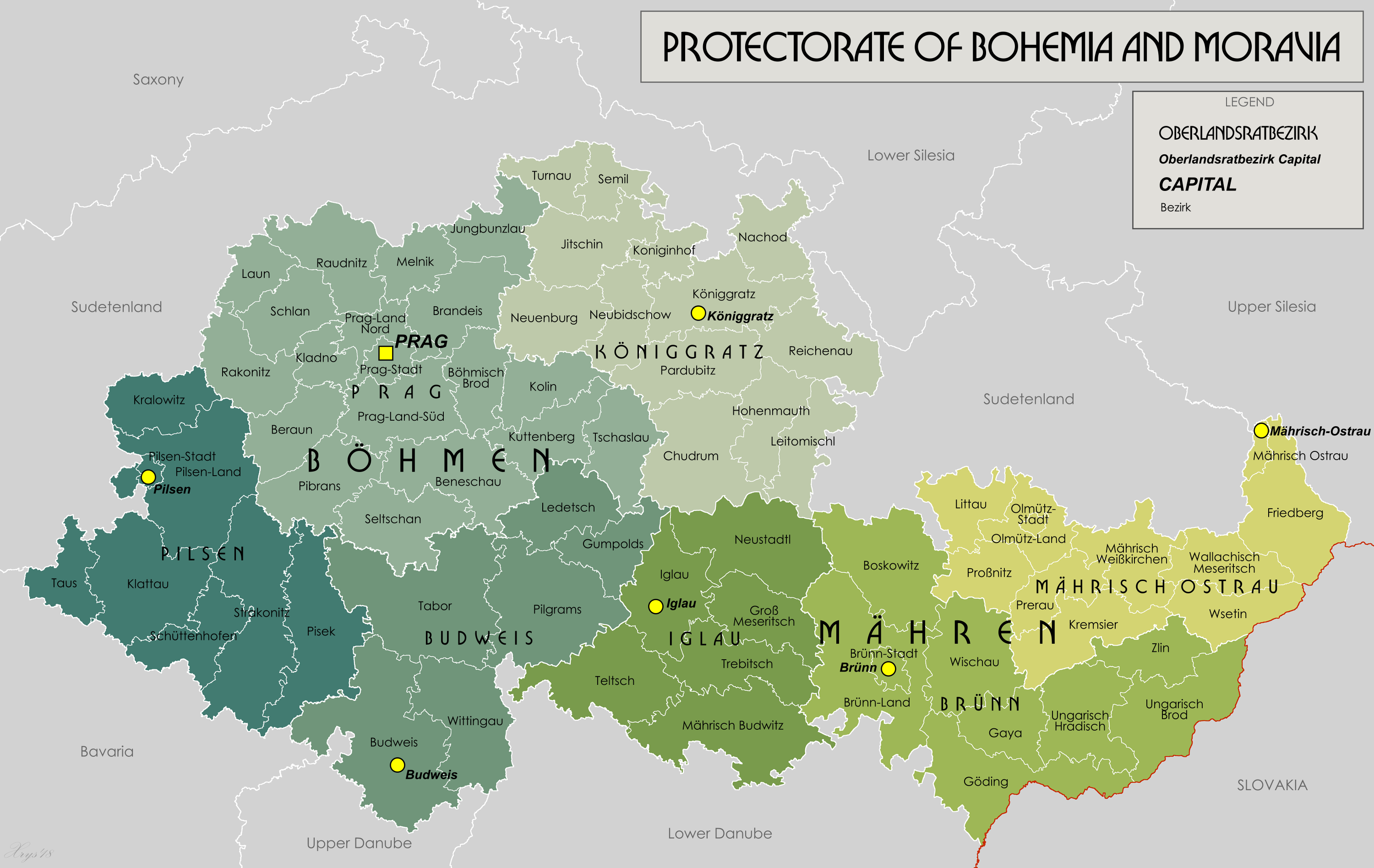

, proclaimed its independence. Shortly afterwards, Hitler reneged on his promise to respect the integrity of Czechoslovakia by occupying the remainder of the country and creating the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was a partially-annexation, annexed territory of Nazi Germany that was established on 16 March 1939 after the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945), German occupation of the Czech lands. The protector ...

. The conquered nation's military arsenal played an important role in Germany's invasions of Poland and France in 1939 and 1940.

Much of Europe celebrated the Munich Agreement, as they considered it a way to prevent a major war on the continent. Hitler announced that it was his last territorial claim in Northern Europe. Today, the Munich Agreement is regarded as a failed act of appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

, and the term has become "a byword for the futility of appeasing expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who ...

totalitarian states."

History

Background

Demands for autonomy

The

The First Czechoslovak Republic

The First Czechoslovak Republic, often colloquially referred to as the First Republic, was the first Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovak state that existed from 1918 to 1938, a union of ethnic Czechs and Slovaks. The country was commonly called Czechosl ...

was created in 1918 following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The Treaty of Saint-Germain recognized the independence of Czechoslovakia and the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (; ; ; ), often referred to in Hungary as the Peace Dictate of Trianon or Dictate of Trianon, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference. It was signed on the one side by Hungary ...

defined the borders of the new state, which was divided into the regions of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

and Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

in the west and Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus'

Transcarpathia (, ) is a historical region on the border between Central and Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast.

From the Hungarian Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, conquest of the Carpathian Basin ...

in the east, including more than three million Germans, 22.95% of the total population of the country. They lived mostly in border regions of the historical Czech Lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands (, ) is a historical-geographical term which denotes the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia out of which Czechoslovakia, and later the Czech Republic and Slovakia, were formed. ...

for which they coined the new name Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

, which bordered on Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and the newly created country of Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

.

The Sudeten Germans were not consulted on whether they wished to be citizens of Czechoslovakia. Although the constitution guaranteed equality for all citizens, there was a tendency among political leaders to transform the country "into an instrument of Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

and Slovak nationalism." Some progress was made to integrate the Germans and other minorities, but they continued to be underrepresented in the government and the army. Moreover, the Great Depression, beginning in 1929, impacted the highly industrialized and export-oriented Sudeten Germans more than it did the Czech and Slovak populations. By 1936, 60 percent of the unemployed people in Czechoslovakia were Germans.

In 1933, Sudeten German leader Konrad Henlein founded the Sudeten German Party (SdP), which was "militant, populist, and openly hostile" to the Czechoslovak government. It soon captured two-thirds of the vote in districts with a heavy German population. Historians differ as to whether the SdP was a Nazi front organisation from its beginning, or if it evolved into one.Eleanor L. Turk. ''The History of Germany''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1999. . p. 123. By 1935, the SdP was the second-largest political party in Czechoslovakia as German votes concentrated on this party, and Czech and Slovak votes were spread among several parties.

Shortly after the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, ), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "German Question, Greater Germany") arose after t ...

'' of Austria to Germany, Henlein met with Hitler in Berlin on 28 March 1938, and was instructed to make demands unacceptable to the democratic Czechoslovak government, led by President Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1939 to 1948. During the first six years of his second stint, he led the Czec ...

. On 24 April, the SdP issued a series of demands known as the Karlsbader Programm. Henlein demanded autonomy for Germans in Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak government responded by saying that it was willing to provide more minority rights

Minority rights are the normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or gender and sexual minorities, and also the collective rights accorded to any minority group.

Civil-rights movements oft ...

to the German minority but was initially reluctant to grant autonomy. The SdP gained 88% of the ethnic German votes in May 1938.

With tension high between the Germans and the Czechoslovak government, Beneš, on 15 September 1938, secretly offered to give of Czechoslovakia to Germany, in exchange for a German agreement to admit 1.5 to 2.0 million Sudeten Germans expelled by Czechoslovakia. Hitler did not reply.

Sudeten crisis

As the previousappeasement of Hitler

Appeasement, in an international context, is a diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power with intention to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign p ...

had shown, France and Britain were intent on avoiding war. The French government did not wish to face Germany alone and took its lead from British Conservative government of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

. He considered the Sudeten German grievances justified and believed Hitler's intentions to be limited. Both Britain and France, therefore, advised Czechoslovakia to accede to Germany's demands. Beneš resisted and, on 19 May, initiated a partial mobilization

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

in response to a possible German invasion.

On 20 May, Hitler presented his generals with a draft plan of attack on Czechoslovakia that was codenamed Operation Green. He insisted that he would not "smash Czechoslovakia" militarily without "provocation", "a particularly favourable opportunity" or "adequate political justification." On 28 May, Hitler called a meeting of his service chiefs, ordered an acceleration of U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

construction and brought forward the construction of his new battleships, '' Bismarck'' and ''Tirpitz Tirpitz may refer to:

People

* Alfred von Tirpitz (1849–1930), German admiral

** Tirpitz Plan, a plan for Germany to achieve world power status through naval power

Ships

* German battleship ''Tirpitz'', a World War II-era Bismarck-class ...

,'' to spring 1940. He demanded that the increase in the firepower of the battleships '' Scharnhorst'' and '' Gneisenau'' be accelerated. While recognizing that this would still be insufficient for a full-scale naval war with Britain, Hitler hoped it would be a sufficient deterrent. Ten days later, Hitler signed a secret directive for war against Czechoslovakia to begin no later than 1 October.

On 22 May, Juliusz Łukasiewicz

Juliusz Łukasiewicz (; May 6, 1892 – April 6, 1951) was a Polish diplomat, an ambassador of Poland to the Soviet Union and France, and a Polish Freemason.Cezary Leżeński, Legiony to braterska nuta... czyli od Legionów do masonów, Wolnomul ...

, the Polish ambassador to France, told French Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet that if France moved against Germany to defend Czechoslovakia, "We shall not move." Łukasiewicz also told Bonnet that Poland would oppose any attempt by Soviet forces to defend Czechoslovakia from Germany. Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical Party (France), Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, who was the Prime Minister of France in 1933, 1934 and again from 1938 to 1940. he signed the Munich Agreeme ...

told Jakob Suritz, the Soviet ambassador to France, "Not only can we not count on Polish support but we have no faith that Poland will not strike us in the back." However, the Polish government indicated multiple times (in March 1936 and May, June and August 1938) that it was prepared to fight Germany if the French decided to help Czechoslovakia: "Beck's proposal to Bonnet, his statements to Ambassador Drexel Biddle, and the statement noted by Vansittart, show that the Polish foreign minister was, indeed, prepared to carry out a radical change of policy if the Western powers decided on war with Germany. However, these proposals and statements did not elicit any reaction from British and French governments that were bent on averting war by appeasing Germany."

Hitler's adjutant, Fritz Wiedemann, recalled after the war that he was "very shocked" by Hitler's new plans to attack Britain and France three to four years after "deal ngwith the situation" in Czechoslovakia. General

Hitler's adjutant, Fritz Wiedemann, recalled after the war that he was "very shocked" by Hitler's new plans to attack Britain and France three to four years after "deal ngwith the situation" in Czechoslovakia. General Ludwig Beck

Ludwig August Theodor Beck (; 29 June 1880 – 20 July 1944) was a German general who served as Chief of the German General Staff from 1933 to 1938. Beck was one of the main conspirators of the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

...

, chief of the German general staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

, noted that Hitler's change of heart in favour of quick action was because Czechoslovak defences were still being improvised, which would no longer be the case two to three years later, and British rearmament would not come into effect until 1941 or 1942. General Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl (; born Alfred Josef Baumgärtler; 10 May 1890 – 16 October 1946) was a German Wehrmacht Heer, Army ''Generaloberst'' (the rank was equal to a four-star full general) and War crime, war criminal, who served as th ...

noted in his diary that the partial Czechoslovak mobilization of 21 May had led Hitler to issue a new order for Operation Green on 30 May and that it was accompanied by a covering letter from Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal who held office as chief of the (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's armed forces, during World War II. He signed a number of criminal ...

that stated that the plan must be implemented by 1 October at the very latest.

In the meantime, the British government demanded that Beneš request a mediator. Not wishing to sever his government's ties with Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, Beneš reluctantly accepted. The British appointed Lord Runciman

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford, (19 November 1870 – 14 November 1949), was a prominent Liberal Party (UK), Liberal and later National Liberal Party (UK, 1931), National Liberal politician in the United Kingdom. His 19 ...

, a former Liberal cabinet minister, who arrived in Prague on 3 August with instructions to persuade Beneš to agree to a plan acceptable to the Sudeten Germans. On 20 July, Bonnet told the Czechoslovak ambassador in Paris that while France would declare its support in public to help the Czechoslovak negotiations, it was not prepared to go to war over Sudetenland. In August, the German press was full of stories alleging Czechoslovak atrocities against Sudeten Germans, with the intention of forcing the West into putting pressure on the Czechoslovaks to make concessions. Hitler hoped that the Czechoslovaks would refuse and that the West would then feel morally justified in leaving the Czechoslovaks to their fate. In August, Germany sent 750,000 soldiers along the border of Czechoslovakia, officially as part of army maneuvres. On 4 or 5 September, Beneš submitted the Fourth Plan, granting nearly all the demands of the agreement. The Sudeten Germans were under instruction from Hitler to avoid a compromise, and the SdP held demonstrations that provoked a police action in Ostrava

Ostrava (; ; ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 283,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four rivers: Oder, Opava (river), Opa ...

on 7 September, in which two of their parliamentary deputies were arrested. The Sudeten Germans used the incident and false allegations of other atrocities as an excuse to break off further negotiations.

On 12 September, Hitler made a speech at a Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg on the Sudeten crisis condemning the actions of the government of Czechoslovakia. Hitler denounced Czechoslovakia as being a fraudulent state that was in violation of international law's emphasis of national self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, claiming it was a Czech hegemony although the Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

, the Slovaks

The Slovaks ( (historical Sloveni ), singular: ''Slovák'' (historical: ''Sloven'' ), feminine: ''Slovenka'' , plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history ...

, the Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an Ethnicity, ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common Culture of Hungary, culture, Hungarian language, language and History of Hungary, history. They also have a notable presence in former pa ...

, the Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

and the Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

of the country actually wanted to be in a union with the Czechs.Adolf Hitler, Max Domarus. ''The Essential Hitler: Speeches and Commentary''. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2007. . p. 626. Hitler accused Beneš of seeking to gradually exterminate the Sudeten Germans and claimed that since Czechoslovakia's creation, over 600,000 Germans had been intentionally forced out of their homes under the threat of starvation if they did not leave.Adolf Hitler, Max Domarus. ''The Essential Hitler: Speeches and Commentary''. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2007. . p. 627. He alleged that Beneš's government was persecuting Germans along with Hungarians, Poles, and Slovaks and accused Beneš of threatening the nationalities with being branded traitors if they were not loyal to the country. He stated that he, as the head of state of Germany, would support the right of the self-determination of fellow Germans in the Sudetenland. He condemned Beneš for his government's recent execution of several German protesters. He accused Beneš of being belligerent and threatening behaviour towards Germany which, if war broke out, would result in Beneš forcing Sudeten Germans to fight against their will against Germans from Germany. Hitler accused the government of Czechoslovakia of being a client regime

A client state in the context of international relations is a state that is economically, politically, and militarily subordinated to a more powerful controlling state. Alternative terms for a ''client state'' are satellite state, associated stat ...

of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, claiming that the French Minister of Aviation Pierre Cot had said, "We need this state as a base from which to drop bombs with greater ease to destroy Germany's economy and its industry."

Berchtesgaden meeting

On 13 September, after internal violence and disruption in Czechoslovakia ensued, Chamberlain asked Hitler for a personal meeting to find a solution to avert a war. Chamberlain decided to do this after conferring with his advisorsLord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He h ...

, Sir John Simon, and Sir Samuel Hoare. The meeting was announced at a special press briefing at 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London is the official residence and office of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. Colloquially known as Number 10, the building is located in Downing Street, off Whitehall in th ...

, and led to a swell of optimism in British public opinion. Chamberlain arrived by a chartered British Airways

British Airways plc (BA) is the flag carrier of the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in London, England, near its main Airline hub, hub at Heathrow Airport.

The airline is the second largest UK-based carrier, based on fleet size and pass ...

Lockheed Electra in Germany on 15 September and then arrived at Hitler's residence in Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden () is a municipality in the district Berchtesgadener Land, Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, near the border with Austria, south of Salzburg and southeast of Munich. It lies in the Berchtesgaden Alps. South of the town, the Be ...

for the meeting.Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. ''Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings''. New York: Enigma Books, 2008. . p. 71. The flight was one of the first times a head of state or diplomatic official flew to a diplomatic meeting in an airplane

An airplane (American English), or aeroplane (Commonwealth English), informally plane, is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, Propeller (aircraft), propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a vari ...

, as the tense situation left little time to take a train

A train (from Old French , from Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ... , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles th ...

or boat

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size or capacity, its shape, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically used on inland waterways s ...

. Henlein flew to Germany on the same day. That day, Hitler and Chamberlain held discussions in which Hitler insisted that the Sudeten Germans must be allowed to exercise the right of national self-determination and be able to join Sudetenland with Germany. Hitler repeatedly falsely claimed that the Czechoslovak government had killed 300 Sudeten Germans. Hitler also expressed concern to Chamberlain about what he perceived as British "threats." Chamberlain responded that he had not issued "threats" and in frustration asked Hitler "Why did I come over here to waste my time?" Hitler responded that if Chamberlain was willing to accept the self-determination of the Sudeten Germans, he would be willing to discuss the matter. Hitler also convinced Chamberlain that he did not truly wish to destroy Czechoslovakia, but that he believed that upon a German annexation of the Sudetenland the country's minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

would each secede and cause the country to collapse. Chamberlain and Hitler held discussions for three hours, and the meeting adjourned. Chamberlain flew back to Britain and met with his cabinet to discuss the issue.

After the meeting, Daladier flew to London on 16 September to meet with British officials to discuss a course of action. The situation in Czechoslovakia became tenser that day, with the Czechoslovak government issuing an arrest warrant for Henlein, who had arrived in Germany a day earlier to take part in the negotiations.Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. ''Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings''. New York: Enigma Books, 2008. . p. 72. The French proposals ranged from waging war against Germany to supporting the Sudetenland being ceded to Germany. The discussions ended with a firm British-French plan in place. Britain and France demanded that Czechoslovakia cede to Germany all territories in which the German population represented over 50% of the Sudetenland's total population. In exchange for that concession, Britain and France would guarantee the independence of Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia rejected the proposed solution.

On 17 September 1938 Hitler ordered the establishment of '' Sudetendeutsches Freikorps'', a paramilitary organization that took over the structure of Ordnersgruppe, an organization of ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia

German Bohemians ( ; ), later known as Sudeten Germans ( ; ), were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part of Czechoslovakia. Before 1945, over three million German Bohemians constitu ...

that had been dissolved by the Czechoslovak authorities the previous day due to its implication in a large number of terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

activities. The organization was sheltered, trained and equipped by German authorities and conducted cross-border terrorist operations into Czechoslovak territory. Relying on the Convention for the Definition of Aggression, Czechoslovak president Edvard Beneš and the government-in-exile

A government-in-exile (GiE) is a political group that claims to be the legitimate government of a sovereign state or semi-sovereign state, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile usu ...

later regarded 17 September 1938 as the beginning of the undeclared German-Czechoslovak war. This understanding has been assumed also by the contemporary Czech Constitutional court. ''Stran interpretace "kdy země vede válku", obsažené v čl. I Úmluvy o naturalizaci mezi Československem a Spojenými státy, publikované pod č. 169/1929 Sb. za účelem zjištění, zda je splněna podmínka státního občanství dle restitučních předpisů, Ústavní soud vychází z již v roce 1933 vypracované definice agrese Společnosti národů, která byla převzata do londýnské Úmluvy o agresi (CONVENITION DE DEFINITION DE L'AGRESSION), uzavřené dne 4. 7. 1933 Československem, dle které není třeba válku vyhlašovat (čl. II bod 2) a dle které je třeba za útočníka považovat ten stát, který první poskytne podporu ozbrojeným tlupám, jež se utvoří na jeho území a jež vpadnou na území druhého státu (čl. II bod 5). V souladu s nótou londýnské vlády ze dne 22. 2. 1944, navazující na prohlášení prezidenta republiky ze dne 16. 12. 1941 dle § 64 odst. 1 bod 3 tehdejší Ústavy, a v souladu s citovaným čl. II bod 5 má Ústavní soud za to, že dnem, kdy nastal stav války, a to s Německem, je den 17. 9. 1938, neboť tento den na pokyn Hitlera došlo k utvoření "Sudetoněmeckého svobodného sboru" (Freikorps) z uprchnuvších vůdců Henleinovy strany a několik málo hodin poté už tito vpadli na československé území ozbrojeni německými zbraněmi.'' In the following days, Czechoslovak forces suffered over 100 personnel killed in action, hundreds wounded and over 2,000 abducted to Germany.

On 18 September, Italy's ''Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word , 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 192 ...

'' Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

made a speech in Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

, Italy, where he declared "If there are two camps, for and against Prague, let it be known that Italy has chosen its side", with the clear implication being that Mussolini supported Germany in the crisis.

On 20 September, German opponents within the military met to discuss the final plans of a plot they had developed to overthrow the Nazi regime. The meeting was led by General Hans Oster

''Generalmajor'' Hans Paul Oster (9 August 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a general in the ''Wehrmacht'' and a leading figure of the anti-Nazi German resistance from 1938 to 1943. As deputy head of the counter-espionage bureau in the ''Abwehr'' (Ge ...

, the deputy head of the ''Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

'' (Germany's counter-espionage

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting ac ...

agency). Other members included Captain , and other military officers leading the planned coup d'etat met at the meeting.Nigel Jones. ''Countdown to Valkyrie: The July Plot to Assassinate Hitler''. pp. 73–74. On 22 September, Chamberlain, about to board his plane to go to Germany for further talks at Bad Godesberg, told the press who met him there that "My objective is peace in Europe, I trust this trip is the way to that peace." Chamberlain arrived in Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, where he received a lavish grand welcome with a German band playing "God Save the King

"God Save the King" ("God Save the Queen" when the monarch is female) is ''de facto'' the national anthem of the United Kingdom. It is one of national anthems of New Zealand, two national anthems of New Zealand and the royal anthem of the Isle ...

" and Germans giving Chamberlain flowers and gifts. Chamberlain had calculated that fully accepting German annexation of all of the Sudetenland with no reductions would force Hitler to accept the agreement. Upon being told of this, Hitler responded "Does this mean that the Allies have agreed with Prague's approval to the transfer of the Sudetenland to Germany?", Chamberlain responded "Precisely", to which Hitler responded by shaking his head, saying that the Allied offer was insufficient. He told Chamberlain that he wanted Czechoslovakia to be completely dissolved and its territories redistributed to Germany, Poland, and Hungary, and told Chamberlain to take it or leave it. Chamberlain was shaken by this statement. Hitler went on to tell Chamberlain that since their last meeting on the 15th, Czechoslovakia's actions, which Hitler claimed included killings of Germans, had made the situation unbearable for Germany.

Later in the meeting, a deception was undertaken to influence and put pressure on Chamberlain: one of Hitler's aides entered the room to inform Hitler of more Germans being killed in Czechoslovakia, to which Hitler screamed in response "I will avenge every one of them. The Czechs must be destroyed." The meeting ended with Hitler refusing to make any concessions to the Allies' demands. Later that evening, Hitler grew worried that he had gone too far in pressuring Chamberlain, and telephoned Chamberlain's hotel suite, saying that he would accept annexing only the Sudetenland, with no designs on other territories, provided that Czechoslovakia begin the evacuation of ethnic Czechs from the German majority territories by 26 September at 8:00am. After being pressed by Chamberlain, Hitler agreed to have the ultimatum set for 1 October (the same date that Operation Green was set to begin).Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. ''Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings''. New York: Enigma Books, 2008. . p. 73. Hitler then said to Chamberlain that this was one concession that he was willing to make to the Prime Minister as a "gift" out of respect for the fact that Chamberlain had been willing to back down somewhat on his earlier position. Hitler went on to say that upon annexing the Sudetenland, Germany would hold no further territorial claims upon Czechoslovakia and would enter into a collective agreement to guarantee the borders of Germany and Czechoslovakia.

A new Czechoslovak cabinet, under General Jan Syrový, was installed and on 23 September a decree of general mobilization was issued which was accepted by the public with a strong enthusiasm – within 24 hours, one million men joined the army to defend the country. The Czechoslovak Army, modern, experienced and possessing an excellent system of frontier fortifications, was prepared to fight. The Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

announced its willingness to come to Czechoslovakia's assistance, provided that the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

would be able to cross Polish and Romanian territory. Both countries refused to allow the Soviet army to use their territories.

In the early hours of 24 September, Hitler issued the Godesberg Memorandum, which demanded that Czechoslovakia cede the Sudetenland to Germany no later than 28 September, with plebiscites to be held in unspecified areas under the supervision of German and Czechoslovak forces. The memorandum also stated that if Czechoslovakia did not agree to the German demands by 2 pm on 28 September, Germany would take the Sudetenland by force. On the same day, Chamberlain returned to Britain and announced that Hitler demanded the annexation of the Sudetenland without delay. The announcement enraged those in Britain and France who wanted to confront Hitler once and for all, even if it meant war, and its supporters gained strength. The Czechoslovak Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Jan Masaryk, was elated upon hearing of the support for Czechoslovakia from British and French opponents of Hitler's plans, saying "The nation of Saint Wenceslas will never be a nation of slaves."

On 25 September, Czechoslovakia agreed to the conditions previously agreed upon by Britain, France, and Germany. The next day, however, Hitler added new demands, insisting that the claims of ethnic Germans in Poland and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

also be satisfied.

On 26 September, Chamberlain sent Sir Horace Wilson to carry a personal letter to Hitler declaring that the Allies wanted a peaceful resolution to the Sudeten crisis. Later that evening, Hitler made his response in a speech at the Berlin Sportpalast; he claimed that the Sudetenland was "the last territorial demand I have to make in Europe" and gave Czechoslovakia a deadline of 28 September at 2:00 pm to cede the Sudetenland to Germany or face war. At this point the British government began to make war preparations, and the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

was reconvened from a parliamentary recess.

On 27 September 1938, when negotiations between Hitler and Chamberlain were strained, Chamberlain addressed the British people, saying, in particular: "How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing."

On 28 September at 10:00 am, four hours before the deadline and with no agreement to Hitler's demand by Czechoslovakia, the British ambassador to Italy, Lord Perth, called Italy's Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944), was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law ...

to request an urgent meeting. Perth informed Ciano that Chamberlain had instructed him to request that Mussolini enter the negotiations and urge Hitler to delay the ultimatum. At 11:00 am, Ciano met Mussolini and informed him of Chamberlain's proposition; Mussolini agreed with it and responded by telephoning Italy's ambassador to Germany and told him "Go to the Fuhrer at once, and tell him that whatever happens, I will be at his side, but that I request a twenty-four-hour delay before hostilities begin. In the meantime, I will study what can be done to solve the problem." Hitler received Mussolini's message while in discussions with the French ambassador. Hitler responded "My good friend, Benito Mussolini, has asked me to delay for twenty-four hours the marching orders of the German army, and I agreed." Of course, this was no concession, as the invasion date was set for 1 October 1938.Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. ''Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings''. New York: Enigma Books, 2008. . p. 74. Upon speaking with Chamberlain, Lord Perth gave Chamberlain's thanks to Mussolini as well as Chamberlain's request that Mussolini attend a four-power conference of Britain, France, Germany, and Italy in Munich on 29 September to settle the Sudeten problem prior to the deadline of 2:00 pm. Mussolini agreed. Hitler's only request was to make sure that Mussolini be involved in the negotiations at the conference. Nevile Henderson

Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson (10 June 1882 – 30 December 1942) was a British diplomat who served as the ambassador of the United Kingdom to Nazi Germany, Germany from 1937 to 1939.

Early life and education

Henderson was born at Sedgwick, Wes ...

, Alexander Cadogan, and Chamberlain's personal secretary Lord Dunglass passed the news of the conference to Chamberlain while he was addressing Parliament, and Chamberlain suddenly announced the conference and his acceptance to attend at the end of the speech to cheers. When United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

learned the conference had been scheduled, he telegraphed Chamberlain, "Good man."

Resolution

Discussions began at the Führerbau immediately after Chamberlain and Daladier arrived, giving them little time to consult. The meeting was held in English, French, and German. A deal was reached on 29 September, and at about 1:30 a.m. on 30 September 1938,Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

, Neville Chamberlain, Benito Mussolini and Édouard Daladier signed the Munich Agreement. The agreement was officially introduced by Mussolini although in fact the Italian plan was nearly identical to the Godesberg proposal: the German army was to complete the occupation of the Sudetenland by 10 October, and an international commission would decide the future of other disputed areas.Susan Bindoff Butterworth, "Daladier and the Munich crisis: A reappraisal." ''Journal of Contemporary History'' 9.3 (1974): 191–216.

Czechoslovakia was informed by Britain and France that it could either resist Nazi Germany alone or submit to the prescribed annexations. The Czechoslovak government, realizing the hopelessness of fighting the Nazis alone, reluctantly capitulated (30 September) and agreed to abide by the agreement. The settlement gave Germany the Sudetenland starting 10 October, and ''de facto'' control over the rest of Czechoslovakia as long as Hitler promised to go no further. On 30 September after some rest, Chamberlain went to Hitler's apartment in the Prinzregentenstraße and asked him to sign a statement calling the Anglo-German Naval Agreement "symbolic of the desire of our two countries never to go to war with one another again." After Hitler's interpreter translated it for him, he happily agreed.

On 30 September, upon his return to Britain, Chamberlain delivered his controversial " peace for our time" speech to crowds in London.

Reactions

Immediate response

= Czechoslovakia

= The Czechoslovaks were dismayed with the Munich settlement. They were not invited to the conference and felt they had been betrayed by the British and French governments. ManyCzechs

The Czechs (, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common Bohemia ...

and Slovaks refer to the Munich Agreement as the Munich Diktat

A diktat (, ) is a statute, harsh penalty or settlement imposed upon a defeated party by the victor, or a dogmatic decree. The term has acquired a pejorative sense, to describe a set of rules dictated by a foreign power or an unpopular local power ...

(; ). The phrase " Munich Betrayal" (; ) is also used because the military alliance Czechoslovakia had with France proved useless. This was also reflected by the fact that especially the French government had expressed the view that Czechoslovakia would be considered as being responsible for any resulting European war should the Czechoslovak Republic defend itself with force against German incursions.

The slogan " About us, without us!" (; ) summarizes the feelings of the people of Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

and the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

) towards the agreement. With Sudetenland gone to Germany, Czecho-Slovakia (as the state was now renamed) lost its defensible border with Germany and the Czechoslovak border fortifications. Without them its independence became more nominal than real. Czechoslovakia also lost 70 per cent of its iron/steel industry, 70 per cent of its electrical power and 3.5 million citizens to Germany as a result of the settlement. The Sudeten Germans celebrated what they saw as their liberation. The imminent war, it seemed, had been avoided.

The Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

, Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

, took to pen and pulpit in defense of his surrogate homeland proclaiming his pride at being a Czechoslovak citizen and praising the republic's achievements. He attacked a "Europe ready for slavery" writing that "The Czechoslovak people is ready to take up a fight for liberty and transcends its own fate" and "It is too late for the British government to save the peace. They have lost too many opportunities." President Beneš of Czechoslovakia was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

in 1939.

= Germany

= Though the British and French were pleased, a British diplomat in Berlin claimed he had been informed by a member of Hitler's entourage that soon after the meeting with Chamberlain, Hitler had furiously said: "Gentlemen, this has been my first international conference and I can assure you that it will be my last." On another occasion, he had been heard saying of Chamberlain: "If ever that silly old man comes interfering here again with his umbrella, I'll kick him downstairs and jump on his stomach in front of the photographers."Richard Overy

Richard James Overy (born 23 December 1947) is a British historian who has published on the history of World War II and Nazi Germany. In 2007, as ''The Times'' editor of ''Complete History of the World'', he chose the 50 key dates of world his ...

, 'Germany, "Domestic Crisis" and War in 1939', ''Past & Present'' No. 116 (Aug., 1987), p. 163, n. 74. In one of his public speeches after Munich, Hitler declared: "Thank God we have no umbrella politicians in this country."

Hitler felt cheated of the limited war against the Czechs which he had been aiming for all summer. In early October, Chamberlain's press secretary asked for a public declaration of German friendship with Britain to strengthen Chamberlain's domestic position; Hitler instead delivered speeches denouncing Chamberlain's "governessy interference." In August 1939, shortly before the invasion of Poland, Hitler told his generals: "Our enemies are men below average, not men of action, not masters. They are little worms. I saw them at Munich."

Before the Munich Agreement, Hitler's determination to invade Czechoslovakia on 1 October 1938 had provoked a major crisis in the German command structure. The Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck, protested in a lengthy series of memos that it would start a

Hitler felt cheated of the limited war against the Czechs which he had been aiming for all summer. In early October, Chamberlain's press secretary asked for a public declaration of German friendship with Britain to strengthen Chamberlain's domestic position; Hitler instead delivered speeches denouncing Chamberlain's "governessy interference." In August 1939, shortly before the invasion of Poland, Hitler told his generals: "Our enemies are men below average, not men of action, not masters. They are little worms. I saw them at Munich."

Before the Munich Agreement, Hitler's determination to invade Czechoslovakia on 1 October 1938 had provoked a major crisis in the German command structure. The Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck, protested in a lengthy series of memos that it would start a world war

A world war is an international War, conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I ...

that Germany would lose, and urged Hitler to put off the projected conflict. Hitler called Beck's arguments against war "''kindische Kräfteberechnungen''" ("childish force calculations"). On 4 August 1938, a secret Army meeting was held. Beck read his lengthy report to the assembled officers. They all agreed something had to be done to prevent certain disaster. Beck hoped they would all resign together but no one resigned except Beck. His replacement, General Franz Halder

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German general and the chief of staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres, Army High Command (OKH) in Nazi Germany from 1938 until September 1942. During World War II, he directed the planning and i ...

, sympathized with Beck and they were both recruited into Hans Oster

''Generalmajor'' Hans Paul Oster (9 August 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a general in the ''Wehrmacht'' and a leading figure of the anti-Nazi German resistance from 1938 to 1943. As deputy head of the counter-espionage bureau in the ''Abwehr'' (Ge ...

's September Conspiracy which planned to arrest Hitler the moment he gave the invasion order.

This plan would only work if Britain issued a strong warning and a letter to the effect that they would fight to preserve Czechoslovakia. This would help to convince the German people that certain defeat awaited Germany. Agents were therefore sent to England to tell Chamberlain that an attack on Czechoslovakia was planned, and of their intention to overthrow Hitler if this occurred. The proposal was rejected by the British Cabinet and no such letter was issued. Accordingly, the proposed removal of Hitler did not go ahead.

On 7 October 1938, Hitler visited the Sudeten territories. He arrived by train in Neustadt (now Prudnik

Prudnik (, , , ) is a town in southern Poland, located in the southern part of Opole Voivodeship near the border with the Czech Republic. It is the administrative seat of Prudnik County and Gmina Prudnik. Its population numbers 21,368 inhabitant ...

, Poland), a town right next to the former Czechoslovak border, and then travelled to Město Albrechtice, Krnov

Krnov (; , or ''Krnów'') is a town in Bruntál District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 23,000 inhabitants.

Administrative division

Krnov consists of three municipal parts (in brackets population according to ...

, Bruntál

Bruntál (; ) is a town in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 15,000 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected as an Cultural monument (Czech Republic)#Monument zones, urban monument zon ...

, and Zlaté Hory.

= Britain and France

= The agreement was generally applauded. Prime Minister Daladier of France did not believe, as one scholar put it, that a European War was justified "to maintain three million Germans under Czech sovereignty."Gallup Poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American multinational analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Gallup provides analytics and man ...

s in Britain, France, and the United States indicated that the majority of people supported the agreement. President Beneš of Czechoslovakia was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1939.Douglas, pp. 14–15

''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' headline on the Munich agreement read "Hitler gets less than his Sudeten demands" and reported that a "joyful crowd" hailed Daladier on his return to France and that Chamberlain was "wildly cheered" on his return to Britain.

In France, the only political party to oppose the Munich Agreement was the Communist Party.

The British population had expected an imminent war, and the "statesman-like gesture" of Chamberlain was at first greeted with acclaim. He was greeted as a hero by the royal family and invited on the balcony at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

before he had presented the agreement to the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

. The generally positive reaction quickly soured, despite royal patronage. However, there was opposition from the start. Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

and the Labour Party opposed the agreement, in alliance with two Conservative MPs, Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, (22 February 1890 – 1 January 1954), known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician and diplomat who was also a military and political historian and writer.

First elected to Parl ...

and Vyvyan Adams, who had been seen up to then as a reactionary element in the Conservative Party.

Daladier believed that Hitler's ultimate goals were a threat. He told the British in a late April 1938 meeting that Hitler's real long-term aim was to secure "a domination of the Continent in comparison with which the ambitions of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

were feeble." He went on to say: "Today it is the turn of Czechoslovakia. Tomorrow it will be the turn of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

. When Germany has obtained the oil and wheat it needs, she will turn on the West. Certainly we must multiply our efforts to avoid war. But that will not be obtained unless Great Britain and France stick together, intervening in Prague for new concessions but declaring at the same time that they will safeguard the independence of Czechoslovakia. If, on the contrary, the Western Powers capitulate again they will only precipitate the war they wish to avoid." Perhaps discouraged by the arguments of French military leaders and civilian officials regarding their unprepared military and weak financial situation, and still traumatized by France's bloodbath in World War I, which he had personally witnessed, Daladier ultimately let Chamberlain have his way. On his return to Paris, Daladier, who had expected a hostile crowd, was acclaimed.

In the days following Munich, Chamberlain received more than 20,000 letters and telegrams of thanks, and gifts including 6000 assorted bulbs from grateful Dutch admirers and a cross from Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

.

=Poland

=Trans-Olza

Trans-Olza (, ; , ''Záolší''; ), also known as Trans-Olza Silesia (), is a territory in the Czech Republic which was disputed between Poland and Czechoslovakia during the Interwar Period. Its name comes from the Olza River.

The history of ...

from 1935. In summer 1938, Poland tried to organize guerrilla groups in the area. On 21 September, Poland officially requested a direct transfer of the area to its own control. Polish envoy to Prague Kazimierz Papée marked that the return of Cieszyn Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia, Těšín Silesia or Teschen Silesia ( ; or ; or ) is a historical region in south-eastern Silesia, centered on the towns of Cieszyn and Český Těšín and bisected by the Olza River. Since 1920 it has been divided betwe ...

will be a sign of a goodwill and the "redress of injustice" of 1920. Similar notes were sent to Paris and London with a request that Polish minority in Czechoslovakia should gain the same rights as Sudeten Germans. On the next day Beneš sent a letter to Polish president Ignacy Mościcki with a promise of "border's rectification", but the letter was delivered only on 26 September. The answer of Mościcki delivered on 27 September was evasive, but it was accompanied with the demand of Polish government to hand over two Trans-Olza counties immediately, as a prelude to ultimate settlement of the border dispute. Beneš's answer wasn't conclusive: he agreed to hand over the disputed territory to Poland but argued that it could not be done on the eve of the German invasion, because it would disrupt Czechoslovak preparations for war. Poles recognised the answer as playing for time.

Polish diplomatic actions were accompanied by placing army along the Czechoslovak border on 23–24 September and by giving an order to the so-called "battle units" of Trans-Olza Poles and the "Trans-Olza Legion", a paramilitary organisation that was made up of volunteers from all over Poland, to cross the border to Czechoslovakia and attack Czechoslovak units. The few who crossed, however, were repulsed by Czechoslovak forces and retreated to Poland.

The Polish ambassador in Germany learned about the results of Munich Conference on 30 September from Ribbentrop, who assured him that Berlin conditioned the guarantees for the remainder of Czechoslovakia on the fulfilment of Polish and Hungarian territorial demands. Polish foreign minister Józef Beck

Józef Beck (; 4 October 1894 – 5 June 1944) was a Polish statesman who served the Second Republic of Poland as a diplomat and military officer. A close associate of Józef Piłsudski, Beck is most famous for being Polish foreign minister in ...

was disappointed with such a turn of events. In his own words the conference was "an attempt by the directorate of great powers to impose binding decisions on other states (and Poland cannot agree on that, as it would then be reduced to a political object that others conduct at their will)." As a result, at 11:45 p.m. on 30 September, 11 hours after the Czechoslovak government accepted the Munich terms, Poland gave an ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government. It demanded the immediate evacuation of Czechoslovak troops and police and gave Prague time until noon the following day. At 11:45 a.m. on 1 October the Czechoslovak Foreign Ministry called the Polish ambassador in Prague and told him that Poland could have what it wanted but then requested a 24-hour delay. On 2 October, the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the Army, land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 110,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military histor ...

, commanded by General Władysław Bortnowski

Władysław Bortnowski (12 November 1891 – 21 November 1966) was a Polish historian, military commander and one of the highest ranking generals of the Polish Army, generals of the Polish Army. He is most famous for commanding the Pomorze Army ...

, annexed an area of 801.5 km2 with a population of 227,399 people. Administratively the annexed area was divided between Frysztat County and Cieszyn County.

The historian Dariusz Baliszewski wrote that during the annexation there was no co-operation between Polish and German troops, but there were cases of co-operation between Polish and Czech troops defending territory against Germans, for example in Bohumín

Bohumín (; , ) is a town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 20,000 inhabitants.

Administrative division

Bohumín consists of seven municipal parts (in brackets population according to the 202 ...

.

The Polish ultimatum finally led Beneš to decide, by his own account, to abandon any idea of resisting the settlement (Czechoslovakia would have been attacked on all sides).

The Germans were delighted with that outcome and were happy to give up the sacrifice of a small provincial rail centre to Poland in exchange for the ensuing propaganda benefits. It spread the blame of the partition of Czechoslovakia, made Poland a participant in the process and confused political expectations. Poland was accused of being an accomplice of Germany. However, there was no formal agreement between Poland and Germany about Czechoslovakia at any time.

The Chief of the General Staff of the Czechoslovak Army, General Ludvík Krejčí

Ludvík Krejčí (17 August 1890 – 9 February 1972) was a Czechoslovak army general and legionary of the First World War.

Biography Early life and World War I

He was born on 17 August 1890 in Brno-Tuřany, near Brno, as the youngest of eight ch ...

, reported on 29 September that "Our army will in about two days' time be in full condition to withstand an attack even by all Germany's forces together, provided Poland does not move against us."

Historians such as H.L. Roberts and Anna Cienciala have characterised Beck

Beck David Hansen (born Bek David Campbell; July 8, 1970), known mononymously as Beck, is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and record producer. He rose to fame in the early 1990s with his Experimental music, experimental and Lo-fi mus ...

's actions during the crisis as unfriendly to Czechoslovakia, but not actively seeking its destruction. Whilst Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

-era Polish historiography typically followed the line that Beck had been a "German Agent" and had collaborated with Germany, post-1956 historiography has generally rejected this characterisation.

=Hungary

= Hungary followed Polish request for transfer of territory with its own request on 22 September. Hungarian demands were ultimately fulfilled during the Vienna Arbitration on 2 November 1938.= Soviet Union

=Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

was upset by the results of the Munich conference. On 2 May 1935, France and the Soviet Union signed the Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance

The Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance was a bilateral treaty between France and the Soviet Union with the aim of enveloping Nazi Germany in 1935 to reduce the threat from Central Europe. It was pursued by Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet forei ...

with the aim of containing Nazi Germany's aggression. The Soviets, who had a mutual military assistance treaty with Czechoslovakia, felt betrayed by France, which also had a mutual military assistance treaty with Czechoslovakia. The British and French mostly used the Soviets as a threat to dangle over the Germans. Stalin concluded that the West had colluded with Hitler to hand over a country in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...