Mozambican War Of Independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mozambican War of Independence was an

Portugal's history since 1974

"The Portuguese Communist Party (PCP–Partido Comunista Português), which had courted and infiltrated the MFA from the very first days of the revolution, decided that the time was now right for it to seize the initiative. Much of the radical fervour that was unleashed following Spínola's coup attempt was encouraged by the PCP as part of their own agenda to infiltrate the MFA and steer the revolution in their direction.", Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril,

Mozambique

''The Catholic Encyclopaedia''. Retrieved on 10 March 2007 Portugal's influence in East Africa grew throughout the 16th century; it established several colonies known collectively as Portuguese East Africa. Slavery and gold became profitable for the Europeans; influence was largely exercised through individual settlers and there was no centralized administration.T. H. Henriksen, ''Remarks on Mozambique'', 1975, p. 11 By the 19th century, most of Africa fell under European colonial rule. Having lost control of the vast territory of

By the 19th century, most of Africa fell under European colonial rule. Having lost control of the vast territory of

Mozambique

, Encarta. Retrieved on 10 March 2007

Archived

1 November 2009. As a result, in an attempt to avoid a naval conflict with the superior

The Soviet Offensive in South Africa

'', airpower.maxwell, af.mil, 1983. Retrieved on 10 March 2007 Prior to the formation of FRELIMO, the Soviet position regarding the nationalist movements in Mozambique was confused. There were multiple independence movements, and they had no sure knowledge that any would succeed. The liberation movement's largely Marxist–Leninist principles and the eastern bloc's strategy of destabilization made Mozambican alliance with other left nations of the world seem like a foregone conclusion. Nationalist groups in Mozambique, like those across Africa during the period, received training and equipment from the Soviet Union. But leaders of the movement for independence also wanted to balance their support. As such, they lobbied for and received support from both eastern bloc and non-aligned nations upon its consolidation into FRELIMO. The movement was even initially supported by the U.S. government. In 1963, Mondlane met with Kennedy administration officials who later provided a $60,000 CIA subsidy in support of the movement. The Kennedy administration, however, rejected his request for military aid and by 1968 the Johnson administration severed all financial ties. Eduardo Mondlane's successor, future President of Mozambique,

At the war's outset, FRELIMO had little hope for a conventional military victory, with a mere 7,000 combatants against a far larger Portuguese force. Their hopes rested on urging the local populace to support the insurgency, in order to force a negotiated independence from Lisbon. Portugal fought its own version of protracted warfare, and a large military force was sent to quell the unrest, with troop numbers rising from 8,000 to 24,000 between 1964 and 1967.

The military wing of FRELIMO was commanded by Filipe Samuel Magaia, whose forces received training from

At the war's outset, FRELIMO had little hope for a conventional military victory, with a mere 7,000 combatants against a far larger Portuguese force. Their hopes rested on urging the local populace to support the insurgency, in order to force a negotiated independence from Lisbon. Portugal fought its own version of protracted warfare, and a large military force was sent to quell the unrest, with troop numbers rising from 8,000 to 24,000 between 1964 and 1967.

The military wing of FRELIMO was commanded by Filipe Samuel Magaia, whose forces received training from

In 1964, attempts at peaceful negotiation by FRELIMO were abandoned and, on 25 September, Eduardo Mondlane began to launch guerrilla attacks on targets in northern Mozambique from his base in Tanzania. FRELIMO soldiers, with logistical assistance from the local population, attacked the administrative post at Chai in the province of Cabo Delgado. FRELIMO militants were able to evade pursuit and surveillance by employing classic guerrilla tactics: ambushing patrols, sabotaging communication and railroad lines, and making hit-and-run attacks against colonial outposts before rapidly fading into accessible backwater areas. The insurgents took full advantage of the

In 1964, attempts at peaceful negotiation by FRELIMO were abandoned and, on 25 September, Eduardo Mondlane began to launch guerrilla attacks on targets in northern Mozambique from his base in Tanzania. FRELIMO soldiers, with logistical assistance from the local population, attacked the administrative post at Chai in the province of Cabo Delgado. FRELIMO militants were able to evade pursuit and surveillance by employing classic guerrilla tactics: ambushing patrols, sabotaging communication and railroad lines, and making hit-and-run attacks against colonial outposts before rapidly fading into accessible backwater areas. The insurgents took full advantage of the

Due to both the technological gap between civilizations and the centuries-long colonial era, Portugal had been a driving force in the development of all of Portuguese Africa since the 15th century. In the 1960s and early 1970s, to counter the increasing insurgency of FRELIMO forces and show to the Portuguese people and the world that the territory was totally under control, the Portuguese government accelerated its major development program to expand and upgrade the infrastructure of Portuguese Mozambique by creating new roads, railways, bridges, dams, irrigation systems, schools and hospitals to stimulate an even higher level of economic growth and support from the populace.

Due to both the technological gap between civilizations and the centuries-long colonial era, Portugal had been a driving force in the development of all of Portuguese Africa since the 15th century. In the 1960s and early 1970s, to counter the increasing insurgency of FRELIMO forces and show to the Portuguese people and the world that the territory was totally under control, the Portuguese government accelerated its major development program to expand and upgrade the infrastructure of Portuguese Mozambique by creating new roads, railways, bridges, dams, irrigation systems, schools and hospitals to stimulate an even higher level of economic growth and support from the populace.

O Desenvolvimento de Moçaqmbique e a Promoção das Suas Populaçōes – Situaçāo em 1974, Kaúlza de Arriaga's published works and texts

As part of this redevelopment program, construction of the Cahora Bassa Dam began in 1969. This particular project became intrinsically linked with Portugal's concerns over security in the overseas territories. The Portuguese government viewed the construction of the dam as testimony to Portugal's "civilising mission" and intended for the dam to reaffirm Mozambican belief in the strength and security of the Portuguese overseas government. To this end, Portugal sent three thousand new troops and over one million landmines to Mozambique to defend the building project. Realizing the symbolic significance of the dam to the Portuguese, FRELIMO spent seven years attempting to halt its construction by force. No direct attacks were ever successful, but FRELIMO had some success in attacking convoys ''en route'' to the site. FRELIMO also lodged a protest with the United Nations about the project, and their cause was aided by negative reports of Portuguese actions in Mozambique. In spite of the subsequent withdrawal of much foreign financial support for the dam, it was finally completed in December 1974. The dam's intended propaganda value to the Portuguese was overshadowed by the adverse Mozambican public reaction to the extensive dispersal of the indigenous populace, who were forced to relocate from their homes to allow for the construction project. The dam also deprived farmers of the critical annual floods, which formerly re-fertilized the plantations.

On 3 February 1969, Mondlane was killed by explosives smuggled into his office in Dar es Salaam. Many sources state that, in an attempt to rectify the situation in Mozambique, the Portuguese secret police assassinated Mondlane by sending a parcel with a book containing an explosive device, which detonated upon opening. Other sources state that Eduardo was killed when an explosive device detonated underneath his chair at the FRELIMO headquarters, and that the faction responsible was never identified.

The original investigations levelled accusations at Silverio Nungo (who was later executed) and Lazaro Kavandame, FRELIMO leader in Cabo Delgado. The latter had made no secret of his distrust of Mondlane, seeing him as too conservative a leader, and the Tanzanian police also accused him of working with

On 3 February 1969, Mondlane was killed by explosives smuggled into his office in Dar es Salaam. Many sources state that, in an attempt to rectify the situation in Mozambique, the Portuguese secret police assassinated Mondlane by sending a parcel with a book containing an explosive device, which detonated upon opening. Other sources state that Eduardo was killed when an explosive device detonated underneath his chair at the FRELIMO headquarters, and that the faction responsible was never identified.

The original investigations levelled accusations at Silverio Nungo (who was later executed) and Lazaro Kavandame, FRELIMO leader in Cabo Delgado. The latter had made no secret of his distrust of Mondlane, seeing him as too conservative a leader, and the Tanzanian police also accused him of working with

During the entire period of 1970–74, FRELIMO intensified guerrilla operations, specializing in urban terrorism. The use of landmines also intensified, with sources stating that they had become responsible for two out of every three Portuguese casualties. During the conflict, FRELIMO used a variety of

During the entire period of 1970–74, FRELIMO intensified guerrilla operations, specializing in urban terrorism. The use of landmines also intensified, with sources stating that they had become responsible for two out of every three Portuguese casualties. During the conflict, FRELIMO used a variety of

Problems for the Portuguese arose almost immediately when the offensive coincided with the beginning of the monsoon season, creating additional logistical difficulties. Not only were the Portuguese soldiers badly equipped, but there was very poor cooperation, if any at all, between the FAP and the army. Thus, the army lacked close air support from the FAP. Mounting Portuguese casualties began to outweigh FRELIMO casualties, leading to further political intervention from Lisbon.

The Portuguese eventually reported 651 guerrillas as killed (a figure of some 440 was most likely closer to reality) and 1,840 captured, for the loss of 132 Portuguese soldiers. Arriaga also claimed his troops destroyed 61 guerrilla bases and 165 guerrilla camps, while 40 tons of ammunition had been captured in the first two months. Although "Gordian Knot" was the most effective Portuguese offensive of the conflict, weakening guerrillas to such a degree that they were no longer a significant threat, the operation was deemed a failure by some military officers and the government.

On 16 December 1972, the Portuguese 6th company of Commandos in Mozambique killed the inhabitants of the village of Wiriyamu, in the district of Tete. Referred to as the ' Wiriyamu Massacre', the soldiers killed between 150 (according to the Red Cross) and 300 (according to a much later investigation by the Portuguese newspaper '' Expresso'' based in testimonies from soldiers) villagers accused of sheltering FRELIMO guerrillas. The action, "Operation Marosca", was planned at the instigation of PIDE agents and guided by agent Chico Kachavi, who was later assassinated while an inquiry into the events was being carried out. The soldiers were told by this agent that "the orders were to kill them all", never mind that only civilians, women and children included, were found. All of the victims were civilians. The massacre was recounted in July 1973 by the British Catholic priest, Father

Problems for the Portuguese arose almost immediately when the offensive coincided with the beginning of the monsoon season, creating additional logistical difficulties. Not only were the Portuguese soldiers badly equipped, but there was very poor cooperation, if any at all, between the FAP and the army. Thus, the army lacked close air support from the FAP. Mounting Portuguese casualties began to outweigh FRELIMO casualties, leading to further political intervention from Lisbon.

The Portuguese eventually reported 651 guerrillas as killed (a figure of some 440 was most likely closer to reality) and 1,840 captured, for the loss of 132 Portuguese soldiers. Arriaga also claimed his troops destroyed 61 guerrilla bases and 165 guerrilla camps, while 40 tons of ammunition had been captured in the first two months. Although "Gordian Knot" was the most effective Portuguese offensive of the conflict, weakening guerrillas to such a degree that they were no longer a significant threat, the operation was deemed a failure by some military officers and the government.

On 16 December 1972, the Portuguese 6th company of Commandos in Mozambique killed the inhabitants of the village of Wiriyamu, in the district of Tete. Referred to as the ' Wiriyamu Massacre', the soldiers killed between 150 (according to the Red Cross) and 300 (according to a much later investigation by the Portuguese newspaper '' Expresso'' based in testimonies from soldiers) villagers accused of sheltering FRELIMO guerrillas. The action, "Operation Marosca", was planned at the instigation of PIDE agents and guided by agent Chico Kachavi, who was later assassinated while an inquiry into the events was being carried out. The soldiers were told by this agent that "the orders were to kill them all", never mind that only civilians, women and children included, were found. All of the victims were civilians. The massacre was recounted in July 1973 by the British Catholic priest, Father  By 1973, FRELIMO were also mining civilian towns and villages in an attempt to undermine the civilian confidence in the Portuguese forces. "Aldeamentos: agua para todos" (Resettlement villages: water for everyone) was a commonly seen message in the rural areas, as the Portuguese sought to relocate and resettle the indigenous population, in order to isolate the FRELIMO from its civilian base. Conversely, Mondlane's policy of mercy towards civilian Portuguese settlers was abandoned in 1973 by the new commander, Machel. "Panic, demoralisation, abandonment, and a sense of futility—all were reactions among whites in Mozambique" stated conflict historian T.H. Henricksen in 1983. This change in tactics led to protests by Portuguese settlers against the Lisbon government, a telltale sign of the conflict's unpopularity. Combined with the news of the Wiriyamu Massacre and that of renewed FRELIMO onslaughts through 1973 and early 1974, the worsening situation in Mozambique later contributed to the downfall of the Portuguese government in 1974. A Portuguese journalist argued:

By 1973, FRELIMO were also mining civilian towns and villages in an attempt to undermine the civilian confidence in the Portuguese forces. "Aldeamentos: agua para todos" (Resettlement villages: water for everyone) was a commonly seen message in the rural areas, as the Portuguese sought to relocate and resettle the indigenous population, in order to isolate the FRELIMO from its civilian base. Conversely, Mondlane's policy of mercy towards civilian Portuguese settlers was abandoned in 1973 by the new commander, Machel. "Panic, demoralisation, abandonment, and a sense of futility—all were reactions among whites in Mozambique" stated conflict historian T.H. Henricksen in 1983. This change in tactics led to protests by Portuguese settlers against the Lisbon government, a telltale sign of the conflict's unpopularity. Combined with the news of the Wiriyamu Massacre and that of renewed FRELIMO onslaughts through 1973 and early 1974, the worsening situation in Mozambique later contributed to the downfall of the Portuguese government in 1974. A Portuguese journalist argued:

Fighting colonial wars in Portuguese colonies had absorbed forty-four percent of the overall Portuguese budget, which led to a diversion of funds from infrastructure developments in Portugal, contributing to the growing unrest. The unpopularity of the Colonial Wars among many Portuguese led to the formation of magazines and newspapers, such as ''Cadernos Circunstância'', ''Cadernos Necessários'', ''Tempo e Modo'', and ''Polémica'', which had support from students and called for political solutions to Portugal's colonial problems. Dissatisfaction in Portugal culminated on 25 April 1974, when the Carnation Revolution, a peaceful leftist military ''coup d'état'' in Lisbon, ousted the incumbent Portuguese government of

Fighting colonial wars in Portuguese colonies had absorbed forty-four percent of the overall Portuguese budget, which led to a diversion of funds from infrastructure developments in Portugal, contributing to the growing unrest. The unpopularity of the Colonial Wars among many Portuguese led to the formation of magazines and newspapers, such as ''Cadernos Circunstância'', ''Cadernos Necessários'', ''Tempo e Modo'', and ''Polémica'', which had support from students and called for political solutions to Portugal's colonial problems. Dissatisfaction in Portugal culminated on 25 April 1974, when the Carnation Revolution, a peaceful leftist military ''coup d'état'' in Lisbon, ousted the incumbent Portuguese government of

''The Soviet Offensive in Southern Africa''

'' Air University Review''. Retrieved on 10 March 2007 * * Cooper, Tom. , ACIG, 2 September 2003. Retrieved on 7 March 2007

''Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane (1920–1969)''

''Frelimo''

Britannica.com. Retrieved on 12 October 2006 * Retrieved on 10 March 2007 * Newitt, Malyn

''Mozambique''

2009-11-01),

''Trends in Soviet Support for African Liberation''

'' Air University Review''. Retrieved on 10 March 2007 * Westfall, William C. Jr. (1 April 1984)

''Mozambique-Insurgency Against Portugal, 1963–1975''.

Retrieved on 15 February 2007 * Wright, Robin (12 May 1975)

Retrieved on 10 March 2007

Guerra Colonial: 1961–1974 – State-supported historical site of the Portuguese Colonial War (Portugal)

The official FRELIMO site (Mozambique)

* ''Time'' magazine

{{Authority control Communism in Mozambique Separatism in Mozambique Separatism in Portugal Military history of Mozambique Wars involving Portugal Wars involving Libya Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa *Mozambican African resistance to colonialism Military history of the Indian Ocean

armed conflict

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

between the guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

forces of the Mozambique Liberation Front

FRELIMO (; from , ) is a democratic socialist political party in Mozambique. It has governed the country since its independence from Portugal in 1975.

Founded in 1962, FRELIMO began as a nationalist movement fighting for the self-determination ...

(FRELIMO) and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

. The war officially started on 25 September 1964, and ended with a ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce), also spelled cease-fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions often due to mediation by a third party. Ceasefires may b ...

on 8 September 1974, resulting in a negotiated independence in 1975.

Portugal's wars against guerrilla fighters seeking independence in its 400-year-old African territories began in 1961 with Angola. In Mozambique, the conflict erupted in 1964 as a result of unrest and frustration amongst many indigenous Mozambican populations, who perceived foreign rule as exploitation and mistreatment, which served only to further Portuguese economic interests in the region. Many Mozambicans also resented Portugal's policies towards indigenous people, which resulted in discrimination and limited access to Portuguese-style education and skilled employment.

As successful self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

movements spread throughout Africa after World War II, many Mozambicans became progressively more nationalistic in outlook, and increasingly frustrated by the nation's continued subservience to foreign rule. For the other side, many enculturate

Enculturation is the process by which people learn the dynamics of their surrounding culture and acquire values and norms appropriate or necessary to that culture and its worldviews.

Definition and history of research

The term enculturation ...

d indigenous Africans who were fully integrated into the social organization of Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique () or Portuguese East Africa () were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese Empire, Portuguese overseas province. Portuguese Mozambique originally constituted a str ...

, in particular those from urban centres, reacted to claims of independence with a mixture of discomfort and suspicion. The ethnic Portuguese of the territory, which included most of the ruling authorities, responded with increased military presence and fast-paced development projects.

A mass exile of Mozambique's political intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

to neighboring countries provided havens from which radical Mozambicans could plan actions and foment political unrest in their homeland. The formation of FRELIMO and the support of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, Gaddafi Government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

in Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

and Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

through arms and advisers, led to the outbreak of violence that was to last well over a decade.

From a military standpoint, the Portuguese regular army held the upper hand during the conflict against FRELIMO guerrilla forces. Nonetheless, Mozambique succeeded in achieving independence on 25 June 1975, after a civil resistance movement known as the Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution (), code-named Operation Historic Turn (), also known as the 25 April (), was a military coup by military officers that overthrew the Estado Novo government on 25 April 1974 in Portugal. The coup produced major socia ...

backed by portions of the military in Portugal overthrew the Salazar regime, thus ending 470 years of Portuguese colonial rule in the East African region. According to historians of the Revolution, the military coup in Portugal was in part fueled by protests concerning the conduct of Portuguese troops in their treatment of some of the indigenous Mozambican populace.George Wright, ''The Destruction of a Nation'', 1996Phil Mailer, ''Portugal – The Impossible Revolution?'', 1977 The growing communist influence within the group of Portuguese insurgents who led the military coup and the pressure of the international community in relation to the Portuguese Colonial War

The Portuguese Colonial War (), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War () or in the Portuguese Empire, former colonies as the War of Liberation (), and also known as the Angolan War of Independence, Angolan, Guinea-Bissau War of Independence ...

were the primary causes of the outcome.Stewart Lloyd-Jones, ISCTE (Lisbon)Portugal's history since 1974

"The Portuguese Communist Party (PCP–Partido Comunista Português), which had courted and infiltrated the MFA from the very first days of the revolution, decided that the time was now right for it to seize the initiative. Much of the radical fervour that was unleashed following Spínola's coup attempt was encouraged by the PCP as part of their own agenda to infiltrate the MFA and steer the revolution in their direction.", Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril,

University of Coimbra

The University of Coimbra (UC; , ) is a Public university, public research university in Coimbra, Portugal. First established in Lisbon in 1290, it went through a number of relocations until moving permanently to Coimbra in 1537. The university ...

Background

Portuguese colonial rule

San hunter and gatherers, ancestors of the Khoisani peoples, were the first known inhabitants of the region that is now Mozambique, followed in the 1st and 4th centuries by Bantu-speaking peoples who migrated there across theZambezi River

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than half of t ...

. In 1498, Portuguese explorers landed on the Mozambican coastline.Kennedy, ThomasMozambique

''The Catholic Encyclopaedia''. Retrieved on 10 March 2007 Portugal's influence in East Africa grew throughout the 16th century; it established several colonies known collectively as Portuguese East Africa. Slavery and gold became profitable for the Europeans; influence was largely exercised through individual settlers and there was no centralized administration.T. H. Henriksen, ''Remarks on Mozambique'', 1975, p. 11

Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

in South America, the Portuguese began to focus on expanding their African colonies. This brought them into direct conflict with the British. Since David Livingstone had returned to the area in 1858 in an attempt to foster trade routes, British interest in Mozambique had risen, alarming the Portuguese government. During the 19th century, much of Eastern Africa was still being brought under British control, and in order to facilitate this, the British government required several concessions from the Portuguese colony.

Malyn D. D. NewittMozambique

, Encarta. Retrieved on 10 March 2007

Archived

1 November 2009. As a result, in an attempt to avoid a naval conflict with the superior

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, Portugal adjusted the borders of its colony and the modern borders of Mozambique were established in May 1881. Control of Mozambique was left to various organizations such as the Mozambique Company, the Zambezi Company and the Niassa Company which were financed by British investors and provided with cheap labour by immigrants from British East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was a British protectorate in the African Great Lakes, occupying roughly the same area as present-day Kenya, from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Cont ...

to work mines and construct railways.

The Gaza Empire

The Gaza Empire (1824–1895) was an African empire established by Soshangane and was located in southeastern Africa in the area of southern Mozambique and southeastern Zimbabwe. The Gaza Empire, at its height in the 1860s, covered all of M ...

, a collection of indigenous tribes who inhabited the area that now constitutes Mozambique and Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

, was defeated by the Portuguese in 1895, and the remaining inland tribes were eventually defeated by 1902; in that same year, Portugal established Lourenço Marques

Maputo () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Mozambique. Located near the southern end of the country, it is within of the borders with Eswatini and South Africa. The city has a population of 1,088,449 (as of 2017) distributed ov ...

as the capital.Malyn Newitt, ''A History of Mozambique'', 1995 p. 382 In 1926, political and economic crisis in Portugal led to the establishment of the Second Republic (later to become the Estado Novo), and a revival of interest in the African colonies. Calls for self determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

in Mozambique arose shortly after World War II, in light of the independence granted to many other colonies worldwide in the great wave of decolonisation

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

.

Rise of FRELIMO

Portugal designated Mozambique anoverseas territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

in 1951 in order to show the world that the colony had greater autonomy. It was called the Overseas Province of Mozambique (''Província Ultramarina de Moçambique''). Nonetheless, Portugal still maintained strong control over its colony. The increasing number of newly independent African nations after World War II, coupled with the ongoing mistreatment of the indigenous population, encouraged the growth of nationalist sentiment within Mozambique.

Mozambique was marked by large disparities between the wealthy Portuguese and the rural indigenous African population. Poorer whites, including illiterate peasants, were given preference in lower-level urban jobs, where a system of job reservation existed.Allen and Barbara Isaacman, ''Mozambique – From Colonialism to Revolution'', Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1983, p. 58 In the rural areas, Portuguese controlled the trading stores with which African peasants interacted.M. Bowen, ''The State Against the Peasantry: Rural Struggles in Colonial and Postcolonial Mozambique'' University Press of Virginia: Charlottesville, 2000 Being largely illiterate

Literacy is the ability to read and write, while illiteracy refers to an inability to read and write. Some researchers suggest that the study of "literacy" as a concept can be divided into two periods: the period before 1950, when literacy was ...

and preserving their local traditions and ways of life, skilled employment opportunities and roles in administration and government were rare for these numerous tribal

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

populations, leaving them few or no opportunities in the urban modern life. Many indigenous peoples saw their culture and tradition being overwhelmed by the alien culture of Portugal. A small educated African class did emerge, but faced substantial discrimination.J.M. Penvenne, Joao Dos Santos Albasini (1876–1922): The Contradictions of Politics and Identity in Colonial Mozambique, ''Journal of African History'', 1996, No. 37

Vocal political dissidents opposed to Portuguese rule and claiming independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

were typically forced into exile. From the mid-1920s onward, unions and left-wing opposition groups were suppressed within both Portugal and its colonies by the authoritarian Estado Novo regime.

The Portuguese government forced black Mozambican farmers to grow rice or cotton for export, providing little for the farmers to support themselves. Many other workers—over 250,000 by 1960—were pressured to work on coal and gold mines in neighboring territories, mainly in South Africa, where they comprised over 30% of black underground miners.Malyn Newitt, A History of Mozambique, 1995 p. 517

By 1950, only 4,353 Mozambicans out of 5,733,000 had been granted the right to vote by the Portuguese colonial government. The rift between Portuguese settlers and Mozambican locals is illustrated in one way by the small number of people with mixed Portuguese and Mozambican heritage (''mestiço''), numbering only 31,465 in a population of 8–10 million in 1960 according to that year's census.

The Mozambique Liberation Front

FRELIMO (; from , ) is a democratic socialist political party in Mozambique. It has governed the country since its independence from Portugal in 1975.

Founded in 1962, FRELIMO began as a nationalist movement fighting for the self-determination ...

, or FRELIMO, formally Marxist-Leninist as of 1977 but adherent to such positions since the late 1960s,B. Munslow, editor, ''Samora Machel, an African Revolutionary: Selected Speeches and Writings'', London: Zed Books, 1985 was formed in Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (, ; from ) is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over 7 million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa by population and the ...

, Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, on 25 June 1962, under the leadership of sociologist Eduardo Mondlane

Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane (20 June 1920 – 3 February 1969) was a Mozambican revolutionary and anthropologist who was the founder of the Mozambican Liberation Front (FRELIMO). He served as the FRELIMO's first leader until his assassinat ...

. It was created during a conference of political figures who had been forced into exile,Malyn Newitt, ''A History of Mozambique'', 1995, p. 541 by the merging of various existing nationalist groups, including the Mozambican African National Union, National African Union of Independent Mozambique and the National Democratic Union of Mozambique which had been formed two years earlier. It was only in exile that such political movements could develop, due to the strength of Portugal's grip on dissident activity within Mozambique itself.

The United Nations also put pressure on Portugal to move for decolonization. Portugal threatened to withdraw from NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

, which put a stop to pressure from within the NATO bloc, and nationalist groups in Mozambique were forced to turn to Soviet bloc for aid.

International consciousness and support

Leaders of the Mozambican independence movement were educated abroad and thus brought a focus on the transnational to their liberation efforts.Marcelino dos Santos

Marcelino dos Santos (20 May 1929 – 11 February 2020) was a Mozambique, Mozambican poet, revolutionary, and politician. As a young man he travelled to Portugal, and France for an education. He was a founding member of the FRELIMO, ''Frente de ...

, the movement's unofficial diplomat, took the lead on international networking between the movement and other countries that provided aid. They read Mao's works and thus adopted Maoist

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic o ...

and Marxist–Leninist ideology at an early stage, even though the group's Marxist–Leninist affiliations were not made official until 1977. As such, their approach to the war for independence was rooted in understanding of international liberation struggles, especially those by countries that would later align themselves with Marx-Leninism or communism. FRELIMO's fighting strategy was inspired by anti-colonial wars and other guerrilla campaigns in China, South Vietnam and Algeria.

FRELIMO was recognized early on by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), a group founded by Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

and other African leaders, focused on eradicating colonialism and neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

from the African continent. The OAU provided funds in support of the independence fight.

Such support from other free nations on the African continent was crucial to the war effort. FRELIMO, and other Mozambican liberation groups that preceded it, were based in Tanzania because the character of Portuguese colonization under the Estado Novo was so repressive that it was nearly impossible for such resistance movements to begin and flourish in Mozambique proper. When Tanzania gained independence in 1961, President Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian politician, anti-colonial activist, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika (1961–1964), Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as presid ...

permitted liberation movements in exile, including FRELIMO, to have the country as their base of operations. On the African continent, FRELIMO received support from Tanzania, Algeria, and Egypt, among other independent nations.

In the spring of 1972, Romania allowed FRELIMO to open a diplomatic mission in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

, the first of its kind in Eastern Europe. In 1973, Nicolae Ceaușescu

Nicolae Ceaușescu ( ; ; – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian politician who was the second and last Communism, communist leader of Socialist Romania, Romania, serving as the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 u ...

recognized FRELIMO as "the only legitimate representative of the Mozambican people", an important precedent. Machel stressed that—during his trip to the Soviet Union—he and his delegation were granted "the status that we are entitled to" due to Romania's official recognition of FRELIMO. In terms of material support, Romanian trucks were used to transport weapons and ammunition to the front, as well as medicine, school material and agricultural equipment. Romanian tractors contributed to the increase in agricultural production. Romanian weapons and uniforms—reportedly of "excellent quality"—played a "decisive role" in FRELIMO's military progress. It was in early 1973 that FRELIMO made these statements about Romania's material support, in a memorandum sent to the Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ; PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave an ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that would replace the social system ...

's Central Committee.

During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, and particularly in the late 1950s, the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China adopted a strategy of destabilization of Western powers by disrupting their hold on African colonies. Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, in particular, viewed the 'underdeveloped third of mankind' as a means to weaken the West. For the Soviets, Africa represented a chance to create a rift between western powers and their colonial assets, and create pro-communist states in Africa with which to foster future relations.Valentine J. Belfiglio. The Soviet Offensive in South Africa

'', airpower.maxwell, af.mil, 1983. Retrieved on 10 March 2007 Prior to the formation of FRELIMO, the Soviet position regarding the nationalist movements in Mozambique was confused. There were multiple independence movements, and they had no sure knowledge that any would succeed. The liberation movement's largely Marxist–Leninist principles and the eastern bloc's strategy of destabilization made Mozambican alliance with other left nations of the world seem like a foregone conclusion. Nationalist groups in Mozambique, like those across Africa during the period, received training and equipment from the Soviet Union. But leaders of the movement for independence also wanted to balance their support. As such, they lobbied for and received support from both eastern bloc and non-aligned nations upon its consolidation into FRELIMO. The movement was even initially supported by the U.S. government. In 1963, Mondlane met with Kennedy administration officials who later provided a $60,000 CIA subsidy in support of the movement. The Kennedy administration, however, rejected his request for military aid and by 1968 the Johnson administration severed all financial ties. Eduardo Mondlane's successor, future President of Mozambique,

Samora Machel

Samora Moisés Machel (29 September 1933 – 19 October 1986) was a Mozambique, Mozambican politician and revolutionary. A Socialism, socialist in the tradition of Marxism–Leninism, he served as the first President of Mozambique from the coun ...

, acknowledged assistance from both Moscow and Peking, describing them as "the only ones who will really help us. They have fought armed struggles, and whatever they have learned that is relevant to Mozambique we will use." Guerrillas received training in subversion and political warfare as well as military aid, specifically shipments of 122mm artillery rockets in 1972, with 1,600 advisors from Russia, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

and East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

.''U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to the Congress'' 1972 Chinese military instructors also trained soldiers in Tanzania.

Cuba's relationship with the Mozambican liberation movement was somewhat more fraught than that which FRELIMO fostered with the Soviet Union and China. Cuba had a similar interest in African wars for liberation as a potential locus for the spread of the ideology of the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution () was the military and political movement that overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled Cuba from 1952 to 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, in which Batista overthrew ...

. The Cubans identified Mozambique's war for liberation as one of the most important ones occurring in Africa at the time. But Cuba's efforts to make connection with FRELIMO were frustrated almost from the outset. In 1965, Mondlane met with Argentine marxist revolutionary Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

in Dar es Salaam to discuss potential collaboration. The meeting ended acrimoniously when Guevara called into question the reports of FRELIMO's prowess, which it had greatly exaggerated in the press. Cubans also tried to convince FRELIMO to agree to train their guerrillas in Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

, which Mondlane refused. Eventually, these initial disagreements were resolved and Cubans agreed to train FRELIMO guerrillas in Cuba and continued to provide weapons, food, and uniforms for the movement. Cuba also acted as a conduit for communication between Mozambique and its fellow Portuguese colony Angola, and Latin American nations in the thrall of their own revolutionary movements such as Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala.

European nations that provided FRELIMO with military and/or humanitarian support were Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands. FRELIMO also had a small but significant network of support based in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

The United States was non-involved in the conflict.

Conflict

Insurgency under Mondlane (1964–69)

At the war's outset, FRELIMO had little hope for a conventional military victory, with a mere 7,000 combatants against a far larger Portuguese force. Their hopes rested on urging the local populace to support the insurgency, in order to force a negotiated independence from Lisbon. Portugal fought its own version of protracted warfare, and a large military force was sent to quell the unrest, with troop numbers rising from 8,000 to 24,000 between 1964 and 1967.

The military wing of FRELIMO was commanded by Filipe Samuel Magaia, whose forces received training from

At the war's outset, FRELIMO had little hope for a conventional military victory, with a mere 7,000 combatants against a far larger Portuguese force. Their hopes rested on urging the local populace to support the insurgency, in order to force a negotiated independence from Lisbon. Portugal fought its own version of protracted warfare, and a large military force was sent to quell the unrest, with troop numbers rising from 8,000 to 24,000 between 1964 and 1967.

The military wing of FRELIMO was commanded by Filipe Samuel Magaia, whose forces received training from Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

. The FRELIMO guerrillas were armed with a variety of weapons, many provided by the Soviet Union and China. Common weapons included the Mosin–Nagant

The Mosin–Nagant is a five-shot, Bolt action, bolt-action, Magazine (firearms), internal magazine–fed military rifle. Known officially as the 3-line rifle M1891, in Russia and the former Soviet Union as Mosin's rifle (, ISO 9: ) and inform ...

bolt-action rifle, SKS and AK-47

The AK-47, officially known as the Avtomat Kalashnikova (; also known as the Kalashnikov or just AK), is an assault rifle that is chambered for the 7.62×39mm cartridge. Developed in the Soviet Union by Russian small-arms designer Mikhail Kala ...

automatic rifles and the Soviet PPSh-41

The PPSh-41 () is a selective-fire, open-bolt, blowback submachine gun that fires the 7.62×25mm Tokarev round. It was designed by Georgy Shpagin of the Soviet Union to be a cheaper and simplified alternative to the PPD-40.

The PPSh-41 saw ...

. Machine guns such as the Degtyarev light machine gun were widely used, along with the DShK

The DShK M1938 (Cyrillic: ДШК, for ) is a Soviet heavy machine gun. The weapon may be vehicle mounted or used on a tripod or wheeled carriage as a heavy infantry machine gun. The DShK's name is derived from its original designer, Vasily Degtya ...

and the SG-43 Gorunov. FRELIMO were supported by mortars, recoilless rifle

A Recoilless rifle (rifled), recoilless launcher (smoothbore), or simply recoilless gun, sometimes abbreviated to "rr" or "RCL" (for ReCoilLess) is a type of lightweight artillery system or man-portable launcher that is designed to eject some fo ...

s, RPG-2

The RPG-2 ( Russian: РПГ-2, Ручной противотанковый гранатомёт, ''Ruchnoy Protivotankovy Granatomyot''; English: "hand-held antitank grenade launcher") is a man-portable, shoulder-fired anti-tank weapon that was de ...

s and RPG-7

The RPG-7 is a portable, reusable, unguided, shoulder-launched, anti-tank, rocket launcher. The RPG-7 and its predecessor, the RPG-2, were designed by the Soviet Union, and are now manufactured by the Russian company Bazalt. The weapon has t ...

s, Anti-aircraft weapons

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface ( submarine-launched), and air-ba ...

such as the ZPU-4. In the dying stages of the conflict, FRELIMO was provided with a few SA-7

The 9K32 Strela-2 (; NATO reporting name SA-7 Grail) is a light-weight, shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missile or MANPADS system. It is designed to target aircraft at low altitudes with passive infrared-homing guidance and destroy them with a ...

MANPAD

Man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS or MPADS) are portable shoulder-launched surface-to-air missiles. They are guided weapons and are a threat to low-flying aircraft, especially helicopters and also used against low-flying cruise missi ...

shoulder-launched missile launchers from China; these were never used to shoot down any Portuguese aircraft. Only one Portuguese aircraft was lost in combat during the conflict, when Lt. Emilio Lourenço's G.91R-4 was destroyed by premature detonation of his own ordnance.

The Portuguese forces were under the command of General António Augusto dos Santos, a man with strong faith in new counter-insurgency theories. Augusto dos Santos supported a collaboration with Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

to create African Scout units and other special forces teams, with Rhodesian forces even conducting their own independent operations during the conflict. Due to Portuguese policy of retaining up-to-date equipment for the metropole

A metropole () is the homeland, central territory or the state exercising power over a colonial empire.

From the 19th century, the English term ''metropole'' was mainly used in the scope of the British, Spanish, French, Dutch, Portugu ...

while shipping obsolete equipment to their overseas territories, the Portuguese soldiers fighting in the opening stages of the conflict were equipped with World War II radios and the old Mauser rifle. As the fighting progressed, the need for more modern equipment was rapidly recognised, and the Heckler & Koch G3

The Heckler & Koch G3 () is a selective fire, select-fire battle rifle chambered in 7.62×51mm NATO developed in the 1950s by the German firearms manufacturer Heckler & Koch, in collaboration with the Spanish state-owned firearms manufacturer CE ...

and FN FAL

The FAL (, English: Light Automatic Rifle) is a battle rifle designed in Belgium by Dieudonné Saive and manufactured by FN Herstal and others since 1953.

During the Cold War the FAL was adopted by many countries of the NATO, North Atlantic Trea ...

rifles were adopted as the standard battlefield weapon, along with the AR-10

The ArmaLite AR-10 is a 7.62×51mm NATO battle rifle designed by Eugene Stoner in the late 1950s and manufactured by ArmaLite (then a division of the Fairchild (aircraft manufacturer), Fairchild Aircraft Corporation). When first introduced in 1956 ...

for paratroopers. The MG42 and, then in 1968, the HK21 were the Portuguese general purpose machine guns, with 60, 81 and 120mm mortars, howitzers and the AML-60, Panhard EBR

The Panhard EBR (Panhard ''Engin Blindé de Reconnaissance'', French: Armored Reconnaissance Vehicle) is an armoured car designed by Panhard for the French Army and later used across the globe, notably by the French Army during the Algerian War ...

, Fox and Chaimite armoured cars frequently deployed for fire support.

Start of FRELIMO attacks

In 1964, attempts at peaceful negotiation by FRELIMO were abandoned and, on 25 September, Eduardo Mondlane began to launch guerrilla attacks on targets in northern Mozambique from his base in Tanzania. FRELIMO soldiers, with logistical assistance from the local population, attacked the administrative post at Chai in the province of Cabo Delgado. FRELIMO militants were able to evade pursuit and surveillance by employing classic guerrilla tactics: ambushing patrols, sabotaging communication and railroad lines, and making hit-and-run attacks against colonial outposts before rapidly fading into accessible backwater areas. The insurgents took full advantage of the

In 1964, attempts at peaceful negotiation by FRELIMO were abandoned and, on 25 September, Eduardo Mondlane began to launch guerrilla attacks on targets in northern Mozambique from his base in Tanzania. FRELIMO soldiers, with logistical assistance from the local population, attacked the administrative post at Chai in the province of Cabo Delgado. FRELIMO militants were able to evade pursuit and surveillance by employing classic guerrilla tactics: ambushing patrols, sabotaging communication and railroad lines, and making hit-and-run attacks against colonial outposts before rapidly fading into accessible backwater areas. The insurgents took full advantage of the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

season in order to evade pursuit. During heavy rains, it was much more difficult to track insurgents by air, negating Portugal's air superiority, and Portuguese troops and vehicles found movement during rain storms difficult. In contrast, the insurgent troops, with lighter equipment, were able to flee into the bush (the ''mato'') amongst an ethnically similar populace into which they could melt away. Furthermore, the FRELIMO forces were able to forage food from the surroundings and local villages, and were thus not hampered by long supply lines.

With the initial FRELIMO attacks in Chai Chai, the fighting spread to Niassa

Niassa is a province of Mozambique with an area of 129,056 km2 and a population of 1,810,794 (2017). It is the most sparsely populated province in the country. Lichinga is the capital of the province. There are a minimum estimated 450,000 ...

and Tete

Tete may refer to:

* Tete, Mozambique, a city in Mozambique

*Tété (born 1975), a French musician

*Tetê (born 2000), a Brazilian footballer

*Tete Montoliu (1933–1997), Spanish jazz pianist

**''Tete!'', an album by Tete Montoliu

*Tete Province ...

at the center of Mozambique. During the early stages of the conflict, FRELIMO activity was reduced to small, platoon-sized engagements, harassments and raids on Portuguese installations. The FRELIMO forces often operated in small groups of ten to fifteen guerrillas. The scattered nature of FRELIMO's initial attacks was an attempt to disperse the Portuguese forces.

The Portuguese troops began to suffer losses in November, fighting in the northern region of Xilama. With increasing support from the populace, and the low number of Portuguese regular troops, FRELIMO was quickly able to advance south towards Meponda and Mandimba, linking to Tete with the aid of forces from the neighboring Republic of Malawi, which had become a fully independent member of the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

on 6 July 1964. Despite the increasing range of FRELIMO operations, attacks were still limited to small strike teams attacking lightly defended administrative outposts, with the FRELIMO lines of communication and supply utilizing canoes along the Ruvuma River and Lake Malawi

Lake Malawi, also known as Lake Nyasa in Tanzania and Lago Niassa in Mozambique, () is an African Great Lakes, African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the East African Rift system, located between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

It is ...

.

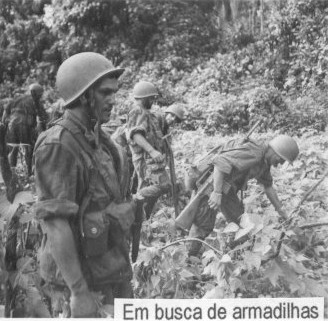

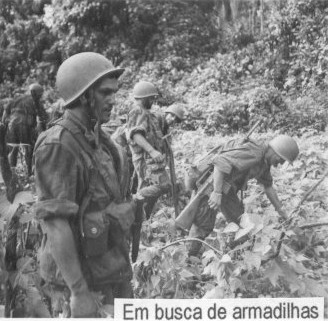

It was not until 1965 that recruitment of fighters increased along with popular support, and the strike teams were able to increase in size. The increase in popular support was in part due to FRELIMO's offer of help to exiled Mozambicans, who had fled the conflict by travelling to nearby Tanzania. Like similar conflicts against the French and United States forces in Vietnam, the insurgents also used landmines to a great extent to injure the Portuguese forces, thus straining the armed forces' infrastructureThomas H. Henriksen, ''Revolution and Counterrevolution'', London: Greenwood Press, 1983, p. 44 and demoralizing soldiers.

FRELIMO attack groups had also begun to grow in size to include over 100 soldiers in certain cases, and the insurgents also began to accept women fighters into their ranks. On either 10 October or 11 October 1966, on returning to Tanzania after inspecting the front lines, Filipe Samuel Magaia was shot dead by Lourenço Matola, a fellow FRELIMO guerrilla who was said to be in the employ of the Portuguese.

One seventh of the population and one fifth of the territory were in FRELIMO hands by 1967; at this time there were approximately 8000 guerrillas in combat. During this period, Mondlane urged further expansion of the war effort, but also sought to retain the small strike groups. With the increasing cost of supply, more and more territory liberated from the Portuguese, and the adoption of measures to win the support of the population, it was at this time that Mondlane sought assistance from abroad, specifically the Soviet Union and China; from these benefactors, he obtained large-calibre machine guns, anti-aircraft rifles and 75 mm recoilless rifles and 122 mm rockets. In 1967 East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

agreed to begin supplying FRELIMO with military aid. It equipped the organization with various stocks of arms—many of which were weapons of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

vintage—almost every year through the end of the war.

In 1968, the second Congress of FRELIMO was a propaganda victory for the insurgents, despite attempts by the Portuguese, who enjoyed air superiority throughout the conflict, to bomb the location of the meeting late in the day. This gave FRELIMO further weight to wield in the United Nations.

Portuguese development program

Due to both the technological gap between civilizations and the centuries-long colonial era, Portugal had been a driving force in the development of all of Portuguese Africa since the 15th century. In the 1960s and early 1970s, to counter the increasing insurgency of FRELIMO forces and show to the Portuguese people and the world that the territory was totally under control, the Portuguese government accelerated its major development program to expand and upgrade the infrastructure of Portuguese Mozambique by creating new roads, railways, bridges, dams, irrigation systems, schools and hospitals to stimulate an even higher level of economic growth and support from the populace.

Due to both the technological gap between civilizations and the centuries-long colonial era, Portugal had been a driving force in the development of all of Portuguese Africa since the 15th century. In the 1960s and early 1970s, to counter the increasing insurgency of FRELIMO forces and show to the Portuguese people and the world that the territory was totally under control, the Portuguese government accelerated its major development program to expand and upgrade the infrastructure of Portuguese Mozambique by creating new roads, railways, bridges, dams, irrigation systems, schools and hospitals to stimulate an even higher level of economic growth and support from the populace. Kaúlza de Arriaga

Kaúlza de Oliveira de Arriaga, OA, GCC, OC, OIH (18 January 1915 – 2 February 2004) was a Portuguese general, writer, professor and politician. He was Secretary of State (junior minister) of the Air Force between 1953 and 1955 and command ...

(General)O Desenvolvimento de Moçaqmbique e a Promoção das Suas Populaçōes – Situaçāo em 1974, Kaúlza de Arriaga's published works and texts

As part of this redevelopment program, construction of the Cahora Bassa Dam began in 1969. This particular project became intrinsically linked with Portugal's concerns over security in the overseas territories. The Portuguese government viewed the construction of the dam as testimony to Portugal's "civilising mission" and intended for the dam to reaffirm Mozambican belief in the strength and security of the Portuguese overseas government. To this end, Portugal sent three thousand new troops and over one million landmines to Mozambique to defend the building project. Realizing the symbolic significance of the dam to the Portuguese, FRELIMO spent seven years attempting to halt its construction by force. No direct attacks were ever successful, but FRELIMO had some success in attacking convoys ''en route'' to the site. FRELIMO also lodged a protest with the United Nations about the project, and their cause was aided by negative reports of Portuguese actions in Mozambique. In spite of the subsequent withdrawal of much foreign financial support for the dam, it was finally completed in December 1974. The dam's intended propaganda value to the Portuguese was overshadowed by the adverse Mozambican public reaction to the extensive dispersal of the indigenous populace, who were forced to relocate from their homes to allow for the construction project. The dam also deprived farmers of the critical annual floods, which formerly re-fertilized the plantations.

Assassination of Eduardo Mondlane

On 3 February 1969, Mondlane was killed by explosives smuggled into his office in Dar es Salaam. Many sources state that, in an attempt to rectify the situation in Mozambique, the Portuguese secret police assassinated Mondlane by sending a parcel with a book containing an explosive device, which detonated upon opening. Other sources state that Eduardo was killed when an explosive device detonated underneath his chair at the FRELIMO headquarters, and that the faction responsible was never identified.

The original investigations levelled accusations at Silverio Nungo (who was later executed) and Lazaro Kavandame, FRELIMO leader in Cabo Delgado. The latter had made no secret of his distrust of Mondlane, seeing him as too conservative a leader, and the Tanzanian police also accused him of working with

On 3 February 1969, Mondlane was killed by explosives smuggled into his office in Dar es Salaam. Many sources state that, in an attempt to rectify the situation in Mozambique, the Portuguese secret police assassinated Mondlane by sending a parcel with a book containing an explosive device, which detonated upon opening. Other sources state that Eduardo was killed when an explosive device detonated underneath his chair at the FRELIMO headquarters, and that the faction responsible was never identified.

The original investigations levelled accusations at Silverio Nungo (who was later executed) and Lazaro Kavandame, FRELIMO leader in Cabo Delgado. The latter had made no secret of his distrust of Mondlane, seeing him as too conservative a leader, and the Tanzanian police also accused him of working with PIDE

The International and State Defense Police (; PIDE) was a Portuguese security agency that existed during the '' Estado Novo'' regime of António de Oliveira Salazar. Formally, the main roles of the PIDE were the border, immigration and emigrati ...

(Portugal's secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

) to assassinate Mondlane. Kavandame himself surrendered to the Portuguese in April of that year.

Although the exact details of the assassination remain disputed, the involvement of the Portuguese government, particularly Aginter Press or PIDE, is generally accepted by most historians and biographers and is supported by the Portuguese stay behind Gladio-esque army, known as Aginter Press, that suggested in 1990 that they were responsible for the assassination. Initially, due to the uncertainty regarding who was responsible, Mondlane's death created great suspicion within the ranks of the FRELIMO itself and a short power struggle which resulted in a dramatic swing to the political left

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social hierarchies. Left-wing politi ...

.

Continuing war (1969–74)

In 1969, General António Augusto dos Santos was relieved of command, with GeneralKaúlza de Arriaga

Kaúlza de Oliveira de Arriaga, OA, GCC, OC, OIH (18 January 1915 – 2 February 2004) was a Portuguese general, writer, professor and politician. He was Secretary of State (junior minister) of the Air Force between 1953 and 1955 and command ...

taking over officially in March 1970. Kaúlza de Arriaga favored a more direct method of fighting the insurgents, and the established policy of using African counter-insurgency forces was rejected in favor of the deployment of regular Portuguese forces accompanied by a small number of African fighters. Indigenous personnel were still recruited for special operations, such as the Special Groups of Parachutists in 1973, though their role less significant under the new commander. His tactics were partially influenced by a meeting with United States General William Westmoreland

William Childs Westmoreland (26 March 1914 – 18 July 2005) was a United States Army general, most notably the commander of United States forces during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1968.

He served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army f ...

.

By 1972 there was growing pressure from other commanders, particularly Kaúlza de Arriaga's second in command, General Francisco da Costa Gomes

Francisco da Costa Gomes, Order of the Tower and Sword, ComTE Order of Aviz, GOA (; 30 June 1914 – 31 July 2001) was a former Portuguese people, Portuguese military officer and politician who was the 15th President of Portugal from 1974 to 19 ...

, for the use of African soldiers in '' Flechas'' units. Flechas units (''Arrows'') were also employed in Angola and were units under the command of the PIDE. Composed of local tribesmen, the units specialized in tracking, reconnaissance and anti-terrorist operations.

Costa Gomes argued that African soldiers were cheaper and were better able to create a relationship with the local populace, a tactic similar to the ' hearts and minds' strategy being used by United States forces in Vietnam at the time. These Flechas units saw action in the territory at the very end stages of the conflict, following the dismissal of Arriaga on the eve of the Portuguese coup in 1974. The units were to continue to cause problems for the FRELIMO even after the Revolution and Portuguese withdrawal, when the country splintered into civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

.

During the entire period of 1970–74, FRELIMO intensified guerrilla operations, specializing in urban terrorism. The use of landmines also intensified, with sources stating that they had become responsible for two out of every three Portuguese casualties. During the conflict, FRELIMO used a variety of

During the entire period of 1970–74, FRELIMO intensified guerrilla operations, specializing in urban terrorism. The use of landmines also intensified, with sources stating that they had become responsible for two out of every three Portuguese casualties. During the conflict, FRELIMO used a variety of anti-tank

Anti-tank warfare refers to the military strategies, tactics, and weapon systems designed to counter and destroy enemy armored vehicles, particularly tanks. It originated during World War I following the first deployment of tanks in 1916, and ...

and anti-personnel

An anti-personnel weapon is a weapon primarily used to maim or kill infantry and other personnel not behind armor, as opposed to attacking structures or vehicles, or hunting game. The development of defensive fortification and combat vehicles gav ...

mines, including the PMN (Black Widow), TM-46, and POMZ. Even amphibious mines were used, such as the PDM. Mine psychosis, an acute fear of landmines, was rampant in the Portuguese forces. This fear, coupled with the frustration of taking casualties without ever seeing the enemy forces, damaged morale and significantly hampered progress.

Portuguese counter-offensive (June 1970)

On 10 June 1970, a major counter-offensive was launched by the Portuguese army. Operation Gordian Knot (Portuguese: Operação Nó Górdio) targeted permanent insurgent camps and the infiltration routes across the Tanzanian border in the north of Mozambique over a period of seven months. The operation involved some 35,000 Portuguese troops, particularly elite units like paratroopers, commandos, marines and naval fusiliers.Tom Cooper., ACIG.org, 2 September 2003. Retrieved on 7 March 2007 Problems for the Portuguese arose almost immediately when the offensive coincided with the beginning of the monsoon season, creating additional logistical difficulties. Not only were the Portuguese soldiers badly equipped, but there was very poor cooperation, if any at all, between the FAP and the army. Thus, the army lacked close air support from the FAP. Mounting Portuguese casualties began to outweigh FRELIMO casualties, leading to further political intervention from Lisbon.

The Portuguese eventually reported 651 guerrillas as killed (a figure of some 440 was most likely closer to reality) and 1,840 captured, for the loss of 132 Portuguese soldiers. Arriaga also claimed his troops destroyed 61 guerrilla bases and 165 guerrilla camps, while 40 tons of ammunition had been captured in the first two months. Although "Gordian Knot" was the most effective Portuguese offensive of the conflict, weakening guerrillas to such a degree that they were no longer a significant threat, the operation was deemed a failure by some military officers and the government.

On 16 December 1972, the Portuguese 6th company of Commandos in Mozambique killed the inhabitants of the village of Wiriyamu, in the district of Tete. Referred to as the ' Wiriyamu Massacre', the soldiers killed between 150 (according to the Red Cross) and 300 (according to a much later investigation by the Portuguese newspaper '' Expresso'' based in testimonies from soldiers) villagers accused of sheltering FRELIMO guerrillas. The action, "Operation Marosca", was planned at the instigation of PIDE agents and guided by agent Chico Kachavi, who was later assassinated while an inquiry into the events was being carried out. The soldiers were told by this agent that "the orders were to kill them all", never mind that only civilians, women and children included, were found. All of the victims were civilians. The massacre was recounted in July 1973 by the British Catholic priest, Father