Mount Longhurst on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cook Mountains () is a group of

The Cook Mountains are bounded by the Darwin Glacier to the south, which separates the range from the

The Cook Mountains are bounded by the Darwin Glacier to the south, which separates the range from the

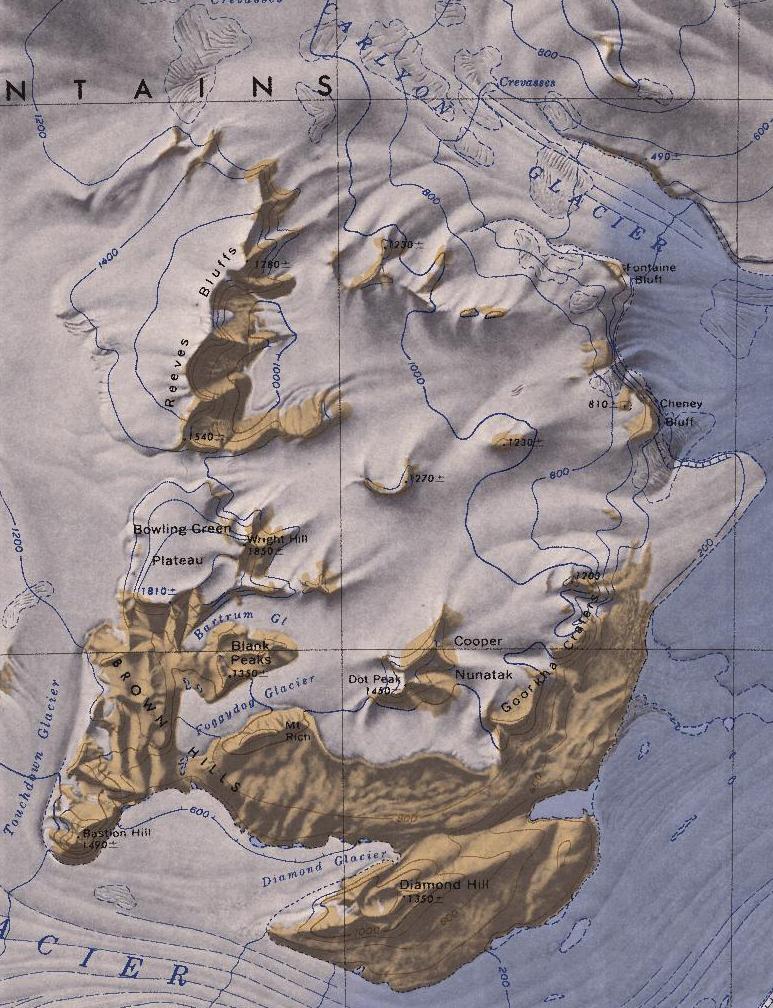

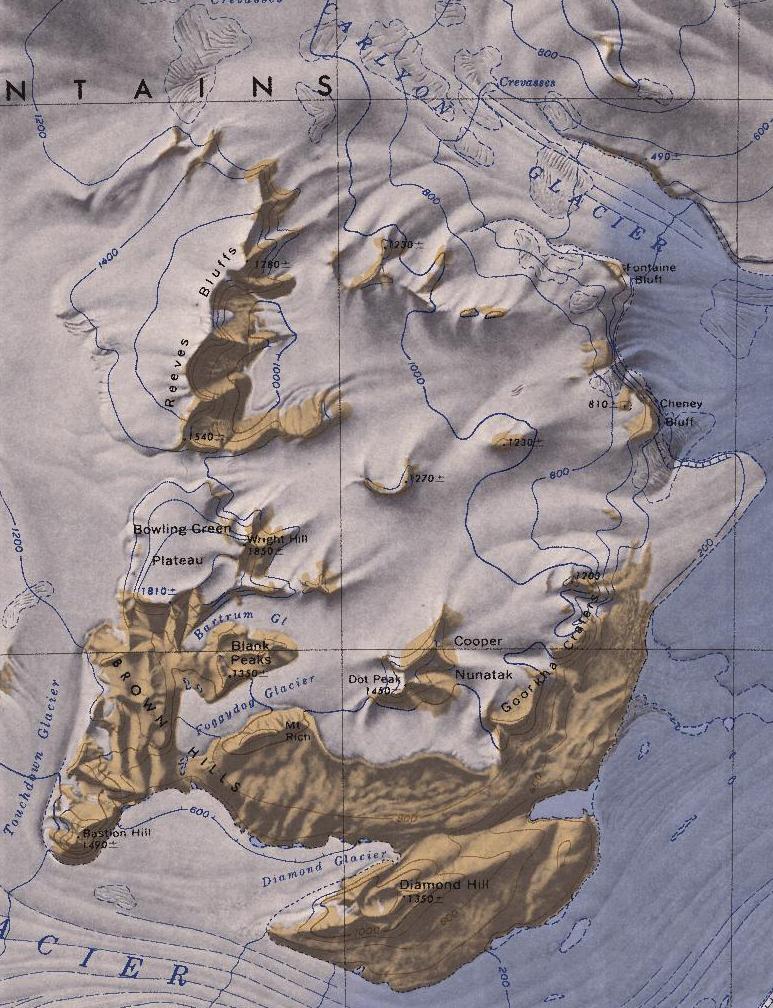

The southeast massif extends southwest from Carlyon Glacier to Darwin Glacier. The Ross Ice Shelf is to the East. Feature, from south to north, are:

The southeast massif extends southwest from Carlyon Glacier to Darwin Glacier. The Ross Ice Shelf is to the East. Feature, from south to north, are:

mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher t ...

s bounded by the Mulock and Darwin glaciers in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

.

They are south of the Worcester Range and north of the Darwin Mountains

The Darwin Mountains () are a group of mountains between the Darwin Glacier and Hatherton Glacier in Antarctica. They were discovered by the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901–04) and named for Major Leonard Darwin, at that time Honora ...

and the Britannia Range.

Early exploration and naming

Parts of the group were first viewed from theRoss Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between high ...

by the British National Antarctic Expedition (BrNAE) of 1901–04. Additional portions of these mountains were mapped by a New Zealand party of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) of 1955–1958 was a Commonwealth-sponsored expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, via the South Pole. It was the first expedition to reach the South ...

(CTAE) of 1956–58, and they were completely mapped by the United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on Mar ...

(USGS) from tellurometer

The tellurometer was the first successful microwave electronic distance measurement equipment. The name derives from the Latin ''tellus'', meaning Earth.

History

The original tellurometer, known as the Micro-Distancer MRA 1, was introduced in ...

surveys and US Navy air photos, 1959–63.

Named by the NZ-APC for Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

.

Location

The Cook Mountains are bounded by the Darwin Glacier to the south, which separates the range from the

The Cook Mountains are bounded by the Darwin Glacier to the south, which separates the range from the Darwin Mountains

The Darwin Mountains () are a group of mountains between the Darwin Glacier and Hatherton Glacier in Antarctica. They were discovered by the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901–04) and named for Major Leonard Darwin, at that time Honora ...

.

The Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between high ...

lies to the east and the Mulock Glacier

}

The Mulock Glacier () is a large, heavily crevassed glacier which flows into the Ross Ice Shelf south of the Skelton Glacier in the Ross Dependency, Antarctica.

Name

The Mulock Glacier was named by the New Zealand Antarctic Place-Names Commit ...

to the north, which separates it from the Worcester Range.

To the west is the Darwin Névé

The Darwin Glacier () is a large glacier in Antarctica. It flows from the polar plateau eastward between the Darwin Mountains and the Cook Mountains to the Ross Ice Shelf. The Darwin and its major tributary the Hatherton are often treated as one ...

and the Antarctic ice sheet

The Antarctic ice sheet is a continental glacier covering 98% of the Antarctic continent, with an area of and an average thickness of over . It is the largest of Earth's two current ice sheets, containing of ice, which is equivalent to 61% of ...

.

Glaciers

Glaciers leaving the mountains, clockwise from the north, are:Heap Glacier

. Glacier long flowing northeastward to Mulock Glacier, to the east of Henry Mesa. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-AC AN for John A. Heap, a member of the University of Michigan-Ross Ice Shelf Studies party, 1962-63.Bertoglio Glacier

. Glacier long, flowing from the Conway Range eastward betweenCape Lankester

Conway Range () is a mountain range in the Cook Mountains of Antarctica, on the west edge of the Ross Ice Shelf.

It is south of the Worcester Range.

Location

The Conway Range is in the northeast part of the Cook Mountains.

It lies between Mu ...

and Hoffman Point to the Ross Ice Shelf.

Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63.

Named by US-ACAN for Cdr. Lloyd W. Bertoglio, USN, commander of the McMurdo Station winter party, 1960.

Carlyon Glacier

. A large glacier which flows east-south-east from the névé east of Mill Mountain to the Ross Ice Shelf at Cape Murray. Mapped in 1958 by the Darwin Glacier party of the CTAE (1956-58). Named by the NZ-APC for R.A. Carlyon, who with H.H. Ayres, made up the party.Diamond Glacier

. A small distributary glacier of the Darwin Glacier, flowing east-north-east into the narrow valley on the north side ofDiamond Hill

Diamond Hill is a hill in the east of Kowloon, Hong Kong. The name also refers to the area on or adjacent to the hill. It is surrounded by Ngau Chi Wan, San Po Kong, Wong Tai Sin and Tsz Wan Shan. Its northeast is limited by the ridge. It is ...

.

Mapped by the VUWAE (1962-63) and named after Diamond Hill.

Touchdown Glacier

. A tributary of Darwin Glacier, flowing south between Roadend Nunatak and the Brown Hills. Mapped by the VUWAE (1962-63) and so named because the glacier was used as a landing site for aircraft supporting the expedition.McCleary Glacier

. A broad glacier about long, draining southward into Darwin Glacier just west of Tentacle Ridge. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-ACAN for George McCleary, public information officer on the staff of the U.S. Antarctic Projects Officer (1959-61), whose labors helped to start the Bulletin of the USAPO.Southeast massif features

The southeast massif extends southwest from Carlyon Glacier to Darwin Glacier. The Ross Ice Shelf is to the East. Feature, from south to north, are:

The southeast massif extends southwest from Carlyon Glacier to Darwin Glacier. The Ross Ice Shelf is to the East. Feature, from south to north, are:

Diamond Hill

. A conspicuous snow-free hill which is diamond shape in plan, standing east of Bastion Hill at the north side of the lower Darwin Glacier. Named by the Darwin Glacier Party of the CTAE (1956-58) which surveyed this area.Brown Hills

. A group of mainly snow-free hills in the Cook Mountains, lying north of the lower reaches of Darwin Glacier. Named for their color by the Darwin Glacier Party of theCommonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) of 1955–1958 was a Commonwealth-sponsored expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, via the South Pole. It was the first expedition to reach the South ...

(CTAE) (1956-58).

Cooper Nunatak

. A large rocky nunatak north of Diamond Hill, protruding through the ice east of the Brown Hills. Mapped by the VUWAE, 1962-63. Named for R.A. Cooper, geologist with the VUWAE, 1960-61.Dot Peak

. A small eminence, , marking the highest point of Cooper Nunatak, at the east side of the Brown Hills. Mapped by the VUWAE (1962-63) and so named because of its small size.Schoonmaker Ridge

. A jagged ridge, 4.5 nautical miles (8 km) long, that runs east from the south part ofReeves Plateau Reeves Plateau () is an inclined ice-covered plateau, 8 nautical miles (15 km) long and 4 nautical miles (7 km) wide, located north of Bowling Green Plateau and west of Reeves Bluffs in the Cook Mountains. The feature rises to 1700 m in ...

, Cook Mountains. Named by Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names

The Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (ACAN or US-ACAN) is an advisory committee of the United States Board on Geographic Names responsible for recommending commemorative names for features in Antarctica.

History

The committee was established ...

(US-ACAN) after remote sensing scientist James W. (Bill) Schoonmaker, Jr., topographic engineer, United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on Mar ...

(USGS). He spent three austral summers in Antarctica, 1972–76, with geodetic work at South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

, Byrd Station

The Byrd Station is a former research station established by the United States during the International Geophysical Year by U.S. Navy Seabees during Operation Deep Freeze II in West Antarctica. It was a year-round base until 1972, and then se ...

, Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

, Ellsworth Mountains

The Ellsworth Mountains are the highest mountain ranges in Antarctica, forming a long and wide chain of mountains in a north to south configuration on the western margin of the Ronne Ice Shelf in Marie Byrd Land. They are bisected by Minneso ...

and Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between high ...

, where he determined the precise location of geophysical sites established during the Ross Ice Shelf Project, 1973-74 field season.

Soyuz-13 Rock

. Anunatak

A nunatak (from Inuit language, Inuit ) is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They often form natural pyramidal peaks. Isolated nunataks are also cal ...

, high, located 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) southeast of Schoonmaker Ridge in the Cook Mountains.

Named after the Soviet spacecraft Soyuz 13 of December 18, 1973.

Reeves Bluffs

. A line of east-facing rock bluffs, long, situated west of Cape Murray in the Cook Mountains. Discovered by the BrNAE (1901-04) under Capt. Robert F. Scott, who gave the name "Mount Reeves," after Edward A. Reeves, Map Curator to the Royal Geographical Society, to a summit along this bluff. The bluff was mapped in detail by USGS from surveys and U.S. Navy aerial photography (1959-63). Since a prominent mountain does not rise from the bluffs, and because the name Mount Reeves is in use elsewhere in Antarctica, the US-ACAN (1965) recommended that the original name be amended and that the entire line of bluffs be designated as Reeves Bluffs. Not: Mount Reeves.Cheney Bluff

. A steep rock bluff at the south side of the mouth of Carlyon Glacier, southwest of Cape Murray. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-AC AN for Lt. Cdr. D.J. Cheney, RNZN, commander of HMNZS Rotoiti on ocean station duty between Christchurch and McMurdo Sound, 1963-64.Soyuz-18 Rock

. A distinctivenunatak

A nunatak (from Inuit language, Inuit ) is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They often form natural pyramidal peaks. Isolated nunataks are also cal ...

3 nautical miles (6 km) west of Cheney Bluff in the Cook Mountains. The feature rises to and is pyramid shaped, especially when viewed from the west. Named after the Soviet spacecraft Soyuz 18 of May 24, 1975.

Fontaine Bluff

. Bluff west of Cape Murray on the south side of Carlyon Glacier. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-ACAN for Lt. Cdr. R.K. Fontaine, USN, commander of USS Hissem on ocean station duty in support of aircraft flights between Christchurch and McMurdo Sound, 1963-64.Conway Range

. A range in the Cook Mountains between Mulock and Carlyon Glaciers. The range was discovered by the BrNAE (1901-04), but the name appears to be first used in the reports of the BrAE (1907-09).Western Features

Festive Plateau

. An ice-covered plateau over high, about , just north of Mount Longhurst in the Cook Mountains. Named by two members of the Darwin Glacier Party of the CTAE (1956-58) who spent Christmas Day 1957 on the plateau.Mill Mountain

. A large flat-topped mountain (2,730 m) forming the eastern end of Festive Plateau. This mountain was probably sighted by the BrNAE (1901-04) under Capt. Robert F. Scott, who gave the name "Mount Mill," after British Antarctic historian Hugh Robert Mill, to a summit in nearby Reeves Bluffs. This area was mapped by USGS from surveys and U.S. Navy photography (1959-63). A prominent mountain does not rise from the bluffs, and since the name Mount Mill is in use elsewhere in Antarctica, the US-ACAN (1965) altered the original name to Mill Mountain and applied it to the prominent mountain described.Bromwich Terrace

. A high relatively flat ice-capped area of about . It lies between Festive Plateau and Mount Longhurst on the north, and Starbuck Cirque and Mount Hughes on the south. At elevation, the terrace is below the adjoining Festive Plateau and below towering Mount Longhurst. It was named after David H. Bromwich of the Polar Meteorology Group,Byrd Polar Research Center

The Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center (BPCRC) is a polar, alpine, and climate research center at Ohio State University founded in 1960.

History and research

The Byrd Polar Research Center (BPRC) at Ohio State University was established in ...

, Ohio State University

The Ohio State University (Ohio State or OSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio, United States. A member of the University System of Ohio, it was founded in 1870. It is one ...

, who carried out climatological investigations of Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

for over 20 years beginning about 1978.

Starbuck Cirque

) A remarkablecirque

A (; from the Latin word ) is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by Glacier#Erosion, glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from , meaning a pot or cauldron) and ; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landform a ...

, wide, between the base of Tentacle Ridge and Mount Hughes. Named by Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names

The Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (ACAN or US-ACAN) is an advisory committee of the United States Board on Geographic Names responsible for recommending commemorative names for features in Antarctica.

History

The committee was established ...

(US-ACAN) after Michael J. Starbuck, United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on Mar ...

(USGS) cartographer who, with Roger A. Barlow, operated the seismometer and Doppler satellite receiving stations at South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

, winter 1992; member of US-NZ field team in a program to combine US and NZ geodetic networks in the McMurdo Dry Valleys

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are a row of largely Antarctic oasis, snow-free valleys in Antarctica, located within Victoria Land west of McMurdo Sound. The Dry Valleys experience extremely low humidity and surrounding mountains prevent the flow of ...

area, summer 1996–97.

Felder Peak

() Felder Peak is a peak between the terminus of McCleary Glacier and the west side of Starbuck Cirque.Mount Ayres

. A prominent mountain, high, lying south of the west end of the Finger Ridges. Climbed in December 1957 by the Darwin Glacier Party of the CTAE (1956-58). Named for H.H. Ayres, one of the two men comprising the Darwin Glacier Party.Finn Spur

. A rock spur northeast of Mount Ayres on the north side of Longhurst Plateau. It was named after Carol Finn, a geophysicist with theUnited States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on Mar ...

(USGS), who was USGS project chief on a cooperative USGS–German aeromagnetic survey over the Butcher Ridge – Cook Mountains – Darwin Névé

The Darwin Glacier () is a large glacier in Antarctica. It flows from the polar plateau eastward between the Darwin Mountains and the Cook Mountains to the Ross Ice Shelf. The Darwin and its major tributary the Hatherton are often treated as one ...

area, 1997–98, and also performed additional aeromagnetic surveys from 1991, including seasons over the West Antarctic ice sheet from 1994 as a principal investigator and USGS project chief.

Butcher Ridge

. A large, mainly ice-free ridge near the polar plateau in the west part of the Cook Mountains. The ridge is in the form of an arc, extending northwest from Mount Ayres. Named by US-ACAN for Cdr. H.K. Butcher, USN, air operations officer on the Staff of the U.S. Naval Support Force, Antarctica, during USN OpDFrz 1963 and 1964.Fault Bluff

. A notable rock bluff. high, situated northeast of Mount Longhurst. The feature was visited in the 1957-58 season by members of the Darwin Glacier Party of the CTAE, 1956-58. They applied the name which presumably refers to a geological fault at the bluff.Finger Ridges

. Several mainly ice-free ridges and spurs extending over a distance of about , east-west, in the northwest part of the Cook Mountains. The individual ridges are long and project northward from the higher main ridge. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. The descriptive name was given by the US-ACAN.Mount Gudmundson

. A mainly ice-free mountain, 2,040 m, standing northeast of Fault Bluff. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-ACAN for Julian P. Gudmundson (BUG), USN, explosive expert who wintered at Little America V in 1957. He blasted the foundation for the nuclear power plant at McMurdo Station during USNOpDFrz, 1961.Harvey Peak

. An ice-free peak, high, standing south of the Finger Ridges. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-ACAN for Paul Harvey, a member of the U.S. Army aviation support unit for Topo North and Topo South (1961-62) which conducted the tellurometer surveys.Mount Hughes

. A mountain, hugh, midway between Mount Longhurst and Tentacle Ridge. Discovered by the BrNAE (1901-04) and named for J.F. Hughes, an Honorary Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, who helped in the preparation for the expedition.Mount Longhurst

. A prominent mountain, , standing west of Mill Mountain and forming the highest point of Festive Plateau. Discovered by the BrNAE (1901-04) and named for Cyril Longhurst, secretary of the expedition.Longhurst Plateau

. A narrow, snow-covered extension of the polar plateau located just west of Mount Longhurst. Rising to , it is about long and wide, and is bounded on the south by upper Darwin Glacier and on the east by McCleary Glacier. The plateau was traversed by the Darwin Glacier Party of the CTAE in 1957-58, who named it for nearby Mount Longhurst.DeZafra Ridge

. A narrow but prominent rock ridge, long, which extends north from the northeast cliffs of Longhurst Plateau. The ridge is west of Fault Bluff and rises above then ice surface north of the plateau. It was named after Robert L. deZafra, Professor of Physics at theState University of New York, Stony Brook

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

, whose research at the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

and McMurdo Sound

The McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica, known as the southernmost passable body of water in the world, located approximately from the South Pole.

Captain James Clark Ross discovered the sound in February 1841 and named it after Lieutenant ...

provided breakthrough contributions to understanding the formation of the Antarctic ozone hole

Ozone depletion consists of two related events observed since the late 1970s: a lowered total amount of ozone in Earth, Earth's upper atmosphere, and a much larger springtime decrease in stratospheric ozone (the ozone layer) around Earth's polar ...

.

Isolated features

Isolated features in or near the range include:Henry Mesa

. A distinctive wedge-shaped mesa in extent, standing south of Mulock Glacier on the west side of Heap Glacier. The ice-covered summit, high, is flat except for a cirque which indents the north side. Mapped by the USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-ACAN for Capt. B.R. Henry, USCG, commander of the Eastwind USN OpDFrz, 1964, and commander of the U.S. ship group, OpDFrz, 1965.Kanak Peak

. Conspicuous ice-free peak, high, standing northwest of Mount Gniewek and north of the head of Carlyon Glacier in the Cook Mountains. Mapped by USGS from tellurometer surveys and Navy air photos, 1959-63. Named by US-ACAN for Lt. Cdr. R.A. Kanak, USN, commander of USS Durant on ocean station duty in support of aircraft flights between Christchurch and McMurdo Sound in USN OpDFrz 1963.Mulgrew Nunatak

. A prominentnunatak

A nunatak (from Inuit language, Inuit ) is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They often form natural pyramidal peaks. Isolated nunataks are also cal ...

, high, standing east of Tentacle Ridge in the Cook Mountains.

Mapped by the Darwin Glacier Party of the CTAE (1956-58) and named for P.O. Mulgrew, chief radio operator at Scott Base, who accompanied Sir Edmund Hillary to the South Pole.

Peter Crest

The summit ( high) of Mulgrew Nunatak in the Cook Mountains. Named after New Zealand Antarctic veteran Peter D. Mulgrew. He perished in the Air New Zealand DC10 scenic flight to Ross Island, Nov. 28, 1979, when the airplane crashed near Te Puna Roimata Peak (spring of tears peak) on the northeast slope of Mount Erebus, killing all 257 persons aboard.Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{Portal bar, Mountains, Geography, Earth sciences, Weather Mountain ranges of the Ross Dependency Hillary Coast Oates Land