Moses Dickson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

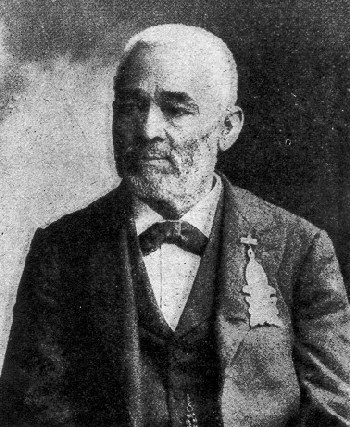

Moses Dickson (1824–1901) was an

During the

During the

The Revered Moses Dickson died of

The Revered Moses Dickson died of

Moses Dickson (1824–1901)

The Black Past

An African Life of Resistance: Moses Dickson, the Knights of Liberty and Militant Abolitionism, 1824–1857

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dickson, Moses Religious leaders from Cincinnati African-American Methodist clergy American Methodist clergy Underground Railroad people Service organizations based in the United States 1824 births 1901 deaths African-American abolitionists African-American history in St. Louis Abolitionists from Ohio Methodist abolitionists International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor 19th-century Methodists 19th-century American clergy

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

, soldier, minister, and founder of the Knights of Liberty, an anti-slavery organization that planned a slave uprising in the United States and helped African-American enslaved people to freedom through the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

. He also founded the black self-help organization The International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor and was a co-founder of Lincoln University in Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

. Moses Dickson was also active in Prince Hall Freemasonry

Prince Hall Freemasonry is a branch of North American Freemasonry created for African Americans, founded by Prince Hall on September 29, 1784. Prince Hall Freemasonry is the oldest and largest (300,000+ initiated members) predominantly African-A ...

.

Early life

Moses Dickson was born free inCincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, on April 5, 1824. His father, Robert, died when he was eight, and his mother, Hannah, died when he was fourteen. He had five sisters and three brothers. As a youth, he trained as a barber

A barber is a person whose occupation is mainly to cut, dress, groom, style and shave hair or beards. A barber's place of work is known as a barbershop or the barber's. Barbershops have been noted places of social interaction and public discourse ...

. At age sixteen, he began a three-year tour of the South, working as an itinerant barber on steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

s. What he witnessed in his travels convinced him to work for the abolition of slavery.

Knights of Liberty and slave uprising

On August 12, 1846, Dickson and eleven other young men met in the second story of an old brick house on Green St. and Seventh St. (whose name was later changed to Lucas Avenue) inSt. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

, to create a plan to end slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of List of ethnic groups of Africa, Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865 ...

. They formed a secret organization known as the Knights of Liberty which planned to initiate a national insurrection against slavery. Dickson declared "it was determined to organize the slaves throughout the south, drill them, and in ten years from that time strike for freedom" during an interview with the ''Denver Post'', reprinted in the ''Minneapolis Journal'', on July 4, 1901. The men took an oath of secrecy: "I can die, but I cannot reveal the name of any member until the slaves are free."''Minneapolis Journal''

At the end of ten years, these twelve men had grown to a network of resistance that included 42,000 men across every southern state except Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, according to Dickson. These armed men met secretly at night and drilled for the uprising. "Plans were complete for a rising," Dickson told the ''Denver Post'' reporter, "a concentration of the forces was ordered at Atlanta, GA. We expected to have nearly 200,000 men when we reached Atlanta." In July, 1857, the men were ready to march. Dickson's orders to them were to "spare women and children," parole non-combatants, treat prisoners well, and capture all ammunitions. "March, fight and conquer, or leave their bodies on the battlefield." he said.

A day was set for the national insurrection but before the time came it had become apparent to the leaders that the relationship between the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

was becoming so strained that it was decided to postpone the uprising. Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

was about to break out. Dickson decided "a higher power" was at work, and told the Knights of Liberty to "wait, have patience, hold together, not break ranks, trust in the Lord."

Having changed his mind about the uprising, Dickson spoke to the abolitionist John Brown at Davenport

Davenport may refer to:

Places Australia

*Davenport, Northern Territory, a locality

*Hundred of Davenport, cadastral unit in South Australia

**Davenport, South Australia, suburb of Port Augusta

**District Council of Davenport, former local govern ...

just before Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry with 16 black men on October 16, 1859. and tried to dissuade him, telling him it was too early. But Brown went ahead anyway.

Underground Railroad

Beginning in 1850, the network created by the Knights of Liberty was also used in theUnderground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

to help escaped slaves to freedom. A smaller secret organization, the Order of Twelve, was created in Galena, Illinois

Galena is the largest city in Jo Daviess County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. It had a population of 3,308 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. A section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Plac ...

, which used St. Louis as its headquarters and aided hundreds of slaves to freedom. Dickson raised funds for the Railroad and also directly arranged individual escape plans.

"Strange as it may seem, he told the ''Denver Post'' reporter, "some of our most generous supporters were slave owners. They did not approve of the system but they had inherited slaves and treated them so well they had no desire to run away. They had nothing to fear from the railroad." One of these men, he said, was General Cassius Clay of Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

who gave him $1,000 for the railroad. Contributions also came from England, from people who knew of the Knights and worked with them. When the Civil War broke out, "there was a shipload of arms and ammunition in Mobile harbor and another in Galveston harbor, sent to us by Englishmen" Dickson said.Denver Post, reprinted in Minneapolis Journal

Dickson also tells of watching a mother and daughter being sold on the auction block in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

and then arranging for their escape by having them "stolen," dressing them as boys, and getting them hired onto a steamer upriver and finally to freedom in Canada. Another man was helped to escape by putting him into a wooden box and shipping him out of Charleston, SC. After his escape to the north, the man called himself Henry "Box" Brown

Henry Box Brown ( – June 15, 1897) was an enslaved man from Virginia who escaped to freedom at the age of 33 by arranging to have himself mailed in a wooden crate in 1849 to abolitionists in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

For a short time, Brow ...

, attended Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, and published a memoir, ''A Life in Slavery and Freedom''.

Civil war and Reconstruction

During the

During the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, the Knights disbanded and many of their members, including Dickson, joined the Union Army. With the end of the Civil War, Dickson began to focus on education and economic development among the freed people. He joined the African Methodist Episcopalian church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Methodist denomination based in the United States. It adheres to Wesleyan–Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. It cooperates with other Methodist ...

in 1866 and became an ordained minister the following year. In 1869, Dickson became Grand Master of Grand Lodge of Missouri, Prince Hall Freemasonry

Prince Hall Freemasonry is a branch of North American Freemasonry created for African Americans, founded by Prince Hall on September 29, 1784. Prince Hall Freemasonry is the oldest and largest (300,000+ initiated members) predominantly African-A ...

. He also was highly involved in the Heroines of Jericho

Heroines of Jericho is an organization in Prince Hall Freemasonry, founded as an auxiliary organization to Holy Royal Arch Masons. Initially, only the wives, daughters, mothers, widows, and sisters of Royal Arch Masons were allowed. The organizatio ...

, an auxiliary group open to Black woman to the Holy Royal Arch

The Royal Arch is a degree of Freemasonry. The Royal Arch is present in all main masonic systems, though in some it is worked as part of Craft ('mainstream') Freemasonry, and in others in an Masonic appendant bodies, appendant ('additional') ord ...

Masons, publishing a ritual handbook for the Heroines in 1895. He started schools for black children and lobbied to obtain black teachers for black children. With other returning black Union soldiers, he was one of the co-founders of the "Lincoln Institute" (later Lincoln University) in Jefferson City, Missouri

Jefferson City, informally Jeff City, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital of the U.S. state of Missouri. It had a population of 43,228 at the 2020 United States census, ranking as the List of cities in Missouri, 16th most popu ...

, as well as a founding member of the Missouri Equal Rights League. In 1879–1880, Rev. Dickson served as President of the Refugee Relief Board which provided aid and support to the approximately 16,000 African Americans from the South who ended up in St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

on their way to Kansas and other states as part of the Exoduster movement.

In memory of the original twelve Knights of Liberty, in 1872 Dickson and his wife Mary Elizabeth Butcher Peters created the International Order of Twelve of Knights and Daughters of Tabor, an African American fraternal organization. The new organization promoted African American advancement through "Christian demeanor," the acquisition of property and wealth, morality, temperance, education, and "man's responsibility to the Supreme Being."

This organization, more commonly known as the Order of Twelve, accepted males and females on equal terms. Men and women gathered together in higher level groups and in the governing bodies of the organization, although at the local level the men held their meetings in "temples" and the women in "tabernacles" (similar to "lodges" in Freemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

). This organization was most active in the South and the lower Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

. Like many fraternal orders of the time, members received a burial policy and weekly cash payments for the sick.

Personal life

Dickson married Mary Elizabeth Butcher Peters atGalena, Illinois

Galena is the largest city in Jo Daviess County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. It had a population of 3,308 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. A section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Plac ...

on October 5, 1848. They had one daughter, Mamie Augusta. Mary Elizabeth worked in the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

, traveled with her husband on abolitionist speaking tours across the country, was co-founder of The Order of Twelve, and a "faithful and zealous worker" in the AME Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Methodist denomination based in the United States. It adheres to Wesleyan–Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. It cooperates with other Methodist ...

. She was known as Mother Dickson, while her husband was referred to as Father Dickson. Their marriage was described as an equal partnership. Mary Elisabeth died in 1891 and has been cited as an early female pioneer of black philanthropy

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

.

Death

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

on November 28, 1901. His funeral at St. Paul's AME Church in St. Louis was attended by thousands of people from all over the United States.Early, ''Ain't But A Place'' He is buried at the Father Dickson Cemetery

Father Dickson Cemetery is a historic African-American cemetery located on 845 South Sappington Road in Crestwood, St. Louis County, Missouri.

It has been listed as one of the National Register of Historic Places since October 6, 2021.

History ...

in Crestwood, Missouri

Crestwood is a city in south St. Louis County, Missouri, St. Louis County, Missouri, United States, part of the Metropolitan Statistical Area known as Greater St. Louis. The population was 12,404 at the 2020 census.

In 2011, Bloomberg Businesswe ...

.

See also

* List of African-American abolitionistsReferences

External links

Moses Dickson (1824–1901)

The Black Past

An African Life of Resistance: Moses Dickson, the Knights of Liberty and Militant Abolitionism, 1824–1857

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dickson, Moses Religious leaders from Cincinnati African-American Methodist clergy American Methodist clergy Underground Railroad people Service organizations based in the United States 1824 births 1901 deaths African-American abolitionists African-American history in St. Louis Abolitionists from Ohio Methodist abolitionists International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor 19th-century Methodists 19th-century American clergy