Montrose Academy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Montrose Academy is a

The earliest evidence of schooling in Montrose was in 1329 when

The earliest evidence of schooling in Montrose was in 1329 when  James Melville studied at Montrose in 1569 under the tutelage of Mr Andrew Milne. Melville rehearsed Calvin's Catechisms and read Virgil's

James Melville studied at Montrose in 1569 under the tutelage of Mr Andrew Milne. Melville rehearsed Calvin's Catechisms and read Virgil's

The new Montrose Academy was founded in 1815. It was partly funded by public subscription funds of £1350, adding to £1000 from Montrose Town Council. Built close to the site of the former grammar school, the foundation stone was laid on 27 February or 15 March 1815 by Mrs Ford of Finhaven.Trevor W. Johns, ''The Mid Links, Montrose, since Provost Scott'', (Montrose Review Press, 1988), p52 It existed alongside other schools including White's Free School and the local trades school, and had the largest attendance.

Montrose Academy is seen to have replaced the ancient Grammar School of Montrose which had established itself during the 16th century and absorbed all other existing burgh schools in the area. Its inception as an academy was part of a broader 18th century development in the Scottish school system towards the inclusion of more practical subjects such as navigation, drawing, arithmetic and book-keeping, alongside the traditional tuition of the

The new Montrose Academy was founded in 1815. It was partly funded by public subscription funds of £1350, adding to £1000 from Montrose Town Council. Built close to the site of the former grammar school, the foundation stone was laid on 27 February or 15 March 1815 by Mrs Ford of Finhaven.Trevor W. Johns, ''The Mid Links, Montrose, since Provost Scott'', (Montrose Review Press, 1988), p52 It existed alongside other schools including White's Free School and the local trades school, and had the largest attendance.

Montrose Academy is seen to have replaced the ancient Grammar School of Montrose which had established itself during the 16th century and absorbed all other existing burgh schools in the area. Its inception as an academy was part of a broader 18th century development in the Scottish school system towards the inclusion of more practical subjects such as navigation, drawing, arithmetic and book-keeping, alongside the traditional tuition of the

An endowment in 1891 provided facilities for a new science and art school. In 1898, after the closure of Dorward's Seminary, its building was renovated, extended and added to Montrose Academy. This provided a new assembly hall, and allowed space to complete a new gymnasium, which at the time was one of the largest in Scotland. Tuition of the classics continued into the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The curriculum expanded at the beginning of the twentieth century to include more scientific subject matter. By 1900 gymnastics and swimming were introduced to the curriculum. In 1895, the school was described as having two separate entrances for boys and girls. The classrooms were heated with open fires during the winter and the walls were decorated with pictures, photographs and maps gifted by former pupils. There was also a preparatory school attached - Montrose Academy Elementary School, which existed until the 1970s. In 1932 the local Townhead School, which taught commercial and technical subjects, became part of Montrose Academy. It was fully amalgamated by the 1950s.

Universal secondary education was enacted in 1936 but schools were split on a meritocratic basis, between "junior secondary schools" leading to no qualifications and "senior secondary schools", like Montrose Academy, where pupils would earn a leaving certificate and university entrance. Montrose Academy eventually became a state school in 1965 after the introduction of comprehensive schools throughout Scotland.

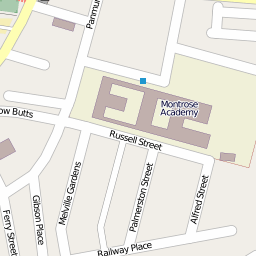

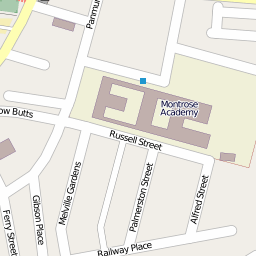

Montrose Academy is a community school, and its catchment area extends to the surrounding villages of Craigo, Hillside and Ferryden. The feeder schools are Borrowfield Primary School, Ferryden Primary School, Lochside Primary School, Southesk Primary School, St Margaret's Primary School and Rosemount.

An endowment in 1891 provided facilities for a new science and art school. In 1898, after the closure of Dorward's Seminary, its building was renovated, extended and added to Montrose Academy. This provided a new assembly hall, and allowed space to complete a new gymnasium, which at the time was one of the largest in Scotland. Tuition of the classics continued into the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The curriculum expanded at the beginning of the twentieth century to include more scientific subject matter. By 1900 gymnastics and swimming were introduced to the curriculum. In 1895, the school was described as having two separate entrances for boys and girls. The classrooms were heated with open fires during the winter and the walls were decorated with pictures, photographs and maps gifted by former pupils. There was also a preparatory school attached - Montrose Academy Elementary School, which existed until the 1970s. In 1932 the local Townhead School, which taught commercial and technical subjects, became part of Montrose Academy. It was fully amalgamated by the 1950s.

Universal secondary education was enacted in 1936 but schools were split on a meritocratic basis, between "junior secondary schools" leading to no qualifications and "senior secondary schools", like Montrose Academy, where pupils would earn a leaving certificate and university entrance. Montrose Academy eventually became a state school in 1965 after the introduction of comprehensive schools throughout Scotland.

Montrose Academy is a community school, and its catchment area extends to the surrounding villages of Craigo, Hillside and Ferryden. The feeder schools are Borrowfield Primary School, Ferryden Primary School, Lochside Primary School, Southesk Primary School, St Margaret's Primary School and Rosemount.

The original Montrose Academy building, designed by David Logan is connected to its wings by screens of

The original Montrose Academy building, designed by David Logan is connected to its wings by screens of  In 1955 plans were unveiled for new buildings to be added to the old Montrose Academy. Houses in the Academy Square were demolished and £250,000 set aside. The 1961 extension, officially declared open on 23 October of that year, brought into use two three-storey blocks attached to the 1841 additions. The major work of the last Extension in 1988-89 was the building of the East Wing, a two-storey block linked to the old West Wing by walkways. It contains a number of teaching areas in addition to a Library, Communications Studio, Social Areas and Dining Room. In 2000, the 'Millenium Garden' was developed in the West Wing courtyard.

The most recent significant alterations were made in 2006. The East Annexe building which was once the Montrose Academy Elementary has been demolished. It housed the Drama and Music departments which have since been relocated to the main building. Music is now taught in the West Wing and Drama in the East Wing. During this relocation improvements were made to classroom space for IT, Drama and Music. In addition, £64,000 was spent on updating Home Economics classrooms. Science labs were refurbished in 2010.

In 1955 plans were unveiled for new buildings to be added to the old Montrose Academy. Houses in the Academy Square were demolished and £250,000 set aside. The 1961 extension, officially declared open on 23 October of that year, brought into use two three-storey blocks attached to the 1841 additions. The major work of the last Extension in 1988-89 was the building of the East Wing, a two-storey block linked to the old West Wing by walkways. It contains a number of teaching areas in addition to a Library, Communications Studio, Social Areas and Dining Room. In 2000, the 'Millenium Garden' was developed in the West Wing courtyard.

The most recent significant alterations were made in 2006. The East Annexe building which was once the Montrose Academy Elementary has been demolished. It housed the Drama and Music departments which have since been relocated to the main building. Music is now taught in the West Wing and Drama in the East Wing. During this relocation improvements were made to classroom space for IT, Drama and Music. In addition, £64,000 was spent on updating Home Economics classrooms. Science labs were refurbished in 2010.

There are small gymnasia inside the school and playing grounds outside. The facilities of the adjacent Sports Centre are used by the school for physical education classes. A new swimming pool is being built attached to the Sports Centre; work started in 2011 and the project will be completed by October 2012. During this time improvements are being made at Montrose Academy including the installation of a small gym, new flooring, changing rooms and showers to the cost of £140,000.

There are small gymnasia inside the school and playing grounds outside. The facilities of the adjacent Sports Centre are used by the school for physical education classes. A new swimming pool is being built attached to the Sports Centre; work started in 2011 and the project will be completed by October 2012. During this time improvements are being made at Montrose Academy including the installation of a small gym, new flooring, changing rooms and showers to the cost of £140,000.

School websiteMontrose Academy on Scottish Schools Online

(Angus Council)

Angus Secondary School Attainment levels 2007-2009

(Angus Council) {{authority control Educational institutions established in 1815 Category B listed buildings in Angus, Scotland Secondary schools in Angus, Scotland 1815 establishments in Scotland History of Angus, Scotland Neoclassical architecture in Scotland Montrose, Angus

coeducational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to ...

secondary school in Montrose Angus. The School now teaches people from ages 11–18.

It became a comprehensive school

A comprehensive school is a secondary school for pupils aged 11–16 or 11–18, that does not select its intake on the basis of academic achievement or aptitude, in contrast to a selective school system where admission is restricted on the basis ...

in the mid-fifties and was one of a pair of Scottish schools which formed a country-wide trial of comprehensive schooling in Scotland. It serves the surrounding local community with a roll of around 900 students

A student is a person enrolled in a school or other educational institution, or more generally, a person who takes a special interest in a subject.

In the United Kingdom and most commonwealth countries, a "student" attends a secondary school ...

and a staff of 79. Most pupils come from the associated primary school

A primary school (in Ireland, India, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, South Africa, and Singapore), elementary school, or grade school (in North America and the Philippines) is a school for primary ...

s of Borrowfield, Ferryden, Lochside, Rosemount, Southesk and St Margaret's. A number of pupils come from outside the catchment area.

History

The Grammar School

The earliest evidence of schooling in Montrose was in 1329 when

The earliest evidence of schooling in Montrose was in 1329 when Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (), was King of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329. Robert led Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against Kingdom of Eng ...

gave twenty shillings to "David of Montrose in aid of the schools".John Strong, "The Development of Secondary Education in Scotland", ''The School Review'', Vol. 15, No. 8 (Oct. 1907), pp. 594-607 The name of John Cant or Kant, appears on a deed dated 26 September 1492 as "Master of Arts and Rector of the Parish Church of Logy in Montrose Parish" and is believed to be an early record of a public school in the Montrose area. The grammar school was founded in the 16th century, although the precise date of establishment is unknown.Great Britain. Education Commission (Scotland)., ''Report by Her Majesty's Commissioners appointed to inquire into schools in Scotland, Volume 4'', (H.M. Stationery Office, 1868) Originally the grammar school was established close to the parish church and it was a requirement of the schoolmaster to read lessons in the church, although the practice was waning by the late eighteenth century.James G. Low, ''The Grammar School of Montrose'', (J. Balfour & Co, 1936), p47

The Grammar School of Montrose is reputed to have been the first school in Scotland to teach Classical Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archa ...

. This was made possible when John Erskine of Dun

John Erskine of Dun (1509–1591) was a Scottish religious reformer.

Biography

The son of Sir John Erskine, Laird of Dun, he was educated at King's College, University of Aberdeen. At the age of twenty-one Erskine was the cause – probably by ...

, the then Provost of Montrose and patron of the school, brought Pierre de Marsilliers to Scotland in 1534 and founded a Greek school. Other teachers from France followed. The introduction of Greek at Montrose is understood to have hastened the Reformation in Scotland. In the 1530s the Protestant reformer, George Wishart

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant martyrs burned at the stake as a heretic.

George Wishart was the son of James and brother of Sir John of Pitarrow ...

began to teach at the school.Ian Cumming, "The Scottish Education of James Mill" in ''History of Education Quarterly'', Vol.2, No.3(Sept. 1962), p155 Wishart came to be known as "the Schoolmaster of Montrose". He taught and circulated copies of the Greek Testament

(''The New Testament in Greek'') is a critical edition of the New Testament in its original Koine Greek published by ''Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft'' (German Bible Society), forming the basis of most modern Bible translations and biblical crit ...

amongst his pupils and fled to England in 1538 when investigated for heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

by William Chisholm, the then Bishop of Brechin

The Bishop of Brechin is a title held successively, since c. 1150: (firstly) by bishops of the Catholic church until the Reformation of 1560; (secondly) by bishops of the Church of Scotland until that church declared itself presbyterian in ...

. It is likely that on his return to Scotland he taught John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

Greek before returning to teach in Montrose in 1544.

The grammar school was renowned enough as a seminary to attract such distinguished men as James Melville (1556–1614)

James Melville (26 July 1556 – 1614) was a Scottish divine and reformer, son of the laird of Baldovie, in Forfarshire.

Life

Melville was born at Baldovie in Angus in 1556 and he was educated at Montrose and St Leonard's College, St Andr ...

and his uncle, Andrew Melville

Andrew Melville (1 August 1545 – 1622) was a Scottish scholar, theologian, poet and religious reformer. His fame encouraged scholars from the European continent to study at Glasgow and St. Andrews.

He was born at Baldovie, on 1 August 154 ...

. Andrew Melville

Andrew Melville (1 August 1545 – 1622) was a Scottish scholar, theologian, poet and religious reformer. His fame encouraged scholars from the European continent to study at Glasgow and St. Andrews.

He was born at Baldovie, on 1 August 154 ...

was taught Latin at the grammar school by Schoolmaster Thomas Anderson. He studied the original Greek of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

under Pierre de Marsilliers in 1557 before passing to the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

in 1559. His proficiency in Greek astonished the professors there who had no knowledge of the language. Melville later became a noted theologian and distinguished scholar of Classical Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archa ...

and Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

.

James Melville studied at Montrose in 1569 under the tutelage of Mr Andrew Milne. Melville rehearsed Calvin's Catechisms and read Virgil's

James Melville studied at Montrose in 1569 under the tutelage of Mr Andrew Milne. Melville rehearsed Calvin's Catechisms and read Virgil's Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek language, Greek word , ''geōrgiká'', i.e. "agricultural hings) the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from bei ...

amongst other works. He used these words to describe his years of instruction: " The maister of the scholl, was a lerned, honest, kynd man, whom also for thankfulness I name, Mr. Andro Miln. I never got a stroke of his hand; howbeit, I committed twa stupid faults, as it were with fire and sword :—Having the candle in my hand, on a winter night, before six o'clock, in the school, sitting in the class, bairnly and negligently playing with the bent, with which the floor was strewed, it kindled, so that we had much ado to put it out with our feet. The other was being molested by a condisciple, who cut the strings of my pen and ink-horn with his pen-knife; I aiming with my pen-knife to his legs to fley him; he feared, and lifting now a leg and now the other, rushed on his leg upon my knife, and struck himself a deep wound in the shin of the leg, which was a quarter of a year in curing. In the time of the trying of the matter, he saw me so humble, so feared, so grieved, yield so many tears, and by fasting and mourning at the school all day, that he said he could not find in his heart to punish me farther. But my righteous God let me not slip that fault, but gave me a warning, and remembrance what it was to be denied with blood, although negligently; for within a short space, after I had caused a cutler, newly come to the town, to polish and sharp the same pen-knife, and had bought a pennyworth of apples, and cutting and eating the same in the links, as I put the slice in my mouth, I began to lope up upon a little sand brae, having the pen-knife in my right hand, I fell, and struck myself, missing my belly, an inch deep in the inward side of the left knee, even to the bean, whereby the equity of God's judgment, and my conscience struck me so, that I was the more wary of knives all my days."

George Gledstanes

George Gledstanes (or Gladstanes; c. 1562 – 1615Alan R. MacDonald‘Gledstanes , George (c.1562–1615)’ ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004) was an Archbishop of St Andrews during the seventeenth c ...

was master in 1586–7, a teacher of languages and Reader in the parish church. David Lindsay was appointed master around 1594 before becoming master at Dundee Grammar School

The High School of Dundee is a private, co-educational, day school in Dundee, Scotland, which provides nursery, primary and secondary education to just over one thousand pupils. Its foundation has been dated to 1239, and it is the only private sc ...

. He was followed by James Lichton, appointed in 1614.James G. Low, ''The Grammar School of Montrose'', (J. Balfour & Co, 1936), p32 Alexander Petrie, made master in 1622, received a salary of 25 merks

The merk () is a long-obsolete Scotland, Scottish silver coin. Originally the same word as a Mark (currency), money mark of silver, the merk was in circulation at the end of the 16th century and in the 17th century. It was originally valued at 1 ...

per quarter for Candlemass, Lamass, and Hallowmass. Robert Graham became master in August 1638 and remained until 1644. By this time the school was increasing in numbers and an assistant master was employed in 1639. Succeeding Graham were William Clyd (6 May 1643 – 8 November 1643); John Nicol (1643–1645); John Cargill (1645-July 1656) and John Strachan (22 September 1656 – 1659). James Wishart was master from 1659 until his death in 1684. William Langmuir or Langmoor was appointed on 2 January 1684 and was in his post until 1704, when Robert Strachan took over as master. In 1686 a library was established at the Grammar School, which contained a number of rare books. On 28 June 1710 Robert Spence became master, then James Stewart in 1717 and Patrick Renny on 16 June 1725. Hugh Christie, on 10 June 1752, was the first headmaster of the school to be granted the title "rector". His successor David Valentyne was rector from 20 July 1766 until 19 October 1806.

In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, an "English School" opened in the town. The school taught music, French, writing, arithmetic, book-keeping, geometry and navigation. By the late eighteenth century, the old Grammar School was in ruins. Construction of the 'New Schools', designed by Andrew Barrie, commenced in 1787 and was completed the following year. The buildings were constructed on the Mid Links, an area of parkland in the town, and contained separate accommodation for the Grammar School, English School and Writing School. Between the ruin of the old Grammar School and the building of the 'New Schools', the Grammar School operated from rooms in the Town House.

The teaching of French is noted in the early history of the Grammar School; German was not taught until the beginning of the nineteenth century. Painting was introduced as a subject in 1816.

The educational establishment in Montrose was one of the most renowned burgh schools in Scotland which provided a preparatory education for university study. It was especially well regarded in teaching classics.

Montrose Academy

The new Montrose Academy was founded in 1815. It was partly funded by public subscription funds of £1350, adding to £1000 from Montrose Town Council. Built close to the site of the former grammar school, the foundation stone was laid on 27 February or 15 March 1815 by Mrs Ford of Finhaven.Trevor W. Johns, ''The Mid Links, Montrose, since Provost Scott'', (Montrose Review Press, 1988), p52 It existed alongside other schools including White's Free School and the local trades school, and had the largest attendance.

Montrose Academy is seen to have replaced the ancient Grammar School of Montrose which had established itself during the 16th century and absorbed all other existing burgh schools in the area. Its inception as an academy was part of a broader 18th century development in the Scottish school system towards the inclusion of more practical subjects such as navigation, drawing, arithmetic and book-keeping, alongside the traditional tuition of the

The new Montrose Academy was founded in 1815. It was partly funded by public subscription funds of £1350, adding to £1000 from Montrose Town Council. Built close to the site of the former grammar school, the foundation stone was laid on 27 February or 15 March 1815 by Mrs Ford of Finhaven.Trevor W. Johns, ''The Mid Links, Montrose, since Provost Scott'', (Montrose Review Press, 1988), p52 It existed alongside other schools including White's Free School and the local trades school, and had the largest attendance.

Montrose Academy is seen to have replaced the ancient Grammar School of Montrose which had established itself during the 16th century and absorbed all other existing burgh schools in the area. Its inception as an academy was part of a broader 18th century development in the Scottish school system towards the inclusion of more practical subjects such as navigation, drawing, arithmetic and book-keeping, alongside the traditional tuition of the Classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

.Bob Harris, "Cultural Change in Provincial Scottish Towns, c.1700-1820", ''The Historical Journal'', Vol.54, No.1 (2011), p119 This was seen in other Scottish provincial towns and reflected a commitment to learning which was "rooted in the past, but re-energized and adapted" due to the effects of urban growth and the rise of a commercial elite. Academies were concentrated in the industrial towns of the east. The wide curricular provision was such that an 1866 report complained that "Classics do not occupy a prominent place, and nothing else has been substituted in the way of sound and systematic training".

Academies were initially supplementary but eventually superseded the old grammar schools, as had occurred in Montrose. The foundation of Montrose Academy came 55 years after that of the very first academy in Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

in 1760. The pupils were required to pay fees, which funded teachers' salaries. Sometimes, as in the case of James Mill, poor boys were sponsored by local ministers or benevolent landowners. In the mid-nineteenth century, a bequest left by John Erskine of Saint James Parish, Jamaica

St. James is a suburban parish, located on the north-west end of the island of Jamaica in the county of Cornwall. Its capital is Montego Bay (derived from the Spanish word ''manteca'' (lard) because many wild hogs were found there, from which ...

to the sum of £3000, provided education for eight orphaned boys.

Around 1815 James Calvert was rector of the Grammar School. John Rintoul taught Reading and Grammar, James Norval taught Grammar and Geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, Robert Baird and William Beattie taught Writing and Arithmetic, and Robert Munro taught drawing.David Mitchell, ''The History of Montrose'' (1866), p44 As was commonly practiced at the time, James Calvert had 20-30 pupils boarding in his house between 1815 and 1820. The first rector of Montrose Academy after it was formally established is said to have been called Johnston. John Pringle Nichol

John Pringle Nichol Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, FRSE FRAS (13 January 1804 – 19 September 1859) was a Scotland, Scottish educator, phrenologist, astronomer and economist who did much to popularise astronomy in a manner that appe ...

was rector from 1828 to 1834 and was qualified to teach Classical Literature, English Literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian languages, Anglo-Frisian d ...

, French, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

, Spanish, Geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, History

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

, Natural History

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, Geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

, Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, Chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, Natural Philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

, Anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

, Physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

, Animal Mechanics, Moral Philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

and Political Economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

. He was later appointed Professor of Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

at the University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow (abbreviated as ''Glas.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals; ) is a Public university, public research university in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded by papal bull in , it is the List of oldest universities in continuous ...

in 1836, finding fame through his essays and lectures.

In 1832 the Montrose Grammar School building was acquired by the Board of Health

A local board of health (or simply a ''local board'') was a local authority in urban areas of England and Wales from 1848 to 1894. They were formed in response to cholera epidemics and were given powers to control sewers, clean the streets, regulat ...

for use as a cholera hospital, resulting in the transfer of teachers to Montrose Academy. The 1841 Census reveals that Rev. Alexander Stewart was rector of Montrose Academy while James Calvert was "Rector of the Grammar School". It is evident that both schools existed as independent institutions but within the same building. Yet by 1846 it is clear that Montrose Academy had come to replace the old Grammar School, and it is mentioned as the prominent educational institution in the town. There was no formalised leadership of the school for some time. In 1845, the second Statistical Account recorded that the rector of the school taught mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

and French and that there were two teachers of English; two teachers of writing and arithmetic and two for Latin. The school was then attended by 347 pupils. By the mid-nineteenth century, the staff consisted of the rector, the rector's assistant, four masters and a mistress. Staff from around this time include Alexander Madoland (Drawing Master from 1843 to 1881); and Alex Monfries (English Master in 1867). Reading of the Bible was considered an obligatory part of learning.

Montrose Academy remained a burgh school until 1872 when it was designated "a higher class public school" and the best in its region because it was an exclusive fee-paying school which provided higher instruction in such subjects as Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, modern languages

A modern language is any human language that is currently in use as a native language. The term is used in language education to distinguish between languages which are used for day-to-day communication (such as French and German) and dead clas ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

. The 1872 Education Act transferred management of all burgh schools from town councils to elected school boards. Montrose Academy received £300 annually, on the condition that it admitted 25 free scholars by examination. From 1888 further reform brought in a Scottish leaving certificate, to be examined by university professors. Girls and boys were taught together in Latin classes. In 1895, girls were particularly proficient in German classes and boys often pursued the study of Medicine. Montrose Academy continued to provide preparatory education until the mid-twentieth century. The intake then was predominantly middle class.

Extension

An endowment in 1891 provided facilities for a new science and art school. In 1898, after the closure of Dorward's Seminary, its building was renovated, extended and added to Montrose Academy. This provided a new assembly hall, and allowed space to complete a new gymnasium, which at the time was one of the largest in Scotland. Tuition of the classics continued into the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The curriculum expanded at the beginning of the twentieth century to include more scientific subject matter. By 1900 gymnastics and swimming were introduced to the curriculum. In 1895, the school was described as having two separate entrances for boys and girls. The classrooms were heated with open fires during the winter and the walls were decorated with pictures, photographs and maps gifted by former pupils. There was also a preparatory school attached - Montrose Academy Elementary School, which existed until the 1970s. In 1932 the local Townhead School, which taught commercial and technical subjects, became part of Montrose Academy. It was fully amalgamated by the 1950s.

Universal secondary education was enacted in 1936 but schools were split on a meritocratic basis, between "junior secondary schools" leading to no qualifications and "senior secondary schools", like Montrose Academy, where pupils would earn a leaving certificate and university entrance. Montrose Academy eventually became a state school in 1965 after the introduction of comprehensive schools throughout Scotland.

Montrose Academy is a community school, and its catchment area extends to the surrounding villages of Craigo, Hillside and Ferryden. The feeder schools are Borrowfield Primary School, Ferryden Primary School, Lochside Primary School, Southesk Primary School, St Margaret's Primary School and Rosemount.

An endowment in 1891 provided facilities for a new science and art school. In 1898, after the closure of Dorward's Seminary, its building was renovated, extended and added to Montrose Academy. This provided a new assembly hall, and allowed space to complete a new gymnasium, which at the time was one of the largest in Scotland. Tuition of the classics continued into the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The curriculum expanded at the beginning of the twentieth century to include more scientific subject matter. By 1900 gymnastics and swimming were introduced to the curriculum. In 1895, the school was described as having two separate entrances for boys and girls. The classrooms were heated with open fires during the winter and the walls were decorated with pictures, photographs and maps gifted by former pupils. There was also a preparatory school attached - Montrose Academy Elementary School, which existed until the 1970s. In 1932 the local Townhead School, which taught commercial and technical subjects, became part of Montrose Academy. It was fully amalgamated by the 1950s.

Universal secondary education was enacted in 1936 but schools were split on a meritocratic basis, between "junior secondary schools" leading to no qualifications and "senior secondary schools", like Montrose Academy, where pupils would earn a leaving certificate and university entrance. Montrose Academy eventually became a state school in 1965 after the introduction of comprehensive schools throughout Scotland.

Montrose Academy is a community school, and its catchment area extends to the surrounding villages of Craigo, Hillside and Ferryden. The feeder schools are Borrowfield Primary School, Ferryden Primary School, Lochside Primary School, Southesk Primary School, St Margaret's Primary School and Rosemount.

Building

The original Montrose Academy building, designed by David Logan is connected to its wings by screens of

The original Montrose Academy building, designed by David Logan is connected to its wings by screens of Ionic columns

The Ionic order is one of the three canonic orders of classical architecture, the other two being the Doric and the Corinthian. There are two lesser orders: the Tuscan (a plainer Doric), and the rich variant of Corinthian called the composite ...

which were added in 1841 and were designed to harmonise with the existing frontage. The distinctive facade is the only part of the original building to survive but is a fine example of Scottish architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

in the Neo-Classical style. It has been Category B listed since 1971 by Historic Scotland.

The original 1815 building contained three classrooms on the ground floor, and three on the floor above with a room contained within the dome. The 1841 addition of two ground floor wings situated north and south of the original facade, provided more space for teaching.

Further improvements were made during the twentieth century expansion of the school. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

Montrose Academy's copper dome was covered in gold leaf as a war memorial, paid for by Miss Blanche Mearns. In the 1960s two memorials were added to the east exterior wall of the Assembly Hall, bearing the names of former students who had died in both world wars.

In 1955 plans were unveiled for new buildings to be added to the old Montrose Academy. Houses in the Academy Square were demolished and £250,000 set aside. The 1961 extension, officially declared open on 23 October of that year, brought into use two three-storey blocks attached to the 1841 additions. The major work of the last Extension in 1988-89 was the building of the East Wing, a two-storey block linked to the old West Wing by walkways. It contains a number of teaching areas in addition to a Library, Communications Studio, Social Areas and Dining Room. In 2000, the 'Millenium Garden' was developed in the West Wing courtyard.

The most recent significant alterations were made in 2006. The East Annexe building which was once the Montrose Academy Elementary has been demolished. It housed the Drama and Music departments which have since been relocated to the main building. Music is now taught in the West Wing and Drama in the East Wing. During this relocation improvements were made to classroom space for IT, Drama and Music. In addition, £64,000 was spent on updating Home Economics classrooms. Science labs were refurbished in 2010.

In 1955 plans were unveiled for new buildings to be added to the old Montrose Academy. Houses in the Academy Square were demolished and £250,000 set aside. The 1961 extension, officially declared open on 23 October of that year, brought into use two three-storey blocks attached to the 1841 additions. The major work of the last Extension in 1988-89 was the building of the East Wing, a two-storey block linked to the old West Wing by walkways. It contains a number of teaching areas in addition to a Library, Communications Studio, Social Areas and Dining Room. In 2000, the 'Millenium Garden' was developed in the West Wing courtyard.

The most recent significant alterations were made in 2006. The East Annexe building which was once the Montrose Academy Elementary has been demolished. It housed the Drama and Music departments which have since been relocated to the main building. Music is now taught in the West Wing and Drama in the East Wing. During this relocation improvements were made to classroom space for IT, Drama and Music. In addition, £64,000 was spent on updating Home Economics classrooms. Science labs were refurbished in 2010.

Rectors of Montrose Academy

Former Rector John Strong (1868–1945), who later became Rector of theRoyal High School, Edinburgh

The Royal High School (RHS) of Edinburgh is a co-educational school administered by the City of Edinburgh Council. The school was founded in 1128 and is one of the oldest schools in Scotland. It serves around 1,400 pupils drawn from four feeder pr ...

then professor of education at the University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is a public research university in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It was established in 1874 as the Yorkshire College of Science. In 1884, it merged with the Leeds School of Medicine (established 1831) and was renamed Y ...

, wrote about the history of Montrose Academy. His son, Sir Kenneth Strong

Major-General Sir Kenneth William Dobson Strong (9 September 1900 – 11 January 1982) was a senior officer of the British Army who served in the Second World War, rising to become Director General of Intelligence. A graduate of the Royal Mil ...

(1900–1982), who attended the school, was a Major-General in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

, commander of Royal Scots Fusiliers

The Royal Scots Fusiliers was a line infantry regiment of the British Army that existed from 1678 until 1959 when it was amalgamated with the Highland Light Infantry (City of Glasgow Regiment) to form the Royal Highland Fusiliers (Princess Ma ...

in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, Chief of Intelligence for U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

and Director-General of Intelligence for Ministry of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

(1964–66).

Former teachers

* the religious reformerGeorge Wishart

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant martyrs burned at the stake as a heretic.

George Wishart was the son of James and brother of Sir John of Pitarrow ...

(1513–46)

* the astronomer John Pringle Nichol

John Pringle Nichol Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, FRSE FRAS (13 January 1804 – 19 September 1859) was a Scotland, Scottish educator, phrenologist, astronomer and economist who did much to popularise astronomy in a manner that appe ...

(1804–1859)

Organisation

Green recycling facilities were set up around the school in 2009. It has become the firstFairtrade

A fair trade certification is a product certification within the market-based movement of fair trade. The most widely used fair trade certification is FLO International's, the International Fairtrade Certification Mark, used in Europe, Africa ...

school in Angus

Angus may refer to:

*Angus, Scotland, a council area of Scotland, and formerly a province, sheriffdom, county and district of Scotland

* Angus, Canada, a community in Essa, Ontario

Animals

* Angus cattle, various breeds of beef cattle

Media

* ...

.

Structure

Montrose Academy is headed by the rector and three deputy rectors. The school departments are Business Education and Computing, English, Expressive Arts (Art, Drama, Music), Health (Home Economics, Physical Education), Mathematics, Modern Languages (French, German, Spanish), Social Subjects (Geography, History, Modern Studies, Religious Education), Science (Biology, Chemistry, Physics), Support for Learning and Technical Education (Craft and Design, Graphic Communication and Technological Studies). Each department is headed by a Principal Teacher. There are a number of technical and support staff. The school is divided organisationally into the Junior School (S1-S3) and Senior School (S4-S6).Pastoral care

A 2004 inspector's report noted that the school was "very welcoming". In general the school aims to foster the potential of each individual child as part of a holistic approach to education. It issues a code of conduct which states that pupils should be punctual and considerate of others; behave sensibly; dress appropriately for school; use their common sense; be prepared for class and work hard. Though the school is non-denominational it arranges for four chaplains from local churches, both Protestant and Catholic, to occasionally take assemblies. But reserves the right of parents to withdraw their children from instruction in religious subjects. All year groups have classes in "Social Education" which focuses on health, moral issues, personal and careers development. Careers Officers in the school provide advice on academic decision-making. The school provides clothing grants and bursaries to those in financial need. A 2010 Inspectors' Report noted the school's strengths in supporting children during the transition from primary to secondary school, and the involvement of its pupils in fundraising activities. However it stated that "a number of young people" were unhappy about how the school dealt with poor behaviour and bullying.Academics

Performance

The strongest academic performance has been inBiology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, Chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

and Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

. The number of students progressing to university is generally consistent with the national average and in 2010 was above the national average. In 2007 it was ranked 272 in Scotland for Standard Grade

Standard Grades were Scotland's educational qualifications for students aged around 14 to 16 years. Introduced in 1986, the Grades were replaced in 2013 with the Scottish Qualifications Authority's National exams in a major shake-up of Scotland's ...

exam results from around 460 state schools. Standard Grade and Higher pass rates since 2008 have dropped slightly below the national average. However numbers passing Advanced Higher level examinations were above the national average for 2010. The 2010 report noted that pupils in the Senior School tended to perform less well and that "at all stages, young people could attain and achieve more".

School attendance is above the national average.

Curriculum

Montrose Academy follows the Scottish education system and theCurriculum for Excellence

''Curriculum for Excellence'' (Scottish Gaelic: ''Curraicealam airson Sàr-mhathais'') is the national curriculum in Scotland, used by Scottish schools for learners ages 3–18. The implementation of ''Curriculum for Excellence'' is overseen by ...

. In S1-S2 pupils take courses from all departments. From S3 pupils are still given a broad education but are allowed electives in the expressive arts, social sciences and other electives. This prepares them to choose 4 subjects, not including Maths and English which are mandatory, to take in S4 usually at a National 5 level. Pupils in the Senior School choose 5 from a range of Higher grade subjects where Advanced Highers (a maximum of 3) can be taken in S6. However teaching of Advanced Highers is less comprehensive. In 2009 Angus Council

Angus Council is the Local government in Scotland, local authority for Angus, Scotland, Angus, one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

History

The first election to Angus District Council was held in 1974, initially operating as a shadow authori ...

announced that it was dropping Advanced Higher Business Management, History and Modern Studies from the curriculum. However this was not enforced as pupils are still learning those subjects currently. Pupils in the Senior School are able to study Higher Psychology through day classes at Angus College.

Academic prizes

The school awards theDux

''Dux'' (, : ''ducēs'') is Latin for "leader" (from the noun ''dux, ducis'', "leader, general") and later for duke and its variant forms (doge, duce, etc.). During the Roman Republic and for the first centuries of the Roman Empire, ''dux'' coul ...

medal yearly, an award which has been said to have been first instituted in honour of Alexander Burnes

Captain Sir Alexander Burnes (16 May 1805 – 2 November 1841) was a Scottish explorer, military officer and diplomat associated with the Great Game. He was nicknamed Bokhara Burnes for his role in establishing contact with and expl ...

; the medal itself is inscribed with the name of James Burnes (1801–1862), whose brother Alexander (1805–1841) was killed in Afghanistan. The Dux medal has been awarded since at least 1896 but possibly for much longer - the medal is inscribed 'Jacobo Burnes Indiam Relinquit MDCCCXLIX' and 'Academiae Montis Rosarum Fratres Latomi Bombaiensis' which suggests that the original medal was presented to James Burnes on leaving India in 1849 by brother freemasons from Montrose Academy living in Bombay. Other long-standing prizes include the Warrack Essay Prize (gifted by Sir James Howard Warrack), Duke Medal (for Mathematics) and the Henry Steele Prize (awarded for History). A number of prizes are sponsored by local businesses and organisations. School Colours are awarded for representation of the school at a national level in sport or other activities.

Educational links

In 2006 links were established with a new sister school in China following the twinning ofAngus

Angus may refer to:

*Angus, Scotland, a council area of Scotland, and formerly a province, sheriffdom, county and district of Scotland

* Angus, Canada, a community in Essa, Ontario

Animals

* Angus cattle, various breeds of beef cattle

Media

* ...

with Yantai City. Twinning arrangements have been made in other Angus schools, Webster's High School and Brechin High School

Brechin High School is a non-denominational secondary school in Brechin, Angus, Scotland.

Admissions

It has approximately 660 students. The school has a relationship with the town's Brechin#Brechin Cathedral, cathedral stretching back to the ear ...

. It is hoped that these ties will enable the teaching of Mandarin Chinese

Mandarin ( ; zh, s=, t=, p=Guānhuà, l=Mandarin (bureaucrat), officials' speech) is the largest branch of the Sinitic languages. Mandarin varieties are spoken by 70 percent of all Chinese speakers over a large geographical area that stretch ...

as part of future plans. From 2010 Montrose Rotary Club is working to establish links between the school and Lawson Academy in Nyumbani, Kitui District

Kitui District was an administrative district in the Eastern Province of Kenya. Its capital was Kitui. The district had an area of 20,402 km2.

Kitui District was created in 1895 as one of the original districts of Ukamba Province among, Ulu (th ...

, Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

, a village created to accommodate HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

orphans and grandparents affected by a high incidence of AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

in the region.

Exchange programmes

Students studying German have the option of becoming part of an exchange with Icking Gymnasium inIcking

Icking is a municipality in the district of Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen in Bavaria in Germany.

People

* Anita Augspurg, lived in Icking from 1916 until she fled the Nazis

* Dieter Borsche, actor, lived in Icking in the beginning of the '60s.

* Be ...

, Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

. Since 2007 an exchange programme has been running between Montrose Academy and Forest Park High School in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, United States.

Activities

Student activities include the Baroque Ensemble, Book Group, Breakfast Club,cheerleading

Cheerleading is an activity in which the participants (called cheerleaders) cheer for their team as a form of encouragement. It can range from chanting slogans to intense Physical exercise, physical activity. It can be performed to motivate s ...

, Chess Club, Craft Club, Drama Club, Duke of Edinburgh Award

The Duke of Edinburgh's Award (commonly abbreviated DofE) is a youth awards programme founded in the United Kingdom in 1956 by the Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, which has since expanded to 144 nations. The awards recognise adolescents and ...

, Fairtrade Group, fantasy football, Green Group, Montrose Academy Musical Association, Montrose Academy Rock Challenge Team, Pottery, Samba Band, School Choir, Spanish Club, War Games Club, XL Club, Young Enterprise

Young Enterprise is a British charity that specialise in providing enterprise education and financial education to young people. Young Enterprise works directly with young people, teachers, volunteers, and influencers with aim of building a suc ...

and Zumba

Zumba is a fitness program that involves cardio and Latin-inspired dance. It was founded by Colombian dancer and choreographer Beto Pérez in 2001. It currently has 200,000 locations, with 15 million people taking classes weekly, and is locat ...

.

Montrose Academy has a debating society and has entered teams into the Scottish National Youth Parliament Competition. The school won the competition in 2005 and 2006. The English Department runs an annual debating

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse, discussion, and oral addresses on a particular topic or collection of topics, often with a moderator and an audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for opposing viewpoints. Historica ...

competition for pupils in the Junior School where the winning team is entered into The Courier and Chartered Institute of Bankers in Scotland Schools Junior Debating Competition. The school's debating society participated in the STV schools referendum debates 2014, placing 3rd overall.

There are small gymnasia inside the school and playing grounds outside. The facilities of the adjacent Sports Centre are used by the school for physical education classes. A new swimming pool is being built attached to the Sports Centre; work started in 2011 and the project will be completed by October 2012. During this time improvements are being made at Montrose Academy including the installation of a small gym, new flooring, changing rooms and showers to the cost of £140,000.

There are small gymnasia inside the school and playing grounds outside. The facilities of the adjacent Sports Centre are used by the school for physical education classes. A new swimming pool is being built attached to the Sports Centre; work started in 2011 and the project will be completed by October 2012. During this time improvements are being made at Montrose Academy including the installation of a small gym, new flooring, changing rooms and showers to the cost of £140,000.

Other activities

Pupils at Montrose Academy are involved in voting in the Rose Queen (and her attendants) who have been crowned at the annual Montrose Highland Games since 1968.Alumni

* the botanistRobert Brown Robert Brown may refer to: Robert Brown (born 1965), British Director, Animator and author

Entertainers and artists

* Washboard Sam or Robert Brown (1910–1966), American musician and singer

* Robert W. Brown (1917–2009), American printmaker ...

(1773–1858),

* politician Joseph Hume

Joseph Hume Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (22 January 1777 – 20 February 1855) was a Scottish surgeon and Radicals (UK), Radical Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), MP.Ronald K. Huch, Paul R. Ziegler 1985 Joseph Hume, the People's M.P ...

(1777–1855), and James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote '' The History of Britis ...

(1773–1836) historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

, economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

, political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be academics or independent scholars.

Ancient

* Aristotle

* Chanakya

* Cicero

* Confucius

* Mencius

* ...

, and philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

attended the school during the same period.

* Alexander Gibson (botanist)

Alexander Gibson (1800–1867) was a Scottish surgeon and botanist who worked in India.

He was born in Kincardineshire and studied at Edinburgh. He went to India as a surgeon in the Honourable East India Company. He became a superintendent of th ...

* the poet Alexander Smart (b.1798), satirised the teaching methods of James Norval at Montrose Academy in his poem, "Recollections of Auld Lang Syne".

* Edward Balfour

Edward Green Balfour (6 September 1813 – 8 December 1889) was a Scottish surgeon, orientalist and pioneering environmentalist in India. He founded museums at Madras and Bangalore, a zoological garden in Madras and was instrumental in raising ...

, (1813–1889) was a surgeon, orientalist and pioneering environmentalist. * Captain Sir Alexander Burnes

Captain Sir Alexander Burnes (16 May 1805 – 2 November 1841) was a Scottish explorer, military officer and diplomat associated with the Great Game. He was nicknamed Bokhara Burnes for his role in establishing contact with and expl ...

(1805–41), traveller and explorer also had connections with India

* A number of former pupils are connected with the Scottish Renaissance

The Scottish Renaissance (; ) was a mainly literary movement of the early to mid-20th century that can be seen as the Scottish version of modernism. It is sometimes referred to as the Scottish literary renaissance, although its influence went be ...

cultural movement of the early twentieth century. This includes the writers John Angus (1906–1968), Fionn MacColla

Fionn Mac Colla (born Thomas Douglas MacDonald; 4 March 1906 – 20 July 1975) was a Scottish novelist closely connected to the Scottish Gaelic language and culture who campaigned for it to return to what he perceived to be its rightful place i ...

and Willa Muir

Willa Muir (née Anderson; 13 March 1890 – 22 May 1970), also known as Agnes Neill Scott, was a Scottish novelist, essayist and translator.Beth Dickson, '' British women writers : a critical reference guide'' edited by Janet Todd. New York : ...

(1890–1970) (wife of Edwin Muir

Edwin Muir CBE (15 May 1887 – 3 January 1959) was a Scottish poet, novelist and translator. Born on a farm in Deerness, a parish of Orkney, Scotland, he is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry written in plain language and wit ...

);

* Sir James Davidson Stuart Cameron FRSE

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and Literature, letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". ...

(1900-1969), Director of Post Graduate Medicine, Dacca

* the poets Helen Cruickshank

Helen Burness Cruickshank (15 May 1886 – 2 March 1975) was a Scottish poet and suffragette and a focal point of the Scottish Renaissance. Scottish writers associated with the movement met at her home in Corstorphine.

Early life and educ ...

(1886–1975) and Hugh MacDiarmid

Christopher Murray Grieve (11 August 1892 – 9 September 1978), best known by his pen name Hugh MacDiarmid ( , ), was a Scottish poet, journalist, essayist and political figure. He is considered one of the principal forces behind the Scottish ...

(1892–1978)

* the artists Edward Baird (1904–49) and William Lamb (1893–1951).

* William Allen Neilson (1869–1946), writer and Professor of English.;

* Prof James Simpson Silver CBE (1913–1997), former James Watt Chair of Mechanical Engineering from 1967 to 1979 at the University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow (abbreviated as ''Glas.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals; ) is a Public university, public research university in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded by papal bull in , it is the List of oldest universities in continuous ...

; and Professor of Mechanical Engineering from 1962 to 1966 at Heriot-Watt University

Heriot-Watt University () is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1821 as the School of Arts of Edinburgh, the world's first mechanics' institute, and was subsequently granted university status by roya ...

* Prof Arthur James Beattie FRSE

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and Literature, letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". ...

(1914–1996), Professor of Greek from 1951 to 1981 at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

, and fellow and lecturer in Greek and Classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

at Sidney Sussex College

Sidney Sussex College (historically known as "Sussex College" and today referred to informally as "Sidney") is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England. The College was founded in 1 ...

, University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

(1946–51);

* Robert Cormack (1946-), Professor of Sociology and Pro-Vice-Chancellor (1996–2001) of the Queen's University of Belfast.

* gynaecologist John Chassar Moir CBE (1900–1977), Nuffield Professor of Obstetrics and Gynæcology from 1937 to 1967 at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, and who led research in the 1930s which resulted in the discovery of ergometrine

Ergonovine, also known as ergometrine and lysergic acid propanolamide, is a medication used to cause contractions of the uterus to treat heavy vaginal bleeding after childbirth. It can be used either by mouth, by injection into a muscle, or ...

.

* electrical engineer James Blyth (1838–1906), was an early pioneer of wind power who built the world's first wind turbine that generated electricity in 1887, although lacked a control mechanism (later developed by the American Charles F. Brush

Charles Francis Brush (March 17, 1849June 15, 1929) was an American engineer, inventor, entrepreneur, and philanthropist.

Biography

Brush was born in Euclid Township, Ohio, to Isaac Elbert Brush and Delia Williams Phillips. Isaac Brush was a d ...

)

* Major General George Alexander Renny (1825–1887) received the Victoria Cross.

* accountant William Barclay Peat

Sir William Barclay Peat (15 February 1852 – 24 January 1936) was an accountant and one of the founders of KPMG.

Career

Peat born in Forebank, St Cyrus, Kincardine, Fife, Kincardine, Scotland. He was the second son of James Peat and Marg ...

(1852–1936) studied law at Montrose Academy, whose firm founded in 1870 became Peat Marwick, and later the worldwide firm KPMG

KPMG is a multinational professional services network, based in London, United Kingdom. As one of the Big Four accounting firms, along with Ernst & Young (EY), Deloitte, and PwC. KPMG is a network of firms in 145 countries with 275,288 emplo ...

in 1987 when it merged with the Dutch firm KMG

* footballer Gordon Smith (1924–2004) who played for Hibernian F.C.

Hibernian Football Club (), commonly known as Hibs, is a professional football club in Edinburgh, Scotland. The team competes in the , the top division of Scottish football. The club was founded in 1875 by members of Edinburgh's Irish commu ...

* Sir Alan Rothnie CMG, Ambassador to Saudi Arabia from 1972 to 1976, and to Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

from 1976 to 1980

See also

*List of the oldest schools in the United Kingdom

This list of the oldest schools in the United Kingdom contains extant schools in the United Kingdom established prior to 1800. The dates refer to the foundation or the earliest documented contemporary reference to the school. In many cases the date ...

References

Further reading

* Anderson, R. D., "Secondary Schools and Scottish Society in the Nineteenth Century", '' Past & Present'', No.109 (Nov. 1985), pp. 176–203 * Anderson, R. D., ''Education and the Scottish People, 1750-1918'', (Oxford University Press, 1995) * Clarke, M. L., ''Classical Education in Britain 1500-1900'', (Cambridge University Press, 1959) * Cumming, Ian, "The Scottish Education of James Mill", ''History of Education Quarterly'', Vol.2, No.3 (Sept. 1962), pp. 152–167 * Jessop, J. C., ''Education in Angus'', (University of London Press, 1931) * Rait, Robert S., "Andrew Melville and the Revolt against Aristotle in Scotland", ''The English Historical Review

''The English Historical Review'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed academic journal that was established in 1886 and published by Oxford University Press (formerly by Longman). It publishes articles on all aspects of history – British, European, a ...

'', Vol.14, No.54 (Apr. 1899), pp. 250–260

* Strong, John, "The Development of Secondary Education in Scotland", ''The School Review'', Vol. 15, No. 8 (Oct. 1907), pp. 594–607

* Strong, John, ''A History of Secondary Education in Scotland: An Account of Scottish Secondary Education from Early Times to the Education Act of 1908'', (The Clarendon Press, 1909)

External links

School website

(Angus Council)

Angus Secondary School Attainment levels 2007-2009

(Angus Council) {{authority control Educational institutions established in 1815 Category B listed buildings in Angus, Scotland Secondary schools in Angus, Scotland 1815 establishments in Scotland History of Angus, Scotland Neoclassical architecture in Scotland Montrose, Angus