Monarchism In Iraq on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of

monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

. Conversely, the opposition to monarchical rule is referred to as republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

.

Depending on the country, a royalist may advocate for the rule of the person who sits on the throne, a regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

, a pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term may often be used to either refer to a descendant of a deposed monarchy or a claim that is not legitimat ...

, or someone who would otherwise occupy the throne but has been deposed.

History

Monarchical rule is among the oldest political institutions. The similar form of societal hierarchy known aschiefdom

A chiefdom is a political organization of people representation (politics), represented or government, governed by a tribal chief, chief. Chiefdoms have been discussed, depending on their scope, as a stateless society, stateless, state (polity) ...

or tribal kingship is prehistoric. Chiefdoms provided the concept of state formation, which started with civilizations such as Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

and the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE ...

. In some parts of the world, chiefdoms became monarchies.

Monarchs have generally ceded power in the modern era, having substantially diminished since World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. This process can be traced back to the 18th century, when Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

and others encouraged "enlightened absolutism

Enlightened absolutism, also called enlightened despotism, refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhanc ...

", which was embraced by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II and by Catherine II of Russia

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

.

In the 17th and 18th centuries the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

began. This resulted in new anti-monarchist ideas which resulted in several revolutions such as the 18th century American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and the French Revolution which were both additional steps in the weakening of power of European monarchies. Each in its different way exemplified the concept of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

upheld by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

. 1848 ushered in a wave of revolutions against the continental European monarchies. World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and its aftermath saw the end of three major European monarchies: the Russian Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transliterated as Romanoff; , ) was the reigning dynasty, imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after Anastasia Romanovna married Ivan the Terrible, the first crowned tsar of all Russi ...

dynasty, the German Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, ; , ; ) is a formerly royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) German dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenburg, Prussia, the German Empire, and Romania. ...

dynasty, including all other German monarchies, and the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

dynasty.

With the arrival of communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

by the end of 1947, the remaining Eastern European monarchies, namely the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania () was a constitutional monarchy that existed from with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King of Romania, King Carol I of Romania, Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian royal family), until 1947 wit ...

, the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

, the Kingdom of Albania, the Kingdom of Bulgaria

The Tsardom of Bulgaria (), also known as the Third Bulgarian Tsardom (), usually known in English as the Kingdom of Bulgaria, or simply Bulgaria, was a constitutional monarchy in Southeastern Europe, which was established on , when the Bulgaria ...

, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

, were all abolished and replaced by socialist republics.

Africa

Central Africa

In 1966, theCentral African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

was overthrown at the hands of Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa (; 22 February 1921 – 3 November 1996) was a Central African politician and military officer who served as the second president of the Central African Republic (CAR), after seizing power in the Saint-Sylvestre coup d ...

during the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état Saint-Sylvestre may refer to:

* Saint-Sylvestre, Quebec

* Saint-Sylvestre, Ardèche, France

* Saint-Sylvestre, Haute-Savoie, France

* Saint-Sylvestre, Haute-Vienne, France

See also

* Pope Sylvester I, honored in the Catholic Church and the Eas ...

. He established the Central African Empire

The Central African Empire () was established on 4 December 1976 when the then-President of the Central African Republic, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, declared himself Emperor of Central Africa. The empire would fall less than three years later when ...

in 1976 and ruled as Emperor Bokassa I until 1979, when he was subsequently deposed during Operation Caban

Operation Caban was a bloodless military operation by the France, French intelligence service Service de documentation extérieure et de contre-espionnage, SDECE in September 1979 to depose Emperor of Central Africa, Emperor Jean-Bédel Bokassa, ...

and Central Africa returned to republican rule.

Ethiopia

In 1974, one of the world's oldest monarchies was abolished inEthiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

with the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I (born Tafari Makonnen or ''Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles#Lij, Lij'' Tafari; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as the Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, Rege ...

.

Asia

China

For most of its history, China was organized into various dynastic states under the rule of hereditary monarchs. Beginning with the establishment of dynastic rule byYu the Great

Yu the Great or Yu the Engineer was a legendary king in ancient China who was credited with "the first successful state efforts at flood control", his establishment of the Xia dynasty, which inaugurated Dynasties in Chinese history, dynastic ru ...

, and ending with the abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the Order of succession, succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of ...

of the Xuantong Emperor

Puyi (7 February 190617 October 1967) was the final emperor of China, reigning as the eleventh monarch of the Qing dynasty from 1908 to 1912. When the Guangxu Emperor died without an heir, Empress Dowager Cixi picked his nephew Puyi, aged tw ...

in AD 1912, Chinese historiography

Chinese historiography is the study of the techniques and sources used by historians to develop the recorded history of China.

Overview of Chinese history

The recording of events in Chinese history dates back to the Shang dynasty ( 1600–1046 ...

came to organize itself around the succession of monarchical dynasties. Besides those established by the dominant Han ethnic group or its spiritual Huaxia

''Huaxia'' is a historical concept representing the Chinese nation, and came from the self-awareness of a common cultural ancestry by ancestral populations of the Han people.

Etymology

The earliest extant authentic attestation of the ''H ...

predecessors, dynasties throughout Chinese history were also founded by non-Han peoples.

India

In India, monarchies recorded history of thousands of years before the country was declared a republic in 1950. KingGeorge VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

had previously been the last Emperor of India

Emperor (or Empress) of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948 Royal Proclamation of 22 June 1948, made in accordance with thIndian Independence Act 1947, 10 & 11 GEO. 6. CH ...

until August 1947, when the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

dissolved. Karan Singh

Karan Singh (born 9 March 1931) is an Indian politician and philosopher. He is the titular Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. From 1952 to 1965 he was the '' Sadr-i-Riyasat'' (President) of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. ...

served as the last prince regent of Jammu and Kashmir

Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory since 2019

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered by India as a state from 1952 to 2019

* Jammu and Kashmir (prin ...

until November 1952.

Japan

The emperor of Japan or , literally " ruler from heaven" or "heavenly sovereign

The Heavenly Sovereign () was the first legendary Chinese king after Pangu's era. According to ''Yiwen Leiju'', he was the first of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, Three Sovereigns.

Name

The book ''Lushi (book), Lushi'' from the Song D ...

", is the hereditary monarch

A hereditary monarchy is a form of government and succession of power in which the throne passes from one member of a ruling family to another member of the same family. A series of rulers from the same family would constitute a dynasty. It is his ...

and head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

of he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. The Imperial Household Law

is a Japanese law that governs the line of imperial succession, the membership of the imperial family, and several other matters pertaining to the administration of the Imperial Household.

In 2017, the National Diet changed the law to enable ...

governs the line of imperial succession. The emperor is personally immune

In biology, immunity is the state of being insusceptible or resistant to a noxious agent or process, especially a pathogen or infectious disease. Immunity may occur naturally or be produced by prior exposure or immunization.

Innate and adaptive ...

from prosecution and is also recognized as the head of the Shinto

, also called Shintoism, is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religions, East Asian religion by Religious studies, scholars of religion, it is often regarded by its practitioners as Japan's indigenous religion and as ...

religion, which holds the emperor to be the direct descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu

, often called Amaterasu () for short, also known as and , is the goddess of the sun in Japanese mythology. Often considered the chief deity (''kami'') of the Shinto pantheon, she is also portrayed in Japan's earliest literary texts, the () ...

. According to tradition, the office of emperor was created in the 7th century BC, but modern scholars believe that the first emperors did not appear until the 5th or 6th centuries AD.Hoye, Timothy. (1999). ''Japanese Politics: Fixed and Floating Worlds,'' p. 78; "According to legend, the first Japanese emperor was Jinmu. Along with the next 13 emperors, Jimmu

was the legendary first emperor of Japan according to the and . His ascension is traditionally dated as 660 BC.Kelly, Charles F"Kofun Culture"Kinmei." During the

"''Kamakura-jidai''"

in ''Japan Encyclopedia'', p. 459. In 1867, shogun

/ref>

Kamakura period

The is a period of History of Japan, Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura, Kanagawa, Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the G ...

from 1185 to 1333, the '' shōguns'' were the ''de facto'' rulers of Japan, with the emperor and the imperial court acting as figurehead

In politics, a figurehead is a practice of who ''de jure'' (in name or by law) appears to hold an important and often supremely powerful title or office, yet '' de facto'' (in reality) exercises little to no actual power. This usually means that ...

s. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Kamakura-jidai''"

in ''Japan Encyclopedia'', p. 459. In 1867, shogun

Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Kazoku, Prince was the 15th and last ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He was part of a movement which aimed to reform the aging shogunate, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He resigned his position as shogun in late 1867, while ai ...

stepped down, restoring Emperor Meiji

, posthumously honored as , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the List of emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession, reigning from 1867 until his death in 1912. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ...

to power. The Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan ( Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in ...

was adopted In 1889, after which the emperor became an active ruler with considerable political power that was shared with the Imperial Diet. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the 1947 Constitution of Japan was enacted, defining the emperor as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people. The emperor has exercised a purely ceremonial role ever since.

Europe

Albania

The last separate monarchy to take root in Europe,Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

began its recognised modern existence as a principality

A principality (or sometimes princedom) is a type of monarchy, monarchical state or feudalism, feudal territory ruled by a prince or princess. It can be either a sovereign state or a constituent part of a larger political entity. The term "prin ...

(1914) and became a kingdom after a republican interlude in 1925–1928. Since 1945 the country has operated as an independent republic. The Albanian Democratic Monarchist Movement Party (founded in 2004) and the Legality Movement Party

The Legality Movement Party (, abbr. PLL) is a monarchist political party in Albania led by Shpetim Axhami. It supports the restoration of the Albanian monarchy under the House of Zogu, with the house's current head Prince Leka crowned as kin ...

(founded in 1924) advocate restoration of the House of Zogu

The House of Zogu, or Zogolli during Ottoman Albania, Ottoman times and until 1922, is an Albanian people, Albanian dynastic family whose roots date back to the early 20th century. The family provided the first president and the short-lived modern ...

as monarchs—the concept has gained little electoral support.

Austria-Hungary

Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary, theRepublic of German-Austria

The Republic of German-Austria (, alternatively spelt ), commonly known as German-Austria (), was an unrecognised state that was created following World War I as an initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking and ethn ...

was proclaimed. The Constitutional Assembly of German Austria passed the Habsburg Law

The Habsburg Law (''Habsburgergesetz'' (in full, the Law concerning the Expulsion and the Takeover of the Assets of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine) ''Gesetz vom 3. April 1919 betreffend die Landesverweisung und die Übernahme des Vermögens des ...

, which permanently exiled the Habsburg family from Austria. Despite this, significant support for the Habsburg family persisted in Austria. Following the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, ), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "German Question, Greater Germany") arose after t ...

of 1938, the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

government suppressed monarchist activities. By the time Nazi rule ended in Austria, support for monarchism had largely evaporated.

In Hungary, the rise of the Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Hungarian Soviet Republic, also known as the Socialist Federative Soviet Republic of Hungary was a short-lived communist state that existed from 21 March 1919 to 1 August 1919 (133 days), succeeding the First Hungarian Republic. The Hungari ...

in 1919 provoked an increase in support for monarchism; however, efforts by Hungarian monarchists failed to bring back a royal head of state, and the monarchists settled for a regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

, Admiral Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya (18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957) was a Hungarian admiral and statesman who was the Regent of Hungary, regent of the Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946), Kingdom of Hungary Hungary between the World Wars, during the ...

, to represent the monarchy until the throne could be re-occupied. Horthy ruled as regent from 1920 to 1944. During his regency, attempts were made by Karl von Habsburg

Karl von Habsburg (given names: ''Karl Thomas Robert Maria Franziskus Georg Bahnam''; born 11 January 1961) is an Austrian politician and the head of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, the former royal house of the defunct Austro-Hungarian thrones ...

() to return to the Hungarian throne, which ultimately failed. Following Karl's death in 1922, his claim to the Kingdom of Hungary was inherited by Otto von Habsburg

Otto von Habsburg (, ; 20 November 1912 4 July 2011) was the last crown prince of Austria-Hungary from 1916 until the dissolution of the empire in November 1918. In 1922, he became the pretender to the former thrones, head of the House of Habs ...

(1912–2011), although no further attempts were made to take the Hungarian throne.

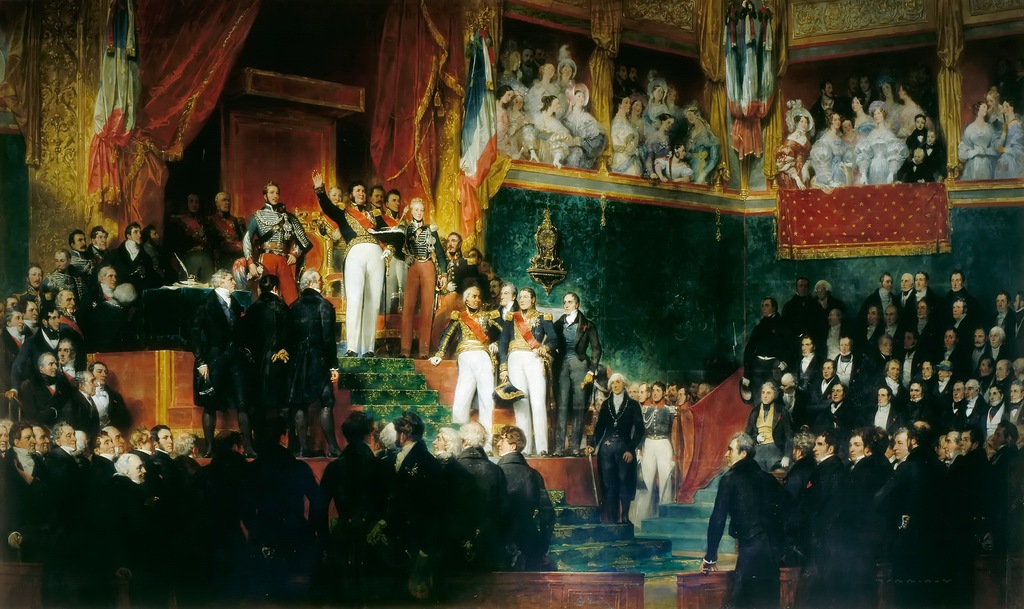

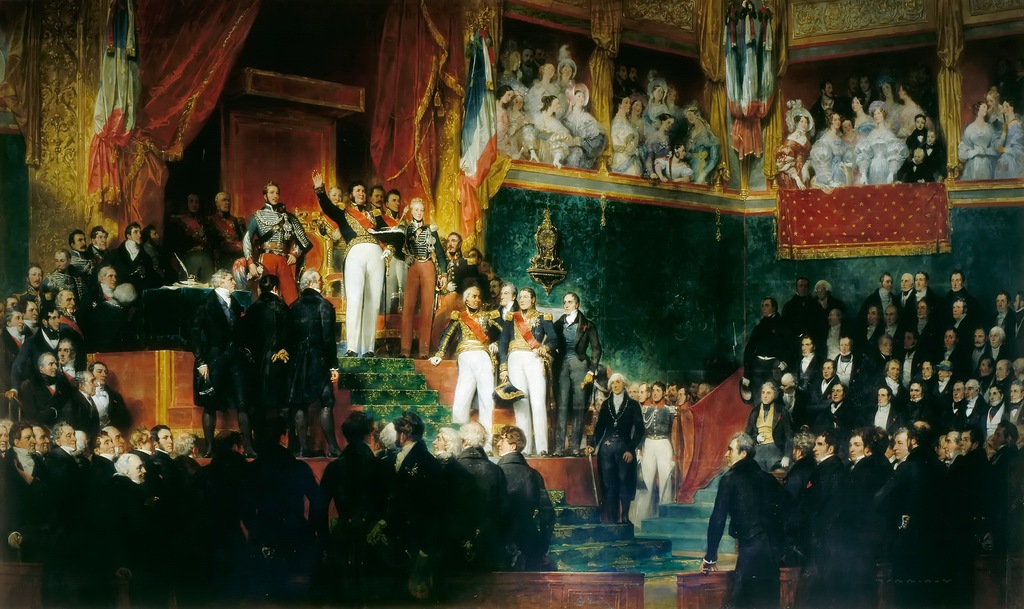

France

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

was ruled by monarch

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest ...

s from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the government of France from 1852 to 1870. It was established on 2 December 1852 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of France under the French Second Republic, who proclaimed hi ...

in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

usually regards Clovis I

Clovis (; reconstructed Old Frankish, Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first List of Frankish kings, king of the Franks to unite all of the Franks under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a ...

, King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dux, dukes and monarch, reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Franks, Salian Mero ...

(), as the first king of France. However, historians today consider that such a kingdom did not begin until the establishment of West Francia

In medieval historiography, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () constitutes the initial stage of the Kingdom of France and extends from the year 843, from the Treaty of Verdun, to 987, the beginning of the Capet ...

, during the dissolution of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Franks, Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as List of Frankish kings, kings of the Franks since ...

in the 800s.

Germany

In 1920s Germany, a number of monarchists gathered around theGerman National People's Party

The German National People's Party (, DNVP) was a national-conservative and German monarchy, monarchist political party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major nationalist party in Weimar German ...

(founded in 1918), which demanded the return of the Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, ; , ; ) is a formerly royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) German dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenburg, Prussia, the German Empire, and Romania. ...

monarchy and an end to the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

; the party retained a large base of support until the rise of Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

in the 1930s, as Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

staunchly opposed monarchism.

Italy

The aftermath ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

saw the return of monarchist/republican rivalry in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, where a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

was held on whether the state should remain a monarchy or become a republic. The republican side won the vote by a narrow margin, and the modern Republic of Italy was created.Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 134 del 20 giugno 1946/ref>

Liechtenstein

There have been 16 monarchs of thePrincipality of Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (, ; ; ), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein ( ), is a doubly landlocked German-speaking microstate in the Central European Alps, between Austria in the east and north and Switzerland in the west and south. Liechtenst ...

since 1608. The current Prince of Liechtenstein, Hans-Adam II

Hans-Adam II (Johannes Adam Ferdinand Alois Josef Maria Marco d'Aviano Pius; born 14 February 1945) is the Prince of Liechtenstein, reigning since 1989. He is the son of Prince Franz Joseph II and his wife, Countess Georgina von Wilczek. He al ...

, has reigned since 1989. In 2003, during a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

, 64.3% of the population voted to increase the power of the prince.

Norway

The position ofKing of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty king ...

has existed continuously since the unification of Norway

The Unification of Norway ( Norwegian Bokmål: ''Rikssamlingen'') is the process by which Norway merged from several petty kingdoms into a single kingdom, predecessor to the modern Kingdom of Norway.

History

King Harald Fairhair is the mo ...

in 872. Following the dissolution of union with Sweden and the abdication of King Oscar II

Oscar II (Oscar Fredrik; 21 January 1829 – 8 December 1907) was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death in 1907 and King of Norway from 1872 to 1905.

Oscar was the son of King Oscar I and Queen Josephine. He inherited the Swedish and Norweg ...

of Sweden as King of Norway, the 1905 Norwegian monarchy referendum

A referendum on retaining the monarchy or becoming a republic was held in Norway on 12 and 13 November 1905.Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1437 Voters were asked whether they approved of the Stor ...

saw 78.94% of Norway's voters approving the government's proposition to invite Prince Carl of Denmark to become their new king. Following the vote, the prince then accepted the offer, becoming King Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was King of Norway from 18 November 1905 until his death in 1957.

The future Haakon VII was born in Copenhagen as Prince Carl of Denmark. He was the second son of the Crown Prince and Crown Princess ...

.

In 2022, the Norwegian parliament held a vote on abolishing the monarchy and replacing it with a republic. The proposal failed, with a 134–35 result in favor of retaining the monarchy. The idea was highly controversial in Norway, as the vote was spearheaded by the sitting Minister of Culture and Equality, who had sworn an oath of loyalty to King Harald V of Norway

Harald V (, ; born 21 February 1937) has been King of Norway since 1991.

A member of the House of Glücksburg, Harald was the third child and only son of King Olav V of Norway and Princess Märtha of Sweden. He was second in the Succession to t ...

the previous year. Additionally, when polls were conducted, it was found that 84% of the Norwegian public supported the monarchy, with only 16% unsure or against the monarchy.

Russia

Monarchy in theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

collapsed in March 1917, following the abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the Order of succession, succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of ...

of Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. He married ...

. Parts of the White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

, and in particular émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social exile or self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French verb ''émigrer'' meaning "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Hugueno ...

s and their (founded in 1921 and now based in Canada) continued to advocate for monarchy as "the sole path to the rebirth of Russia". In the modern era, a minority of Russians, including Vladimir Zhirinovsky

Vladimir Volfovich Zhirinovsky (, , né Eidelstein, ; 25 April 1946 – 6 April 2022) was a Russian right-wing populist politician and the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) from its creation in 1992 until his death in 20 ...

(1946–2022), have openly advocated for a restoration of the Russian monarchy

A restoration of the Russian monarchy is a hypothetical event in which the Russian monarchy, which has been non-existent since the abdication of Nicholas II on 15 March 1917 and the execution of him and the rest of his closest family in 1918, is ...

. Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna is widely considered the valid heir to the throne, in the event that a restoration occurs. Other pretenders and their supporters dispute her claim.

Spain

In 1868, QueenIsabella II of Spain

Isabella II (, María Isabel Luisa de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904) was Queen of Spain from 1833 until her deposition in 1868. She is the only queen regnant in the history of unified Spain.

Isabella wa ...

was deposed during the Spanish Glorious Revolution. The Duke of Aosta

Duke of Aosta (; ) was a title in the Italian nobility. It was established in the 13th century when Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, made the County of Aosta a duchy. The region was part of the Savoyard state and the title was granted to variou ...

, an Italian prince, was invited to rule and replace Isabella. He did so for a three-year period, reigning as Amadeo I before abdicating in 1873, resulting in the establishment of the First Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), historiographically referred to as the First Spanish Republic (), was the political regime that existed in Spain from 11 February 1873 to 29 December 1874.

The Republic's founding ensued after the abdication of King ...

. The republic lasted less than two years, and was overthrown during a coup by General Arsenio Martínez Campos

Arsenio Martínez-Campos y Antón, born Martínez y Campos (14 December 1831 – 23 September 1900), was a Spanish officer who rose against the First Spanish Republic in a military revolution in 1874 and restored Spain's Bourbon dynasty. Later, ...

. Campos restored the Bourbon monarchy

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. A br ...

under Isabella II's more popular son, Alfonso XII

Alfonso XII (Alfonso Francisco de Asís Fernando Pío Juan María de la Concepción Gregorio Pelayo de Borbón y Borbón; 28 November 185725 November 1885), also known as ''El Pacificador'' (Spanish: the Peacemaker), was King of Spain from 29 D ...

.

After the 1931 Spanish local elections

The 1931 Spanish local elections were held on 12 April throughout all Municipalities of Spain, municipalities in Spain to elect 80,472 councillors.

The elections were perceived as a plebiscite on the Monarchy of Spain, monarchy of Alphonse XIII of ...

, King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Alfonso León Fernando María Jaime Isidro Pascual Antonio de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena''; French language, French: ''Alphonse Léon Ferdinand Marie Jacques Isidore Pascal Antoine de Bourbon''; 17 May ...

voluntarily left Spain and republicans proclaimed a Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII. ...

.

After the assassination of opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo

José Calvo Sotelo, 1st Duke of Calvo Sotelo, GE (6 May 1893 – 13 July 1936) was a Spanish jurist and politician. He was the minister of finance during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera and a leading figure during the Spanish Second ...

in 1936, right-wing forces banded together to overthrow the Republic. During the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

of 1936 to 1939, General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

established the basis for the Spanish State

Francoist Spain (), also known as the Francoist dictatorship (), or Nationalist Spain () was the period of Spanish history between 1936 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death i ...

(1939–1975). In 1938, the autocratic government of Franco claimed to have reconstituted the Spanish monarchy ''in absentia'' (and in this case ultimately yielded to a restoration, in the person of King Juan Carlos

Juan Carlos I (; Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 November 1975 until his abdication on 19 June 2014. In Sp ...

).

In 1975, Juan Carlos I

Juan Carlos I (; Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 November 1975 until Abdication of Juan Carlos I, his abdic ...

became King of Spain and began the Spanish transition to democracy

The Spanish transition to democracy, known in Spain as (; ) or (), is a period of History of Spain, modern Spanish history encompassing the regime change that moved from the Francoist dictatorship to the consolidation of a parliamentary system ...

. He abdicated in 2014, and was succeeded by his son Felipe VI

Felipe VI (; Felipe Juan Pablo Alfonso de Todos los Santos de Borbón y Grecia; born 30 January 1968) is King of Spain. In accordance with the Spanish Constitution, as monarch, he is head of state and commander-in-chief of the Spanish Armed For ...

.

United Kingdom

In England, royalty ceded power to other groups in a gradual process. In 1215, a group of nobles forced King John to signMagna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

, which guaranteed the English barons certain liberties and established that the king's powers were not absolute. King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

was executed in 1649, and the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

was established as a republic. Highly unpopular, the republic was ended in 1660, and the monarchy was restored under King Charles II. In 1687–88, the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

and the overthrow of King James II established the principles of constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

, which would later be worked out by Locke and other thinkers. However, absolute monarchy, justified by Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered to be one of the founders ...

in ''Leviathan

Leviathan ( ; ; ) is a sea serpent demon noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, and the pseudepigraphical Book of Enoch. Leviathan is of ...

'' (1651), remained a prominent principle elsewhere.

Following the Glorious Revolution, William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily ()

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg (1817–1890)

N ...

and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 1662 – 28 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland with her husband, King William III and II, from 1689 until her death in 1694. Sh ...

were established as constitutional monarchs, with less power than their predecessor James II. Since then, royal power has become more ceremonial, with powers such as refusal to assent last exercised in 1708 by Queen Anne. Once part of the United Kingdom (1801–1922), southern Ireland rejected monarchy and became the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

in 1949. Support for a ceremonial monarchy remains high in Britain: Queen Elizabeth II (), possessed wide support from the U.K.'s population.

Vatican City State

The Vatican City State is considered to be Europe's last absolute monarchy. The microstate is headed by the Pope, who doubles as its monarch according to the Vatican constitution. The nation was formed under Pope Pius XI in 1929, following the signing of the Lateran Treaty. It was the successor state to the Papal States, which collapsed under Pope Pius IX in 1870. Pope Leo XIV (in office from 2025) serves as the nation's absolute monarch.North America

Canada

Canada possesses one of the world's oldest continuous monarchies, having been established in the 16th century. Queen Elizabeth II had served as its sovereign since her ascension to the throne in 1952 until her death in 2022. Her son, King Charles III, now sits on the throne.Costa Rica

The struggle between monarchists and republicans led to the Costa Rican civil war of 1823. Costa Rican monarchists include Joaquín de Oreamuno y Muñoz de la Trinidad, José Santos Lombardo y Alvarado and José Rafael Gallegos Alvarado. Costa Rica stands out for being one of the few countries with foreign monarchism, that is, where the monarchists did not intend to establish an indigenous monarchy. Costa Rican monarchists were loyal to Emperor Agustín de Iturbide of the First Mexican Empire.Honduras

After the independence of the Captaincy General of Guatemala, general captaincy of Guatemala from the Spanish Empire, Spanish empire, she joined the First Mexican Empire for a brief period, this unleashed the division of the Honduran elites. These were divided between the annexationists, made up mostly of illustrious Spanish-descendant families and members of the conservative party who supported the idea of being part of an empire, and the liberals who wanted Central America to be a separate nation under a republican system. The greatest example of this separation was in the two most important cities of the province, on the one hand Comayagua, which firmly supported the legitimacy of Iturbide I as emperor and remained a pro-monarchist bastion in Honduras, and on the other hand Tegucigalpa who supported the idea of forming a federation of Central American states under a republican system.

Mexico

After obtaining independence from Spain, the First Mexican Empire was established under Emperor Agustín de Iturbide, Agustín I. His reign lasted less than one year, and he was forcefully deposed. In 1864, the Second Mexican Empire was formed under Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, Maximilian I. Maximilian's government enjoyed French aid, but opposition from America, and collapsed after three years. Much like Agustín I, Maximilian I was deposed and later executed by his republican enemies. Since 1867, Mexico has not possessed a monarchy. Today, some Mexican monarchist organizations advocate for Maximilian von Götzen-Iturbide or Carlos Felipe de Habsburgo to be instated as the Emperor of Mexico.Nicaragua

The Miskito people, miskito ethnic group inhabits part of the Atlantic coast of Honduras and Nicaragua, by the beginning of the 17th century the said ethnic group was reorganized under a single chief known as Ta Uplika, for the reign of his grandson King Oldman (king), Oldman I this group had a very close relationship With the English, they managed to turn the Mosquitia coast into an English protectorate that would decline in the 19th century until it completely disappeared in 1894 with the abdication of Robert Henry Clarence, Robert II. Currently, the Miskitos who are shot between the two countries have denounced the neglect of their communities and abuses committed by the authorities. As a result of this, in Nicaragua several Miskito people began a movement of separatism from present-day Nicaragua and a re-institution of the monarchy.United States

English settlers first established the colony of Jamestown, Virginia, Jamestown in 1607, taking its name after King James VI and I. For 169 years, the Thirteen Colonies were ruled by the authority of the British crown. The Thirteen American Colonies possessed a total of 10 monarchs, ending with George III. During the American Revolutionary War, the colonies declared independence from Britain in 1776. Despite erroneous popular belief, the Revolutionary war was in fact fought over independence, not anti-monarchism as is commonly believed. In fact, many American colonists who fought in the war against George III were monarchists themselves, who opposed George, but desired to possess a different king. Additionally, the American colonists received the financial support of Louis XVI and Charles III of Spain during the war. After the U.S. declared its independence, the form of government by which it would operate still remained unsettled. At least two of America's Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton and Nathaniel Gorham, believed that America should be an independent monarchy. Various proposals to create an American monarchy were considered, including the Prussian scheme which would have made Prince Henry of Prussia (1726–1802), Prince Henry of Prussia king of the United States. Hamilton proposed that the leader of America should be an elected monarch, while Gorham pushed for a hereditary monarchy. U.S. military officer Lewis Nicola also desired for America to be a monarchy, suggesting George Washington accept the crown of America, which he declined. All attempts ultimately failed, and America was founded a Republic. During the American Civil War, a return to monarchy was considered as a way to solve the crisis, though it never came to fruition. Since then, the idea has possessed low support, but has been advocated by some public figures such as Ralph Adams Cram, Solange Hertz, Leland B. Yeager, Michael Auslin, Charles A. Coulombe, and Curtis Yarvin.South America

Brazil

From gaining its independence in 1822 until 1889, Brazil was governed as a constitutional monarchy with a branch of the House of Braganza, Portuguese Royal Family serving as monarchs. Prior to this period, Brazil had been a royal colony which had also served briefly as the seat of government for the Portuguese Empire following the occupation of that country by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1808. The history of the Empire of Brazil was marked by brief periods of political instability, several wars that Brazil won, and a marked increase in immigration which saw the arrival of both Jews and Protestants who were attracted by Brazil's reputation for religious tolerance. The final decades of the Empire under the reign of Pedro II of Brazil, Pedro II saw a remarkable period of relative peace both at home and internationally, coupled with dramatic economic expansion, the extension of basic civil rights to most people and the gradual restriction of Slavery in Brazil, slavery, culminating in its final abolition in 1888. It is also remembered for its thriving culture and arts. However, Pedro II had little interest in preserving the monarchy and passively accepted its overthrow by a military coup d'état in 1889 resulting in the establishment of a dictatorship known as the First Brazilian Republic.Current monarchies

The majority of current monarchies are constitutional monarchy, constitutional monarchies. In a constitutional monarchy the power of the monarch is restricted by either a written or unwritten constitution, this should not be confused with a ceremonial monarchy, in which the monarch holds only symbolic power and plays very little to no part in government or politics. In some constitutional monarchies the monarch does play a more active role in political affairs than in others. In Thailand, for instance, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who reigned from 1946 to 2016, played a critical role in the nation's political agenda and in various military coups. Similarly, in Morocco, King Mohammed VI of Morocco, Mohammed VI wields significant, but not absolute power. Liechtenstein is a democratic principality whose citizens have voluntarily given more power to their monarch in recent years. There remain a handful of countries in which the monarchy is an absolute monarch, absolute monarchy. The majority of these countries are oil-producing Arab Islamic monarchy, Islamic monarchies like Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. Other strong monarchies include Brunei and Eswatini.Political philosophy

Absolute monarchy stands as an opposition to History of Anarchism, anarchism and, additionally since the Age of Enlightenment; liberalism, capitalism,communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and socialism.

Otto von Habsburg

Otto von Habsburg (, ; 20 November 1912 4 July 2011) was the last crown prince of Austria-Hungary from 1916 until the dissolution of the empire in November 1918. In 1922, he became the pretender to the former thrones, head of the House of Habs ...

advocated a form of constitutional monarchy based on the primacy of the supreme judicial function, with hereditary succession, mediation by a tribunal is warranted if suitability is problematic.

Non-partisanship

British political scientist Vernon Bogdanor justifies monarchy on the grounds that it provides for a nonpartisanhead of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

, separate from the head of government, and thus ensures that the highest representative of the country, at home and internationally, does not represent a particular political party, but all people. Bogdanor also notes that monarchies can play a helpful unifying role in a multinational state, noting that "In Belgium, it is sometimes said that the king is the only Belgian, everyone else being either Flemish people, Fleming or Walloons, Walloon" and that the British sovereign can belong to all of the United Kingdom's Countries of the United Kingdom, constituent countries (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland), without belonging to any particular one of them.

he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...Private interest

Thomas Hobbes wrote that the private interest of the monarchy is the same with the public. The riches, power, and humour of a monarch arise only from the riches, strength, and reputation of his subjects. An elected Head of State is incentivised to increase his own wealth for leaving office after a few years whereas a monarch has no reason to corrupt because he would be cheating himself.Wise counsel

Thomas Hobbes wrote that a monarch can receive wise counsel with secrecy while an assembly cannot. Advisors to the assembly tend to be well-versed more in the acquisition of their own wealth than of knowledge; are likely to give their advices in long discourses which often excite men into action but do not govern them in it, moved by the flame of passion instead of enlightenment. Their multitude is a weakness.Long termism

Thomas Hobbes wrote that the resolutions of a monarch are subject to no inconsistency save for human nature; in assemblies, inconsistencies arise from the number. For in an assembly, as little as the absence of a few or the diligent appearance of a few of the contrary opinion, "undoes today all that was done yesterday".Civil war reduction

Thomas Hobbes wrote that a monarch cannot disagree with himself, out of envy or interest, but an assembly may and to such a height that may produce a civil war.Liberty

The International Monarchist League, founded in 1943, has always sought to promote monarchy on the grounds that it strengthens popular liberty, both in a democracy and in a dictatorship, because by definition the monarch is not beholden to politicians. British-American libertarian writer Matthew Feeney argues that European constitutional monarchies "have managed for the most part to avoid extreme politics"—specifically fascism, communism, and military dictatorship—"in part because monarchies provide a check on the wills of populist politicians" by representing entrenched customs and traditions. Feeny notes thatEuropean monarchies—such as the Danish, Belgian, Swedish, Dutch, Norwegian, and British—have ruled over countries that are among the most stable, prosperous, and free in the world.Socialist writer George Orwell argued a similar point, that constitutional monarchy is effective at preventing the development of fascism.

"The function of the King in promoting stability and acting as a sort of keystone in a non-democratic society is, of course, obvious. But he also has, or can have, the function of acting as an escape-valve for dangerous emotions. A French journalist said to me once that the monarchy was one of the things that have saved Britain from Fascism...It is at any rate possible that while this division of function exists a Hitler or a Stalin cannot come to power. On the whole the European countries which have most successfully avoided Fascism have been constitutional monarchies... I have often advocated that a Labour government, i.e. one that meant business, would abolish titles while retaining the Royal Family.’Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn took a different approach, arguing that liberty and equality are contradictions. As such, he argued that attempts to establish greater social equality through the Abolition of monarchy, abolishment of monarchy, ultimately results in a greater loss of liberty for citizens. He believed that equality can only be accomplished through the suppression of liberty, as humans are naturally unequal and hierarchical. Kuehnelt-Leddihn also believed that people are on average freer under monarchies than they are under democratic republics, as the latter tends to more easily become tyrannical through ochlocracy. In ''Liberty or Equality'', he writes:

There is little doubt that the American Congress or the French Chambers have a power over their nations which would rouse the envy of a Louis XIV or a George III, were they alive today. Not only prohibition, but also the income tax declaration, Selective Service System, selective service, obligatory schooling, the fingerprinting of blameless citizens, premarital blood tests—none of these totalitarian measures would even the royal absolutism of the seventeenth century have dared to introduce.Hans-Hermann Hoppe also argues that monarchy helps to preserve individual liberty more effectively than democracy.

Natural desire for hierarchy

In a 1943 essay in ''The Spectator'', "Equality", British author C.S. Lewis criticized egalitarianism, and its corresponding call for the abolition of monarchy, as contrary to human nature, writing,A man's reaction to Monarchy is a kind of test. Monarchy can easily be 'debunked'; but watch the faces, mark well the accents, of the debunkers. These are the men whose tap-root in Eden has been cut: whom no rumour of the polyphony, the dance, can reach—men to whom pebbles laid in a row are more beautiful than an arch...Where men are forbidden to honour a king they honour millionaires, athletes, or film-stars instead: even famous prostitutes or gangsters. For spiritual nature, like bodily nature, will be served; deny it food and it will gobble poison.

Political accountability

Oxford political scientists Petra Schleiter and Edward Morgan-Jones wrote that in monarchies, it is more common to hold elections than non-electoral replacements.Notable works

Notable works arguing in favor of monarchy include * Tony Abbott, Abbott, Tony (1995). ''The Minimal Monarchy: And Why It Still Makes Sense For Australia'' * Dante Alighieri, Alighieri, Dante (c. 1312). ''De Monarchia'' * Thomas Aquinas, Aquinas, Thomas (1267). ''De regno, ad regem Cypri, De Regno, to the King of Cyprus'' * Michael Auslin, Auslin, Michael (2014). ''America Needs a King'' * Jaime Balmes, Balmes, Jaime (1850). ''European Civilization: Protestantism and Catholicity Compared in their Effects on the Civilization of Europe'' * Robert Bellarmine, Bellarmine, Robert (1588). ''De Romano Pontifice, On the Roman Pontiff'' * Jean Bodin, Bodin, Jean (1576). ''The Six Books of the Republic'' * Vernon Bogdanor, Bogdanor, Vernon (1997). ''The Monarchy and the Constitution'' * Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne (1709). ''Politics Drawn from the Very Words of Holy Scripture'' * Charles I of England (1649). ''Eikon Basilike'' * Charles A. Coulombe, Coulombe, Charles A. (2016). ''Star-Spangled Crown: A Simple Guide to the American Monarchy'' * François-René de Chateaubriand, Chateaubriand, François-René de (1814). ''Of Buonaparte, and the Bourbons, and of the Necessity of Rallying Round Our Legitimate Princes'' * Ralph Adams Cram, Cram, Ralph Adams (1936). ''Invitation to Monarchy'' * Robert Filmer, Filmer, Robert (1680). ''Patriarcha'' * Thomas Hobbes, Hobbes, Thomas (1651). ''Leviathan

Leviathan ( ; ; ) is a sea serpent demon noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, and the pseudepigraphical Book of Enoch. Leviathan is of ...

''

* Hans Hermann-Hoppe, Hermann-Hoppe, Hans (2001). ''Democracy: The God That Failed''

* — (2014). ''From Aristocracy to Monarchy to Democracy: A Tale of Moral and Economic Folly and Decay''

* James VI and I (1598). ''The True Law of Free Monarchies''

* — (1599). ''Basilikon Doron''

* Jean, Count of Paris (2009). ''Un Prince Français''

* Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik von (1952). ''Liberty or Equality: The Challenge of Our Times''

* — (2000). ''Monarchy and War''

* Joseph de Maistre, Maistre, Joseph de (1797). ''Considerations on France''

* Pope Pius VI, Pius VI (1793). ''Pourquoi Notre Voix''

* Roger Scruton, Scruton, Roger (1991). ''A Focus of Loyalty Higher Than the State''

* Louis Gaston Adrien de Ségur, Ségur, Louis Gaston Adrien de (1871). ''Vive le Roi!''

* Eugenio Vegas Latapié, Vegas Latapiè, Eugenio (1983). ''Memorias politicas. El suicidio de la monarquia y la Segunda Republica''

* Peter Whittle (politician), Whittle, Peter (2011). ''Monarchy Matters''

Support for monarchy

Current monarchies

Former monarchies

The following is a list of former monarchies and their percentage of public support for monarchism.Notable monarchists

Several notable public figures who advocated for monarchy or are monarchists include:Arts and entertainment

* Honoré de Balzac, French novelist & playwright * Fyodor Dostoevsky, Russian novelist & essayist * Pedro Muñoz Seca, Spanish playwright * George MacDonald, British theologian and writer * C.S. Lewis, British theologian and writer * J.R.R. Tolkien, British writer * T.S. Eliot, American-British poet & writer * Salvador Dalí, Spanish artist * Hergé, Belgian cartoonist * Éric Rohmer, French filmmaker * Yukio Mishima, Japanese author * Joan Collins, English actress & author * Stephen Fry, English actor & authorClergy

* Thomas Aquinas, Italian Catholic priest & theologian * Robert Bellarmine, Italian Cardinal (Catholic Church), Cardinal & theologian * Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, French Bishop & theologian * Cardinal Mazarin, Jules Mazarin, Italian Cardinal & minister * André-Hercule de Fleury, French Cardinal & minister * Pope Pius VI, Pius VI, Italian Pope & ruler of the Papal States * Fabrizio Ruffo, Italian Cardinal & treasurer * Ercole Consalvi, Italian Cardinal Secretary of State * Pelagio Antonio de Labastida y Dávalos, Mexican Archbishop & Regent of the Second Mexican Empire * Louis Gaston Adrien de Ségur, French Bishop & writer * Louis Billot, French priest & theologian * Pope Pius XII, Pius XII, Italian Pope & sovereign of Vatican City * József Mindszenty, Hungarian Cardinal & Prince-primatePhilosophy

* Dante Alighieri, Italian poet & philosopher * Jean Bodin, French political philosopher * Robert Filmer, English political theorist * Thomas Hobbes, English philosopher * Joseph de Maistre, Savoyard philosopher & writer * Juan Donoso Cortés, Spanish politician & political theologian * Søren Kierkegaard, Danish philosopher & theologian * Charles Maurras, French author & philosopher * Kang Youwei, Chinese political thinker & reformer * Ralph Adams Cram, American architect & writer * Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Austrian political scientist & philosopher * Vernon Bogdanor, British political scientist & historian * Roger Scruton, English philosopher & writer * Hans Hermann-Hoppe, German-American political theorist * Charles A. Coulombe, American historian & authorPolitics

* François-René de Chateaubriand, French historian & Pious Establishments of France, Ambassador * Manuel Belgrano, Argentinian politician * Klemens von Metternich, Austrian List of heads of government under Austrian Emperors, Chancellor * Miguel Miramón, Mexican President of Mexico, President & military general * Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor of Germany, Chancellor * Juan Vázquez de Mella, Spanish politician & political theorist * Panagis Tsaldaris, Greek Prime Minister of Greece, Prime Minister * Winston Churchill, British Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Prime Minister of the U.K. * Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu, Romanian Prime Minister of Romania, Prime Minister * Salome Zourabichvili, Georgian President of Georgia, President * Tony Abbott, Australian Prime Minister of Australia, Prime Minister * Carla Zambelli, Brazilian politicianMonarchist movements and parties

* Action Française * Alfonsism * Alliance Royale * Australian Monarchist League * Australians for Constitutional Monarchy * Bonapartism * Black-Yellow Alliance * Carlism * Cavalier * Chouannerie * Conservative-Monarchist Club * Constantian Society * Constitutionalist Party of Iran * Druk Phuensum Tshogpa * Hawaiian sovereignty movement * Hovpartiet * International Monarchist League * Jacobitism * Koruna Česká (party) * Legality Movement * Legitimists, Legitimism * Liberal Democratic Party of Russia * Loyalism * Loyalist (American Revolution) * Miguelist * Monarchist League of Canada * Monarchist Party of Russia * Monarchy New Zealand * Movement for the Restoration of the Kingdom of Serbia * Nouvelle Action Royaliste * Orléanist, Orléanism * People's Alliance for Democracy * Rastriya Prajatantra Party * Royal Stuart Society * Royalist Party * Sanfedismo * Serbian Renewal Movement * Sonnō jōi * Tradition und Leben * Traditionalist Communion * Ultra-royalistCriticism

Criticism of monarchy can be targeted against the general form of government—monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

—or more specifically, to list of monarchies, particular monarchical governments as controlled by hereditary royal family, royal families. In some cases, this criticism can be curtailed by legal restrictions and be considered criminal speech, as in lèse-majesté. Monarchies in Europe and their underlying concepts, such as the Divine Right of Kings, were often criticized during the Age of Enlightenment, which notably paved the way to the French Revolution and the proclamation of the abolition of the monarchy in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. Earlier, the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

had seen the Patriot (American Revolution), Patriots suppress the Loyalists and expel all royal officials. In this century, monarchies are present in the world in many forms with different degrees of royal power and involvement in civil affairs:

* Absolute monarchies in Brunei, Eswatini, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the Vatican City;

* Constitutional monarchies in the United Kingdom and its sovereign's Commonwealth Realms, and in Belgium, Denmark, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Monaco, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, and others.

The twentieth century, beginning with the 1917 February Revolution in Russia and accelerated by two world wars, saw many European countries replace their monarchies with republics, while others replaced their absolute monarchies with constitutional monarchies. Reverse movements have also occurred, with brief returns of the monarchy in France under the Bourbon Restoration in France, Bourbon Restoration, the July Monarchy, and the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the government of France from 1852 to 1870. It was established on 2 December 1852 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of France under the French Second Republic, who proclaimed hi ...

, the Stuarts after the English Civil War and the Bourbons in Spain after the Francisco Franco, Franco dictatorship.

See also

* Dark Enlightenment * List of dynasties * Reactionary modernismNotes

References

{{Authority control Monarchism, ja:君主主義