Modern Egypt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

According to most scholars the history of modern

Europe External Programme with Africa On 19 December 2020, Egypt was reportedly encouraging Sudan to support the

in JSTOR

* Baer, Gabriel. ''Studies in the Social History of Modern Egypt'' (U Chicago Press, 1969). * Daly, Martin W. ed. ''The Cambridge history of Egypt. Vol. 2: Modern Egypt from 1517 to the end of the twentieth century.'' (1998). * Goldschmidt Jr., Arthur. ''Biographical Dictionary of Modern Egypt'' (1999) * Karakoç, Ulaş. "Industrial growth in interwar Egypt: first estimate, new insights" ''European Review of Economic History'' (2018) 22#1 53–72

online

* Landes, David. ''Bankers and Pashas: International Finance and Economic Imperialism in Egypt'' (Harvard UP, 1980). * Marlowe, John. ''A History of Modern Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Relations: 1800-1956'' (Archon Books, 1965). * Morewood, Steve. ''The British Defence of Egypt, 1935-40: Conflict and Crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean'' (2008). * Royal Institute of International Affairs. ''Great Britain and Egypt, 1914-1951'' (2nd ed. 1952) als

online free

* Thornhill, Michael T. "Informal Empire, Independent Egypt and the Accession of King Farouk." ''Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History'' 38#2 (2010): 279–302. * Tignore, Robert L. ''Egypt: A Short History'' (2011) * Vatikiotis, P.J. ''The History of Modern Egypt: From Muhammad Ali to Mubarak'' (4th ed. 1991) {{Authority control Modern Egypt

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

dates from the start of the rule of Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and social activist. A global cultural icon, widely known by the nickname "The Greatest", he is often regarded as the gr ...

in 1805 and his launching of Egypt's modernization project that involved building a new army and suggesting a new map for the country, though the definition of Egypt's modern history has varied in accordance with different definitions of modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular Society, socio-Culture, cultural Norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the ...

. Some scholars date it as far back as 1516 with the Ottomans' defeat of the Mamlūks in 1516–17.

Muhammad Ali's dynasty became practically independent from Ottoman rule, following his military campaigns against the Empire and his ability to enlist large-scale armies, allowing him to control both Egypt and parts of North Africa and the Middle East. In 1882, the Khedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brought an end to the short- ...

became part of the British sphere of influence in the region, a situation that conflicted with its position as an autonomous vassal state of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

The country became a British protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

in 1915 and achieved full independence in 1922, becoming a kingdom under the rule of Muhammad Ali's dynasty, which lasted until 1952.

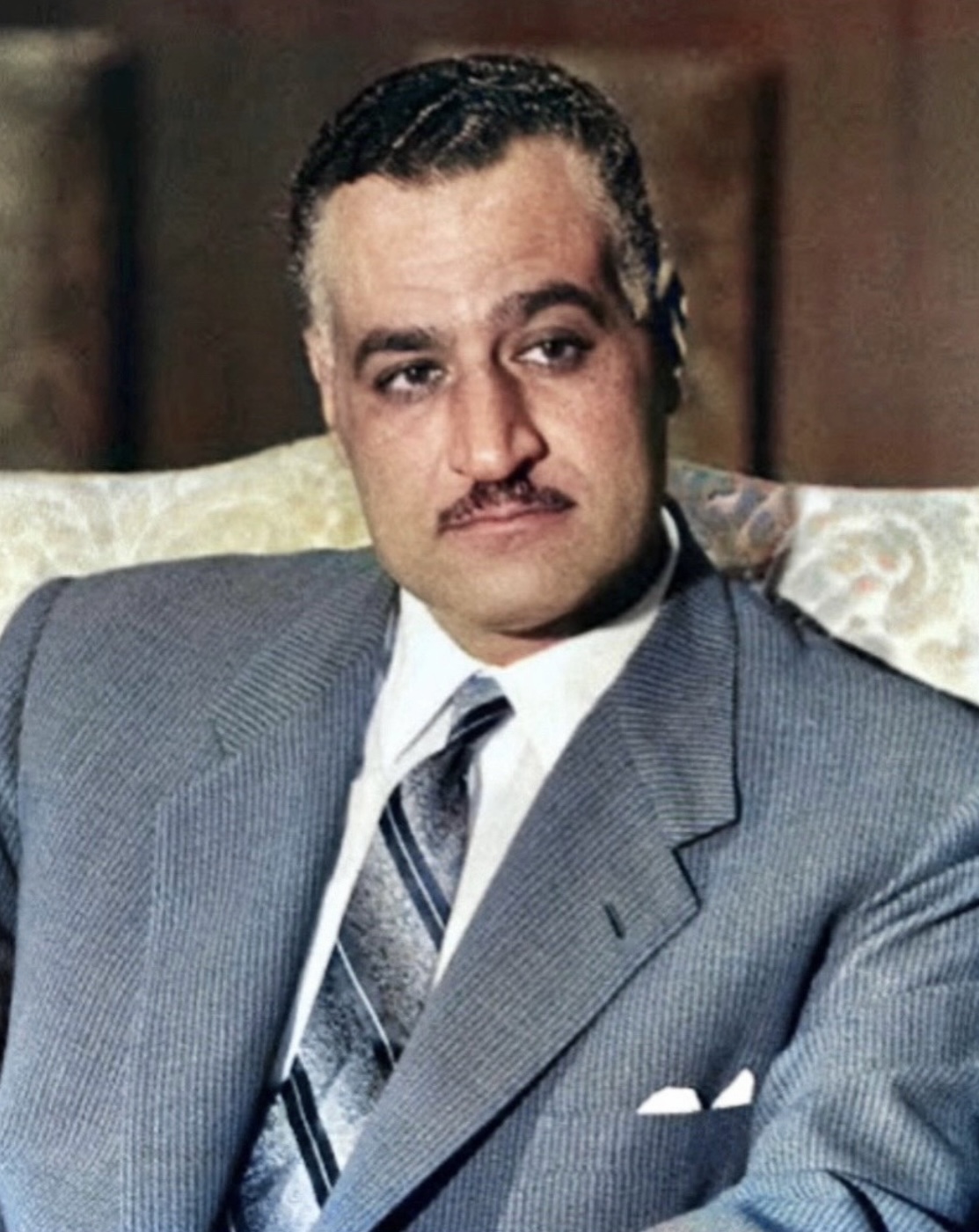

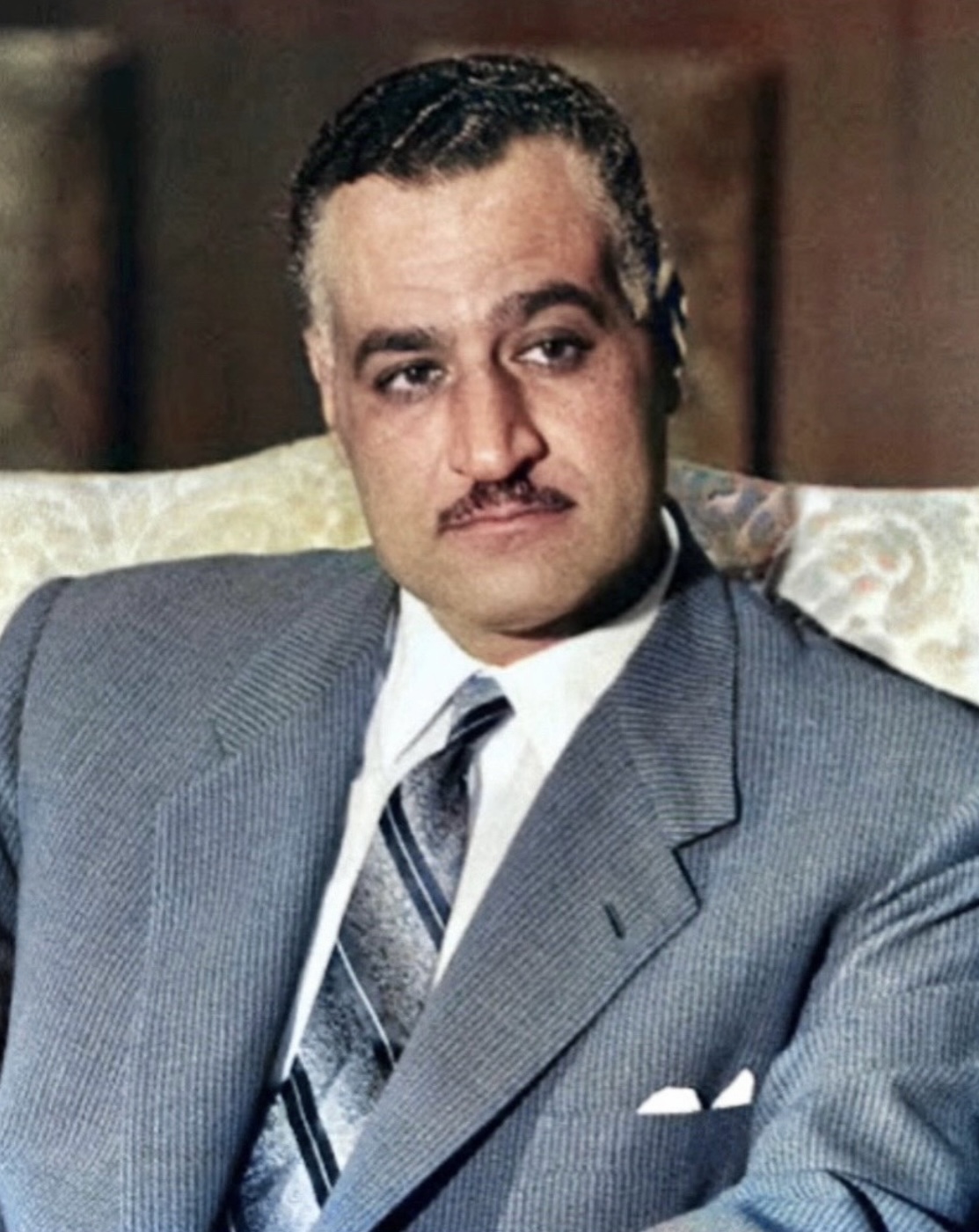

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

ended monarchical rule and established a republic in Egypt, known as the Republic of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Gaza Strip of Palest ...

, following the 1952 Egyptian revolution

The Egyptian revolution of 1952, also known as the 1952 coup d'état () and the 23 July Revolution (), was a period of profound political, economic, and societal change in Egypt. On 23 July 1952, the revolution began with the toppling of King ...

. Egypt was ruled autocratically by three presidents

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*''Præsidenten ...

over the following six decades: by Nasser from 1954 until his death in 1970, by Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar es-Sadat (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until Assassination of Anwar Sadat, his assassination by fundame ...

from 1971 until his assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

in 1981, and by Hosni Mubarak

Muhammad Hosni El Sayed Mubarak (; 4 May 1928 – 25 February 2020) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the fourth president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011 and the 41st Prime Minister of Egypt, prime minister from 1981 to ...

from 1981 until his resignation in the face of the 2011 Egyptian revolution

The 2011 Egyptian revolution, also known as the 25 January Revolution (;), began on 25 January 2011 and spread across Egypt. The date was set by various youth groups to coincide with the annual Egyptian "Police holiday" as a statement against ...

.

In 2012, after more than a year under the interim government of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF; , ', also Higher Council of the Armed Forces) is a Statutory authority, statutory body of between 20 and 25 Senior officer, senior Officer (armed forces), officers of the Egyptian Armed Forces, and ...

, with Field Marshal Tantawi as its chairman, elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

were held and the Islamist Mohamed Morsi

Mohamed Mohamed Morsi Eissa Al-AyyatThe spellings of his first and last names vary. survey of 14 news organizations plus Wikipedia in July 2012Abdel Fattah El-Sisi

Abdel Fattah Saeed Hussein Khalil El-Sisi (born 19 November 1954) is an Egyptian politician and retired military officer who has been serving as the sixth and current president of Egypt since 2014.

After the 2011 Egyptian revolution and 201 ...

Khedivate of Egypt

British administration

In 1882 opposition to European control led to growing tension amongst notable Egyptians, the most dangerous opposition coming from the army. A large military demonstration in September 1881 forced the Khedive Tewfiq to dismiss his prime minister. In April 1882, France and the United Kingdom sent warships toAlexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

to bolster the Khedive amidst a turbulent climate, spreading fear of invasion throughout the country.

Tawfiq moved to Alexandria for fear of his own safety as army officers led by Ahmed Urabi

Ahmed Urabi (; Arabic: ; 31 March 1841 – 21 September 1911), also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha, was an Egyptian military officer. He was the first political and military leader in Egypt to rise from the ''fellahin'' (peasantry). Urabi p ...

began to take control of the government. By June Egypt was in the hands of nationalists opposed to European domination of the country. The naval bombardment of Alexandria by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

had little effect on the opposition which led to the landing of a British expeditionary force at both ends of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

in August 1882.

The British succeeded in defeating the Egyptian Army

The Egyptian Army (), officially the Egyptian Ground Forces (), is the land warfare branch (and largest service branch) of the Egyptian Armed Forces. Until the declaration of the Republic and the abolishment of the monarchy on 18 June 1953, it w ...

at Tel El Kebir in September and took control of the country putting Tawfiq back in control. The purpose of the invasion had been to restore political stability to Egypt under a government of the Khedive and international controls which were in place to streamline Egyptian financing since 1876. It is unlikely that the British expected a long-term occupation from the outset. However, Lord Cromer

Earl of Cromer is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, held by members of the British branch of the Anglo-German Baring banking family.

It was created in 1901 for Evelyn Baring, 1st Viscount Cromer, long time British Consul-General ...

, Britain's Chief Representative in Egypt at the time, viewed Egypt's financial reforms as part of a long-term objective. Cromer took the view that political stability needed financial stability, and embarked on a programme of long-term investment in Egypt's productive resources, above all in the cotton economy, the mainstay of the country's export earnings.

In 1906 the Denshawai incident

The Denshawai incident is the name given to a dispute which occurred in 1906 between British Army officers and Egyptian villagers in Denshawai, Egypt, which would later become of great significance in the nationalist and anti-colonial consciou ...

provoked a questioning of British rule in Egypt.

British administration ended nominally with the establishment of a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

and the installation of sultan Hussein Kamel in 1914, but a British military presence in Egypt lasted until June 1956.

Sultanate of Egypt

In 1914 as a result of the declaration of war with the Ottoman Empire, of which Egypt was nominally a part, Britain declared a Protectorate over Egypt and deposed the anti-British Khedive,Abbas Hilmi II

Abbas Helmy II (also known as ''ʿAbbās Ḥilmī Pāshā'', ; 14 July 1874 – 19 December 1944) was the last Khedive of Egypt and the Sudan, ruling from 8January 1892 to 19 December 1914. In 1914, after the Ottoman Empire joined the Cent ...

, replacing him with his uncle Husayn Kamel, who was made Sultan of Egypt by the British. Egypt subsequently declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire.

A group known as the Wafd

WAFD (100.3 FM, "The Summit") is a hot adult contemporary formatted broadcast radio station licensed to Webster Springs, West Virginia, serving East Central West Virginia. WAFD is owned and operated by Summit Media Broadcasting, LLC. In late 2 ...

Delegation attended the Paris Peace Conference of 1919

Paris () is the capital and largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the fourth-most populous city in the European Union and the 30th most densely popul ...

to demand Egypt's independence. Included in the group was political leader, Saad Zaghlul

Saad Zaghloul Pasha ( / ; also ''Sa'd Zaghloul Pasha ibn Ibrahim'') (July 1857 – 23 August 1927) was an Egyptian revolutionary and statesman. He was the leader of Egypt's nationalist Wafd Party, and served as the first Honorary President of ...

, who would later become prime minister. When the group was arrested and deported to the island of Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

, a huge uprising occurred in Egypt.

From March to April 1919, there were mass demonstrations that became uprisings. This is known in Egypt as the 1919 Revolution. Almost daily demonstrations and unrest continued throughout Egypt for the remainder of the Spring. To the surprise of the British authorities, Egyptian women also demonstrated, led by Huda Sha‘rawi

Huda Sha'arawi or Hoda Sha'rawi (, ; 23 June 1879 – 12 December 1947) was a pioneering Egyptian feminist leader, suffragette, nationalist, and founder of the Egyptian Feminist Union.

Early life and marriage

Huda Sha'arawi was born Nour Al- ...

(1879–1947), who would become the leading feminist voice in Egypt in the first half of the twentieth century. The first women's demonstration was held on Sunday, 16 March 1919, and was followed by yet another one on Thursday, 20 March 1919. Egyptian women would continue to play an important and increasingly public nationalist role throughout the spring and summer of 1919 and beyond.

Initially, the British authorities deployed the police force in Cairo in response to the demonstrations, though control was soon handed over to Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a military formation of the British Empire, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–1915), at the ...

(EEF) troops under the command of Major-General H. D. Watson. By the summer of 1919, the disturbances had largely been suppressed; more than 800 Egyptians had been killed, as well as 31 European civilians and 29 British soldiers. In November 1919, the Milner Commission

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a very important role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and ear ...

was sent to Egypt by the British to attempt to resolve the situation. In 1920, Lord Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a very important role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and ear ...

submitted his report to Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

, the British Foreign Secretary, recommending that the protectorate should be replaced by a treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, convention ...

of alliance. As a result, Curzon agreed to receive an Egyptian mission headed by Zaghlul and Adli Pasha to discuss the proposals. The mission arrived in London in June 1920 and the agreement was concluded in August 1920.

In February 1921, the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

approved the agreement and Egypt was asked to send another mission to London with full powers to conclude a definitive treaty. Adli Pasha led this mission, which arrived in June 1921. However, the Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

delegates at the 1921 Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

had stressed the importance of maintaining control over the Suez Canal Zone and Curzon could not persuade his Cabinet colleagues to agree to any terms that Adli Pasha was prepared to accept. The mission returned to Egypt in disgust.

Kingdom of Egypt

In December 1921, the British authorities in Cairo imposed martial law and once again deported Zaghlul. Demonstrations again led to violence. In deference to the growing nationalism and at the suggestion of the High Commissioner,Lord Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army officer and imperial governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in World War I, in which he led the Britis ...

, the UK unilaterally declared Egyptian independence on 28 February 1922. Sultan Fuad I

Fuad I ( ''Fu’ād al-Awwal''; 26 March 1868 – 28 April 1936) was the Sultan and later King of Egypt and the Sudan. The ninth ruler of Egypt and Sudan from the Muhammad Ali dynasty, he became Sultan in 1917, succeeding his elder brother Hus ...

was subsequently proclaimed King of Egypt.

Britain, however, continued to retain a strong influence in the newborn Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt () was the legal form of the Egyptian state during the latter period of the Muhammad Ali dynasty's reign, from the United Kingdom's recognition of Egyptian independence in 1922 until the abolition of the monarchy of Eg ...

. British guided the king and retained control of the Canal Zone, Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

and Egypt's external and military affairs. King Fuad died in 1936 and King Farouk

Farouk I (; ''Fārūq al-Awwal''; 11 February 1920 – 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 1936 and reigning until his ...

inherited the throne at the age of sixteen. Alarmed by the Second Italo-Abyssinian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression waged by Italy against Ethiopia, which lasted from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Ita ...

when Italy invaded Ethiopia, he signed the Anglo-Egyptian treaty, requiring Britain to withdraw all troops from Egypt by 1949, except at the Suez Canal.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, British troops used Egypt as its primary base for all Allied operations throughout the region. British troops were withdrawn to the Suez Canal area in 1947, but nationalist, anti-British feelings continued to grow after the war.

Republic of Egypt

Coup of 1952

On 22–26 July 1952, a group of disaffected army officers (the "free officers") led by Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrewKing Farouk

Farouk I (; ''Fārūq al-Awwal''; 11 February 1920 – 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 1936 and reigning until his ...

, whom the military blamed for Egypt's poor performance in the 1948 war with Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

. Popular expectations for immediate reforms led to the workers' riots in Kafr Dawar

Kafr El Dawwar ( ) is a major industrial city and municipality on the Nile Delta in the Beheira Governorate of northern Egypt. Located approximately 30 km from Alexandria, the municipality has a population of about 265,300 inhabitants a ...

on 12 August 1952, which resulted in two death sentences. Following a brief experiment with civilian rule, the Free Officers abrogated the 1953 constitution and declared Egypt a republic on 18 June 1953.

Nasser's rule

Emergence of Arab socialism

Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

evolved into a charismatic leader, not only of Egypt but of the Arab world, promoting and implementing "Arab socialism

Arab socialism () is a political ideology based on the combination of pan-Arabism or Arab nationalism and socialism. The term "Arab socialism" was coined by Michel Aflaq, the principal founder of Ba'athism and the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Part ...

."

When the United States held up military sales in reaction to Egyptian neutrality regarding the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

concluded an arms deal with Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

in September 1955.

When the US and the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

withdrew their offer to help finance the Aswan High Dam

The Aswan Dam, or Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. When it was completed, it was the tallest earthen dam in the world, surpassing the Chatug ...

in mid-1956, Nasser nationalized the privately owned Suez Canal Company

Suez (, , , ) is a seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest city of the ...

. The crisis

A crisis (: crises; : critical) is any event or period that will lead to an unstable and dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, or all of society. Crises are negative changes in the human or environmental affairs, especially when ...

that followed, exacerbated by growing tensions with Israel over guerrilla attacks from Gaza

Gaza may refer to:

Places Palestine

* Gaza Strip, a Palestinian territory on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea

** Gaza City, a city in the Gaza Strip

** Gaza Governorate, a governorate in the Gaza Strip

Mandatory Palestine

* Gaza Sub ...

and Israeli reprisals, support for the FLN's war of liberation against the French in Algeria

French Algeria ( until 1839, then afterwards; unofficially ; ), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of History of Algeria, Algerian history when the country was a colony and later an integral part of France. French rule lasted until ...

and against Britain's presence in the Arab world, resulted in the invasion of Egypt in October by France, Britain, and Israel. This was also known as the Suez War

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

. According to the historian Abd aI-Azim Ramadan, Nasser's decision to nationalize the Suez Canal was his alone, made without political or military consultation. The events leading up to the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, as other events during Nasser's rule, showed Nasser's inclination to solitary decision making. He considers Nasser to be far from a rational, responsible leader.

United Arab Republic

In 1958 Egypt joined with the Republic of Syria and annexed the Gaza Strip, ruled by theAll-Palestine Government

The All-Palestine Government (, ') was established on 22 September 1948, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, to govern the Egyptian-controlled territory in Gaza, which Egypt had on the same day declared as the All-Palestine Protectorate. It w ...

, to form a state called the United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 to 1971. It was initially a short-lived political union between Republic of Egypt (1953–1958), Egypt (including Occupation of the Gaza Strip by the United Ara ...

. It existed until Syria's secession in 1961, although Egypt continued to be known as the UAR until 1971.

Nasser helped establish with India and Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

of developing countries in September 1961, and continued to be a leading force in the movement until his death.

Regional intervention

Nasser had looked to a regime change in Yemen since 1957 and finally put his desires into practice in January 1962 by giving the Free Yemen Movement office space, financial support, and radio air time.Anthony Nutting

Sir Harold Anthony Nutting, 3rd Baronet (11 January 1920 – 23 February 1999) was a British diplomat and Conservative Party politician who served as a Member of Parliament from 1945 until 1956. He was a Minister of State for Foreign Affairs ...

's biography of Gamal Abdel-Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

identifies several factors that led the Egyptian President to send expeditionary forces to Yemen. These included the unraveling of the union with Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

in 1961, which dissolved his United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 to 1971. It was initially a short-lived political union between Republic of Egypt (1953–1958), Egypt (including Occupation of the Gaza Strip by the United Ara ...

(UAR), damaging his prestige. A quick decisive victory in Yemen could help him recover leadership of the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

. Nasser also had his reputation as an anti-colonial

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholars of decolon ...

force, setting his sights on ridding South Yemen, and its strategic port city of Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

, of British forces.

Nasser ruled as an autocrat but remained extremely popular within Egypt and throughout the Arab world. His willingness to stand up to the Western powers and to Israel won him support throughout the region. However, Nasser's independent foreign policy led to Israel launching the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

in 1967. This conflict saw the Egyptian, Syrian and Jordanian armed forces routed by the Israelis.

Israel afterward occupied the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai ( ; ; ; ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a land bridge between Asia and Afri ...

and the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

from Egypt, Golan Heights

The Golan Heights, or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in t ...

from Syria, and West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

from Jordan. This defeat was a severe blow to Nasser's prestige both at home and abroad. Following the defeat, Nasser made a dramatic offer to resign, which was only retracted in the face of mass demonstrations urging him to stay. The last three years of his control over Egypt were far more subdued.

Sadat era

Sadat era refers to the presidency of Muhammad Anwar al-Sadat, the eleven-year period of Egyptian history spanning from the death of president Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970, through Sadat's assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 October 1981. Sadat's presidency saw many changes in Egypt's direction, reversing some of the economic and political principles of Nasserism by breaking with Soviet Union to make Egypt an ally of the United States, initiated the peace process with Israel, re-instituting the multi-party system and abandoning socialism by launching the Infitah economic policy.Under Soviet influence

After Nasser's death, another of the original revolutionary " free officers," Vice PresidentAnwar el-Sadat

Muhammad Anwar es-Sadat (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until his assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 Oc ...

, was elected President of Egypt. Nasser's supporters in government settled on Sadat as a transitional figure that (they believed) could be manipulated easily. However, Sadat had a long term in office and many changes in mind for Egypt and by some astute political moves was able to institute a "corrective revolution", (announced on 15 May 1971) which purged the government, political and security establishments of the most ardent Nasserists

Nasserism ( ) is an Arab nationalist and Arab socialist political ideology based on the thinking of Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the two principal leaders of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, and Egypt's second President of Egypt, President. Spa ...

. Sadat encouraged the emergence of an Islamist movement which had been suppressed by Nasser. Believing Islamists to be socially conservative he gave them "considerable cultural and ideological autonomy" in exchange for political support.

Following the disastrous Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

of 1967, Egypt waged a War of Attrition

The War of Attrition (; ) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from 1967 to 1970.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, no serious diplomatic efforts were made to resolve t ...

in the Suez Canal zone. In 1971, three years into this war, Sadat endorsed in a letter the peace proposals of UN negotiator Gunnar Jarring

Gunnar Valfrid Jarring (12 October 1907 – 29 May 2002) was a Swedish diplomat and Turkologist.

Early life

Jarring was born on 12 October 1907 in Brunnby, Malmöhus County, Sweden, the son of Gottfrid Jönsson, a farmer, and his wife Betty ( ...

, which seemed to lead to a full peace with Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

on the basis of Israel's withdrawal to its pre-war borders. This peace initiative failed as neither Israel nor the United States of America accepted the terms as discussed then. To provide Israel with more incentive to negotiate with Egypt and return the Sinai to it, and also because the Soviets had refused Sadat's requests for more military support, Sadat expelled the Soviet military advisers from Egypt and proceeded to bolster his army for a renewed confrontation with Israel.

In the months before the 1973 war Sadat engaged in a diplomatic offensive and by the fall of 1973 had support for a war of more than a hundred states, including most of the countries of the Arab League, Non-Aligned Movement, and Organization of African Unity. Syria agreed to join Egypt in attacking Israel.

In October 1973, Egypt's armed forces achieved initial successes in the Crossing and advanced 15 km, reaching the depth of the range of safe coverage of its own air force. After Syrian forces were being repulsed, the Syrian government urged Sadat to move his forces deeper into Sinai. Without air cover, the Egyptian army suffered huge losses. In spite of huge losses they kept advancing, creating the chance to open a gap between army forces. That gap was exploited by a tank division led by Ariel Sharon, and he and his tanks managed to penetrate, reaching Suez City. In the meantime, the United States initiated a strategic airlift to provide replacement weapons and supplies to Israel and appropriate $2.2 billion in emergency aid. OPEC oil ministers, led by Saudi Arabia retaliated with an oil embargo against the US. A UN resolution supported by the United States and the Soviet Union called for an end to hostilities and for peace talks to begin. On 4 March 1974 Israel withdrew the last of its troops from the west side of the Suez Canal and 12 days later Arab oil ministers announced the end of the embargo against the United States. For Sadat and many Egyptians the war was much more a victory than a draw, as the military objective of capturing a foothold of the Sinai was achieved.

Under Western influence

In foreign relations Sadat instigated momentous change. President Sadat shifted Egypt from a policy of confrontation with Israel to one of peaceful accommodation through negotiations. Following the Sinai Disengagement Agreements of 1974 and 1975, Sadat created a fresh opening for progress by his dramatic visit toJerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

in November 1977. This led to the invitation from President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

of the United States to President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Begin

Begin or Bégin may refer to:

People

*Begin (surname)

Music

* Begin (band), a Japanese pop trio

* ''Begin'' (David Archuleta album)

* ''begin'' (Riyu Kosaka album)

* ''Begin'' (Lion Babe album)

* ''Begin'' (The Millennium album)

* ''beGin'' ...

to enter trilateral negotiations at Camp David.

The outcome was the historic Camp David accord

The Camp David Accords were a pair of political agreements signed by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin on 17 September 1978, following twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the country retrea ...

s, signed by Egypt and Israel and witnessed by the US on 17 September 1978. The accords led to 26 March 1979, signing of the Egypt–Israel peace treaty

The Egypt–Israel peace treaty was signed in Washington, D.C., United States, on 26 March 1979, following the 1978 Camp David Accords. The Egypt–Israel treaty was signed by Anwar Sadat, President of Egypt, and Menachem Begin, Prime Minist ...

, by which Egypt regained control of the Sinai in May 1982. Throughout this period, US–Egyptian relations steadily improved, and Egypt became one of America's largest recipients of foreign aid. Sadat's willingness to break ranks by making peace with Israel earned him the enmity of most other Arab states, however. In 1977, Egypt fought a short border war with Libya.

Sadat used his immense popularity with the Egyptian people to try to push through vast economic reforms that ended the socialistic controls of Nasserism

Nasserism ( ) is an Arab nationalism, Arab nationalist and Arab socialism, Arab socialist List of political ideologies, political ideology based on the thinking of Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the two principal leaders of the Egyptian Revolution ...

. Sadat introduced greater political freedom and a new economic policy, the most important aspect of which was the infitah

''Infitah'' ( ', "openness"), or Law 43 of 1974, was Egyptian president Anwar Sadat's policy of "opening the door" to private investment in Egypt in the years after the 1973 October War (Yom Kippur War) with Israel. ''Infitah'' was accompanie ...

or "open door". This relaxed government controls over the economy and encouraged private investment. While the reforms created a wealthy and successful upper class and a small middle class, these reforms had little effect upon the average Egyptian who began to grow dissatisfied with Sadat's rule. In 1977, Infitah policies led to massive spontaneous riots ('Bread Riots') involving hundreds of thousands of Egyptians when the state announced that it was retiring subsidies on basic foodstuffs.

Liberalization also included the reinstitution of due process and the legal banning of torture. Sadat dismantled much of the existing political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

and brought to trial a number of former government officials accused of criminal excesses during the Nasser era. Sadat tried to expand participation in the political process in the mid-1970s but later abandoned this effort. In the last years of his life, Egypt was wracked by violence arising from discontent with Sadat's rule and sectarian tensions, and it experienced a renewed measure of repression including extra judicial arrests.

Conflict with the Muslim Brotherhood

Another change Sadat made from the Nasser era was a bow towards the Islamic revival. Sadat loosened restrictions on the Muslim Brotherhood, allowing it to publish a monthly magazine, al-Dawa, which appeared regularly until September 1981 (although he did not allow the group's reconstitution.) In the late 1970s, he began calling himself 'The Believer President' and signing his name ''Mohammad'' Anwar Sadat.' He ordered Egypt's state-run television to interrupt programs withSalat

''Salah'' (, also spelled ''salat'') is the practice of formal ibadah, worship in Islam, consisting of a series of ritual prayers performed at prescribed times daily. These prayers, which consist of units known as rak'a, ''rak'ah'', include ...

(call to prayer) on the screen five times a day and to increase religious programming. Under his rule local officials banned the sale of alcohol except at places catering to foreign tourists in more than half of Egypt's 26 governorates. 2

Mubarak era

Presidential inauguration

On 6 October 1981, President Sadat was assassinated by Islamic extremists.Hosni Mubarak

Muhammad Hosni El Sayed Mubarak (; 4 May 1928 – 25 February 2020) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the fourth president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011 and the 41st Prime Minister of Egypt, prime minister from 1981 to ...

, Vice President since 1975 and an air force commander during the October 1973 war, was elected president later that month. He was subsequently confirmed by popular referendum for three more 6-year terms, most recently in September 2005. The results of the referendums are however of questionable validity as they, with the exception of the one conducted in September 2005, listed only Mubarak as the sole candidate.

Mubarak maintained Egypt's commitment to the Camp David peace process, while at the same time re-establishing Egypt's position as an Arab leader. Egypt was readmitted to the Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

in 1989. Egypt also has played a moderating role in such international forums as the UN and the Nonaligned Movement.

1990s – economic reforms and struggle with radical Islamists

From 1991, Mubarak undertook an ambitious domestic economic reform program to reduce the size of the public sector and expand the role of the private sector. During the 1990s, a series of International Monetary Fund arrangements, coupled with massive external debt relief resulting from Egypt's participation in the Gulf War coalition, helped Egypt improve its macroeconomic performance. Theeconomy of Egypt

The economy of Egypt is a developing country, developing, mixed economy, combining private enterprise with centralized economic planning and government regulation. It is the second-largest economy in Africa, and List of countries by GDP (nominal ...

flourished during the 1990s and 2000s. The Government of Egypt tamed inflation bringing it down from double-digit to a single digit. Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP) increased fourfold between 1981 and 2006, from US$1355 in 1981, to US$2525 in 1991, to US$3686 in 2001 and to an estimated US$4535 in 2006.

There was less progress in political reform. The November 2000 People's Assembly elections saw 34 members of the opposition win seats in the 454-seat assembly, facing a clear majority of 388 ultimately affiliated with the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP). A constitutional amendment in May 2005 changed the presidential election to a multicandidate popular vote rather than a popular validation of a candidate nominated by the People's Assembly and on 7 September Mubarak was elected for another six-year term with 87 percent of the popular vote, followed by a distant but strong showing by Ayman Nour

Ayman Abd El Aziz Nour (, ; born 5 December 1964) is an Egyptian politician, a former member of the Egyptian Parliament, founder and chairman of the El Ghad party.

Nour was the first person to compete against President Hosni Mubarak in the 20 ...

, leader of the opposition Ghad Party and a well-known rights activist.

Shortly after mounting an unprecedented presidential campaign, Nour was jailed on forgery charges critics called phony; he was released on 18 February 2009. Brotherhood members were allowed to run for parliament in 2005 as independents, garnering 88 seats, or 20 percent of the People's Assembly.

The opposition parties

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''th ...

have been weak and divided and are not yet credible alternatives to the NDP. The Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ('' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar, Imam and schoolteacher Hassan al-Banna in 1928. Al-Banna's teachings s ...

, founded in Egypt in 1928, had remained an illegal organization and may not be recognized as a political party (current Egyptian law prohibits the formation of political parties based on religion). Members are known publicly and openly speak their views. Members of the Brotherhood have been elected to the People's Assembly and local councils as independents. The Egyptian political opposition also includes groups and popular movements such as Kefaya

Kefaya ( ''kefāya'', , "enough") is the unofficial moniker of the Egyptian Movement for Change ( ''el-Haraka el-Masreyya men agl el-Taghyeer''), a grassroots coalition which prior to the 2011 revolution drew its support from across Egypt's po ...

and the 6 April Youth Movement

The April 6 Youth Movement () is an Egyptian activist group established in Spring 2008 to support the workers in El-Mahalla El-Kubra, an industrial town, who were planning to strike on 6 April.

Activists called on participants to wear black and ...

, although they are somewhat less organized than officially registered political parties. Bloggers, or cyberactivists as Courtney C. Radsch terms them, have also played an important political opposition role, writing, organizing, and mobilizing public opposition.

Decrease of influence

President Mubarak had tight, autocratic control over Egypt. However, a dramatic drop in support for Mubarak and his domestic economic reform program increased with surfacing news about his son Alaa being extremely corrupt and favored in government tenders and privatization. As Alaa started getting out of the picture by 2000, Mubarak's second sonGamal Gamal () is an Arabic surname and male given name. Notable people with this name include:

Surname

* Amr Gamal, (born 1991) Egyptian footballer

* Mazen Gamal (born 1986), Egyptian squash player

*Raghda Gamal, Yemeni journalist and poet

Given name

* ...

started rising in the National Democratic Party and succeeded in getting a newer generation of neo-liberals into the party and eventually the government. Gamal Mubarak branched out with a few colleagues to set up Medinvest Associates Ltd., which manages a private equity fund, and to do some corporate finance consultancy work.

Civil unrest 2011-2014

2011 revolution and aftermath

Beginning on 25 January 2011, a series of street demonstrations, protests, and civil disobedience acts have taken place in Egypt, with organizers counting on the Tunisian uprising to inspire the crowds to mobilize. The demonstrations andriot

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

s were reported to have started over police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or Public order policing, a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, b ...

, state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

laws, unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work du ...

, desire to raise the minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. List of countries by minimum wage, Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation b ...

, lack of housing, food inflation

Food inflation is a type of inflation that affects food items. It often the most noticeable form of inflation, and tends to impact lower income individuals the hardest. Common causes include poor harvest, war, increasing energy prices, and food be ...

, corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

, lack of freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, and poor living conditions.

The protests' main goal was to oust President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Hosni Mubarak

Muhammad Hosni El Sayed Mubarak (; 4 May 1928 – 25 February 2020) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the fourth president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011 and the 41st Prime Minister of Egypt, prime minister from 1981 to ...

's regime.

On 11 February 2011, Mubarak resigned and fled Cairo. Vice President Omar Suleiman announced that Mubarak had stepped down and that the Egyptian military

The Egyptian Armed Forces () are the military forces of the Arab Republic of Egypt. The Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces directs (a) Egyptian Army forces, (b) the Egyptian Navy, (c) Egyptian Air Force and (d) Egyptian Air Defense Forces. Th ...

would assume control of the nation's affairs in the short term. (See also '' 2011 revolution''.) Jubilant celebrations broke out in Tahrir Square

Tahrir Square (, ; ), also known as Martyr Square, is a public town square in downtown Cairo, Egypt. The square has been the location and focus for political demonstrations. The 2011 Egyptian revolution and the resignation of President of Egypt, ...

at the news. Mubarak may have left Cairo for Sharm el-Sheikh

Sharm El Sheikh (, , literally "bay of the Sheikh"), alternatively rendered Sharm el-Sheikh, Sharm el Sheikh, or Sharm El-Sheikh, is an Egyptian city on the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula, in South Sinai Governorate, on the coastal strip alo ...

the previous night, before or shortly after the airing of a taped speech in which Mubarak vowed he would not step down or leave.

On 13 February 2011, the high level military command of Egypt announced that both the constitution and the parliament of Egypt had been dissolved. The parliamentary election was to be held in September.

A constitutional referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or advis ...

was held on 19 March 2011. On 28 November 2011, Egypt held its first parliamentary election since the previous regime had been in power. Turnout was high and there were no reports of irregularities or violence, although members of some parties broke the ban on campaigning at polling places by handing out pamphlets and banners.

A constituent assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

, founded on 26 March 2012, started to work for implementing a new constitution. Presidential elections

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The ...

, were held in March–June 2012, with a final runoff between former prime minister Ahmed Shafik

Air Marshal Ahmed Mohamed Shafik ZakiAlso spelled: ''Shafiq''. (, ; born 25 November 1941) is an Egyptian politician and former presidential candidate. He was a senior commander in the Egyptian Air Force and later served as Prime Minister of ...

and Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ('' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar, Imam and schoolteacher Hassan al-Banna in 1928. Al-Banna's teachings s ...

parliamentarian Mohamed Morsi

Mohamed Mohamed Morsi Eissa Al-AyyatThe spellings of his first and last names vary. survey of 14 news organizations plus Wikipedia in July 2012Mohamed Morsi

Mohamed Mohamed Morsi Eissa Al-AyyatThe spellings of his first and last names vary. survey of 14 news organizations plus Wikipedia in July 2012edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchies, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement". ''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu ...

that dissolved the country's elected parliament and calling on lawmakers back into session.

On 10 July 2012, the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt

The Supreme Constitutional Court (, ''Al Mahkama Al Dustūrīya El ‘Ulyā'') is an independent judicial body in Egypt, located in the Cairo suburb of Maadi.

The Supreme Constitutional Court is the highest judicial authority in the Arab Republi ...

negated the decision by President Mohamed Morsi to call the nation's parliament back into session.

On 2 August 2012, Egypt's Prime Minister Hisham Qandil announced his 35-member cabinet comprising 28 newcomers including four from the influential Muslim Brotherhood, six others and the former military ruler Tantawi as the Defence Minister from the previous Government.

2012-2013 Egyptian protests

On 22 November 2012, EgyptianMohamed Morsi

Mohamed Mohamed Morsi Eissa Al-AyyatThe spellings of his first and last names vary. survey of 14 news organizations plus Wikipedia in July 2012Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

drafting the new constitution. The declaration also requires a retrial of those accused in the Mubarak-era killings of protesters, who had been acquitted, and extends the mandate of the constituent assembly by two months. Additionally, the declaration authorizes Morsi to take any measures necessary to protect the revolution. Liberal and secular groups previously walked out of the constitutional constituent assembly because they believed that it would impose strict Islamic practices, while Muslim Brotherhood backers threw their support behind Morsi.

A constitutional referendum was held in two rounds on 15 and 22 December 2012, with 64% support, and 33% against. It was signed into law by a presidential decree issued by Morsi on 26 December 2012.

The move has been criticized by Mohamed ElBaradei

Mohamed Mostafa ElBaradei (, ; born 17 June 1942) is an Egyptian law scholar and diplomat who served as the vice president of Egypt on an interim basis from 14 July 2013 until his resignation on 14 August 2013.

He was the Director General of ...

who stated "Morsi today usurped all state powers & appointed himself Egypt's new pharaoh" on his Twitter feed. The move has led to massive protests and violent action throughout Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

.

After Morsi

On 30 June 2013, on the first anniversary of the election of Morsi, millions of protesters across Egypt took to the streets and demanded the immediate resignation of the president. On 1 July, theEgyptian Armed Forces

The Egyptian Armed Forces () are the military forces of the Egypt, Arab Republic of Egypt. The Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces directs (a) Egyptian Army forces, (b) the Egyptian Navy, (c) Egyptian Air Force and (d) Egyptian Air Defense Forces. ...

issued a 48-hour ultimatum that gave the country's political parties until 3 July to meet the demands of the Egyptian people. The presidency rejected the Egyptian Army's 48-hour ultimatum, vowing that the president would pursue his own plans for national reconciliation to resolve the political crisis. On 3 July, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

Abdel Fattah Saeed Hussein Khalil El-Sisi (born 19 November 1954) is an Egyptian politician and retired military officer who has been serving as the sixth and current president of Egypt since 2014.

After the 2011 Egyptian revolution and 201 ...

, head of the Egyptian Armed Forces, announced that he had removed Morsi from power, suspended the constitution and would be calling new presidential and Shura Council elections and named Supreme Constitutional Court's leader, Adly Mansour

Adly Mahmoud Mansour (, ; born 23 December 1945) is an Egyptian judge and politician who served as the president (or chief justice) of the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt. He also served as interim president of Egypt from 4 July 2013 to 8 ...

as acting president. Mansour was sworn in on 4 July 2013.

During the months after the coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

, a new constitution was prepared, which took effect on 18 January 2014. After that, presidential

Presidential may refer to:

* "Presidential" (song), a 2005 song by YoungBloodZ

* Presidential Airways (charter), an American charter airline based in Florida

* Presidential Airways (scheduled), an American passenger airline active in the 1980s

* ...

and parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

elections have to be held within 6 months.

El-Sisi Presidency

In theelections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

of June 2014 El-Sisi won with a percentage of 96.1%. On 8 June 2014, Abdel Fatah el-Sisi was officially sworn in as Egypt's new president. Under President el-Sisi, Egypt has implemented a rigorous policy of controlling the border to the Gaza Strip, including the dismantling of tunnels between the Gaza strip and Sinai.

In April 2018, El-Sisi was re-elected by landslide in election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

with no real opposition. In April 2019, Egypt’s parliament extended presidential terms from four to six years. President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi was also allowed to run for third term in next election in 2024.

Under El-Sisi Egypt is said to have returned to authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

. New constitutional reforms have been implemented, meaning strengthening the role of military and limiting the political opposition. The constitutional changes were accepted in a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

in April 2019.

In December 2020, final results of the parliamentary election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

confirmed a clear majority of the seats for Egypt’s Mostaqbal Watn ( Nation’s Future) Party, which strongly supports president El-Sisi. The party even increased its majority, partly because of new electoral rules.

During the 2020–2021 Tigray War, Egypt was also involved. On 19 December 2020, an EEPA

The Europe External Programme with Africa and Europe External Policy Advisors, both called EEPA, are two closely associated Belgian-based non-governmental organizations that aim to encourage the European Union's involvement in human rights in ge ...

report stated, based on testimonials of three Egyptian officials and one European diplomat, that the UAE used its base in Assab

Assab or Aseb (, ) is a port city in the Southern Red Sea Region of Eritrea. It is situated on the west coast of the Red Sea.

Languages spoken in Assab are predominantly Afar language, Afar, Tigrinya language, Tigrinya, and Arabic. After the Ita ...

(Eritrea) to launch drones strikes against Tigray. The investigative platform Bellingcat

Bellingcat (stylised bell¿ngcat) is a Netherlands-based investigative journalism group that specialises in fact-checking and open-source intelligence (OSINT). It was founded by British citizen journalist and former blogger Eliot Higgins in Ju ...

confirmed the presence of Chinese-produced drones at the UAE's military base in Assab, Eritrea. Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

ian officials were concerned about strengthening ties between the UAE and Israel. They fear that both countries will collaborate in the construction of an alternative to the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

, starting from Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

in Israel.Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 31 - 20 DecemberEurope External Programme with Africa On 19 December 2020, Egypt was reportedly encouraging Sudan to support the

TPLF

The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF; ), also known as the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front, is a left-wing ethnic nationalist, paramilitary group, and the former ruling party of Ethiopia. It was classified as a terrorist organization ...

in Tigray. It wants to strengthen a joint position in relation to negotiations on the GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a chronic upper gastrointestinal disease in which stomach content persistently and regularly flows up into the esophagus, resulting in symptoms and/or ...

Dam, which impacts both countries downstream.

See also

*History of Egypt

Egypt, one of the world’s oldest civilizations, was unified around 3150 BC by King Narmer. It later came under Persian, Greek, Roman, and Islamic rule before joining the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Controlled by Britain in the late 19th century, ...

*Egyptian Constitution of 1923

The Constitution of 1923 was a history of the Egyptian Constitution, constitution of Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt from 1923–1952.Harvey Henry Smith. Area Handbook for the United Arab Republic (Egypt).' U.S. Government Printing Office, 1970. p. 192. ...

*Liberalism in Egypt

Liberalism in Egypt or Egyptian liberalism is a political ideology that traces its beginnings to the 19th century.

History

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (also spelt Tahtawy; 1801–1873) was an Egyptians, Egyptian writer, teacher, translator, Egyptolog ...

*Terrorism in Egypt

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war a ...

References

Further reading

*Bruton, Henry J. . "Egypt's Development in the Seventies" ''Economic Development and Cultural Change

''Economic Development and Cultural Change (EDCC)'' is a peer-reviewed journal that publishes studies that use modern theoretical and empirical approaches to examine both the determinants and the effects of various dimensions of economic developme ...

''. 31#4 (1983), pp. 679–704.in JSTOR

* Baer, Gabriel. ''Studies in the Social History of Modern Egypt'' (U Chicago Press, 1969). * Daly, Martin W. ed. ''The Cambridge history of Egypt. Vol. 2: Modern Egypt from 1517 to the end of the twentieth century.'' (1998). * Goldschmidt Jr., Arthur. ''Biographical Dictionary of Modern Egypt'' (1999) * Karakoç, Ulaş. "Industrial growth in interwar Egypt: first estimate, new insights" ''European Review of Economic History'' (2018) 22#1 53–72

online

* Landes, David. ''Bankers and Pashas: International Finance and Economic Imperialism in Egypt'' (Harvard UP, 1980). * Marlowe, John. ''A History of Modern Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Relations: 1800-1956'' (Archon Books, 1965). * Morewood, Steve. ''The British Defence of Egypt, 1935-40: Conflict and Crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean'' (2008). * Royal Institute of International Affairs. ''Great Britain and Egypt, 1914-1951'' (2nd ed. 1952) als

online free

* Thornhill, Michael T. "Informal Empire, Independent Egypt and the Accession of King Farouk." ''Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History'' 38#2 (2010): 279–302. * Tignore, Robert L. ''Egypt: A Short History'' (2011) * Vatikiotis, P.J. ''The History of Modern Egypt: From Muhammad Ali to Mubarak'' (4th ed. 1991) {{Authority control Modern Egypt