Mob Lynching on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle (often in the form of a hanging) for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in all societies.

Lynching in the United States, In the United States, where the word ''lynching'' likely originated, lynchings of African Americans became frequent in the Southern United States, South during the period after the Reconstruction era, especially during the nadir of American race relations.

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle (often in the form of a hanging) for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in all societies.

Lynching in the United States, In the United States, where the word ''lynching'' likely originated, lynchings of African Americans became frequent in the Southern United States, South during the period after the Reconstruction era, especially during the nadir of American race relations.

He was accused, however, of ethnic prejudice in his handling of Welsh Americans, Welsh miners. William Lynch (Lynch law), William Lynch from Virginia claimed that the phrase was first used in a 1780 compact signed by him and his neighbors in Pittsylvania County. A 17th-century legend of James Lynch fitz Stephen, who was Mayor of Galway in Ireland in 1493, says that when his son was convicted of murder, the mayor hanged him from his own house. The story was proposed by 1904 as the origin of the word "lynch". It is dismissed by etymologists, both because of the distance in time and place from the alleged event to the word's later emergence, and because the incident did not constitute a lynching in the modern sense. The archaic verb ''linch'', to beat severely with a pliable instrument, to chastise or to maltreat, has been proposed as the etymological source; but there is no evidence that the word has survived into modern times, so this claim is also considered implausible. Since the 1970s, and especially since the 1990s, there has been a false etymology claiming that the word lynching comes from a fictitious William Lynch speech that was given by an especially brutal slaveholder to other slaveholders to explain how to control their slaves. Although a real person named William Lynch might have been the origin of the word lynching, the real life William Lynch definitely did not give this speech, and it is unknown whether the real William Lynch even owned slaves at all.

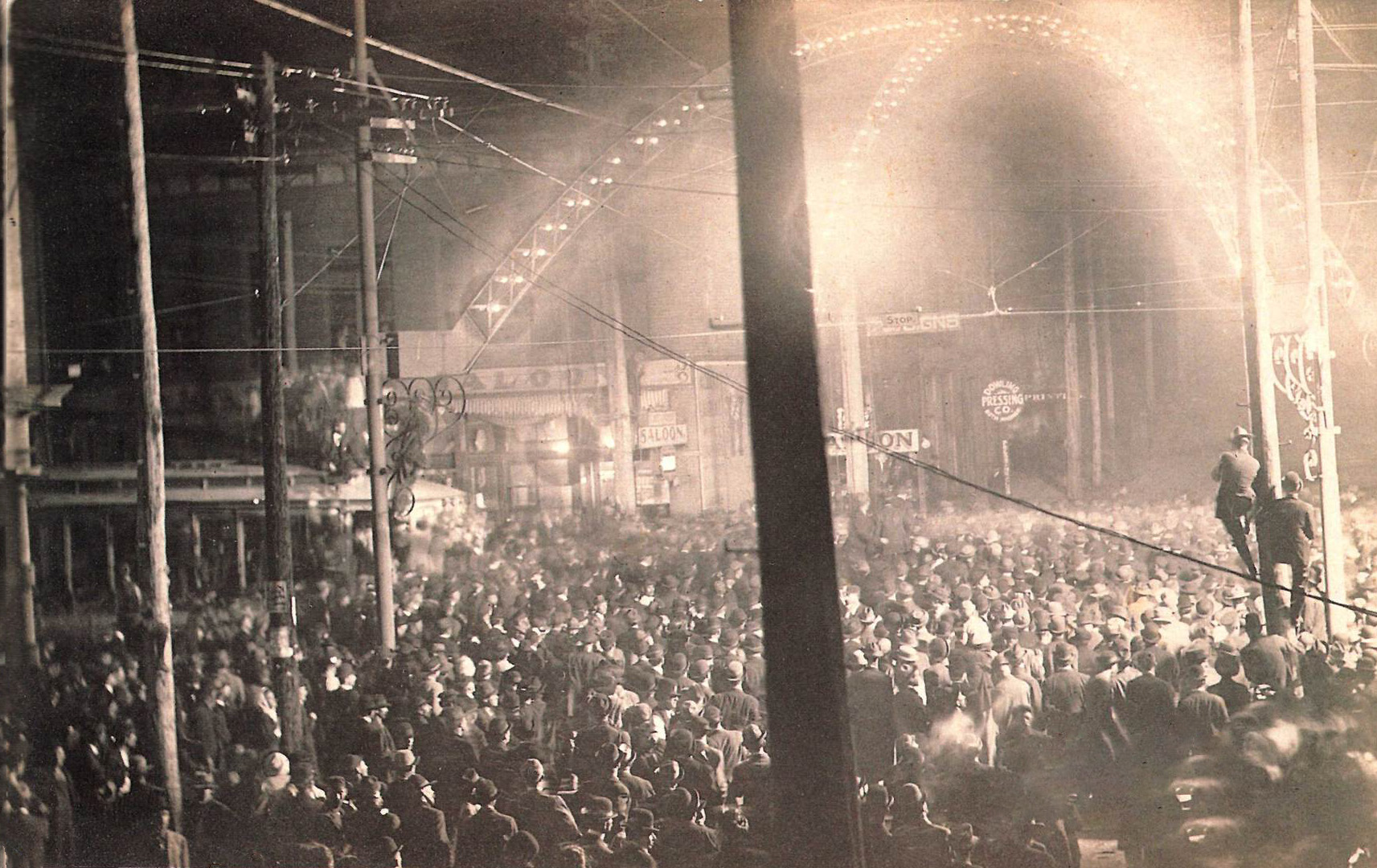

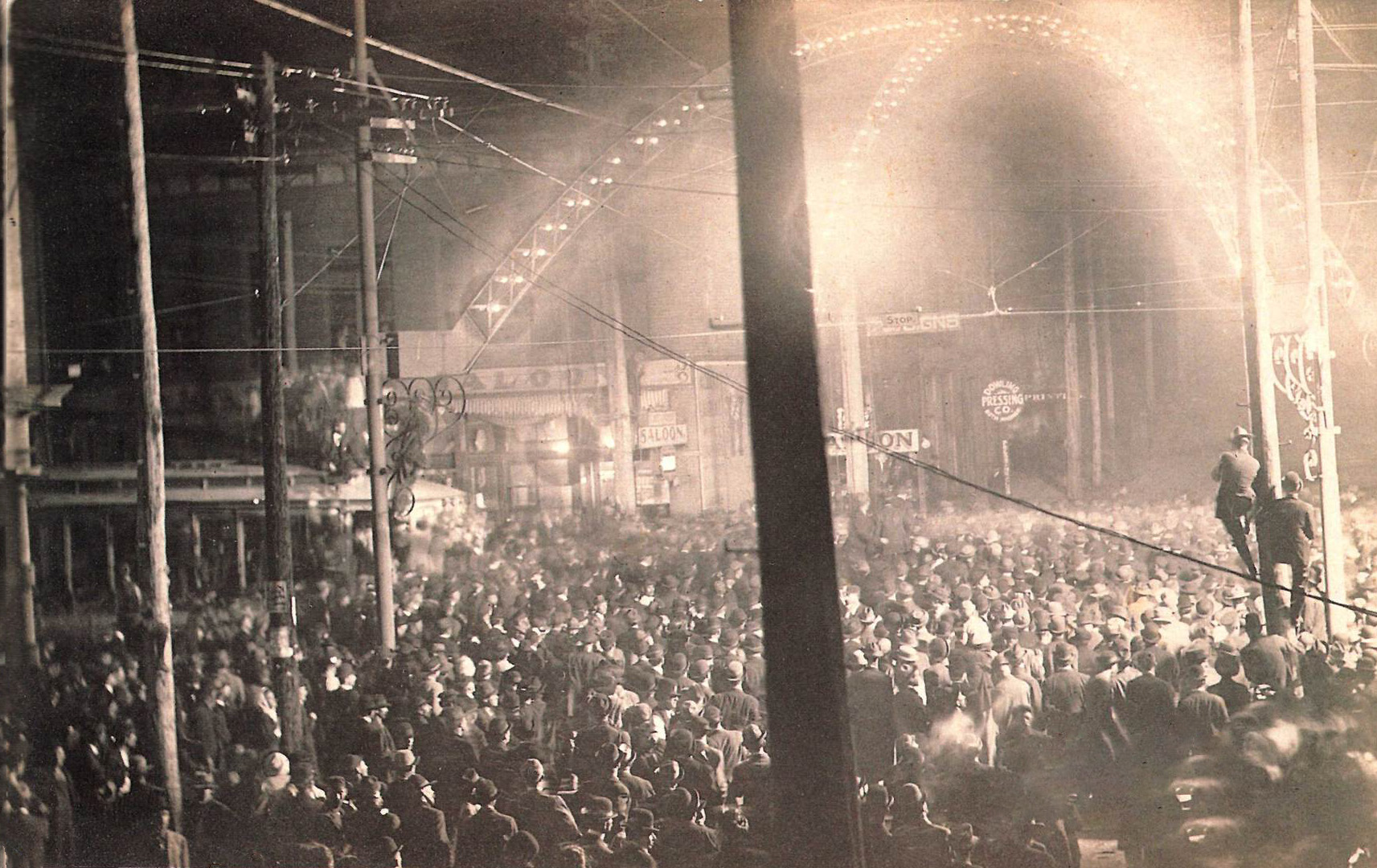

Lynchings took place in the United States both before and after the American Civil War, most commonly in Southern states and Western frontier settlements and most frequently in the late 19th century. They were often performed by self-appointed commissions, Ochlocracy, mobs, or vigilantes as a form of punishment for presumed criminal offenses. From 1883 to 1941 there were 4,467 victims of lynching. Of these, 4,027 were male, and 99 female. 341 were of unknown sex but are assumed to be likely male. In terms of ethnicity, 3,265 were black, 1,082 were white, 71 were Mexican or of Mexican descent, 38 were Native American, ten were Chinese, and one was Japanese. At the first recorded lynching, in St. Louis, Missouri, St. Louis in 1835, a Black man named McIntosh who killed a deputy sheriff while being taken to jail was captured, chained to a tree, and burned to death on a corner lot downtown in front of a crowd of over 1,000 people.

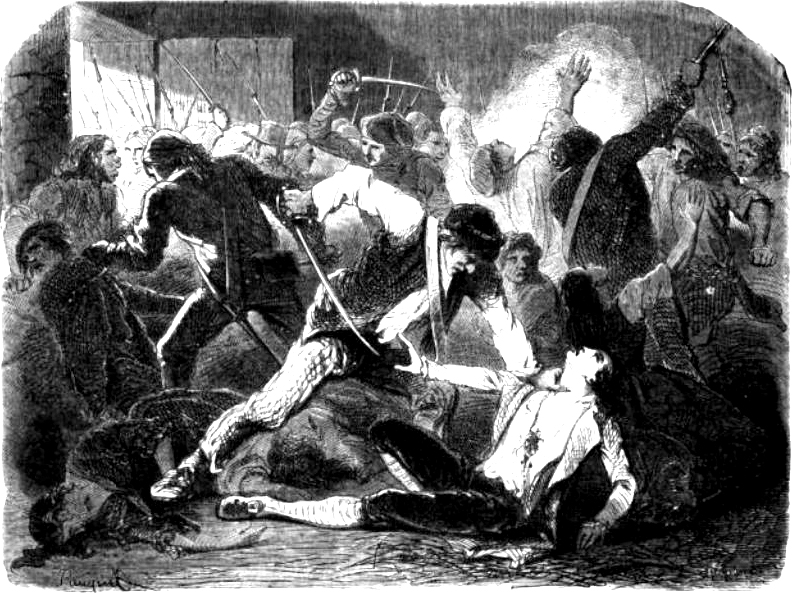

Universal suffrage indicated the beginning of mass lynching across southern United States. The rise to mobs of outrage such as the "red shirt" bands began to appear in many southern states at the time of when voting became a right for black men, a key historical turn of events that gave uprise to lynching. Initially intended as scare tactics, this outrage continues to grow more and more violent to the point of men being take from their homes, beaten, exiled, and even assassinated.

Mob violence arose as a means of enforcing White supremacy and frequently verged on systematic political terrorism. After the American Civil War, secret white supremacist terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, previously known as the "red-shirt bands", instigated extrajudicial assaults and killings due to a perceived loss of white power in America. Mobs usually alleged crimes for which they lynched Black people in order to instill fear. In the late 19th century, however, journalist Ida B. Wells showed that many presumed crimes were either exaggerated or had not even occurred. The magnitude of the extralegal violence which occurred during election campaigns, to prevent blacks from voting, reached epidemic proportions. The ideology behind lynching was directly connected to the denial of political and social equality, as stated forthrightly in 1900 by United States Senator and former governor of South Carolina Benjamin Tillman:

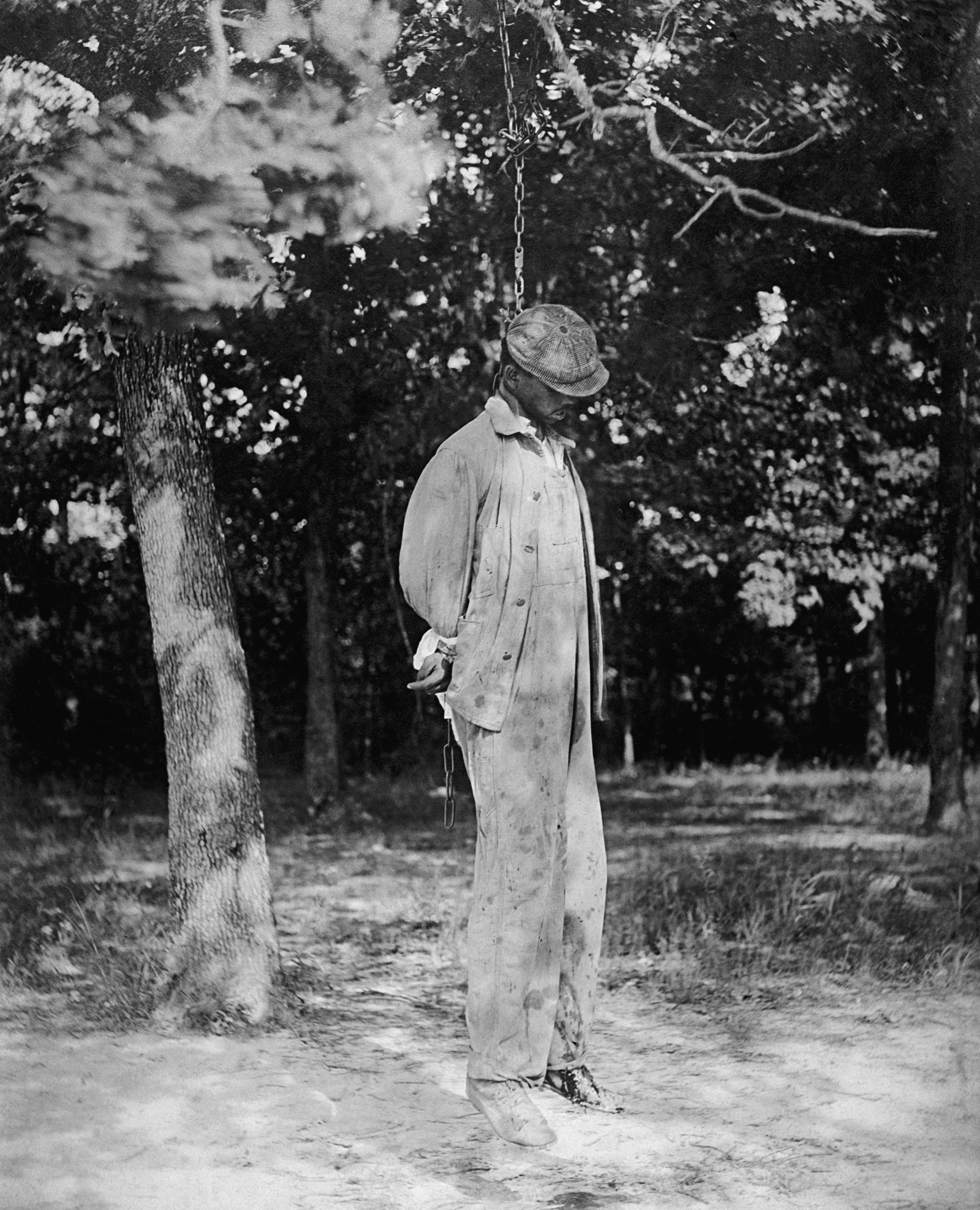

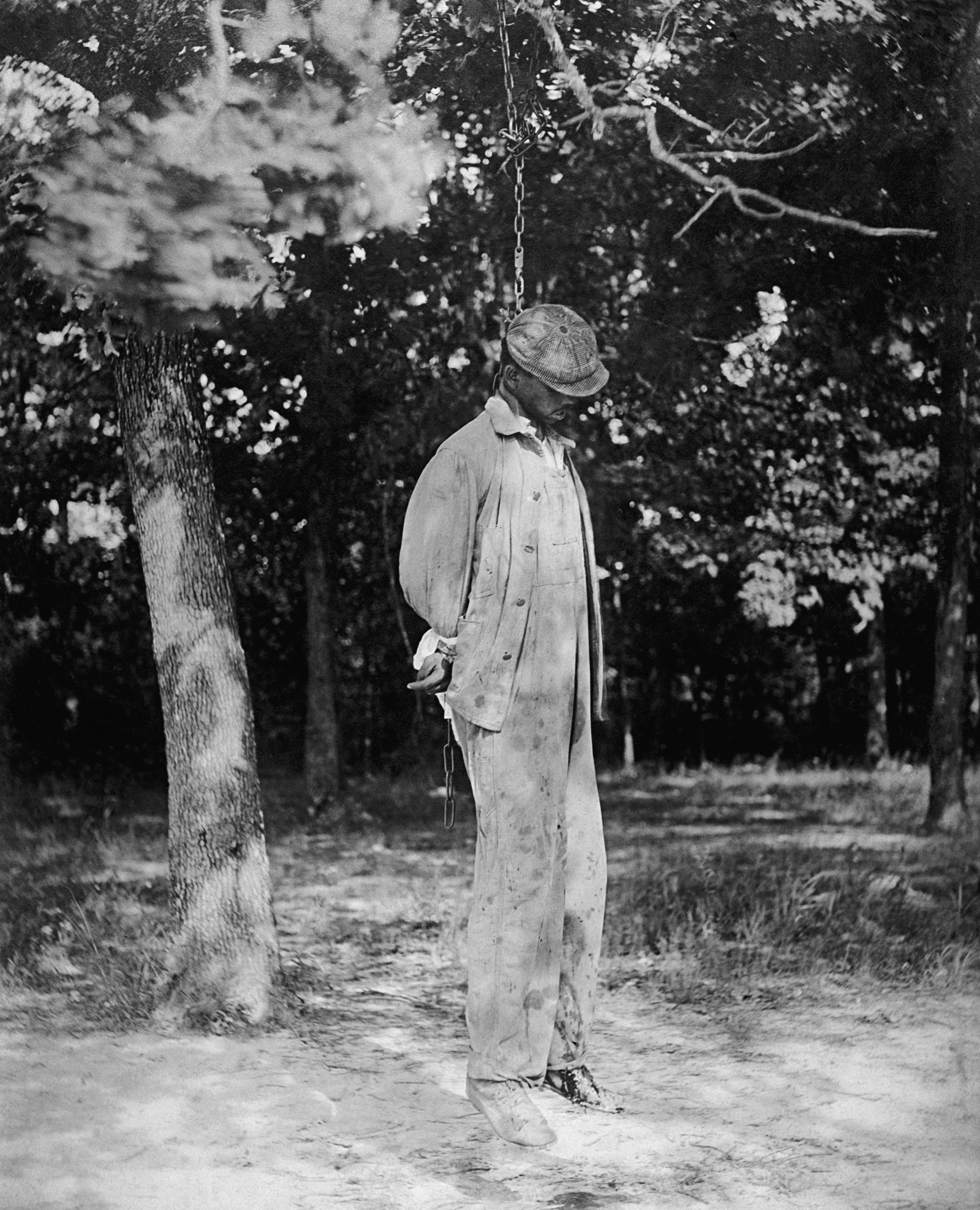

Members of mobs that participated in lynchings often took photographs of what they had done to their victims. Souvenir taking, such as the taking of pieces of rope, clothing, branches and sometimes Human trophy collecting, body parts was not uncommon. Some of those photographs were published and sold as lynching postcard, postcards.

Lynchings took place in the United States both before and after the American Civil War, most commonly in Southern states and Western frontier settlements and most frequently in the late 19th century. They were often performed by self-appointed commissions, Ochlocracy, mobs, or vigilantes as a form of punishment for presumed criminal offenses. From 1883 to 1941 there were 4,467 victims of lynching. Of these, 4,027 were male, and 99 female. 341 were of unknown sex but are assumed to be likely male. In terms of ethnicity, 3,265 were black, 1,082 were white, 71 were Mexican or of Mexican descent, 38 were Native American, ten were Chinese, and one was Japanese. At the first recorded lynching, in St. Louis, Missouri, St. Louis in 1835, a Black man named McIntosh who killed a deputy sheriff while being taken to jail was captured, chained to a tree, and burned to death on a corner lot downtown in front of a crowd of over 1,000 people.

Universal suffrage indicated the beginning of mass lynching across southern United States. The rise to mobs of outrage such as the "red shirt" bands began to appear in many southern states at the time of when voting became a right for black men, a key historical turn of events that gave uprise to lynching. Initially intended as scare tactics, this outrage continues to grow more and more violent to the point of men being take from their homes, beaten, exiled, and even assassinated.

Mob violence arose as a means of enforcing White supremacy and frequently verged on systematic political terrorism. After the American Civil War, secret white supremacist terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, previously known as the "red-shirt bands", instigated extrajudicial assaults and killings due to a perceived loss of white power in America. Mobs usually alleged crimes for which they lynched Black people in order to instill fear. In the late 19th century, however, journalist Ida B. Wells showed that many presumed crimes were either exaggerated or had not even occurred. The magnitude of the extralegal violence which occurred during election campaigns, to prevent blacks from voting, reached epidemic proportions. The ideology behind lynching was directly connected to the denial of political and social equality, as stated forthrightly in 1900 by United States Senator and former governor of South Carolina Benjamin Tillman:

Members of mobs that participated in lynchings often took photographs of what they had done to their victims. Souvenir taking, such as the taking of pieces of rope, clothing, branches and sometimes Human trophy collecting, body parts was not uncommon. Some of those photographs were published and sold as lynching postcard, postcards.

In Liverpool, a series of List of ethnic riots, race riots broke out in 1919 after the end of the World War I, First World War between White and Black sailors, many of whom had been demobilized. After a Black sailor had been stabbed by two White sailors in a pub for refusing to give them a cigarette, his friends attacked them the next day in revenge, wounding a policeman in the process. The Liverpool City Police, police responded by launching raids on lodging houses in primarily Black neighborhoods, with casualties on both sides. A White lynch mob gathered outside the houses during the raids and chased a Black sailor, Charles Wootton, into the River Mersey, Mersey River where he drowned. The Charles Wootton College in Liverpool has been named in his memory.

In 1944, Wolfgang Rosterg, a German prisoner of war known to be unsympathetic to the Nazi Germany, Nazi regime, was lynched by other German prisoners of war in Cultybraggan Camp, a prisoner-of-war camp in Comrie, Perth and Kinross, Comrie, Scotland. At the end of the World War II, Second World War, five of the perpetrators were Hanging, hanged at Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville Prison – the largest multiple execution in 20th-century Britain.

The situation is less clear with regards to reported "lynchings" in Germany. Propaganda in Nazi Germany, Nazi propaganda sometimes tried to depict state-sponsored violence as spontaneous lynchings. The most notorious instance of this was "Kristallnacht", which the government portrayed as the result of "popular wrath" against Jews, but it was carried out in an organized and planned manner, mainly by Sturmabteilung, SA and Schutzstaffel, SS men. Similarly, the approximately 150 confirmed murders of surviving crew members of crashed Allied aircraft in revenge for what Nazi propaganda called Strategic bombing during World War II, "Anglo-American bombing terror" were chiefly conducted by German officials and members of the police or the Gestapo, although civilians sometimes took part in them. The execution of enemy aircrew without trial in some cases had been ordered by Adolf Hitler, Hitler personally in May 1944. It was publicly announced that enemy pilots would no longer be protected from "public wrath". There were secret orders issued that prohibited policemen and soldiers from interfering in favor of the enemy in conflicts between civilians and Allies of World War II, Allied forces, or prosecuting civilians who engaged in such acts. In summary:

:...the assaults on crashed allied aviators were not typically acts of revenge for the bombing raids which immediately preceded them. [...] The perpetrators of these assaults were usually National Socialist officials, who did not hesitate to get their own hands dirty. The lynching murder in the sense of self-mobilizing communities or urban quarters was the exception.

Corporals killings, On March 19, 1988, two plain-clothes British soldiers drove straight towards a Provisional IRA funeral procession near Milltown Cemetery in Andersonstown, Belfast. The men were mistaken for Special Air Service members, surrounded by the crowd, dragged out, beaten, kicked, stabbed and eventually shot dead at a waste ground.

Lynching of members of the Turkish Armed Forces occurred in the aftermath of the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, 2016 Turkish ''coup d'état'' attempt.

In Liverpool, a series of List of ethnic riots, race riots broke out in 1919 after the end of the World War I, First World War between White and Black sailors, many of whom had been demobilized. After a Black sailor had been stabbed by two White sailors in a pub for refusing to give them a cigarette, his friends attacked them the next day in revenge, wounding a policeman in the process. The Liverpool City Police, police responded by launching raids on lodging houses in primarily Black neighborhoods, with casualties on both sides. A White lynch mob gathered outside the houses during the raids and chased a Black sailor, Charles Wootton, into the River Mersey, Mersey River where he drowned. The Charles Wootton College in Liverpool has been named in his memory.

In 1944, Wolfgang Rosterg, a German prisoner of war known to be unsympathetic to the Nazi Germany, Nazi regime, was lynched by other German prisoners of war in Cultybraggan Camp, a prisoner-of-war camp in Comrie, Perth and Kinross, Comrie, Scotland. At the end of the World War II, Second World War, five of the perpetrators were Hanging, hanged at Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville Prison – the largest multiple execution in 20th-century Britain.

The situation is less clear with regards to reported "lynchings" in Germany. Propaganda in Nazi Germany, Nazi propaganda sometimes tried to depict state-sponsored violence as spontaneous lynchings. The most notorious instance of this was "Kristallnacht", which the government portrayed as the result of "popular wrath" against Jews, but it was carried out in an organized and planned manner, mainly by Sturmabteilung, SA and Schutzstaffel, SS men. Similarly, the approximately 150 confirmed murders of surviving crew members of crashed Allied aircraft in revenge for what Nazi propaganda called Strategic bombing during World War II, "Anglo-American bombing terror" were chiefly conducted by German officials and members of the police or the Gestapo, although civilians sometimes took part in them. The execution of enemy aircrew without trial in some cases had been ordered by Adolf Hitler, Hitler personally in May 1944. It was publicly announced that enemy pilots would no longer be protected from "public wrath". There were secret orders issued that prohibited policemen and soldiers from interfering in favor of the enemy in conflicts between civilians and Allies of World War II, Allied forces, or prosecuting civilians who engaged in such acts. In summary:

:...the assaults on crashed allied aviators were not typically acts of revenge for the bombing raids which immediately preceded them. [...] The perpetrators of these assaults were usually National Socialist officials, who did not hesitate to get their own hands dirty. The lynching murder in the sense of self-mobilizing communities or urban quarters was the exception.

Corporals killings, On March 19, 1988, two plain-clothes British soldiers drove straight towards a Provisional IRA funeral procession near Milltown Cemetery in Andersonstown, Belfast. The men were mistaken for Special Air Service members, surrounded by the crowd, dragged out, beaten, kicked, stabbed and eventually shot dead at a waste ground.

Lynching of members of the Turkish Armed Forces occurred in the aftermath of the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, 2016 Turkish ''coup d'état'' attempt.

In India, lynchings may reflect internal tensions between ethnic communities. Communities sometimes lynch individuals who are accused or suspected of committing crimes. Sociologists and social scientists reject attributing racial discrimination to the caste system and attributed such events to intra-racial ethno-cultural conflicts.

There have been numerous lynchings in relation to cow vigilante violence in India since 2014, mainly involving Hindu mobs lynching Indian Muslims. Some notable examples of such attacks include the 2015 Dadri mob lynching, the 2016 Jharkhand mob lynching, 2017 Alwar mob lynching. and the 2019 Jharkhand mob lynching. Mob lynching was reported for the third time in Alwar in July 2018, when a group of cow vigilantes killed a 31-year-old Muslim man named Rakbar Khan.

In 2006, four members of a Dalit family were slaughtered by Kunbi caste members in khairlanji, a village in the Bhandara district of Maharashtra.

In the 2015 Dimapur mob lynching, a mob in Dimapur, Nagaland, broke into a jail and lynched an accused Rape, rapist on March 5, 2015, while he was awaiting trial.

Since May 2017, when seven people were lynched in Jharkhand, India has experienced another spate of mob-related violence and killings known as the Indian WhatsApp lynchings following the spread of fake news, primarily relating to child-abduction and organ harvesting, via the WhatsApp message service.

In 2018 Junior civil aviation minister of India had garlanded and honored eight men who had been convicted in the lynching of trader Alimuddin Ansari in Ramgarh in June 2017 in a case of alleged cow vigilantism.

In June 2019, the Jharkhand mob lynching triggered widespread protests. The victim was a Muslim man named Tabrez Ansari lynching, Tabrez Ansari and was forced to chant Hindu slogans, including "''Jai Shri Ram''".

In July 2019, three men were beaten to death and lynched by mobs in Chhapra district of Bihar, on a minor case of theft of cattle.

Also in 2019, villagers in Jharkhand lynched four people on witchcraft suspicion, after Panchayati raj in India, panchayat decided that they were practicing black magic.

In September 2024, in Hayarna, five men were members of a cow vigilante group that murdered 24-year-old Sabir Malik from West Bengal.

In India, lynchings may reflect internal tensions between ethnic communities. Communities sometimes lynch individuals who are accused or suspected of committing crimes. Sociologists and social scientists reject attributing racial discrimination to the caste system and attributed such events to intra-racial ethno-cultural conflicts.

There have been numerous lynchings in relation to cow vigilante violence in India since 2014, mainly involving Hindu mobs lynching Indian Muslims. Some notable examples of such attacks include the 2015 Dadri mob lynching, the 2016 Jharkhand mob lynching, 2017 Alwar mob lynching. and the 2019 Jharkhand mob lynching. Mob lynching was reported for the third time in Alwar in July 2018, when a group of cow vigilantes killed a 31-year-old Muslim man named Rakbar Khan.

In 2006, four members of a Dalit family were slaughtered by Kunbi caste members in khairlanji, a village in the Bhandara district of Maharashtra.

In the 2015 Dimapur mob lynching, a mob in Dimapur, Nagaland, broke into a jail and lynched an accused Rape, rapist on March 5, 2015, while he was awaiting trial.

Since May 2017, when seven people were lynched in Jharkhand, India has experienced another spate of mob-related violence and killings known as the Indian WhatsApp lynchings following the spread of fake news, primarily relating to child-abduction and organ harvesting, via the WhatsApp message service.

In 2018 Junior civil aviation minister of India had garlanded and honored eight men who had been convicted in the lynching of trader Alimuddin Ansari in Ramgarh in June 2017 in a case of alleged cow vigilantism.

In June 2019, the Jharkhand mob lynching triggered widespread protests. The victim was a Muslim man named Tabrez Ansari lynching, Tabrez Ansari and was forced to chant Hindu slogans, including "''Jai Shri Ram''".

In July 2019, three men were beaten to death and lynched by mobs in Chhapra district of Bihar, on a minor case of theft of cattle.

Also in 2019, villagers in Jharkhand lynched four people on witchcraft suspicion, after Panchayati raj in India, panchayat decided that they were practicing black magic.

In September 2024, in Hayarna, five men were members of a cow vigilante group that murdered 24-year-old Sabir Malik from West Bengal.

online photographic survey of the history of lynchings in the United States

* Arellano, Lisa, ''Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Narratives of Community and Nation.'' Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012. * Bailey, Amy Kate and Stewart E. Tolnay. ''Lynched: The Victims of Southern Mob Violence.'' Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015. * Bakker, Laurens, Shaiel Ben-Ephraim, Nandana Dutta, Weiting Guo, Or Honig, Frank Jacob, Yogesh Raj, and Nicholas Rush Smith. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence: Volume 1: Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.'' University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Bancroft, H. H., ''Popular Tribunals'' (2 vols, San Francisco, 1887). * Beck, Elwood M. and Stewart E. Tolnay. "The killing fields of the deep south: the market for cotton and the lynching of blacks, 1882–1930." ''American Sociological Review'' (1990): 526–539.

online

* Manfred Berg, Berg, Manfred, ''Popular Justice: A History of Lynching in America''. Ivan R. Dee, Chicago 2011, . * Bernstein, Patricia, ''The First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP.'' College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press (March 2005), hardcover, * Brundage, W. Fitzhugh, ''Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930'', Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press (1993), * * Campney, Brent MS, Amy Chazkel, Stephen P. Frank, Dean J. Kotlowski, Gema Santamaría, Ryan Shaffer, and Hannah Skoda. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence: Volume 2: The Americas and Europe.'' University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Carrigan, William D., and Christopher Waldrep, eds. ''Swift to Wrath: Lynching in Global Historical Perspective'' (University of Virginia Press, 2013) * Crouch, Barry A. "A Spirit of Lawlessness: White violence, Texas Blacks, 1865–1868", ''Journal of Social History'' 18 (Winter 1984): 217–26. * Collins, Winfield

''The Truth about Lynching and the Negro in the South''

New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1918. * Cutler, James E., ''Lynch-Law: An Investigation Into the History of Lynching in the United States'' (New York, 1905) * Dray, Philip, ''At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America'', New York: Random House, 2002. * Eric Foner, ''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877''. 119–23. * Finley, Keith M., ''Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965'' (Baton Rouge, LSU Press, 2008). * Ginzburg, Ralph, ''100 Years Of Lynchings'', Black Classic Press (1962, 1988) softcover, * Hill, Karlos K. ''Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory.'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016. * Hill, Karlos K. "Black Vigilantism: The Rise and Decline of African American Lynch Mob Activity in the Mississippi and Arkansas Deltas, 1883–1923," ''Journal of African American History'', 95 no. 1 (Winter 2010): 26–43. * Ifill, Sherrilyn A., ''On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the 21st Century.'' Boston: Beacon Press (2007). * Jung, D., & Cohen, D. (2020). ''doi:10.1017/9781108885591, Lynching and Local Justice: Legitimacy and Accountability in Weak States''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * NAACP, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1918. New York City: Arno Press, 1919. * Nevels, Cynthia Skove, ''Lynching to Belong: claiming Whiteness though racial violence'', Texas A&M Press, 2007. * Pfeifer, Michael J., editor. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence : Volume 1: Asia, Africa, and the Middle East''. University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Pfeifer, Michael J., editor. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence: Volume 2: The Americas and Europe''. University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Pfeifer, Michael J. (ed.), ''Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South.'' Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013. * Robbins, Hollis ''The Literature of Lynching''

Chronicle of Higher Education

2015. * Rushdy, Ashraf H. A. ''American Lynching'' (Yale UP, 2012) * Rushdy, Ashraf H. A., ''The End of American Lynching.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012. * Seguin, Charles; Rigby, David, 2019, "National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941". ''Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World''. 5: 1–9. Doi (identifier), doi]

10.1177/2378023119841780

* Stagg, J. C. A., "The Problem of Klan Violence: The South Carolina Upcountry, 1868–1871," ''Journal of American Studies'' 8 (December 1974): 303–18. * Tolnay, Stewart E. and E. M. Beck, ''A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882–1930'', Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press (1995), * Trelease, Allen W., ''White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction'', Harper & Row, 1979. * Ida B. Wells, Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 1900, ''Mob Rule in New Orleans Robert Charles and His Fight to Death, the Story of His Life, Burning Human Beings Alive, Other Lynching Statistics'

Gutenberg eBook

* Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 1895, ''Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases'

Gutenberg eBook

* Wood, Amy Louise

"They Never Witnessed Such a Melodrama"

''Southern Spaces'', April 27, 2009. * Wood, Joe, ''Ugly Water'', St. Louis: Lulu, 2006. * Villanueva Jr., Nicholas. ''The Lynching of Mexicans in the Texas Borderlands.'' University of New Mexico Press, 2017 * Zangrando, Robert L. ''The NAACP crusade against lynching, 1909–1950'' (1980).

* Auslander, Mark

"Holding on to Those Who Can't be Held": Reenacting a Lynching at Moore's Ford, Georgia"

''Southern Spaces'', November 8, 2010. * Quinones, Sam

''True Tales From Another Mexico: the Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino and the Bronx''

(University of New Mexico Press): recounts a lynching in a small Mexican town in 1998. *

Gonzales-Day, Ken, ''Lynching in the West: 1850–1935''. Duke University Press, 2006.

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070625053440/http://users.bestweb.net/~rg/execution.htm ''Before the Needles, Executions (and Lynchings) in America Before Lethal Injection''. Details of thousands of lynchings]

Houghton Mifflin: The Reader's Companion to American History – Lynching

Lynching in Georgia

''New Georgia Encyclopedia''

a protest song about lynching, written by Abel Meeropol and recorded by Billie Holiday * ''Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture'' entry

Lynching in Arkansas

* Smith, Tom. ''The Crescent City Lynchings: The Murder of Chief Hennessy, the New Orleans 'Mafia' Trials, and the Parish Prison Mob''

crescentcitylynchings.com

* Nussio, Enzo; Clayton, Govinda (2024). "doi:10.1177/00223433231220275, Introducing the Lynching in Latin America (LYLA) dataset". ''Journal of Peace Research''. {{Discrimination Lynching, Attacks by method Corporal punishments Crowd psychology Extrajudicial killings by type Human rights abuses Racially motivated violence Religiously motivated violence Terrorism tactics Vigilantism

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle (often in the form of a hanging) for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in all societies.

Lynching in the United States, In the United States, where the word ''lynching'' likely originated, lynchings of African Americans became frequent in the Southern United States, South during the period after the Reconstruction era, especially during the nadir of American race relations.

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle (often in the form of a hanging) for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in all societies.

Lynching in the United States, In the United States, where the word ''lynching'' likely originated, lynchings of African Americans became frequent in the Southern United States, South during the period after the Reconstruction era, especially during the nadir of American race relations.

Etymology

The origins of the word ''lynch'' are obscure, but it likely originated during the American Revolution. The verb comes from the phrase ''Lynch Law'', a term for a Extrajudicial punishment, punishment without trial. Two Americans during this era are generally credited for coining the phrase: Charles Lynch (jurist), Charles Lynch (1736–1796) and William Lynch (Lynch law), William Lynch (1742–1820), both of whom lived in Virginia in the 1780s. Charles Lynch is more likely to have coined the phrase, as he was known to have used the term in 1782, while William Lynch is not known to have used the term until much later. There is no evidence that death was imposed as a punishment by either of the two men. In 1782, Charles Lynch wrote that his assistant had administered Lynch's law to Loyalist (American Revolution), Tories "for Dealing with the Black people, negroes Et cetera, &c". Charles Lynch was a Virginia Quakers, Quaker, Planter class, planter, and Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot who headed a county court in Virginia which imprisoned Loyalist (American Revolution), Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War, occasionally imprisoning them for up to a year. Although he lacked proper jurisdiction for detaining these persons, he claimed this right by arguing wartime necessity. Lynch was concerned that he might face legal action from one or more of those whom he had imprisoned, notwithstanding that the Patriots had won the war. In 1780, he persuaded the Continental Congress to pass Lynch's Law to forgive extrajudicial wartime Loyalist imprisonment. It was in connection with this that the term ''Lynch law'', meaning the assumption of extrajudicial authority, came into common parlance in the United States. Lynch was not accused of racist bias. He acquitted Black people accused of murder on three occasions.University of Chicago, ''Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary'' (1913 + 1828)He was accused, however, of ethnic prejudice in his handling of Welsh Americans, Welsh miners. William Lynch (Lynch law), William Lynch from Virginia claimed that the phrase was first used in a 1780 compact signed by him and his neighbors in Pittsylvania County. A 17th-century legend of James Lynch fitz Stephen, who was Mayor of Galway in Ireland in 1493, says that when his son was convicted of murder, the mayor hanged him from his own house. The story was proposed by 1904 as the origin of the word "lynch". It is dismissed by etymologists, both because of the distance in time and place from the alleged event to the word's later emergence, and because the incident did not constitute a lynching in the modern sense. The archaic verb ''linch'', to beat severely with a pliable instrument, to chastise or to maltreat, has been proposed as the etymological source; but there is no evidence that the word has survived into modern times, so this claim is also considered implausible. Since the 1970s, and especially since the 1990s, there has been a false etymology claiming that the word lynching comes from a fictitious William Lynch speech that was given by an especially brutal slaveholder to other slaveholders to explain how to control their slaves. Although a real person named William Lynch might have been the origin of the word lynching, the real life William Lynch definitely did not give this speech, and it is unknown whether the real William Lynch even owned slaves at all.

By country and region

Lynchings took place in many parts of the world over the centuries.United States

Lynchings took place in the United States both before and after the American Civil War, most commonly in Southern states and Western frontier settlements and most frequently in the late 19th century. They were often performed by self-appointed commissions, Ochlocracy, mobs, or vigilantes as a form of punishment for presumed criminal offenses. From 1883 to 1941 there were 4,467 victims of lynching. Of these, 4,027 were male, and 99 female. 341 were of unknown sex but are assumed to be likely male. In terms of ethnicity, 3,265 were black, 1,082 were white, 71 were Mexican or of Mexican descent, 38 were Native American, ten were Chinese, and one was Japanese. At the first recorded lynching, in St. Louis, Missouri, St. Louis in 1835, a Black man named McIntosh who killed a deputy sheriff while being taken to jail was captured, chained to a tree, and burned to death on a corner lot downtown in front of a crowd of over 1,000 people.

Universal suffrage indicated the beginning of mass lynching across southern United States. The rise to mobs of outrage such as the "red shirt" bands began to appear in many southern states at the time of when voting became a right for black men, a key historical turn of events that gave uprise to lynching. Initially intended as scare tactics, this outrage continues to grow more and more violent to the point of men being take from their homes, beaten, exiled, and even assassinated.

Mob violence arose as a means of enforcing White supremacy and frequently verged on systematic political terrorism. After the American Civil War, secret white supremacist terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, previously known as the "red-shirt bands", instigated extrajudicial assaults and killings due to a perceived loss of white power in America. Mobs usually alleged crimes for which they lynched Black people in order to instill fear. In the late 19th century, however, journalist Ida B. Wells showed that many presumed crimes were either exaggerated or had not even occurred. The magnitude of the extralegal violence which occurred during election campaigns, to prevent blacks from voting, reached epidemic proportions. The ideology behind lynching was directly connected to the denial of political and social equality, as stated forthrightly in 1900 by United States Senator and former governor of South Carolina Benjamin Tillman:

Members of mobs that participated in lynchings often took photographs of what they had done to their victims. Souvenir taking, such as the taking of pieces of rope, clothing, branches and sometimes Human trophy collecting, body parts was not uncommon. Some of those photographs were published and sold as lynching postcard, postcards.

Lynchings took place in the United States both before and after the American Civil War, most commonly in Southern states and Western frontier settlements and most frequently in the late 19th century. They were often performed by self-appointed commissions, Ochlocracy, mobs, or vigilantes as a form of punishment for presumed criminal offenses. From 1883 to 1941 there were 4,467 victims of lynching. Of these, 4,027 were male, and 99 female. 341 were of unknown sex but are assumed to be likely male. In terms of ethnicity, 3,265 were black, 1,082 were white, 71 were Mexican or of Mexican descent, 38 were Native American, ten were Chinese, and one was Japanese. At the first recorded lynching, in St. Louis, Missouri, St. Louis in 1835, a Black man named McIntosh who killed a deputy sheriff while being taken to jail was captured, chained to a tree, and burned to death on a corner lot downtown in front of a crowd of over 1,000 people.

Universal suffrage indicated the beginning of mass lynching across southern United States. The rise to mobs of outrage such as the "red shirt" bands began to appear in many southern states at the time of when voting became a right for black men, a key historical turn of events that gave uprise to lynching. Initially intended as scare tactics, this outrage continues to grow more and more violent to the point of men being take from their homes, beaten, exiled, and even assassinated.

Mob violence arose as a means of enforcing White supremacy and frequently verged on systematic political terrorism. After the American Civil War, secret white supremacist terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, previously known as the "red-shirt bands", instigated extrajudicial assaults and killings due to a perceived loss of white power in America. Mobs usually alleged crimes for which they lynched Black people in order to instill fear. In the late 19th century, however, journalist Ida B. Wells showed that many presumed crimes were either exaggerated or had not even occurred. The magnitude of the extralegal violence which occurred during election campaigns, to prevent blacks from voting, reached epidemic proportions. The ideology behind lynching was directly connected to the denial of political and social equality, as stated forthrightly in 1900 by United States Senator and former governor of South Carolina Benjamin Tillman:

Members of mobs that participated in lynchings often took photographs of what they had done to their victims. Souvenir taking, such as the taking of pieces of rope, clothing, branches and sometimes Human trophy collecting, body parts was not uncommon. Some of those photographs were published and sold as lynching postcard, postcards.

Anti-lynching legislation and the civil rights movement

The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill was first introduced to the United States Congress in 1918 by Republican Party (United States), Republican Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer of St. Louis, Missouri. The bill was passed by the United States House of Representatives in 1922, and in the same year it was given a favorable report by the United States Senate Committee. Its passage was blocked by White Democratic senators from the Solid South, the only representatives elected since the southern states Disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction Era, had disenfranchised African Americans around the start of the 20th century. The Dyer Bill influenced later anti-lynching legislation, including the Costigan-Wagner Bill, which was also defeated in the US Senate. The song "Strange Fruit" was composed by Abel Meeropol in 1937, inspired by the photograph of a lynching in Marion, Indiana. Meeropol said of the photograph, "It haunted me for days." It was published as a poem in the ''New York Teacher'' and later in the magazine ''New Masses'', in both cases under the pseudonym Lewis Allan. The poem was set to music, also by Meeropol, and the song was performed and popularized by Billie Holiday. The song has been performed by many other singers, including Nina Simone. By the 1950s, the civil rights movement was gaining new momentum. It was spurred by the lynching of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old youth from Chicago who was killed while visiting an uncle in Mississippi. His mother insisted on having an open-casket funeral so that people could see how badly her son had been beaten. The Black community throughout the U.S. became mobilized. Vann R. Newkirk wrote "the trial of his killers became a pageant illuminating the tyranny of white supremacy". The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were acquitted by an Racial discrimination in jury selection, all-white jury. David Jackson writes that it was the photograph of the "child's ravaged body, that forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism." Most lynchings ceased by the 1960s, but even in 2021 there were claims that racist lynchings still happen in the United States, being covered up as suicides. In 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice was opened in Montgomery, Alabama, a memorial that commemorates the victims of lynchings in the United States. On March 29, 2022, President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act of 2022 into law, which classified lynching as a federal hate crime.Europe

In Liverpool, a series of List of ethnic riots, race riots broke out in 1919 after the end of the World War I, First World War between White and Black sailors, many of whom had been demobilized. After a Black sailor had been stabbed by two White sailors in a pub for refusing to give them a cigarette, his friends attacked them the next day in revenge, wounding a policeman in the process. The Liverpool City Police, police responded by launching raids on lodging houses in primarily Black neighborhoods, with casualties on both sides. A White lynch mob gathered outside the houses during the raids and chased a Black sailor, Charles Wootton, into the River Mersey, Mersey River where he drowned. The Charles Wootton College in Liverpool has been named in his memory.

In 1944, Wolfgang Rosterg, a German prisoner of war known to be unsympathetic to the Nazi Germany, Nazi regime, was lynched by other German prisoners of war in Cultybraggan Camp, a prisoner-of-war camp in Comrie, Perth and Kinross, Comrie, Scotland. At the end of the World War II, Second World War, five of the perpetrators were Hanging, hanged at Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville Prison – the largest multiple execution in 20th-century Britain.

The situation is less clear with regards to reported "lynchings" in Germany. Propaganda in Nazi Germany, Nazi propaganda sometimes tried to depict state-sponsored violence as spontaneous lynchings. The most notorious instance of this was "Kristallnacht", which the government portrayed as the result of "popular wrath" against Jews, but it was carried out in an organized and planned manner, mainly by Sturmabteilung, SA and Schutzstaffel, SS men. Similarly, the approximately 150 confirmed murders of surviving crew members of crashed Allied aircraft in revenge for what Nazi propaganda called Strategic bombing during World War II, "Anglo-American bombing terror" were chiefly conducted by German officials and members of the police or the Gestapo, although civilians sometimes took part in them. The execution of enemy aircrew without trial in some cases had been ordered by Adolf Hitler, Hitler personally in May 1944. It was publicly announced that enemy pilots would no longer be protected from "public wrath". There were secret orders issued that prohibited policemen and soldiers from interfering in favor of the enemy in conflicts between civilians and Allies of World War II, Allied forces, or prosecuting civilians who engaged in such acts. In summary:

:...the assaults on crashed allied aviators were not typically acts of revenge for the bombing raids which immediately preceded them. [...] The perpetrators of these assaults were usually National Socialist officials, who did not hesitate to get their own hands dirty. The lynching murder in the sense of self-mobilizing communities or urban quarters was the exception.

Corporals killings, On March 19, 1988, two plain-clothes British soldiers drove straight towards a Provisional IRA funeral procession near Milltown Cemetery in Andersonstown, Belfast. The men were mistaken for Special Air Service members, surrounded by the crowd, dragged out, beaten, kicked, stabbed and eventually shot dead at a waste ground.

Lynching of members of the Turkish Armed Forces occurred in the aftermath of the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, 2016 Turkish ''coup d'état'' attempt.

In Liverpool, a series of List of ethnic riots, race riots broke out in 1919 after the end of the World War I, First World War between White and Black sailors, many of whom had been demobilized. After a Black sailor had been stabbed by two White sailors in a pub for refusing to give them a cigarette, his friends attacked them the next day in revenge, wounding a policeman in the process. The Liverpool City Police, police responded by launching raids on lodging houses in primarily Black neighborhoods, with casualties on both sides. A White lynch mob gathered outside the houses during the raids and chased a Black sailor, Charles Wootton, into the River Mersey, Mersey River where he drowned. The Charles Wootton College in Liverpool has been named in his memory.

In 1944, Wolfgang Rosterg, a German prisoner of war known to be unsympathetic to the Nazi Germany, Nazi regime, was lynched by other German prisoners of war in Cultybraggan Camp, a prisoner-of-war camp in Comrie, Perth and Kinross, Comrie, Scotland. At the end of the World War II, Second World War, five of the perpetrators were Hanging, hanged at Pentonville (HM Prison), Pentonville Prison – the largest multiple execution in 20th-century Britain.

The situation is less clear with regards to reported "lynchings" in Germany. Propaganda in Nazi Germany, Nazi propaganda sometimes tried to depict state-sponsored violence as spontaneous lynchings. The most notorious instance of this was "Kristallnacht", which the government portrayed as the result of "popular wrath" against Jews, but it was carried out in an organized and planned manner, mainly by Sturmabteilung, SA and Schutzstaffel, SS men. Similarly, the approximately 150 confirmed murders of surviving crew members of crashed Allied aircraft in revenge for what Nazi propaganda called Strategic bombing during World War II, "Anglo-American bombing terror" were chiefly conducted by German officials and members of the police or the Gestapo, although civilians sometimes took part in them. The execution of enemy aircrew without trial in some cases had been ordered by Adolf Hitler, Hitler personally in May 1944. It was publicly announced that enemy pilots would no longer be protected from "public wrath". There were secret orders issued that prohibited policemen and soldiers from interfering in favor of the enemy in conflicts between civilians and Allies of World War II, Allied forces, or prosecuting civilians who engaged in such acts. In summary:

:...the assaults on crashed allied aviators were not typically acts of revenge for the bombing raids which immediately preceded them. [...] The perpetrators of these assaults were usually National Socialist officials, who did not hesitate to get their own hands dirty. The lynching murder in the sense of self-mobilizing communities or urban quarters was the exception.

Corporals killings, On March 19, 1988, two plain-clothes British soldiers drove straight towards a Provisional IRA funeral procession near Milltown Cemetery in Andersonstown, Belfast. The men were mistaken for Special Air Service members, surrounded by the crowd, dragged out, beaten, kicked, stabbed and eventually shot dead at a waste ground.

Lynching of members of the Turkish Armed Forces occurred in the aftermath of the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, 2016 Turkish ''coup d'état'' attempt.

Latin America

Mexico

Lynchings have been present since the colonial period. Lynchings are a persistent form of extralegal violence in post-Revolutionary Mexico. A number of them have involved religious motivations. During and following the period of the Cristero War. On September 14, 1968, five employees from the Autonomous University of Puebla were lynched in the village of San Miguel Canoa, in the state of Puebla, after Enrique Meza Pérez, the local priest, incited the villagers to murder the employees, who he believed were communists. The five victims intended to enjoy their holiday climbing Malinche (volcano), La Malinche, a nearby mountain, but they had to stay in the village due to adverse weather conditions. Two of the employees, and the owner of the house where they were staying for the night, were killed; the three survivors sustained serious injuries, including finger amputations. The alleged main instigators were not prosecuted. The few arrested were released after no evidence was found against them. On November 23, 2004, in the 2004 Tláhuac lynching, Tláhuac lynching, three Mexican undercover federal agents investigating a narcotics-related crime were lynched in the town of Tláhuac, San Juan Ixtayopan (Mexico City) by an angry crowd who saw them taking photographs and suspected that they were trying to abduct children from a primary school. The agents immediately identified themselves, but they were held and beaten for several hours before two of them were killed and set on fire. The incident was covered by the media almost from the beginning, including their pleas for help and their murder. By the time police rescue units arrived, two of the agents were reduced to charred corpses and the third was seriously injured. Authorities suspect that the lynching was provoked by the persons who were being investigated. Both local and federal authorities had abandoned the agents, saying that the town was too far away for them to try to intervene. Some officials said they would provoke a massacre if the authorities tried to rescue the men from the mob.Brazil

According to ''The Wall Street Journal'', "Over the past 60 years, as many as 1.5 million Brazilians have taken part in lynchings...In Brazil, mobs now kill—or try to kill—more than one suspected lawbreaker a day, according to University of São Paulo sociologist José de Souza Martins, Brazil's leading expert on lynchings."Dominican Republic

Extrajudicial punishment, including lynching, of alleged criminals who committed various crimes, ranging from theft to murder, has some endorsement in Dominican society. According to a 2014 Latinobarómetro survey, the Dominican Republic had the highest rate of acceptance in Latin America of such unlawful measures. These issues are particularly evident in the Cibao, Northern Region.Haiti

After the 2010 Haiti earthquake, 2010 earthquake the slow distribution of relief supplies and the large number of affected people created concerns about Civil disorder, civil unrest, marked by looting and mob justice against suspected looters. In a 2010 news story, CNN reported, "At least 45 people, most of them Haitian Vodou, Vodou priests, have been lynched in Haiti since the beginning of the cholera epidemic by angry mobs blaming them for the spread of the disease, officials said.Africa

South Africa

The practice of whipping and necklacing offenders and political opponents evolved in the 1980s during the apartheid era in South Africa. Residents of Black townships formed "people's courts" and used whip lashings and deaths by necklacing in order to terrorize fellow Blacks who were seen as collaborators with the government. Necklacing is the torture and execution of a victim by igniting a kerosene-filled rubber tire that has been forced around the victim's chest and arms. Necklacing was used to punish victims who were alleged to be traitors to the Black liberation movement along with their relatives and associates. Sometimes the "people's courts" made mistakes, or they used the system to punish those whom the anti-Apartheid movement's leaders opposed. A tremendous controversy arose when the practice was endorsed by Winnie Mandela, then the wife of the then-imprisoned Nelson Mandela and a senior member of the African National Congress. In 1996, Rashaad Staggie was killed by a crowd of People Against Gangsterism and Drugs members. Kemp (2024) reports increasing, shockingly high numbers of mob justice murders—from 849 in April 2017-March 2018, to 1,202 in April 2019-March 2020, to 1,293 in 2021, to 1,849 in 2022, to 588 for January–March 2023. As Kemp summarizes, "In the 2017/18 financial year, there were approximately 2.3 mob justice murders every day in South Africa. In the 2021 calendar year, there were 3.4. And in 2022, that had increased to 5.2 – more than double the rate of five years ago."Nigeria

The practice of extrajudicial punishments, including lynching, is referred to as 'jungle justice' in Nigeria. The practice is widespread and "an established part of Nigerian society", predating the existence of the police. Exacted punishments vary between a "muddy treatment", that is, being made to roll in the mud for hours and severe beatings followed by necklacing. The case of the ''Aluu four lynching, Aluu four'' sparked national outrage. The absence of a functioning judicial system and law enforcement, coupled with corruption are blamed for the continuing existence of the practice.Kenya

There are frequent lynchings in Kenya. McKee (2024) is written largely with reference to a Kenya Lynchings Database that includes reports of over 3,100 lynched persons for Kenya for the years ca. 1980–2024. That number, however, is just a fraction of the total for that period, which may well exceed 10,000.Uganda

According to Ugandan news media, Uganda has had a continuing problem with lynchings from at least 2000. Example headlines with a smattering of contents, starting from 2000, include: 'Report Condemns Mob Justice' (Monitor, 2000); 'Rule of Jungle is Around the Corner' (Monitor, 2002, from which, "[Given the increasing level of robberies and murders in and around Kampala,] there is an increasing number [of people] who are taking the law in their hands. They are not just apprehending suspects, beating them up and handing them half-dead to the Police[; t]hey kill them, and in very dramatic and horrific fashion. They are impaling them on stakes, or tying them together if they are in a group and burning them up to name a few methods of choice"); 'Mob Justice Still a Serious Problem in Kampala,' (URN, 2006); 'Mob Justice Thrives' (The New Vision, 2007, from which, "A total of 197 people were killed in mob justice in Uganda last year alone, according to the 2006 Police crime report. Theft was the leading cause of lynching, accounting for 108 cases. Other victims were accused of robbery (14), witchcraft (13), murder (12), burglary (6) and other suspected crimes (31). Of the people lynched in 2006, 191 were male while six were female"); 'Mob Justice[: A] Problem That Just Won't Go Away' (The New Vision, 2009, including, "Since 2000, many people have been killed by mobs" ); 'Mob Justice in Uganda: A Troubling Issue' (NilePost, 2023, from which, "Mob justice in Uganda is a serious issue that requires our attention and concerted efforts to address the underlying problems. We must work together to create a Uganda where justice is achieved through a fair and equitable legal system, ensuring the rights and safety of all citizens"); "Deadly Consequences of Mob 'Justice'" (Monitor, 2025). Glad et al. (2010), in a Bachelor's final essay about Ugandan mob justice, summarize briefly, from among prior work on the subject, three Makerere University studies (Nalukenge 2001, Kanaabi 2004, Mutabazi 2006) and a journal article (Baker 2005). Parenthetically, another source on lynchings in Uganda, Mutabazi (2012), according to some of its early contents, appears to be (no more than) a tweaked-for-publication form of Mutabazi (2006). Mutabazi (2012) does not, e.g., refer to relevant (see in the previous paragraph) 2007 and 2008 lynching figures noted in Glad et al. (2010), but only to 244 and 273 reported cases of mob justice for 2001 and 2002, respectively; and, in its acknowledgments, Mutabazi refers to Mutabazi (2012) as "this dissertation" and has him thanking, among others, his supervisor and his course coordinator. Glad et al. (2010) also cite, from the Uganda Police's Crime Report 2008, 2007 and 2008 lynching figures of 184 and 368, respectively. They relate, from the report, that the 2008 figure is a 100% increase on the 2007 one; that there was nothing suggesting this "negative trend" was about to reverse itself; that the number of 2007 and 2008 lynchings were, to boot, surely under-reported; that "[t]he most common reasons for a mob to take the law into their own hands [were] theft, murder, robbery, witchcraft and burglary." They say, further, that the Ugandan media carried articles "almost daily regarding mob justice situations in different parts of the country and for different reasons"; that these articles "often tell the same stories about victims beaten or burned to death" for alleged offenses. The Uganda Police's Annual Crime Report 2010, for the years 2009 and 2010, has 'Death (by Mob Action)' victims numbering 364 and 438, respectively. The Uganda Police's Annual Crime Report 2019 says, "A total of 773 persons were lynched [in 2019], out of whom, 749 were male adults, 17 were female adults, 05 were male juveniles and 02 were female juveniles." The Uganda Police Force's Annual Crime Report 2024 appears to report 1,032 (not 1,078, per a mistake in the sum of a table's column) lynched persons from 1,016 reported cases of 'Murder by Mob Action'. One example case for 2025 is the lynching of police constable Suleiman Chemonges, at a burial service in Ibanda; another is the double-lynching of teenage brothers Paul Amukanga and Stanley Opidi, though several facts of the case differ for the time being, depending on which country's media reports it, whether Uganda's or Kenya's.Palestine and Israel

Palestinian lynch mobs have murdered Palestinians suspected of collaborating with Israel. According to a Human Rights Watch report from 2001: On October 12, 2000, the 2000 Ramallah lynching, Ramallah lynching took place. This happened at the el-Bireh police station, where a Palestinian people, Palestinian crowd killed and mutilated the bodies of two Israel Defense Forces reservists, Vadim Norzhich (Nurzhitz) and Yosef "Yossi" Avrahami, who had accidentally entered the Palestinian National Authority, Palestinian Authority-controlled city of Ramallah in the West Bank and were taken into custody by Palestinian Authority policemen. The Israeli reservists were beaten and stabbed. At this point, a Palestinian (later identified as Aziz Salha), appeared at the window, displaying his blood-soaked hands to the crowd, which erupted into cheers. The crowd clapped and cheered as one of the soldier's bodies was then thrown out the window and stamped and beaten by the frenzied crowd. One of the two was shot, set on fire, and his head beaten to a pulp. Soon after, the crowd dragged the two mutilated bodies to Al-Manara Square in the city center and began an impromptu victory celebration. Police officers proceeded to try and confiscate footage from reporters. On October 18, 2015, an Eritrean asylum seeker, Haftom Zarhum, was lynched by a mob of vengeful Israeli soldiers in Be'er Sheva's central bus station. Israeli security forces misidentified Haftom as the person who shot an Israeli police bus and shot him. Moments after, other security forces joined shooting Haftom when he was bleeding on the ground. Then, a soldier hit him with a bench nearby when two other soldiers approached the victim then forcefully kicked his head and upper body. Another soldier threw a bench over him to prevent his movement. At that moment a bystander pushed the bench away, but the security forces put back the chair and kicked the victim again and pushed the stopper away. Israeli medical forces did not evacuate the victim until eighteen minutes after the first shooting although the victim received 8 shots. In January 2016 four security forces were charged in connection with the lynching. The Israeli civilian who was involved in lynching the Eritrean civilian was sentenced to 100 days community service and 2,000 shekels. In August 2012, seven Israeli youths were arrested in Jerusalem for what several witnesses described as an attempted lynching of several Palestinian teenagers. The Palestinians received medical treatment and judicial support from Israeli facilities. In March 2025, Hamdan Ballal, a Palestinian co-director of the Oscar-winning documentary No Other Land, was beaten by Israeli settlers in the occupied West Bank before being detained by Israeli forces. According to his co-director Yuval Abraham and witnesses, the Israeli military stated it was investigating the incident.South Asia

India

In India, lynchings may reflect internal tensions between ethnic communities. Communities sometimes lynch individuals who are accused or suspected of committing crimes. Sociologists and social scientists reject attributing racial discrimination to the caste system and attributed such events to intra-racial ethno-cultural conflicts.

There have been numerous lynchings in relation to cow vigilante violence in India since 2014, mainly involving Hindu mobs lynching Indian Muslims. Some notable examples of such attacks include the 2015 Dadri mob lynching, the 2016 Jharkhand mob lynching, 2017 Alwar mob lynching. and the 2019 Jharkhand mob lynching. Mob lynching was reported for the third time in Alwar in July 2018, when a group of cow vigilantes killed a 31-year-old Muslim man named Rakbar Khan.

In 2006, four members of a Dalit family were slaughtered by Kunbi caste members in khairlanji, a village in the Bhandara district of Maharashtra.

In the 2015 Dimapur mob lynching, a mob in Dimapur, Nagaland, broke into a jail and lynched an accused Rape, rapist on March 5, 2015, while he was awaiting trial.

Since May 2017, when seven people were lynched in Jharkhand, India has experienced another spate of mob-related violence and killings known as the Indian WhatsApp lynchings following the spread of fake news, primarily relating to child-abduction and organ harvesting, via the WhatsApp message service.

In 2018 Junior civil aviation minister of India had garlanded and honored eight men who had been convicted in the lynching of trader Alimuddin Ansari in Ramgarh in June 2017 in a case of alleged cow vigilantism.

In June 2019, the Jharkhand mob lynching triggered widespread protests. The victim was a Muslim man named Tabrez Ansari lynching, Tabrez Ansari and was forced to chant Hindu slogans, including "''Jai Shri Ram''".

In July 2019, three men were beaten to death and lynched by mobs in Chhapra district of Bihar, on a minor case of theft of cattle.

Also in 2019, villagers in Jharkhand lynched four people on witchcraft suspicion, after Panchayati raj in India, panchayat decided that they were practicing black magic.

In September 2024, in Hayarna, five men were members of a cow vigilante group that murdered 24-year-old Sabir Malik from West Bengal.

In India, lynchings may reflect internal tensions between ethnic communities. Communities sometimes lynch individuals who are accused or suspected of committing crimes. Sociologists and social scientists reject attributing racial discrimination to the caste system and attributed such events to intra-racial ethno-cultural conflicts.

There have been numerous lynchings in relation to cow vigilante violence in India since 2014, mainly involving Hindu mobs lynching Indian Muslims. Some notable examples of such attacks include the 2015 Dadri mob lynching, the 2016 Jharkhand mob lynching, 2017 Alwar mob lynching. and the 2019 Jharkhand mob lynching. Mob lynching was reported for the third time in Alwar in July 2018, when a group of cow vigilantes killed a 31-year-old Muslim man named Rakbar Khan.

In 2006, four members of a Dalit family were slaughtered by Kunbi caste members in khairlanji, a village in the Bhandara district of Maharashtra.

In the 2015 Dimapur mob lynching, a mob in Dimapur, Nagaland, broke into a jail and lynched an accused Rape, rapist on March 5, 2015, while he was awaiting trial.

Since May 2017, when seven people were lynched in Jharkhand, India has experienced another spate of mob-related violence and killings known as the Indian WhatsApp lynchings following the spread of fake news, primarily relating to child-abduction and organ harvesting, via the WhatsApp message service.

In 2018 Junior civil aviation minister of India had garlanded and honored eight men who had been convicted in the lynching of trader Alimuddin Ansari in Ramgarh in June 2017 in a case of alleged cow vigilantism.

In June 2019, the Jharkhand mob lynching triggered widespread protests. The victim was a Muslim man named Tabrez Ansari lynching, Tabrez Ansari and was forced to chant Hindu slogans, including "''Jai Shri Ram''".

In July 2019, three men were beaten to death and lynched by mobs in Chhapra district of Bihar, on a minor case of theft of cattle.

Also in 2019, villagers in Jharkhand lynched four people on witchcraft suspicion, after Panchayati raj in India, panchayat decided that they were practicing black magic.

In September 2024, in Hayarna, five men were members of a cow vigilante group that murdered 24-year-old Sabir Malik from West Bengal.

Afghanistan

On March 19, 2015, in Kabul, Afghanistan a large crowd beat a young woman, Murder of Farkhunda Malikzada, Farkhunda, after she was accused by a local mullah of burning a copy of the Quran, Islam's holy book. Shortly afterwards, a crowd attacked her and beat her to death. They set the young woman's body on fire on the shore of the Kabul River. Although it was unclear whether the woman had burned the Quran, police officials and the clerics in the city defended the lynching, saying that the crowd had a right to defend their faith at all costs. They warned the government against taking action against those who had participated in the lynching. The event was filmed and shared on social media. The day after the incident six men were arrested on accusations of lynching, and Afghanistan's government promised to continue the investigation. On March 22, 2015, Farkhunda's burial was attended by a large crowd of Kabul residents; many demanded that she receive justice. A group of Afghan women carried her coffin, chanted slogans and demanded justice.Oceania

Papua New Guinea

A series of high-profile lynchings took place in Papua New Guinea in the late 1970s, in the period following independence. In September 1978, Morris Modeda, a 30-year-old man on trial for dangerous driving causing death, was lynched by a mob of 100 people near the town of Bereina. The lynching took place in front of William Prentice, the Chief Justice of Papua New Guinea, who had adjourned the trial to allow the court to view the site of the accident. Modeda was "battered to death with stones, sticks and a bushknife", while Prentice, his wife, and the court party – including barristers, court officials, witnesses and policemen – were "roughly handled but were not injured". Another prisoner was lynched in the same month in Kainantu while being escorted from a courthouse, receiving axe wounds in the head and chest. Days later, the police station at Banz in the Western Highlands Province, Western Highlands was raided by a mob which freed 50 prisoners and bludgeoned to death a man who had been involved in a fatal car accident. In 1979, Prentice and his fellow Supreme Court judges delivered the Special Report on the Developing State of Lawlessness to the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea. The report called on "urgent action to end police and prison staff inefficiency, ignorance and lack of discipline" and called for further support from traditional leaders.See also

* Frontier justice * Hate crime * Hate crime laws in the United States * Posse comitatus (common law), Posse * Racism ** Racism by country *** Racism against African Americans **** Racism in the United States ***** Black genocide in the United States – the notion that African Americans have been subjected to genocide throughout African-American history, their history because of Racism against African Americans, racism against them, an aspect of racism in the United States ***** Mass racial violence in the United States ***** Nadir of American race relations * Terrorism in the United States ** Domestic terrorism in the United States ** Timeline of terrorist attacks in the United States * VigilantismReferences

Further reading

* Allen, James (ed.), Hilton Als, John Lewis, and Leon F. Litwack, ''Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America'' (Twin Palms Pub: 2000), accompanied by aonline photographic survey of the history of lynchings in the United States

* Arellano, Lisa, ''Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Narratives of Community and Nation.'' Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012. * Bailey, Amy Kate and Stewart E. Tolnay. ''Lynched: The Victims of Southern Mob Violence.'' Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015. * Bakker, Laurens, Shaiel Ben-Ephraim, Nandana Dutta, Weiting Guo, Or Honig, Frank Jacob, Yogesh Raj, and Nicholas Rush Smith. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence: Volume 1: Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.'' University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Bancroft, H. H., ''Popular Tribunals'' (2 vols, San Francisco, 1887). * Beck, Elwood M. and Stewart E. Tolnay. "The killing fields of the deep south: the market for cotton and the lynching of blacks, 1882–1930." ''American Sociological Review'' (1990): 526–539.

online

* Manfred Berg, Berg, Manfred, ''Popular Justice: A History of Lynching in America''. Ivan R. Dee, Chicago 2011, . * Bernstein, Patricia, ''The First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP.'' College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press (March 2005), hardcover, * Brundage, W. Fitzhugh, ''Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930'', Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press (1993), * * Campney, Brent MS, Amy Chazkel, Stephen P. Frank, Dean J. Kotlowski, Gema Santamaría, Ryan Shaffer, and Hannah Skoda. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence: Volume 2: The Americas and Europe.'' University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Carrigan, William D., and Christopher Waldrep, eds. ''Swift to Wrath: Lynching in Global Historical Perspective'' (University of Virginia Press, 2013) * Crouch, Barry A. "A Spirit of Lawlessness: White violence, Texas Blacks, 1865–1868", ''Journal of Social History'' 18 (Winter 1984): 217–26. * Collins, Winfield

''The Truth about Lynching and the Negro in the South''

New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1918. * Cutler, James E., ''Lynch-Law: An Investigation Into the History of Lynching in the United States'' (New York, 1905) * Dray, Philip, ''At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America'', New York: Random House, 2002. * Eric Foner, ''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877''. 119–23. * Finley, Keith M., ''Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965'' (Baton Rouge, LSU Press, 2008). * Ginzburg, Ralph, ''100 Years Of Lynchings'', Black Classic Press (1962, 1988) softcover, * Hill, Karlos K. ''Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory.'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016. * Hill, Karlos K. "Black Vigilantism: The Rise and Decline of African American Lynch Mob Activity in the Mississippi and Arkansas Deltas, 1883–1923," ''Journal of African American History'', 95 no. 1 (Winter 2010): 26–43. * Ifill, Sherrilyn A., ''On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the 21st Century.'' Boston: Beacon Press (2007). * Jung, D., & Cohen, D. (2020). ''doi:10.1017/9781108885591, Lynching and Local Justice: Legitimacy and Accountability in Weak States''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * NAACP, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1918. New York City: Arno Press, 1919. * Nevels, Cynthia Skove, ''Lynching to Belong: claiming Whiteness though racial violence'', Texas A&M Press, 2007. * Pfeifer, Michael J., editor. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence : Volume 1: Asia, Africa, and the Middle East''. University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Pfeifer, Michael J., editor. ''Global Lynching and Collective Violence: Volume 2: The Americas and Europe''. University of Illinois Press, 2017. * Pfeifer, Michael J. (ed.), ''Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South.'' Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013. * Robbins, Hollis ''The Literature of Lynching''

Chronicle of Higher Education

2015. * Rushdy, Ashraf H. A. ''American Lynching'' (Yale UP, 2012) * Rushdy, Ashraf H. A., ''The End of American Lynching.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012. * Seguin, Charles; Rigby, David, 2019, "National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941". ''Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World''. 5: 1–9. Doi (identifier), doi]

10.1177/2378023119841780

* Stagg, J. C. A., "The Problem of Klan Violence: The South Carolina Upcountry, 1868–1871," ''Journal of American Studies'' 8 (December 1974): 303–18. * Tolnay, Stewart E. and E. M. Beck, ''A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882–1930'', Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press (1995), * Trelease, Allen W., ''White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction'', Harper & Row, 1979. * Ida B. Wells, Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 1900, ''Mob Rule in New Orleans Robert Charles and His Fight to Death, the Story of His Life, Burning Human Beings Alive, Other Lynching Statistics'

Gutenberg eBook

* Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 1895, ''Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases'

Gutenberg eBook

* Wood, Amy Louise

"They Never Witnessed Such a Melodrama"

''Southern Spaces'', April 27, 2009. * Wood, Joe, ''Ugly Water'', St. Louis: Lulu, 2006. * Villanueva Jr., Nicholas. ''The Lynching of Mexicans in the Texas Borderlands.'' University of New Mexico Press, 2017 * Zangrando, Robert L. ''The NAACP crusade against lynching, 1909–1950'' (1980).

External links

* Auslander, Mark

"Holding on to Those Who Can't be Held": Reenacting a Lynching at Moore's Ford, Georgia"

''Southern Spaces'', November 8, 2010. * Quinones, Sam

''True Tales From Another Mexico: the Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino and the Bronx''

(University of New Mexico Press): recounts a lynching in a small Mexican town in 1998. *

Gonzales-Day, Ken, ''Lynching in the West: 1850–1935''. Duke University Press, 2006.

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070625053440/http://users.bestweb.net/~rg/execution.htm ''Before the Needles, Executions (and Lynchings) in America Before Lethal Injection''. Details of thousands of lynchings]

Houghton Mifflin: The Reader's Companion to American History – Lynching

Lynching in Georgia

''New Georgia Encyclopedia''

a protest song about lynching, written by Abel Meeropol and recorded by Billie Holiday * ''Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture'' entry

Lynching in Arkansas

* Smith, Tom. ''The Crescent City Lynchings: The Murder of Chief Hennessy, the New Orleans 'Mafia' Trials, and the Parish Prison Mob''

crescentcitylynchings.com

* Nussio, Enzo; Clayton, Govinda (2024). "doi:10.1177/00223433231220275, Introducing the Lynching in Latin America (LYLA) dataset". ''Journal of Peace Research''. {{Discrimination Lynching, Attacks by method Corporal punishments Crowd psychology Extrajudicial killings by type Human rights abuses Racially motivated violence Religiously motivated violence Terrorism tactics Vigilantism