Mitterrand Doctrine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mitterrand doctrine ( French: ''Doctrine Mitterrand'') is a policy established in 1985 by French President

The Mitterrand doctrine ( French: ''Doctrine Mitterrand'') is a policy established in 1985 by French President

The list of Italians who benefited from the Mitterrand doctrine include:

*

The list of Italians who benefited from the Mitterrand doctrine include:

*

La France, l’Italie face à la question des extraditions – Institut François Mitterrand

* (texts by

Battisti se livre à la justice médiatique

''

Berlusconi, Chirac : deux hommes intègres face à Battisti

''Le Grand Soir'' *

'' Politis'', February 19, 2004 * {{in lang, fr}

Le fugitif raconte sa cavale dans un livre

'' La République des lettres'' Contemporary French history François Mitterrand French Fifth Republic Foreign policy doctrines History of the Italian Republic Years of Lead (Italy) Extradition France–Italy relations Far-left politics in France Political terminology in France

The Mitterrand doctrine ( French: ''Doctrine Mitterrand'') is a policy established in 1985 by French President

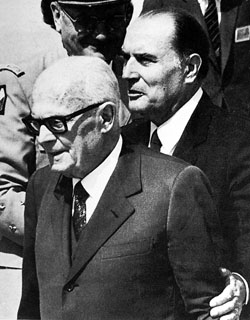

The Mitterrand doctrine ( French: ''Doctrine Mitterrand'') is a policy established in 1985 by French President François Mitterrand

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was a French politician and statesman who served as President of France from 1981 to 1995, the longest holder of that position in the history of France. As a former First ...

, of the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

, concerning Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

far-left terrorists who fled to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

: those convicted for violent acts in Italy, excluding "active, actual, bloody terrorism" during the " Years of Lead", would not be extradited

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdic ...

to Italy.

The Mitterrand Doctrine was softened in 2002, under the government of Jean-Pierre Raffarin

Jean-Pierre Raffarin (; born 3 August 1948) is a French politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 6 May 2002 to 31 May 2005 under President Jacques Chirac.

He resigned after France's rejection of the referendum on the European Un ...

during the presidency of Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, ; ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and 1986 to 1988, as well as Mayor of Pari ...

, when was extradited from France. However, it continued to remain in effect, with the extradition of 10 far-left terrorists from France to Italy blocked by the French Court of Cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case; they only interpret the relevant law. In this, they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In ...

in 2023.

Establishment

Mitterrand defined his doctrine during a speech at the ''Palais des sports'' inRennes

Rennes (; ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Resnn''; ) is a city in the east of Brittany in Northwestern France at the confluence of the rivers Ille and Vilaine. Rennes is the prefecture of the Brittany (administrative region), Brittany Regions of F ...

on February 1, 1985. Mitterrand excluded active terrorists from the protection. On 21 April 1985, at the 65th Congress of the Human Rights League (LDH), he declared that Italian criminals who had broken with their violent past and had fled to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

would be protected from extradition to Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

:

''"Italian refugees (...) who took part in terrorist action before 1981 (...) have broken links with the infernal machine in which they participated, have begun a second phase of their lives, have integrated into French society (...) I told the Italian government that they were safe from any sanction by the means of extradition"''.The policy statement was followed by French justice when it came to the extradition of far-left Italian terrorists or activists. According to a 2007 article by the ''

Corriere della Sera

(; ) is an Italian daily newspaper published in Milan with an average circulation of 246,278 copies in May 2023. First published on 5 March 1876, is one of Italy's oldest newspapers and is Italy's most read newspaper. Its masthead has remain ...

'', Mitterrand was convinced by Abbé Pierre

Abbé Pierre (born Henri Marie Joseph Grouès; 5 August 191222 January 2007) was a French Catholic priest. He was a member of the Resistance (France), Resistance during World War II and deputy of the Popular Republican Movement. In 1949, he foun ...

to protect those persons. According to Cesare Battisti's lawyers, Mitterrand had given his word in consultation with the Italian prime minister, the fellow socialist Bettino Craxi

Benedetto "Bettino" Craxi ( ; ; ; 24 February 1934 – 19 January 2000) was an Italian politician and statesman, leader of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) from 1976 to 1993, and the 45th Prime Minister of Italy, prime minister of Italy from 1 ...

.

In practice

The commitment long took the place of general policy of extradition of activists and Italian terrorists until it ceased to be in force after the extradition of Paolo Persichetti in 2002, a former member of theRed Brigades

The Red Brigades ( , often abbreviated BR) were an Italian far-left Marxist–Leninist militant group. It was responsible for numerous violent incidents during Italy's Years of Lead, including the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro in 1978, ...

, which was approved by the Raffarin government. The Cesare Battisti case, in particular, has provoked debate about the interpretation of the doctrine.

Opponents of the doctrine point out that what a president can say during his tenure is not a source of law and so the doctrine has no legal value. Proponents point out that it was nevertheless consistently applied until 2002 and consider that the former president had committed the country by his words.

Its supporters (intellectuals like Fred Vargas or Bernard-Henri Lévy

Bernard-Henri Georges Lévy (; ; born 5 November 1948) is a French public intellectual. Often referred to in France simply as BHL, he was one of the leaders of the " Nouveaux Philosophes" (New Philosophers) movement in 1976. His opinions, politi ...

, organizations such as the Greens The Greens or Greens may refer to:

Current political parties

*The Greens – The Green Alternative, Austria

*Australian Greens, also known as ''The Greens''

* Greens of Andorra

* The Greens (Benin)

*The Greens (Bulgaria)

* Greens of Bosnia and He ...

, the Human Rights League, , etc.), along with some personalities of the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

(PS), are opposed to noncompliance by the right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

in power with the Mitterrand doctrine.

The doctrine has been strongly criticized by the Italian Association of Victims of Terrorism (' or ''AIVITER''), which in 2008 expressed particular

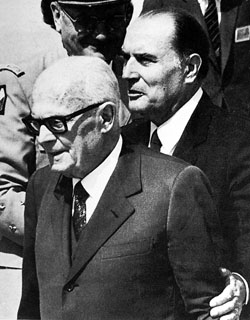

French President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, ; ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and 1986 to 1988, as well as Mayor of Pari ...

said that he would not oppose the extradition of persons wanted by the Italian courts.

Continuation

The Mitterrand doctrine was based on a supposed superiority of French law and its alleged greater adherence to European standards and principles concerning the protection of human rights. That vision entered in crisis, from a legal viewpoint, when theEuropean Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The court hears applications alleging that a co ...

(EHCR) finally ruled against the French procedure ''in absentia

''In Absentia'' is the seventh studio album by British progressive rock band Porcupine Tree, first released on 24 September 2002. The album marked several changes for the band, with it being the first with new drummer Gavin Harrison and the f ...

'', which is often used as a touchstone to consider the Italian procedure as being in fault. In its ruling, which breaks down to the root of French institutions, the ECHR decided that the so-called process of ''purgation in the absence'', the new trial after the arrest of the fugitive, is only a procedural device. The new process may therefore not be comparable to a guarantee for the prisoner that is given in France under Article 630 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the first trial in absentia is held without the presence of lawyers in explicit violation of the right to defence enshrined in Article 6, paragraph 3 letter c) of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is a supranational convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by the ...

(ECtHR: Krombach v. France, application no. 29731/96). Following this ruling, France partly amended its default procedure by the 9 March 2004 "Perben II" Act, untenable for European standards on human rights. The current procedure in the absence is defined as ''par défaut'' and allows for the defence by a lawyer.

In 2002, France extradited Paolo Persichetti, an ex-member of the communist terrorist group Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( , often abbreviated BR) were an Italian far-left Marxist–Leninist militant group. It was responsible for numerous violent incidents during Italy's Years of Lead, including the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro in 1978, ...

(BR) who was teaching sociology at the university, in breach of the Mitterrand doctrine. However, in 1998, Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

's appeal court

An appellate court, commonly called a court of appeal(s), appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear a case upon appeal from a trial court or other lower tribunal. Appellate ...

had judged that Sergio Tornaghi could not be extradited to Italy on the grounds that Italian procedure would not organise a second trial after the first trial ''in absentia''. The extraditions in the 2000s decade involved not only members of the Red Brigades but also other leftist activists who had fled to France and were being sought by Italian justice. They included Antonio Negri

Antonio Negri (; ; 1 August 1933 – 16 December 2023) was an Italian political philosopher known as one of the most prominent theorists of autonomism, as well as for his co-authorship of ''Empire (Hardt and Negri book), Empire'' with Michae ...

, who eventually chose to return to Italy and surrender to Italian authorities.

In 2004, French judicial officials authorised the extradition of Cesare Battisti. In 2005 the Conseil d'État

In France, the (; Council of State) is a governmental body that acts both as legal adviser to the executive branch and as the supreme court for administrative justice, which is one of the two branches of the French judiciary system. Establ ...

confirmed the extradition and softening the Mitterrand doctrine. Nonetheless Battisti had already fled to Mexico and subsequently to Brazil, where he lived as fugitive for the following 14 years. In 2018, when Brazil revoked his protection, he fled again to Bolivia and unsuccessfully sought asylum. He was arrested and extradited to Italy to expiate his sentence of life imprisonment for four murders.

In 2005, Gilles Martinet, an old socialist intellectual and former ambassador to Italy, wrote in the preface to a book that was dedicated to the Battisti case, "Not being able to make a revolution in our country, we continue to dream of it elsewhere. It continues to exist the need to prove ourselves that we are always on the left and that we have not departed from the ideal".

In 2021, 10 far-left Italian terrorists in France were arrested, with plans made to extradite them to Italy. The terrorists facing extradition were convicted of acts including murders and kidnappings. French authorities stated that their extradition would fall in line with the Mitterrand doctrine, as it did not necessarily apply to violent criminals. However, France's Court of Cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case; they only interpret the relevant law. In this, they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In ...

rejected the extradition attempt in 2023, allowing the 10 terrorists to remain within France.

As of 2021, Italy continued to seek the extradition of roughly 200 people residing in France.

The list of Italians who benefited from the Mitterrand doctrine include:

*

The list of Italians who benefited from the Mitterrand doctrine include:

*Toni Negri

Antonio Negri (; ; 1 August 1933 – 16 December 2023) was an Italian political philosopher known as one of the most prominent theorists of autonomism, as well as for his co-authorship of ''Empire (Hardt and Negri book), Empire'' with Michae ...

;

* Cesare Battisti, sentenced to life imprisonment for four murders;

*;

* Sergio Tornaghi;

* Oreste Scalzone;

* Marina Petrella;

* Franco Piperno;

* Lanfranco Pace;

*Enrico Villimburgo and Roberta Cappelli, sentenced to life imprisonment for murder;

*Giovanni Alimonti and Maurizio di Marzio, sentenced respectively to 22 and 15 years for a series of attacks;

*Enzo Calvitti, sentenced to 21 years for attempted murder;

*Vincenzo Spano, considered one of the leaders of the Organized Committees for the Liberation of the Proletariat;

*Massimo Carfora, who was sentenced to life imprisonment;

*Giovanni Vegliacasa, member of Prima Linea;

*Walter Grecchi, sentenced to 14 years for the murder of a police officer;

*Giorgio Pietrostefani Giorgio Pietrostefani (born 1943) was a leader of Lotta Continua. In 1988 the ''pentito'' accused him (along with Adriano Sofri) of ordering the 1972 murder of Luigi Calabresi

Luigi Calabresi (14 November 1937 – 17 May 1972) was an Italian '' ...

, sentenced to 22 years in prison along with Sofri and Bompressi for the murder of prosecutor Calabresi Calabresi is an Italian surname (meaning "Calabrese, Calabrian, from Calabria", plural masculine). Notable people with the surname include:

* Enrica Calabresi (1891–1944), Italian zoologist, herpetologist, and entomologist

* Guido Calabresi (born ...

;

* Simonetta Giorgieri and Carla Vendetti, suspected of contacts with the new Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( , often abbreviated BR) were an Italian far-left Marxist–Leninist militant group. It was responsible for numerous violent incidents during Italy's Years of Lead, including the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro in 1978, ...

, may also still be in France.

Reasons

The Mitterrand doctrine was supported by French intellectualsFor their ''refus de tout «sécuritarisme» autoritaire'' see ''In Memoriam'' Robert Paris, Cahiers Jaurès 2020/4 (N° 238), pages 147 à 153. on the alleged nonconformity of Italian legislation with European standards and, in the 21st century, the age of the fugitives. The French President opposed aspects of the anti-terrorist laws passed in Italy during the 1970s and the 1980s that created the status of ''collaboratore di giustizia"'' ("collaborators with justice" known commonly as ''pentito

''Pentito'' (; lit. "repentant"; plural: ''pentiti'') is used colloquially to designate collaborators of justice in Italian criminal procedure terminology who were formerly part of criminal organizations and decided to collaborate with a public ...

''), similar to the crown witness

A criminal turns state's evidence by admitting guilt and testifying as a witness for the state against their associate(s) or accomplice(s), often in exchange for leniency in sentencing or immunity from prosecution.Howard Abadinsky, ''Organized ...

legislation in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the Witness Protection Program

Witness protection is security provided to a threatened person providing testimonial evidence to the justice system, including defendants and other clients, before, during, and after trials, usually by police. While witnesses may only require p ...

in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in which people charged with crimes may become witnesses for the state and possibly receive reduced sentences and protection.

Italian legislation also provided that if a defendant can conduct his defence via his lawyers, trials held ''in absentia

''In Absentia'' is the seventh studio album by British progressive rock band Porcupine Tree, first released on 24 September 2002. The album marked several changes for the band, with it being the first with new drummer Gavin Harrison and the f ...

'' did not need to be repeated if he was eventually apprehended. The Italian ''in absentia'' procedure was upheld by the European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The court hears applications alleging that a co ...

(ECHR).

Film

* '' After the War'' (2017)See also

*History of the Italian Republic

The history of the Italian Republic concerns the events relating to the history of Italy that have occurred since 1946, when Italy became a republic after the 1946 Italian institutional referendum. The Italian republican history is generally div ...

*Strategy of tension

A strategy of tension () is a political policy where violent struggle is encouraged rather than suppressed. The purpose is to create a general feeling of insecurity in the population and make people seek security in a strong government.

The str ...

References

External links

*La France, l’Italie face à la question des extraditions – Institut François Mitterrand

* (texts by

Giorgio Agamben

Giorgio Agamben ( ; ; born 22 April 1942) is an Italian philosopher best known for his work investigating the concepts of the state of exception, form-of-life (borrowed from Ludwig Wittgenstein) and '' homo sacer''. The concept of biopolitic ...

, Paolo Persichetti, Oreste Scalzone, news articles, etc.)

*Battisti se livre à la justice médiatique

''

Le Figaro

() is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It was named after Figaro, a character in several plays by polymath Pierre Beaumarchais, Beaumarchais (1732–1799): ''Le Barbier de Séville'', ''The Guilty Mother, La Mère coupable'', ...

''

*Berlusconi, Chirac : deux hommes intègres face à Battisti

''Le Grand Soir'' *

'' Politis'', February 19, 2004 * {{in lang, fr}

Le fugitif raconte sa cavale dans un livre

'' La République des lettres'' Contemporary French history François Mitterrand French Fifth Republic Foreign policy doctrines History of the Italian Republic Years of Lead (Italy) Extradition France–Italy relations Far-left politics in France Political terminology in France