Mining In Roman Britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lead was essential to the smooth running of the Roman Empire.''Roman Britain: mining''

Lead was essential to the smooth running of the Roman Empire.''Roman Britain: mining''

/ref> It was used for

Gold was mined in Linlithgow (Scotland), Cornwall (England), the

Gold was mined in Linlithgow (Scotland), Cornwall (England), the

Many underground mines were constructed by the Romans. Once the raw ore was removed from the mine, it would be crushed, then washed. The less dense rock would wash away, leaving behind the

Some miners may have been slaves, but skilled artisans were needed for building aqueducts and

Some miners may have been slaves, but skilled artisans were needed for building aqueducts and

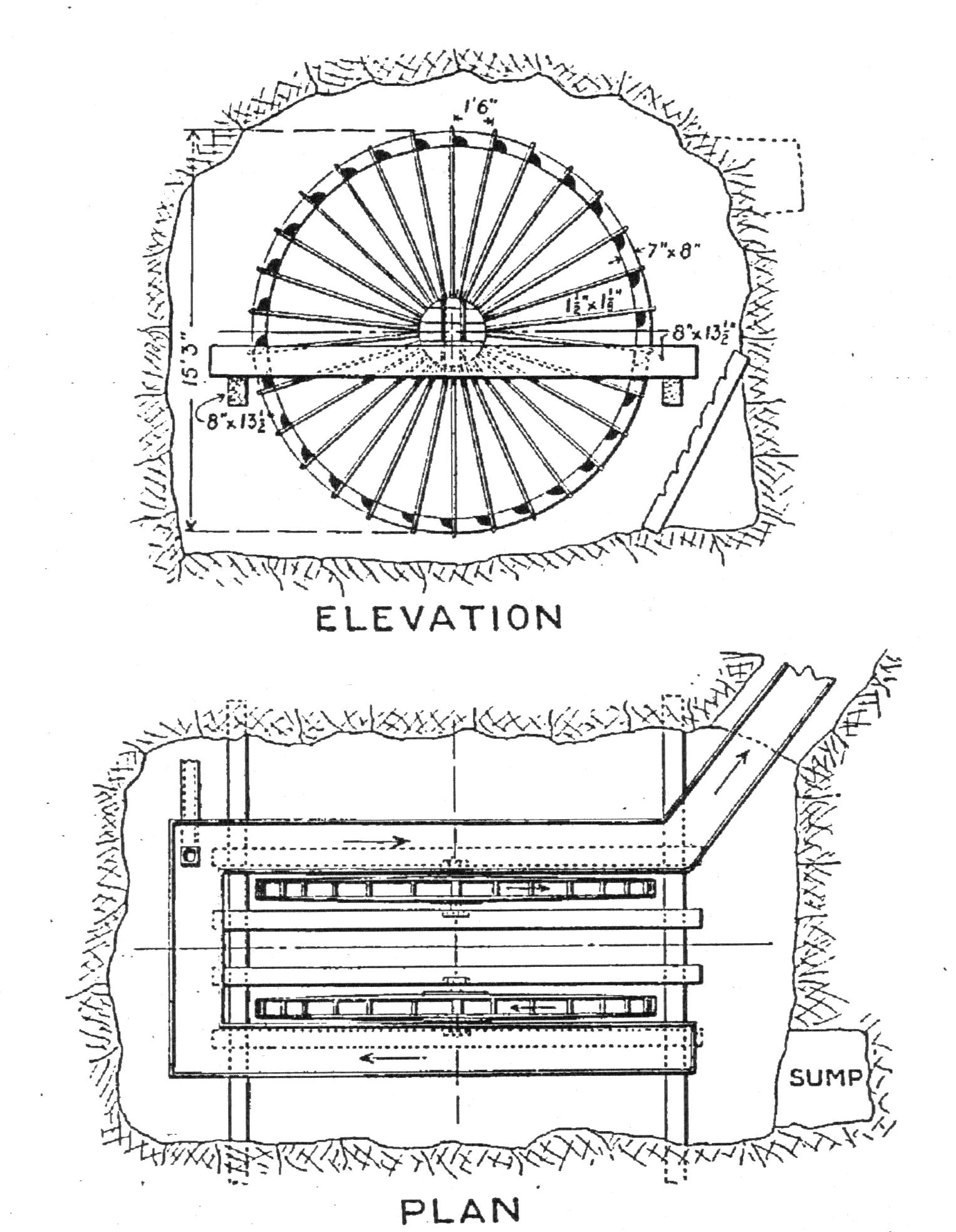

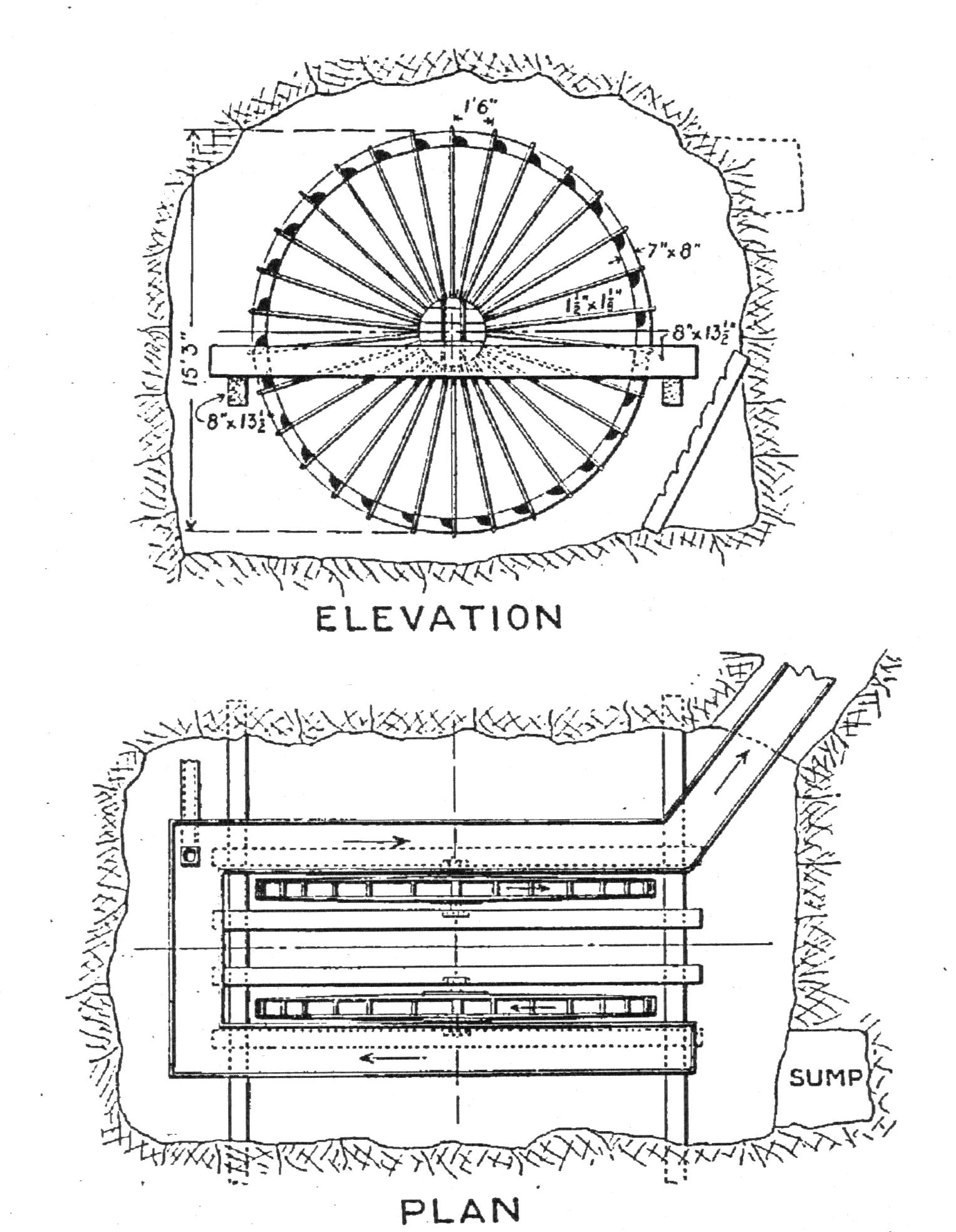

Animated water lifting wheel in a Roman gold mine

Oxford Roman Economy Project

*

Map of Mines

*

Mines Charts

Map of Roman Empire showing mines - Tabulae Geographicae

Roman Britain

Mining

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

was one of the most prosperous activities in Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caes ...

. Britain was rich in resources such as copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

, salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

, and tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

, materials in high demand in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. Sufficient supply of metals was needed to fulfil the demand for coinage and luxury artefacts by the elite. The Romans started panning and puddling for gold. The abundance of mineral resources in the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

was probably one of the reasons for the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain was the Roman Empire's conquest of most of the island of Great Britain, Britain, which was inhabited by the Celtic Britons. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the ...

. They were able to use advanced technology to find, develop and extract valuable minerals on a scale unequaled until the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

.

Tin mining

Tin mining in Britain has prehistoric roots, extraction and the alloying with copper being dated to c. 2000 BC. Tin ingots produced in Cornwall, during the second millennia BC, being found as far away as a shipwreck off the Israeli coast. The historic record of British tin extraction is credited to eitherHerodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, his Histories describing the Tin Islands, as does Hecataeus of Miletus

Hecataeus of Miletus (; ; c. 550 – c. 476 BC), son of Hegesander, was an early Greek historian and geographer.

Biography

Hailing from a very wealthy family, he lived in Miletus, then under Persian rule in the satrapy of Lydia ...

''Journey round the World'', both in the 5th century BC. The 4th century BC, Greek, Timaeus, also quoted by Pliny, and 1st century BC Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

and Posidonius

Posidonius (; , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greeks, Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher native to Apamea (Syria), Apame ...

all wrote on tin Mining in Cornwall and Devon

Mining in Cornwall and Devon, in the southwest of Britain, is thought to have begun in the early-middle Bronze Age with the exploitation of cassiterite. Tin, and later copper, were the most commonly extracted metals. Some tin mining continue ...

. Tin production is also offered as one of the primary factors for the 1st century CE Roman invasion, conquest, and occupation of Britannia, tin, lead, iron, silver, and gold extraction increasing throughout the Roman period.

Lead mining

/ref> It was used for

piping

Within industry, piping is a system of pipes used to convey fluids (liquids and gases) from one location to another. The engineering discipline of piping design studies the efficient transport of fluid.

Industrial process piping (and accomp ...

for aqueducts and plumbing

Plumbing is any system that conveys fluids for a wide range of applications. Plumbing uses piping, pipes, valves, piping and plumbing fitting, plumbing fixtures, Storage tank, tanks, and other apparatuses to convey fluids. HVAC, Heating and co ...

, pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85–99%), antimony (approximately 5–10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. In the past, it was an alloy of tin and lead, but most modern pewter, in order to prevent lead poi ...

, coffins, and gutters for villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

s, as well as a source of the silver that sometimes occurred in the same mineral deposits. Fifty-two sheets of Mendip lead still line the great bath at Bath which is a few miles from Charterhouse (see below).

The largest Roman lead mines were located in or near the Rio Tinto (river)

The Río Tinto (, ''wikt:tinto#Spanish, red river'' or Tinto River) is a highly toxic river in southwestern Spain that rises in the Sierra Morena mountains of Andalusia. It flows generally south-southwest, reaching the Gulf of Cádiz at Huelva. ...

in southern Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

. In Britannia the largest sources were at Mendip, South West England

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of the nine official regions of England, regions of England in the United Kingdom. Additionally, it is one of four regions that altogether make up Southern England. South West England con ...

and especially at Charterhouse. In A.D. 49, six years after the invasion and conquest of Britain, the Romans had the lead mines of Mendip and those of Derbyshire, Shropshire, Yorkshire and Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

running at full shift. By A.D.70, Britain had surpassed Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

as the leading lead-producing province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

. The Spanish soon lodged a complaint with the Emperor Vespasian, who in turn put limits on the amount of lead being produced in Britain. However British lead production continued to increase and ingots (or pigs) of lead have been found datable to the late second - early third century. Research has found that British lead (i.e. Somerset lead) was used in Pompeii - the town destroyed in the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D.79.

The Romans mined lead from the Mendips, Derbyshire, Durham, and Northumberland. The silver content of ores from these areas was significantly lower than Athenian lead-silver mines and Asia Minor mines.

Smelting is used to convert lead into its purest form. The extraction of lead occurs in a double decomposition reaction as the components of galena are decomposed to create lead. Sulfide is the reducing agent in this reaction, and fuel is only needed for high temperature maintenance. Lead must first be converted to its oxide form by roasting below 800C using domestic fire, charcoal or dry wood. This is done easily as lead melts at 327C. Lead oxide (PbO) is the oxide form of galena which reacts with the unroasted form lead sulfide (PbS) to form lead (Pb) and sulfur dioxide (SO2).

Details on Roman lead smelting have not been published even though open hearths were found in the Mendips by Rahtz and Boon. These remains contained smelted and unsmelted ores. The remains of first-century smelting were found in Pentre, Ffwrndan. Although this discovery was valuable, reconstruction of the remains were impossible due to damage. An extracted ore from the site had a lead content of 3 oz. (5 dwt) per ton and another piece contained 9 oz. (16 dwt) per ton of lead.

Silver extraction

The most important use of lead was the extraction of silver. Lead and silver were often found together in the form ofgalena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

, an abundant lead ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically including metals, concentrated above background levels, and that is economically viable to mine and process. The grade of ore refers to the concentration ...

. Galena is mined in the form of cubes and concentrated by removing the ore-bearing rocks. It is often recognized by its high density and dark colour. The Roman economy was based on silver, as the majority of higher value coins were minted from the precious metal. British ores found in Laurion, Greece had a low silver content compared to the ores mined from other locations. The Romans used the term 'British silver' for these lead mines.

The process of extraction, cupellation

Cupellation is a refining process in metallurgy in which ores or alloyed metals are treated under very high temperatures and subjected to controlled operations to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals, like lead, co ...

, was fairly simple. First, the ore was smelted until the lead, which contained the silver, separated from the rock. The lead was removed, and further heated up to 1100° Celsius

The degree Celsius is the unit of temperature on the Celsius temperature scale "Celsius temperature scale, also called centigrade temperature scale, scale based on 0 ° for the melting point of water and 100 ° for the boiling point ...

using hand bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

. At this point, the silver was separated from the lead (the lead, in the form of litharge

Litharge (from Greek , 'stone' + 'silver' ) is one of the natural mineral forms of lead(II) oxide, PbO. Litharge is a secondary mineral which forms from the oxidation of galena ores. It forms as coatings and encrustations with internal tetr ...

, was either blown off the molten surface or absorbed into bone ash crucibles; the litharge was re-smelted to recover the lead), and was put into moulds which, when cooled, would form ingots that were to be sent all over the Roman Empire for minting. Silchester, Wroxeter, and Hengisbury Head were known locations for Roman cupellation remains.

When inflation took hold in the third century A.D. and official coins began to be minted made of bronze with a silver wash, two counterfeit mints appeared in Somerset - one on the Polden Hills just south of the Mendips, and the other at Whitchurch, Bristol to the north. These mints, using Mendip silver, produced coins which were superior in silver content to those issued by the official Empire mints. Samples of these coins and of their moulds can be seen in the Museum of Somerset in Taunton Castle.

Copper mining

Copper alloy was mostly utilized in Roman Britain to make brooches, spoons, coins, statuettes and other things needed for armour. It was rarely used in it purest form; thus, it always contained other elements such as tin, zinc or lead, which added various properties to the alloy. Pure copper has a pinkish colour and, with the addition of a few percentage of other elements, its colour may change to pale brown, white or yellow. The composition of copper alloy differed from region to region in the Roman Empire. Leaded and unleaded bronze were mainly used in the Mediterranean period. These types of bronze were produced by adding tin and lead to copper in certain amounts that depended on the type of object being produced. 5% to 15% of tin was added to bronze for casting of most objects. Mirrors, on the other hand, were made with bronze that had approximately 20% tin as it needed a speculum, which is a silvery-white alloy. Another copper alloy, brass, was not widely used in casting objects as it was very difficult to produce. The production of brass did not begin until the development of the cementation process. In this process, zinc ore and pure copper are heated in a sealedcrucible

A crucible is a container in which metals or other substances may be melted or subjected to very high temperatures. Although crucibles have historically tended to be made out of clay, they can be made from any material that withstands temperat ...

. As the zinc ore is turned into zinc, the seal in the crucible traps the zinc vapour inside, which will then mix with the pure copper to produce brass. The production of brass through this process was controlled by 'state monopoly' as brass was being utilized for coins and military equipments. The production of ''sestertii

The ''sestertius'' (: ''sestertii'') or sesterce (: sesterces) was an ancient Roman coin. During the Roman Republic it was a small, silver coin issued only on rare occasions. During the Roman Empire it was a large brass coin.

The name ''sester ...

'' and '' dupondii'' from brass was established by the Augustan period and brass was also utilized in production of other military fittings such as '' lorica segmentata.''

Gold mining

Gold was mined in Linlithgow (Scotland), Cornwall (England), the

Gold was mined in Linlithgow (Scotland), Cornwall (England), the Dolaucothi Gold Mines

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines (; ) (), also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mines are located within the ...

(Wales), and other British Isles locations. Melting was necessary for this form of native silver as it is found in a form of leaves or filaments.

Britain's gold mines were located in Wales at Dolaucothi. The Romans discovered the Dolaucothi vein

Veins () are blood vessels in the circulatory system of humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are those of the pulmonary and feta ...

soon after their invasion, and they used hydraulic mining

Hydraulic mining is a form of mining that uses high-pressure jets of water to dislodge rock material or move sediment.Paul W. Thrush, ''A Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms'', US Bureau of Mines, 1968, p.560. In the placer mining of ...

methods to prospect the hillsides before discovering rich veins of gold-bearing quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock that was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tecton ...

. The remains of several aqueducts and water tanks above the mine are still visible today. The tanks were used to hold water for hushing during prospecting for veins, and involved releasing a wave of water to scour the ground and remove overburden, and expose the bedrock. If a vein was found, then it would be attacked using fire-setting, a method which involved building a fire against the rock. When the hot rock was quenched with water, it could be broken up easily, and the barren debris swept away using another wave of water. The technique produced numerous opencasts which are still visible in the hills above Pumsaint

Pumsaint is a village in Carmarthenshire, Wales, halfway between Llanwrda and Lampeter on the A482 in the valley of the Afon Cothi. It forms part of the extensive estate of Dolaucothi, which is owned by the National Trust.

The name is W ...

or Luentinum

Luentinum or Loventium refers to the Roman fort at Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire. The site lies either side of the A482 in Pumsaint and was in use from the mid 70s AD to around 120 AD. It may have had particular functions associated with the adjacen ...

today. A fort, settlement and bath-house were set up nearby in the Cothi Valley. The methods were probably used elsewhere for lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

and tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

mining, and indeed, were used widely before explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

made them redundant. Hydraulic mining

Hydraulic mining is a form of mining that uses high-pressure jets of water to dislodge rock material or move sediment.Paul W. Thrush, ''A Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms'', US Bureau of Mines, 1968, p.560. In the placer mining of ...

is however, still used for the extraction of alluvial tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

.

Long drainage adit

An adit (from Latin ''aditus'', entrance) or stulm

is a horizontal or nearly horizontal passage to an underground mine.

Miners can use adits for access, drainage, ventilation, and extracting minerals at the lowest convenient level. Adits are a ...

s were dug into one of the hills at Dolaucothi, after opencast mining methods were no longer effective. Once the ore was removed, it would be crushed by heavy hammers, probably automated by a water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous b ...

until reduced to a fine dust. Then, the dust would be washed in a stream of water where the rocks and other debris would be removed, the gold dust and flakes collected, and smelted into ingots

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of sh ...

. The ingots would be sent all across the Roman world, where they would be minted or put into vaults.

Iron mining

Armour, construction tools, agricultural tools, and other building materials were mostly made of iron; thus, making iron one of the most in demand metals at all times. There was always a supply for iron in many parts of the Roman Empire to allow for self sufficiency. There were many iron mines in Roman Britain. The index to the Ordnance Survey Map of Roman Britain lists 33 iron mines: 67% of these are in theWeald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, West Sussex, East Sussex, and Kent. It has three parts, the sandstone "High W ...

and 15% in the Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the Counties of England, county of Gloucestershire, England. It forms a roughly triangle, triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and no ...

. Because iron ores were widespread and iron was relatively cheap, the location of iron mines was often determined by the availability of wood, which Britain had in abundance, to make charcoal smelting fuel. Great amounts of iron were needed for the Roman war machine, and Britain was the perfect place to fill that need.Croydon Caving ClubMany underground mines were constructed by the Romans. Once the raw ore was removed from the mine, it would be crushed, then washed. The less dense rock would wash away, leaving behind the

iron oxide

An iron oxide is a chemical compound composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Ferric oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which is rust.

Iron ...

, which would then be smelted with the bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its iron oxides, oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called ...

method. Mixed with charcoal, the iron ore was heated in a low furnace below the melting point to avoid creating pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

, and to allow the reduced iron to agglomerate in a Play-Doh

Play-Doh, also known as Play-Dough, is a modeling compound for young children to make arts and crafts projects. The product was first manufactured in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States, as a wallpaper cleaner in the 1930s. Play-Doh was then rewor ...

like state. The slag

The general term slag may be a by-product or co-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and recycled metals depending on the type of material being produced. Slag is mainly a mixture of metal oxides and silicon dioxide. Broadly, it can be c ...

was taped out and disposed in very large quantities, allowing easy identification of the sites by archeologists, and sometimes used as road construction material. The extracted bloom iron was roughly hammered and probably sold as is to forges for further refining and use.

Roman iron was thought to hold more value than other metals due to the tedious production through direct or bloomery smelting. A recovered Vindolanda tablet documents the purchase of 90 Roman pounds of iron for 32 denarii by a man named Ascanius. This amounted to 1.1 denarii per kilogram of iron.

Coal

For both domestic and industrial use, coal provided a considerable proportion of the fuel required for warmth, metal-working (coal was not suitable for thesmelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron-making, iron, copper extraction, copper ...

of iron, but was more efficient than charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

at the forging

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compression (physics), compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die (manufacturing), die. Forging is often classif ...

stage) and the production of bricks, tiles and pottery. This is demonstrated by archaeological evidence from sites as far apart as Bath, Somerset

Bath (Received Pronunciation, RP: , ) is a city in Somerset, England, known for and named after its Roman Baths (Bath), Roman-built baths. At the 2021 census, the population was 94,092. Bath is in the valley of the River Avon, Bristol, River A ...

(the temple of Sulis and household hypocausts), military encampments along Hadrian's wall

Hadrian's Wall (, also known as the ''Roman Wall'', Picts' Wall, or ''Vallum Aelium'' in Latin) is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Roman Britain, Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian. Ru ...

(where outcrop coal was worked near the outlying fortlet at Moresby), forts of the Antonine Wall

The Antonine Wall () was a turf fortification on stone foundations, built by the Romans across what is now the Central Belt of Scotland, between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth. Built some twenty years after Hadrian's Wall to the south ...

, Carmel lead mines in north Wales and tile kilns at Holt, Clwyd

Clwyd ( , ) is a preserved counties of Wales, preserved county of Wales, situated in the north-east corner of the country; it is named after the River Clwyd, which runs through the area. To the north lies the Irish Sea, with the English cerem ...

. Excavations at the inland port of Heronbridge on the River Dee show that there was an established distribution network in place. Coal from the East Midlands

The East Midlands is one of nine official regions of England. It comprises the eastern half of the area traditionally known as the Midlands. It consists of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire (except for North Lincolnshire and North East ...

coalfields was carried along the Car Dyke

The Car Dyke was, and to a large extent still is, a long ditch which runs along the western edge of the Fens in eastern England for a distance of over . It is generally accepted as being a Roman invasion of Britain, Roman construction and was, f ...

for use in forges to the north of Duroliponte (Cambridge) and for drying grain from this rich cereal-growing region.

Extraction was not limited to open-cast exploitation of outcrops near the surface: shafts were dug and coal was hewn from horizontal galleries following the coal seams

Seam may refer to:

Science and technology

* Seam (geology), a stratum of coal or mineral that is economically viable; a bed or a distinct layer of vein of rock in other layers of rock

* Seam (metallurgy), a metalworking process the joins the ends ...

.Salt

In Britain, lead salt pans were used by the Romans at Middlewich, Nantwich and Northwich and excavations at Middlewich and Nantwich have revealed extensive salt-making settlements. Roman soldiers were partly paid in salt. It is said to be from this that we get the word soldier – 'sal dare', meaning to give salt. Salt would've also been used for food.Working conditions

Some miners may have been slaves, but skilled artisans were needed for building aqueducts and

Some miners may have been slaves, but skilled artisans were needed for building aqueducts and leat

A leat (; also lete or leet, or millstream) is the name, common in the south and west of England and in Wales, for an artificial watercourse or aqueduct dug into the ground, especially one supplying water to a watermill or its mill pond. Othe ...

s as well as the machinery needed to dewater mines and to crush and separate the ore from barren rock. Reverse overshot water-wheel

Frequently used in mines and probably elsewhere (such as agricultural drainage), the reverse overshot water wheel was a Roman innovation to help remove water from the lowest levels of underground workings. It is described by Vitruvius in his work ' ...

s were used to lift water, and sequences of such wheels have been found in the Spanish mines. A large section of a wheel from Rio Tinto can be seen in the British Museum, and a smaller fragment of a wheel found at Dolaucothi shows they used similar methods in Britain.

The working conditions were poor, especially when using fire-setting under ground, an ancient mining method used before explosives became common. It involved building a fire against a hard rock face, then quenching the hot rock with water, so that the thermal shock

Thermal shock is a phenomenon characterized by a rapid change in temperature that results in a transient mechanical load on an object. The load is caused by the differential expansion of different parts of the object due to the temperature chang ...

cracked the rock and allowed the minerals to be extracted. The method is described by Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

when he discussed the gold mines of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

in the first century BC, and at a much later date by Georg Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empire, he was broa ...

in his '' De Re Metallica'' of the 16th century. Every attempt was made to ventilate the deep mines, by driving many long adit

An adit (from Latin ''aditus'', entrance) or stulm

is a horizontal or nearly horizontal passage to an underground mine.

Miners can use adits for access, drainage, ventilation, and extracting minerals at the lowest convenient level. Adits are a ...

s for example, so as to ensure adequate air circulation. The same adits also served to drain the workings.

Fall of the metal economy

The Roman economy depended on the abundant metals that were mined in many regions. Approximately 100,000 tons of lead and 15,000 tons of copper were sourced within the imperial territory and about 2,250 tons of iron were produced each year. This abundance and extensive production of metal contributed to the pollution in Greenland ice, and it also affected the metal industry as more and more inexpensive metals were available throughout the empire. The production and availability of smelted metal started to cease during the late fourth century as the Romano-British economy began to decline. The only solution for people who needed metals as part of their livelihood was to scavenge for metal scraps. This is evident from the excavated metalworks from Southwark and Ickham. By the end of fourth century Britain was unable to sustain the need for metals, and so many metal-working sites were abandoned and skilled workers were left with no jobs.See also

* Mining in ancient Rome *Derbyshire lead mining history

This article details some of the history of lead mining in Derbyshire, England.

Background

Lutudarum (believed to have been at either Wirksworth or nearby Carsington) was the administrative centre of the Roman lead mining industry in Britain. ...

*Dolaucothi Gold Mines

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines (; ) (), also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mines are located within the ...

* Metal mining in Wales

*Roman engineering

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture ...

*Roman technology

Ancient Roman technology is the collection of techniques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the Roman economy, economy and Military of ancient Rome, milit ...

*Roman metallurgy

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia ...

Notes

References

* * *Elkington H.D.H.''The Mendip Lead Industry'' in Branigan K. and Fowler P.J. ''The Roman West Country'' (1976) *Elkington H.D.H. ''The Development of the Mining of Lead in the Iberian Peninsula and Britain under the Roman Empire''. Durham University Library (1968) *Jones G. D. B., I. J. Blakey, and E. C. F. MacPherson, ''Dolaucothi: the Roman aqueduct'', Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies 19 (1960): 71-84 and plates III-V. *Lewis, P. R. and G. D. B. Jones, ''The Dolaucothi gold mines, I: the surface evidence'', The Antiquaries Journal, 49, no. 2 (1969): 244–72. *Lewis, P. R. and G. D. B. Jones, ''Roman gold-mining in north-west Spain'', Journal of Roman Studies 60 (1970): 169–85. *Jones, R. F. J. and Bird, D. G., ''Roman gold-mining in north-west Spain, II: Workings on the Rio Duerna'', Journal of Roman Studies 62 (1972): 59–74. *Lewis, P. R., ''The Ogofau Roman gold mines at Dolaucothi'', The National Trust Year Book 1976-77 (1977). *Annels, A and Burnham, BC, ''The Dolaucothi Gold Mines'', University of Wales, Cardiff, 3rd Ed (1995). *Burnham, Barry C. "Roman Mining at Dolaucothi: the Implications of the 1991-3 Excavations near the Carreg Pumsaint", ''Britannia'' 28 (1997), 325-336 *Hodge, A.T. (2001). ''Roman Aqueducts & Water Supply'', 2nd ed. London: Duckworth. *Burnham, BC and H, ''Dolaucothi-Pumsaint: Survey and Excavation at a Roman Gold-mining complex (1987-1999)'', Oxbow Books (2004).Further reading

*Dark, K., and P. Dark. ''The landscape of Roman Britain''. Stroud: Sutton, 1997. *Jones, B., and D. Mattingly. ''An atlas of Roman Britain''. Oxford: Oxbow, 2002. *Reece, R. ''The coinage of Roman Britain''. Stroud: Tempus, 2002. *Schrüfer-Kolb, Irene. ''Roman Iron Production In Britain: Technological and Socio-Economic Landscape Development Along the Jurassic Ridge''. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2004. *Sim, D., and I. Ridge. ''Iron for the eagles: The iron industry of Roman Britain''. Stroud: Tempus, 2002.External links

{{Library resources box , by=no , onlinebooks=yes , others=yes , about=yes , label=Mining in Roman Britain , viaf= , lccn= , lcheading= , wikititle=Animated water lifting wheel in a Roman gold mine

Oxford Roman Economy Project

*

Map of Mines

*

Mines Charts

Map of Roman Empire showing mines - Tabulae Geographicae

Roman Britain

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

Industry in ancient Rome