minerals on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

Minerals

'; p. 1. In the series ''Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks''. Rosen Publishing Group. The

Optical mineralogy

', 2nd ed., p. 374. McGraw-Hill; . . If a chemical compound occurs naturally with different crystal structures, each structure is considered a different mineral species. Thus, for example,

A rock is an aggregate of one or more minerals, pp. 15–16 or mineraloids. Some rocks, such as

A rock is an aggregate of one or more minerals, pp. 15–16 or mineraloids. Some rocks, such as

" entry in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Accessed on 2020-08-28. The word "species" comes from the Latin ''species'', "a particular sort, kind, or type with distinct look, or appearance".

The abundance and diversity of minerals is controlled directly by their chemistry, in turn dependent on elemental abundances in the Earth. The majority of minerals observed are derived from the

The abundance and diversity of minerals is controlled directly by their chemistry, in turn dependent on elemental abundances in the Earth. The majority of minerals observed are derived from the

geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid

Solid is a state of matter where molecules are closely packed and can not slide past each other. Solids resist compression, expansion, or external forces that would alter its shape, with the degree to which they are resisted dependent upon the ...

substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat ...

that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Minerals

'; p. 1. In the series ''Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks''. Rosen Publishing Group. The

geological

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth s ...

definition of mineral normally excludes compounds that occur only in living organisms. However, some minerals are often biogenic

A biogenic substance is a product made by or of life forms. While the term originally was specific to metabolite compounds that had toxic effects on other organisms, it has developed to encompass any constituents, secretions, and metabolites of p ...

(such as calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

) or organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s in the sense of chemistry (such as mellite). Moreover, living organisms often synthesize inorganic minerals (such as hydroxylapatite) that also occur in rocks.

The concept of mineral is distinct from rock, which is any bulk solid geologic material that is relatively homogeneous at a large enough scale. A rock may consist of one type of mineral or may be an aggregate of two or more different types of minerals, spacially segregated into distinct phases.

Some natural solid substances without a definite crystalline structure, such as opal

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silicon dioxide, silica (SiO2·''n''H2O); its water content may range from 3% to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6% and 10%. Due to the amorphous (chemical) physical structure, it is classified as a ...

or obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

, are more properly called mineraloid

A mineraloid is a naturally occurring substance that resembles a mineral, but does not demonstrate the crystallinity of a mineral. Mineraloid substances possess chemical compositions that vary beyond the generally accepted ranges for specific mi ...

s.Austin Flint Rogers and Paul Francis Kerr (1942): Optical mineralogy

', 2nd ed., p. 374. McGraw-Hill; . . If a chemical compound occurs naturally with different crystal structures, each structure is considered a different mineral species. Thus, for example,

quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

and stishovite are two different minerals consisting of the same compound, silicon dioxide

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundan ...

.

The International Mineralogical Association

Founded in 1958, the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) is an international group of 40 national societies. The goal is to promote the science of mineralogy and to standardize the nomenclature of the 5000 plus known mineral species. ...

(IMA) is the generally recognized standard body for the definition and nomenclature of mineral species. , the IMA recognizes 6,145 official mineral species.

The chemical composition of a named mineral species may vary somewhat due to the inclusion of small amounts of impurities. Specific varieties of a species sometimes have conventional or official names of their own. For example, amethyst

Amethyst is a Violet (color), violet variety of quartz. The name comes from the Koine Greek from - , "not" and (Ancient Greek) / (Modern Greek), "intoxicate", a reference to the belief that the stone protected its owner from Alcohol into ...

is a purple variety of the mineral species quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

. Some mineral species can have variable proportions of two or more chemical elements

A chemical element is a chemical substance whose atoms all have the same number of protons. The number of protons is called the atomic number of that element. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8: each oxygen atom has 8 protons in i ...

that occupy equivalent positions in the mineral's structure; for example, the formula of mackinawite

Mackinawite is an iron nickel sulfide mineral with the chemical formula (where x = 0 to 0.11). The mineral crystallizes in the tetragonal crystal system and has been described as a distorted, close packed, cubic array of S atoms with some of t ...

is given as , meaning , where ''x'' is a variable number between 0 and 9. Sometimes a mineral with variable composition is split into separate species, more or less arbitrarily, forming a mineral group

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral group is a set of mineral species with essentially the same crystal structure and composed of chemically similar elements.Stuart J. Mills, Frédéric Hatert, Ernest H. Nickel, and Giovanni Ferraris (2009): "The ...

; that is the case of the silicates , the olivine group.

Besides the essential chemical composition and crystal structure, the description of a mineral species usually includes its common physical properties such as habit, hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to plastic deformation, such as an indentation (over an area) or a scratch (linear), induced mechanically either by Pressing (metalworking), pressing or abrasion ...

, lustre, diaphaneity, colour, streak, tenacity, cleavage, fracture

Fracture is the appearance of a crack or complete separation of an object or material into two or more pieces under the action of stress (mechanics), stress. The fracture of a solid usually occurs due to the development of certain displacemen ...

, system

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its open system (systems theory), environment, is described by its boundaries, str ...

, zoning, parting, specific gravity, magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

, fluorescence

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with colore ...

, radioactivity

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

, as well as its taste or smell and its reaction to acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

.

Minerals are classified by key chemical constituents; the two dominant systems are the Dana classification and the Strunz classification. Silicate mineral

Silicate minerals are rock-forming minerals made up of silicate groups. They are the largest and most important class of minerals and make up approximately 90 percent of Earth's crust.

In mineralogy, the crystalline forms of silica (silicon dio ...

s comprise approximately 90% of the Earth's crust

Earth's crust is its thick outer shell of rock, referring to less than one percent of the planet's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a solidified division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper ...

. Other important mineral groups include the native elements (made up of a single pure element) and compounds (combinations of multiple elements) namely sulfides (e.g. Galena ''PbS''), oxides (e.g. quartz ''SiO2''), halides (e.g. rock salt ''NaCl''), carbonates (e.g. calcite ''CaCO3''), sulfates

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a Polyatomic ion, polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salt (chemistry), ...

(e.g. gypsum ''CaSO4·2H2O''), silicates

A silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is also used for an ...

(e.g. orthoclase ''KAlSi3O8''), molybdates (e.g. wulfenite ''PbMoO4'') and phosphates (e.g. pyromorphite ''Pb5(PO4)3Cl'').

Definitions

International Mineralogical Association

TheInternational Mineralogical Association

Founded in 1958, the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) is an international group of 40 national societies. The goal is to promote the science of mineralogy and to standardize the nomenclature of the 5000 plus known mineral species. ...

has established the following requirements for a substance to be considered a distinct mineral:E. H. Nickel & J. D. Grice (1998): "The IMA Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names: procedures and guidelines on mineral nomenclature". ''Mineralogy and Petrology'', volume 64, issue 1, pages 237–263.

# ''It must be a naturally occurring substance formed by natural geological processes'', on Earth or other extraterrestrial bodies. This excludes compounds directly and exclusively generated by human activities (anthropogenic

Anthropogenic ("human" + "generating") is an adjective that may refer to:

* Anthropogeny, the study of the origins of humanity

Anthropogenic may also refer to things that have been generated by humans, as follows:

* Human impact on the enviro ...

) or in living beings (biogenic

A biogenic substance is a product made by or of life forms. While the term originally was specific to metabolite compounds that had toxic effects on other organisms, it has developed to encompass any constituents, secretions, and metabolites of p ...

), such as tungsten carbide, urinary calculi, calcium oxalate crystals in plant tissues, and seashells. However, substances with such origins may qualify if geological processes were involved in their genesis (as is the case of evenkite, derived from plant material; or taranakite, from bat guano; or alpersite, from mine tailings). Hypothetical substances are also excluded, even if they are predicted to occur in inaccessible natural environments like the Earth's core or other planets.

# ''It must be a solid substance in its natural occurrence.'' A major exception to this rule is native mercury: it is still classified as a mineral by the IMA, even though crystallizes only below −39 °C, because it was included before the current rules were established. Water and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

are not considered minerals, even though they are often found as inclusions in other minerals; but water ice is considered a mineral.

# ''It must have a well-defined crystallographic structure''; or, more generally, an ordered atomic arrangement. This property implies several macroscopic

The macroscopic scale is the length scale on which objects or phenomena are large enough to be visible with the naked eye, without magnifying optical instruments. It is the opposite of microscopic.

Overview

When applied to physical phenome ...

physical properties, such as crystal form, hardness, and cleavage., pp. 13–14 It excludes ozokerite, limonite

Limonite () is an iron ore consisting of a mixture of hydrated iron(III) oxide-hydroxides in varying composition. The generic formula is frequently written as , although this is not entirely accurate as the ratio of oxide to hydroxide can vary qu ...

, obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

and many other amorphous (non-crystalline) materials that occur in geologic contexts.

# ''It must have a fairly well defined chemical composition''. However, certain crystalline substances with a fixed structure but variable composition may be considered single mineral species. A common class of examples are solid solution

A solid solution, a term popularly used for metals, is a homogeneous mixture of two compounds in solid state and having a single crystal structure. Many examples can be found in metallurgy, geology, and solid-state chemistry. The word "solutio ...

s such as mackinawite

Mackinawite is an iron nickel sulfide mineral with the chemical formula (where x = 0 to 0.11). The mineral crystallizes in the tetragonal crystal system and has been described as a distorted, close packed, cubic array of S atoms with some of t ...

, (Fe, Ni)9S8, which is mostly a ferrous

In chemistry, iron(II) refers to the chemical element, element iron in its +2 oxidation number, oxidation state. The adjective ''ferrous'' or the prefix ''ferro-'' is often used to specify such compounds, as in ''ferrous chloride'' for iron(II ...

sulfide with a significant fraction of iron atoms replaced by nickel atoms. Other examples include layered crystals with variable layer stacking, or crystals that differ only in the regular arrangement of vacancies and substitutions. On the other hand, some substances that have a continuous series of compositions, may be arbitrarily split into several minerals. The typical example is the olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron Silicate minerals, silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of Nesosilicates, nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle, it is a com ...

group (Mg, Fe)2SiO4, whose magnesium-rich and iron-rich end-members are considered separate minerals ( forsterite and fayalite

Fayalite (, commonly abbreviated to Fa) is the iron-rich endmember, end-member of the olivine solid solution, solid-solution series. In common with all minerals in the olivine, olivine group, fayalite crystallizes in the orthorhombic system (spac ...

).

The details of these rules are somewhat controversial. For instance, there have been several recent proposals to classify amorphous substances as minerals, but they have not been accepted by the IMA.

The IMA is also reluctant to accept minerals that occur naturally only in the form of nanoparticle

A nanoparticle or ultrafine particle is a particle of matter 1 to 100 nanometres (nm) in diameter. The term is sometimes used for larger particles, up to 500 nm, or fibers and tubes that are less than 100 nm in only two directions. At ...

s a few hundred atoms across, but has not defined a minimum crystal size.

Some authors require the material to be a stable or metastable solid at room temperature (25 °C). However, the IMA only requires that the substance be stable enough for its structure and composition to be well-determined. For example, it recognizes meridianiite (a naturally occurring hydrate of magnesium sulfate

Magnesium sulfate or magnesium sulphate is a chemical compound, a salt with the formula , consisting of magnesium cations (20.19% by mass) and sulfate anions . It is a white crystalline solid, soluble in water but not in ethanol.

Magnesi ...

) as a mineral, even though it is formed and stable only below 2 °C.

, 6,145 mineral species are approved by the IMA. They are most commonly named after a person, followed by discovery location; names based on chemical composition or physical properties are the two other major groups of mineral name etymologies. Most names end in "-ite"; the exceptions are usually names that were well-established before the organization of mineralogy as a discipline, for example galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

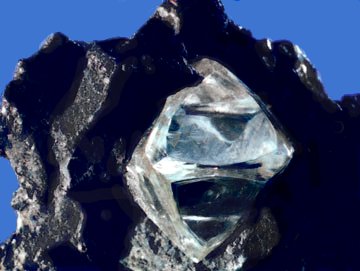

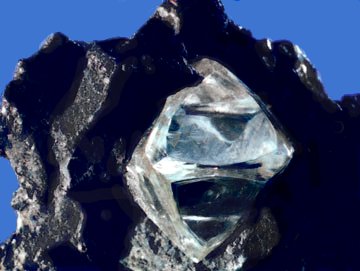

and diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

.

Biogenic minerals

A topic of contention among geologists and mineralogists has been the IMA's decision to exclude biogenic crystalline substances. For example, Lowenstam (1981) stated that "organisms are capable of forming a diverse array of minerals, some of which cannot be formed inorganically in the biosphere." Skinner (2005) views all solids as potential minerals and includes biominerals in the mineral kingdom, which are those that are created by the metabolic activities of organisms. Skinner expanded the previous definition of a mineral to classify "element or compound, amorphous or crystalline, formed through '' biogeochemical '' processes," as a mineral. Recent advances in high-resolutiongenetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

and X-ray absorption spectroscopy are providing revelations on the biogeochemical relations between microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s and minerals that may shed new light on this question. For example, the IMA-commissioned "Working Group on Environmental Mineralogy and Geochemistry " deals with minerals in the hydrosphere

The hydrosphere () is the combined mass of water found on, under, and above the Planetary surface, surface of a planet, minor planet, or natural satellite. Although Earth's hydrosphere has been around for about 4 billion years, it continues to ch ...

, atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

, and biosphere

The biosphere (), also called the ecosphere (), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be termed the zone of life on the Earth. The biosphere (which is technically a spherical shell) is virtually a closed system with regard to mat ...

. The group's scope includes mineral-forming microorganisms, which exist on nearly every rock, soil, and particle surface spanning the globe to depths of at least 1600 metres below the sea floor and 70 kilometres into the stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second-lowest layer of the atmosphere of Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is composed of stratified temperature zones, with the warmer layers of air located higher ...

(possibly entering the mesosphere).

Biogeochemical cycle

A biogeochemical cycle, or more generally a cycle of matter, is the movement and transformation of chemical elements and compounds between living organisms, the atmosphere, and the Earth's crust. Major biogeochemical cycles include the carbon cyc ...

s have contributed to the formation of minerals for billions of years. Microorganisms can precipitate metals from solution, contributing to the formation of ore deposits. They can also catalyze the dissolution of minerals.

Prior to the International Mineralogical Association's listing, over 60 biominerals had been discovered, named, and published. These minerals (a sub-set tabulated in Lowenstam (1981)) are considered minerals proper according to Skinner's (2005) definition. These biominerals are not listed in the International Mineral Association official list of mineral names; however, many of these biomineral representatives are distributed amongst the 78 mineral classes listed in the Dana classification scheme.

Skinner's (2005) definition of a mineral takes this matter into account by stating that a mineral can be crystalline or amorphous. Although biominerals are not the most common form of minerals, they help to define the limits of what constitutes a mineral proper. Nickel's (1995) formal definition explicitly mentioned crystallinity as a key to defining a substance as a mineral. A 2011 article defined icosahedrite

Icosahedrite is the first known naturally occurring quasicrystal Phase (matter), phase. It has the composition Al63Cu24Fe13 and is a mineral approved by the International Mineralogical Association in 2010. Its discovery followed a 10-year-long sy ...

, an aluminium-iron-copper alloy, as a mineral; named for its unique natural icosahedral symmetry

In mathematics, and especially in geometry, an object has icosahedral symmetry if it has the same symmetries as a regular icosahedron. Examples of other polyhedra with icosahedral symmetry include the regular dodecahedron (the dual polyhedr ...

, it is a quasicrystal

A quasiperiodicity, quasiperiodic crystal, or quasicrystal, is a structure that is Order and disorder (physics), ordered but not Bravais lattice, periodic. A quasicrystalline pattern can continuously fill all available space, but it lacks trans ...

. Unlike a true crystal, quasicrystals are ordered but not periodic.

Rocks, ores, and gems

A rock is an aggregate of one or more minerals, pp. 15–16 or mineraloids. Some rocks, such as

A rock is an aggregate of one or more minerals, pp. 15–16 or mineraloids. Some rocks, such as limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

or quartzite, are composed primarily of one mineral – calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

or aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral and one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate (), the others being calcite and vaterite. It is formed by biological and physical processes, including precipitation fr ...

in the case of limestone, and quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

in the latter case. Other rocks can be defined by relative abundances of key (essential) minerals; a granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

is defined by proportions of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase feldspar. The other minerals in the rock are termed ''accessory minerals'', and do not greatly affect the bulk composition of the rock. Rocks can also be composed entirely of non-mineral material; coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

is a sedimentary rock composed primarily of organically derived carbon.

In rocks, some mineral species and groups are much more abundant than others; these are termed the ''rock-forming minerals''. The major examples of these are quartz, the feldspar

Feldspar ( ; sometimes spelled felspar) is a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagiocl ...

s, the micas, the amphiboles, the pyroxenes, the olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron Silicate minerals, silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of Nesosilicates, nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle, it is a com ...

s, and calcite; except for the last one, all of these minerals are silicates. Overall, around 150 minerals are considered particularly important, whether in terms of their abundance or aesthetic value in terms of collecting., p. 14

Commercially valuable minerals and rocks, other than gemstones, metal ores, or mineral fuels, are referred to as ''industrial minerals

Industrial resources (minerals) are geological materials that are mined for their commercial value, which are not fuel (Fuel, fuel minerals or mineral fuels) and are not sources of metals (metallic minerals) but are used in the industries based ...

''. For example, muscovite, a white mica, can be used for windows (sometimes referred to as isinglass), as a filler, or as an insulator.

Ores are minerals that have a high concentration of a certain element, typically a metal. Examples are cinnabar

Cinnabar (; ), or cinnabarite (), also known as ''mercurblende'' is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of Mercury sulfide, mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining mercury (element), elemental mercury and is t ...

(HgS), an ore of mercury; sphalerite

Sphalerite is a sulfide mineral with the chemical formula . It is the most important ore of zinc. Sphalerite is found in a variety of deposit types, but it is primarily in Sedimentary exhalative deposits, sedimentary exhalative, Carbonate-hoste ...

(ZnS), an ore of zinc; cassiterite (SnO2), an ore of tin; and colemanite, an ore of boron.

''Gems'' are minerals with an ornamental value, and are distinguished from non-gems by their beauty, durability, and usually, rarity. There are about 20 mineral species that qualify as gem minerals, which constitute about 35 of the most common gemstones. Gem minerals are often present in several varieties, and so one mineral can account for several different gemstones; for example, ruby

Ruby is a pinkish-red-to-blood-red-colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum ( aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapph ...

and sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide () with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, cobalt, lead, chromium, vanadium, magnesium, boron, and silicon. The name ''sapphire ...

are both corundum, Al2O3., pp. 14–15

Etymology

The first known use of the word "mineral" in theEnglish language

English is a West Germanic language that developed in early medieval England and has since become a English as a lingua franca, global lingua franca. The namesake of the language is the Angles (tribe), Angles, one of the Germanic peoples th ...

(Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

) was the 15th century. The word came from , from , mine, ore.mineral" entry in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Accessed on 2020-08-28. The word "species" comes from the Latin ''species'', "a particular sort, kind, or type with distinct look, or appearance".

Chemistry

The abundance and diversity of minerals is controlled directly by their chemistry, in turn dependent on elemental abundances in the Earth. The majority of minerals observed are derived from the

The abundance and diversity of minerals is controlled directly by their chemistry, in turn dependent on elemental abundances in the Earth. The majority of minerals observed are derived from the Earth's crust

Earth's crust is its thick outer shell of rock, referring to less than one percent of the planet's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a solidified division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper ...

. Eight elements account for most of the key components of minerals, due to their abundance in the crust. These eight elements, summing to over 98% of the crust by weight, are, in order of decreasing abundance: oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

, aluminium

Aluminium (or aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Al and atomic number 13. It has a density lower than that of other common metals, about one-third that of steel. Aluminium has ...

, iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

, sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

and potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

. Oxygen and silicon are by far the two most important – oxygen composes 47% of the crust by weight, and silicon accounts for 28%., pp. 4–7

The minerals that form are those that are most stable at the temperature and pressure of formation, within the limits imposed by the bulk chemistry of the parent body. For example, in most igneous rocks, the aluminium and alkali metals (sodium and potassium) that are present are primarily found in combination with oxygen, silicon, and calcium as feldspar minerals. However, if the rock is unusually rich in alkali metals, there will not be enough aluminium to combine with all the sodium as feldspar, and the excess sodium will form sodic amphiboles such as riebeckite. If the aluminium abundance is unusually high, the excess aluminium will form muscovite or other aluminium-rich minerals. If silicon is deficient, part of the feldspar will be replaced by feldspathoid minerals. Precise predictions of which minerals will be present in a rock of a particular composition formed at a particular temperature and pressure requires complex thermodynamic calculations. However, approximate estimates may be made using relatively simple rules of thumb, such as the CIPW norm, which gives reasonable estimates for volcanic rock formed from dry magma.

The chemical composition may vary between end member species of a solid solution

A solid solution, a term popularly used for metals, is a homogeneous mixture of two compounds in solid state and having a single crystal structure. Many examples can be found in metallurgy, geology, and solid-state chemistry. The word "solutio ...

series. For example, the plagioclase

Plagioclase ( ) is a series of Silicate minerals#Tectosilicates, tectosilicate (framework silicate) minerals within the feldspar group. Rather than referring to a particular mineral with a specific chemical composition, plagioclase is a continu ...

feldspar

Feldspar ( ; sometimes spelled felspar) is a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagiocl ...

s comprise a continuous series from sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

-rich end member albite

Albite is a plagioclase feldspar mineral. It is the sodium endmember of the plagioclase solid solution series. It represents a plagioclase with less than 10% anorthite content. The pure albite endmember has the formula . It is a tectosilicat ...

(NaAlSi3O8) to calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

-rich anorthite

Anorthite (< ''an'' 'not' + ''ortho'' 'straight') is the

oligoclase, andesine, labradorite, and bytownite. Other examples of series include the olivine series of magnesium-rich forsterite and iron-rich fayalite, and the wolframite series of  Changes in temperature and pressure and composition alter the mineralogy of a rock sample. Changes in composition can be caused by processes such as weathering or metasomatism (

Changes in temperature and pressure and composition alter the mineralogy of a rock sample. Changes in composition can be caused by processes such as weathering or metasomatism (

Twinning is the intergrowth of two or more crystals of a single mineral species. The geometry of the twinning is controlled by the mineral's symmetry. As a result, there are several types of twins, including contact twins, reticulated twins, geniculated twins, penetration twins, cyclic twins, and polysynthetic twins. Contact, or simple twins, consist of two crystals joined at a plane; this type of twinning is common in spinel. Reticulated twins, common in rutile, are interlocking crystals resembling netting. Geniculated twins have a bend in the middle that is caused by start of the twin. Penetration twins consist of two single crystals that have grown into each other; examples of this twinning include cross-shaped staurolite twins and Carlsbad twinning in orthoclase. Cyclic twins are caused by repeated twinning around a rotation axis. This type of twinning occurs around three, four, five, six, or eight-fold axes, and the corresponding patterns are called threelings, fourlings, fivelings, sixlings, and eightlings. Sixlings are common in aragonite. Polysynthetic twins are similar to cyclic twins through the presence of repetitive twinning; however, instead of occurring around a rotational axis, polysynthetic twinning occurs along parallel planes, usually on a microscopic scale., pp. 41–43

Crystal habit refers to the overall shape of the aggregate crystal of any mineral. Several terms are used to describe this property. Common habits include acicular, which describes needle-like crystals as in natrolite; dendritic (tree-pattern) is common in native copper or native gold with a groundmass (matrix); equant, which is typical of

Twinning is the intergrowth of two or more crystals of a single mineral species. The geometry of the twinning is controlled by the mineral's symmetry. As a result, there are several types of twins, including contact twins, reticulated twins, geniculated twins, penetration twins, cyclic twins, and polysynthetic twins. Contact, or simple twins, consist of two crystals joined at a plane; this type of twinning is common in spinel. Reticulated twins, common in rutile, are interlocking crystals resembling netting. Geniculated twins have a bend in the middle that is caused by start of the twin. Penetration twins consist of two single crystals that have grown into each other; examples of this twinning include cross-shaped staurolite twins and Carlsbad twinning in orthoclase. Cyclic twins are caused by repeated twinning around a rotation axis. This type of twinning occurs around three, four, five, six, or eight-fold axes, and the corresponding patterns are called threelings, fourlings, fivelings, sixlings, and eightlings. Sixlings are common in aragonite. Polysynthetic twins are similar to cyclic twins through the presence of repetitive twinning; however, instead of occurring around a rotational axis, polysynthetic twinning occurs along parallel planes, usually on a microscopic scale., pp. 41–43

Crystal habit refers to the overall shape of the aggregate crystal of any mineral. Several terms are used to describe this property. Common habits include acicular, which describes needle-like crystals as in natrolite; dendritic (tree-pattern) is common in native copper or native gold with a groundmass (matrix); equant, which is typical of

The hardness of a mineral defines how much it can resist scratching or indentation. This physical property is controlled by the chemical composition and crystalline structure of a mineral.

The most commonly used scale of measurement is the ordinal Mohs hardness scale, which measures resistance to scratching. Defined by ten indicators, a mineral with a higher index scratches those below it. The scale ranges from talc, a phyllosilicate, to diamond, a carbon polymorph that is the hardest natural material. The scale is provided below:

The hardness of a mineral defines how much it can resist scratching or indentation. This physical property is controlled by the chemical composition and crystalline structure of a mineral.

The most commonly used scale of measurement is the ordinal Mohs hardness scale, which measures resistance to scratching. Defined by ten indicators, a mineral with a higher index scratches those below it. The scale ranges from talc, a phyllosilicate, to diamond, a carbon polymorph that is the hardest natural material. The scale is provided below:

A mineral's hardness is a function of its structure. Hardness is not necessarily constant for all crystallographic directions; crystallographic weakness renders some directions softer than others., pp. 28–29 An example of this hardness variability exists in kyanite, which has a Mohs hardness of 5 parallel to 01but 7 parallel to 00

Other scales include these;

* Shore's hardness test, which measures the endurance of a mineral based on the indentation of a spring-loaded contraption.

*The

A mineral's hardness is a function of its structure. Hardness is not necessarily constant for all crystallographic directions; crystallographic weakness renders some directions softer than others., pp. 28–29 An example of this hardness variability exists in kyanite, which has a Mohs hardness of 5 parallel to 01but 7 parallel to 00

Other scales include these;

* Shore's hardness test, which measures the endurance of a mineral based on the indentation of a spring-loaded contraption.

*The

Lustre indicates how light reflects from the mineral's surface, with regards to its quality and intensity. There are numerous qualitative terms used to describe this property, which are split into metallic and non-metallic categories. Metallic and sub-metallic minerals have high reflectivity like metal; examples of minerals with this lustre are

Lustre indicates how light reflects from the mineral's surface, with regards to its quality and intensity. There are numerous qualitative terms used to describe this property, which are split into metallic and non-metallic categories. Metallic and sub-metallic minerals have high reflectivity like metal; examples of minerals with this lustre are

By definition, minerals have a characteristic atomic arrangement. Weakness in this crystalline structure causes planes of weakness, and the breakage of a mineral along such planes is termed cleavage. The quality of cleavage can be described based on how cleanly and easily the mineral breaks; common descriptors, in order of decreasing quality, are "perfect", "good", "distinct", and "poor". In particularly transparent minerals, or in thin-section, cleavage can be seen as a series of parallel lines marking the planar surfaces when viewed from the side. Cleavage is not a universal property among minerals; for example, quartz, consisting of extensively interconnected silica tetrahedra, does not have a crystallographic weakness which would allow it to cleave. In contrast, micas, which have perfect basal cleavage, consist of sheets of silica tetrahedra which are very weakly held together., pp. 29–30

As cleavage is a function of crystallography, there are a variety of cleavage types. Cleavage occurs typically in either one, two, three, four, or six directions. Basal cleavage in one direction is a distinctive property of the micas. Two-directional cleavage is described as prismatic, and occurs in minerals such as the amphiboles and pyroxenes. Minerals such as galena or halite have cubic (or isometric) cleavage in three directions, at 90°; when three directions of cleavage are present, but not at 90°, such as in calcite or

By definition, minerals have a characteristic atomic arrangement. Weakness in this crystalline structure causes planes of weakness, and the breakage of a mineral along such planes is termed cleavage. The quality of cleavage can be described based on how cleanly and easily the mineral breaks; common descriptors, in order of decreasing quality, are "perfect", "good", "distinct", and "poor". In particularly transparent minerals, or in thin-section, cleavage can be seen as a series of parallel lines marking the planar surfaces when viewed from the side. Cleavage is not a universal property among minerals; for example, quartz, consisting of extensively interconnected silica tetrahedra, does not have a crystallographic weakness which would allow it to cleave. In contrast, micas, which have perfect basal cleavage, consist of sheets of silica tetrahedra which are very weakly held together., pp. 29–30

As cleavage is a function of crystallography, there are a variety of cleavage types. Cleavage occurs typically in either one, two, three, four, or six directions. Basal cleavage in one direction is a distinctive property of the micas. Two-directional cleavage is described as prismatic, and occurs in minerals such as the amphiboles and pyroxenes. Minerals such as galena or halite have cubic (or isometric) cleavage in three directions, at 90°; when three directions of cleavage are present, but not at 90°, such as in calcite or

Specific gravity numerically describes the

Specific gravity numerically describes the

Other properties can be used to diagnose minerals. These are less general, and apply to specific minerals.

Dropping dilute

Other properties can be used to diagnose minerals. These are less general, and apply to specific minerals.

Dropping dilute

The base unit of a silicate mineral is the iO4sup>4− tetrahedron. In the vast majority of cases, silicon is in four-fold or tetrahedral coordination with oxygen. In very high-pressure situations, silicon will be in six-fold or octahedral coordination, such as in the perovskite structure or the quartz polymorph stishovite (SiO2). In the latter case, the mineral no longer has a silicate structure, but that of

The base unit of a silicate mineral is the iO4sup>4− tetrahedron. In the vast majority of cases, silicon is in four-fold or tetrahedral coordination with oxygen. In very high-pressure situations, silicon will be in six-fold or octahedral coordination, such as in the perovskite structure or the quartz polymorph stishovite (SiO2). In the latter case, the mineral no longer has a silicate structure, but that of

Tectosilicates, also known as framework silicates, have the highest degree of polymerization. With all corners of a tetrahedra shared, the silicon:oxygen ratio becomes 1:2. Examples are quartz, the

Tectosilicates, also known as framework silicates, have the highest degree of polymerization. With all corners of a tetrahedra shared, the silicon:oxygen ratio becomes 1:2. Examples are quartz, the

manganese

Manganese is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese was first isolated in the 1770s. It is a transition m ...

-rich hübnerite and iron-rich ferberite.

Chemical substitution and coordination polyhedra explain this common feature of minerals. In nature, minerals are not pure substances, and are contaminated by whatever other elements are present in the given chemical system. As a result, it is possible for one element to be substituted for another. Chemical substitution will occur between ions of a similar size and charge; for example, K+ will not substitute for Si4+ because of chemical and structural incompatibilities caused by a big difference in size and charge. A common example of chemical substitution is that of Si4+ by Al3+, which are close in charge, size, and abundance in the crust. In the example of plagioclase, there are three cases of substitution. Feldspars are all framework silicates, which have a silicon-oxygen ratio of 2:1, and the space for other elements is given by the substitution of Si4+ by Al3+ to give a base unit of lSi3O8sup>−; without the substitution, the formula would be charge-balanced as SiO2, giving quartz. The significance of this structural property will be explained further by coordination polyhedra. The second substitution occurs between Na+ and Ca2+; however, the difference in charge has to accounted for by making a second substitution of Si4+ by Al3+.

Coordination polyhedra are geometric representations of how a cation is surrounded by an anion. In mineralogy, coordination polyhedra are usually considered in terms of oxygen, due its abundance in the crust. The base unit of silicate minerals is the silica tetrahedron – one Si4+ surrounded by four O2−. An alternate way of describing the coordination of the silicate is by a number: in the case of the silica tetrahedron, the silicon is said to have a coordination number of 4. Various cations have a specific range of possible coordination numbers; for silicon, it is almost always 4, except for very high-pressure minerals where the compound is compressed such that silicon is in six-fold (octahedral) coordination with oxygen. Bigger cations have a bigger coordination numbers because of the increase in relative size as compared to oxygen (the last orbital subshell of heavier atoms is different too). Changes in coordination numbers leads to physical and mineralogical differences; for example, at high pressure, such as in the mantle, many minerals, especially silicates such as olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron Silicate minerals, silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of Nesosilicates, nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle, it is a com ...

and garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

Garnet minerals, while sharing similar physical and crystallographic properties, exhibit a wide range of chemical compositions, de ...

, will change to a perovskite structure, where silicon is in octahedral coordination. Other examples are the aluminosilicates kyanite, andalusite, and sillimanite (polymorphs, since they share the formula Al2SiO5), which differ by the coordination number of the Al3+; these minerals transition from one another as a response to changes in pressure and temperature. In the case of silicate materials, the substitution of Si4+ by Al3+ allows for a variety of minerals because of the need to balance charges.

Because the eight most common elements make up over 98% of the Earth's crust, the small quantities of the other elements that are typically present are substituted into the common rock-forming minerals. The distinctive minerals of most elements are quite rare, being found only where these elements have been concentrated by geological processes, such as hydrothermal circulation

Hydrothermal circulation in its most general sense is the circulation of hot water (Ancient Greek ὕδωρ, ''water'',Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with th ...

, to the point where they can no longer be accommodated in common minerals.

Changes in temperature and pressure and composition alter the mineralogy of a rock sample. Changes in composition can be caused by processes such as weathering or metasomatism (

Changes in temperature and pressure and composition alter the mineralogy of a rock sample. Changes in composition can be caused by processes such as weathering or metasomatism (hydrothermal alteration

Metasomatism (from the Greek μετά ''metá'' "change" and σῶμα ''sôma'' "body") is the chemical alteration of a Rock (geology), rock by hydrothermal and other fluids. It is traditionally defined as metamorphism which involves a change in t ...

). Changes in temperature and pressure occur when the host rock undergoes tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

or magmatic movement into differing physical regimes. Changes in thermodynamic conditions make it favourable for mineral assemblages to react with each other to produce new minerals; as such, it is possible for two rocks to have an identical or a very similar bulk rock chemistry without having a similar mineralogy. This process of mineralogical alteration is related to the rock cycle. An example of a series of mineral reactions is illustrated as follows., p. 549

Orthoclase

Orthoclase, or orthoclase feldspar ( endmember formula K Al Si3 O8), is an important tectosilicate mineral which forms igneous rock. The name is from the Ancient Greek for "straight fracture", because its two cleavage planes are at right angles ...

feldspar (KAlSi3O8) is a mineral commonly found in granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

, a plutonic igneous rock

Igneous rock ( ), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

The magma can be derived from partial ...

. When exposed to weathering, it reacts to form kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4, a sedimentary mineral, and silicic acid):

:2 KAlSi3O8 + 5 H2O + 2 H+ → Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 4 H2SiO3 + 2 K+

Under low-grade metamorphic conditions, kaolinite reacts with quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

to form pyrophyllite (Al2Si4O10(OH)2):

:Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + SiO2 → Al2Si4O10(OH)2 + H2O

As metamorphic grade increases, the pyrophyllite reacts to form kyanite and quartz:

:Al2Si4O10(OH)2 → Al2SiO5 + 3 SiO2 + H2O

Alternatively, a mineral may change its crystal structure as a consequence of changes in temperature and pressure without reacting. For example, quartz will change into a variety of its SiO2 polymorphs, such as tridymite

Tridymite is a high-temperature polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of silica and usually occurs as minute tabular white or colorless pseudo-hexagonal crystals, or scales, in cavities in felsic volcanic rocks. Its chemical formula is sili ...

and cristobalite

Cristobalite ( ) is a mineral polymorph of silica that is formed at very high temperatures. It has the same chemical formula as quartz, Si O2, but a distinct crystal structure. Both quartz and cristobalite are polymorphs with all the members o ...

at high temperatures, and coesite

Coesite () is a form (polymorphism (materials science), polymorph) of silicon dioxide (silicon, Sioxide, O2) that is formed when very high pressure (2–3 gigapascals), and moderately high temperature (), are applied to quartz. Coesite was first ...

at high pressures.

Physical properties

Classifying minerals ranges from simple to difficult. A mineral can be identified by several physical properties, some of them being sufficient for full identification without equivocation. In other cases, minerals can only be classified by more complex optical,chemical

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combin ...

or X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the waves. ...

analysis; these methods, however, can be costly and time-consuming. Physical properties applied for classification include crystal structure and habit, hardness, lustre, diaphaneity, colour, streak, cleavage and fracture, and specific gravity. Other less general tests include fluorescence

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with colore ...

, phosphorescence

Phosphorescence is a type of photoluminescence related to fluorescence. When exposed to light (radiation) of a shorter wavelength, a phosphorescent substance will glow, absorbing the light and reemitting it at a longer wavelength. Unlike fluor ...

, magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

, radioactivity

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

, tenacity (response to mechanical induced changes of shape or form), piezoelectricity and reactivity to dilute acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

s.

Crystal structure and habit

Crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat ...

results from the orderly geometric spatial arrangement of atoms in the internal structure of a mineral. This crystal structure is based on regular internal atomic or ionic arrangement that is often expressed in the geometric form that the crystal takes. Even when the mineral grains are too small to see or are irregularly shaped, the underlying crystal structure is always periodic and can be determined by X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

diffraction. Minerals are typically described by their symmetry content. Crystals are restricted to 32 point groups, which differ by their symmetry. These groups are classified in turn into more broad categories, the most encompassing of these being the six crystal families., pp. 69–80

These families can be described by the relative lengths of the three crystallographic axes, and the angles between them; these relationships correspond to the symmetry operations that define the narrower point groups. They are summarized below; a, b, and c represent the axes, and α, β, γ represent the angle opposite the respective crystallographic axis (e.g. α is the angle opposite the a-axis, viz. the angle between the b and c axes):

The hexagonal crystal family is also split into two crystal ''systems'' – the trigonal

In crystallography, the hexagonal crystal family is one of the six crystal family, crystal families, which includes two crystal systems (hexagonal and trigonal) and two lattice systems (hexagonal and rhombohedral). While commonly confused, the tr ...

, which has a three-fold axis of symmetry, and the hexagonal, which has a six-fold axis of symmetry.

Chemistry and crystal structure together define a mineral. With a restriction to 32 point groups, minerals of different chemistry may have identical crystal structure. For example, halite (NaCl), galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

(PbS), and periclase (MgO) all belong to the hexaoctahedral point group (isometric family), as they have a similar stoichiometry

Stoichiometry () is the relationships between the masses of reactants and Product (chemistry), products before, during, and following chemical reactions.

Stoichiometry is based on the law of conservation of mass; the total mass of reactants must ...

between their different constituent elements. In contrast, polymorphs are groupings of minerals that share a chemical formula but have a different structure. For example, pyrite and marcasite, both iron sulfides, have the formula FeS2; however, the former is isometric while the latter is orthorhombic. This polymorphism extends to other sulfides with the generic AX2 formula; these two groups are collectively known as the pyrite and marcasite groups.

Polymorphism can extend beyond pure symmetry content. The aluminosilicates are a group of three minerals – kyanite, andalusite, and sillimanite – which share the chemical formula Al2SiO5. Kyanite is triclinic, while andalusite and sillimanite are both orthorhombic and belong to the dipyramidal point group. These differences arise corresponding to how aluminium is coordinated within the crystal structure. In all minerals, one aluminium ion is always in six-fold coordination with oxygen. Silicon, as a general rule, is in four-fold coordination in all minerals; an exception is a case like stishovite (SiO2, an ultra-high pressure quartz polymorph with rutile structure). In kyanite, the second aluminium is in six-fold coordination; its chemical formula can be expressed as Al /sup>Al /sup>SiO5, to reflect its crystal structure. Andalusite has the second aluminium in five-fold coordination (Al /sup>Al /sup>SiO5) and sillimanite has it in four-fold coordination (Al /sup>Al /sup>SiO5).

Differences in crystal structure and chemistry greatly influence other physical properties of the mineral. The carbon allotropes diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

and graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

have vastly different properties; diamond is the hardest natural substance, has an adamantine lustre, and belongs to the isometric crystal family, whereas graphite is very soft, has a greasy lustre, and crystallises in the hexagonal family. This difference is accounted for by differences in bonding. In diamond, the carbons are in sp3 hybrid orbitals, which means they form a framework where each carbon is covalently bonded to four neighbours in a tetrahedral fashion; on the other hand, graphite is composed of sheets of carbons in sp2 hybrid orbitals, where each carbon is bonded covalently to only three others. These sheets are held together by much weaker van der Waals forces, and this discrepancy translates to large macroscopic differences.

Twinning is the intergrowth of two or more crystals of a single mineral species. The geometry of the twinning is controlled by the mineral's symmetry. As a result, there are several types of twins, including contact twins, reticulated twins, geniculated twins, penetration twins, cyclic twins, and polysynthetic twins. Contact, or simple twins, consist of two crystals joined at a plane; this type of twinning is common in spinel. Reticulated twins, common in rutile, are interlocking crystals resembling netting. Geniculated twins have a bend in the middle that is caused by start of the twin. Penetration twins consist of two single crystals that have grown into each other; examples of this twinning include cross-shaped staurolite twins and Carlsbad twinning in orthoclase. Cyclic twins are caused by repeated twinning around a rotation axis. This type of twinning occurs around three, four, five, six, or eight-fold axes, and the corresponding patterns are called threelings, fourlings, fivelings, sixlings, and eightlings. Sixlings are common in aragonite. Polysynthetic twins are similar to cyclic twins through the presence of repetitive twinning; however, instead of occurring around a rotational axis, polysynthetic twinning occurs along parallel planes, usually on a microscopic scale., pp. 41–43

Crystal habit refers to the overall shape of the aggregate crystal of any mineral. Several terms are used to describe this property. Common habits include acicular, which describes needle-like crystals as in natrolite; dendritic (tree-pattern) is common in native copper or native gold with a groundmass (matrix); equant, which is typical of

Twinning is the intergrowth of two or more crystals of a single mineral species. The geometry of the twinning is controlled by the mineral's symmetry. As a result, there are several types of twins, including contact twins, reticulated twins, geniculated twins, penetration twins, cyclic twins, and polysynthetic twins. Contact, or simple twins, consist of two crystals joined at a plane; this type of twinning is common in spinel. Reticulated twins, common in rutile, are interlocking crystals resembling netting. Geniculated twins have a bend in the middle that is caused by start of the twin. Penetration twins consist of two single crystals that have grown into each other; examples of this twinning include cross-shaped staurolite twins and Carlsbad twinning in orthoclase. Cyclic twins are caused by repeated twinning around a rotation axis. This type of twinning occurs around three, four, five, six, or eight-fold axes, and the corresponding patterns are called threelings, fourlings, fivelings, sixlings, and eightlings. Sixlings are common in aragonite. Polysynthetic twins are similar to cyclic twins through the presence of repetitive twinning; however, instead of occurring around a rotational axis, polysynthetic twinning occurs along parallel planes, usually on a microscopic scale., pp. 41–43

Crystal habit refers to the overall shape of the aggregate crystal of any mineral. Several terms are used to describe this property. Common habits include acicular, which describes needle-like crystals as in natrolite; dendritic (tree-pattern) is common in native copper or native gold with a groundmass (matrix); equant, which is typical of garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

Garnet minerals, while sharing similar physical and crystallographic properties, exhibit a wide range of chemical compositions, de ...

; prismatic (elongated in one direction) as seen in kunzite

Spodumene is a pyroxene mineral consisting of lithium aluminium Silicate minerals#Inosilicates, inosilicate, lithium, Lialuminum, Al(silicon, Sioxygen, O3)2, and is a commercially important source of lithium. It occurs as colorless to yellowish, ...

or stibnite; botryoidal (like a bunch of grapes) seen in chalcedony; fibrous, which has fibre-like crystals as seen in wollastonite

Wollastonite is a calcium Silicate minerals, inosilicate mineral (calcium, Casilicon, Sioxygen, O3) that may contain small amounts of iron, magnesium, and manganese substituting for calcium. It is usually white. It forms when impure limestone or D ...

; tabular, which differs from bladed habit in that the former is platy whereas the latter has a defined elongation as seen in muscovite; and massive, which has no definite shape as seen in carnallite. Related to crystal form, the quality of crystal faces is diagnostic of some minerals, especially with a petrographic microscope. Euhedral crystals have a defined external shape, while anhedral crystals do not; those intermediate forms are termed subhedral.

Hardness

The hardness of a mineral defines how much it can resist scratching or indentation. This physical property is controlled by the chemical composition and crystalline structure of a mineral.

The most commonly used scale of measurement is the ordinal Mohs hardness scale, which measures resistance to scratching. Defined by ten indicators, a mineral with a higher index scratches those below it. The scale ranges from talc, a phyllosilicate, to diamond, a carbon polymorph that is the hardest natural material. The scale is provided below:

The hardness of a mineral defines how much it can resist scratching or indentation. This physical property is controlled by the chemical composition and crystalline structure of a mineral.

The most commonly used scale of measurement is the ordinal Mohs hardness scale, which measures resistance to scratching. Defined by ten indicators, a mineral with a higher index scratches those below it. The scale ranges from talc, a phyllosilicate, to diamond, a carbon polymorph that is the hardest natural material. The scale is provided below:

Rockwell scale

The Rockwell hardness test is a hardness test based on indentation hardness of a material. The Rockwell test measures the depth of penetration of an indenter under a large load (major load) compared to the penetration made by a preload (minor loa ...

*The Vickers hardness test

The Vickers hardness test was developed in 1921 by Robert L. Smith and George E. Sandland at Vickers Ltd as an alternative to the Brinell scale, Brinell method to measure the hardness of materials. The Vickers test is often easier to use than ot ...

*The Brinell scale

The Brinell hardness test (pronounced /brəˈnɛl/) measures the indentation hardness of materials. It determines hardness through the scale of penetration of an indenter, loaded on a material test-piece. It is one of several definitions of hard ...

Lustre and diaphaneity

Lustre indicates how light reflects from the mineral's surface, with regards to its quality and intensity. There are numerous qualitative terms used to describe this property, which are split into metallic and non-metallic categories. Metallic and sub-metallic minerals have high reflectivity like metal; examples of minerals with this lustre are

Lustre indicates how light reflects from the mineral's surface, with regards to its quality and intensity. There are numerous qualitative terms used to describe this property, which are split into metallic and non-metallic categories. Metallic and sub-metallic minerals have high reflectivity like metal; examples of minerals with this lustre are galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

and pyrite. Non-metallic lustres include: adamantine, such as in diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

; vitreous, which is a glassy lustre very common in silicate minerals; pearly, such as in talc and apophyllite; resinous, such as members of the garnet group; silky which is common in fibrous minerals such as asbestiform chrysotile.Dyar and Darby, pp. 26–28

The diaphaneity of a mineral describes the ability of light to pass through it. Transparent minerals do not diminish the intensity of light passing through them. An example of a transparent mineral is muscovite (potassium mica); some varieties are sufficiently clear to have been used for windows. Translucent minerals allow some light to pass, but less than those that are transparent. Jadeite and nephrite (mineral forms of jade

Jade is an umbrella term for two different types of decorative rocks used for jewelry or Ornament (art), ornaments. Jade is often referred to by either of two different silicate mineral names: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in t ...

are examples of minerals with this property). Minerals that do not allow light to pass are called opaque., p. 25

The diaphaneity of a mineral depends on the thickness of the sample. When a mineral is sufficiently thin (e.g., in a thin section for petrography

Petrography is a branch of petrology that focuses on detailed descriptions of rocks. Someone who studies petrography is called a petrographer. The mineral content and the textural relationships within the rock are described in detail. The clas ...

), it may become transparent even if that property is not seen in a hand sample. In contrast, some minerals, such as hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

or pyrite, are opaque even in thin-section.

Colour and streak

Colour is the most obvious property of a mineral, but it is often non-diagnostic. It is caused byelectromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

interacting with electrons (except in the case of incandescence

Thermal radiation is electromagnetic radiation emitted by the thermal motion of particles in matter. All matter with a temperature greater than absolute zero emits thermal radiation. The emission of energy arises from a combination of electron ...

, which does not apply to minerals)., pp. 131–44 Two broad classes of elements (idiochromatic and allochromatic) are defined with regards to their contribution to a mineral's colour: Idiochromatic elements are essential to a mineral's composition; their contribution to a mineral's colour is diagnostic., p. 72, p. 24 Examples of such minerals are malachite (green) and azurite (blue). In contrast, allochromatic elements in minerals are present in trace amounts as impurities. An example of such a mineral would be the ruby

Ruby is a pinkish-red-to-blood-red-colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum ( aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapph ...

and sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide () with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, cobalt, lead, chromium, vanadium, magnesium, boron, and silicon. The name ''sapphire ...

varieties of the mineral corundum.

The colours of pseudochromatic minerals are the result of interference of light waves. Examples include labradorite and bornite.

In addition to simple body colour, minerals can have various other distinctive optical properties, such as play of colours, asterism, chatoyancy, iridescence, tarnish, and pleochroism. Several of these properties involve variability in colour. Play of colour, such as in opal

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silicon dioxide, silica (SiO2·''n''H2O); its water content may range from 3% to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6% and 10%. Due to the amorphous (chemical) physical structure, it is classified as a ...