Mills Commission on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Abraham Gilbert Mills (March 12, 1844 – August 26, 1929) was an American baseball executive. He was the fourth president of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (1883–1884), and is best known for heading the "Mills Commission" which controversially credited

Abraham Gilbert Mills (March 12, 1844 – August 26, 1929) was an American baseball executive. He was the fourth president of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (1883–1884), and is best known for heading the "Mills Commission" which controversially credited

A. G. Mills

Retrieved Oct. 10, 2006.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mills, Abraham 1844 births 1929 deaths Otis Worldwide Baseball executives National League presidents

Abraham Gilbert Mills (March 12, 1844 – August 26, 1929) was an American baseball executive. He was the fourth president of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (1883–1884), and is best known for heading the "Mills Commission" which controversially credited

Abraham Gilbert Mills (March 12, 1844 – August 26, 1929) was an American baseball executive. He was the fourth president of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (1883–1884), and is best known for heading the "Mills Commission" which controversially credited Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

general Abner Doubleday

Abner Doubleday (June 26, 1819 – January 26, 1893) was a career United States Army officer and Union major general in the American Civil War. He fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, the opening battle of the war, and had a ...

with the invention of baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball sport played between two team sport, teams of nine players each, taking turns batting (baseball), batting and Fielding (baseball), fielding. The game occurs over the course of several Pitch ...

.

Early life

Mills was born on March 12, 1844, inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, and lived there until September 1862, when he enlisted in the United States Army. He served briefly as a Private in the 5th New York Volunteer Infantry

The 5th New York Infantry Regiment, also known as Duryée's Zouaves, was a volunteer infantry regiment that served in the U.S. Army during the American Civil War. Modeled, like other Union and Confederate infantry regiments, on the French '' Zo ...

before mustering as a Sergeant in the 165th New York Infantry Regiment

The 165th New York Infantry Regiment (aka, "2nd Battalion Duryée's Zouaves" and "Smith's Zouaves") was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 165th New York Infantry was organized at New York City, New ...

, considered a sister-regiment to the 5th New York Infantry. While in the service, Mills continued to play baseball and later recalled that he would always pack his bat and ball along with his field equipment. He participated in a well-attended Christmas Day

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A liturgical feast central to Christianity, Chri ...

baseball game at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina

Hilton Head Island, often referred to as simply Hilton Head, is a South Carolina Lowcountry, Lowcountry resort town and barrier island in Beaufort County, South Carolina, United States. It is northeast of Savannah, Georgia (as the crow flies), a ...

in 1862 between the 165th New York Volunteer Infantry and nine other soldiers from other Union Army regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

s. A reported 40,000 soldiers were in attendance. In 1864, Mills was promoted 2nd Lieutenant, before being honorably discharged at Charleston, South Carolina on September 1 1865. After the Civil War, Mills became a veteran companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or, simply, the Loyal Legion, is a United States military order organized on April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Union Army. The original membership was consisted ...

as Companion No. 07469; and a member of the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (United States Navy, U.S. Navy), and the United States Marine Corps, Marines who served in the American Ci ...

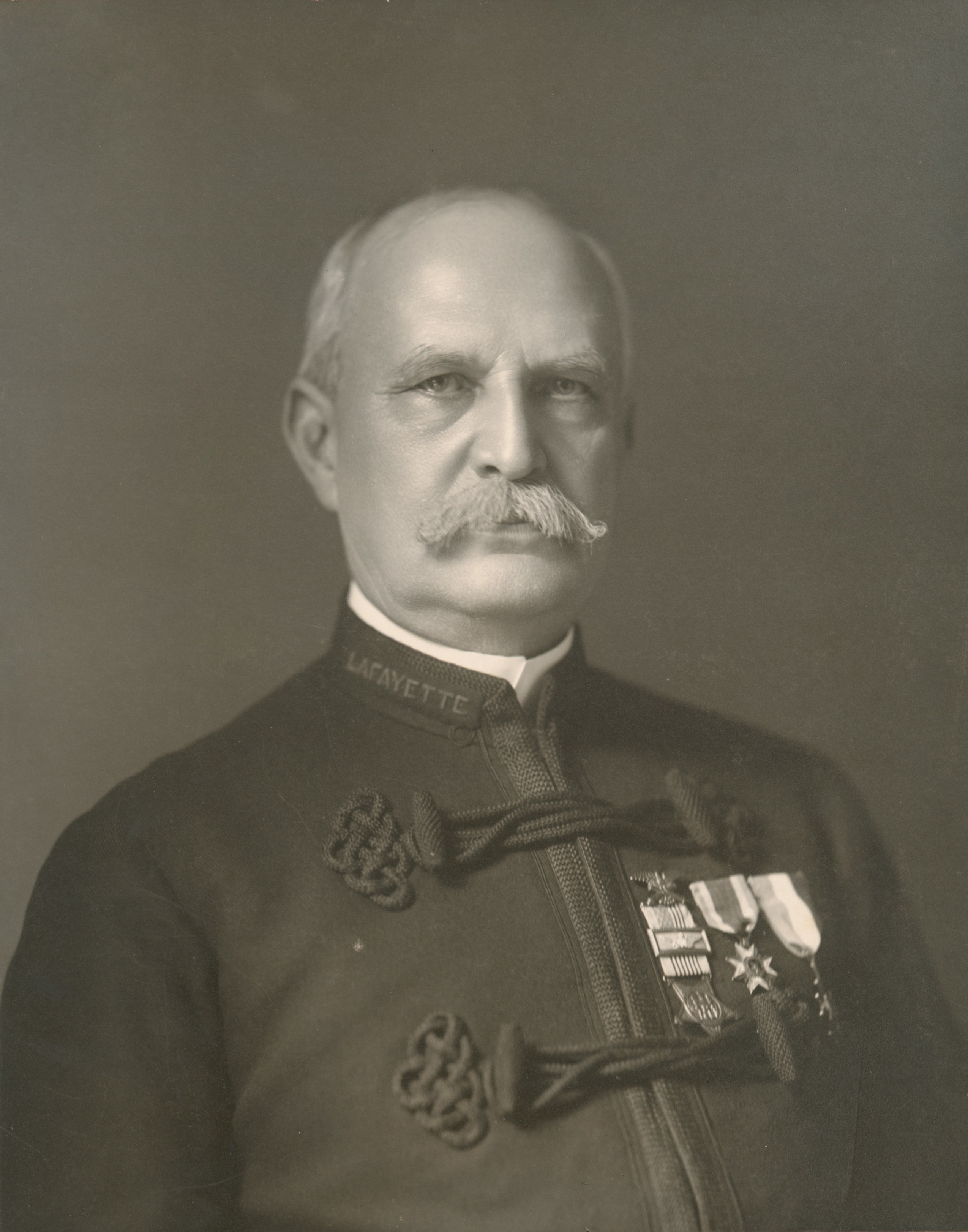

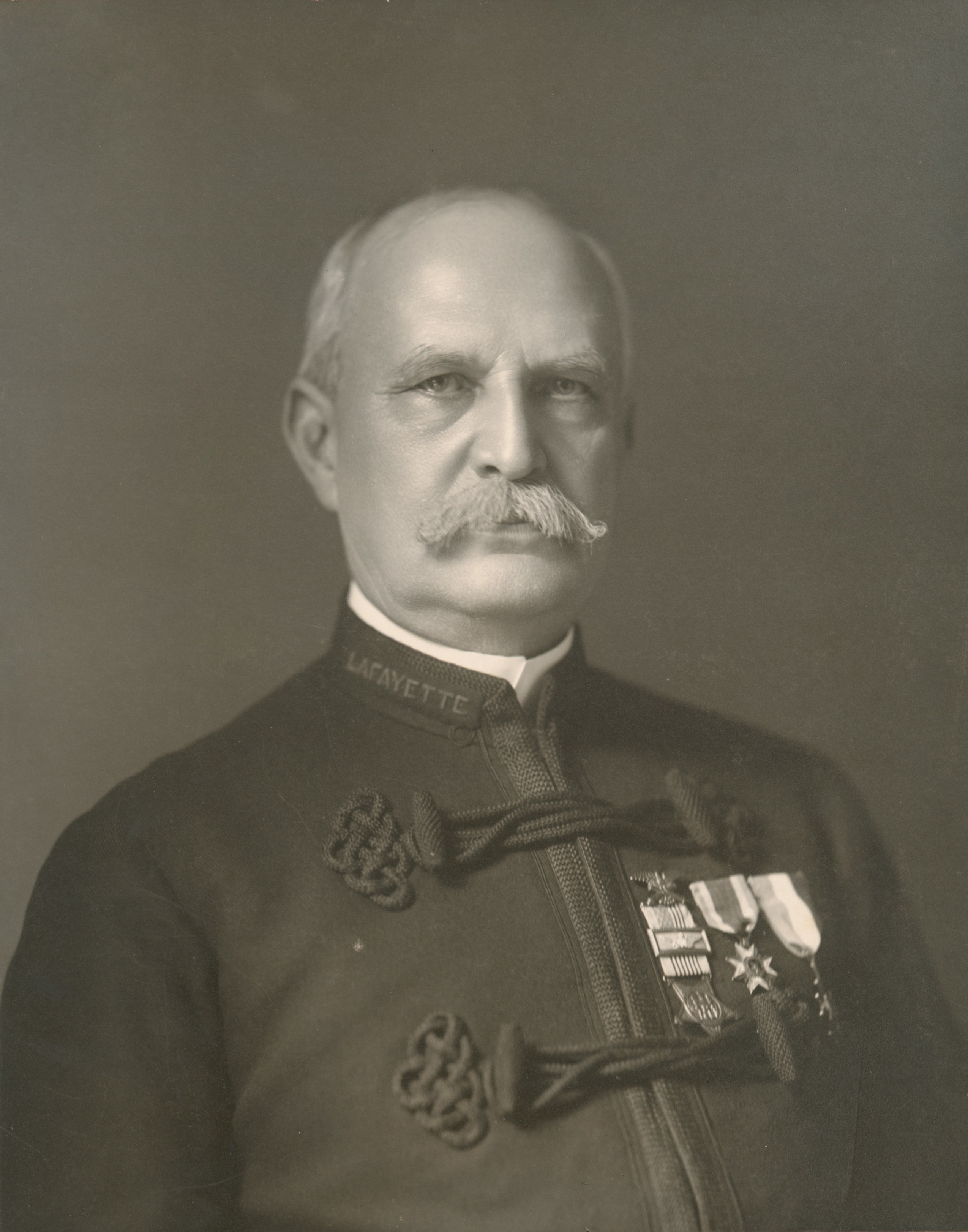

. He wears medals of both organizations in the photograph shown here.

After the war, Mills enrolled in Columbian Law School (now George Washington University) in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

to study law. While in Washington, Mills presided over the Olympic Base Ball Club for which he was also an occasional player. During his tenure, Mills tried unsuccessfully to recruit a young pitcher

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throws ("Pitch (baseball), pitches") the Baseball (ball), baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of out (baseball), retiring a batter (baseball), batter, ...

, Albert Spalding

Albert Goodwill Spalding (September 2, 1849 – September 9, 1915) was an American pitcher, manager, and executive in the early years of professional baseball, and the co-founder of the Spalding sporting goods company. He was born and raised i ...

, whose career he would later come to influence. In 1872 Mills married Mary Chester Steele, and the couple had three daughters. After being admitted to the bar in 1876, he relocated his family to Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

where his career took an unexpected turn.

National League presidency

During the late 19th century, it was common practice for professional leagues (such as theNational League

National League often refers to:

*National League (baseball), one of the two baseball leagues constituting Major League Baseball in the United States and Canada

*National League (division), the fifth division of the English football (soccer) system ...

) to sign players already under contract with non-league teams. Usually, several teammates were recruited together, forcing the depleted non-league team to disband. Mills attacked the questionable ethics of the practice in a newspaper article and outlined a plan to prevent the raiding of non-league teams. William Hulbert

William Ambrose Hulbert (October 23, 1832 – April 10, 1882) was an American professional baseball executive who was one of the founders of the National League, considered by many to be baseball's first major league, and was also the president ...

, then president of the NL, noticed the article and solicited Mills for his advice on drafting an official solution, which resulted in the "League Alliance

The League Alliance was the first semi-affiliated minor league baseball league. Proposed by Al Spalding

Albert Goodwill Spalding (September 2, 1849 – September 9, 1915) was an American pitcher, manager, and executive in the early years of p ...

" (1877). Mills' contribution impressed the league, and he was hired on as an advisor. Following Hulbert's death in 1882, the league unanimously elected him president.

Mills' primary objective as president sought to prevent players from switching from one professional league to the next, which they typically did during mid-season in search of higher salaries. In 1888, Mills called an assembly of representatives from the three professional leagues—the National League, American Association, and Northwestern League

The Northwestern League was a sports league that operated in the Central United States during the early years of professional baseball for six seasons: 1879, 1883–1884, 1886–1887, and 1891. After the 1887 season, the league was replaced by t ...

—in what was dubbed as the "Harmony Conference." The meeting led to the creation of the "National Agreement of Professional Base Ball Clubs" (sometimes referred to as the "Tripartite Agreement"), which stated that every league team would be entitled to reserve 11 players at the end of a season to play for their current team throughout the next year. Unsurprisingly, the agreement was unpopular with players, who organized to form a new league for the 1884 season, the Union Association

The Union Association was an American professional baseball league which competed with Major League Baseball, lasting for just the 1884 season. St. Louis won the pennant and joined the National League the following season.

Seven of the twelv ...

, which did not recognize the reserve rule or salary limitations. Mills reacted by threatening the defecting players with permanent expulsion and heavy fines, but many chose to leave anyway. Unfortunately, heavy financial losses and low attendance caused the UA and several participant teams to fold only after one season.

UA players later attempted to rejoin the NL, but Mills was particularly adamant about sticking to his word. In spite of Mills' objections, the league saw opportunity for boosting profits, and voted to allow the former UA players back in. In 1884, Mills resigned as league president, frustrated by yet another humiliating defeat of principle when Henry Lucas—none other than the founder of the UA—was voted back into the league as owner of a new St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

franchise. However, Mills continued to serve as an unofficial consultant on league matters.

The Mills Commission

In 1888, Spalding accompanied a group of star players on a world tour to promote the game of baseball, playing an exhibition game in the shadow of theGreat Pyramids

The Giza pyramid complex (also called the Giza necropolis) in Egypt is home to the Great Pyramid, the pyramid of Khafre, and the pyramid of Menkaure, along with their associated pyramid complexes and the Great Sphinx. All were built during the ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. Upon their return the following year, a dinner was held to honor the players and Mills was asked to serve as master of ceremonies. The dinner, held at Delmonico's Restaurant

Delmonico's is a series of restaurants that have operated in New York City, and Greenwich, Connecticut, with the present version located at 56 Beaver Street in the Financial District of Manhattan.

The original version was widely recogni ...

in New York, was attended by an eclectic and prestigious crowd of 300 guests, among them Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. The event's main theme focused on the sport as America's ambassador to the world. Also emphasized was the notion that baseball had not, as many believed, evolved from the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

game of rounders

Rounders is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams. Rounders is a striking and fielding team game that involves hitting a small, hard, leather-cased ball with a wooden, plastic, or metal bat that has a cylindrical end. The players score b ...

. Reportedly, at various points throughout the evening, audience members broke out into rousing chants of "No rounders! No rounders!". The display of patriotism intrigued Spalding and inspired a debate concerning baseball's origins. The debate came to a head in when Henry Chadwick published a widely read article tracing baseball's evolution from rounders. In response, Spalding, who believed baseball was a fundamentally American invention, published an article disputing Chadwick's claim and challenged him by suggesting that they appoint a commission to settle the matter. Chadwick agreed, and in a commission headed by Mills was formed.

The "Mills Commission" featured Mills and six other prominent men: Morgan G. Bulkeley, the NL's first president in 1876; Arthur P. Gorman

Arthur Pue Gorman (March 11, 1839June 4, 1906) was an American politician. He was leader of the Gorman-Rasin organization with Isaac Freeman Rasin that controlled the Maryland Democratic Party from the late 1870s until his death in 1906. Gorma ...

, a former player and ex-president of the Washington Base Ball Club; Nicholas E. Young, the first secretary and fifth president (replacing Mills) of the NL; Alfred J. Reach and George Wright, well known sporting goods distributors and two of the most famous players of their day; and James Edward Sullivan

James Edward Sullivan (18 November 1862 – 16 September 1914) was an American sports official of Irish descent. He was one of the founders of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) on Jan 21, 1888, serving as its secretary from 1889 until 1906 wh ...

, president of the Amateur Athletic Union

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) is an amateur sports organization based in the United States. A multi-sport organization, the AAU is dedicated exclusively to the promotion and development of amateur sports and physical fitness programs. It h ...

. The commission, through a series of nationally distributed publications, requested any American who had any knowledge concerning the origins of baseball to come forward. They received a response from a 71-year-old mining engineer from Denver, Colorado

Denver ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Consolidated city and county, consolidated city and county, the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous city of the U.S. state of ...

named Abner Graves, which was published immediately under the headline: "Abner Doubleday Invented Base Ball." According to Graves' account, Doubleday was responsible for improving a local version of "Town Ball" being played by students of the Otsego Academy and Green's Select School in Cooperstown, New York

Cooperstown is a village in and the county seat of Otsego County, New York, United States. Most of the village lies within the town of Otsego, but some of the eastern part is in the town of Middlefield. Located at the foot of Otsego Lake in ...

. Graves also claimed to witness the actual formation of the game which Doubleday termed "Base Ball." The commission did not investigate Graves' claim, however, and accepted the story on the basis that Graves' account offered the kind of mythical beginning to a sport they wanted to promote as fundamentally American. A number of circumstantial inconsistencies suggested that Graves' story was most likely fabricated. Despite all of the unanswered questions, Mills wrote a memo known as the "Mills Commission Report" that proclaimed Doubleday the inventor of the game of baseball. For over half a century prior to coming under the scrutiny of historians, it remained the authoritative document on the issue. However, it is now accepted that Chadwick was correct in his belief that baseball had in fact evolved from the game of rounders. Mills himself may have had some doubts concerning the validity of his own commission's findings and he admitted that he had had no conclusive evidence to prove the Doubleday claim.

Late career

The commission was Mills' last major role in professional baseball. Having long spent his career working for the Hale Elevator Company of Chicago, Mills became vice-president of one of its agents—theOtis Elevator Company

Otis Worldwide Corporation (trade name, branded as the Otis Elevator Company, its former legal name) styled as OTIS is an American company that develops, manufactures and markets

elevators, escalators, moving walkways, and related equipment.

...

—in 1898 and held the position until his death. In his later years, Mills was involved in amateur athletics, becoming the director and president of the New York Athletic Club

The New York Athletic Club is a Gentlemen's club, private social club and athletic club in New York (state), New York state. Founded in 1868, the club has approximately 8,600 members and two facilities: the City House, located at 180 Central Pa ...

and in 1921, penned the American Olympic Association constitution. At the time of his death in 1929 in Falmouth, Massachusetts

Falmouth ( ) is a New England town, town in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 32,517 at the 2020 census, making Falmouth the second-largest municipality on Cape Cod after Barnstable, Massachusetts, Barnstable. T ...

, he presided over the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks

The Adirondack Mountains ( ) are a massif of mountains in Northeastern New York (state), New York which form a circular dome approximately wide and covering about . The region contains more than 100 peaks, including Mount Marcy, which is the hi ...

, and was involved in planning the 1932 Winter Olympics

The 1932 Winter Olympics, officially known as the III Olympic Winter Games and commonly known as Lake Placid 1932, were a winter multi-sport event in the United States, held in Lake Placid, New York, United States. The games opened on February 4 ...

. He died on August 26, 1929, aged 85.

See also

*Origins of baseball

The question of the origins of baseball has been the subject of debate and controversy for more than a century. Baseball and the other modern bat, ball, and running games – stoolball, cricket and rounders – were developed from folk games in ...

References

*The Baseball Biography Project. Mallinson, JamesA. G. Mills

Retrieved Oct. 10, 2006.

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mills, Abraham 1844 births 1929 deaths Otis Worldwide Baseball executives National League presidents