Millbank Prison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

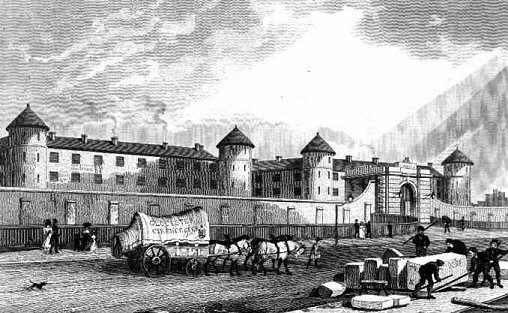

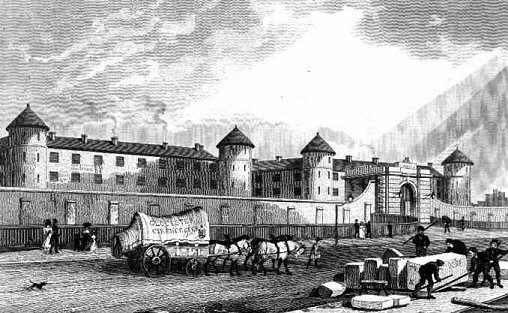

Millbank Prison or Millbank Penitentiary was a prison in

Millbank Prison or Millbank Penitentiary was a prison in

The site at Millbank was originally purchased in 1799 from the Marquess of Salisbury for £12,000 by the philosopher

The site at Millbank was originally purchased in 1799 from the Marquess of Salisbury for £12,000 by the philosopher

The plan of the prison comprised a circular chapel at the centre of the site, surrounded by a three-storey hexagon made up of the governor's quarters, administrative offices and laundries, surrounded in turn by six pentagons of cell blocks. The buildings of each pentagon were set around a cluster of five small courtyards (with a

The plan of the prison comprised a circular chapel at the centre of the site, surrounded by a three-storey hexagon made up of the governor's quarters, administrative offices and laundries, surrounded in turn by six pentagons of cell blocks. The buildings of each pentagon were set around a cluster of five small courtyards (with a

As the prison was progressively demolished its site was redeveloped. The principal new buildings erected were the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate Britain), which opened in 1897; the Royal Army Medical College, the buildings of which were adapted in 2005 to become the Chelsea College of Art & Design; andusing the original bricks of the prisonthe Millbank Estate, a housing estate built by the

As the prison was progressively demolished its site was redeveloped. The principal new buildings erected were the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate Britain), which opened in 1897; the Royal Army Medical College, the buildings of which were adapted in 2005 to become the Chelsea College of Art & Design; andusing the original bricks of the prisonthe Millbank Estate, a housing estate built by the

A large circular bollard stands by the river with the inscription: "Near this site stood Millbank Prison which was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. This buttress stood at the head of the river steps from which, until 1867, prisoners sentenced to transportation embarked on their journey to Australia."

Part of the perimeter ditch of the prison survives running between Cureton Street and John Islip Street. It is now used as a clothes-drying area for residents of Wilkie House.

Archaeological investigations in the late 1990s and early 2000s on the sites of Chelsea College of Art and Design and Tate Britain recorded significant remains of the foundations of the external pentagon walls of the prison, of parts of the inner hexagon, of two of the courtyard watchtowers, of drainage

A large circular bollard stands by the river with the inscription: "Near this site stood Millbank Prison which was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. This buttress stood at the head of the river steps from which, until 1867, prisoners sentenced to transportation embarked on their journey to Australia."

Part of the perimeter ditch of the prison survives running between Cureton Street and John Islip Street. It is now used as a clothes-drying area for residents of Wilkie House.

Archaeological investigations in the late 1990s and early 2000s on the sites of Chelsea College of Art and Design and Tate Britain recorded significant remains of the foundations of the external pentagon walls of the prison, of parts of the inner hexagon, of two of the courtyard watchtowers, of drainage

Collection of Victorian references

– the penitentiary is the distinctive six-pointed building near the bottom

Millbank Estate today

{{Prisons in London 1816 establishments in England Defunct prisons in London Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster Demolished buildings and structures in London Buildings and structures demolished in 1903 19th century in London 1890 disestablishments in England Millbank Demolished prisons

Millbank Prison or Millbank Penitentiary was a prison in

Millbank Prison or Millbank Penitentiary was a prison in Millbank

Millbank is an area of central London in the City of Westminster. Millbank is located by the River Thames, east of Pimlico and south of Westminster. Millbank is known as the location of major government offices, Burberry headquarters, the Mill ...

, Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, originally constructed as the National Penitentiary, and which for part of its history served as a holding facility for convicted prisoners before they were transported to Australia. It was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890.

Construction

The site at Millbank was originally purchased in 1799 from the Marquess of Salisbury for £12,000 by the philosopher

The site at Millbank was originally purchased in 1799 from the Marquess of Salisbury for £12,000 by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

, acting on behalf of the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

, for the erection of his proposed panopticon

The panopticon is a design of institutional building with an inbuilt system of control, originated by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. The concept is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be ...

prison as Britain's new National Penitentiary. After various changes in circumstance, the Panopticon plan was abandoned in 1812. Proposals for the National Penitentiary continued, however, and were given a legislative basis in the Penitentiary House, etc. Act 1812 ( 52 Geo. 3. c. 44). An architectural competition for a new prison building on the Millbank site attracted 43 entrants: the winning design was that of William Williams, drawing master at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC) was a United Kingdom, British military academy for training infantry and cavalry Officer (armed forces), officers of the British Army, British and British Indian Army, Indian Armies. It was founded in 1801 at Gre ...

. Williams' basic plan was adapted by a practising architect, Thomas Hardwick, who began construction in the same year.

The marshy site on which the prison stood meant that the builders experienced problems of subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

from the outset, and explains the succession of architects. It was to consist of a hexagonal central courtyard with an elongated pentagonal courtyard on each outer wall of the central courtyard; the three outer corners of the pentagonal courtyards each had a tower one storey higher than the three floors of the rest of the building. When the boundary wall reached a height of about six feet high it began to tilt and crack. After 18 months, with £26,000 spent on it, Hardwick resigned in 1813, and John Harvey took over the role. Harvey was dismissed in turn in 1815, and replaced by Robert Smirke, who brought the project to completion in 1821. Further legislation was passed in the form of the ( 56 Geo. 3. c. 63).

In February 1816 the first prisoners were admitted during the construction process, but the building creaked and several windows spontaneously shattered. Smirke and the engineer John Rennie the Elder were called in, and they recommended demolition of three of the towers and the underpinning of the entire building with concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of aggregate bound together with a fluid cement that cures to a solid over time. It is the second-most-used substance (after water), the most–widely used building material, and the most-manufactur ...

foundations, in form of a raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water. It is usually of basic design, characterized by the absence of a hull. Rafts are usually kept afloat by using any combination of buoyant materials such as wood, sealed barre ...

: the first known use of this material for foundations in Britain since the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. However, this added considerably to the construction costs, which eventually totalled £500,000, more than twice the original estimate and equivalent to £500 per cell.

History

The first prisoners, all women, were admitted on 26 June 1816. The first men arrived in January 1817. The prison held 103 men and 109 women by the end of 1817, and 452 men and 326 women by late 1822. Sentences of five to ten years in the National Penitentiary were offered as an alternative totransportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

to those thought most likely to reform.

In addition to the problems of construction, the marshy site fostered disease, to which the prisoners had little immunity owing to their extremely poor diet. In 1818 the authorities engaged Dr. Alexander Copland Hutchison of Westminster Dispensary as Medical Supervisor, to oversee the health of the inmates. In 1822–23 an epidemic swept through the prison, which seems to have comprised a mixture of dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

, scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

, depression and other disorders. The decision was eventually taken to evacuate the buildings for several months: the female prisoners were released, and the male prisoners temporarily transferred to the prison hulks at Woolwich, where their health improved.

The design of Millbank also turned out to be unsatisfactory. The network of corridors was so labyrinthine that even the warders got lost; and the ventilation system allowed sound to carry, so that prisoners could communicate between cells. The annual running costs turned out to be an unsupportable £16,000.

In view of these problems, the decision was eventually taken to build a new "model prison" at Pentonville, which opened in 1842 and took over Millbank's role as the National Penitentiary. By the ( 6 & 7 Vict. c. 26), Millbank's status was downgraded, and it became a holding depot for convicts prior to transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

. Every person sentenced to transportation was sent to Millbank first, where they were held for three months before their final destination was decided. By 1850, around 4,000 people were condemned annually to transportation from the UK. Prisoners awaiting transportation were kept in solitary confinement and restricted to silence for the first half of their sentence.

Large-scale transportation ended in 1853 (although the practice continued on a reduced scale until 1867); and Millbank then became an ordinary local prison, and from 1870 a military prison. By 1886 it had ceased to hold inmates, and it closed in 1890. Demolition began in 1892, and continued sporadically until 1903.

Description

watchtower

A watchtower or guardtower (also spelt watch tower, guard tower) is a type of military/paramilitary or policiary tower used for guarding an area. Sometimes fortified, and armed with heavy weaponry, especially historically, the structures are ...

at the centre) used as airing-yards, and in which prisoners undertook labour. The three outer angles of each pentagon were distinguished by tall circular towers, described in 1862 as " Martello-like": these served in part as watchtowers, but their primary purpose was to contain staircases and water-closets.Mayhew and Binny 1862. The third and fourth pentagons (those to the north-west, furthest from the entrance) were used to house female prisoners, and the remaining four for male prisoners.

In the ''Handbook of London'' in 1850 the prison was described as follows:

Each cell had a single window (looking into the pentagon courtyard), and was equipped with a washing tub, a wooden stool, a hammock and bedding, and books including a Bible, a prayer-book, a hymn-book, an arithmetic-book, a work entitled ''Home and Common Things'', and publications of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) is a United Kingdom, UK-based Christians, Christian charity. Founded in 1698 by Thomas Bray, it has worked for over 300 years to increase awareness of the Christians, Christian faith in the Un ...

.

Irish republican

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

prisoner Michael Davitt, who was held briefly at Millbank in 1870, described the experience:

Later development of the site

As the prison was progressively demolished its site was redeveloped. The principal new buildings erected were the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate Britain), which opened in 1897; the Royal Army Medical College, the buildings of which were adapted in 2005 to become the Chelsea College of Art & Design; andusing the original bricks of the prisonthe Millbank Estate, a housing estate built by the

As the prison was progressively demolished its site was redeveloped. The principal new buildings erected were the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate Britain), which opened in 1897; the Royal Army Medical College, the buildings of which were adapted in 2005 to become the Chelsea College of Art & Design; andusing the original bricks of the prisonthe Millbank Estate, a housing estate built by the London County Council

The London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today ...

(LCC) between 1897 and 1902. The estate comprises 17 buildings, each named after a distinguished painter, and is Grade II listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, H ...

.

Surviving remains

A large circular bollard stands by the river with the inscription: "Near this site stood Millbank Prison which was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. This buttress stood at the head of the river steps from which, until 1867, prisoners sentenced to transportation embarked on their journey to Australia."

Part of the perimeter ditch of the prison survives running between Cureton Street and John Islip Street. It is now used as a clothes-drying area for residents of Wilkie House.

Archaeological investigations in the late 1990s and early 2000s on the sites of Chelsea College of Art and Design and Tate Britain recorded significant remains of the foundations of the external pentagon walls of the prison, of parts of the inner hexagon, of two of the courtyard watchtowers, of drainage

A large circular bollard stands by the river with the inscription: "Near this site stood Millbank Prison which was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. This buttress stood at the head of the river steps from which, until 1867, prisoners sentenced to transportation embarked on their journey to Australia."

Part of the perimeter ditch of the prison survives running between Cureton Street and John Islip Street. It is now used as a clothes-drying area for residents of Wilkie House.

Archaeological investigations in the late 1990s and early 2000s on the sites of Chelsea College of Art and Design and Tate Britain recorded significant remains of the foundations of the external pentagon walls of the prison, of parts of the inner hexagon, of two of the courtyard watchtowers, of drainage culvert

A culvert is a structure that channels water past an obstacle or to a subterranean waterway. Typically embedded so as to be surrounded by soil, a culvert may be made from a pipe (fluid conveyance), pipe, reinforced concrete or other materia ...

s, and of Smirke's concrete raft.

The granite gate piers at the entrance of Purbeck House, High Street, Swanage

Swanage () is a coastal town and civil parish in the south east of Dorset, England. It is at the eastern end of the Isle of Purbeck and one of its two towns, approximately south of Poole and east of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester. In the Unit ...

in Dorset, and a granite bollard next to the gate, are thought by Historic England

Historic England (officially the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England) is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. It is tasked with prot ...

to be possibly from Millbank Prison.

Cultural references

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

describes the prison in chapter 52 ("Obstinacy") of his novel, ''Bleak House

''Bleak House'' is a novel by English author Charles Dickens, first published as a 20-episode Serial (literature), serial between 12 March 1852 and 12 September 1853. The novel has many characters and several subplots, and is told partly by th ...

'' (1852–53). One of the characters is put into custody there, and other characters go to visit him. Esther Summerson, one of the book's narrators, gives a brief description of its layout.

In Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

's realist novel '' The Princess Casamassima'' (1886) the prison is the "primal scene" of Hyacinth Robinson's life: the visit to his mother, dying in the infirmary, is described in chapter 3. James visited Millbank on 12 December 1884 to gain material.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

in chapter 8 of '' The Sign of Four'' (1890) refers to Holmes and Watson crossing the Thames from the house of Mordecai Smith and landing by the Millbank Penitentiary.

In chapter 8 of Conan Doyle's '' The Lost World'' (1912), Professor Challenger

George Edward Challenger is a fictional character in a series of fantasy and science fiction stories by Arthur Conan Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Unlike Doyle's self-controlled, analytical character, Sherlock Holmes, Professor Challenger is an ...

says that he dislikes walking along the Thames as it is always sad to see one's final destination. Challenger means that he expects to be buried at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, but his rival Professor Summerlee responds sardonically that he understands that Millbank Prison has been demolished.

The prison is a key location within Sarah Waters

Sarah Ann Waters (born 21 July 1966) is a Welsh novelist. She is best known for her novels set in Victorian society and featuring lesbian protagonists, such as '' Tipping the Velvet'' and '' Fingersmith''.

Life and education

Early life

Sara ...

' novel ''Affinity

Affinity may refer to:

Commerce, finance and law

* Affinity (law), kinship by marriage

* Affinity analysis, a market research and business management technique

* Affinity Credit Union, a Saskatchewan-based credit union

* Affinity Equity Pa ...

'' (1999).

The prison, Bentham's philosophy surrounding it, and a fictionalized account of Smirke's role in its construction play a key part in the plot of horror fiction podcast ''The Magnus Archives

''The Magnus Archives'' is a supernatural horror Podcast#Fiction_podcast, fiction podcast written by Jonathan Sims, directed by Alexander J. Newall, and distributed by Rusty Quill. Sims starred as the Head Archivist for the fictional Magnus Ins ...

'' (2016–2020) by Jonathan Sims.

See also

* List of demolished buildings and structures in London *Convicts in Australia

Between 1788 and 1868 the British penal system transported about 162,000 convicts from Great Britain and Ireland to various penal colonies in Australia.

The British Government began transporting convicts overseas to American colonies in t ...

*Penal transportation

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies bec ...

* Separate system

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * (Chapter 5). * '' The Nuttall Encyclopaedia'', "Millbank Prison". *External links

Collection of Victorian references

– the penitentiary is the distinctive six-pointed building near the bottom

Millbank Estate today

{{Prisons in London 1816 establishments in England Defunct prisons in London Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster Demolished buildings and structures in London Buildings and structures demolished in 1903 19th century in London 1890 disestablishments in England Millbank Demolished prisons