Militaristic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong

The roots of German militarism can be found in 18th- and 19th-century

The roots of German militarism can be found in 18th- and 19th-century

In parallel with 20th-century German militarism, Japanese militarism began with a series of events by which the military gained prominence in dictating Japan's affairs. This was evident in 15th-century Japan's ''Sengoku'' period or ''Age of Warring States'', where powerful

In parallel with 20th-century German militarism, Japanese militarism began with a series of events by which the military gained prominence in dictating Japan's affairs. This was evident in 15th-century Japan's ''Sengoku'' period or ''Age of Warring States'', where powerful

In the pre-colonial era, the

In the pre-colonial era, the

Russia has also had a long history of militarism continuing on to the present day driven by its desire to protect its western frontier which has no natural buffers between potential invaders from the rest of continental Europe and her heartlands in European Russia. Ever since

Russia has also had a long history of militarism continuing on to the present day driven by its desire to protect its western frontier which has no natural buffers between potential invaders from the rest of continental Europe and her heartlands in European Russia. Ever since

The first military coup in the history of the republic was on 27 May 1960, which resulted in the hanging of PM

The first military coup in the history of the republic was on 27 May 1960, which resulted in the hanging of PM

During this time the ideas of

During this time the ideas of

Militarism in Venezuela follows the cult and myth of

Militarism in Venezuela follows the cult and myth of

The history of

The history of

By 1990,

By 1990,

Wars, Internal Conflicts and Political Order

'' Albany: State University of New York Press. 1996. * Bond, Brian. ''War and Society in Europe, 1870–1970.'' McGill-Queen's University Press. 1985 * Conversi, Daniele 2007 'Homogenisation, nationalism and war’

Nations and Nationalism

Vol. 13, no 3, 2007, pp. 1–24 * Ensign, Tod. ''America's Military Today.'' The New Press. 2005. . * Fink, Christina. ''Living Silence: Burma Under Military Rule.'' White Lotus Press. 2001. . * Freedman, Lawrence, ''Command: The Politics of Military Operations from Korea to Ukraine'',

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the military and of the ideals of a professional military class and the "predominance of the armed forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a ...

in the administration or policy of the state" (see also: stratocracy

A stratocracy is a list of forms of government, form of government headed by military chiefs. The Separation of powers, branches of government are administered by military forces, the government is legal under the laws of the jurisdiction at issu ...

and military junta

A military junta () is a system of government led by a committee of military leaders. The term ''Junta (governing body), junta'' means "meeting" or "committee" and originated in the Junta (Peninsular War), national and local junta organized by t ...

).

Militarism has been a significant element of the imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

or expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who ...

ideologies of many nations throughout history. Notable ancient examples include the Assyrian Empire

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, an indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

** Post-im ...

, the Greek city state of Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, the Aztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

nation, and the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

. Examples from modern times include the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

/German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

/Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

monarchy, the First French Empire

The First French Empire or French Empire (; ), also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. It lasted from ...

, the Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom ( ; ), sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large following which ruled a wide expanse of So ...

, the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

, the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

under Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

, and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

/Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

/Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

.

By nation

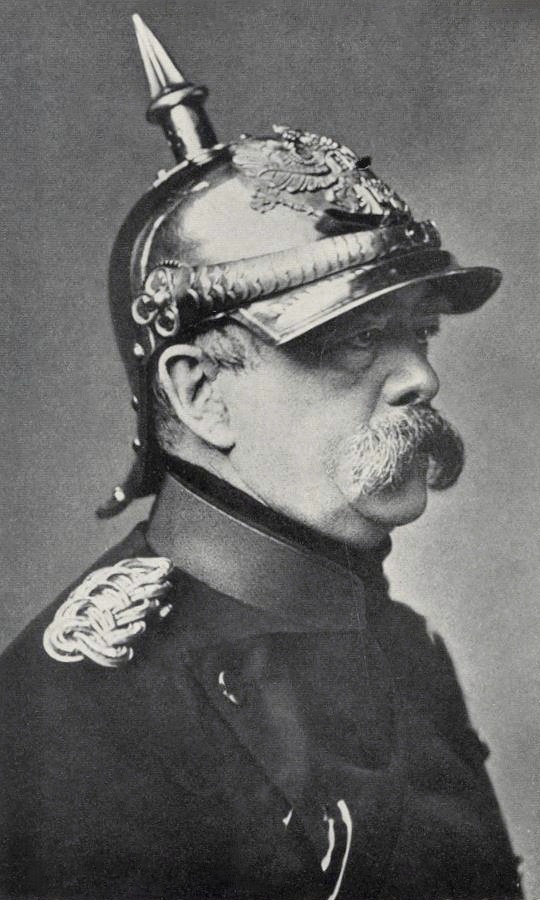

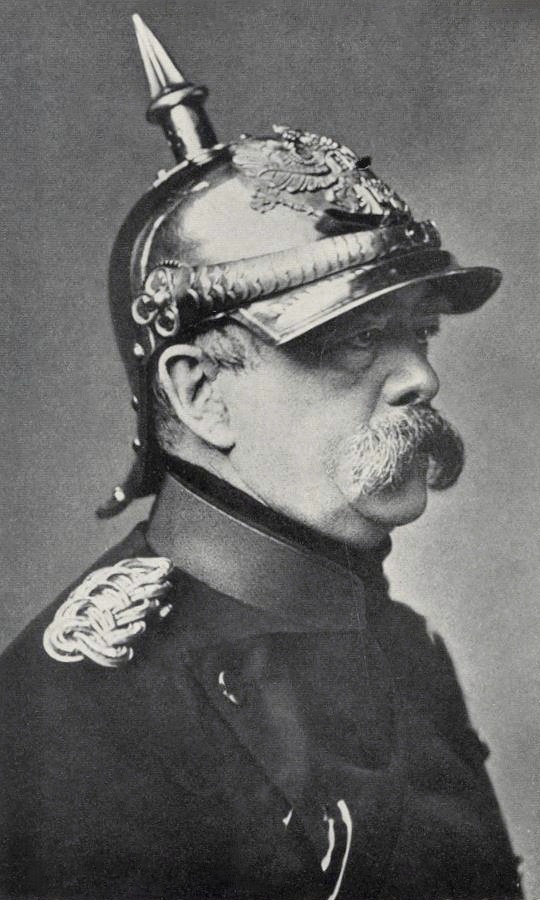

Germany

The roots of German militarism can be found in 18th- and 19th-century

The roots of German militarism can be found in 18th- and 19th-century Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

and the subsequent unification of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

under Prussian leadership. However, Hans Rosenberg sees its origin already in the Teutonic Order

The Teutonic Order is a religious order (Catholic), Catholic religious institution founded as a military order (religious society), military society in Acre, Israel, Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Sa ...

and its colonization of Prussia during the late Middle Ages, when mercenaries from the Holy Roman Empire were granted lands by the Order and gradually formed a new landed militarist Prussian nobility, from which the Junker

Junker (, , , , , , ka, იუნკერი, ) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German , meaning 'young nobleman'Duden; Meaning of Junker, in German/ref> or otherwise 'young lord' (derivation of and ). The term is traditionally ...

nobility would later evolve.

During the 17th-century reign of the "Great Elector" Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg

Frederick William (; 16 February 1620 – 29 April 1688) was Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia, thus ruler of Brandenburg-Prussia, from 1640 until his death in 1688. A member of the House of Hohenzollern, he is popularly known as "th ...

, Brandenburg-Prussia increased its military to 40,000 men and began an effective military administration overseen by the General War Commissariat. In order to bolster his power both in interior and foreign matters, so-called ''Soldatenkönig'' ("soldier king") Frederick William I of Prussia

Frederick William I (; 14 August 1688 – 31 May 1740), known as the Soldier King (), was King in Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg from 1713 until his death in 1740, as well as Prince of Neuchâtel.

Born in Berlin, he was raised by the Hugu ...

started his large-scale military reforms in 1713, thus beginning the country's tradition of a high military budget by increasing the annual military spending to 73% of the entire annual budget of Prussia. By the time of his death in 1740, the Prussian Army had grown into a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars ...

of 83,000 men, one of the largest in Europe, at a time when the entire Prussian populace made up 2.5 million people. Prussian military writer Georg Henirich von Berenhorst would later write in hindsight that ever since the reign of the ''soldier king'', Prussia always remained "not a country with an army, but an army with a country" (a quote often misattributed to Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

and Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Count of Mirabeau (; 9 March 17492 April 1791) was a French writer, orator, statesman and a prominent figure of the early stages of the French Revolution.

A member of the nobility, Mirabeau had been involved in numerous ...

).

After Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

defeated Prussia in 1806, one of the conditions of peace was that Prussia should reduce its army to no more than 42,000 men. Since the time of Frederick The Great

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself ''King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prussia ...

, however, Prussia practiced the Kruemper System, formed by dismissing a number of trained men at regular intervals and replacing them with raw recruits, thereby passing a large number of men through the ranks. The officers of the army were drawn almost entirely from among the land-owning nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

. The result was that there was gradually built up a large class of professional officers on the one hand, and a much larger class, the rank and file of the army, on the other. These enlisted men had become conditioned to obey implicitly all the commands of the officers, creating a class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

-based culture of deference

Deference (also called submission or passivity) is the condition of submitting to the espoused, legitimate influence of one's superior or superiors. Deference implies a yielding or submitting to the judgment of a recognized superior, out of re ...

.

This system led to several consequences. Since the officer class also furnished most of the officials for the civil administration of the country, the interests of the army came to be considered as identical to the interests of the country as a whole. In the 1900s militant monarchism was highly developed, garnering a fan-base in the United States of America. Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

had his palace guard dress in 37 different uniforms, including one that resampled the accessory worn by Frederick the Great. Wilhelm II appeared deluded about his physical disability, including his withered arm. He had sacked Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

in 1890 and obtained near absolute power but had to accept Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (; 9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general and politician. He achieved fame during World War I (1914–1918) for his central role in the German victories at Battle of Liège, Liège and Battle ...

as chief policy maker. Army general Ludendorff was appointed director of the Reich in 1917 and exercised the constitutional powers of Wilhelm II.

Militarism in Germany continued after World War I and the fall of the German monarchy in the German Revolution of 1918–1919

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, in spite of Allied attempts to crush German militarism by means of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

, as the Allies saw Prussian and German militarism as one of the major causes of the Great War. During the period of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

(1918–1933), the 1920 Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an abortive coup d'état against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to ...

, an attempted coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

against the republican government, was launched by disaffected members of the armed forces. After this event, some of the more radical militarists and nationalists were submerged in grief and despair into the NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor, the German Workers ...

party of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

, while more moderate elements of militarism declined and remained affiliated with the German National People's Party

The German National People's Party (, DNVP) was a national-conservative and German monarchy, monarchist political party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major nationalist party in Weimar German ...

(DNVP) instead.

Throughout its entire 14-year existence, the Weimar Republic remained under threat of militaristic nationalism, as many Germans felt the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

humiliated their militaristic culture. The Weimar years saw large-scale right-wing militarist and paramilitary mass organizations such as '' Der Stahlhelm'' as well as militias such as the ''Freikorps'', which was banned in 1921. In the same year, the ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' (; ) was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first two years of Nazi Germany. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

'' set up the Black Reichswehr

The Black Reichswehr () was the unofficial name for the extra-legal paramilitary formation that was secretly a part of the German military ( Reichswehr) during the early years of the Weimar Republic. It was formed in 1921 after the German govern ...

, a secret reserve of trained soldiers networked within its units organised as "labour battalions" (''Arbeitskommandos'') to circumvent the Treaty of Versailles' 100,000 man limit on the German army.; it was dissolved in 1923. Many members of the ''Freikorps'' and the Black Reichswehr went on to join the ''Sturmabteilung

The (; SA; or 'Storm Troopers') was the original paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party of Germany. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power, Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and early 1930s. I ...

'' (SA), the paramilitary branch of the Nazi party. All of these were responsible for the political violence of so-called ''Feme'' murders and an overall atmosphere of lingering civil war during the Weimar period. During the Weimar era, mathematician and political writer Emil Julius Gumbel

Emil Julius Gumbel (18 July 1891, in Munich – 10 September 1966, in New York City) was a German mathematician and political writer.

Gumbel specialised in mathematical statistics and, along with Leonard Tippett and Ronald Fisher, was instrum ...

published in-depth analyses of the militarist paramilitary violence characterizing German public life as well as the state's lenient to sympathetic reaction to it if the violence was committed by the political right.

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

was a strongly militarist state; after its defeat in 1945, militarism in German culture was dramatically reduced as a backlash against the Nazi period, and the Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council (ACC) or Allied Control Authority (), also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allies of World War II, Allied Allied-occupied Germany, occupation zones in Germany (1945–1949/1991) and Al ...

and later the Allied High Commission

The Allied High Commission (also known as the High Commission for Occupied Germany, HICOG; in German ''Alliierte Hohe Kommission'', ''AHK'') was established by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France after the 1948 breakdown of the Alli ...

oversaw a program of attempted fundamental re-education of the German people at large in order to put a stop to German militarism once and for all.

The Federal Republic of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen constituent states have a total population of over 84 ...

today maintains a large, modern military and has one of the highest defence budgets in the world; at 1.3 percent of Germany's GDP, it is, in 2019, similar in cash terms to those of the United Kingdom, France and Japan, at around US$50bn.

India

The rise of militarism in India dates back to theBritish Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

with the establishment of several Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

organizations such as the Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA, sometimes Second INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a Empire of Japan, Japanese-allied and -supported armed force constituted in Southeast Asia during World War II and led by Indian Nationalism#An ...

led by Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose (23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945) was an Indian independence movement, Indian nationalist whose defiance of British raj, British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians, but his wartime alliances with ...

. The Indian National Army (INA) played a crucial role in pressuring the British Raj after it occupied the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands is a union territory of India comprising 572 islands, of which only 38 are inhabited. The islands are grouped into two main clusters: the northern Andaman Islands and the southern Nicobar Islands, separated by a ...

with the help of Imperial Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

, but the movement lost momentum due to lack of support by the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

, the Battle of Imphal

The Battle of Imphal () took place in the region around the city of Imphal, the capital of the state of Manipur in Northeast India from March until July 1944. Empire of Japan, Japanese armies attempted to destroy the Allied forces at Imphal and ...

, and Bose's sudden death.

After India gained independence in 1947, tensions with neighbouring Pakistan over the Kashmir dispute and other issues led the Indian government to emphasize military preparedness (see also the political integration of India

Before it gained independence in 1947, India (also called the Indian Empire) was divided into two sets of territories, one under direct British rule (British India), and the other consisting of princely states under the suzerainty of the Briti ...

). After the Sino-Indian War

The Sino–Indian War, also known as the China–India War or the Indo–China War, was an armed conflict between China and India that took place from October to November 1962. It was a military escalation of the Sino–Indian border dispu ...

in 1962, India dramatically expanded its military which helped India win the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. India became the third Asian country in the world to possess nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (thermonuclear weap ...

, culminating in the tests of 1998. The Kashmiri insurgency and recent events including the Kargil War

The Kargil War, was fought between India and Pakistan from May to July 1999 in the Kargil district of Ladakh, then part of the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir (state), Jammu and Kashmir and along the Line of Control (LoC). In In ...

against Pakistan, assured that the Indian government remained committed to military expansion. The disputed Jammu and Kashmir territory in India is regarded as one of the world’s most militarized places.

In recent years, the Indian government has increased the military expenditure of the 1.4 million-strong military across all branches and embarked on a rapid modernization program.

Japan

In parallel with 20th-century German militarism, Japanese militarism began with a series of events by which the military gained prominence in dictating Japan's affairs. This was evident in 15th-century Japan's ''Sengoku'' period or ''Age of Warring States'', where powerful

In parallel with 20th-century German militarism, Japanese militarism began with a series of events by which the military gained prominence in dictating Japan's affairs. This was evident in 15th-century Japan's ''Sengoku'' period or ''Age of Warring States'', where powerful samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

warlords (''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and no ...

s'') played a significant role in Japanese politics. Japan's militarism is deeply rooted in the ancient samurai tradition, centuries before Japan's modernization. Even though a militarist philosophy was intrinsic to the shogunates, a nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

style of militarism developed after the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

, which restored the Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

to power and began the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

. It is exemplified by the 1882 Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors

The was the official code of ethics for military personnel, and is often cited along with the ''Imperial Rescript on Education'' as the basis for Japan's pre-World War II national ideology. All military personnel were required to memorize the 2 ...

, which called for all members of the armed forces to have an absolute personal loyalty to the Emperor.

In the 20th century (approximately in the 1920s), two factors contributed both to the power of the military and chaos within its ranks. One was the "Military Ministers to be Active-Duty Officers Law", which required the Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

(IJA) and Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

(IJN) to agree to the Ministry of Army position in the Cabinet. This essentially gave the military veto power over the formation of any Cabinet in the ostensibly parliamentary country. Another factor was '' gekokujō'', or institutionalized disobedience by junior officers. It was not uncommon for radical junior officers to press their goals, to the extent of assassinating their seniors. In 1936, this phenomenon resulted in the February 26 Incident, in which junior officers attempted a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

and killed leading members of the Japanese government. The rebellion enraged Emperor Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

and he ordered its suppression, which was successfully carried out by loyal members of the military.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

damaged Japan's economy and gave radical elements within the Japanese military the chance to realize their ambitions of conquering all of Asia. In 1931, the Kwantung Army

The Kwantung Army (Japanese language, Japanese: 関東軍, ''Kantō-gun'') was a Armies of the Imperial Japanese Army, general army of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1919 to 1945.

The Kwantung Army was formed in 1906 as a security force for th ...

(a Japanese military force stationed in Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

) staged the Mukden Incident, which sparked the Invasion of Manchuria and its transformation into the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially known as the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of Great Manchuria thereafter, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China that existed from 1932 until its dissolution in 1945. It was ostens ...

. Six years later, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident outside Peking

Beijing, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's most populous national capital city as well as China's second largest city by urban area after Shanghai. It is l ...

sparked the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

(1937–1945). Japanese troops streamed into China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, conquering Peking, Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, and the national capital of Nanking

Nanjing or Nanking is the capital of Jiangsu, a province in East China. The city, which is located in the southwestern corner of the province, has 11 districts, an administrative area of , and a population of 9,423,400.

Situated in the Yan ...

; the last conquest was followed by the Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre, or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians, noncombatants, and surrendered prisoners of war by the Imperial Japanese Army in Nanjing, the capital of the Republ ...

. In 1940, Japan entered into an alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or sovereign state, states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an a ...

with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

, two similarly militaristic states in Europe, and advanced out of China and into Southeast Asia. The following year, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor to prevent the intervention of the United States, which had banned oil sales to Japan in response to the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

and the ensuing invasion of Indochina.

In 1945, Japan surrendered to the United States, beginning the Occupation of Japan

Japan was occupied and administered by the Allies of World War II from the surrender of the Empire of Japan on September 2, 1945, at the war's end until the Treaty of San Francisco took effect on April 28, 1952. The occupation, led by the ...

and the purging of all militarist influences from Japanese society and politics. In 1947, the new Constitution of Japan

The Constitution of Japan is the supreme law of Japan. Written primarily by American civilian officials during the occupation of Japan after World War II, it was adopted on 3 November 1946 and came into effect on 3 May 1947, succeeding the Meij ...

supplanted the Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan ( Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in ...

as the fundamental law of the country, replacing the rule of the Emperor with parliamentary government. With this event, the Empire of Japan officially came to an end and the modern State of Japan was founded.

North Korea

''Sŏn'gun'' (often transliterated "songun"),North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

's "Military First" policy, regards military power as the highest priority of the country. This has escalated so much in the DPRK that one in five people serves in the armed forces, and the military has become one of the largest in the world.

''Songun'' elevates the Korean People's Armed Forces within North Korea as an organization and as a state function, granting it the primary position in the North Korean government

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

and society. The principle guides domestic policy

Domestic policy, also known as internal policy, is a type of public policy overseeing administrative decisions that are directly related to all issues and activity within a state's borders. It differs from foreign policy, which refers to the ways ...

and international interactions.

It provides the framework of the government, designating the military as the "supreme repository of power". It also facilitates the militarization of non-military sectors by emphasizing the unity of the military and the people by spreading military culture among the masses. The North Korean government grants the Korean People's Army

The Korean People's Army (KPA; ) encompasses the combined military forces of North Korea and the armed wing of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK). The KPA consists of five branches: the Korean People's Army Ground Force, Ground Force, the Ko ...

as the highest priority in the economy and in resource-allocation, and positions it as the model for society to emulate.

''Songun'' is also the ideological

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

concept behind a shift in policies (since the death of Kim Il Sung

Kim Il Sung (born Kim Song Ju; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he led as its first Supreme Leader (North Korean title), supreme leader from North Korea#Founding, its establishm ...

in 1994) which emphasize the people's military over all other aspects of state and the interests of the military comes first before the masses (workers).

Philippines

In the pre-colonial era, the

In the pre-colonial era, the Filipino people

Filipinos () are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. Filipinos come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino language, Filipino, Philippine English, English, or other Philippine language ...

had their own forces, divided between the islands which each had its own ruler. They were called ''Sandig'' ( Guards), ''Kawal'' (Knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

), and ''Tanod''. They also served as the police and watchers on the land, coastlines and seas. In 1521, the Visayan king of Mactan ''Lapu-Lapu

Lapulapu (fl. 1521) or Lapu-Lapu, whose name was first recorded as Çilapulapu, was a datu (chief) of Mactan, an island now part of the Philippines. Lapulapu is known for the 1521 Battle of Mactan, where he and his men defeated Spanish forc ...

'' of Cebu

Cebu ( ; ), officially the Province of Cebu (; ), is a province of the Philippines located in the Central Visayas region, and consists of a main island and 167 surrounding islands and islets. The coastal zone of Cebu is identified as a ...

, organized the first recorded military action against the Spanish colonizers, in the Battle of Mactan

The Battle of Mactan (; ) was fought on a beach in Mactan Island (now part of Cebu, Philippines) between Spanish forces led by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan along with local allies, and Lapulapu, the chieftain of the island, on th ...

.

In the 19th century during the Philippine Revolution

The Philippine Revolution ( or ; or ) was a war of independence waged by the revolutionary organization Katipunan against the Spanish Empire from 1896 to 1898. It was the culmination of the 333-year History of the Philippines (1565–1898), ...

, Andrés Bonifacio

Andrés Bonifacio y de Castro (, ; November 30, 1863May 10, 1897) was a Filipino people, Filipino revolutionary leader. He is often called "The Father of the Philippines, Philippine Philippine Revolution, Revolution", and considered a nationa ...

founded the Katipunan

The Katipunan (), officially known as the (; ) and abbreviated as the KKK, was a revolutionary organization founded in 1892 by a group of Filipino nationalists Deodato Arellano, Andrés Bonifacio, Valentin Diaz, Ladislao Diwa, José Dizon, an ...

, a revolutionary organization against Spain at the Cry of Pugad Lawin

The Cry of Pugad Lawin (, ) was the beginning of the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire.

In late August 1896, members of the Katipunan led by Andrés Bonifacio revolted somewhere around Caloocan, which included parts of the pre ...

. Some notable battles were the Siege of Baler

The siege of Baler (; ) was a battle of the Philippine Revolution. Filipino revolutionaries laid siege to a fortified church defended by Spanish troops in the town of Baler, Aurora, for 337 days, from 1 July 1898 until 2 June 1899. The Spanish� ...

, the Battle of Imus

The Battle of Imus (, ), or the Siege of Imus (, ), was the first major battle of the Philippine revolution against the Spanish colonial government in the province of Cavite. It was fought between September 1–3, 1896 at Imus, Cavite provinc ...

, Battle of Kawit, Battle of Nueva Ecija, the victorious Battle of Alapan

The Battle of Alapan (, ) was fought on May 28, 1898, and was the first military victory of the Filipino Revolutionaries led by Emilio Aguinaldo after his return to the Philippines from Hong Kong. After the American naval victory in the Battle ...

and the famous Twin Battles of Binakayan and Dalahican. During Independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

, the President General Emilio Aguinaldo

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (: March 22, 1869February 6, 1964) was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who became the first List of presidents of the Philippines, president of the Philippines (1899–1901), and the first pre ...

established the '' Magdalo'', a faction separate from ''Katipunan

The Katipunan (), officially known as the (; ) and abbreviated as the KKK, was a revolutionary organization founded in 1892 by a group of Filipino nationalists Deodato Arellano, Andrés Bonifacio, Valentin Diaz, Ladislao Diwa, José Dizon, an ...

'', and he declared the revolutionary government in the constitution of the First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Republic (), now officially remembered as the First Philippine Republic and also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was a state established in Malolos, Bulacan, during the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish ...

.

During the Filipino-American War, the General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Antonio Luna

Antonio Narciso Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta (; October 29, 1866 – June 5, 1899) was a Filipinos, Filipino army general and a pharmacist who fought in the Philippine–American War before his assassination on June 5, 1899, at the age ...

as a high-ranking general, he ordered a conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

to all citizens, a mandatory form of national service (at any war) for the increase the density and the manpower of the Philippine Army

The Philippine Army (PA) () is the main, oldest and largest branch of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), responsible for ground warfare. , it had an estimated strength of 143,100 soldiers The service branch was established on December ...

.

During the World War II, the Philippines was one of the participants, as a member of Allied forces, the Philippines with the U.S. forces fought the Imperial Japanese Army (1942–1945), one of the notable battles is the victorious Battle of Manila, which also called "The Liberation".

During the 1970s the President Ferdinand Marcos

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr. (September 11, 1917 – September 28, 1989) was a Filipino lawyer, politician, dictator, and Kleptocracy, kleptocrat who served as the tenth president of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. He ruled the c ...

declared P.D.1081 or martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

, which also made the Philippines a garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

state. By the Philippine Constabulary

The Philippine Constabulary (PC; , ''HPP''; ) was a gendarmerie-type military police force of the Philippines from 1901 to 1991, and the predecessor to the Philippine National Police. It was created by the Insular Government, American occupat ...

(PC) and Integrated National Police

The Integrated National Police (INP) ( Filipino: ''Pinagsamang Pulisyáng Pambansà'', ''PPP''; Spanish: ''Policía Nacional Conjunta'', ''PNC'') was the municipal police force for the cities and large towns of the Republic of the Philippine ...

(INP), the high school or secondary and college education have a compulsory curriculum concerning the military, and nationalism which is the "Citizens Military Training" (CMT) and "Reserve Officers Training Corps" (ROTC).

But in 1986, when the constitution changed, this form of national service training program became non-compulsory but still part of the basic education.

Russia

Russia has also had a long history of militarism continuing on to the present day driven by its desire to protect its western frontier which has no natural buffers between potential invaders from the rest of continental Europe and her heartlands in European Russia. Ever since

Russia has also had a long history of militarism continuing on to the present day driven by its desire to protect its western frontier which has no natural buffers between potential invaders from the rest of continental Europe and her heartlands in European Russia. Ever since Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

's reforms, Russia became one of Europe's great powers in terms of political and military strength. Through the Imperial era, Russia continued on her quest for territorial expansion into Siberia, Caucasus and into Eastern Europe, eventually conquering the majority of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The end of imperial rule in 1917 meant the loss of some territory following the treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

, but much of it was quickly reconquered by the Soviet Union later on, including events such as the partition of Poland and reconquest of the Baltic states in the late 1930s and ‘40s. Soviet influence reached its peak after WWII in the Cold War era, during which the Soviet Union occupied virtually all of Eastern Europe in a military alliance known as the Warsaw Pact, with the Soviet Army playing a key role. All this was lost with the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

in 1991. Russia was greatly weakened in what Russia's second President Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

called the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century. Nevertheless, under Putin's leadership, a resurgent modern Russia has maintained a tremendous amount of geopolitical influence in the countries spawned from the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and modern Russia remains Eastern Europe's leading, if not dominant, power.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

, the Russian government increased their efforts to introduce "patriotic education" into schools. The Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

reported that some parents were shocked by the militaristic nature of the Kremlin-promoted '' Important Conversations'' lessons, with some comparing them to the "patriotic education" of the former Soviet Union.

By the end of 2023, Vladimir Putin planned to spend almost 40% of public expenditures on defense and security. UK Chief of Defence Staff Admiral Tony Radakin

Admiral (Royal Navy), Admiral Sir Antony David Radakin, (born 10 November 1965) is a senior Royal Navy officer. He was appointed Chief of the Defence Staff (United Kingdom), Chief of the Defence Staff, the professional head of the British Armed ...

said that "the last time we saw these levels was at the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union."

Turkey

Militarism has a long history inTurkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

.

The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

lasted for centuries and always relied on its military might, but militarism was not a part of everyday life. Militarism was only introduced into daily life with the advent of modern institutions, particularly schools, which became part of the state apparatus when the Ottoman Empire was succeeded by a new nation state – the Republic of Turkey – in 1923. The founders of the republic were determined to break with the past and modernise the country. There was, however, an inherent contradiction in that their modernist vision was limited by their military roots. The leading reformers were all military men and, in keeping with the military tradition, all believed in the authority and the sacredness of the state. The public also believed in the military. It was the military, after all, who led the nation through the War of Liberation (1919–1923) and saved the motherland.Adnan Menderes

Ali Adnan Ertekin Menderes (; 1899 – 17 September 1961) was a Turkish politician who served as Prime Minister of Turkey between 1950 and 1960. He was one of the founders of the Democrat Party (DP) in 1946, the fourth legal opposition party of ...

and 2 ministers, and a new constitution was introduced, creating a Constitutional Court to vet the legislation passed by parliament, and a military-dominated National Security Council to oversee the government affairs similar to the ''politburo'' in the Soviet Union. The second military coup took place on 12 March 1971, this time only forcing the government to resign and installing a cabinet of technocrats and bureaucrats without dissolving the parliament. The third military coup took place on 12 September 1980, which resulted in the dissolution of parliament and all political parties as well as imposition of a much more authoritarian constitution. There was another military intervention that was called a "post-modern coup" on 28 February 1997 which merely forced the government to resign, and finally an unsuccessful military coup attempt on 15 July 2016.

The constitutional referendums in 2010

The year saw a multitude of natural and environmental disasters such as the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and the 2010 Chile earthquake. The 2009 swine flu pandemic, swine flu pandemic which began the previous year ...

and 2017

2017 was designated as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development by the United Nations General Assembly.

Events January

* January 1 – Istanbul nightclub shooting: A gunman dressed as Santa Claus opens fire at the ...

have changed the composition and role of the National Security Council, and placed the armed forces under the control of civilian government.

United States

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries political and military leaders reformed the US federal government to establish a stronger central government than had ever previously existed for the purpose of enabling the nation to pursue an imperial policy in the Pacific and in the Caribbean and economic militarism to support the development of the new industrial economy. This reform was the result of a conflict between Neo-Hamiltonian Republicans and Jeffersonian- Jacksonian Democrats over the proper administration of the state and direction of its foreign policy. The conflict pitted proponents of professionalism, based on business management principles, against those favoring more local control in the hands of laymen and political appointees. The outcome of this struggle, including a more professional federal civil service and a strengthened presidency and executive branch, made a more expansionist foreign policy possible. After the end of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

the national army fell into disrepair. Reforms based on various European states including Britain, Germany, and Switzerland were made so that it would become responsive to control from the central government, prepared for future conflicts, and develop refined command and support structures; these reforms led to the development of professional military thinkers and cadre.

social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

helped propel American overseas expansion in the Pacific and Caribbean. This required modifications for a more efficient central government due to the added administration requirements (see above).

The enlargement of the U.S. Army for the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

was considered essential to the occupation and control of the new territories acquired from Spain in its defeat (Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, and Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

). The previous limit by legislation of 24,000 men was expanded to 60,000 regulars in the new army bill on 2 February 1901, with allowance at that time for expansion to 80,000 regulars by presidential discretion at times of national emergency.

U.S. forces were again enlarged immensely for World War I. Officers such as George S. Patton were permanent captains at the start of the war and received temporary promotions to colonel.

Between the first and second world wars, the US Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the Marines, maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expedi ...

engaged in questionable activities in the Banana Wars

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and Interventionism (politics), intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American W ...

in Latin America. Retired Major General Smedley Butler

Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940) was a United States Marine Corps officer and writer. During his 34-year military career, he fought in the Philippine–American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, ...

, who was at the time of his death the most decorated Marine, spoke strongly against what he considered to be trends toward fascism and militarism. Butler briefed Congress on what he described as a Business Plot

The Business Plot, also called the Wall Street Putsch and the White House Putsch, was a political conspiracy in 1933 in the United States to overthrow the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and install Smedley Butler as dictator. But ...

for a military coup, for which he had been suggested as leader; the matter was partially corroborated, but the real threat has been disputed. The Latin American expeditions ended with Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's Good Neighbor policy of 1934.

After World War II, there were major cutbacks, such that units responding early in the Korean War under United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

authority (e.g. Task Force Smith) were unprepared, resulting in catastrophic performance. When Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

fired Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

, the tradition of civilian control held and MacArthur left without any hint of military coup.

The Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

resulted in serious permanent military buildups. Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, a retired top military commander elected as a civilian president, warned, as he was leaving office, of the development of a military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the Arms industry, defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving fac ...

. In the Cold War, there emerged many civilian academics and industrial researchers, such as Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

and Herman Kahn

Herman Kahn (February 15, 1922 – July 7, 1983) was an American physicist and a founding member of the Hudson Institute, regarded as one of the preeminent futurists of the latter part of the twentieth century. He originally came to prominence ...

, who had significant input into the use of military force. The complexities of nuclear strategy and the debates surrounding them helped produce a new group of 'defense intellectuals' and think tanks, such as the Rand Corporation

The RAND Corporation, doing business as RAND, is an American nonprofit global policy think tank, research institute, and public sector consulting firm. RAND engages in research and development (R&D) in several fields and industries. Since the ...

(where Kahn, among others, worked).

It has been argued that the United States has shifted to a state of neomilitarism since the end of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. This form of militarism is distinguished by the reliance on a relatively small number of volunteer fighters; heavy reliance on complex technologies; and the rationalization and expansion of government advertising and recruitment programs designed to promote military service. President Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who was the 46th president of the United States from 2021 to 2025. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as the 47th vice p ...

signed a record $886 billion defense spending bill into law on December 22, 2023.

Venezuela

Militarism in Venezuela follows the cult and myth of

Militarism in Venezuela follows the cult and myth of Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24July 178317December 1830) was a Venezuelan statesman and military officer who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bol ...

, known as the liberator of Venezuela. For much of the 1800s, Venezuela was ruled by powerful, militarist leaders known as ''caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; , from Latin language, Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of Personalist dictatorship, personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise English translation for the term, though it ...

s''. Between 1892 and 1900 alone, six rebellions occurred and 437 military actions were taken to obtain control of Venezuela. With the military controlling Venezuela for much of its history, the country practiced a "military ethos

''Ethos'' is a Greek word meaning 'character' that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology; and the balance between caution and passion. The Greeks also used this word to refer to the ...

", with civilians today still believing that military intervention in the government is positive, especially during times of crisis, with many Venezuelans believing that the military opens democratic opportunities instead of blocking them.

Much of the modern political movement behind the Fifth Republic of Venezuela, ruled by the Bolivarian government established by Hugo Chávez

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (; ; 28 July 1954 – 5 March 2013) was a Venezuelan politician, Bolivarian Revolution, revolutionary, and Officer (armed forces), military officer who served as the 52nd president of Venezuela from 1999 until De ...

, was built on the following of Bolívar and such militaristic ideals.

Syria

The history of

The history of Syrian

Syrians () are the majority inhabitants of Syria, indigenous to the Levant, most of whom have Arabic, especially its Levantine and Mesopotamian dialects, as a mother tongue. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend ...

militarism begins in 1963, when the army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

staged a military coup against the democratically elected president Nazim al-Qudsi and brought the Ba'ath Party

The Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party ( ' ), also known simply as Bath Party (), was a political party founded in Syria by Michel Aflaq, Salah al-Din al-Bitar, and associates of Zaki al-Arsuzi. The party espoused Ba'athism, which is an ideology ...

to power, beginning a new era in Syrian history. It was after this coup that Syria turned towards militarization, and with each new internal party coup it increased. Neo-Ba'athism

Neo-Ba'athism is a far-left variant of Ba'athism that became the state ideology of Ba'athist Syria, after Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, Arab Socialist Ba'ath party's sixth national congress in September 1963. As a result of the 1966 Syrian coup ...

(whose supporters came to power in 1966) differed greatly from the standard version of Ba'athism

Ba'athism, also spelled Baathism, is an Arab nationalist ideology which advocates the establishment of a unified Arab state through the rule of a Ba'athist vanguard party operating under a revolutionary socialist framework. The ideology i ...

, including the idea of strong militarization.

In 1970 (after another coup), military General Hafez al-Assad

Hafez al-Assad (6 October 193010 June 2000) was a Syrian politician and military officer who was the president of Syria from 1971 until Death and state funeral of Hafez al-Assad, his death in 2000. He was previously the Prime Minister of Syria ...

came to power. His regime turned out to be the most stable and long-lasting. Assad also conducted an active campaign to militarize Syrian society throughout his rule to resist Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, including alone (starting in the 80s). This policy led to Syria becoming one of the most militarized countries in the world with a large and professional army with high number of soldiers, Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

and tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

fleets.

However, by December 2024, after 13 years of brutal civil war, the Syrian army had become largely degraded and weakened, due to problems such as widespread corruption, lack of fuel

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work (physics), work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chem ...

for armored vehicles, a ruined economy (which made it impossible for the regime

In politics, a regime (also spelled régime) is a system of government that determines access to public office, and the extent of power held by officials. The two broad categories of regimes are democratic and autocratic. A key similarity acros ...

to support its military spending on its own), and low morale among its soldiers. All of this led to the surprisingly rapid collapse of the Bashar Assad's regime as a result of several surprise offensives by the Syrian opposition

Syrians () are the majority inhabitants of Syria, indigenous to the Levant, most of whom have Arabic, especially its Levantine and Mesopotamian dialects, as a mother tongue. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend ...

.

Iraq

Like neighboring Syria, Iraq has been a highly militarized state for decades. From rule ofAbd al-Karim Qasim

Abdul-Karim Qasim Muhammad Bakr al-Fadhli Al-Qaraghuli al-Zubaidi ( ' ; 21 November 1914 – 9 February 1963) was an Iraqi military officer and statesman who served as the Prime Minister and de facto leader of Iraq from 1958 until his ...

until the Ba'athist seizure of power in 1968, the Iraqi government had followed a policy of the militarization

Militarization, or militarisation, is the process by which a society organizes itself for military conflict and violence. It is related to militarism, which is an ideology that reflects the level of militarization of a state. The process of mil ...

of society.

Abdul-Karim Qasim, who seized power in 1958, was an Iraqi nationalist and Qasimist. This brought him into conflict with his neighbors, Kuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, whose territories he claimed (in the Iranian case, only the province of Khuzestan

Khuzestan province () is one of the 31 Provinces of Iran. Located in the southwest of the country, the province borders Iraq and the Persian Gulf, covering an area of . Its capital is the city of Ahvaz. Since 2014, it has been part of Iran's ...

). To protect his ambitions, Qasim needed a competent army, which he was able to build.

After coming to power in 1968, the Ba'athists continued the militarization policies begun by their predecessors. While the period from 1960 to 1980 was peaceful, expenditure on the military trebled: in 1981 it stood at US$4.3 billion and nearly equaled the national incomes of Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

and Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

combined. Per capita military spending in 1981 was 370 percent higher than that for education. During the Iran–Iraq War