Merion C. Cooper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Merian Caldwell Cooper (October 24, 1893 – April 21, 1973) was an American filmmaker and Academy Award winner, as well as a former aviator who served as an officer in the

In October 1917, six months after the

In October 1917, six months after the

During his time as a POW, Cooper wrote an autobiography: ''Things Men Die For''. The manuscript was published by

During his time as a POW, Cooper wrote an autobiography: ''Things Men Die For''. The manuscript was published by

Cooper needed a production studio for the film, but recognized the great cost of the movie, especially during the Great Depression. Cooper helped

Cooper needed a production studio for the film, but recognized the great cost of the movie, especially during the Great Depression. Cooper helped

For his military service in Poland, Cooper was awarded the Silver Cross of the

For his military service in Poland, Cooper was awarded the Silver Cross of the

Cooper's polish-soviet warmini-bio and pictures of Cooper as a teenager

on JaxHistory.Com

Inventory of the Merian C. Cooper papers

at th

Hoover Institution Archives

at Stanford University

Collections relating to Merian C. Cooper

in the

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army S ...

and Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force ( pl, Siły Powietrzne, , Air Forces) is the aerial warfare branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 16,425 mil ...

. In film, he is credited as co-inventor of the Cinerama

Cinerama is a widescreen process that originally projected images simultaneously from three synchronized 35mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, subtending 146° of arc. The trademarked process was marketed by the Cinerama corpora ...

film projection process. Cooper's most famous film was the 1933 movie ''King Kong

King Kong is a fictional giant monster resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. He has been dubbed The Eighth Wonder of the World, a phrase commonly used within the franchise. His first appearance was in the novelizat ...

''. He was awarded an honorary Oscar

The Academy Honorary Award – instituted in 1950 for the 23rd Academy Awards (previously called the Special Award, which was first presented at the 1st Academy Awards in 1929) – is given annually by the Board of Governors of the Academy of Moti ...

for lifetime achievement in 1952 and received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, Calif ...

in 1960. Before entering the movie business, Cooper had a distinguished career as the founder of the Kościuszko Squadron during the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

and was a Soviet prisoner of war for a time. He got his start in with film as part of the Explorers Club

The Explorers Club is an American-based international multidisciplinary professional society with the goal of promoting scientific exploration and field study. The club was founded in New York City in 1904, and has served as a meeting point fo ...

, traveling the world and documenting adventures. He was a member of the board of directors of Pan American Airways, but his love of film always took priority. During his film career, he worked for companies such as Pioneer Pictures

Pioneer Pictures, Inc. was a Hollywood motion picture company, most noted for its early commitment to making color films. Pioneer was initially affiliated with RKO Pictures, whose production facilities in Culver City, California were used by Pion ...

, RKO Pictures

RKO Radio Pictures Inc., commonly known as RKO Pictures or simply RKO, was an American film production and distribution company, one of the "Big Five" film studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. The business was formed after the Keith-Albee-Orph ...

, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 ...

. In 1925 he and Ernest B. Schoedsack

Ernest Beaumont Schoedsack (June 8, 1893 – December 23, 1979) was an American motion picture cinematographer, producer, and director. Schoedsack worked as a cameraman in World War I, where he served in the Signal Corps. At the conclusion of ...

came to Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

and made '' Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life'', a documentary about the Bakhtiari people

The Bakhtiari (also spelled Bakhtiyari; fa, بختیاری) are a Lur tribe from Iran. They speak the Bakhtiari dialect of the Luri language.

Bakhtiaris primarily inhabit Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari and eastern Khuzestan, Lorestan, Bushehr, ...

.

Early life

Merian Caldwell Cooper was born inJacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

, to the lawyer John C. Cooper and the former Mary Caldwell. He was the youngest of three children. At age six, Cooper decided that he wanted to be an explorer after hearing stories from the book ''Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa''. He was educated at The Lawrenceville School

The Lawrenceville School is a coeducational preparatory school for boarding and day students located in the Lawrenceville section of Lawrence Township, in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. Lawrenceville is a member of the Eight Scho ...

in New Jersey and graduated in 1911.

After graduation, Cooper received a prestigious appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy is ...

, but was expelled during his senior year for "hell raising and for championing air power". In 1916, Cooper worked for the ''Minneapolis Daily News'' as a reporter, where he met Delos Lovelace

Delos Wheeler Lovelace (December 2, 1894 – January 17, 1967) was an American novelist who authored the original novelization of the film ''King Kong'' (1933) published in 1932 by Grosset & Dunlap, slightly before the film was released. The sto ...

. In the next few years, he also worked at the ''Des Moines Register-Leader'' and the ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch.''

Early military service

Georgia National Guard

In 1916, Cooper joined the GeorgiaNational Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

N ...

to help chase Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

in Mexico. He was called home in March 1917. He worked for the ''El Paso Herald'' on a 30-day leave of absence. After returning to his service, Cooper was appointed lieutenant; however, he refused the appointment hoping to participate in combat. Instead, he went to the Military Aeronautics School in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,71 ...

to learn to fly. Cooper graduated from the school as the top in his class.

World War I

In October 1917, six months after the

In October 1917, six months after the American entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

, Cooper went to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

with the 201st Squadron. He attended flying school in Issoudun

Issoudun () is a commune in the Indre department, administrative region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is also referred to as ''Issoundun'', which is the ancient name.

Geography Location

Issoudun is a sub-prefecture, located in the east o ...

. While flying with his friend, Cooper hit his head and was knocked out during a 200-foot plunge. After the incident, Cooper suffered from shock and had to relearn how to fly. Cooper requested to go to Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand (, ; ; oc, label= Auvergnat, Clarmont-Ferrand or Clharmou ; la, Augustonemetum) is a city and commune of France, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, with a population of 146,734 (2018). Its metropolitan area (''aire d'attra ...

to be trained as a bomber pilot. He became a pilot with the 20th Aero Squadron

The 20th Aero Squadron was a United States Army Air Service unit that fought on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I.

The squadron was assigned as a Day Bombardment Squadron, performing long-range bombing attacks o ...

(which later became the 1st Day Bombardment Group

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

).

Cooper served as a DH-4 bomber pilot with the United States Army Air Service

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 9 (also known as the ''"Air Service"'', ''"U.S. Air Service"'' and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the ''"Air Service, United States Army"'') was the aerial warf ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. On September 26, 1918, his plane was shot down. The plane caught fire, and Cooper spun the plane to suck the flames out. Cooper survived, although he suffered burns, injured his hands, and was presumed dead. German soldiers saw his plane's incredible landing and took him to a prisoner reserve hospital.

Captain Cooper remained in the Air Service after the war; he helped with Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, holding o ...

's U.S. Food Administration that provided aid to Poland. He later became the chief of the Poland division.

Kościuszko Squadron

From late 1919 until the 1921Treaty of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet War ...

, Cooper was a member of a volunteer American flight squadron, the Kościuszko Squadron, which supported the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history str ...

in the Polish-Soviet War. On July 13, 1920, his plane was shot down and he spent nearly nine months in a Soviet prisoner of war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military priso ...

where the writer Isaac Babel

Isaac Emmanuilovich Babel (russian: Исаак Эммануилович Бабель, p=ˈbabʲɪlʲ; – 27 January 1940) was a Russian writer, journalist, playwright, and literary translator. He is best known as the author of '' Red Cavalry' ...

interviewed him. He escaped just before the war was over and made it to Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

. For his valor he was decorated by Polish commander-in-chief Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

with the highest Polish military decoration, the Virtuti Militari

The War Order of Virtuti Militari (Latin: ''"For Military Virtue"'', pl, Order Wojenny Virtuti Militari) is Poland's highest military decoration for heroism and courage in the face of the enemy at war. It was created in 1792 by Polish King Stan ...

.

During his time as a POW, Cooper wrote an autobiography: ''Things Men Die For''. The manuscript was published by

During his time as a POW, Cooper wrote an autobiography: ''Things Men Die For''. The manuscript was published by G. P. Putnam's Sons

G. P. Putnam's Sons is an American book publisher based in New York City, New York. Since 1996, it has been an imprint of the Penguin Group.

History

The company began as Wiley & Putnam with the 1838 partnership between George Palmer Putnam and ...

in New York (the Knickerbocker Press) in 1927. However, in 1928 Cooper regretted releasing certain details about "Nina" (probably Małgorzata Słomczyńska) with whom he had had relations outside of wedlock. Cooper then asked Dagmar Matson, who had the manuscript, to buy all the copies of the book possible. Matson found almost all 5,000 copies that had been printed. The books were destroyed, while Cooper and Matson each kept a copy.

An interbellum

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

Polish film directed by Leonard Buczkowski, '' Gwiaździsta eskadra'' (The Starry Squadron), was inspired by Cooper's experiences as a Polish Air Force officer. The film was made with the cooperation of the Polish army and was the most expensive Polish film prior to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. After World War II, all copies of the film found in Poland were destroyed by the Soviets.

Career

Cooper and Schoedsack

After returning from overseas in 1921, Cooper got a job working the night shift at ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

.'' He was commissioned to write articles for ''Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

'' magazine. Cooper was able to travel with Ernest Schoedsack

Ernest Beaumont Schoedsack (June 8, 1893 – December 23, 1979) was an American motion picture cinematographer, producer, and director. Schoedsack worked as a cameraman in World War I, where he served in the Signal Corps. At the conclusion of ...

on a sea voyage on the ''Wisdom II''. As part of the journey, he traveled to Abyssinia, or the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historical ...

, where he met their prince regent, Ras Tefari, later known as Emperor Haile Selassie I

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia ('' ...

. The ship left Abyssinia in February 1923. On their way home, the crew narrowly missed being attacked by pirates, and the ship was burned down. His three-part series for ''Asia'' was published in 1923.

After returning home, Cooper researched for the American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows from around the ...

. In 1924, Cooper joined Schoedsack and Marguerite Harrison

Marguerite Elton Harrison (1879–1967) was an American reporter, spy, filmmaker and translator. She was also one of the four founding members of the Society of Woman Geographers.

Biography

Harrison was born Marguerite Elton Baker, one of two da ...

who had embarked on an expedition that would be turned into the film ''Grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in law ...

'' (1925). They returned later the same year. Cooper became a member of the Explorers Club of New York in January 1925 and was asked to give lectures and attend events due to his extensive traveling. ''Grass'' was acquired by Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

. This first film of Cooper and Schoedsack gained the attention of Jesse Lasky

Jesse Louis Lasky (September 13, 1880 – January 13, 1958) was an American pioneer motion picture producer who was a key founder of what was to become Paramount Pictures, and father of screenwriter Jesse L. Lasky Jr.

Early life

Born in to ...

, who commissioned the duo for their second film, '' Chang'' (1927). They also produced the film ''The Four Feathers

''The Four Feathers'' is a 1902 adventure novel by British writer A. E. W. Mason that has inspired many films of the same title. In December 1901, ''Cornhill Magazine'' announced the title as one of two new serial stories to be published in th ...

,'' which was filmed among the fighting tribes of the Sudan. These films combined real footage with staged sequences.

Pan American Airways

Between 1926 and 1927, Cooper discussed with John Hambleton the plans forPan American Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

, which was formed during 1927. Cooper was a member of the board of directors of Pan American Airways. During his tenure at Pan Am, the company established the first regularly scheduled transatlantic service. While he was on the board, Cooper did not devote his full attention to the organization; he took time in 1929 and 1930 to work on the script for ''King Kong

King Kong is a fictional giant monster resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. He has been dubbed The Eighth Wonder of the World, a phrase commonly used within the franchise. His first appearance was in the novelizat ...

.'' By 1931, he was back in Hollywood. He resigned from the board of directors in 1935, following health complications.

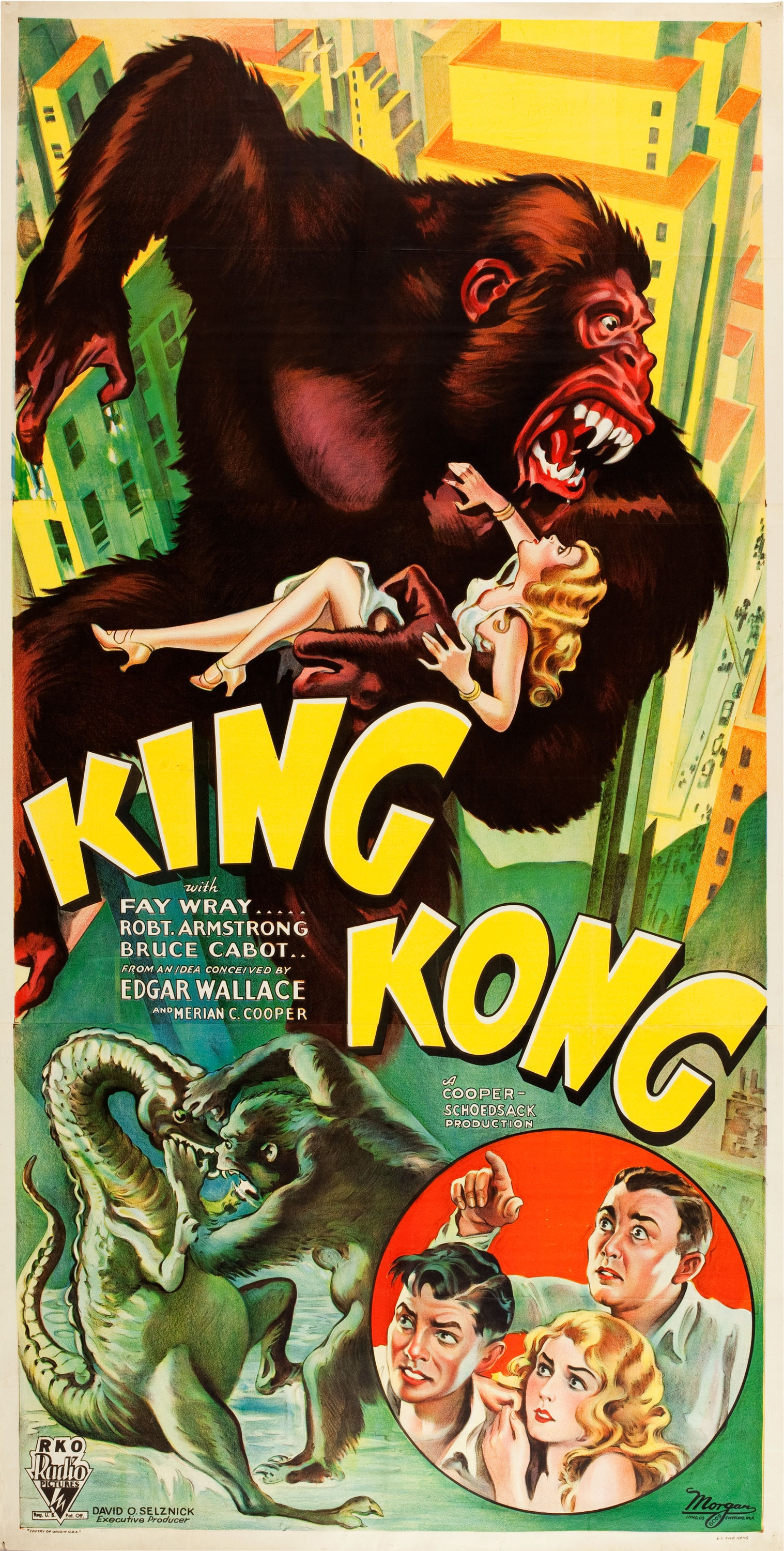

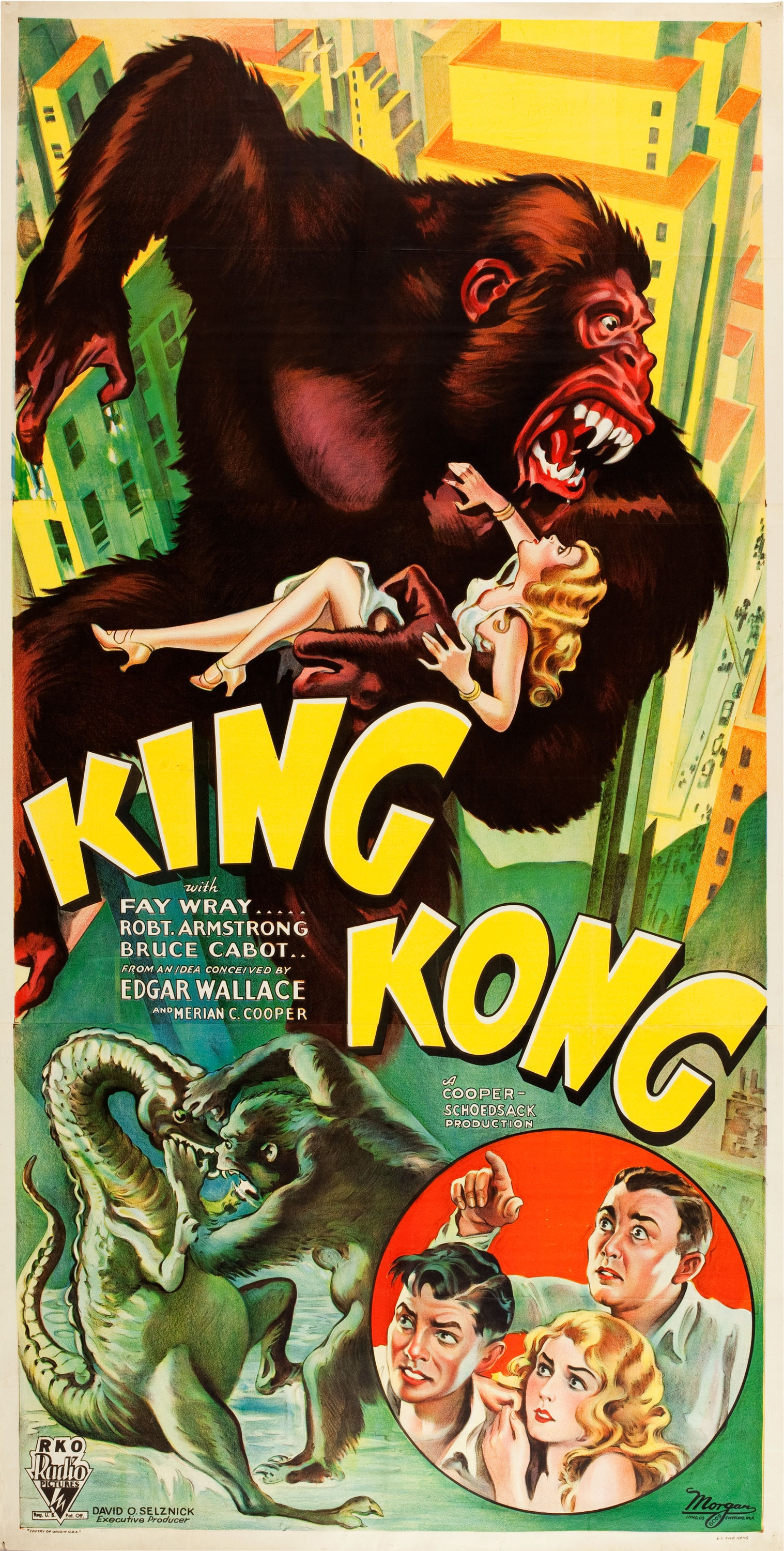

''King Kong''

Cooper said that he thought of ''King Kong'' after he had a dream that a giant gorilla was terrorizing New York City. When he awoke, he recorded the idea and used it for the film. He was going to have a giant gorilla fight aKomodo dragon

The Komodo dragon (''Varanus komodoensis''), also known as the Komodo monitor, is a member of the monitor lizard family Varanidae that is endemic to the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang. It is the largest ext ...

or other animal, but found that the technique of interlacing that he wanted to use would not provide realistic results.

Cooper needed a production studio for the film, but recognized the great cost of the movie, especially during the Great Depression. Cooper helped

Cooper needed a production studio for the film, but recognized the great cost of the movie, especially during the Great Depression. Cooper helped David Selznick

David O. Selznick (May 10, 1902June 22, 1965) was an American film producer, screenwriter and film studio executive who produced '' Gone with the Wind'' (1939) and ''Rebecca'' (1940), both of which earned him an Academy Award for Best Picture.

...

get a job at RKO Pictures

RKO Radio Pictures Inc., commonly known as RKO Pictures or simply RKO, was an American film production and distribution company, one of the "Big Five" film studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. The business was formed after the Keith-Albee-Orph ...

, which was struggling financially. Selznick became the vice president of RKO and asked Cooper to join him in September 1931, although he had only produced three films thus far in his career. Cooper began working as an executive assistant at age thirty-eight. He officially pitched the idea for ''King Kong'' in December 1931. Shortly after, he began to seek actors and build full-scale sets, although the screenplay was not yet complete.

The screenplay was delivered to Cooper in January 1932. Schoedsack contributed to the film, focusing on shooting scenes for the boat sequences and in native villages, leaving Cooper to shoot the jungle scenes. In February 1933, the title for the film was registered for copyright. Throughout filming there were creative battles. Critics at RKO argued that the film should begin with Kong. Cooper believed that a film should begin with a "slow dramatic buildup that would establish everything from characters to mood ..." so that the action of the film could "naturally, relentlessly, roll on out of its own creative movement," and thus chose to not begin the film with a shot of Kong. The iconic scene in which Kong is atop of the Empire State Building

The Empire State Building is a 102-story Art Deco skyscraper in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The building was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and built from 1930 to 1931. Its name is derived from " Empire State", the nickname of the ...

was almost cancelled by Cooper for legal reasons, but was kept in the film because RKO bought the rights to ''The Lost World

The lost world is a subgenre of the fantasy or science fiction genres that involves the discovery of an unknown Earth civilization. It began as a subgenre of the late-Victorian adventure romance and remains popular into the 21st century.

The g ...

''.

Overlapping with the production of ''King Kong'' was the making of ''The Most Dangerous Game

"The Most Dangerous Game", also published as "The Hounds of Zaroff", is a short story by Richard Connell, first published in ''Collier's'' on January 19, 1924, with illustrations by Wilmot Emerton Heitland. The story features a big-game hunter ...

'', which began in May 1932. Cooper once again worked with Schoedsack to produce the film.

In the 1933 version of ''King Kong'', Cooper and co-director Ernest B. Schoedsack

Ernest Beaumont Schoedsack (June 8, 1893 – December 23, 1979) was an American motion picture cinematographer, producer, and director. Schoedsack worked as a cameraman in World War I, where he served in the Signal Corps. At the conclusion of ...

appear at the end, piloting the plane that finally finishes off Kong. Cooper had reportedly said, "We should kill the sonofabitch ourselves." Cooper personally cut a scene in ''King Kong'' in which four sailors are shaken off a rope bridge by Kong, fall into a ravine, and are eaten alive by giant spiders. According to Hollywood folklore, the decision was made after previews in January 1933, during which audience members either fled the theater in terror or talked about the ghastly scene throughout the remainder of the movie. However, more objective sources maintain that the scene merely slowed the film's pace. Legend has it that Cooper kept a print of the cut footage as a memento, although it has never been found. In 1963, Cooper argued unsuccessfully that he should own the rights to ''King Kong''; later in 1976, judges ruled that Cooper's estate owned the rights to King Kong outside the movie and its sequel. Selznick left RKO before the release of ''King Kong'', and Cooper served as production chief from 1933-34 with Pan Berman as his executive assistant.

In the 2005 remake of ''King Kong

King Kong is a fictional giant monster resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. He has been dubbed The Eighth Wonder of the World, a phrase commonly used within the franchise. His first appearance was in the novelizat ...

'', upon learning that Fay Wray

Vina Fay Wray (September 15, 1907 – August 8, 2004) was a Canadian/American actress best known for starring as Ann Darrow in the 1933 film ''King Kong''. Through an acting career that spanned nearly six decades, Wray attained international r ...

was not available because she was making a film at RKO, Carl Denham

Carl Denham is a fictional character in the films ''King Kong'' and ''The Son of Kong'' (both released in 1933), as well as in the 2005 remake of ''King Kong'', and a 2004 illustrated novel titled ''Kong: King of Skull Island''. The role was p ...

(Jack Black

Thomas Jacob Black (born August 28, 1969) is an American actor, comedian, and musician. He is known for his acting roles in the films '' High Fidelity'' (2000), '' Shallow Hal'' (2001), '' Orange County'' (2002), '' School of Rock'' (2003), ' ...

) replies, "Cooper, huh? I might have known."

Pioneer Pictures, Selznick International Pictures, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Cooper helped the Whitney cousins formPioneer Pictures

Pioneer Pictures, Inc. was a Hollywood motion picture company, most noted for its early commitment to making color films. Pioneer was initially affiliated with RKO Pictures, whose production facilities in Culver City, California were used by Pion ...

in 1933, while he was still working for RKO. He was named vice president in charge of production for Pioneer Pictures in 1934. He would use Pioneer Pictures to test his technicolor innovations. The company contracted with RKO in order to fulfill Cooper's obligations to the company, including ''She

She most commonly refers to:

*She (pronoun), the third person singular, feminine, nominative case pronoun in modern English.

She or S.H.E. may also refer to:

Literature and films

*'' She: A History of Adventure'', an 1887 novel by H. Rider Hagga ...

'' and ''The Last Days of Pompeii

''The Last Days of Pompeii'' is a novel written by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1834. The novel was inspired by the painting ''The Last Day of Pompeii'' by the Russian painter Karl Briullov, which Bulwer-Lytton had seen in Milan. It culminates in ...

''. Cooper later referred to ''She'' as the "worst picture I ever made."

After these disappointments, Pioneer Pictures released a short film in three-strip technicolor

Technicolor is a series of color motion picture processes, the first version dating back to 1916, and followed by improved versions over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black and white films running through a special ...

called ''La Cucaracha'' which was well received. The film won an Academy Award in 1934. Pioneer released the first full-length technicolor film, ''Becky Sharp

Rebecca "Becky" Sharp, later describing herself as Rebecca, Lady Crawley, is the main protagonist of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847–48 novel '' Vanity Fair''. She is presented as a cynical social climber who uses her charms to fascinate ...

'' in 1935. Cooper helped to advocate and pave the way for the ground-breaking technology of technicolor, as well as the widescreen process called Cinerama

Cinerama is a widescreen process that originally projected images simultaneously from three synchronized 35mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, subtending 146° of arc. The trademarked process was marketed by the Cinerama corpora ...

.

Selznick formed Selznick International Pictures

Selznick International Pictures was a Hollywood motion picture studio created by David O. Selznick in 1935, and dissolved in 1943. In its short existence the independent studio produced two films that received the Academy Award for Best Picture— ...

in 1935, and Pioneer Pictures merged with it in June 1936. Cooper became the vice president of Selznick International Pictures that same year. Cooper did not stay long; he resigned in 1937 due to disagreements over the film ''Stagecoach

A stagecoach is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by four horses although some versions are draw ...

''.

After resigning from Selznick International, Cooper went to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 ...

(MGM) in June 1937. Cooper's most successful film at MGM was ''War Eagles''. The film was postponed during World War II, and Cooper returned to the Air Force. The film was abandoned, however, and never finished.

World War II

Cooper re-enlisted and was commissioned acolonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

in the U.S. Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

. He served with Col. Robert L. Scott

Robert L. Scott (April 19, 1928 – July 26, 2018) was an American scholar influential in the study of rhetorical theory, criticism of public address, debate, and communication research and practice. He was professor emeritus in the Communicatio ...

in India. He worked as logistics liaison for the Doolittle Raid

The Doolittle Raid, also known as the Tokyo Raid, was an air raid on 18 April 1942 by the United States on the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Honshu during World War II. It was the first American air operation to strike the Japan ...

. Thereafter, Cooper and Scott worked with Col. Caleb V. Haynes

Caleb Vance Haynes (March 15, 1895 – April 5, 1966) was a United States Air Force (USAF) major general. The grandson of Chang Bunker, a famous Siamese Twin, he served in the Air Force as an organizer, able to create air units from scratch. H ...

at Dinjan

Dinjan (or Dinjoy gaon) is a small township in Dibrugarh district of Assam, India. It is located in the tea growing area of Assam. The closest town to it is Tinsukia. During World War II, nearby Dinjan Airfield was used by transport aircraft wh ...

Airfield. They all were involved in establishing the Assam-Burma-China Ferrying Command. This marked the beginnings of The Hump

The Hump was the name given by Allied pilots in the Second World War to the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains over which they flew military transport aircraft from India to China to resupply the Chinese war effort of Chiang Kai-shek and ...

Airlift.

Colonel Cooper later served in China as chief of staff for General Claire Chennault

Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958) was an American military aviator best known for his leadership of the " Flying Tigers" and the Chinese Air Force in World War II.

Chennault was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fig ...

of the China Air Task Force

The China Air Task Force (CATF) was a combat organization of the United States Army Air Forces created in July 1942 under the command of Brig. Gen. Claire Chennault, after the Flying Tigers of the 1st American Volunteer Group of the Chinese Air For ...

, which was the precursor of the Fourteenth Air Force

The Fourteenth Air Force (14 AF; Air Forces Strategic) was a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Space Command (AFSPC). It was headquartered at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

The command was responsible for the organizati ...

. On 25 October 1942 a CATF raid consisting of 12 B-25s and 7 P-40s, led by Colonel Cooper, successfully bombed the Kowloon Docks at Hong Kong.

He served then from 1943 to 1945 in the Southwest Pacific as chief of staff for the Fifth Air Force

The Fifth Air Force (5 AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Yokota Air Base, Japan. It is the U.S. Air Force's oldest continuously serving Numbered Air Force. The organi ...

's Bomber Command. At the end of the war, he was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

. For his contributions, he was also aboard the USS ''Missouri'' to witness Japan's surrender.

Argosy Pictures and Cinerama

Cooper and his friend and frequent collaborator, noted directorJohn Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), known professionally as John Ford, was an American film director and naval officer. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of his generation. He ...

, formed Argosy Productions in 1946 and produced such notable films such as ''Wagon Master

''Wagon Master'' is a 1950 American Western film produced and directed by John Ford and starring Ben Johnson, Harry Carey Jr., Joanne Dru, and Ward Bond. The screenplay concerns a Mormon pioneer wagon train to the San Juan River in Utah. The ...

'' (1950), Ford's '' Fort Apache'' (1948), and ''She Wore a Yellow Ribbon

''She Wore a Yellow Ribbon'' is a 1949 American Technicolor Western film directed by John Ford and starring John Wayne. It is the second film in Ford's "Cavalry Trilogy", along with '' Fort Apache'' (1948) and ''Rio Grande'' (1950). With a bud ...

.'' Cooper's films at Argosy reflected his patriotism and his vision of the United States.

Argosy negotiated a contract with RKO in 1946 to make four pictures. Cooper was able to make ''Grass'' a complete picture. Argosy also produced '' Mighty Joe Young'', which recruited Schoedsack as director. Cooper visited the set of the film every day to check on progress.

Cooper left Argosy Pictures to pursue the process of Cinerama

Cinerama is a widescreen process that originally projected images simultaneously from three synchronized 35mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, subtending 146° of arc. The trademarked process was marketed by the Cinerama corpora ...

. He became the vice president of Cinerama Productions

Cinerama Releasing Corporation (CRC) was a motion picture company established in 1967 that originally released films produced by its namesake parent company that was considered an "instant major".Page 10.

History

In 1963, the owner of the Paci ...

in the 1950s and was also elected a board member. After failing to convince other board members to finance skilled technicians, Cooper left Cinerama with Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney

Cornelius "Sonny" Vanderbilt Whitney (February 20, 1899 – December 13, 1992) was an American businessman, film producer, government official, writer and philanthropist. He was also a polo player and the owner of a significant stable of Thorough ...

to form C.V. Whitney Productions. Cooper continued to outline movies to be shot in Cinerama, but C.V. Whitney Productions only produced a few films. Cooper was the executive producer for ''The Searchers

''The Searchers'' is a 1956 American Technicolor VistaVision epic Western film directed by John Ford and written by Frank S. Nugent, based on the 1954 novel by Alan Le May. It is set during the Texas-Native American wars, and stars John Way ...

'' (1956), again directed by Ford.

Awards

Order of Virtuti Militari

The War Order of Virtuti Militari (Latin: ''"For Military Virtue"'', pl, Order Wojenny Virtuti Militari) is Poland's highest military decoration for heroism and courage in the face of the enemy at war. It was created in 1792 by Polish King Stan ...

(presented by Piłsudski), and Poland's Cross of Valour.

In 1927 Cooper was one of 19 prominent Americans who were given the title of "Honorary Scouts" by the Boy Scouts of America

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA, colloquially the Boy Scouts) is one of the largest scouting organizations and one of the largest List of youth organizations, youth organizations in the United States, with about 1.2 million youth partici ...

for "... achievements in outdoor activity, exploration and worthwhile adventure ... of such an exceptional character as to capture the imagination of boys". The other honorees were Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews (January 26, 1884 – March 11, 1960) was an American explorer, adventurer and naturalist who became the director of the American Museum of Natural History. He led a series of expeditions through the politically disturbed ...

, Robert Bartlett, Frederick Russell Burnham

Frederick Russell Burnham DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to the British Army in colonial Africa, and for teac ...

, Richard E. Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest honor for valor given by the United States, and was a pioneering American aviator, p ...

, George Kruck Cherrie

George Kruck Cherrie (August 22, 1865 – January 20, 1948) was an American naturalist and explorer. He collected numerous specimens on nearly forty expeditions that he joined for museums and several species have been named after him.

Early lif ...

, James L. Clark James Lippitt Clark (18 November 1883 in Providence, Rhode Island – 1969) was a distinguished American explorer, sculptor and scientist.

Following his studies at the Rhode Island School of Design and his training at the Gorham Silver Company ...

, Lincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth (May 12, 1880 – May 26, 1951) was a polar explorer from the United States and a major benefactor of the American Museum of Natural History.

Biography

Lincoln Ellsworth was born on May 12, 1880, to James Ellsworth and Eva ...

, Louis Agassiz Fuertes

Louis Agassiz Fuertes (February 7, 1874 Ithaca, New York – August 22, 1927 Unadilla, New York) was an American ornithologist, illustrator and artist who set the rigorous and current-day standards for ornithological art and naturalist depictio ...

, George Bird Grinnell

George Bird Grinnell (September 20, 1849 – April 11, 1938) was an American anthropologist, historian, naturalist, and writer. Grinnell was born in Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from Yale University with a B.A. in 1870 and a Ph.D. in 1880 ...

, Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

, Donald Baxter MacMillan

Donald Baxter MacMillan (November 10, 1874 – September 7, 1970) was an American explorer, sailor, researcher and lecturer who made over 30 expeditions to the Arctic during his 46-year career.

He pioneered the use of radios, airplanes, ...

, Clifford H. Pope

Clifford Hillhouse Pope (April 11, 1899 – June 3, 1974) was a noted American herpetologist. He was the son of Mark Cooper Pope and Harriett Alexander (Hull) Pope, and grew up in Washington, Georgia. While in college in the summers of 1919 and ...

, George Palmer Putnam

George Palmer Putnam (February 7, 1814 – December 20, 1872) was an American publisher and author. He founded the firm G. P. Putnam's Sons and '' Putnam's Magazine''. He was an advocate of international copyright reform, secretary for many yea ...

, Kermit Roosevelt

Kermit Roosevelt MC (October 10, 1889 – June 4, 1943) was an American businessman, soldier, explorer, and writer. A son of Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States, Kermit graduated from Harvard College, served in both Wor ...

, Carl Rungius

Carl Clemens Moritz Rungius (August 18, 1869 – October 21, 1959) was a leading American wildlife artist. He was born in Germany though he immigrated to the United States and he spent his career painting in the western United States and ...

, Stewart Edward White

Stewart Edward White (12 March 1873 – September 18, 1946) was an American writer, novelist, and spiritualist. He was a brother of noted mural painter Gilbert White.

Personal life

White was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the son of Mary E. ...

, and Orville Wright.

In 1949 '' Mighty Joe Young'' won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, which was presented to Willis O'Brien, the man responsible for the film's special effects.

Cooper was awarded an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement in 1952. His film ''The Quiet Man

''The Quiet Man'' is a 1952 American romantic comedy-drama film directed by John Ford. It stars John Wayne, Maureen O'Hara, Barry Fitzgerald, Ward Bond and Victor McLaglen. The screenplay by Frank S. Nugent was based on a 1933 ''Saturday Eveni ...

'' was nominated for Best Picture that year, but lost to Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil Blount DeMille (; August 12, 1881January 21, 1959) was an American film director, producer and actor. Between 1914 and 1958, he made 70 features, both silent and sound films. He is acknowledged as a founding father of the American cin ...

's '' The Greatest Show on Earth''. Cooper has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, Calif ...

, though his first name is misspelled "Meriam".

Personal life

Cooper was the father of Polish translator and writer Maciej Słomczyński. He married film actress Dorothy Jordan on May 27, 1933. They kept their marriage a secret from Hollywood for a month before it was reported by journalists. He suffered a heart attack later that year. In the 1950s, he supportedJoseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

in his crusade to root out Communists in Hollywood and Washington, D.C.

Cooper supported Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the United States Republican Party, Republ ...

in the 1964 United States presidential election.

Cooper founded Advanced Projects in his later life and served as the chairman of the board. He wanted to explore new technologies like 3-D color television productions. Cooper died of cancer on April 21, 1973, in San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

. His ashes were scattered at sea with full military honors.

Filmography

References

Further reading

* * * ''I'm King Kong!—The Exploits of Merian C. Cooper'' (2005),TCM

TCM may refer to:

Arts and music

Film

* ''The Texas Chainsaw Massacre'' (franchise), a horror film franchise

** '' The Texas Chain Saw Massacre'', the original 1974 film

** ''The Texas Chainsaw Massacre'' (2003 film), the 2003 remake

Games

* ...

documentary on Cooper, directed by Kevin Brownlow

Kevin Brownlow (born Robert Kevin Brownlow; 2 June 1938) is a British film historian, television documentary-maker, filmmaker, author, and film editor. He is best known for his work documenting the history of the silent era, having become inte ...

.

External links

*Cooper's polish-soviet war

on JaxHistory.Com

Archival materials

Inventory of the Merian C. Cooper papers

at th

Hoover Institution Archives

at Stanford University

Collections relating to Merian C. Cooper

in the

L. Tom Perry Special Collections

The L. Tom Perry Special Collections is the special collections department of Brigham Young University (BYU)'s Harold B. Lee Library in Provo, Utah. Founded in 1957 with 1,000 books and 50 manuscript collections, as of 2016 the Library's speci ...

, Harold B. Lee Library

The Harold B. Lee Library (HBLL) is the main academic library of Brigham Young University (BYU) located in Provo, Utah. The library started as a small collection of books in the president's office in 1876 before moving in 1891. The Heber J. Gra ...

Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU, sometimes referred to colloquially as The Y) is a private research university in Provo, Utah. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cooper, Merian C.

1893 births

1973 deaths

Military personnel from Florida

20th-century American male actors

Academy Honorary Award recipients

American anti-communists

American male film actors

American people of English descent

American prisoners of war in World War I

Aviators from Florida

Bomber pilots

California Republicans

Deaths from cancer in California

Film directors from Florida

Film producers from Florida

Florida Republicans

Harold B. Lee Library-related film articles

Lawrenceville School alumni

People from Jacksonville, Florida

Polish people of the Polish–Soviet War

Recipients of the Cross of Valour (Poland)

Recipients of the Silver Cross of the Virtuti Militari

Shot-down aviators

United States Army Air Forces bomber pilots of World War II

United States Army Air Forces officers

United States Army Air Service pilots of World War I

United States Army colonels

United States Army personnel of World War I

World War I prisoners of war held by Germany