Mensur on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Academic fencing () or is the traditional kind of

Modern academic fencing, the , is neither a

Modern academic fencing, the , is neither a

Starting in Spain at the end of the 15th century, the dueling sword (

Starting in Spain at the end of the 15th century, the dueling sword ( The

The

American traveller

American traveller

fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

practiced by some student corporations () in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

, Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, and, to a minor extent, in Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. It is a traditional, strictly regulated sabre fight between two male members of different fraternities with sharp weapons. The German technical term (from Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

meaning 'dimension') in the 16th century referred to the specified distance between each of the fencers.

Technique

duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapons.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and later the small sword), but beginning in ...

nor a sport

Sport is a physical activity or game, often Competition, competitive and organization, organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators. The numbe ...

. It is a traditional way of training and educating character and personality; thus, in a bout, there is neither winner nor loser. In contrast to sports fencing, the participants stand their ground at a fixed distance. At the beginning of the tradition, duelers wore only their normal clothing (as duels sometimes would arise spontaneously) or light-cloth armor on the arm, torso, and throat. In recent years, fencers are protected by mail

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letter (message), letters, and parcel (package), parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid ...

or padding for the body, fencing arm, fencing hand ( gauntlet) and the throat, completed by steel goggles with a nose guard. In Austria and Switzerland, a nose guard is uncommon. Opponents fence at arm's length and stand more or less in one place, while attempting to hit the unprotected areas of their opponent's face and head. Flinching or dodging is not allowed, the goal being less to avoid injury than to endure it stoically. Two physicians are present (one for each opponent) to attend to injuries and stop the fight if necessary.

The participants, or , use specially developed swords. The so-called (or simply ) exists in two versions. The most common weapon is the with a basket-type guard

Guard or guards may refer to:

Professional occupations

* Bodyguard, who protects an individual from personal assault

* Crossing guard, who stops traffic so pedestrians can cross the street

* Lifeguard, who rescues people from drowning

* Prison gu ...

. Some universities use the so-called (), which is equipped with a bell-shaped guard. These universities are Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin and Neubrandenburg. In 2021 it surpa ...

, Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, Tharandt (in the Forestry College, which is now part of Technische Universität Dresden), Halle on the Saale, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder

Frankfurt (Oder), also known as Frankfurt an der Oder (, ; Marchian dialects, Central Marchian: ''Frankfort an de Oder,'' ) is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Brandenburg after Potsdam, Cottbus and Brandenburg an der Havel. With a ...

, and Freiberg

Freiberg () is a university and former mining town in Saxony, Germany, with around 41,000 inhabitants. The city lies in the foreland of the Ore Mountains, in the Saxon urbanization axis, which runs along the northern edge of the Elster and ...

. In Jena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

, both and are used. from some western cities use because their tradition had its origin in one of the eastern universities but moved to West Germany after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

The scar resulting from a hit is called a "smite" (), and was seen as a badge of honour, especially in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th. Nowadays the presence of scars usually indicates a mistake and therefore are no longer considered especially dignified. Today, it is not easy for an outsider to identify Mensur scars due to better medical treatment. Also, the number of mandatory Mensuren was reduced in the second half of the 20th century. Most Mensur scars are located on the left temple of the forehead. Scars on the cheek and chin are rather uncommon today and sometimes due to accidents.

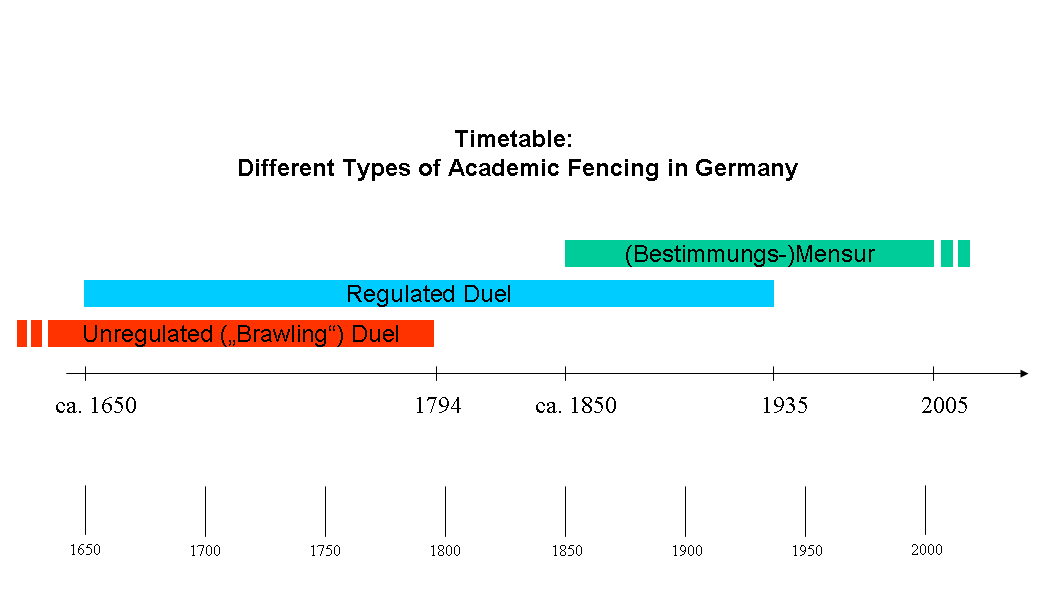

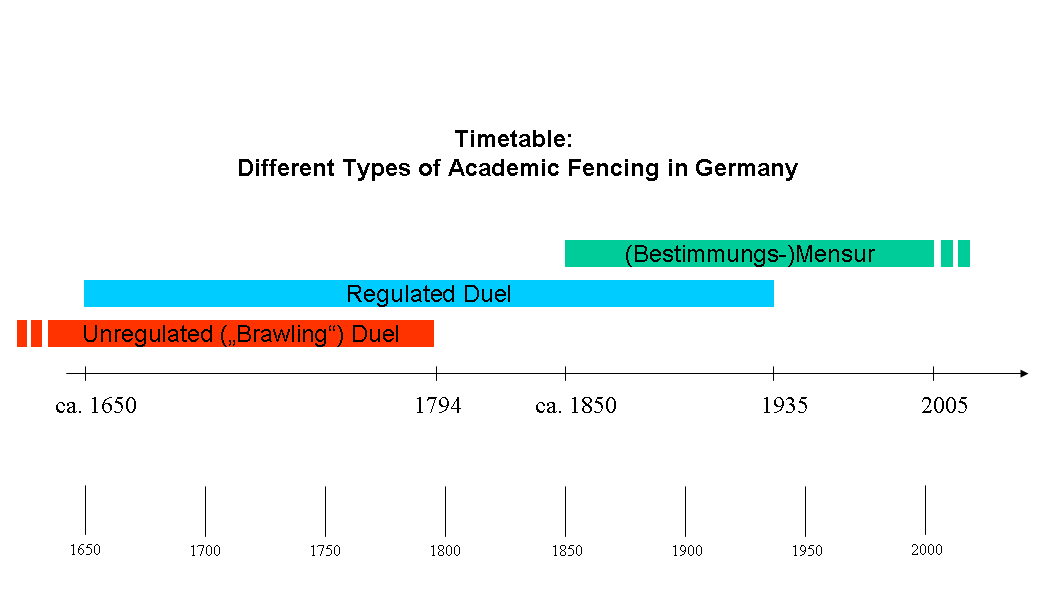

History

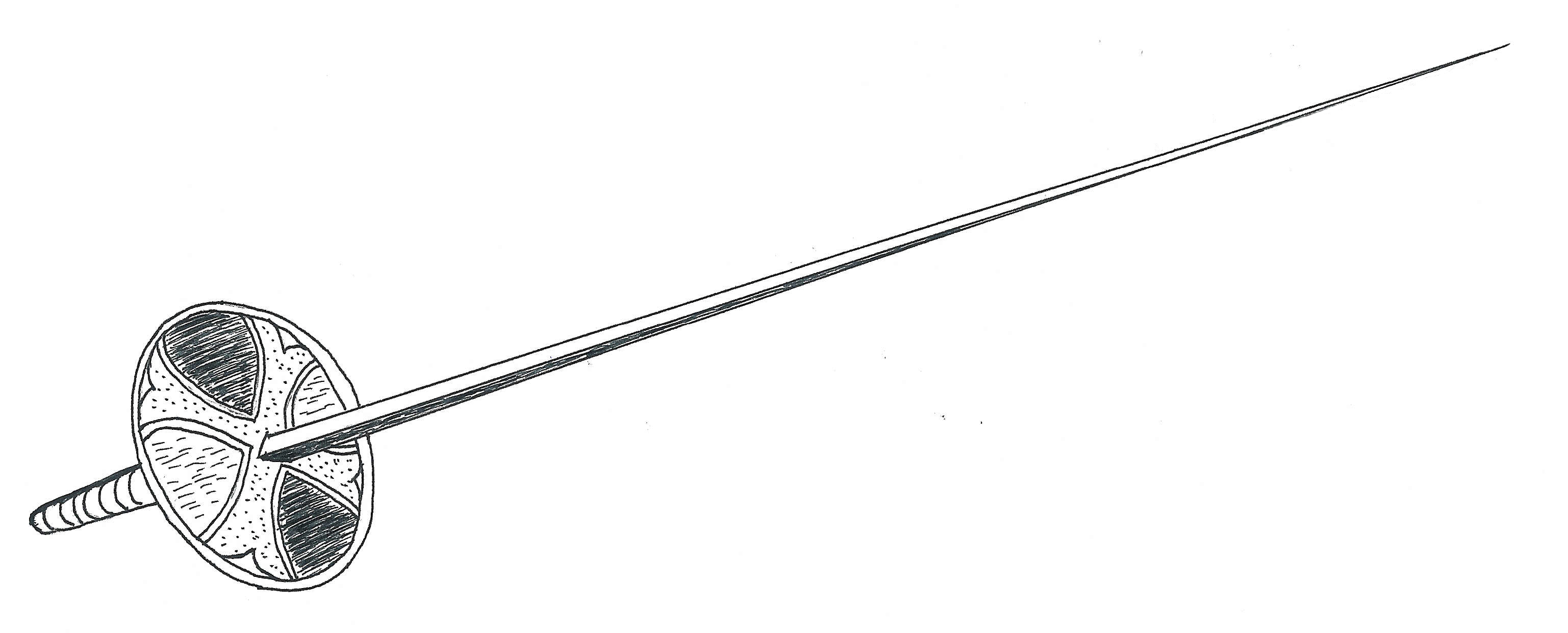

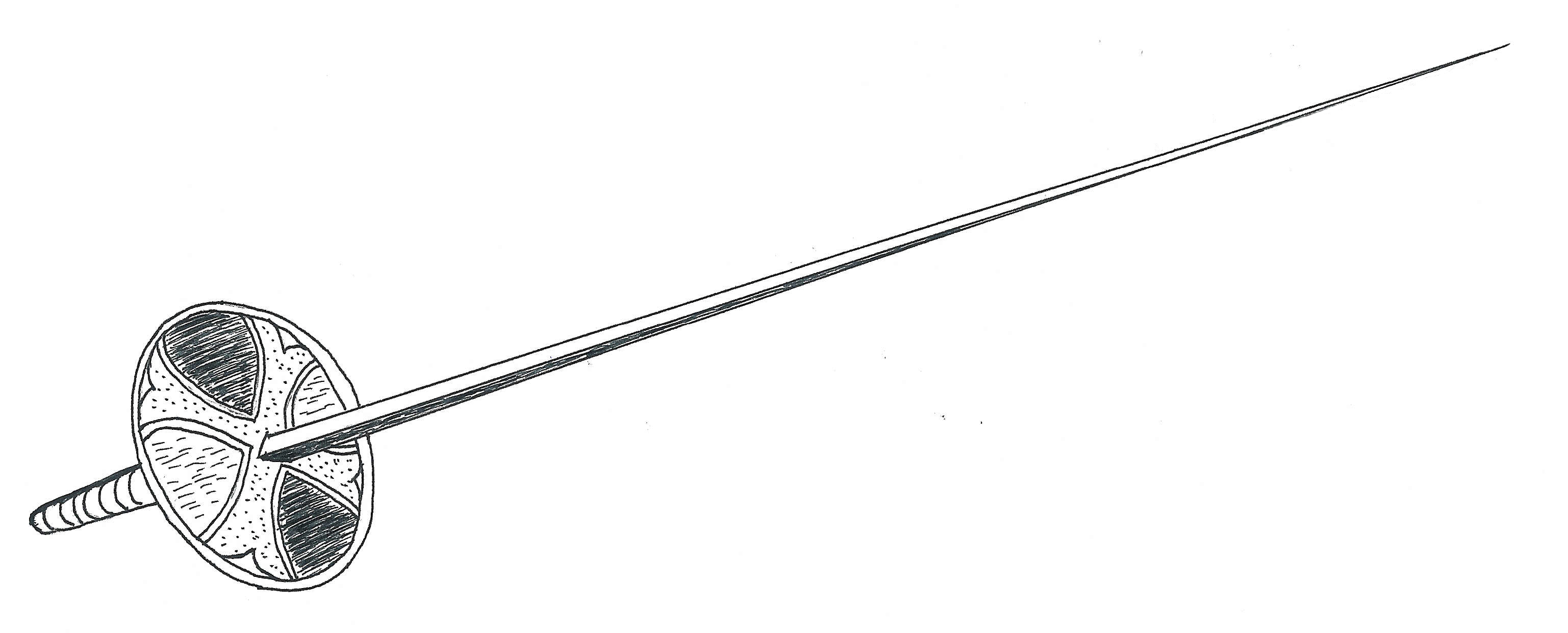

Starting in Spain at the end of the 15th century, the dueling sword (

Starting in Spain at the end of the 15th century, the dueling sword (rapier

A rapier () is a type of sword originally used in Spain (known as ' -) and Italy (known as '' spada da lato a striscia''). The name designates a sword with a straight, slender and sharply pointed two-edged long blade wielded in one hand. It wa ...

) became a regular part of the attire of noblemen throughout Europe. In the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, this became usual among students, as well. Brawling and fighting were regular occupations of students in the German-speaking areas during the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

. In line with developments in the aristocracy and the military, regulated duels were introduced to the academic environment, as well. The basis of this was the conviction that being a student meant being something different from the rest of the population. Students wore special clothes, developed special kinds of festivities, sang student songs, and fought duels, sometimes spontaneously (so-called , French "meeting" or "combat"), sometimes according to strict regulations called (French "how"). The weapons used were the same as those employed in civilian dueling

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapons.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and later the small sword), but beginning in t ...

, being at first the rapier

A rapier () is a type of sword originally used in Spain (known as ' -) and Italy (known as '' spada da lato a striscia''). The name designates a sword with a straight, slender and sharply pointed two-edged long blade wielded in one hand. It wa ...

and later the smallsword (court sword, dress sword, , ), which was seen as part of the dress and always at hand as a side arm.

Student life was quite unsafe in these years, especially in the 16th and 17th centuries during the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

wars and the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

(1618–1648), when a major part of the German population was killed. Public life was brutal and students killing each other in the street was not uncommon.

A major step towards civilization was the introduction of the "regulated" duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapons.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and later the small sword), but beginning in ...

, of which the first recordings exist from the 17th century. The fight was not decided on the spot, but the time and location were appointed and negotiations were done by officials. A so-called did the arrangements and a "second" represented the interests of the fighter during the duel and could even give physical protection from illegal actions. A kind of referee was present to make decisions, and eventually, the practice of having an attending doctor became normal so as to give medical help in case of an injury.

At the end of the 18th century (after the French Revolution), wearing weapons in everyday life fell out of fashion and was more and more forbidden, even for students. This certainly reduced the number of spontaneous duels dramatically. The regulated duel remained in use, though still forbidden.

The

The foil

Foil may refer to:

Materials

* Foil (metal), a quite thin sheet of metal, usually manufactured with a rolling mill machine

* Metal leaf, a very thin sheet of decorative metal

* Aluminium foil, a type of wrapping for food

* Tin foil, metal foil ma ...

was invented in France as a training weapon in the middle of the 18th century to practice fast and elegant thrust fencing. Fencers blunted the point by wrapping a foil around the blade or fastening a knob on the point ("blossom", ). In addition to practising, some fencers took away the protection and used the sharp foil for duels. German students took up that practice and developed the ("Parisian") thrusting small sword for the ("thrusting mensur"). After the dress sword was abolished, the became the only weapon for academic thrust fencing in Germany.

Since fencing on thrust with a sharp point is quite dangerous, many students died from their lungs being pierced (), which made breathing difficult or impossible. However, the counter-movement had already started in Göttingen in the 1760s. Here the was invented, the predecessor of the modern , a new weapon for cut fencing. In the following years, the was invented in east German universities for cut fencing as well.

Thrust fencing (using ) and cut fencing (using or ) existed in parallel in Germany during the first decades of the 19th century—with local preferences. Thrust fencing was especially popular in Jena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

, Erlangen

Erlangen (; , ) is a Middle Franconian city in Bavaria, Germany. It is the seat of the administrative district Erlangen-Höchstadt (former administrative district Erlangen), and with 119,810 inhabitants (as of 30 September 2024), it is the smalle ...

, Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is, after Nuremberg and Fürth, the Franconia#Towns and cities, third-largest city in Franconia located in the north of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Lower Franconia. It sp ...

, and Ingolstadt

Ingolstadt (; Austro-Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian: ) is an Independent city#Germany, independent city on the Danube, in Upper Bavaria, with 142,308 inhabitants (as of 31 December 2023). Around half a million people live in the metropolitan ...

/Landshut

Landshut (; ) is a town in Bavaria, Germany, on the banks of the Isar, River Isar. Landshut is the capital of Lower Bavaria, one of the seven administrative regions of the Free state (government), Free State of Bavaria, and the seat of the surrou ...

, two towns where the predecessors of Munich University were located. The last thrust is recorded to have taken place in Würzburg in 1860.

Until the first half of the 19th century, all types of academic fencing can be seen as duels, since all fencing with sharp weapons was about honour. No combat with sharp blades took place without a formal insult. Compared to pistol duels, these events were relatively harmless. The fight regularly ended when a contestant received a wound at least one inch long that produced at least one drop of blood. It was not uncommon for students to have fought approximately 10 to 30 duels of that kind during their university years. The German student Fritz Bacmeister is the 19th-century record holder, due to his estimated 100 mensur bouts fought in Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

, Jena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

, and Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is, after Nuremberg and Fürth, the Franconia#Towns and cities, third-largest city in Franconia located in the north of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Lower Franconia. It sp ...

between 1860 and 1866.

In the 20th and 21st century it was Alexander Kliesch (Landsmannschaft Brandenburg Berlin) with 70.

For duels with nonstudents, e.g., military officers, the "academic sabre" became usual, apparently derived from the military sabre

A sabre or saber ( ) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the Early Modern warfare, early modern and Napoleonic period, Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such a ...

. It was a heavy weapon with a curved blade and a hilt similar to the .

During the first half of the 19th century and some of the 18th century, students believed the character of a person could easily be judged by watching him fight with sharp blades under strict regulations. Academic fencing was more and more seen as a kind of personality training by showing countenance and fairness even in dangerous situations. Student corporations demanded their members fight at least one duel with sharp blades during their university time. The problem was that some peaceful students had nobody to offend them. The solution was a kind of formal insult that did not actually infringe honour, but was just seen as a challenge for fencing. The standard wording was (German for "stupid boy.")

In the long term, this solution was unsatisfying. Around 1850, the (German means "ascertain", "define" or "determine") was developed and introduced throughout Germany. This meant the opponents of a were determined by the fencing official of their corporations. These officials were regularly vice-chairmen () and responsible for arranging bouts in cooperation with their colleagues from other corporations. Their objective was to find opponents of equal physical and fencing capabilities to make the event challenging for both participants. That is the way it is still done today and is the concept of the in the modern sense of the word.

Before the Communist revolution

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism. Depending on the type of government, the term socialism can be used to indicate an intermediate stage between ...

in Russia and before World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, academic fencing was known in most countries of Eastern Europe, as well.

Modern mensur

By the end of the 19th century, the dueling form evolved into the modern Mensur. In 1884, the British '' Saturday Review'' described the dueling as follows: During the times of theThird Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

, the national socialist leadership initially legalized the practice in 1935, but would again forbid it 1937 as part of the broader crackdown on independent student organizations, which included the . As Nazi pressure increased and fraternities were forced to officially suspend their activities, so-called comradeships were founded. These provided means for practicing and organising the among former fraternities while remaining undetected to the Nazi secret police. One such example was the SC-Comradeship ''Hermann Löns

Hermann Löns (29 August 1866 – 26 September 1914) was a German journalist and writer. He is most famous as "The Poet of the Heath" for his novels and poems celebrating the people and landscape of the North German moors, particularly the L ...

'' initiated by members of the Corps Hubertia Freiburg and other fraternities in Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

, Germany. There, fencing Mensur "duels" continued and even intensified from 1941 on, with over 100 of such duels happening during World War II in Freiburg alone. Following the war, most of the formerly suspended fraternities were reactivated and resumed the traditions of Mensur fencing if they had not continued throughout the time of Nazi occupation.

Today, the Mensur is practiced by about 400 traditional fraternities in Germany, several of the , , , , and . , as the is known in Poland, is still practiced, although its popularity has declined since the end of World War II. It is also still known in a few other European countries, though there, protective equipment use is extensive and dueling scars are almost unheard of.

In popular culture

Literature

American traveller

American traveller Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

devoted several chapters of ''A Tramp Abroad

''A Tramp Abroad'' is a work of travel literature, including a mixture of autobiography and fictional events, by American author Mark Twain, published in 1880. The book details a journey by the author, with his friend Harris (a character created ...

'' (1880) to Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

students' fencing.

In ''Three Men on the Bummel

''Three Men on the Bummel'' (also known as ''Three Men on Wheels'') is a humorous novel by Jerome K. Jerome. It was published in 1900, eleven years after his most famous work, ''Three Men in a Boat''.

The sequel brings back the three companio ...

'' (1900), Jerome K. Jerome devoted a chapter to German student life, and describes the "German " in detail. While much of the book has a tone of admiration for the German people, he expressed extreme disapproval for this tradition.

In George MacDonald Fraser

George MacDonald Fraser (2 April 1925 – 2 January 2008) was a Scottish author and screenwriter. He is best known for a series of works that featured the character Harry Paget Flashman, Flashman. Over the course of his career he wrote eleven n ...

's '' Royal Flash'' (1970), the protagonist Harry Flashman

Sir Harry Paget Flashman is a fictional character created by Thomas Hughes (1822–1896) in the semi-autobiographical '' Tom Brown's School Days'' (1857) and later developed by George MacDonald Fraser (1925–2008). Harry Flashman appears in a ...

is scarred with a as part of his disguise as a Danish prince.

is featured in Heinrich Mann

Luiz Heinrich Mann (; March 27, 1871 – March 11, 1950), best known as simply Heinrich Mann, was a German writer known for his sociopolitical novels. From 1930 until 1933, he was president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy ...

's novel ''Man of Straw'' ().

scars are repeatedly noted and described as a sign of beauty and manliness by German characters in Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter (May 15, 1890 – September 18, 1980) was an American journalist, essayist, short story writer, novelist, poet, and political activist. Her 1962 novel '' Ship of Fools'' was the best-selling novel in the United States that y ...

's novel ''Ship of Fools''.

scars are mentioned in passing in Robert Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein ( ; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific acc ...

's ''Starship Troopers

''Starship Troopers'' is a military science fiction novel by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. Written in a few weeks in reaction to the US suspending nuclear tests, the story was first published as a two-part serial in ''The Magazine of ...

'' when two German recruits are asked at the beginning of boot camp where they got their scars. The drill sergeant even uses the term (as spelled in modern German). E. C. Gordon, the hero of Heinlein's '' Glory Road'', mentions his desire for a degree from Heidelberg and the dueling scars to go with it.

In the James Bond

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

books by Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer, best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., and his ...

, the supervillain

A supervillain, supervillainess or supercriminal is a major antagonist and variant of the villainous stock character who possesses Superpower (ability), superpowers. The character type is sometimes found in comic books and is often the primary ...

Ernst Stavro Blofeld

Ernst Stavro Blofeld is a fictional supervillain in the ''James Bond'' series of novels and films, created by Ian Fleming. A criminal mastermind with aspirations of world domination, he is the archenemy of British MI6 agent James Bond. Blofel ...

has a dueling scar below his eye.

Film

The is featured in a number of German films, notably: * (''Hans Westmar – One of Many''), 1933 *, 1951 and less commonly in films outside Germany, such as *''The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

''The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp'' is a 1943 British romantic-war film written, produced and directed by the British film-making team of Powell and Pressburger, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. It stars Roger Livesey, Deborah Kerr and ...

'', 1943

Television

* In episode 77 of Roald Dahl's '' Tales of the Unexpected'', "The Vorpal Blade", the story revolves around duelling of this kind * In ''Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in t ...

'', dueling is shown and many characters have scars from dueling.

See also

*German school of fencing

The German school of fencing (') is a system of combat taught in the Holy Roman Empire during the Late Medieval, German Renaissance, and early modern periods. It is described in the contemporary Fechtbücher ("fencing books") written at the ti ...

* Dueling scars

Dueling scars () have been seen as a "badge of honour" since as early as 1825. Known variously as " scars", "the bragging scar", "smite", "", or "", dueling scars were popular amongst upper class Germans and Austrians involved in academic fencing ...

* Fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

References

References (in German)

* Hermann Rink: ''Die Mensur, ein wesentliches Merkmal des Verbandes.'' In: Rolf-Joachim Baum (Hrsg.): ''„Wir wollen Männer, wir wollen Taten!“ Deutsche Corpsstudenten 1848 bis heute.'' Siedler, Berlin 1998. pages 383-402 * Hermann Rink: ''Vom studentischen Fechten bis zur Mensur.'' In: ''Handbuch des Kösener Corpsstudenten.'' Verband Alter Corpsstudenten e.V. Volume I. Würzburg 1985 (6. edition), pages 151-171 * Martin Biastoch: ''Duell und Mensur im Kaiserreich (am Beispiel der Tübinger Corps Franconia, Rhenania, Suevia und Borussia zwischen 1871 und 1895).'' SH-Verlag, Vierow 1995. *Wilhelm Fabricius

Wilhelm may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* William Charles John Pitcher, costume designer known professionally as "Wilhelm"

* Wilhelm (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

Other uses

* Wilhe ...

: ''Die Deutschen Corps. Eine historische Darstellung mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Mensurwesens''. Berlin 1898 (2. edition 1926)

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Academic Fencing Fencing Historical fencing Student societies in Germany College sports Blood sports