Menopausal Hormone Therapy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT), also known as menopausal hormone therapy or postmenopausal hormone therapy, is a form of

HRT can help with the lack of sexual desire and sexual dysfunction that can occur with menopause. Epidemiological surveys of women between 40 and 69 years suggest that 75% of women remain sexually active after menopause. With increasing life spans, women today are living one third or more of their lives in a postmenopausal state, a period during which healthy sexuality can be integral to their quality of life.

Decreased libido and sexual dysfunction are common issues in postmenopausal women, an entity referred to hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD); its signs and symptoms can both be improved by HRT. Several hormonal changes take place during this period, including a decrease in estrogen and an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone. For most women, the majority of change occurs during the late perimenopausal and postmenopausal stages. Decreases in sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and inhibin (A and B) also occur. Testosterone is present in women at a lower level than men, peaking at age 30 and declining gradually with age; there is less variation during the menopausal transition relative to estrogen and progesterone.

A global consensus position statement has advised that postmenopausal testosterone replacement to premenopausal levels can be effective for HSDD. Safety information for testosterone treatment is not available beyond two years of continuous therapy however and dosing above physiologic levels is not advised. Testosterone patches have been found to restore sexual desire in post menopausal women. There is insufficient data to evaluate the impact of testosterone replacement on heart disease, breast cancer, with most trials having included women taking concomitant estrogen and progesterone and with testosterone therapy itself being relatively short in duration. In the setting of this limited data, testosterone therapy has not been associated with adverse events.

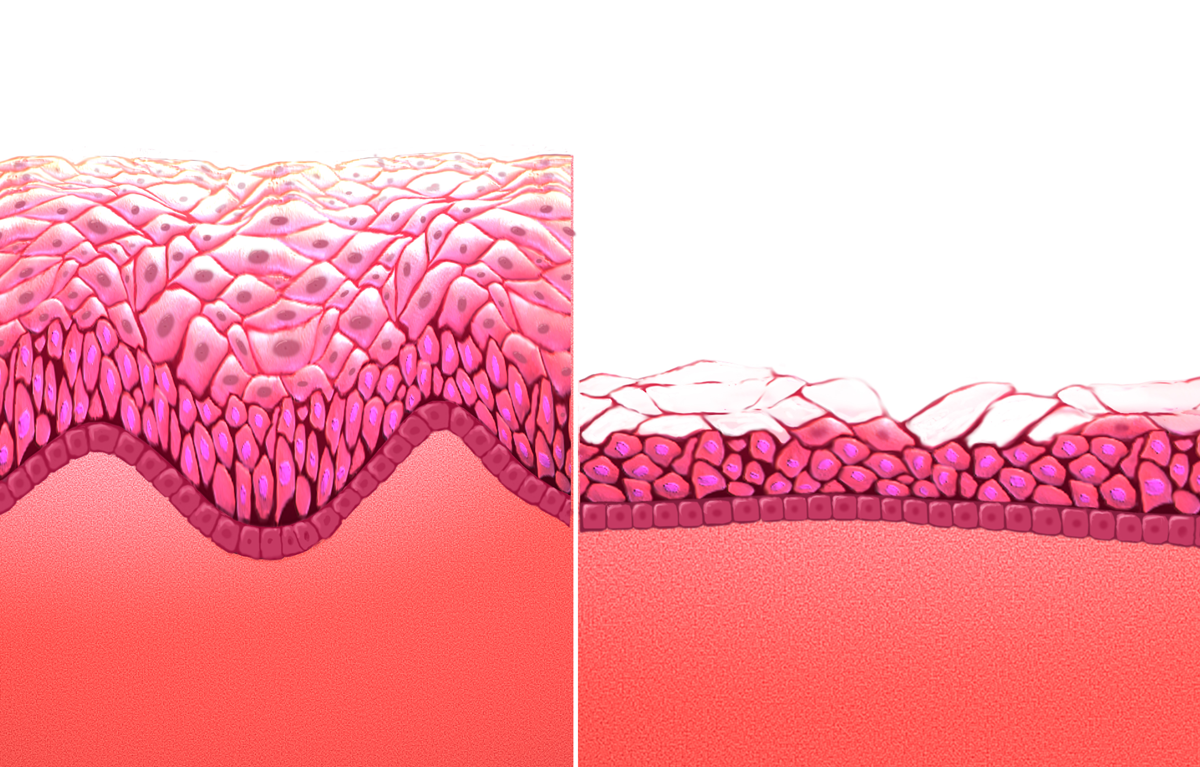

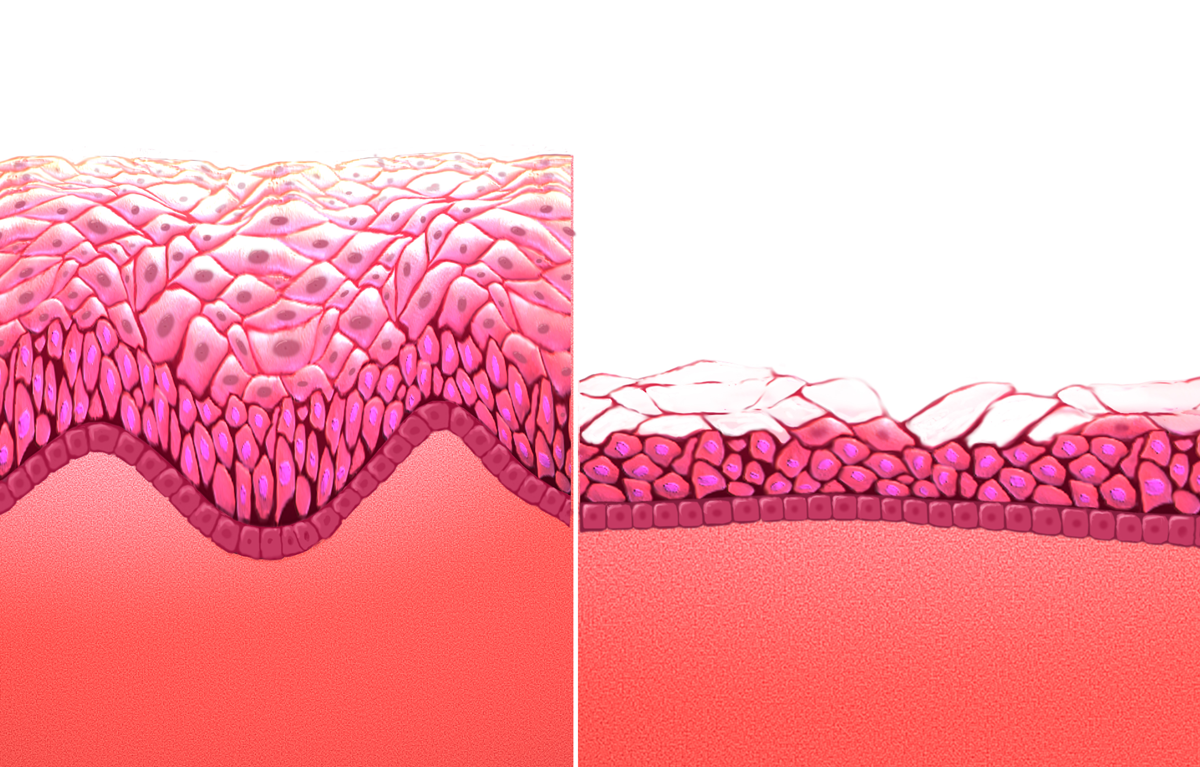

Not all women are responsive, especially those with preexisting sexual difficulties. Estrogen replacement can restore vaginal cells, pH levels, and blood flow to the vagina, all of which tend to deteriorate at the onset of menopause. Pain or discomfort with sex appears to be the most responsive component to estrogen. It also has been shown to have positive effects on the urinary tract. Estrogen can also reduce vaginal atrophy and increase sexual arousal, frequency and orgasm.

The effectiveness of hormone replacement can decline in some women after long-term use. A number of studies have also found that the combined effects of estrogen/androgen replacement therapy can increase libido and arousal over estrogen alone. Tibolone, a synthetic steroid with estrogenic, androgenic, and progestogenic properties that is available in Europe, has the ability to improve mood, libido, and physical symptomatology. In various placebo-controlled studies, improvements in vasomotor symptoms, emotional response, sleep disturbances, physical symptoms, and sexual desire have been seen, though it also carries a similar risk profile to conventional HRT.

HRT can help with the lack of sexual desire and sexual dysfunction that can occur with menopause. Epidemiological surveys of women between 40 and 69 years suggest that 75% of women remain sexually active after menopause. With increasing life spans, women today are living one third or more of their lives in a postmenopausal state, a period during which healthy sexuality can be integral to their quality of life.

Decreased libido and sexual dysfunction are common issues in postmenopausal women, an entity referred to hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD); its signs and symptoms can both be improved by HRT. Several hormonal changes take place during this period, including a decrease in estrogen and an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone. For most women, the majority of change occurs during the late perimenopausal and postmenopausal stages. Decreases in sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and inhibin (A and B) also occur. Testosterone is present in women at a lower level than men, peaking at age 30 and declining gradually with age; there is less variation during the menopausal transition relative to estrogen and progesterone.

A global consensus position statement has advised that postmenopausal testosterone replacement to premenopausal levels can be effective for HSDD. Safety information for testosterone treatment is not available beyond two years of continuous therapy however and dosing above physiologic levels is not advised. Testosterone patches have been found to restore sexual desire in post menopausal women. There is insufficient data to evaluate the impact of testosterone replacement on heart disease, breast cancer, with most trials having included women taking concomitant estrogen and progesterone and with testosterone therapy itself being relatively short in duration. In the setting of this limited data, testosterone therapy has not been associated with adverse events.

Not all women are responsive, especially those with preexisting sexual difficulties. Estrogen replacement can restore vaginal cells, pH levels, and blood flow to the vagina, all of which tend to deteriorate at the onset of menopause. Pain or discomfort with sex appears to be the most responsive component to estrogen. It also has been shown to have positive effects on the urinary tract. Estrogen can also reduce vaginal atrophy and increase sexual arousal, frequency and orgasm.

The effectiveness of hormone replacement can decline in some women after long-term use. A number of studies have also found that the combined effects of estrogen/androgen replacement therapy can increase libido and arousal over estrogen alone. Tibolone, a synthetic steroid with estrogenic, androgenic, and progestogenic properties that is available in Europe, has the ability to improve mood, libido, and physical symptomatology. In various placebo-controlled studies, improvements in vasomotor symptoms, emotional response, sleep disturbances, physical symptoms, and sexual desire have been seen, though it also carries a similar risk profile to conventional HRT.

The effect of HRT in menopause appears to be divergent, with lower risk of heart disease when started within five years, but no impact after ten. For women who are in early menopause and have no issues with their cardiovascular health, HRT comes with a low risk of adverse cardiovascular events. There may be an increase in heart disease if HRT is given twenty years post-menopause. This variability has led some reviews to suggest an absence of significant effect on morbidity. Importantly, there is no difference in long-term mortality from HRT, regardless of age.

A Cochrane review suggested that women starting HRT less than 10 years after menopause had lower mortality and coronary heart disease, without any strong effect on the risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism. Those starting therapy more than 10 years after menopause showed little effect on mortality and coronary heart disease, but an increased risk of stroke. Both therapies had an association with venous clots and pulmonary embolism.

HRT with estrogen and progesterone also improves cholesterol levels. With menopause, HDL decreases, while LDL, triglycerides and lipoprotein a increase, patterns that reverse with estrogen. Beyond this, HRT improves heart contraction, coronary blood flow,

The effect of HRT in menopause appears to be divergent, with lower risk of heart disease when started within five years, but no impact after ten. For women who are in early menopause and have no issues with their cardiovascular health, HRT comes with a low risk of adverse cardiovascular events. There may be an increase in heart disease if HRT is given twenty years post-menopause. This variability has led some reviews to suggest an absence of significant effect on morbidity. Importantly, there is no difference in long-term mortality from HRT, regardless of age.

A Cochrane review suggested that women starting HRT less than 10 years after menopause had lower mortality and coronary heart disease, without any strong effect on the risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism. Those starting therapy more than 10 years after menopause showed little effect on mortality and coronary heart disease, but an increased risk of stroke. Both therapies had an association with venous clots and pulmonary embolism.

HRT with estrogen and progesterone also improves cholesterol levels. With menopause, HDL decreases, while LDL, triglycerides and lipoprotein a increase, patterns that reverse with estrogen. Beyond this, HRT improves heart contraction, coronary blood flow,

from Mayo Clinic / Thomson Healthcare Inc. Portions of this document last updated: 1 November 2011 Sometimes an androgen, generally testosterone, can be added to treat diminished libido.

Menopause treatment

Hormone Health Network, The Endocrine Society

Sexual Health and Menopause Online

The North American Menopause Society

Menopause

US Food and Drug Administration

British Menopause Society

{{Androgens and antiandrogens Endocrine procedures Life sciences industry Menopause Obstetrical and gynaecological procedures IARC Group 1 carcinogens pl:Hormonalna terapia zastępcza

hormone therapy

Hormone therapy or hormonal therapy is the use of hormones in medical treatment. Treatment with hormone antagonists may also be referred to as hormonal therapy or antihormone therapy. The most general classes of hormone therapy are hormonal therap ...

used to treat symptoms associated with female menopause. Effects of menopause can include symptoms such as hot flashes, accelerated skin aging, vaginal dryness, decreased muscle mass, and complications such as osteoporosis (bone loss), sexual dysfunction, and vaginal atrophy. They are mostly caused by low levels of female sex hormones (e.g. estrogens) that occur during menopause.

Estrogens and progestogens are the main hormone drugs used in HRT. Progesterone is the main female sex hormone that occurs naturally and is also manufactured into a drug that is used in menopausal hormone therapy. Although both classes of hormones can have symptomatic benefit, progestogen is specifically added to estrogen regimens, unless the uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', : uteri or uteruses) or womb () is the hollow organ, organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans, that accommodates the embryonic development, embryonic and prenatal development, f ...

has been removed, to avoid the increased risk of endometrial cancer. Unopposed estrogen therapy promotes endometrial hyperplasia and increases the risk of cancer, while progestogen reduces this risk. Androgen

An androgen (from Greek ''andr-'', the stem of the word meaning ) is any natural or synthetic steroid hormone that regulates the development and maintenance of male characteristics in vertebrates by binding to androgen receptors. This includes ...

s like testosterone are sometimes used as well. HRT is available through a variety of different routes.

The long-term effects of HRT on most organ systems vary by age and time since the last physiological exposure to hormones, and there can be large differences in individual regimens, factors which have made analyzing effects difficult. The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) is an ongoing study of over 27,000 women that began in 1991, with the most recent analyses suggesting that, when initiated within 10 years of menopause, HRT reduces all-cause mortality and risks of coronary disease, osteoporosis, and dementia; after 10 years the beneficial effects on mortality and coronary heart disease are no longer apparent, though there are decreased risks of hip and vertebral fractures and an increased risk of venous thromboembolism when taken orally.

"Bioidentical" hormone replacement is a development in the 21st century and uses manufactured compounds with "exactly the same chemical and molecular structure as hormones that are produced in the human body." These are mainly manufactured from plant steroids and can be a component of either registered ''pharmaceutical'' or custom-made ''compounded'' preparations, with the latter generally not recommended by regulatory bodies due to their lack of standardization and formal oversight. Bioidentical hormone replacement has inadequate clinical research to determine its safety and efficacy as of 2017.

The current indications for use from the United States Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

(FDA) include short-term treatment of menopausal symptoms, such as vasomotor hot flashes or vaginal atrophy, and prevention of osteoporosis.

Medical uses

Approved uses of HRT in the United States include short-term treatment of menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and vaginal atrophy, and prevention of osteoporosis. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) approves of HRT for symptomatic relief of menopausal symptoms, and advocates its use beyond the age of 65 in appropriate scenarios. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2016 annual meeting mentioned that HRT may have more benefits than risks in women before the age of 60. A consensus expert opinion published by The Endocrine Society stated that when taken during perimenopause or the initial years of menopause, HRT carries fewer risks than previously published, and reduces all cause mortality in most scenarios. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) has also released position statements approving of HRT when appropriate. Women receiving this treatment are usually post-, peri-, or surgically induced menopausal. Menopause is the permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from loss of ovarian follicular activity, defined as beginning twelve months after the final natural menstrual cycle. This twelve month time point divides menopause into early and late transition periods known as 'perimenopause' and 'postmenopause'. Premature menopause can occur if the ovaries are surgically removed, as can be done to treat ovarian or uterine cancer. Demographically, the vast majority of data available is in postmenopausal American women with concurrent pre-existing conditions and an average age of over 60 years.Menopausal symptoms

HRT is often given as a short-term relief from menopausal symptoms during perimenopause. Potential menopausal symptoms include: * Hot flashes – vasomotor symptoms * Vulvovaginal atrophy – atrophic vaginitis and dryness * Dyspareunia – painful sexual intercourse due to vaginal atrophy and lack of lubrication * Bone loss – decreased bone mineral density, which can eventually lead to osteopenia, osteoporosis, and associated fractures * Decreased sexual desire * Defeminization – diminished feminine fat distribution and accelerated skin aging * Sleep disturbances and joint pain The most common of these are loss of sexual drive and vaginal dryness.Sarrel, P.M. (2000). Effects of hormone replacement therapy on sexual psychophysiology and behavior in postmenopause. Journal of Women's Health and Gender-Based Medicine, 9, 25–32 The use of hormone therapy for heart health among menopausal women has declined significantly over the past few decades. In 1999, nearly 27% of menopausal women in the U.S. used estrogen, but by 2020, that figure had dropped to less than 5%. Recent evidence in 2024 suggests evidence supporting the cardiovascular benefits of hormone therapy, including improvements in insulin resistance and other heart-related markers. This adds to a growing body of research highlighting hormone therapy’s effectiveness, not only for heart health but also for managing menopausal symptoms like hot flashes, disrupted sleep, vaginal dryness, and painful intercourse. Despite its proven benefits, many menopausal women avoid hormone therapy, often due to lingering misconceptions about its risks and societal discomfort with openly discussing menopause.Sexual function

HRT can help with the lack of sexual desire and sexual dysfunction that can occur with menopause. Epidemiological surveys of women between 40 and 69 years suggest that 75% of women remain sexually active after menopause. With increasing life spans, women today are living one third or more of their lives in a postmenopausal state, a period during which healthy sexuality can be integral to their quality of life.

Decreased libido and sexual dysfunction are common issues in postmenopausal women, an entity referred to hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD); its signs and symptoms can both be improved by HRT. Several hormonal changes take place during this period, including a decrease in estrogen and an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone. For most women, the majority of change occurs during the late perimenopausal and postmenopausal stages. Decreases in sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and inhibin (A and B) also occur. Testosterone is present in women at a lower level than men, peaking at age 30 and declining gradually with age; there is less variation during the menopausal transition relative to estrogen and progesterone.

A global consensus position statement has advised that postmenopausal testosterone replacement to premenopausal levels can be effective for HSDD. Safety information for testosterone treatment is not available beyond two years of continuous therapy however and dosing above physiologic levels is not advised. Testosterone patches have been found to restore sexual desire in post menopausal women. There is insufficient data to evaluate the impact of testosterone replacement on heart disease, breast cancer, with most trials having included women taking concomitant estrogen and progesterone and with testosterone therapy itself being relatively short in duration. In the setting of this limited data, testosterone therapy has not been associated with adverse events.

Not all women are responsive, especially those with preexisting sexual difficulties. Estrogen replacement can restore vaginal cells, pH levels, and blood flow to the vagina, all of which tend to deteriorate at the onset of menopause. Pain or discomfort with sex appears to be the most responsive component to estrogen. It also has been shown to have positive effects on the urinary tract. Estrogen can also reduce vaginal atrophy and increase sexual arousal, frequency and orgasm.

The effectiveness of hormone replacement can decline in some women after long-term use. A number of studies have also found that the combined effects of estrogen/androgen replacement therapy can increase libido and arousal over estrogen alone. Tibolone, a synthetic steroid with estrogenic, androgenic, and progestogenic properties that is available in Europe, has the ability to improve mood, libido, and physical symptomatology. In various placebo-controlled studies, improvements in vasomotor symptoms, emotional response, sleep disturbances, physical symptoms, and sexual desire have been seen, though it also carries a similar risk profile to conventional HRT.

HRT can help with the lack of sexual desire and sexual dysfunction that can occur with menopause. Epidemiological surveys of women between 40 and 69 years suggest that 75% of women remain sexually active after menopause. With increasing life spans, women today are living one third or more of their lives in a postmenopausal state, a period during which healthy sexuality can be integral to their quality of life.

Decreased libido and sexual dysfunction are common issues in postmenopausal women, an entity referred to hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD); its signs and symptoms can both be improved by HRT. Several hormonal changes take place during this period, including a decrease in estrogen and an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone. For most women, the majority of change occurs during the late perimenopausal and postmenopausal stages. Decreases in sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and inhibin (A and B) also occur. Testosterone is present in women at a lower level than men, peaking at age 30 and declining gradually with age; there is less variation during the menopausal transition relative to estrogen and progesterone.

A global consensus position statement has advised that postmenopausal testosterone replacement to premenopausal levels can be effective for HSDD. Safety information for testosterone treatment is not available beyond two years of continuous therapy however and dosing above physiologic levels is not advised. Testosterone patches have been found to restore sexual desire in post menopausal women. There is insufficient data to evaluate the impact of testosterone replacement on heart disease, breast cancer, with most trials having included women taking concomitant estrogen and progesterone and with testosterone therapy itself being relatively short in duration. In the setting of this limited data, testosterone therapy has not been associated with adverse events.

Not all women are responsive, especially those with preexisting sexual difficulties. Estrogen replacement can restore vaginal cells, pH levels, and blood flow to the vagina, all of which tend to deteriorate at the onset of menopause. Pain or discomfort with sex appears to be the most responsive component to estrogen. It also has been shown to have positive effects on the urinary tract. Estrogen can also reduce vaginal atrophy and increase sexual arousal, frequency and orgasm.

The effectiveness of hormone replacement can decline in some women after long-term use. A number of studies have also found that the combined effects of estrogen/androgen replacement therapy can increase libido and arousal over estrogen alone. Tibolone, a synthetic steroid with estrogenic, androgenic, and progestogenic properties that is available in Europe, has the ability to improve mood, libido, and physical symptomatology. In various placebo-controlled studies, improvements in vasomotor symptoms, emotional response, sleep disturbances, physical symptoms, and sexual desire have been seen, though it also carries a similar risk profile to conventional HRT.

Muscle and bone

There is a significant decrease in hip fracture risk during treatment that to a lesser degree persists after HRT is stopped. It also helps collagen formation, which in turn improves intervertebral disc and bone strength. Hormone replacement therapy in the form of estrogen and androgen can be effective at reversing the effects of aging on muscle. Lower testosterone is associated with lower bone density and higher free testosterone is associated with lower hip fracture rates in older women. Testosterone therapy, which can be used for decreased sexual function, can also increase bone mineral density and muscle mass.Side effects

Side effects in HRT occur with varying frequency and include:Common

* Headache * Upset stomach, stomach cramps or bloating * Diarrhea * Appetite and weight changes * Changes in sex drive or performance * Nervousness * Brown or black patches on the skin * Acne * Swelling of hands, feet, or lower legs due to fluid retention * Changes in menstrual flow * Breast tenderness, enlargement, or discharge * Sudden difficulty wearing contact lensesUncommon

* Double vision * Severe abdominal pain * Yellowing of skin or eyes * Severe depression * Unusual bleeding * Loss of appetite * Skin rash * Lassitude * Fever * Dark-colored urine * Light colored stool * ChoreaHealth effects

Heart disease

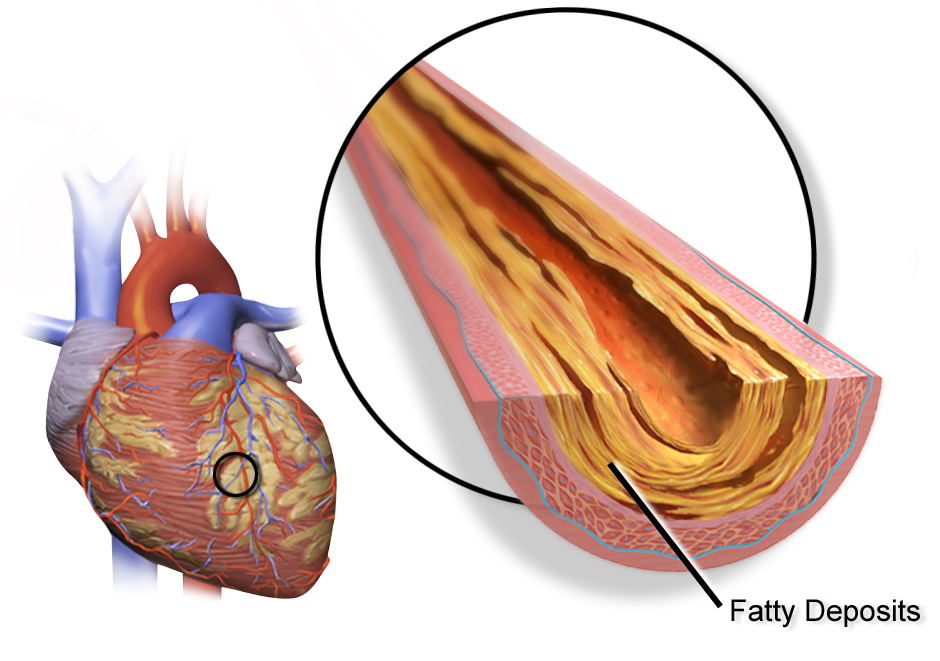

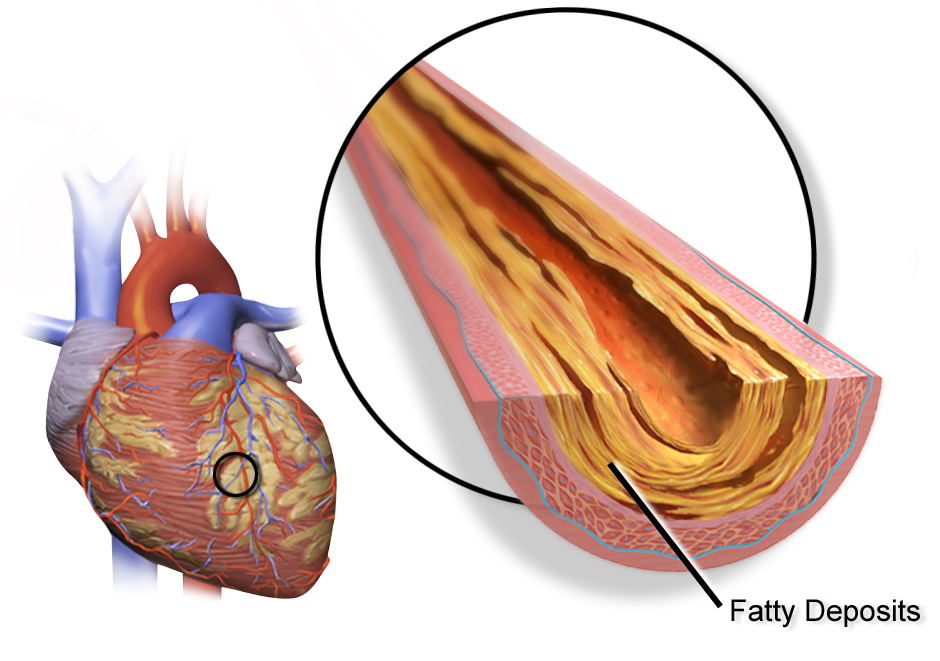

The effect of HRT in menopause appears to be divergent, with lower risk of heart disease when started within five years, but no impact after ten. For women who are in early menopause and have no issues with their cardiovascular health, HRT comes with a low risk of adverse cardiovascular events. There may be an increase in heart disease if HRT is given twenty years post-menopause. This variability has led some reviews to suggest an absence of significant effect on morbidity. Importantly, there is no difference in long-term mortality from HRT, regardless of age.

A Cochrane review suggested that women starting HRT less than 10 years after menopause had lower mortality and coronary heart disease, without any strong effect on the risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism. Those starting therapy more than 10 years after menopause showed little effect on mortality and coronary heart disease, but an increased risk of stroke. Both therapies had an association with venous clots and pulmonary embolism.

HRT with estrogen and progesterone also improves cholesterol levels. With menopause, HDL decreases, while LDL, triglycerides and lipoprotein a increase, patterns that reverse with estrogen. Beyond this, HRT improves heart contraction, coronary blood flow,

The effect of HRT in menopause appears to be divergent, with lower risk of heart disease when started within five years, but no impact after ten. For women who are in early menopause and have no issues with their cardiovascular health, HRT comes with a low risk of adverse cardiovascular events. There may be an increase in heart disease if HRT is given twenty years post-menopause. This variability has led some reviews to suggest an absence of significant effect on morbidity. Importantly, there is no difference in long-term mortality from HRT, regardless of age.

A Cochrane review suggested that women starting HRT less than 10 years after menopause had lower mortality and coronary heart disease, without any strong effect on the risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism. Those starting therapy more than 10 years after menopause showed little effect on mortality and coronary heart disease, but an increased risk of stroke. Both therapies had an association with venous clots and pulmonary embolism.

HRT with estrogen and progesterone also improves cholesterol levels. With menopause, HDL decreases, while LDL, triglycerides and lipoprotein a increase, patterns that reverse with estrogen. Beyond this, HRT improves heart contraction, coronary blood flow, sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

metabolism, and decreases platelet

Platelets or thrombocytes () are a part of blood whose function (along with the coagulation#Coagulation factors, coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping to form a thrombus, blood clot. Platelets have no ...

aggregation and plaque formation. HRT may promote reverse cholesterol transport through induction of cholesterol ABC transporters. Atherosclerosis imaging trials show that HRT decreases the formation of new vascular lesions, but does not reverse the progression of existing lesions. HRT also results in a large reduction in the pro-thrombotic lipoprotein a.

Studies on cardiovascular disease with testosterone therapy have been mixed, with some suggesting no effect or a mild negative effect, though others have shown an improvement in surrogate markers such as cholesterol, triglycerides and weight. Testosterone has a positive effect on vascular endothelial function and tone with observational studies suggesting that women with lower testosterone may be at greater risk for heart disease. Available studies are limited by small sample size and study design. Low sex hormone-binding globulin, which occurs with menopause, is associated with increased body mass index and risk for type 2 diabetes.

Blood clots

Effects of hormone replacement therapy on venous blood clot formation and potential for pulmonary embolism may vary with different estrogen and progestogen therapies, and with different doses or method of use. Comparisons between routes of administration suggest that when estrogens are applied to the skin or vagina, there is a lower risk of blood clots, whereas when used orally, the risk of blood clots and pulmonary embolism is increased. Skin and vaginal routes of hormone therapy are not subject to first pass metabolism, and so lack the anabolic effects that oral therapy has on liver synthesis ofvitamin K

Vitamin K is a family of structurally similar, fat-soluble vitamers found in foods and marketed as dietary supplements. The human body requires vitamin K for post-translational modification, post-synthesis modification of certain proteins ...

-dependent clotting factors, possibly explaining why oral therapy may increase blood clot formation.

While a 2018 review found that taking progesterone and estrogen together can decrease this risk, other reviews reported an increased risk of blood clots and pulmonary embolism when estrogen and progestogen were combined, particularly when treatment was started 10 years or more after menopause and when the women were older than 60 years.

The risk of venous thromboembolism may be reduced with bioidentical preparations, though research on this is only preliminary.Stroke

Multiple studies suggest that the possibility of HRT related stroke is absent if therapy is started within five years of menopause, and that the association is absent or even preventive when given by non-oral routes. Ischemic stroke risk was increased during the time of intervention in the WHI, with no significant effect after the cessation of therapy and no difference in mortality at long term follow up. When oral synthetic estrogen or combined estrogen-progestogen treatment is delayed until five years from menopause, cohort studies in Swedish women have suggested an association with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. Another large cohort of Danish women suggested that the specific route of administration was important, finding that although oral estrogen increased risk of stroke, absorption through the skin had no impact, and vaginal estrogen actually had a decreased risk.Endometrial cancer

In postmenopausal women, continuous combined estrogen plus progestin decreases endometrial cancer incidence. The duration of progestogen therapy should be at least 14 days per cycle to prevent endometrial disease. Endometrial cancer has been grouped into two forms in the context of hormone replacement. Type 1 is the most common, can be associated with estrogen therapy, and is usually low grade. Type 2 is not related to estrogen stimulation and usually higher grade and poorer in prognosis. The endometrial hyperplasia that leads to endometrial cancer with estrogen therapy can be prevented by concomitant administration of progestogen. The extensive use of high-dose estrogens for birth control in the 1970s is thought to have resulted in a significant increase in the incidence of type 1 endometrial cancer. Paradoxically, progestogens do promote the growth of uterine fibroids, and a pelvic ultrasound can be performed before beginning HRT to make sure there are no underlying uterine or endometrial lesions. Androgens do not stimulate endometrial proliferation in post menopausal women, and appear to inhibit the proliferation induced by estrogen to a certain extent. There is insufficient high‐quality evidence to inform women considering hormone replacement therapy after treatment for endometrial cancer.Breast cancer

In general, hormone replacement therapy to treat menopause is associated with only a small increased risk of breast cancer. The level of risk also depends on the type of HRT, the duration of the treatment and the age of the person. Oestrogen-only HRT, taken by people who had a hysterectomy, comes with an extremely low level of breast cancer risk. The most commonly taken combined HRT (oestrogen and progestogen) is linked to a small risk of breast cancer. This risk is lower for women in their 50s and higher for older women. The risk increases with the duration of HRT. When HRT is taken for a year or less, there is no increased risk of breast cancer. HRT taken for more than 5 years comes with an increased risk but the risk reduces after the therapy is stopped. There is a non-statistically significant increased rate of breast cancer for hormone replacement therapy with synthetic progestogens. The risk may be reduced with bioidentical progesterone, though the only prospective study that suggested this was underpowered due to the rarity of breast cancer in the control population. There have been no randomized controlled trials as of 2018. The relative risk of breast cancer also varies depending on the interval between menopause and HRT and route of synthetic progestin administration. The most recent follow up of the Women's Health Initiative participants demonstrated a lower incidence of breast cancer in post-hysterectomy participants taking equine estrogen alone, though the relative risk was increased if estrogen was taken with medroxyprogesterone. Estrogen is usually only given alone in the setting of a hysterectomy due to the increased risk of vaginal bleeding and uterine cancer with unopposed estrogen. HRT has been more strongly associated with risk of breast cancer in women with lower body mass indices (BMIs). No breast cancer association has been found with BMIs of over 25. It has been suggested by some that the absence of significant effect in some of these studies could be due to selective prescription to overweight women who have higher baseline estrone, or to the very low progesterone serum levels after oral administration leading to a high tumor inactivation rate. Evaluating the response of breast tissue density to HRT using mammography appears to help assessing the degree of breast cancer risk associated with therapy; women with dense or mixed- dense breast tissue have a higher risk of developing breast cancer than those with low density tissue. Micronized progesterone does not appear to be associated with breast cancer risk when used for less than five years with limited data suggesting an increased risk when used for longer duration. For women who previously have had breast cancer, it is recommended to first consider other options for menopausal effects, such as bisphosphonates or selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for osteoporosis, cholesterol-lowering agents and aspirin for cardiovascular disease, and vaginal estrogen for local symptoms. Observational studies of systemic HRT after breast cancer are generally reassuring. If HRT is necessary after breast cancer, estrogen-only therapy or estrogen therapy with a progestogen may be safer options than combined systemic therapy. In women who are BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers, HRT does not appear to impact breast cancer risk. The relative number of women using HRT who also obtain regular screening mammograms is higher than that in women who do not use HRT, a factor which has been suggested as contributing to different breast cancer detection rates in the two groups. With androgen therapy, pre-clinical studies have suggested an inhibitory effect on breast tissue though the majority of epidemiological studies suggest a positive association.Ovarian cancer

HRT is associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer, with women using HRT having about one additional case of ovarian cancer per 1,000 users. This risk is decreased when progestogen therapy is given concomitantly, as opposed to estrogen alone, and also decreases with increasing time since stopping HRT. Regarding the specific subtype, there may be a higher risk of serous cancer, but no association with clear cell, endometrioid, or mucinous ovarian cancer. Hormonal therapy in ovarian cancer survivors after surgical removal of the ovaries is generally thought to improval survival rates.Other cancers

Colorectal cancer

In the WHI, women who took combined estrogen-progesterone therapy had a lower risk of getting colorectal cancer. However, the cancers they did have were more likely to have spread to lymph nodes or distant sites than colorectal cancer in women not taking hormones. In colorectal cancer survivors, usage of HRT is thought to lead to lower recurrence risk and overall mortality.Cervical cancer

There appears to be a significantly decreased risk of cervical squamous cell cancer in post menopausal women treated with HRT and a weak increase in adenocarcinoma. No studies have reported an increased risk of recurrence when HRT is used with cervical cancer survivors.Neurodegenerative disorders

As of 2024 there has been conflicting evidence from clinical studies regarding the beneficial effects of estrogens at reducing the risk of Alzheimer's Disease. For prevention, the WHI suggested in 2013, that HRT may increase risk of dementia if initiated after 65 years of age, but have a neutral outcome or be neuroprotective for those between 50 and 55 years. However, the prospective ELITE trial showed negligible effects on verbal memory and other mental skills regardless of how soon after menopause a woman began HRT. A 2012 review of clinical and epidemiological studies of HRT and AD, PD, FTD and HIV related dementia concluded results were inconclusive at this time. The majority of clinical and epidemiological studies show either no association with the risk of developing Parkinson's disease or inconclusive results. One Danish study suggested an increased risk of Parkinson's with HRT in cyclical dosing schedules. Other randomized trials have shown HRT to improve executive and attention processes outside of the context of dementia in postmenopausal women, both in asymptomatic and those with mild cognitive impairment. As of 2011, estrogen replacement in post menopausal women with Parkinson's disease appeared to improve motor symptoms and activities of daily living , with significant improvement of UPDRS scores. Testosterone replacement has also shown to be associated with small statistically significant improvements in verbal learning and memory in postmenopausal women but DHEA has not been found to improve cognitive performance after menopause. Pre-clinical studies have indicated that endogenous estrogen and testosterone are neuroprotective and can prevent brain amyloid deposition.Contraindications

The following are absolute and relative contraindications to HRT:Absolute contraindications

* Undiagnosed vaginal bleeding * Severe liver disease * Pregnancy * Severe coronary artery disease * Aggressive breast, uterine or ovarian cancerRelative contraindications

* Migraine headaches * History of breast cancer * History of ovarian cancer * Venous thrombosis * History of uterine fibroids * Atypical ductal hyperplasia of the breast * Active gallbladder disease ( cholangitis, cholecystitis) * Well-differentiated and early endometrial cancer – once treatment for the malignancy is complete, is no longer an absolute contraindication.History and research

The extraction of CEEs from the urine of pregnant mares led to the marketing in 1942 of Premarin, one of the earlier forms of estrogen to be introduced. From that time until the mid-1970s, estrogen was administered without a supplemental progestogen. Beginning in 1975, studies began to show that without a progestogen, unopposed estrogen therapy with Premarin resulted in an eight-fold increased risk of endometrial cancer, eventually causing sales of Premarin to plummet. It was recognized in the early 1980s that the addition of a progestogen to estrogen reduced this risk to the endometrium. This led to the development of combined estrogen–progestogen therapy, most commonly with a combination of conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin) and medroxyprogesterone (Provera).Trials

The Women's Health Initiative trials were conducted between 1991 and 2006 and were the first large, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of HRT in healthy women. Their results were both positive and negative, suggesting that during the time of hormone therapy itself, there are increases in invasive breast cancer, stroke and lung clots. Other risks include increased endometrial cancer, gallbladder disease, and urinary incontinence, while benefits include decreased hip fractures, decreased incidence of diabetes, and improvement of vasomotor symptoms. There is also an increased risk ofdementia

Dementia is a syndrome associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by a general decline in cognitive abilities that affects a person's ability to perform activities of daily living, everyday activities. This typically invo ...

with HRT in women over 65, though at younger ages it appears to be neuroprotective. After the cessation of HRT, the WHI continued to observe its participants, and found that most of these risks and benefits dissipated, though some elevation in breast cancer risk did persist. Other studies have also suggested an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

The arm of the WHI receiving combined estrogen and progestin therapy was closed prematurely in 2002 by its Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) due to perceived health risks, though this occurred a full year after the data suggesting increased risk became manifest. In 2004, the arm of the WHI in which post-hysterectomy patients were being treated with estrogen alone was also closed by the DMC. Clinical medical practice changed based upon two parallel Women's Health Initiative (WHI) studies of HRT. Prior studies were smaller, and many were of women who electively took hormonal therapy. One portion of the parallel studies followed over 16,000 women for an average of 5.2 years, half of whom took placebo, while the other half took a combination of CEEs and MPA (Prempro). This WHI estrogen-plus-progestin trial was stopped prematurely in 2002 because preliminary results suggested risks of combined CEEs and progestins exceeded their benefits. The first report on the halted WHI estrogen-plus-progestin study came out in July 2002.

Initial data from the WHI in 2002 suggested mortality to be lower when HRT was begun earlier, between age 50 to 59, but higher when begun after age 60. In older patients, there was an apparent increased incidence of breast cancer, heart attacks, venous thrombosis, and stroke, although a reduced incidence of colorectal cancer and bone fracture. At the time, The WHI recommended that women with non-surgical menopause take the lowest feasible dose of HRT for the shortest possible time to minimize associated risks. Some of the WHI findings were again found in a larger national study done in the United Kingdom, known as the Million Women Study (MWS). As a result of these findings, the number of women taking HRT dropped precipitously. In 2012, the United States Preventive Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that the harmful effects of combined estrogen and progestin therapy likely exceeded their chronic disease prevention benefits.

In 2002 when the first WHI follow up study was published, with HRT in post menopausal women, both older and younger age groups had a slightly higher incidence of breast cancer, and both heart attack and stroke were increased in older patients, although not in younger participants. Breast cancer was increased in women treated with estrogen and a progestin, but not with estrogen and progesterone or estrogen alone. Treatment with unopposed estrogen (i.e., an estrogen alone without a progestogen) is contraindicated if the uterus is still present, due to its proliferative effect on the endometrium. The WHI also found a reduced incidence of colorectal cancer when estrogen and a progestogen were used together, and most importantly, a reduced incidence of bone fractures. Ultimately, the study found disparate results for all cause mortality with HRT, finding it to be lower when HRT was begun during ages 50–59, but higher when begun after age 60. The authors of the study recommended that women with non-surgical menopause take the lowest feasible dose of hormones for the shortest time to minimize risk.

The data published by the WHI suggested supplemental estrogen increased risk of venous thromboembolism and breast cancer but was protective against osteoporosis and colorectal cancer, while the impact on cardiovascular disease was mixed. These results were later supported in trials from the United Kingdom, but not in more recent studies from France and China. Genetic polymorphism appears to be associated with inter-individual variability in metabolic response to HRT in postmenopausal women.

The WHI reported statistically significant increases in rates of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, strokes and pulmonary emboli. The study also found statistically significant decreases in rates of hip fracture and colorectal cancer. "A year after the study was stopped in 2002, an article was published indicating that estrogen plus progestin also increases the risks of dementia." The conclusion of the study was that the HRT combination presented risks that outweighed its measured benefits. The results were almost universally reported as risks and problems associated with HRT in general, rather than with Prempro, the specific proprietary combination of CEEs and MPA studied.

After the increased clotting found in the first WHI results was reported in 2002, the number of Prempro prescriptions filled reduced by almost half. Following the WHI results, a large percentage of HRT users opted out of them, which was quickly followed by a sharp drop in breast cancer rates. The decrease in breast cancer rates has continued in subsequent years. An unknown number of women started taking alternatives to Prempro, such as compounded bioidentical hormones, though researchers have asserted that compounded hormones are not significantly different from conventional hormone therapy.

The other portion of the parallel studies featured women who were post hysterectomy and so received either placebo progestogen or CEEs alone. This group did not show the risks demonstrated in the combination hormone study, and the estrogen-only study was not halted in 2002. However, in February 2004 it, too, was halted. While there was a 23% decreased incidence of breast cancer in the estrogen-only study participants, risks of stroke and pulmonary embolism were increased slightly, predominantly in patients who began HRT over the age of 60.

Several other large studies and meta-analyses have reported reduced mortality for HRT in women younger than age 60 or within 10 years of menopause, and a debatable or absent effect on mortality in women over 60.

Though research thus far has been substantial, further investigation is needed to fully understand differences in effect for different types of HRT and lengths of time since menopause. , for example, no trial has studied women who begin taking HRT around age 50 and continue taking it for longer than 10 years.

Available forms

There are five major human steroid hormones: estrogens, progestogens, androgens, mineralocorticoids, and glucocorticoids. Estrogens and progestogens are the two most often used in menopause. They are available in a wide variety of FDA approved and non–FDA-approved formulations. In women with intactuterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', : uteri or uteruses) or womb () is the hollow organ, organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans, that accommodates the embryonic development, embryonic and prenatal development, f ...

es, estrogens are almost always given in combination with progestogens, as long-term unopposed estrogen therapy is associated with a markedly increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. Conversely, in women who have undergone a hysterectomy or do not have a uterus, a progestogen is not required, and estrogen can be used alone. There are many combined formulations which include both estrogen and progestogen.

Specific types of hormone replacement include:

* Estrogens – bioidentical estrogens like estradiol and estriol, animal-derived estrogens like conjugated estrogens (CEEs), and synthetic estrogens like ethinylestradiol

* Progestogens – bioidentical progesterone, and progestins (synthetic progestogens) like medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), norethisterone, and dydrogesterone

* Androgen

An androgen (from Greek ''andr-'', the stem of the word meaning ) is any natural or synthetic steroid hormone that regulates the development and maintenance of male characteristics in vertebrates by binding to androgen receptors. This includes ...

s – bioidentical testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and synthetic anabolic steroid

Anabolic steroids, also known as anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS), are a class of drugs that are structurally related to testosterone, the main male sex hormone, and produce effects by binding to the androgen receptor (AR). Anabolism, Anaboli ...

s like methyltestosterone and nandrolone decanoate

Tibolone – a synthetic medication available in Europe but not the United States– is more effective than placebo but less effective than combination hormone therapy in postmenopausal women. It may have a decreased risk of breast and colorectal cancer, though conversely it can be associated with vaginal bleeding, endometrial cancer, and increase the risk of stroke in women over age 60 years.

Vaginal estrogen can improve local atrophy and dryness, with fewer systemic effects than estrogens delivered by other routes.Estrogen (Vaginal Route)from Mayo Clinic / Thomson Healthcare Inc. Portions of this document last updated: 1 November 2011 Sometimes an androgen, generally testosterone, can be added to treat diminished libido.

Continuous versus cyclic

Dosage is often varied cyclically to more closely mimic the ovarian hormone cycle, with estrogens taken daily and progestogens taken for about two weeks every month or every other month, a schedule referred to as 'cyclic' or 'sequentially combined'. Alternatively, 'continuous combined' HRT can be given with a constant daily hormonal dosage. Continuous combined HRT is associated with less complex endometrial hyerplasia than cyclic. Impact on breast density appears to be similar in both regimen timings.Route of administration

The medications used in menopausal HRT are available in numerous different formulations for use by a variety of different routes of administration: *Oral administration

Oral administration is a route of administration whereby a substance is taken through the Human mouth, mouth, swallowed, and then processed via the digestive system. This is a common route of administration for many medications.

Oral administ ...

– tablets, capsules

* Transdermal administration – patches, gels, creams

* Vaginal administration – tablets, creams, suppositories, rings

* Intramuscular or subcutaneous injection – solutions in vials or ampoules

* Subcutaneous implant – surgically-inserted pellets placed into fat tissue

* Less commonly sublingual, buccal, intranasal, and rectal administration, as well as intrauterine devices

More recently developed forms of drug delivery are alleged to have increased local effect lower dosing, fewer side effects, and constant rather than cyclical serum hormone levels. Transdermal and vaginal estrogen, in particular, avoid first pass metabolism through the liver. This in turn prevents an increase in clotting factors and accumulation of anti-estrogenic metabolites, resulting in fewer adverse side effects, particularly with regard to cardiovascular disease and stroke.

Injectable forms of estradiol exist and have been used occasionally in the past. However, they are rarely used in menopausal hormone therapy in modern times and are no longer recommended. Instead, other non-oral forms of estradiol such as transdermal estradiol are recommended and may be used. Estradiol injectables are generally well-tolerated and convenient, requiring infrequent administration. However, this form of estradiol does not release estradiol at a constant rate and there are very high circulating estradiol levels soon after injection followed by a rapid decline in levels. Injections may also be painful. Examples of estradiol injectables that may be used in menopausal hormone therapy include estradiol valerate and estradiol cypionate. In terms of injectable progestogens, injectable progesterone is associated with pain and injection site reactions as well as a short duration of action requiring very frequent injections, and is similarly not recommended in menopausal hormone therapy.

Bioidentical hormone therapy

Bioidentical hormone therapy (BHT) is the usage of hormones that are chemically identical to those produced in the body. Although proponents of BHT claim advantages over non-bioidentical or conventional hormone therapy, the FDA does not recognize the term 'bioidentical hormone', stating there is no scientific evidence that these hormones are identical to their naturally occurring counterparts. There are, however, FDA approved products containing hormones classified as 'bioidentical'. Bioidentical hormones can be used in either ''pharmaceutical'' or ''compounded'' preparations, with the latter generally not recommended by regulatory bodies due to their lack of standardization and regulatory oversight. Most classifications of bioidentical hormones do not take into account manufacturing, source, or delivery method of the products, and so describe both non-FDA approved compounded products and FDA approved pharmaceuticals as 'bioidentical'. The British Menopause Society has issued a consensus statement endorsing the distinction between "compounded" forms (cBHRT), described as unregulated, custom made by specialty pharmacies and subject to heavy marketing and "regulated" pharmaceutical grade forms (rBHRT), which undergo formal oversight by entities such as the FDA and form the basis of most clinical trials. Some practitioners recommending compounded bioidentical HRT also use salivary or serum hormonal testing to monitor response to therapy, a practice not endorsed by current clinical guidelines in the United States and Europe. Bioidentical hormones in pharmaceuticals may have very limited clinical data, with no randomized controlled prospective trials to date comparing them to their animal derived counterparts. Some pre-clinical data has suggested a decreased risk of venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer. As of 2012, guidelines from the North American Menopause Society, the Endocrine Society, the International Menopause Society, and the European Menopause and Andropause Society endorsed the reduced risk of bioidentical pharmaceuticals for those with increased clotting risk.Compounding

Compounding for HRT is generally discouraged by the FDA and medical industry in the United States due to a lack of regulation and standardized dosing. The U.S. Congress did grant the FDA explicit but limited oversight of compounded drugs in a 1997 amendment to theFederal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

The United States Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (abbreviated as FFDCA, FDCA, or FD&C) is a set of laws passed by the United States Congress in 1938 giving authority to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to oversee the food safety ...

(FDCA), but they have encountered obstacles in this role since that time. After 64 patient deaths and 750 harmed patients from a 2012 meningitis outbreak due to contaminated steroid injections, Congress passed the 2013 Drug Quality and Security Act, authorizing creation by the FDA of a voluntary registration for facilities that manufactured compounded drugs, and reinforcing FDCA regulations for traditional compounding. The DQSA and its reinforcement of provision §503A of the FDCA solidifies FDA authority to enforce FDCA regulation of against compounders of bioidentical hormone therapy.

In the United Kingdom, on the other hand, compounding is a regulated activity. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency regulates compounding performed under a Manufacturing Specials license and the General Pharmaceutical Council regulates compounding performed within a pharmacy. All testosterone prescribed in the United Kingdom is bioidentical, with its use supported by the National Health Service. There is also marketing authorisation for male testosterone products. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline 1.4.8 states: "consider testosterone supplementation for menopausal women with low sexual desire if HRT alone is not effective". The footnote adds: "at the time of publication (November 2015), testosterone did not have a United Kingdom marketing authorisation for this indication in women. Bioidentical progesterone is used in IVF treatment and for pregnant women who are at risk of premature labour."

Society and culture

Wyeth controversy

Wyeth, now a subsidiary of Pfizer, was a pharmaceutical company that marketed the HRT products Premarin (CEEs) and Prempro (CEEs + MPA). In 2009, litigation involving Wyeth resulted in the release of 1,500 documents that revealed practices concerning its promotion of these medications. The documents showed that Wyeth commissioned dozens of ghostwritten reviews and commentaries that were published in medical journals to promote unproven benefits of its HRT products, downplay their harms and risks, and cast competing therapies in a negative light. Starting in the mid-1990s and continuing for over a decade, Wyeth pursued an aggressive "publication plan" strategy to promote its HRT products through the use of ghostwritten publications. It worked mainly with DesignWrite, a medical writing firm. Between 1998 and 2005, Wyeth had 26 papers promoting its HRT products published in scientific journals. These favorable publications emphasized the benefits and downplayed the risks of its HRT products, especially the "misconception" of the association of its products with breast cancer. The publications defended unsupported cardiovascular "benefits" of its products, downplayed risks such as breast cancer, and promoted off-label and unproven uses like prevention of dementia, Parkinson's disease, vision problems, and wrinkles. In addition, Wyeth emphasized negative messages against the SERM raloxifene for osteoporosis, instructed writers to stress the fact that "alternative therapies have increased in usage since the WHI even though there is little evidence that they are effective or safe...", called into question the quality and therapeutic equivalence of approved generic CEE products, and made efforts to spread the notion that the unique risks of CEEs and MPA were a class effect of all forms of menopausal HRT: "Overall, these data indicate that the benefit/risk analysis that was reported in the Women's Health Initiative can be generalized to all postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy products." Following the publication of the WHI data in 2002, the stock prices for the pharmaceutical industry plummeted, and huge numbers of women stopped using HRT. The stocks of Wyeth, which supplied the Premarin and Prempro that were used in the WHI trials, decreased by more than 50%, and never fully recovered. Some of their articles in response promoted themes such as the following: "the WHI was flawed; the WHI was a controversial trial; the population studied in the WHI was inappropriate or was not representative of the general population of menopausal women; results of clinical trials should not guide treatment for individuals; observational studies are as good as or better than randomized clinical trials; animal studies can guide clinical decision-making; the risks associated with hormone therapy have been exaggerated; the benefits of hormone therapy have been or will be proven, and the recent studies are an aberration." Similar findings were observed in a 2010 analysis of 114 editorials, reviews, guidelines, and letters by five industry-paid authors. These publications promoted positive themes and challenged and criticized unfavorable trials such as the WHI and MWS. In 2009, Wyeth was acquired by Pfizer in a deal valued at US$68 billion. Pfizer, a company that produces Provera and Depo-Provera (MPA) and has also engaged in medical ghostwriting, continues to market Premarin and Prempro, which remain best-selling medications. According to Fugh-Berman (2010), "Today, despite definitive scientific data to the contrary, many gynecologists still believe that the benefits of RToutweigh the risks in asymptomatic women. This non-evidence–based perception may be the result of decades of carefully orchestrated corporate influence on medical literature." As many as 50% of physicians have expressed skepticism about large trials like the WHI and HERS in a 2011 survey. The positive perceptions of many physicians of HRT in spite of large trials showing risks that potentially outweigh any benefits may be due to the efforts of pharmaceutical companies like Wyeth, according to May and May (2012) and Fugh-Berman (2015).Popularity

The 1990s showed a dramatic decline in prescription rates, though more recently they have begun to rise again. Transdermal therapy, in part due to its lack of increase in venous thromboembolism, is now often the first choice for HRT in the United Kingdom. Conjugate equine estrogen, in distinction, has a potentially higher thrombosis risk and is now not commonly used in the UK, replaced by estradiol based compounds with lower thrombosis risk. Oral progestogen combinations such as medroxyprogesterone acetate have changed to dyhydrogesterone, due to a lack of association of the latter with venous clot.See also

* Androgen replacement therapy * Androgen deficiency *Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy or hormonal therapy is the use of hormones in medical treatment. Treatment with hormone antagonists may also be referred to as hormonal therapy or antihormone therapy. The most general classes of hormone therapy are hormonal therap ...

* Gender-affirming hormone therapy

Gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT), also called hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or transgender hormone therapy, is a form of hormone therapy in which sex hormones and other sex-hormonal agent, hormonal medications are administered to transg ...

* Feminizing hormone therapy

References

External links

Menopause treatment

Hormone Health Network, The Endocrine Society

Sexual Health and Menopause Online

The North American Menopause Society

Menopause

US Food and Drug Administration

British Menopause Society

{{Androgens and antiandrogens Endocrine procedures Life sciences industry Menopause Obstetrical and gynaecological procedures IARC Group 1 carcinogens pl:Hormonalna terapia zastępcza