Menachem HaMeiri on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Menachem ben Solomon HaMeiri (; , 1249–1315), commonly referred to as HaMeiri, the Meiri, or just Meiri, was a famous medieval Provençal

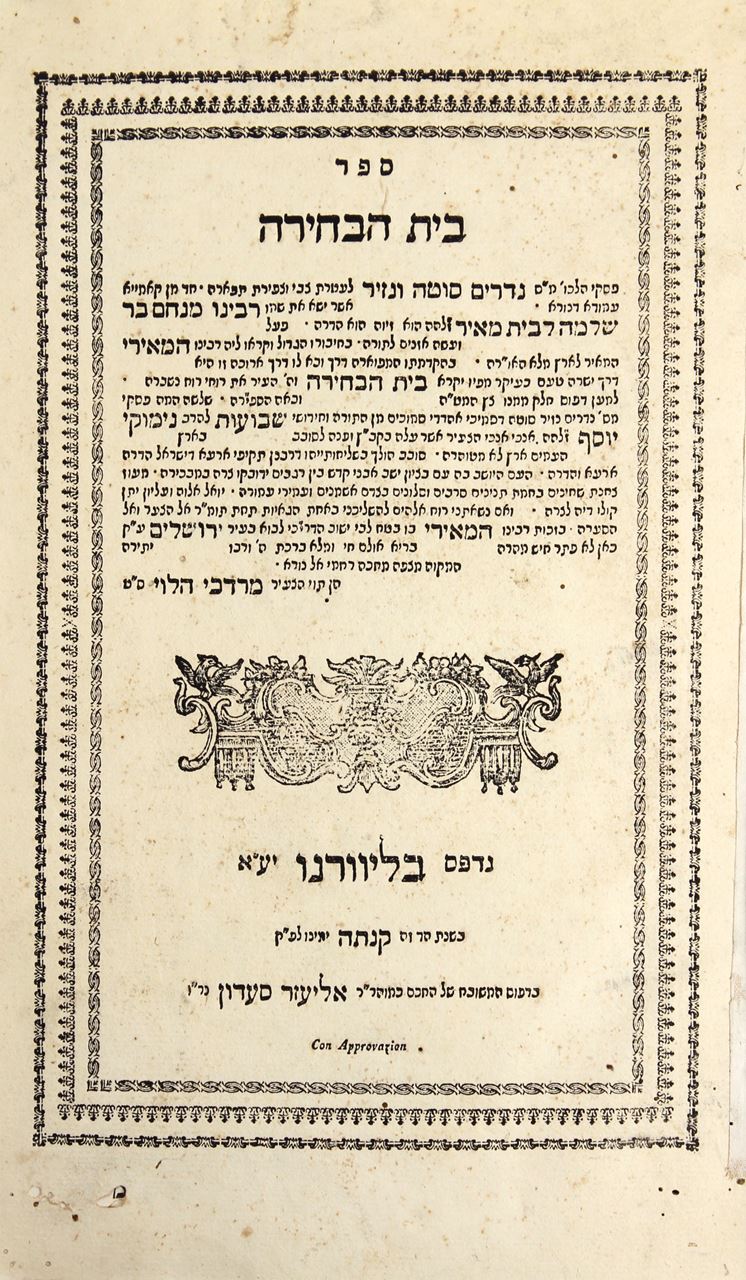

His commentary, the ''Beit HaBechirah'' (literally "The Chosen House," a play on an alternate name for the

His commentary, the ''Beit HaBechirah'' (literally "The Chosen House," a play on an alternate name for the

rabbi

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as ''semikha''—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of t ...

, and Talmudist

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

. Though most of his expansive commentary, spanning 35 tractates of the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

, was not publicly available until the turn of the 19th century, it has since gained widespread renown and acceptance among Talmudic scholars.

Biography

Menachem HaMeiri was born in 1249 inPerpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

, which then formed part of the Principality of Catalonia

The Principality of Catalonia (; ; ; ) was a Middle Ages, medieval and early modern state (polity), state in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. During most of its history it was in dynastic union with the Kingdom of Aragon, constituting together ...

. He was the student of Rabbi Reuven, the son of Chaim of Narbonne

Narbonne ( , , ; ; ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and was ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

.

In his writings, he refers to himself as HaMeiri ("the Meiri", or the Meirite; Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

: המאירי), presumably after one of his ancestors named Meir (Hebrew: מאיר), and that is how he is now known. Some have suggested that the reference is to Meir Detrancatleich, a student of the Raavad, who is mentioned in the Meiri's writings as one of his elders.

In his youth he was orphaned of his father, and his children were taken captive while he was still young, but no further details of these personal tragedies are known.

From the notorial certificates kept from Perpignan, it appears the Meiri made a living as a money lender, and his income was quite high.

The Meiri's principal teacher was Rabbi Reuven ben Chaim, and he kept a close correspondence and relationship with the Rashba, who was arguably the greatest Jewish rabbi of those times. Although the Meiri is known as one of the greatest scholars of his era, and despite his vast Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

knowledge and expertise, as testified to by many rabbis of his time and by his great expansive work ''Beit HaBechirah'', there is no evidence he ever held a rabbinic position, or even a teaching position in a Yeshiva

A yeshiva (; ; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are studied in parallel. The stu ...

(Jewish school for religious studies). This may have been in accordance with the teaching of the Rambam, who spoke harshly against turning the rabbinate solely into a means of livelihood.

''Beit HaBechirah''

His commentary, the ''Beit HaBechirah'' (literally "The Chosen House," a play on an alternate name for the

His commentary, the ''Beit HaBechirah'' (literally "The Chosen House," a play on an alternate name for the Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. Accord ...

, implying that the Meiri's work selects specific content from the Talmud, omitting the discursive elements), is one of the most monumental works written on the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

. This work is less a commentary and more of a digest of all of the comments in the Talmud, arranged in a manner similar to the Talmud—presenting first the ''mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

'' and then laying out the discussions that are raised concerning it. Haym Soloveitchik describes it as follows:

:Meiri is the only medieval Talmudist (rishon) whose works can be read almost independently of the Talmudic text, upon which it ostensibly comments. The Beit ha-Behirah is not a running commentary on the Talmud. Meiri, in quasi-Maimonidean fashion, intentionally omits the give and take of the sugya

A sugya is a self-contained passage of the Talmud that typically discusses a mishnah or other rabbinic statement, or offers an aggada, aggadic narrative.; see for overview.

While the sugya is a literary unit in the Jerusalem Talmud, the term is m ...

, he focuses, rather, on the final upshot of the discussion and presents the differing views of that upshot and conclusion. Also, he alone, and again intentionally, provides the reader with background information. His writings are the closest thing to a secondary source in the library of rishonim.

Unlike most ''rishonim'', he frequently quotes the Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

, including textual variants which are no longer extant in other sources.

''Beit HaBechirah'' cites many of the major ''Rishonim

''Rishonim'' (; ; sing. , ''Rishon'') were the leading rabbis and ''posek, poskim'' who lived approximately during the 11th to 15th centuries, in the era before the writing of the ''Shulchan Aruch'' (, "Set Table", a common printed code of Jewis ...

,'' referring to them not by name but rather by distinguished titles. Specifically:

* ''Gedolei HaRabbanim'' ("The Greatest of the Rabbis") – Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki (; ; ; 13 July 1105) was a French rabbi who authored comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible. He is commonly known by the List of rabbis known by acronyms, Rabbinic acronym Rashi ().

Born in Troyes, Rashi stud ...

* ''Gedolei HaMefarshim'' ("The Greatest of the Commentators") – Raavad (or ''Gedolei HaMagihim'', "The Greatest of the Annotaters", when quoted as disputing Rambam or Rif)

* ''Gedolei HaPoskim'' ("The Greatest of the ''Poskim''") – Isaac Alfasi

Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (1013–1103) (, ), also known as the Alfasi or by his Hebrew acronym, the Rif (Rabbi Isaac al-Fasi), was a Maghrebi Talmudist and posek (decider in matters of halakha, Jewish law). He is best known for his work of '' ...

* ''Gedolei HaMechabrim'' ("The Greatest of the Authors") – Rambam

* ''Geonei Sefarad'' ("The Brilliant of Spain") – Ri Migash (or, sometimes Rabbeinu Chananel)

* ''Chachmei HaTzarfatim'' ("The Wise of France") – Rashbam

Samuel ben Meir (Troyes, c. 1085 – c. 1158), after his death known as the "Rashbam", a Hebrew acronym for RAbbi SHmuel Ben Meir, was a leading French Tosafist and grandson of Shlomo Yitzhaki, "Rashi".

Biography

He was born in the vicinity of ...

(or, sometimes Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki (; ; ; 13 July 1105) was a French rabbi who authored comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible. He is commonly known by the List of rabbis known by acronyms, Rabbinic acronym Rashi ().

Born in Troyes, Rashi stud ...

)

* ''Achronei HaRabbonim'' ("The Later of the Rabbis") – Rabbeinu Tam

Jacob ben Meir (1100 – 9 June 1171 (4 Tammuz)), best known as Rabbeinu Tam (), was one of the most renowned Ashkenazi Jewish rabbis and leading French Tosafists, a leading '' halakhic'' authority in his generation, and a grandson of Rashi. K ...

* ''Gedolei HaDor'' ("The Greatest of the Generation") – Rashba

Historical influence

A complete copy of ''Beit HaBechira'' was preserved in the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma, rediscovered in 1920, and subsequently published. Snippets of ''Beit HaBechirah'' on one Tractate, Bava Kamma, were published long before the publication of the Parma manuscripts, included in the early collective work Shitah Mikubetzet. The common assumption has been that the large majority of the Meiri's works were not available to generations of halachists before 1920; as reflected in early 20th century authors such as the Chafetz Chaim, the Chazon Ish, andJoseph B. Soloveitchik

Joseph Ber Soloveitchik ( ''Yosef Dov ha-Levi Soloveychik''; February 27, 1903 – April 9, 1993) was a major American Orthodox rabbi, Talmudist, and modern Jewish philosopher. He was a scion of the Lithuanian Jewish Soloveitchik rabbinic ...

who write under the assumption that ''Beit HaBechira'' was newly discovered in their time, and further evidenced by the lack of mention of the Meiri and his opinions in the vast literature of halacha writings before the early 20th century.

''Beit HaBechira'' has had much less influence on subsequent halachic

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is based on biblical commandments ('' mitz ...

development than would have been expected given its stature. Several reasons have been given for this. Some modern ''poskim

In Jewish law, a ''posek'' ( , pl. ''poskim'', ) is a legal scholar who determines the application of ''halakha'', the Jewish religious laws derived from the written and Oral Torah, in cases of Jewish law where previous authorities are inconc ...

'' refuse to take its arguments into consideration, on the grounds that a work so long unknown has ceased to be part of the process of halachic development. One source held that the work was ignored due to its unusual length. Professor Haym Soloveitchik, though, suggested that the work was ignored due to its having the character of a secondary source – a genre which, he argues, was not appreciated among Torah learners until the late 20th century.

Other works

Menachem HaMeiri is also noted for having penned a famous work used to this very day by Jewishscribes

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The work of scribes can involve copying manuscripts and other texts as well as secretarial and ...

, namely, ''Kiryat Sefer'', a two-volume compendium outlining the rules governing the orthography

An orthography is a set of convention (norm), conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, punctuation, Word#Word boundaries, word boundaries, capitalization, hyphenation, and Emphasis (typography), emphasis.

Most national ...

that are to be adhered to when writing Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

scrolls.

He also wrote several minor works, including a commentary to '' Avot'' whose introduction includes a recording of the chain of tradition from Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

through the ''Tanaim

''Tannaim'' ( Amoraic Hebrew: תנאים "repeaters", "teachers", singular ''tanna'' , borrowed from Aramaic) were the rabbinic sages whose views are recorded in the Mishnah, from approximately 10–220 CE. The period of the Tannaim, also refe ...

.''

The Meiri also wrote a few commentaries ('' Chidushim'') on several tractates of the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

which differ to some extent from some of his positions in ''Beit HaBechira''. Most of these commentaries were lost, except for the commentary on Tractate Beitza. In addition, a commentary on Tractate Eruvin

An eruv is a religious-legal enclosure which permits carrying in certain areas on Shabbat.

Eruv may also refer to:

* '' Eruvin (Talmud)'', a tractate in ''Moed''

* Eruv tavshilin ("mixing of cooked dishes"), which permits cooking on a Friday H ...

was attributed to him, but this attribution was probably a mistake.

Halakhic positions

The Meiri's commentary is noted for its position on the status ofgentiles

''Gentile'' () is a word that today usually means someone who is not Jewish. Other Groups claiming affiliation with Israelites, groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, have historically used the term ''gentile'' to describe outsider ...

in Jewish law, asserting that discriminatory laws and statements found in the Talmud applied only to the idolatrous nations of old.

According to J. David Bleich, "the Christianity presented so favorably by Me’iri was not an orthodox Trinitarianism but a Christianity that espoused a theology formally branded heretical by the Church". However, Yaakov Elman argued that Bleich had no sources for this assertion.In the David Berger festschrift

In academia, a ''Festschrift'' (; plural, ''Festschriften'' ) is a book honoring a respected person, especially an academic, and presented during their lifetime. It generally takes the form of an edited volume, containing contributions from the h ...

on Jewish-Christian relations (edited by Elisheva Carlebach and J.J. Schacter)

See also

*Hachmei Provence

Hachmei Provence () refers to the hekhamim, "sages" or "rabbis," of Provence, now Occitania in France, which was a great center for Rabbinical Jewish scholarship in the times of the Tosafists. The singular form is ''hakham'', a Sephardic and Hach ...

References

Bibliography

* {{DEFAULTSORT:HaMeiri, Menachem 1249 births 1306 deaths Provençal rabbis 13th-century French writers French religious writers 13th-century Catalan rabbis People from Perpignan French male non-fiction writers Grammarians of Hebrew 14th-century Catalan rabbis