Medieval England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

England in the Middle Ages concerns the

England in the Middle Ages concerns the

In the 7th century, the Kingdom of Mercia rose to prominence under the leadership of King Penda.Fleming, p. 205. Mercia invaded neighbouring lands until it loosely controlled around 50 ''regiones'' covering much of England. Mercia and the remaining kingdoms, led by their warrior elites, continued to compete for territory throughout the 8th century. Massive earthworks, such as the defensive dyke built by

In the 7th century, the Kingdom of Mercia rose to prominence under the leadership of King Penda.Fleming, p. 205. Mercia invaded neighbouring lands until it loosely controlled around 50 ''regiones'' covering much of England. Mercia and the remaining kingdoms, led by their warrior elites, continued to compete for territory throughout the 8th century. Massive earthworks, such as the defensive dyke built by

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, took advantage of the English succession crisis to begin the

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, took advantage of the English succession crisis to begin the

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were

Within twenty years of the Norman conquest, the former Anglo-Saxon elite were replaced by a new class of Norman nobility, with around 8,000 Normans and French settling in England. The new

Within twenty years of the Norman conquest, the former Anglo-Saxon elite were replaced by a new class of Norman nobility, with around 8,000 Normans and French settling in England. The new

Medieval England was a

Medieval England was a

An English cultural identity first emerged from the interaction of the Germanic immigrants of the 5th and 6th centuries and the indigenous Romano-British inhabitants. Although early medieval chroniclers described the immigrants as Angles and Saxons, they came from a much wider area across Northern Europe, and represented a range of different ethnic groups. Over the 6th century, however, these different groups began to coalesce into stratified societies across England, roughly corresponding to the later Angle and Saxon kingdoms recorded by

An English cultural identity first emerged from the interaction of the Germanic immigrants of the 5th and 6th centuries and the indigenous Romano-British inhabitants. Although early medieval chroniclers described the immigrants as Angles and Saxons, they came from a much wider area across Northern Europe, and represented a range of different ethnic groups. Over the 6th century, however, these different groups began to coalesce into stratified societies across England, roughly corresponding to the later Angle and Saxon kingdoms recorded by

With the conversion of much of England in the 6th and 7th centuries, there was an explosion of local church building. English monasteries formed the main basis for the church, however, and were often sponsored by local rulers, taking various forms, including mixed communities headed by

With the conversion of much of England in the 6th and 7th centuries, there was an explosion of local church building. English monasteries formed the main basis for the church, however, and were often sponsored by local rulers, taking various forms, including mixed communities headed by

The Church had a close relationship with the English state throughout the Middle Ages. The bishops and major monastic leaders played an important part in national government, having key roles on the king's council. Bishops often oversaw towns and cities, managing local taxation and

The Church had a close relationship with the English state throughout the Middle Ages. The bishops and major monastic leaders played an important part in national government, having key roles on the king's council. Bishops often oversaw towns and cities, managing local taxation and

England had a diverse geography in the medieval period, from the Fenlands of

England had a diverse geography in the medieval period, from the Fenlands of

The English economy was fundamentally

The English economy was fundamentally

Technology and science in England advanced considerably during the Middle Ages, driven in part by the

Technology and science in England advanced considerably during the Middle Ages, driven in part by the

Warfare was endemic in early Anglo-Saxon England, and major conflicts still occurred approximately every generation in the later period. Groups of well-armed noblemen and their households formed the heart of these armies, supported by larger numbers of temporary troops levied from across the kingdom, called the

Warfare was endemic in early Anglo-Saxon England, and major conflicts still occurred approximately every generation in the later period. Groups of well-armed noblemen and their households formed the heart of these armies, supported by larger numbers of temporary troops levied from across the kingdom, called the

The first references to an English navy occur in 851, when chroniclers described Wessex ships defeating a Viking fleet. These early fleets were limited in size but grew in size in the 10th century, allowing the power of Wessex to be projected across the

The first references to an English navy occur in 851, when chroniclers described Wessex ships defeating a Viking fleet. These early fleets were limited in size but grew in size in the 10th century, allowing the power of Wessex to be projected across the

Many of the fortifications built by the Romans in England survived into the Middle Ages, including the walls surrounding their military forts and cities.Turner (1971), pp. 20–21; Creighton and Higham, pp. 56–58. These defences were often reused during the unstable post-Roman period. The Anglo-Saxon kings undertook significant planned urban expansion in the 8th and 9th centuries, creating ''burhs'', often protected with earth and wood ramparts. ''Burh'' walls sometimes utilised older Roman fortifications, both for practical reasons and to bolster their owners' reputations through the symbolism of former Roman power.

Although a small number of castles had been built in England during the 1050s, after the conquest the Normans began to build timber

Many of the fortifications built by the Romans in England survived into the Middle Ages, including the walls surrounding their military forts and cities.Turner (1971), pp. 20–21; Creighton and Higham, pp. 56–58. These defences were often reused during the unstable post-Roman period. The Anglo-Saxon kings undertook significant planned urban expansion in the 8th and 9th centuries, creating ''burhs'', often protected with earth and wood ramparts. ''Burh'' walls sometimes utilised older Roman fortifications, both for practical reasons and to bolster their owners' reputations through the symbolism of former Roman power.

Although a small number of castles had been built in England during the 1050s, after the conquest the Normans began to build timber

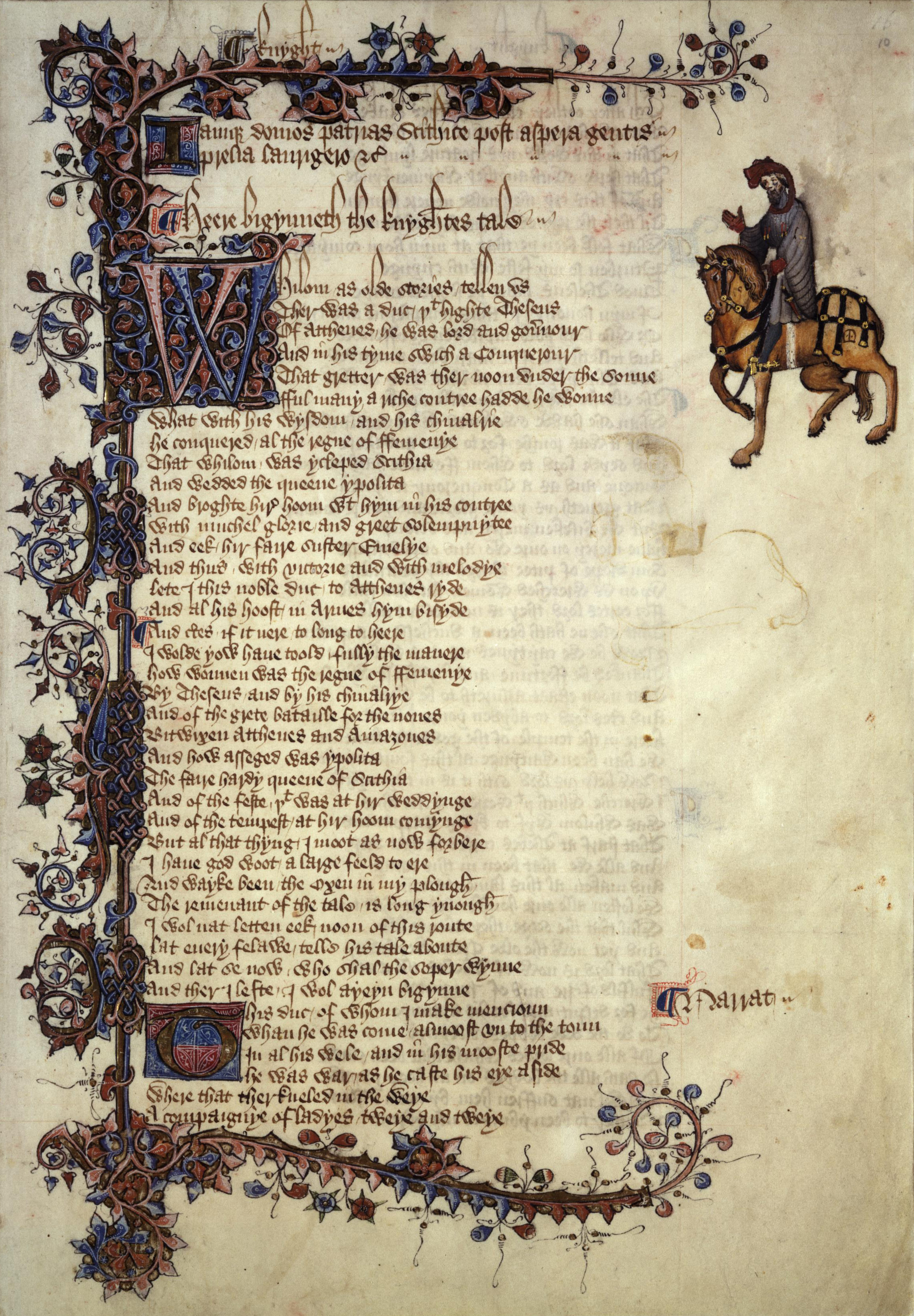

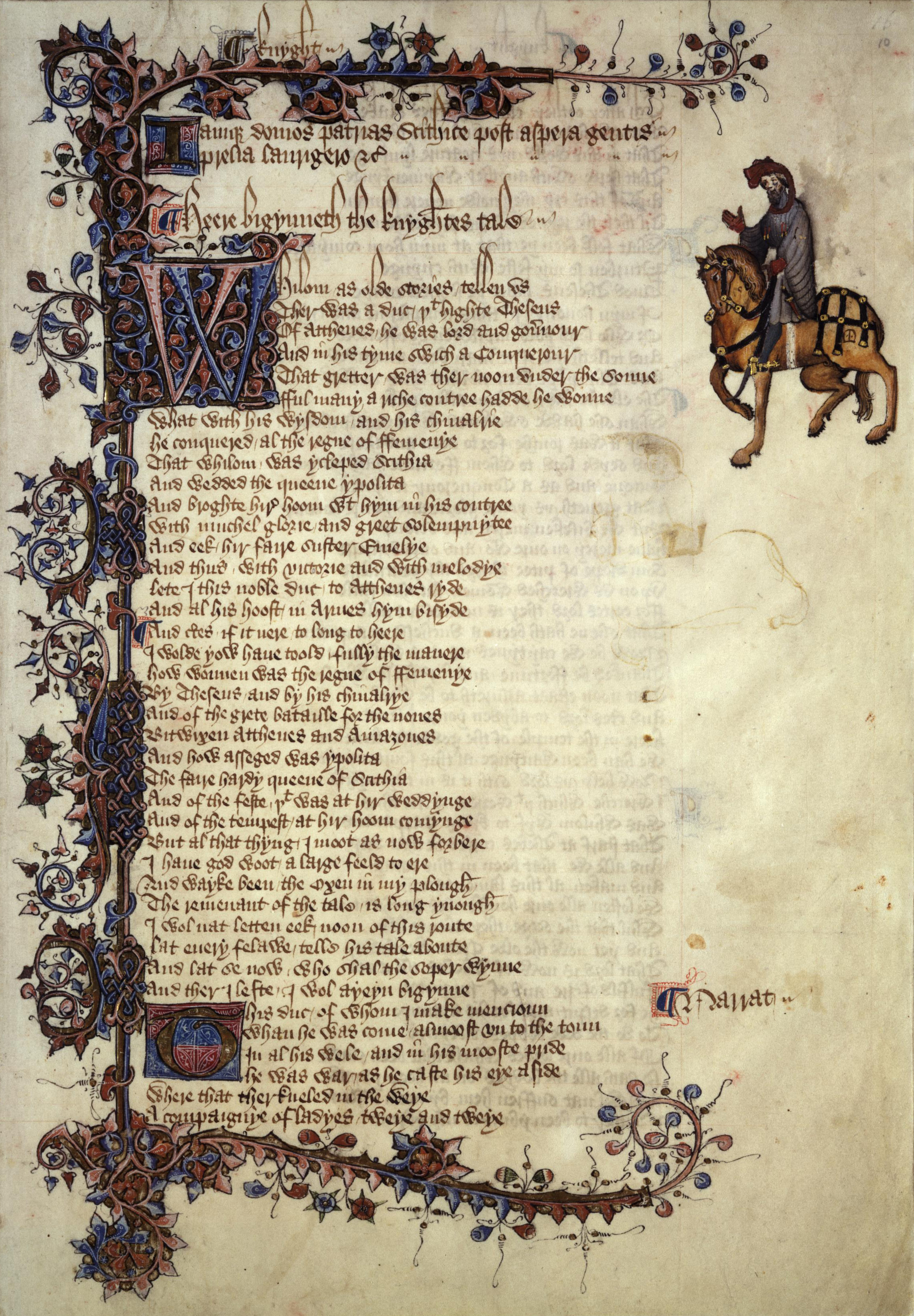

Medieval England produced art in the form of paintings, carvings, books, fabrics and many functional but beautiful objects.Kessler, pp. 14, 19. A wide range of materials was used, including gold, glass and ivory, the art usually drawing overt attention to the materials utilised in the designs. Anglo-Saxon artists created carved ivories,

Medieval England produced art in the form of paintings, carvings, books, fabrics and many functional but beautiful objects.Kessler, pp. 14, 19. A wide range of materials was used, including gold, glass and ivory, the art usually drawing overt attention to the materials utilised in the designs. Anglo-Saxon artists created carved ivories,

The Anglo-Saxons produced extensive poetry in

The Anglo-Saxons produced extensive poetry in

In the century after the collapse of the Romano-British economy, very few substantial buildings were constructed and many villas and towns were abandoned. New

In the century after the collapse of the Romano-British economy, very few substantial buildings were constructed and many villas and towns were abandoned. New

The first history of medieval England was written by Bede in the 8th century; many more accounts of contemporary and ancient history followed, usually termed

The first history of medieval England was written by Bede in the 8th century; many more accounts of contemporary and ancient history followed, usually termed

The period has also been used in a wide range of popular culture.

The period has also been used in a wide range of popular culture.

excerpt and text search

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

England in the Middle Ages concerns the

England in the Middle Ages concerns the history of England

The territory today known as England became inhabited more than 800,000 years ago, as the discovery of stone tools and footprints at Happisburgh in Norfolk have indicated.; "Earliest footprints outside Africa discovered in Norfolk" (2014). BB ...

during the medieval period

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

, from the end of the 5th century through to the start of the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

in 1485. When England emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, the economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

was in tatters and many of the towns abandoned. After several centuries of Germanic immigration, new identities and cultures began to emerge, developing into kingdoms that competed for power. A rich artistic culture flourished under the Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

, producing epic poems

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

such as ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poetry, Old English poem, an Epic poetry, epic in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translat ...

'' and sophisticated metalwork

Metalworking is the process of shaping and reshaping metals in order to create useful objects, parts, assemblies, and large scale structures. As a term, it covers a wide and diverse range of processes, skills, and tools for producing objects on e ...

. The Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity in the 7th century, and a network of monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which m ...

and convent

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

s were built across England. In the 8th and 9th centuries, England faced fierce Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

attacks, and the fighting lasted for many decades. Eventually, Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

was established as the most powerful kingdom and promoted the growth of an English identity. Despite repeated crises of succession and a Danish seizure of power at the start of the 11th century, it can also be argued that by the 1060s England was a powerful, centralised state with a strong military and successful economy.

The Norman invasion of England in 1066 led to the defeat and replacement of the Anglo-Saxon elite with Norman and French nobles and their supporters. William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

and his successors took over the existing state system, repressing local revolts and controlling the population through a network of castles. The new rulers introduced a feudal approach to governing England, eradicating the practice of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, but creating a much wider body of unfree labourers called serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

s. The position of women in society changed as laws regarding land and lordship shifted. England's population more than doubled during the 12th and 13th centuries, fueling an expansion of the towns, cities, and trade, helped by warmer temperatures across Northern Europe. A new wave of monasteries and friaries was established while ecclesiastical reforms led to tensions between successive kings and archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

s. Despite developments in England's governance and legal system

A legal system is a set of legal norms and institutions and processes by which those norms are applied, often within a particular jurisdiction or community. It may also be referred to as a legal order. The comparative study of legal systems is th ...

, infighting between the Anglo-Norman elite resulted in multiple civil wars and the loss of Normandy.

The 14th century in England saw the Great Famine and the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

, catastrophic events that killed around half of England's population, throwing the economy into chaos, and undermining the old political order. Social unrest followed, resulting in the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

of 1381, while the changes in the economy resulted in the emergence of a new class of gentry

Gentry (from Old French , from ) are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. ''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to Landed property, landed es ...

, and the nobility began to exercise power through a system termed bastard feudalism. Nearly 1,500 villages were deserted by their inhabitants and many men and women sought new opportunities in the towns and cities. New technologies were introduced, and England produced some of the great medieval philosophers and natural scientist

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

s. English kings in the 14th and 15th centuries laid claim to the French throne, resulting in the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

. At times England enjoyed huge military success, with the economy buoyed by profits from the international wool and cloth trade, but by 1450 the country was in crisis, facing military failure in France and an ongoing recession. More social unrest broke out, followed by the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses, known at the time and in following centuries as the Civil Wars, were a series of armed confrontations, machinations, battles and campaigns fought over control of the English throne from 1455 to 1487. The conflict was fo ...

, fought between rival factions of the English nobility. Henry VII's victory in 1485 over Richard III

Richard III (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485) was King of England from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the Plantagenet dynasty and its cadet branch the House of York. His defeat and death at the Battle of Boswor ...

at the Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field ( ) was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of House of Lancaster, Lancaster and House of York, York that extended across England in the latter half ...

conventionally marks the end of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

in England and the start of the Early Modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

.

Political history

Early Middle Ages (600–1066)

At the start of the Middle Ages, England was a part ofBritannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

, a former province of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. The local economy had once been dominated by imperial Roman spending on a large military establishment, which in turn helped to support a complex network of towns, roads, and villas. At the end of the 4th century, however, Roman forces had been largely withdrawn, and this economy collapsed. Germanic settlers began to arrive in increasing numbers during the 5th and 6th centuries, establishing small farms and settlements, and their language, Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

, swiftly spread as more settlers arrived and those of the previous inhabitants who had not moved west or to Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

switched from Common Brittonic

Common Brittonic (; ; ), also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, is a Celtic language historically spoken in Britain and Brittany from which evolved the later and modern Brittonic languages.

It is a form of Insular Cel ...

and British Latin

British Latin or British Vulgar Latin was the Vulgar Latin spoken in Great Britain in the Roman and sub-Roman periods. While Britain formed part of the Roman Empire, Latin became the principal language of the elite and in the urban areas of t ...

to the migrants' language. New political and social identities emerged, including an Anglian culture in the east of England and a Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

culture in the south, with local groups establishing ''regiones'', small polities ruled over by powerful families and individuals. By the 7th century, some rulers, including those of Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

, East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

, Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, and Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, had begun to term themselves kings, living in ''villae regales'', royal centres, and collecting tribute from the surrounding ''regiones''; these kingdoms are often referred to as the Heptarchy.

In the 7th century, the Kingdom of Mercia rose to prominence under the leadership of King Penda.Fleming, p. 205. Mercia invaded neighbouring lands until it loosely controlled around 50 ''regiones'' covering much of England. Mercia and the remaining kingdoms, led by their warrior elites, continued to compete for territory throughout the 8th century. Massive earthworks, such as the defensive dyke built by

In the 7th century, the Kingdom of Mercia rose to prominence under the leadership of King Penda.Fleming, p. 205. Mercia invaded neighbouring lands until it loosely controlled around 50 ''regiones'' covering much of England. Mercia and the remaining kingdoms, led by their warrior elites, continued to compete for territory throughout the 8th century. Massive earthworks, such as the defensive dyke built by Offa of Mercia

Offa ( 29 July 796 AD) was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death in 796. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of ...

, helped to defend key frontiers and towns. In 789, however, the first Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

n raids on England began; these Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

attacks grew in number and scale until in 865 the Danish ''micel here'' or Great Army, invaded England, captured York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

and defeated the kingdom of East Anglia. Mercia and Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

fell in 875 and 876, and Alfred of Wessex

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when A ...

was driven into internal exile in 878.

However, in the same year Alfred won a decisive victory against the Danes at the Battle of Edington

The Battle of Edington or Battle of Ethandun was fought in May 878 between the West Saxon army of King Alfred the Great and the Great Heathen Army led by the Danish warlord Guthrum. The battle took place near Edington, Wiltshire, Edington in ...

, and he exploited the fear of the Viking threat to raise large numbers of men and using a network of defended towns called ''burh

A burh () or burg was an Anglo-Saxon fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new constru ...

s'' to defend his territory and mobilise royal resources. Suppressing internal opposition to his rule, Alfred contained the invaders within a region known as the Danelaw

The Danelaw (, ; ; ) was the part of History of Anglo-Saxon England, England between the late ninth century and the Norman Conquest under Anglo-Saxon rule in which Danes (tribe), Danish laws applied. The Danelaw originated in the conquest and oc ...

. Under his son, Edward the Elder

Edward the Elder (870s?17 July 924) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 899 until his death in 924. He was the elder son of Alfred the Great and his wife Ealhswith. When Edward succeeded to the throne, he had to defeat a challenge from his cousi ...

, and his grandson, Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ; ; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Modern histori ...

, Wessex expanded further north into Mercia and the Danelaw, and by the 950s and the reigns of Eadred

Eadred (also Edred, – 23 November 955) was King of the English from 26 May 946 until his death in 955. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu of Kent, Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great. His elder b ...

and Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used masculine English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Edgar'' (composed of ''wikt:en:ead, ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''Gar (spear), gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the Late Midd ...

, York was finally permanently retaken from the Vikings. The West Saxon rulers were now kings of the ''Angelcynn'', that is of the whole English folk.

With the death of Edgar, however, the royal succession became problematic. Æthelred took power in 978 following the murder of his brother Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

, but England was then invaded by Sweyn Forkbeard

Sweyn Forkbeard ( ; ; 17 April 963 – 3 February 1014) was King of Denmark from 986 until his death, King of England for five weeks from December 1013 until his death, and King of Norway from 999/1000 until 1014. He was the father of King Ha ...

, the son of a Danish king.Fleming, pp. 314–315. Attempts to bribe Sweyn not to attack using danegeld

Danegeld (; "Danish tax", literally "Dane yield" or tribute) was a tax raised to pay tribute or Protection racket, protection money to the Viking raiders to save a land from being ravaged. It was called the ''geld'' or ''gafol'' in eleventh-c ...

payments failed, and he took the throne in 1013. Swein's son, Cnut

Cnut ( ; ; – 12 November 1035), also known as Canute and with the epithet the Great, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway from 1028 until his death in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut's rul ...

, liquidated many of the older English families following his seizure of power in 1016.Fleming, p. 315. Æthelred's son, Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was King of England from 1042 until his death in 1066. He was the last reigning monarch of the House of Wessex.

Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeede ...

, had survived in exile in Normandy and returned to claim the throne in 1042. Edward was childless, and the succession again became a concern. England became dominated by the Godwin family, who had taken advantage of the Danish killings to acquire huge wealth. When Edward died in 1066, Harold Godwinson claimed the throne, defeating his rival Norwegian claimant, Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' in the sagas, was List of Norwegian monarchs, King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. He unsuccessfully claimed the Monarchy of Denma ...

, at the battle of Stamford Bridge

The Battle of Stamford Bridge () took place at the village of Stamford Bridge, East Riding of Yorkshire, in England, on 25 September 1066, between an English army under Harold Godwinson, King Harold Godwinson and an invading Norwegian force l ...

.

High Middle Ages (1066–1272)

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, took advantage of the English succession crisis to begin the

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, took advantage of the English succession crisis to begin the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

. With an army of Norman followers and mercenaries, he defeated Harold at the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conquest of England. It took place appr ...

on 14 October 1066 and rapidly occupied the south of England. William used a network of castle

A castle is a type of fortification, fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by Military order (monastic society), military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private ...

s to control the major centres of power, granting extensive lands to his main Norman followers and co-opting or eliminating the former Anglo-Saxon elite. Major revolts followed, which William suppressed before intervening in the north-east of England, establishing Norman control of York and devastating the region. Some Norman lords used England as a launching point for attacks into South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

and North Wales

North Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdon ...

, spreading up the valleys to create new Marcher territories. By the time of William's death in 1087, England formed the largest part of an Anglo-Norman empire, ruled over by a network of nobles with landholdings across England, Normandy, and Wales. England's growing wealth was critical in allowing the Norman kings to project power across the region, including funding campaigns along the frontiers of Normandy.

Norman rule, however, proved unstable; successions to the throne were contested, leading to violent conflicts between the claimants and their noble supporters. William II inherited the throne but faced revolts attempting to replace him with his older brother Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, prais ...

or his cousin Stephen of Aumale

Stephen (Étienne) of Aumale (–1127) was Count of Aumale from before 1089 to 1127, and Lord of Holderness.

Life

Stephen I was the only son of Odo, Count of Champagne, and Adelaide of Normandy, Countess of Aumale, daughter of Robert I, Duk ...

. In 1100, William II died while hunting. Despite Robert's rival claims, his younger brother Henry I immediately seized power. War broke out, ending in Robert's defeat at Tinchebrai and his subsequent life imprisonment. Robert's son Clito remained free, however, and formed the focus for fresh revolts until his death in 1128. Henry's only legitimate son, William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

, died aboard the '' White Ship'' disaster of 1120, sparking a fresh succession crisis: Henry's nephew, Stephen of Blois, claimed the throne in 1135, but this was disputed by the Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda (10 September 1167), also known as Empress Maud, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter and heir of Henry I, king of England and ruler of Normandy, she went to ...

, Henry's daughter. Civil war broke out across England and Normandy, resulting in a long period of warfare later termed the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Duchy of Normandy, Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adel ...

. Matilda's son, Henry, finally agreed to a peace settlement at Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

and succeeded as king in 1154.

Henry II was the first of the Angevin rulers of England, so-called because he was also the Count of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by King Charles the Bald, Charles the Bald of West Francia in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the t ...

in Northern France. Henry had also acquired the huge duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine (, ; , ) was a historical fiefdom located in the western, central, and southern areas of present-day France, south of the river Loire. The full extent of the duchy, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries ...

by marriage, and England became a key part of a loose-knit assemblage of lands spread across Western Europe, later termed the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; ) was the collection of territories held by the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly all of present-day England, half of France, and parts of Ireland and Wal ...

. Henry reasserted royal authority and rebuilt the royal finances, intervening to claim power in Ireland and promoting the Anglo-Norman colonisation of the country. Henry strengthened England's borders with Wales and Scotland, and used the country's wealth to fund a long-running war with his rivals in France, but arrangements for his succession once again proved problematic. Several revolts broke out, led by Henry's children who were eager to acquire power and lands, sometimes backed by France, Scotland and the Welsh princes. After a final confrontation with Henry, his son Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199), known as Richard the Lionheart or Richard Cœur de Lion () because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior, was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ru ...

succeeded to the throne in 1189.

Richard spent his reign focused on protecting his possessions in France and fighting in the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

; his brother, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, inherited England in 1199 but lost Normandy and most of Aquitaine after several years of war with France. John fought successive, increasingly expensive, campaigns in a bid to regain these possessions. John's efforts to raise revenues, combined with his fractious relationships with many of the English barons, led to confrontation in 1215, an attempt to restore peace through the signing of ''Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

'', and finally the outbreak of the First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as English feudal barony, barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against John of England, K ...

. John died having fought the rebel barons and their French backers to a stalemate, and royal power was re-established by barons loyal to the young Henry III. England's power structures remained unstable and the outbreak of the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in Kingdom of England, England between the forces of barons led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of Henry III of England, King Hen ...

in 1264 resulted in the king's capture by Simon de Montfort. Henry's son, Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

, defeated the rebel factions between 1265 and 1267, restoring his father to power.

Late Middle Ages (1272–1485)

On becoming king, Edward I rebuilt the status of the monarchy, restoring and extending key castles that had fallen into disrepair. Uprisings by the princes of North Wales led to Edward mobilising a huge army, defeating the native Welsh and undertaking a programme of English colonisation and castle building across the region. Further wars were conducted inFlanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

and Aquitaine. Edward also fought campaigns in Scotland, but was unable to achieve strategic victory, and the costs created tensions that nearly led to civil war. Edward II inherited the war with Scotland and faced growing opposition to his rule as a result of his royal favourites and military failures. The Despenser War of 1321–22 was followed by instability and the subsequent overthrow, and possible murder, of Edward in 1327 at the hands of his French wife, Isabella, and a rebel baron, Roger Mortimer. Isabella and Mortimer's regime lasted only a few years before falling to a coup, led by Isabella's son Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, in 1330.

Like his grandfather, Edward III took steps to restore royal power, but during the 1340s the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

arrived in England. The losses from the epidemic, and the recurring plagues that followed it, significantly affected events in England for many years to come. Meanwhile, Edward, under pressure from France in Aquitaine, made a challenge for the French throne. Over the next century, English forces fought many campaigns in a long-running conflict that became known as the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

. Despite the challenges involved in raising the revenues to pay for the war, Edward's military successes brought an influx of plundered wealth to many parts of England and enabled substantial building work by the king. Many members of the English elite, including Edward's son the Black Prince, were heavily involved in campaigning in France and administering the new continental territories.

Edward's grandson, the young Richard II, faced political and economic problems, many resulting from the Black Death, including the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

that broke out across the south of England in 1381. Over the coming decades, Richard and groups of nobles vied for power and control of policy towards France until Henry of Bolingbroke seized the throne with the support of parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

in 1399. Ruling as Henry IV, he exercised power through a royal council and parliament, while attempting to enforce political and religious conformity. His son, Henry V, reinvigorated the war with France and came close to achieving strategic success shortly before his death in 1422. Henry VI became king at the age of only nine months and both the English political system and the military situation in France began to unravel.

A sequence of bloody civil wars, later termed the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses, known at the time and in following centuries as the Civil Wars, were a series of armed confrontations, machinations, battles and campaigns fought over control of the English throne from 1455 to 1487. The conflict was fo ...

, finally broke out in 1455; these wars were spurred on by an economic crisis and a widespread perception of poor government. Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in England ...

, leading a faction known as the Yorkists, removed Henry from power in 1461 but by 1469 fighting recommenced as Edward, Henry, and Edward's brother George, backed by leading nobles and powerful French supporters, vied for power. By 1471 Edward was triumphant and most of his rivals were dead.Hicks, p. 5. On his death, power passed to his brother Richard of Gloucester, who initially ruled on behalf of the young Edward V

Edward V (2 November 1470 – ) was King of England from 9 April to 25 June 1483. He succeeded his father, Edward IV, upon the latter's death. Edward V was never crowned, and his brief reign was dominated by the influence of his uncle and Lord ...

before seizing the throne himself as Richard III. The future Henry VII, aided by French and Scottish troops, returned to England and defeated Richard at the battle of Bosworth

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field ( ) was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 ...

in 1485, bringing an end to the majority of the fighting, although lesser rebellions against his Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor ( ) was an English and Welsh dynasty that held the throne of England from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd, a Welsh noble family, and Catherine of Valois. The Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of Eng ...

would continue for several years afterwards.

Government and society

Governance and social structures

Early Middle Ages (600–1066)

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were hierarchical

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an importan ...

societies, each based on ties of allegiance between powerful lords and their immediate followers. At the top of the social structure was the king, who stood above many of the normal processes of Anglo-Saxon life and whose household had special privileges and protection. Beneath the king were '' thegns'', nobles, the more powerful of which maintained their own courts and were termed '' ealdormen''. The relationship between kings and their nobles was bound up with military symbolism and the ritual exchange of weapons and armour. Freemen, called '' churls'', formed the next level of society, often holding land in their own right or controlling businesses in the towns.Whitelock, pp. 97–99. ''Geburs'', peasants who worked land belonging to a ''thegn'', formed a lower class still. The very lowest class were slaves, who could be bought and sold and who held only minimal rights.

The balance of power between these different groups changed over time. Early in the period, kings were elected by members of the late king's council, but primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn Legitimacy (family law), legitimate child to inheritance, inherit all or most of their parent's estate (law), estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some childre ...

rapidly became the norm for succession. The kings further bolstered their status by adopting Christian ceremonies and nomenclature, introducing ecclesiastical coronations during the 8th century and terming themselves "Christ's deputy" by the 11th century. Huge estates were initially built up by the king, bishops, monasteries and ''thegns'', but in the 9th and 10th centuries these were slowly broken up as a consequence of inheritance arrangements, marriage settlements and church purchases. In the 11th century, the royal position worsened further, as the ''ealdormen'' rapidly built up huge new estates, making them collectively much more powerful than the king—this contributed to the political instability of the final Anglo-Saxon years. As time went by, the position of the ''churls'' deteriorated, as their rights were slowly eroded and their duties to their lords increased.

The kingdom of Wessex, which eventually laid claim to England as a whole, evolved a centralised royal administration. One part of this was the king's council, the ''witenagemot

The witan () was the king's council in the Anglo-Saxon government of England from before the 7th century until the 11th century. It comprised important noblemen, including ealdormen, thegns, and bishops. Meetings of the witan were sometimes ...

'', comprising the senior clergy, ''ealdormen'', and some of the more important ''thegns''; the council met to advise the king on policy and legal issues. The royal household included officials, ''thegns'' and a secretariat of clergy which travelled with the king, conducting the affairs of government as it went. Under the Danish kings, a bodyguard of housecarls also accompanied the court. At a regional level, ''ealdormen'' played an important part in government, defence and taxation, and the post of sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland, the , which is common ...

emerged in the 10th century, administering local shire

Shire () is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries. It is generally synonymous with county (such as Cheshire and Worcestershire). British counties are among the oldes ...

s on behalf of an ealdorman. Anglo-Saxon mint

Mint or The Mint may refer to:

Plants

* Lamiaceae, the mint family

** ''Mentha'', the genus of plants commonly known as "mint"

Coins and collectibles

* Mint (facility), a facility for manufacturing coins

* Mint condition, a state of like-new ...

s were tightly controlled by the kings, providing a high-quality currency, and the whole country was taxed using a system called hidage.

The Anglo-Saxon kings built up a set of written laws, issued either as statutes or codes, but these laws were never written down in their entirety and were always supplemented by an extensive oral tradition of customary law. In the early part of the period local assemblies called moots were gathered to apply the laws to particular cases; in the 10th century these were replaced by hundred court

A hundred is an administrative division that is geographically part of a larger region. It was formerly used in England, Wales, some parts of the United States, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway, and in Cumberland County in the British Colony of ...

s, serving local areas, and shire moots dealing with larger regions of the kingdom. Many churchmen and ''thegns'' were also given permission by the king to hold their own local courts. The legal system depended on a system of oath

Traditionally, an oath (from Old English, Anglo-Saxon ', also a plight) is a utterance, statement of fact or a promise taken by a Sacred, sacrality as a sign of Truth, verity. A common legal substitute for those who object to making sacred oaths ...

s in which the value of different individuals swearing on behalf of the plaintiff or defendant varied according to their social status – the word of a companion of the king, for example, was worth twelve times that of a ''churl''. If fines were imposed, their size similarly varied accord to the oath-value of the individual. The Anglo-Saxon authorities struggled to deal with the bloodfeuds between families that emerged following violent killings, attempting to use a system of ''weregild

Weregild (also spelled wergild, wergeld (in archaic/historical usage of English), weregeld, etc.), also known as man price ( blood money), was a precept in some historical legal codes whereby a monetary value was established for a person's life, ...

'', a payment of blood money, as a way of providing an alternative to long-running vendettas.

High Middle Ages (1066–1272)

Within twenty years of the Norman conquest, the former Anglo-Saxon elite were replaced by a new class of Norman nobility, with around 8,000 Normans and French settling in England. The new

Within twenty years of the Norman conquest, the former Anglo-Saxon elite were replaced by a new class of Norman nobility, with around 8,000 Normans and French settling in England. The new earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the Peerages in the United Kingdom, peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ...

s (successors to the ealdermen), sheriffs and church seniors were all drawn from their ranks. In many areas of society there was continuity, as the Normans adopted many of the Anglo-Saxon governmental institutions, including the tax system, mints and the centralisation of law-making and some judicial matters; initially sheriffs and the hundred courts continued to function as before. The existing tax liabilities were captured in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

, produced in 1086.

Changes in other areas soon began to be felt. The method of government after the conquest can be described as a feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structuring socie ...

, in that the new nobles held their lands on behalf of the king; in return for promising to provide military support and taking an oath of allegiance, called homage, they were granted lands termed a fief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

or an honour

Honour (Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself ...

. Major nobles in turn granted lands to smaller landowners in return for homage and further military support, and eventually the peasantry held land in return for local labour services, creating a web of loyalties and resources enforced in part by new honorial courts. This system had been used in Normandy and concentrated more power in the king and the upper elite than the former Anglo-Saxon system of government. The practice of slavery declined in the years after the conquest, as the Normans considered the practice backward and contrary to the teachings of the church. The more prosperous peasants, however, lost influence and power as the Normans made holding land more dependent on providing labour services to the local lord. They sank down the economic hierarchy, swelling the numbers of unfree villein

A villein is a class of serfdom, serf tied to the land under the feudal system. As part of the contract with the lord of the manor, they were expected to spend some of their time working on the lord's fields in return for land. Villeins existe ...

s or serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

, forbidden to leave their manor or seek alternative employment.Douglas, p. 312.

At the centre of power, the kings employed a succession of clergy as chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

s, responsible for running the royal chancery, while the '' familia regis'', the military household, emerged to act as a bodyguard and military staff. England's bishops continued to form an important part in local administration, alongside the nobility. Henry I and Henry II both implemented significant legal reforms, extending and widening the scope of centralised, royal law; by the 1180s, the basis for the future English common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

had largely been established, with a standing law court in Westminster—an early Common Bench

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century af ...

—and travelling judges conducting eyres around the country. King John extended the royal role in delivering justice, and the extent of appropriate royal intervention was one of the issues addressed in the ''Magna Carta'' of 1215. The emerging legal system reinvigorated the institution of serfdom in the 13th century by drawing an increasingly sharp distinction between freemen and villeins.

Many tensions existed within the system of government. Royal landownings and wealth stretched across England, and placed the king in a privileged position above even the most powerful of the noble elite. Successive kings, though, still needed more resources to pay for military campaigns, conduct building programmes or to reward their followers, and this meant exercising their feudal rights to interfere in the land-holdings of nobles. This was contentious and a frequent issue of complaint, as there was a growing belief that land should be held by hereditary right, not through the favour of the king. Property and wealth became increasingly focused in the hands of a subset of the nobility, the great magnates, at the expense of the wider baronage, encouraging the breakdown of some aspects of local feudalism. As time went by, the Norman nobility intermarried with many of the great Anglo-Saxon families, and the links with the Duchy began to weaken. By the late 12th century, mobilising the English barons to fight on the continent was proving difficult, and John's attempts to do so ended in civil war. Civil strife re-emerged under Henry III, with the rebel barons in 1258–59 demanding widespread reforms, and an early version of Parliament was summoned in 1265 to represent the rebel interests.

Late Middle Ages (1272–1485)

On becoming king in 1272, Edward I reestablished royal power, overhauling the royal finances and appealing to the broader English elite by using Parliament to authorise the raising of new taxes and to hear petitions concerning abuses of local governance. This political balance collapsed under Edward II and savage civil wars broke out during the 1320s. Edward III restored order once more with the help of a majority of the nobility, exercising power through theexchequer

In the Civil Service (United Kingdom), civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty's Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''Transaction account, current account'' (i.e., mon ...

, the common bench and the royal household. This government was better organised and on a larger scale than ever before, and by the 14th century the king's formerly peripatetic chancery had to take up permanent residence in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

. Edward used Parliament even more than his predecessors to handle general administration, to legislate and to raise the necessary taxes to pay for the wars in France. The royal lands—and incomes from them—had diminished over the years, and increasingly frequent taxation was required to support royal initiatives. Edward held elaborate chivalric events in an effort to unite his supporters around the symbols of knighthood. The ideal of chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

continued to develop throughout the 14th century, reflected in the growth of knightly orders (including the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

), grand tournament

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concen ...

s and round table

The Round Table (; ; ; ) is King Arthur's famed table (furniture), table in the Arthurian legend, around which he and his knights congregate. As its name suggests, it has no head, implying that everyone who sits there has equal status, unlike co ...

events.

Society and government in England in the early 14th century were challenged by the Great Famine and the Black Death. The economic and demographic crisis created a sudden surplus of land, undermining the ability of landowners to exert their feudal rights and causing a collapse in incomes from rented lands. Wages soared, as employers competed for a scarce workforce. Statute of Labourers 1351

The Statute of Labourers ( 25 Edw. 3. Stat. 2) was an act of the Parliament of England under King Edward III in 1351 in response to a labour shortage, which aimed at regulating the labour force by prohibiting requesting or offering a wage hi ...

was introduced to limit wages and to prevent the consumption of luxury goods by the lower classes, with prosecutions coming to take up most of the legal system's energy and time. A poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

was introduced in 1377 that spread the costs of the war in France more widely across the whole population. The tensions spilled over into violence in the summer of 1381 in the form of the Peasants' Revolt; a violent retribution followed, with as many as 7,000 alleged rebels executed. A new class of gentry

Gentry (from Old French , from ) are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. ''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to Landed property, landed es ...

emerged as a result of these changes, renting land from the major nobility to farm out at a profit. The legal system continued to expand during the 14th century, dealing with an ever-wider set of complex problems.

By the time that Richard II was deposed in 1399, the power of the major noble magnates had grown considerably; powerful rulers such as Henry IV would contain them, but during the minority of Henry VI they controlled the country. The magnates depended upon their income from rent and trade to allow them to maintain groups of paid, armed retainers, often sporting controversial livery, and buy support amongst the wider gentry; this system has been dubbed bastard feudalism. Their influence was exerted both through the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

at Parliament and through the king's council. The gentry and wealthier townsmen exercised increasing influence through the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

, opposing raising taxes to pay for the French wars. By the 1430s and 1440s the English government was in major financial difficulties, leading to the crisis of 1450 and a popular revolt under the leadership of Jack Cade. Law and order deteriorated, and the crown was unable to intervene in the factional fighting between different nobles and their followers. The resulting Wars of the Roses saw a savage escalation of violence between the noble leaderships of both sides: captured enemies were executed and family lands attainted. By the time that Henry VII took the throne in 1485, England's governmental and social structures had been substantially weakened, with whole noble lines extinguished.

Women in society

Medieval England was a

Medieval England was a patriarchal society

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of authority are primarily held by men. The term ''patriarchy'' is used both in anthropology to describe a family or clan controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males, and in fem ...

and the lives of women were heavily influenced by contemporary beliefs about gender and authority. However, the position of women varied considerably according to various factors, including their social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

; whether they were unmarried, married, widowed or remarried; and in which part of the country they lived. Significant gender inequalities persisted throughout the period, as women typically had more limited life-choices, access to employment and trade, and legal rights than men.

In Anglo-Saxon society, noblewomen enjoyed considerable rights and status, although the society was still firmly patriarchal. Some exercised power as abbesses, exerting widespread influence across the early English Church, although their wealth and authority diminished with the monastic reforms of the 9th century. Anglo-Saxon queens began to hold lands in their own right in the 10th century and their households contributed to the running of the kingdom. Although women could not lead military forces, in the absence of their husbands some noblewomen led the defence of manors and towns. Most Anglo-Saxon women, however, worked on the land as part of the agricultural community, or as brewer

Brewing is the production of beer by steeping a starch source (commonly cereal grains, the most popular of which is barley) in water and fermenting the resulting sweet liquid with yeast. It may be done in a brewery by a commercial brewer, ...

s or baker

A baker is a tradesperson who baking, bakes and sometimes Sales, sells breads and other products made of flour by using an oven or other concentrated heat source. The place where a baker works is called a bakery.

History

Ancient histo ...

s.

After the Norman invasion, the position of women in society changed. The rights and roles of women became more sharply defined, in part as a result of the development of the feudal system and the expansion of the English legal system; some women benefited from this, while others lost out. The rights of widows were formally laid down in law by the end of the 12th century, clarifying the right of free women to own property, but this did not necessarily prevent women from being forcibly remarried against their wishes. The growth of governmental institutions under a succession of bishops reduced the role of queens and their households in formal government. Married or widowed noblewomen remained significant cultural and religious patrons and played an important part in political and military events, even if chroniclers were uncertain if this was appropriate behaviour. As in earlier centuries, most women worked in agriculture, but here roles became more clearly gendered, with ploughing and managing the fields defined as men's work, for example, and dairy production becoming dominated by women.

The years after the Black Death left many women widows; in the wider economy labour was in short supply and land was suddenly readily available. In rural areas peasant women could enjoy a better standard of living than ever before, but the amount of work being done by women may have increased. Many other women travelled to the towns and cities, to the point where they outnumbered men in some settlements. There they worked with their husbands, or in a limited number of occupations, including spinning, making clothes, victualling and as servants. Some women became full-time ale brewers, until they were pushed out of business by the male-dominated beer

Beer is an alcoholic beverage produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches from cereal grain—most commonly malted barley, although wheat, maize (corn), rice, and oats are also used. The grain is mashed to convert starch in the ...

industry in the 15th century. Higher status jobs and apprenticeships, however, remained closed to women. As in earlier times, noblewomen exercised power on their estates in their husbands' absence and again, if necessary, defended them in sieges and skirmishes. Wealthy widows who could successfully claim their rightful share of their late husband's property could live as powerful members of the community in their own right.

Identity

Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

in the 8th century. By the 9th century, the term the ''Angelcynn'' was being officially used to refer to a single English people, and promoted for propaganda purposes by chroniclers and kings to inspire resistance to the Danish invasions.Carpenter, p. 3.

The Normans and French who arrived after the conquest saw themselves as different from the English. They had close family and economic links to the Duchy of Normandy, spoke Norman French

Norman or Norman French (, , Guernésiais: , Jèrriais: ) is a '' langue d'oïl'' spoken in the historical and cultural region of Normandy.

The name "Norman French" is sometimes also used to describe the administrative languages of '' Angl ...

and had their own distinctive culture. For many years, to be English was to be associated with military failure and serfdom. During the 12th century, the divisions between the English and Normans began to dissolve as a result of intermarriage and cohabitation. By the end of the 12th century, and possibly as early as the 1150, contemporary commentators believed the two peoples to be blending, and the loss of the Duchy in 1204 reinforced this trend. The resulting society still prized wider French cultural values, however, and French remained the language of the court, business and international affairs, even if Parisians mocked the English for their poor pronunciation. By the 14th century, however, French was increasingly having to be formally taught, rather than being learnt naturally in the home, although the aristocracy would typically spend many years of their lives in France and remained entirely comfortable working in French.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, the English began to consider themselves superior to the Welsh, Scots and Bretons

The Bretons (; or , ) are an ethnic group native to Brittany, north-western France. Originally, the demonym designated groups of Common Brittonic, Brittonic speakers who emigrated from Dumnonia, southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwal ...

. The English perceived themselves as civilised, economically prosperous and properly Christian, while the Celtic fringe was considered lazy, barbarous and backward. Following the invasion of Ireland in the late 12th century, similar feelings were expressed about the Irish, with the distinctions clarified and reinforced in 14th-century English legislation. The English also felt strongly about the foreign traders who lived in the special enclaves in London in the Late Middle Ages; the position of the Jews is described below, but Italian and Baltic traders were also regarded as aliens and were frequently the targets of violence during economic downturns.Hicks, pp. 52–53. Even within England, different identities abounded, each with their own sense of status and importance. Regional identities could be important – men and women from Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

, for example, had a clear identity within English society, and professional groups with a distinct identity, such as lawyers, engaged in open fighting with others in cities such as London.

Jews

The Jewish community played an important role in England throughout much of the period. The first Jews arrived in England in the aftermath of the Norman invasion, when William the Conqueror brought over wealthy members of theRouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

community in Normandy to settle in London. The Jewish community expanded out across England and provided essential money-lending and banking services that were otherwise banned by the usury laws. During the 12th century, the Jewish financial community grew richer still, operating under royal protection and providing the king with a source of ready credit. All major towns had Jewish centres, and even the smaller towns saw visits by travelling Jewish merchants. Towards the end of Henry II's reign, however, the king ceased to borrow from the Jewish community and instead turned to extracting money from them through arbitrary taxation and fines. The Jews became vilified and accusations were made that they conducted ritual child murder, encouraging the pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s carried out against Jewish communities in the reign of Richard I. After an initially peaceful start to John's reign, the king again began to extort money from the Jewish community and, with the breakdown in order in 1215, the Jews were subject to fresh attacks. Henry III restored some protection and Jewish money-lending began to recover. Despite this, the Jewish community became increasingly impoverished and was finally expelled from England in 1290 by Edward I, being replaced by foreign merchants.

Religion

Rise of Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

had been the official imperial religion of the Roman Empire, and the first churches were built in England in the second half of the 4th century, overseen by a hierarchy of bishops and priests.Fleming, pp. 121, 126. Many existing pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...