May Howard Jackson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

May Howard Jackson (September 7, 1877 – July 12, 1931) was an African American sculptor and artist. Active in the

After Jackson's move to Washington, "she had expected to continue her studies at the art school connected with the

After Jackson's move to Washington, "she had expected to continue her studies at the art school connected with the

Artists like Jackson responded to the lack of gallery support by pressing alternative public spaces into service, such as the "War Service and Recreation Center" of the Washington Y.M.C.A., where, in May 1919, a solo "exhibition of 25 sculptures of May Howard Johnson" was held.

The M Street High School moved to new buildings and was renamed Dunbar School in 1916 for the noted African-American intellectual and poet,

Artists like Jackson responded to the lack of gallery support by pressing alternative public spaces into service, such as the "War Service and Recreation Center" of the Washington Y.M.C.A., where, in May 1919, a solo "exhibition of 25 sculptures of May Howard Johnson" was held.

The M Street High School moved to new buildings and was renamed Dunbar School in 1916 for the noted African-American intellectual and poet,

New Negro Movement

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African Americans, African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s a ...

and prominent in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

's African American intellectual circle in the period 1910–30, she was known as "one of the first black sculptors to...deliberately use America's racial problems" as the theme of her art. Her dignified portrayals of "mulatto

( , ) is a Race (human categorization), racial classification that refers to people of mixed Sub-Saharan African, African and Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry only. When speaking or writing about a singular woman in English, the ...

" individuals as well as her own struggles with her multiracial

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races (human categorization), races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicity, ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used ...

identity continue to call for the interpretation and assessment of her work.

Early life

Education

May Howard was born to a middle class couple, Floarda Howard and Sallie (Durham) Howard, in Philadelphia on September 7, 1877. She attended J. Liberty Tadd'sArt School

An art school is an educational institution with a primary focus on practice and related theory in the visual arts and design. This includes fine art – especially illustration, painting, contemporary art, sculpture, and graphic design. T ...

in Philadelphia, where she was trained with "new methods in education." Tadd, the school's founder, was an educational innovator who "emphasized the importance of visual arts training" to strengthen the brain, advocating an ambidextrous teaching model and six years of early-school art education. At Tadd's school May Howard studied "drawing, designing, free-hand drawing, working designs in monochrome, modeling, wood carving, and the use of tools".

She continued her art training, with the support of a full scholarship, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) is a museum and private art school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1805, it is the longest continuously operating art museum and art school in the United States.

The academy's museum ...

(1895), as the first African American woman to attend PAFA, studying under various known artists including the renowned American Impressionist

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

William Merritt Chase

William Merritt Chase (November 1, 1849October 25, 1916) was an American painter, known as an exponent of Impressionism and as a teacher. He is also responsible for establishing the Chase School, which later became the Parsons School of Design.

...

, Paris-trained academic sculptor Charles Grafly

Charles Allan Grafly, Jr. (December 3, 1862 – May 5, 1929) was an American sculptor, and teacher. Instructor of Sculpture at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for 37 years, his students included Paul Manship, Albin Polasek, and Walker H ...

, and John J. Boyle (who had been a student of former PAFA faculty member Thomas Eakins

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (; July 25, 1844 – June 25, 1916) was an American Realism (visual arts), realist painter, photographer, sculptor, and fine arts educator. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the most important American artist ...

). Her surviving work from this period expresses the Beaux-Arts aesthetic that emphasized naturalism and dynamic treatment of surface and form.

Meta Warrick Fuller, Jackson's contemporary at Tadd's and PAFA (like Howard, b. 1877), offered Jackson the opportunity to accompany her and study abroad in France during this time (Fuller herself had enrolled in classes at the École des Beaux Arts

École or Ecole may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* Éco ...

). Jackson declined. She would later declare she thought it unnecessary to travel to Europe to further her art.

After four years of study at PAFA, Howard met and "married well" a mathematics teacher and future high school principal, William Sherman Jackson.

Washington, D.C. and the M Street High School

By 1902, May and William were living in Washington D.C., where William was teaching at theM Street High School

M Street High School, also known as Dunbar High School, is a historic former school building located in the Northwest Quadrant of Washington, D.C. It has been listed on the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites since 1978 and it was li ...

, the first public high school for African Americans in the United States, and, at that time, the premier preparatory academy in the nation for students of color. The faculty at M Street High School were "arguably superior to the white public schools, whose teachers typically were graduates of normal schools and teacher colleges." Many M Street teachers (William included) were the pioneering alumni of American's top academic institutions, unable, post graduation, to find employment at college institutions.

Because of these circumstances, in the first decade of the new century, the M Street High School found itself center stage for the nation's debate about the future of Black education. On the one side, Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, and orator. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the primary leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite#United S ...

, former child slave, urged Black Americans to recognize that "the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands... No race can prosper until it learns that there is as much dignity in the tilling of a field as in the writing of a poem," and worked for access to the vocational training that could elevate and secure colored peoples' place in the American economy. On the other side was Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois, the Massachusetts born, Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

educated leader of the New Negro Movement

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African Americans, African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s a ...

and a central figure in the 1908 formation of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

. Du Bois's recently published book of essays, ''The Souls of Black Folk'' (1903) had catalyzed the thinking of many African Americans, countering what Du Bois saw as Mr. Washington's "cult of submission" with the contention that Black Americans must enjoy the "right to vote," "civic equality," and the education of their youth "according to ability."

For the M Street School, in competition with the nearby colored vocational school for the D.C. school department's support and resources, and straining to build the nation's first college preparatory program for colored students, Du Bois's final point here would prove a particularly contentious rallying call. Washington, approved to speak at the 1904 M Street Graduation, recommended that Blacks focus on gaining "common school and industrial training," first and foremost. Principal Anna J. Cooper countered this by inviting Du Bois to deliver a speech at the M Street School, in the winter of 1903, opposing vocational education as an acceptable standard for Black Americans. The DC director of schools accused Dr. Cooper of insubordination and disloyalty.

Cooper's tenure as Principal survived the accusations, but in 1906, she ceded her position to Jackson's husband William. May came on as faculty to teach Latin. William would step back from his role as Principal in 1909, but the couple's central role in maintaining the M Street High School's reputation for academic excellence through a difficult period left them with an invaluable social credential in Washington's Black community and beyond.

Career

After Jackson's move to Washington, "she had expected to continue her studies at the art school connected with the

After Jackson's move to Washington, "she had expected to continue her studies at the art school connected with the Corcoran Art Gallery

The Corcoran Gallery of Art is a former art museum in Washington, D.C., that is now the location of the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, a part of the George Washington University.

Founded in 1869 by philanthropist William Wilson Corcoran ...

but was refused admission because of her color," a rejection that, for a time, discouraged her from pursuing public work in her field. She would later maintain that "It was chiefly through Dr. Du Bois's influence and urging that she again took up her work with the determination to make the most of her gifts for the encouragement it would be to her people."

Du Bois not only personally encouraged her, but used her images to illustrate ''The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly M ...

'', his newly established journal and, from 1910, the official magazine of the NAACP.

With this support, Jackson became "the first to break away from academic cosmopolitanism to frank and deliberate racialism" in her artwork. This determination is evident from her best known surviving pieces: the dignified portrait busts she created of the period's black leaders "decent portraits of decent men", and her intimate family groupings of mothers—mixed race themselves—caressing children—their own children—of mixed racial heritage. For the next two decades, these works would be the headliners of her exhibited work.

Jackson arranged for Dr. Du Bois to sit for her in 1907. Although the in-person sessions were discontinued before her portrait bust was finished, Du Bois arranged for photographs to be sent from New York so she could bring the piece to successful completion. Last, and perhaps most helpfully, Du Bois published news of her exhibitions and work in the pages of The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly M ...

, through to 1931 and the artist's early death.

Public exhibitions

Washington gallery scene

In 1912, her portrait bust of Du Bois, among other works, was exhibited at the Veerhoff Gallery in Washington. She received a positive review from ''The Washington Star

''The Washington Star'', previously known as the ''Washington Star-News'' and the ''Washington'' ''Evening Star'', was a daily afternoon newspaper published in Washington, D.C., between 1852 and 1981. The Sunday edition was known as the ''Sunday ...

'' commending the work's structure: "the expression is vital and good, the turn of surface, the intimation of mobility are well rendered." The ''Star'', reviewing her bust of ''Assistant Attorney General WIlliam H. Lewis,'' later that same fall, took the compliment further, "A portrait to deserve the name must be more than a likeness; it must interpret character; it must have personality. Of this bust as much can truly be said."

Exhibiting a broader collection of sculptures at the Veerhoff in 1916, her ''Star'' review was again effusive: Jackson's "work has always shown promise, but these pieces now on exhibit indicate exceptional gift, for they are not merely well modeled, but individual and significant".

As a woman defined by the color of her skin, finding public venues to display her work was a constant challenge. "It is not at all customary for Washington art stores to exhibit the works of colored artists," a contemporary reviewer observed, "particularly if the subjects are too colored, and the fact that Mrs. Jackson's work has been displayed, is evidence of her talent."

In 1917, Jackson exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery

The Corcoran Gallery of Art is a former art museum in Washington, D.C., that is now the location of the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, a part of the George Washington University.

Founded in 1869 by philanthropist William Wilson Corcoran ...

in Washington, from whose art school, she had been rejected, on a racial basis, on her arrival in DC fifteen years before. The event was written up in a brief newspaper piece ("First Recognition for the Race") that ran in papers across the United States as widespread as Omaha and Salt Lake City. "What is said to be the first recognition of colored talent by that institution is the exhibition in Corcoran Art Gallery, at Washington, D.C. of a child's head modeled by Mrs. May Howard Jackson."

And then—the National Academy of Design, New York (1919))

Segregated exhibitions

Artists like Jackson responded to the lack of gallery support by pressing alternative public spaces into service, such as the "War Service and Recreation Center" of the Washington Y.M.C.A., where, in May 1919, a solo "exhibition of 25 sculptures of May Howard Johnson" was held.

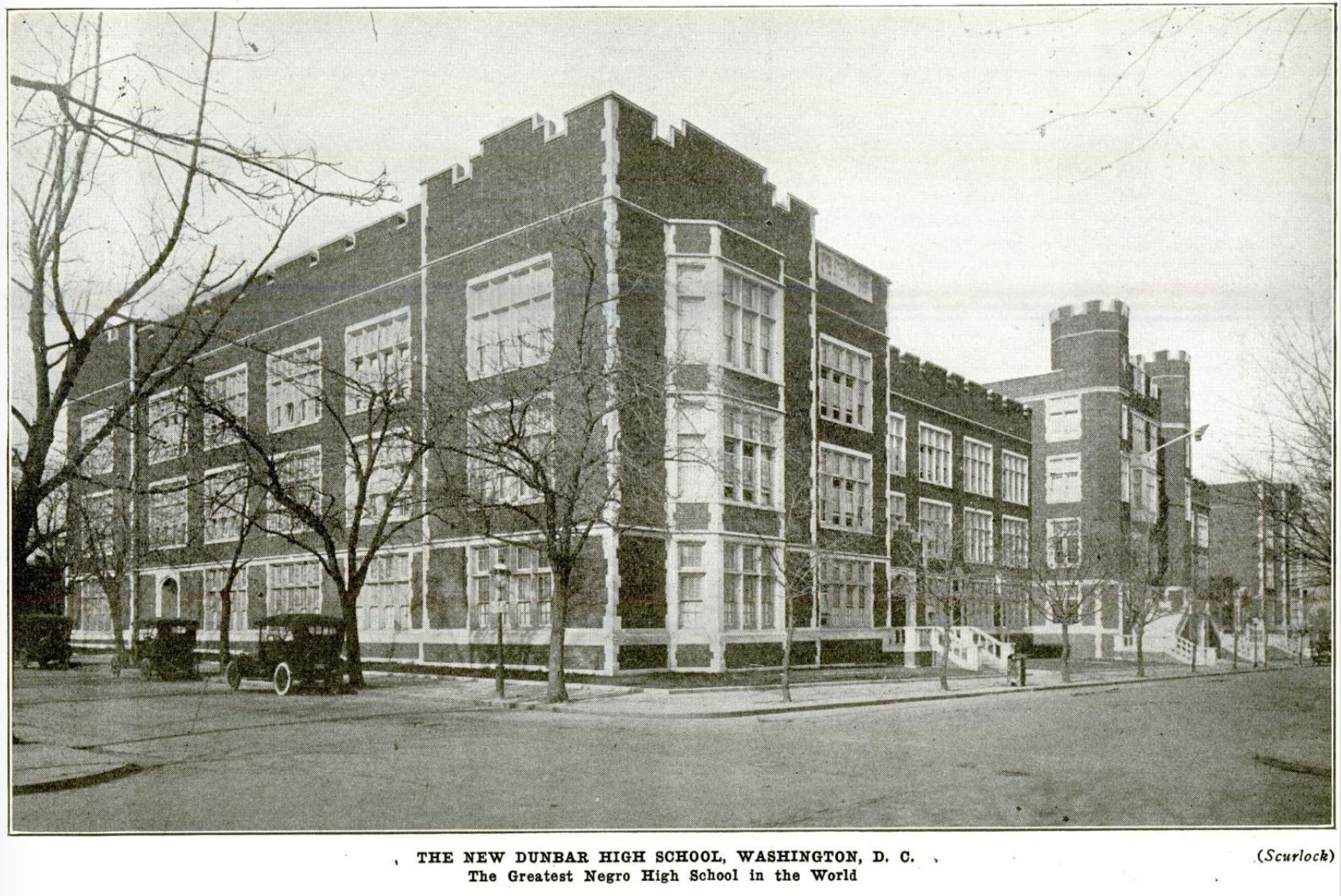

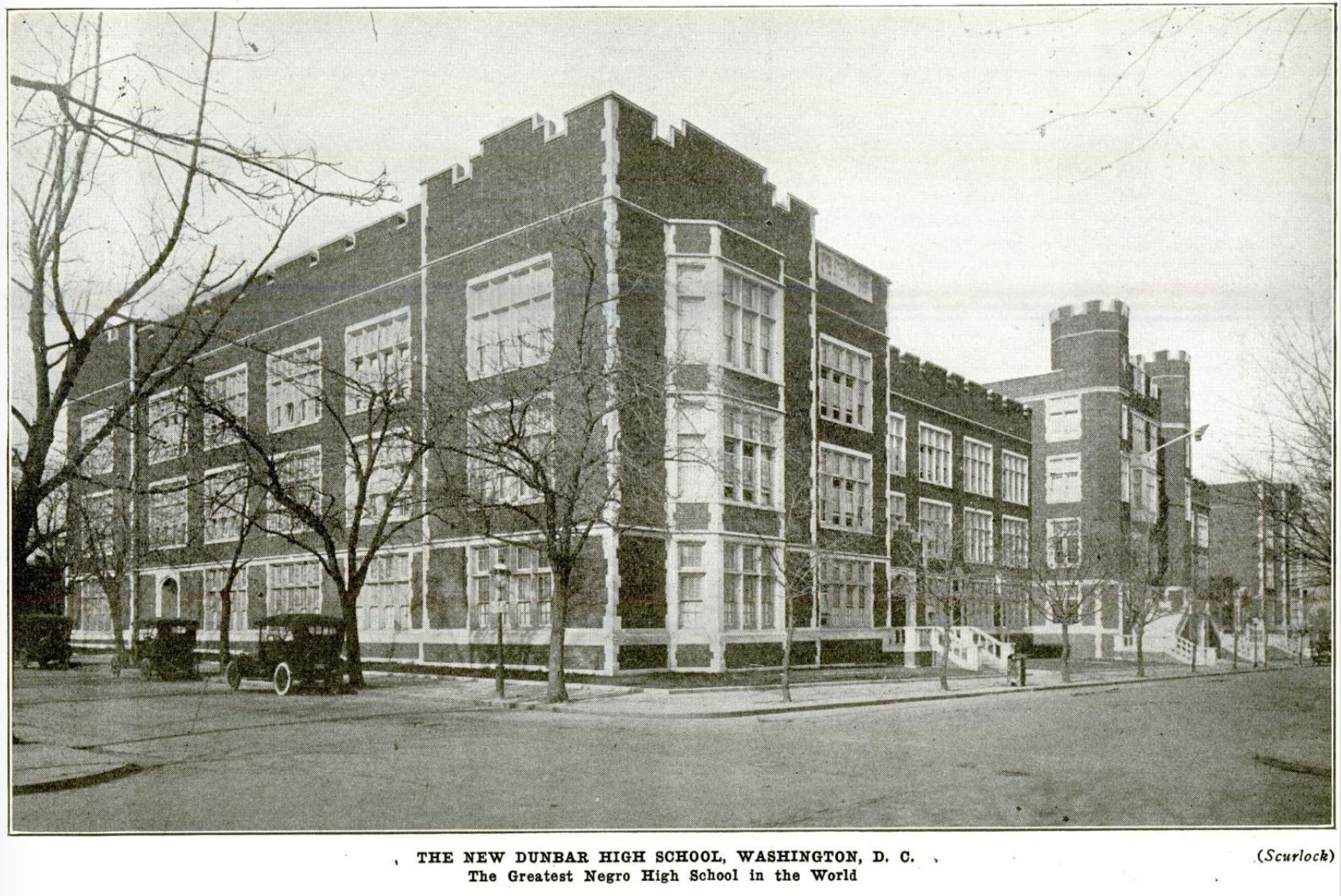

The M Street High School moved to new buildings and was renamed Dunbar School in 1916 for the noted African-American intellectual and poet,

Artists like Jackson responded to the lack of gallery support by pressing alternative public spaces into service, such as the "War Service and Recreation Center" of the Washington Y.M.C.A., where, in May 1919, a solo "exhibition of 25 sculptures of May Howard Johnson" was held.

The M Street High School moved to new buildings and was renamed Dunbar School in 1916 for the noted African-American intellectual and poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Paul Laurence Dunbar (June 27, 1872 – February 9, 1906) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Dayton, Ohio, to parents who had been enslaved in Kentucky before the American C ...

(d. 1906) (Jackson would complete a portrait in his honor, a casting of which, in bronze, would become the property of the school). The school's expansion brought new ambitions. Dunbar formed the Tanner Art League in 1919, and an attempt was made to institute an annual show for colored artists. The first show displayed the work of artists from fifteen states and included pieces from Laura Wheeler, Julian Abele

Julian Francis Abele (April 30, 1881April 23, 1950) was a prominent black American architect, and chief designer in the offices of Horace Trumbauer. He contributed to the design of more than 400 buildings, including the Widener Memorial Library ...

, Meta Warrick Fuller, and recent work from Jackson ("a bust and statuette"). The Dunbar's 1922 show included works by William Edouard Scott

William Edouard Scott (March 11, 1884 – May 15, 1964) was an African-American artist. Before Alain Locke asked African Americans to create and portray the '' New Negro'' that would thrust them into the future, artists like William Edouard Sc ...

and William McKnight Farrow, as well as the inaugural D.C. showing of Jackson's sculpture, ''The Brotherhood'', which had "had a prominent place in a recent exhibition of the Society of Independent Sculptors at the Waldorf Astoria," along with others of her work.

Teaching

In Washington, Jackson maintained a sculpture studio in her home. Aside from portrait sculpting, she continued to teach, with two years atHoward University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

as an art instructor for Howard's newly implemented School of art (1922–1924). At the university she taught and influenced James Porter, who went on to write one of the first comprehensive histories of African-American art. As an art historian, though, Porter was not impressed by her work and said that there was "no great originality in any of the pieces she attempted."

Recognition

With legalracial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

in force across the South since the turn of the century, topics such as racial mixing were taboo in general. Laws against miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is marriage or admixture between people who are members of different races or ethnicities. It has occurred many times throughout history, in many places. It has occasionally been controversial or illegal. Adjectives describin ...

had been proposed in both federal and state legislatures as far North as Massachusetts after Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (Cyprus) (DCY)

**Democratic Part ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

was elected as president in 1912

This year is notable for Sinking of the Titanic, the sinking of the ''Titanic'', which occurred on April 15.

In Albania, this leap year runs with only 353 days as the country achieved switching from the Julian to Gregorian Calendar by skippin ...

.

Her work was recognized with a Harmon Foundation Award in 1928. Five works were exhibited in the subsequent Harmon show, two featuring as illustration in the exhibition catalogue ("Bust of Dean Kelly Miller" and "Head of a Negro Child"). Leslie King-Hammond, an art historian, later praised Jackson's "efforts to address...without compromise and without sentimentality, the issues of race and class, especially as they affected mulatto

( , ) is a Race (human categorization), racial classification that refers to people of mixed Sub-Saharan African, African and Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry only. When speaking or writing about a singular woman in English, the ...

s".

Despite this recognition, Jackson was dissatisfied with her progress. 1929 she wrote, "I felt no satisfaction! Only deep sense of injustice, something that has followed me and my efforts all my life."

Race

Jackson could "pass" for Caucasian, but the racial politics of the early 20th century created an environment that pushed her in a different direction. She cooperated with pioneering African American anthropologistCaroline Bond Day

Caroline Stewart Bond Day (November 18, 1889 – May 5, 1948) was an American physical anthropologist, author, and educator. She was one of the first African-Americans to receive a degree in anthropology.

Day is recognized as a pioneer physical ...

, providing details (including photos) regarding the Howard family's racial background that would later be published in Day's 1932 Harvard University Master's thesis, ""A Study of Some Negro-White Families in the United States" (the year following Jackson's death)

Her personal experiences of racism were ongoing through her life and sour: whether her initial rejection from Corcoran Gallery or her experience with the National Academy of Design

The National Academy of Design is an honorary association of American artists, founded in New York City in 1825 by Samuel Morse, Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, Frederick Styles Agate, Martin E. Thompson, Charles Cushing Wright, Ithiel Town, an ...

. After showings in 1916 and 1918, the academy sent a representative to Jackson's home to ask if she was of "Negro blood"—and, on receiving an affirmative response, subsequently excluded her work from future exhibits.

Jackson expressed a fascination with the wide variety of phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

s among African Americans. This was expressed in "Shell-Baby in Bronze" (1914), "Head of a Negro Child" (1916), and "Mulatto Mother and Child" (1929) - the last piece in particular also an address of her own racial identity and "near Whiteness". These three pieces define her most original surviving work.

Her style was provocative for its time because it explored the features of America's multiracial society. As a result of not traveling in Europe, Jackson was somewhat isolated from her peers and was able to create her own vision that infused her work with a unique style. This style was ignored at first because it was so different from the popular style of the time. Though she had developed her own unique style, this style still adhered to academic tradition. Many galleries were not interested in her subject matter, as she dedicated most of her work to objective portraits of children, family members, and influential African Americans. It was not until the inauguration of the Harmon Foundation Awards, in 1926, for "Distinguished Negro Contributions," that there was even a National prize for Black Artists.

Jackson's racial identity was questioned after her death. While many may have questioned her racial identity it definitely became clear as she was listed as one of the colored women in the March 13, 1913 woman's suffrage parade.

Final years

The Harmon Foundation exhibits, intended to showcase the works of Black female artists in America, virtually coincided with events of theGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. The period's dream of the "New Negro Woman," lost its focus, and Jackson's death, in 1931, brought a period of obscurity during which crucial early cataloguing of her work was neglected. Her "sensitive and humanistic approach to the portrayal of Black Folk types," was in some ways anathema to certain "Black art critics and historians," uncomfortable with its portrayal of racial ambiguity in a period when the "near-white" were granted privilege unavailable to the darker-skinned.

Legacy

Jackson and her husband took in William's nephew Sargent Claude Johnson at age fifteen, following his parents' deaths (father, 1897, mother 1902). Johnson was one of six siblings, several of whom chose to live as white in their adulthood. Johnson, who went on to become a well-known sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance himself, was first exposed to sculpture through his aunt's work and studio. Jackson died in the year 1931, and is buried at theWoodlawn Cemetery Woodlawn Cemetery is the name of several cemeteries, including:

Canada

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Saskatoon)

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Nova Scotia)

United States

''(by state then city or town)''

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Ocala, Florida), where Isaac Rice and fa ...

in the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York City. Du Bois memorialized her death in his closing notes to the October 1931 issue of ''The Crisis'': "With her sensitive soul, she needed encouragement and contacts and delicate appreciation. Instead of this, she ran into the shadows of the Color Line... In the case of May Howard Jackson the contradictions and idiotic ramifications of the Color Line tore her soul asunder."

Francis T. Moseley was among the first to recognize the complex "daringly ventured to express in her work something of the social situation."

Jackson's contributions to American art were not widely appreciated until after her death, and a conclusive assessment of her work among "the Pantheon of great American Sculptors" remains to be determined. The African American Registry places her in the "annals of great American sculptors."

She was an artist who pushed the boundaries of her time, unique in the body of her work and vision. Her "completely American" training, initially derided as a lost opportunity to study with European masters, is now seen as an element vital to her status as a woman, if not a sculptor, of "intense and lucid temperament."

Exhibitions

Public exhibits

* The Veerhoff Gallery, Washington D.C. (1912, 1916) * The New York Emancipation Exhibition (1913) * The Corcoran Art Gallery (1915) * The National Academy of Design (1916) * ''May Howard Jackson: 25 Sculptures''. War Service and Recreation Center, Y.M.C.A., Washington, D.C. (May 1919) * Exhibit of Fine Arts by American Negro Artists, The Harmon Foundation, International House, New York (1929) * ''An Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture by American Negro Artists at the National Gallery of Art'' (1929)Posthumous group

* 3 Generations of African American Women Sculptors: A Study in Paradox (1996) Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, PhiladelphiaCatalogued work

* ''Slave boy'' / ''Portrait Bust of an African'' (1899) bronze, Kinsey Family Collection * ''Portrait Bust of'' ''Paul Lawrence Dunbar'' ( Dunbar High School, Washington D.C.). * ''Massachusetts Senator George Frisbie Hoar'' (1906) * ''Portrait Bust of W. E. B. Du Bois'' (1912) * ''Assistant Attorney General WIlliam H. Lewis'' (1912) * ''Morris Heights, New York City'' (1912) oil on linen, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts * ''Portrait Bust of Dean Kelly Miller'' (1914) bronze, Howard University) * ''Shell-baby'', bronze (1915, exhibited 1929) * ''Head of a Negro Child'' (1916). * ''William H. Lewis'' (bef 1919) * ''William Stanley Braitewait'' (bef 1919) * ''Portrait Bust of Reverend Francis J. Grimke'' (1922) * ''Suffer Little Children to Come Unto Me'' (n.d.) * ''Bust of a Young Woman'' (n.d., plaster, held byHoward University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

)

* ''Mulatto Mother and her Child'' / ''Mother and Child'', plaster ((exhibited 1918)

* ''William Tecumsah Sherman Jackson'' (exhibited 1929)

* Negro Dancing Girl (exhibited 1929)

* Resurrection, exhibited 1929)

Awards

* Harmon Foundation Award in the Fine Arts (1928) Bronze MedalReferences

Further reading

* * *External links

* * Includes a short biographical piece on William Sherman Jackson, husband of May Howard Jackson. African American firsts {{DEFAULTSORT:Jackson, May Howard 1877 births 1931 deaths African-American sculptors Artists from Philadelphia History of racism in the United States 20th-century American sculptors Sculptors from Pennsylvania 20th-century African-American women 20th-century African-American artists Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) 20th-century American women sculptors African-American women sculptors American women sculptors