May 1979 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following events occurred in May 1979:

The following events occurred in May 1979:

*The

*The

*The

*The

* USS ''Nautilus'', the first ever nuclear-powered submarine, ended its service after more than 25 years, arriving at the

* USS ''Nautilus'', the first ever nuclear-powered submarine, ended its service after more than 25 years, arriving at the

*

*

The following events occurred in May 1979:

The following events occurred in May 1979:

May 1, 1979 (Tuesday)

*TheRepublic of the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands, officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands, is an island country west of the International Date Line and north of the equator in the Micronesia region of the Northwestern Pacific Ocean.

The territory consists of 29 ...

was granted self-government within the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) was a United Nations trust territory in Micronesia administered by the United States from 1947 to 1994. The Imperial Japanese South Seas Mandate had been seized by the U.S. during the Pacifi ...

administered by the U.S., with a transition to full independence by 1986.

*Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

(Kalaallit Nunaat) was granted limited autonomy from Denmark, with its own Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and the capital, Godthåb being renamed Nuuk

Nuuk (; , formerly ) is the capital and most populous city of Greenland, an autonomous territory in the Kingdom of Denmark. Nuuk is the seat of government and the territory's largest cultural and economic center. It is also the seat of gove ...

. Jonathan Motzfeldt

Jonathan Jakob Jørgen Otto Motzfeldt (25 September 1938 – 28 October 2010) was a Greenlandic priest and politician. He is considered one of the leading figures in the establishment of Greenland Home Rule.

was inaugurated as the first prime minister of Greenland

The prime minister of Greenland (; ), also known as the premier of Greenland,Members of the Cabinet

G ...

and served for almost 12 years. The 31-member G ...

Inatsisartut

The Inatsisartut (, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Greenland in English, is the unicameral parliament (legislative branch) of Greenland, an autonomous territoryMultiple sources:

*

*

* in the Danish Realm. Established in 1979, the parli ...

was sworn in as the first Greenlandic parliament.

*Malacañang Palace

Malacañang Palace (, ), officially known as Malacañán Palace, is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the Philippines. It is located in the Manila district of San Miguel, Manila, San Miguel, along Jose Laurel S ...

, the presidential residence of the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

in Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

, was reopened after two years of remodeling and rebuilding.

*American Communist Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American Marxist and feminist political activist, philosopher, academic, and author. She is Distinguished Professor Emerita of Feminist Studies and History of Consciousness at the University of ...

was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize (, ''mezhdunarodnaya Leninskaya premiya mira)'' was a Soviet Union award named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a panel appointed by the Soviet government, to notable individuals whom the panel ...

by the Soviet Union.

*Born: Mauro Bergamasco, Italian rugby union flanker with 106 appearances for the Italian national team; in Padova

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of ...

*Died:

**Ayatollah Morteza Motahhari

Morteza Motahhari (; 31 January 1919 – 1 May 1979) was an Iranian Twelver Shia scholar, philosopher, lecturer. Motahhari is considered to have an important influence on the ideologies of the Islamic Republic, among others. He was a co-found ...

, Iranian Shia Muslim theologian, Chairman of the Council of the Islamic Revolution

The Council of the Islamic Revolution () was a group formed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to manage the Iranian Revolution on 10 January 1979, shortly before he returned to Iran. "Over the next few months there issued from the council hundreds ...

and a close associate of the Ayatollah Khomeini, was assassinated in Tehran by the Forghan Fighters, an underground group that had killed General Vali Gharani on April 23. Motahari was leaving a dinner party at the home of Iran's Minister of Revolutionary Affairs at 10:20 in the evening, and was shot as he walked to his car.

**Sérgio Paranhos Fleury

Sérgio Fernando Paranhos Fleury (19 May 1933 – reported deceased as of 1 May 1979) was a Brazilian police deputy during the Brazilian military dictatorship. He was chief of ''DOPS'', the Brazilian "", which had a major role during the years ...

, 45, Brazilian law enforcement official and chief of the agency DOPS (Departamento de Ordem Política e Social or the Department for Political and Social Order), drowned before he could be tried.

May 2, 1979 (Wednesday)

*TheHouston Angels

The Houston Angels was a team that played for two seasons in the Women's Professional Basketball League. The team won the league championship in the inaugural season defeating the Iowa Cornets three games to two in the best-of-five tournament. The ...

won the first championship of the Women's Professional Basketball League

The Women's Professional Basketball League (abbreviated WBL) was a professional women's basketball league in the United States. The league played three seasons from the fall of 1978 to the spring of 1981. The league was the first professional w ...

(WPBL), the first pro basketball circuit for women, winning the fifth game of the best-3-of-5 series against the Iowa Cornets. Houston won the first two games, Iowa the second two, setting up the deciding game, which Houston won, 111 to 104 with Paula Mayo being the high scorer with 36 points.

*Died: Julius Kravitz, 67, American grocery chain executive and chairman of First National Supermarkets, was fatally wounded during a kidnapping attempt the day before in Shaker Heights, Ohio

Shaker Heights is a city in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city's population was 29,439. Shaker Heights is an inner-ring streetcar suburb of Cleveland, abutting the eastern edge of the c ...

, a suburb of Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

. Kravitz was shot three times in the chest and once in the back by two men masquerading as police officers. Police arrested the former president of Multi-Chem Industries and another Multi-Chem employee.

May 3, 1979 (Thursday)

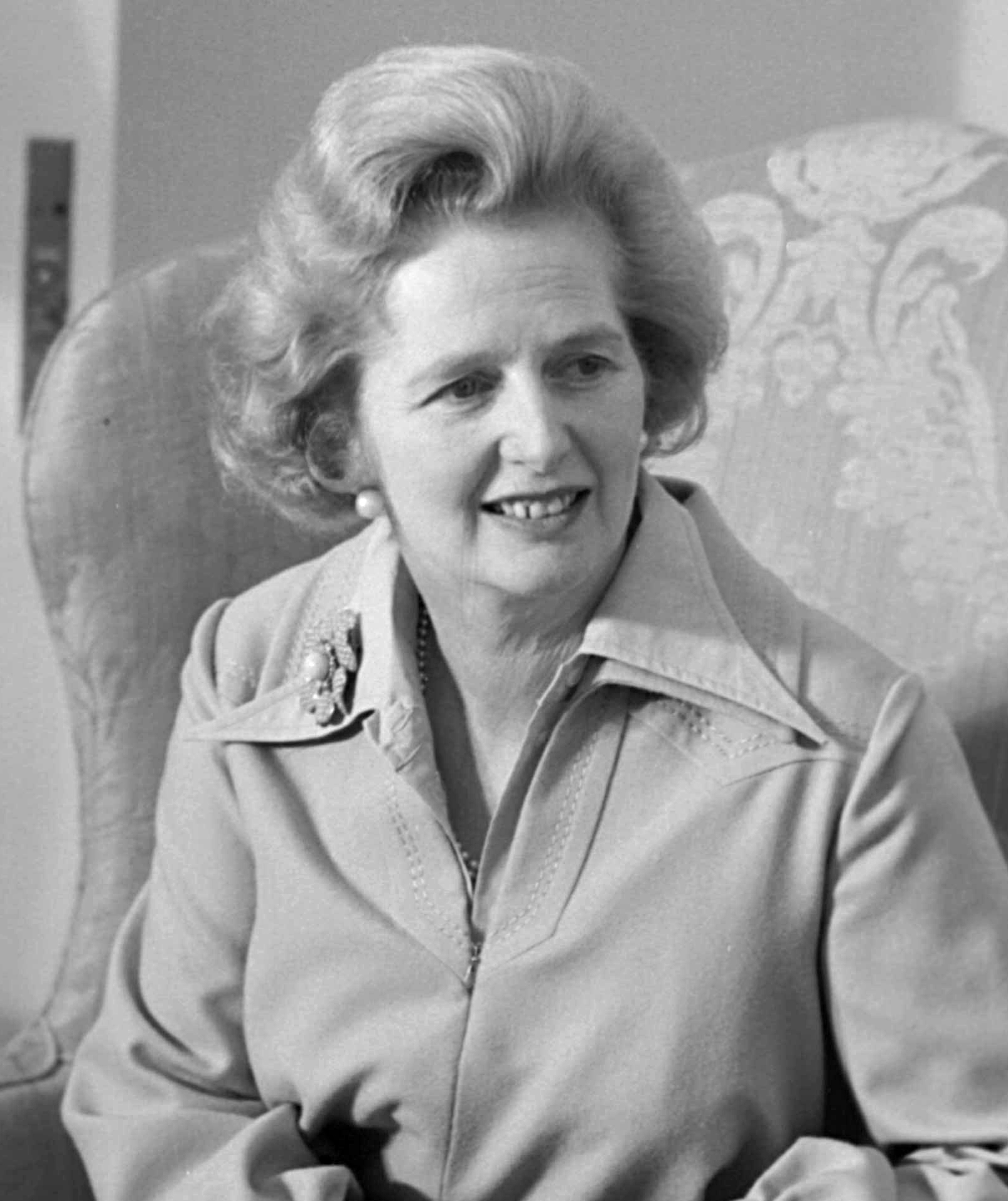

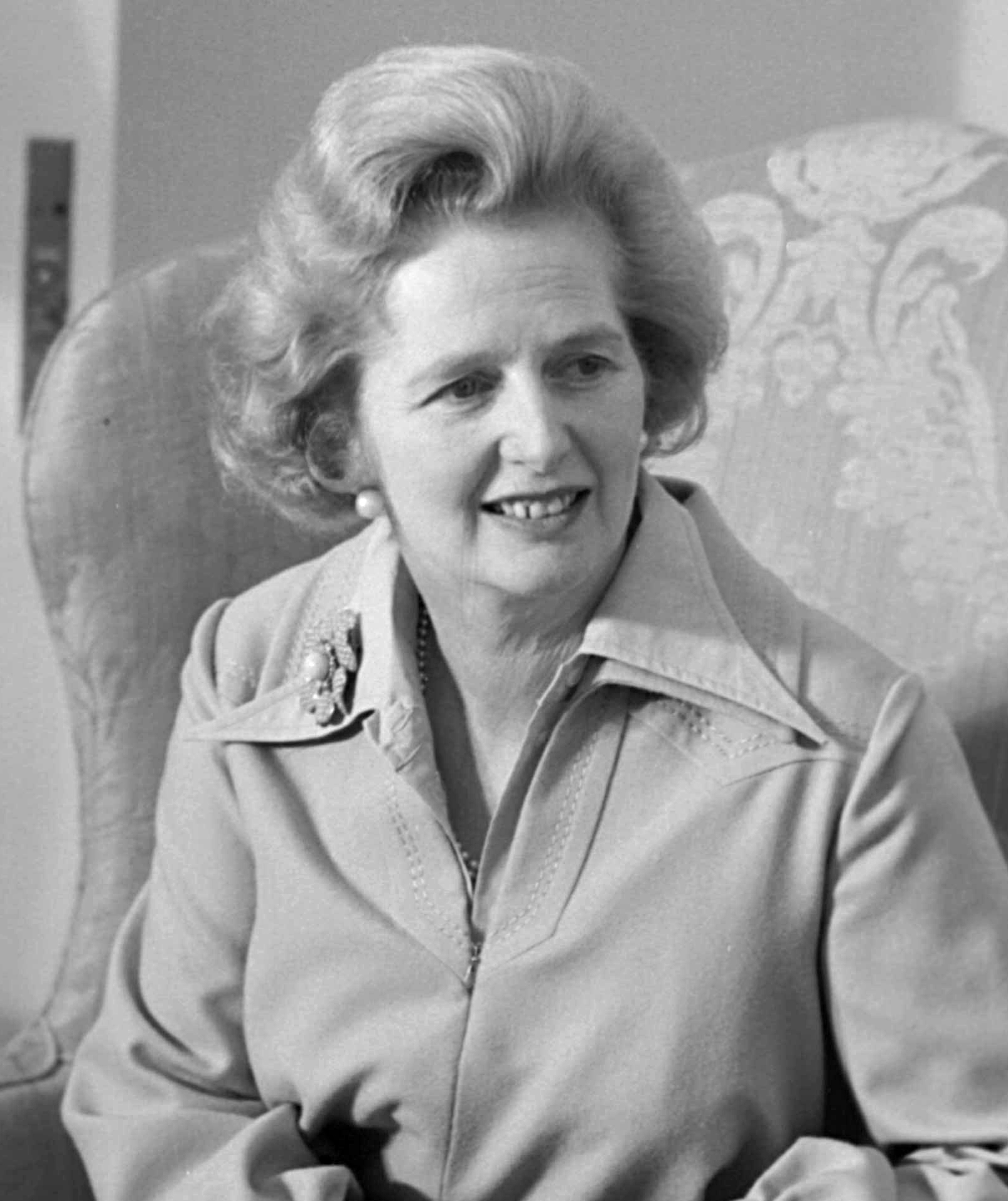

* Voting for the House of Commons took place in the UK and the Conservative Party won a 339-seat majority of the 635 Commons seats, makingMargaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

the nation's first woman prime minister and ending the government of James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the L ...

and the Labour Party. Among the candidates becoming MPs for the first time was future prime minister John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

, representing the County Huntingdonshire constituency, formerly occupied by David Renton

David Lockhart-Mure Renton, Baron Renton, (12 August 1908 – 24 May 2007) was a British politician who served for over 60 years in Parliament, 34 in the House of Commons and then 28 in the House of Lords.

Renton was Member of Parliament f ...

, who departed Commons to take a seat in the House of Lords.

*The last U.S. Army soldier for the United States Taiwan Defense Command

The United States Taiwan Defense Command (USTDC; zh, t=美軍協防台灣司令部) was a sub-unified command of the United States Armed Forces operating in Taiwan from December 1954 to April 1979.

History

The United States Taiwan Defense Comm ...

left the island of Taiwan.

*Ted Giannoulas, the originator of the oldest pro baseball team mascot, the " San Diego Chicken", was fired by radio station KGB-FM

KGB-FM (101.5 MHz) is a commercial radio station licensed to San Diego, California. It is owned and operated by iHeartMedia and broadcasts in a classic rock music format. KGB-FM's studios are located in San Diego's Kearny Mesa neighborhood o ...

after five seasons of wearing the costume of what was originally called the "KGB Chicken". When San Diego Padre fans learned that another radio station employee had been substituted for Giannoulas, the replacement was booed off the field. After a successful lawsuit, Giannoulas returned in a different costume with a different mascot name, "The Famous Chicken", on June 29.

May 4, 1979 (Friday)

*Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

, leader of Britain's Conservative Party, took office as the first woman to be Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

. Shortly after noon, Prime Minister James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the L ...

submitted his resignation to Queen Elizabeth II and, a few minutes later, Thatcher accepted the Queen's request to form a new government, after which Thatcher went directly to her new office at 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London is the official residence and office of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. Colloquially known as Number 10, the building is located in Downing Street, off Whitehall in th ...

.

*The independent low cost British airline Air Europe began commercial service, with a Boeing 737 flight that departed London Gatwick Airport

Gatwick Airport , also known as London Gatwick Airport (), is the Airports of London, secondary international airport serving London, West Sussex and Surrey. It is located near Crawley in West Sussex, south of Central London. In 2024, Gatwic ...

to take vacationers to the Spanish resort of Palma de Mallorca

Palma (, ; ), also known as Palma de Mallorca (officially between 1983 and 1988, 2006–2008, and 2012–2016), is the capital and largest city of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of the Balearic Islands in Spain. It is ...

on the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

. The airline would exist until going bankrupt in 1991.

*The first Team Ice Racing World Championship

The FIM Ice Speedway of Nations, formerly known as the Ice Speedway Team World Championship, is an international ice speedway competition, first held in Kalinin (Tver), USSR, in 1979. Since its establishment, the tournament has been noted by a ...

(the racing of motorcycles on a frozen surface in a motorcycle speedway

Motorcycle speedway, usually referred to simply as speedway, is a motorcycle sport involving four and sometimes up to six riders competing over four clockwise, anti-clockwise laps of an oval circuit. The motorcycles are specialist machines that ...

) with the Soviet Union finishing first, Czechoslovakia second and West Germany third.

*Born:

**Lance Bass

James Lance Bass (; born May 4, 1979) is an American singer, actor, and producer. He grew up in Mississippi and rose to fame as the Bass (voice type), bass singer for the boy band NSYNC. The band has sold over 70 million records, becoming one of ...

, American singer (for NSYNC

NSYNC ( ; also stylized as *NSYNC or N Sync) was an American vocal group and pop boy band formed by Chris Kirkpatrick in Orlando, Florida, in 1995 and launched in Germany by BMG Ariola Munich. The group consists of Kirkpatrick, JC Chasez, ...

) and record producer; in Laurel, Mississippi

Laurel is a city in and the second county seat of Jones County, Mississippi, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 17,161. Laurel is northeast of Ellisville, the first county seat, which contains the first county ...

**Wes Butters

Wesley Paul Butters (born 4 May 1979) is a radio broadcaster, formerly of BBC Radio 1, and writer.

Early life

Butters attended Buile Hill High School in Pendleton, Salford, and studied at the University of Salford between 1995 and 1997, wh ...

, English radio broadcaster; in Salford

Salford ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Greater Manchester, England, on the western bank of the River Irwell which forms its boundary with Manchester city centre. Landmarks include the former Salford Town Hall, town hall, ...

, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated ''Lancs'') is a ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Cumbria to the north, North Yorkshire and West Yorkshire to the east, Greater Manchester and Merseyside to the south, and the Irish Sea to ...

** Réhahn (Rehahn Croquevielle), French photographer and cultural preservationist; in Bayeux

Bayeux (, ; ) is a commune in the Calvados department in Normandy in northwestern France.

Bayeux is the home of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. It is also known as the fir ...

*Died:

**Leif Erland Andersson

Leif Erland Andersson (4 November 1943 – 4 May 1979) was a Swedish astronomer.

Early life

Andersson had been a child prodigy who won the Swedish television quiz show ''10.000-kronorsfrågan'' ("The 10,000 Kronor Question") at the age of 16 ...

, 35, Swedish astronomer who calculated the first observable astronomical transits of the planet Pluto

** Elisabeth von Dyck, 27, West German militant and suspected member of the Red Army Faction

The Red Army Faction (, ; RAF ),See the section "Name" also known as the Baader–Meinhof Group or Baader–Meinhof Gang ( ), was a West German far-left militant group founded in 1970 and active until 1998, considered a terrorist organisat ...

, was shot in the back as by police in Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

as she was seen running into a suspected Faction safe house.

May 5, 1979 (Saturday)

*TheIslamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), also known as the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, is a multi-service primary branch of the Islamic Republic of Iran Armed Forces, Iranian Armed Forces. It was officially established by Ruhollah Khom ...

, more commonly called the "Revolutionary Guards" in the Western press and "the Sepâh" in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, was formed following an April 22 decree of the Ayatollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini (17 May 1900 or 24 September 19023 June 1989) was an Iranian revolutionary, politician, political theorist, and religious leader. He was the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the main leader of the Iranian ...

as an intelligence agency and an internal security bureau to investigate and counteract anti-government activity. The Revolutionary Guards would later be designated by the United States and by Saudi Arabia as a terrorist organization

Several national governments and two international organizations have created lists of organizations that they designate as terrorist. The following list of designated terrorist groups lists groups designated as terrorist by current and former ...

.

*The U.S. Secret Service arrested a man at the Civic Center Mall in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, 10 minutes before U.S. president Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

was scheduled to address a crowd, and found him carrying what appeared to be a pistol. Raymond Lee Harvey was carrying a starter pistol loaded with blank rounds, and told police that he had been hired to fire the blanks into the ground as a distraction in order for Carter to be assassinated by a sniper team that was stationed in the Alan Hotel overlooking the plaza. Los Angeles police found a shotgun case (but not a weapon) and three unspent bullets in the hotel room identified by Harvey.

*In the United Kingdom, "Radio Lollipop

Radio Lollipop is a charitable organization providing a care, comfort, play and entertainment service for children in hospital. It organizes Volunteer Playmakers to spend time with children in wards or in special play areas, taking its name fro ...

" began broadcasting as a low-power radio station with children's programming intended for the benefit of patients at Queen Mary's Hospital for Children in Carshalton

Carshalton ( ) is a town, with a historic village centre, in south London, England, within the London Borough of Sutton. It is situated around southwest of Charing Cross and around east by north of Sutton town centre, in the valley of the Rive ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

. The network was then expanded to serve other children's hospitals and hospital wards in the UK and later to Australia, New Zealand, the United States (in Miami and Houston) and South Africa.

*At the Pista di prova di Nardò della Fiat, a test track in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

for the automaker Fiat

Fiat Automobiles S.p.A., commonly known as simply Fiat ( , ; ), is an Italian automobile manufacturer. It became a part of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles in 2014 and, in 2021, became a subsidiary of Stellantis through its Italian division, Stellant ...

at the town of Nardò

Nardò ( or ; ) is a town and ''comune'' in the southern Italian region of Apulia, in the Province of Lecce.

Lies on a lowland area placed at south-west of its Province, its border includes part of the Ionian coast of Salento.

For centuries, i ...

, a commercially available automobile exceeded for the first time, covering the track in slightly less than two minutes at an average speed of .

*British commercial diver B. Eke drowned when his diving helmet

A diving helmet is a rigid head enclosure with a breathing gas supply used in underwater diving. They are worn mainly by professional divers engaged in surface-supplied diving, though some models can be used with scuba equipment. The upper par ...

came off during a surface-orientated dive to conduct routine maintenance on fixed platform 48/29C in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

.

May 6, 1979 (Sunday)

* Parliamentary elections were held in Austria for the 183 seats of the ''Nationalrat''. TheSocial Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Form ...

, led by Chancellor Bruno Kreisky

Bruno Kreisky (; 22 January 1911 – 29 July 1990) was an Austrian social democratic politician who served as foreign minister from 1959 to 1966 and as chancellor from 1970 to 1983. Aged 72, he was the oldest chancellor after World War II.

Kr ...

, increased its slim majority from 93 to 95 seats.

*The first large protest against nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by ...

since the Three Mile Island disaster, organized by Timothy Massad

Timothy George Massad (born July 30, 1956) is an American lawyer and government official who served as the chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) under President Barack Obama. He had previously been Assistant Secretary for F ...

and Donald K. Ross, took place in Washington, D.C., and attracted between 65,000 and 125,000 demonstrators.

*To call attention to its campaign for the independence of the island of Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

from France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, the Fronte di liberazione naziunale di a Corsica (FLNC) carried out the simultaneous bombing of 20 bank branches in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

.

*Born:

**Gerd Kanter

Gerd Kanter (born 6 May 1979) is a retired Estonian discus thrower. He was the 2007 World Champion in the event and won the gold medal at the 2008 Summer Olympics, and bronze in London 2012. His personal best throw of 73.38 m is the Estonia ...

, Estonian discus thrower, 2007 world champion and 2008 Olympic gold medalist; in Tallinn

Tallinn is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Estonia, most populous city of Estonia. Situated on a Tallinn Bay, bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, it has a population of (as of 2025) and ...

, Soviet-occupied Estonia

**Jon Montgomery

Jonathan Riley "Jon" Montgomery (born May 6, 1979, in Russell, Manitoba) is a Canadian skeleton racer and television host. He won the gold medal in the men's skeleton event at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, British Columbia. Despite hos ...

, Canadian athlete and 2010 Olympic gold medalist in the skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

individual sled racing competition; in Russell, Manitoba

Russell is an unincorporated urban community in the Municipality of Russell-Binscarth in Manitoba, Canada.

It is located along PTH 16 and PTH 83, and is at the western terminus of PTH 45. Russell is approximately east of the Saskatchewan bo ...

**Benita Willis

Benita Jaye Willis (born 6 May 1979 in Mackay, Queensland) is an Australian long-distance runner, who is a three-time national champion in the women's 5,000 metres. Her foremost achievement is a gold medal in the long race at the 2004 IAAF Worl ...

, Australian long-distance runner and gold medalist in the women's cross country race in the 2004 world championships; in Mackay, Queensland

}

Mackay () is a city in the Mackay Region on the eastern or Coral Sea coast of Queensland, Australia. It is located about north of Brisbane, on the Pioneer River. Mackay is described as being in either Central Queensland or North Queensland ...

*Died: Joe Hooper, 40, U.S. Army captain and Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

recipient for heroism during the Vietnam War in 1968, died of a cerebral hemorrhage

May 7, 1979 (Monday)

*British pilot Gerry Breen set a distance record, which still stands, for a flight on apowered hang glider

A foot-launched powered hang glider (FLPHG), also called powered harness, nanolight, or hangmotor, is a powered hang glider harness with a motor and propeller often in pusher configuration, although some can be found in tractor configuration. ...

, flying from a location in Wales to Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

, using a Soarmaster, the flight took about 4 hours with a tailwind of about 25 knots (29 mph) and reportedly consumed only of fuel.

May 8, 1979 (Tuesday)

*Eleven people, all but one of them shoppers, died in a fire at the Woolworth's department store, a six-storey tall building in downtownManchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

in England. The fire was later traced to an electrical cable on the third floor behind furniture, fueled by highly flammable and toxic polyurethane

Polyurethane (; often abbreviated PUR and PU) is a class of polymers composed of organic chemistry, organic units joined by carbamate (urethane) links. In contrast to other common polymers such as polyethylene and polystyrene, polyurethane term ...

foam inside the cushions.

*Police in San Salvador

San Salvador () is the Capital city, capital and the largest city of El Salvador and its San Salvador Department, eponymous department. It is the country's largest agglomeration, serving as the country's political, cultural, educational and fin ...

, capital of the Central American nation of El Salvador

El Salvador, officially the Republic of El Salvador, is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south by the Pacific Ocean. El Salvador's capital and largest city is S ...

, fired on a crowd of 300 anti-government demonstrators who had taken control of the Metropolitan Cathedral, killing 22 and wounding 38 others.

*The legality of the business model of Amway

Amway Corp. (short for "American Way") is an American multi-level marketing (MLM) company that sells health, beauty, and home care products. The company was founded in 1959 by Jay Van Andel and Richard DeVos and is based in Ada Township, Michi ...

, a direct sales company that enlists individuals as its distributors of its own manufactured cleaning products, nutritional supplements, and beauty care products, was certified by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) United States antitrust law, antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. It ...

in its ruling in ''In re Amway Corp.

IN, In or in may refer to:

Dans

* India (country code IN)

* Indiana, United States (postal code IN)

* Ingolstadt, Germany (license plate code IN)

* In, Russia, a town in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

Businesses and organizations

* Independen ...

'', more than four years after the FTC had filed a complaint against the corporation.

*The Islamic Republic of Iran executed 21 former members of the Imperial government, including Majlis speaker Javad Saeed

Javad Saeed () was an Iranian politician who served as the last Speaker of the Parliament of Iran during Pahlavi dynasty, and was the last secretary-general of the ruling Resurgence Party. He represented Sari in the parliament. He resigned from ...

, Information Minister Gholam Reza Khanpour, Education Minister Mohammad Reza Ameli Tehrani

Mohammad Reza "Ajir" Ameli Tehrani () (31 December 1927 – 8 May 1979) was an Iranian physician and pan-Iranist politician. He served as a minister in the cabinets of Jafar Sharif-Emami and Gholam-Reza Azhari. He was sentenced to death by the Re ...

, Armored Division Brigadier General Ali Fathi Amin, and 15 officers of the SAVAK, the Shah's secret police.

Died: Talcott Parsons

Talcott Parsons (December 13, 1902 – May 8, 1979) was an American sociologist of the classical tradition, best known for his social action theory and structural functionalism. Parsons is considered one of the most influential figures in soci ...

, 76, American sociologist at Harvard University, known for his 1937 book ''The Structure of Social Action

''The Structure of Social Action'' is a 1937 book by sociologist Talcott Parsons.

In 1998 the International Sociological Association listed the work as the ninth most important sociological book of the 20th century, behind Jürgen Habermas

J ...

'' and the social action theory

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

approach to the study of group behavior, died during a trip to Heidelberg University in West Germany, the day after delivering a lecture.

May 9, 1979 (Wednesday)

*California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

became the first U.S. state since World War II to authorize limits on the purchase of gasoline

Gasoline ( North American English) or petrol ( Commonwealth English) is a petrochemical product characterized as a transparent, yellowish, and flammable liquid normally used as a fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines. When for ...

, implementing an "odd–even rationing

Odd–even rationing is a method of rationing in which access to some resource is restricted to some of the population on any given day. In a common example, drivers of private vehicles may be allowed to drive, park, or purchase gasoline on altern ...

" system after a shortage of fuel that had caused long lines of vehicles outside service stations since April 27. The system went into effect at 12:01 a.m. in nine of California's 11 largest counties (out of 58), containing two-thirds of the states 15 million licensed drivers. Affected were the counties of Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

, Orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

** Orange juice

*Orange (colour), the color of an orange fruit, occurs between red and yellow in the vi ...

, Ventura, Santa Clara, Alameda

An alameda is a street or path lined with trees () and may refer to:

Places Canada

* Alameda, Saskatchewan, town in Saskatchewan

** Grant Devine Dam, formerly ''Alameda Dam'', a dam and reservoir in southern Saskatchewan

Chile

* Alameda (Santi ...

, Marin, and Contra Costa, but the county supervisors of San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, and San Mateo turned down the proposal. Under the rules, only private four-wheeled vehicles that had license plates ending in an odd number

In mathematics, parity is the property of an integer of whether it is even or odd. An integer is even if it is divisible by 2, and odd if it is not.. For example, −4, 0, and 82 are even numbers, while −3, 5, 23, and 69 are odd numbers.

The ...

would be allowed to purchase fuel on odd-numbered days, and those with an even number on even numbered days. All vehicles were allowed to buy on the 31st of the month, and personalized plates without a number were exempted as long as they met the rules of having a tank less than half full.

*King Juan Carlos of Spain

Juan Carlos I (; Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 November 1975 until his abdication on 19 June 2014. In Sp ...

opened the first democratically elected parliament in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

since the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

of 1936.

*U.S. secretary of state Cyrus Vance

Cyrus Roberts Vance (March 27, 1917January 12, 2002) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as the 57th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United ...

and U.S. defense secretary Harold Brown announced at a press conference that the United States and the Soviet Union had reached a basic agreement on negotiations during the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds of ...

for limitations on long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles and on aircraft carrying nuclear weapons. Two days later, the White House announced that U.S. president Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

would meet in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

on June 15.

*Northwestern University

Northwestern University (NU) is a Private university, private research university in Evanston, Illinois, United States. Established in 1851 to serve the historic Northwest Territory, it is the oldest University charter, chartered university in ...

graduate student John Harris sustained minor cuts after opening a package addressed to him by Ted Kaczynski

Theodore John Kaczynski ( ; May 22, 1942 – June 10, 2023), also known as the Unabomber ( ), was an American mathematician and domestic terrorist. He was a mathematics prodigy, but abandoned his academic career in 1969 to pursue a reclusi ...

, dubbed "the Unabomber" by the press, and was the Unabomber's second victim overall. Almost a year earlier, on May 25, 1978, Northwestern University police officer Terry Marker had been hurt after opening a suspicious package that had been intended for N.U. professor Buckley Crist.

*Born: Pierre Bouvier

Pierre Bouvier (born May 9, 1979) is a Canadian singer and musician best known for being the lead vocalist and studio bassist of the rock band Simple Plan.

He hosted the MTV reality show '' Damage Control''.

Filmography

Discography

...

, Canadian rock musician (Simple Plan

Simple Plan is a Canadian rock band formed in Montreal, Quebec, in 1999. The band's current lineup consists of Pierre Bouvier (lead vocals, studio bass guitar), Chuck Comeau (drums), Jeff Stinco (lead guitar), and Sébastien Lefebvre (rhyt ...

), in Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

*Died:

**Habib Elghanian

Habib (Habibollah) Elghanian (; 5 April 1912 – 9 May 1979) was a prominent Iranian Jewish businessman and philanthropist who served as the president of the Tehran Jewish Society and acted as the symbolic head of the Iranian Jewish community i ...

, 67, Iranian businessman and unofficial leader of Iran's Jewish community during the 1970s, was shot by a firing squad a little more than two months after having been arrested on accusations that he was a spy for Israel. Elghanian's execution, the first under the rule of the Ayatollah Khomeini of someone other than a former government or military official, prompted the departure of most of the 80,000 Jewish residents of Iran.

** Salvador Balbuena, 29, Spanish professional golfer, died of a heart attack the night before he was scheduled to play in the Open de France

The Open de France is a European Tour golf tournament. Inaugurated in 1906 it is the oldest national open in Continental Europe and has been part of the European Tour's schedule since the tour's inception in 1972. The 100th edition of the event ...

tournament.

May 10, 1979 (Thursday)

*For the first time in American history, the price of a gallon of gasoline cost more than one U.S. dollar, with aGulf

A gulf is a large inlet from an ocean or their seas into a landmass, larger and typically (though not always) with a narrower opening than a bay (geography), bay. The term was used traditionally for large, highly indented navigable bodies of s ...

station in the Beacon Hill section of Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, raising its price for premium unleaded gas from 98.9 cents to $1.009.

Federated States of Micronesia

The Federated States of Micronesia (, abbreviated FSM), or simply Micronesia, is an island country in Micronesia, a region of Oceania. The federation encompasses the majority of the Caroline Islands (excluding Palau) and consists of four Admin ...

became self-governing after four of the seven constituent members of the United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) was a United Nations trust territory in Micronesia administered by the United States from 1947 to 1994. The Imperial Japanese South Seas Mandate had been seized by the U.S. during the Pacifi ...

ratified the FSM Constitution. The island groups of Yap

Yap (, sometimes written as , or ) traditionally refers to an island group located in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, a part of Yap State. The name "Yap" in recent years has come to also refer to the state within the Federate ...

, Truk, Pohnpei

Pohnpei (formerly known as Ponape or Ascension, from Pohnpeian: "upon (''pohn'') a stone altar (''pei'')") is an island of the Senyavin Islands which are part of the larger Caroline Islands group. It belongs to Pohnpei State, one of the fou ...

and Kosrae

Kosrae ( ), formerly known as Kusaie or Strong's Island, is an island in the Caroline Islands archipelago, and States of Micronesia, state within the Federated States of Micronesia. It includes the main island of Kosrae, traditionally known as Ual ...

were initially governed by President Tosiwo Nakayama

was the first President of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). He served two terms from 1979 until 1987.

Biography

Nakayama was born on November 23, 1931, on Pisaras, part of Namonuito Atoll in what is now Chuuk State. At the time of his ...

, who would oversee the transition of the associated state to an independent republic on November 3, 1986.

*The U.S. House of Representatives voted 246 to 159 against giving U.S. president Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

the authority to produce a standby plan for the rationing of gasoline. The U.S. Senate had approved the plan, 58 to 39, the day before.

*Born:

**Lee Hyo-ri

Lee Hyo-ri (; born May 10, 1979) is a South Korean singer. She debuted as a member of group Fin.K.L in 1998, which became one of the most popular girl groups in South Korea during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Aside from Fin.K.L, she has al ...

, bestselling South Korean pop singer and actress; in Osong-ri, North Chungcheong Province

North Chungcheong Province (), also known as Chungbuk, is a province of South Korea. North Chungcheong has a population of 1,578,934 (2014) and has a geographic area of located in the Hoseo region on the south-centre of the Korean Peninsula. No ...

**Marieke Vervoort

Marieke Vervoort (10 May 1979 – 22 October 2019) was a Belgian Paralympic athlete with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. She won several medals at the Paralympics, and she received worldwide attention in 2016 when she revealed that she was cons ...

, Belgian Paralympic gold medalist and proponent of the euthanasia

Euthanasia (from : + ) is the practice of intentionally ending life to eliminate pain and suffering.

Different countries have different Legality of euthanasia, euthanasia laws. The British House of Lords Select committee (United Kingdom), se ...

; in Diest

Diest () is a city and municipality located in the Belgian province of Flemish Brabant. Situated in the northeast of the Hageland region, Diest neighbours the provinces of Antwerp to its North, and Limburg to the East and is situated around ...

(d. 2019)

*Died:

**Cyrus S. Eaton

Cyrus Stephen Eaton Sr. (December 27, 1883 – May 9, 1979) was a Canadian-American investment banker, businessman and philanthropist, with a career that spanned 70 years.

For decades Eaton was one of the most powerful financiers in the American ...

, 95, Canadian-born American financier and railroad executive

**Charles Frankel

Charles Frankel (December 13, 1917 – May 10, 1979) was an American philosopher, Assistant U.S. Secretary of State, professor and founding director of the National Humanities Center.

Early life and personal life

Born into a Jewish family in N ...

, 61, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs

The assistant secretary of state for educational and cultural affairs is the head of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, a bureau within the United States Department of State. The assistant secretary of state for educational and cu ...

and president of the National Humanities Center The National Humanities Center (NHC) is an independent institute for advanced study in the humanities located in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, United States. The NHC operates as a privately incorporated nonprofit and is not part of any uni ...

, was shot and killed at his home in Bedford Hills, New York

Bedford Hills is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in the town of Bedford, Westchester County, New York, United States. The population was 3,001 at the 2010 census.

Two New York State prisons for women, Bedford Hills Correction ...

, along with his wife, the apparent victims of a burglary.

May 11, 1979 (Friday)

*Eight children ranging in age from 8 to 13 years old were killed in theLebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

village of Babiliye, south of Sidon

Sidon ( ) or better known as Saida ( ; ) is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast in the South Governorate, Lebanon, South Governorate, of which it is the capital. Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre, t ...

, after they had become curious about a live artillery shell that had landed in their neighborhood during a clash between Christian militiamen and Palestinian guerrillas.

*Eight oil workers were killed in the sudden collapse of ''Ranger 1'', an oil drilling platform in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

, about offshore from Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a Gulf Coast of the United States, coastal resort town, resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island (Texas), Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a pop ...

. Another 26 were rescued at sea, and the eight dead were believed to have been inside the structure when it fell into the sea less than four minutes after one of its three supports broke.

*Died:

**Barbara Hutton

Barbara Woolworth Hutton (November 14, 1912 – May 11, 1979) was an American debutante, socialite, heiress and philanthropist. She was dubbed the "Poor Little Rich Girl"—first when she was given a lavish and expensive debutante ball in 1930 ...

, 66, American socialite and philanthropist known as the "Poor Little Rich Girl"

**Lester Flatt

Lester Raymond Flatt (June 19, 1914 – May 11, 1979) was an American bluegrass (music), bluegrass guitarist and mandolinist, best known for his collaboration with banjo picker Earl Scruggs in the duo Flatt and Scruggs.

Flatt's career spanned ...

, 64, American bluegrass musician, died of cancer.

**Bernard Kettlewell

Henry Bernard Davis Kettlewell (24 February 1907 – 11 May 1979) was a British geneticist, lepidopterist and medical doctor, who performed research on the influence of industrial melanism on peppered moth (''Biston betularia'') coloration, sho ...

, 72, British geneticist known for Kettlewell's experiment

Kettlewell's experiment was a biological experiment in the mid-1950s to study the evolutionary mechanism of industrial melanism in the peppered moth (''Biston betularia''). It was executed by Bernard Kettlewell, working as a research fellow in the ...

of 1953 and 1955 in demonstrating the evolutionary process of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

within the fast-reproducing peppered moth

The peppered moth (''Biston betularia'') is a temperate species of Nocturnality, night-flying moth. It is mostly found in the northern hemisphere in places like Asia, Europe and North America. Peppered moth evolution is an example of populatio ...

, died of an overdose of painkillers.

** Chris Rosenberg, 28, enforcer and hitman for the Gambino crime family

The Gambino crime family (pronounced ) is an Italian American Mafia crime family and one of the "Five Families" that dominate organized crime activities in New York City, within the nationwide criminal phenomenon known as the American Mafia. ...

's DeMeo gang, was executed by his boss and friend, Roy DeMeo

Roy Albert DeMeo (; September 7, 1940 – January 10, 1983) was an American mobster in the Gambino crime family in New York City. He headed a group known as the "DeMeo crew", which consisted of approximately twenty associates involved in murder ...

to prevent a gang war.

May 12, 1979 (Saturday)

*Down 0 to 2 after 85 minutes in theFA Cup Final

The FA Cup Final is the last match in the FA Cup, Football Association Challenge Cup. It has regularly been one of the List of sports attendance figures, most attended domestic football events in the world, with an official attendance of 89,472 ...

, Manchester United

Manchester United Football Club, commonly referred to as Man United (often stylised as Man Utd) or simply United, is a professional association football, football club based in Old Trafford (area), Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, Engl ...

tied the game with two goals in the next two minutes as Gordon McQueen

Gordon McQueen (26 June 1952 – 15 June 2023) was a Scottish professional footballer who played as a centre-back for St Mirren, Leeds United and Manchester United, in addition to the Scotland national team.

McQueen started his footballing ca ...

scored at the 86th minute and Sammy McIlroy

Samuel Baxter McIlroy (born 2 August 1954) is a Northern Irish retired footballer who played for Manchester United, Stoke City, Manchester City, Örgryte (Sweden), Bury, VfB Mödling (Austria), Preston North End and the Northern Ireland na ...

in the 88th. Then, in the 89th minute, Arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

's Alan Sunderland

Alan Sunderland (born 1 July 1953) is an English former footballer who played as a forward in the Football League for Wolverhampton Wanderers, Arsenal and Ipswich Town. He was also capped once for England.

Club career

Sunderland was born in Con ...

made the winning goal.

*The Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

began construction of the Novosibirsk Metro

Novosibirsk Metro is a rapid transit system that serves Novosibirsk, Russia. The system consists of over track on two lines with 13 stations. It opened in January 1986, becoming the eleventh Metro in the USSR and the ninth in the Russian SFSR. Ac ...

, now the third busiest rapid transit system in Russia, and would have it operational within less than seven years.

*Died: Kalpana

Kalpana may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Kalpana'' (1948 film), an Indian Hindi-language dance film

* ''Kalpana'' (1960 film), a romantic Bollywood film

* ''Kalpana'' (1970 film), an Indian Malayalam film

* ''Kalpana'' (2012 film), an I ...

(stage name for Sharat Lata), 35, popular Indian Kannada language

Kannada () is a Dravidian languages, Dravidian language spoken predominantly in the state of Karnataka in southwestern India, and spoken by a minority of the population in all neighbouring states. It has 44 million native speakers, an ...

film actress, committed suicide with an overdose of barbiturates.

May 13, 1979 (Sunday)

*A group of 12 Cubans crashed a bus through the fence of the Venezuelan Embassy in Havana and were granted asylum. Venezuela refused to release the group to Cuban authorities, and the 12 Cubans remained on the embassy grounds for more than a year until being allowed to emigrate in 1980 as part of theMariel boatlift

The Mariel boatlift () was a mass emigration of Cubans who traveled from Cuba's Mariel Harbor to the United States between April 15 and October 31, 1980. The term "" is used to refer to these refugees in both Spanish and English. While the ex ...

.

* Southern Benedictine College, located in Cullman, Alabama

Cullman is the largest city and county seat of Cullman County, Alabama, United States. It is located along Interstate 65, about north of Birmingham, Alabama, Birmingham and about south of Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville. As of the 2020 United ...

, and having existed since 1953 as Saint Bernard College, ceased operations after the graduation of its final class.

*Born: Prince Carl Philip of Sweden

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The fema ...

, the oldest son of King Carl XVI Gustaf

Carl XVI Gustaf (Carl Gustaf Folke Hubertus; born 30 April 1946) is King of Sweden. Having reigned since 1973, he is the longest-reigning monarch in Swedish history.

Carl Gustaf was born during the reign of his paternal great-grandfather, K ...

and Queen Silvia, and younger brother of Crown Princess Victoria

Victoria, Crown Princess of Sweden, Duchess of Västergötland (Victoria Ingrid Alice Désirée; born 14 July 1977) is the heir apparent to the Swedish throne, as the eldest child of King Carl XVI Gustaf. If she ascends to the throne as expect ...

. Carl Philip would be heir to the throne for the first seven months of his life, but on January 1, 1980, an amendment to the Swedish Act of Succession

The 1810 Act of Succession () is one of four ''Fundamental Laws of the Realm'' () and thus forms part of the Swedish Constitution. The Act regulates the line of succession to the Swedish throne and the conditions which eligible members of the ...

changed succession to the throne from agnatic primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit all or most of their parent's estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relat ...

(the first male heir, the rule in all other monarchies) to absolute primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit all or most of their parent's estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relat ...

(the first heir, regardless of gender), making Victoria the heir apparent.

May 14, 1979 (Monday)

*Bhavnagar University

Maharaja Krishnakumarsinhji Bhavnagar University, formerly Bhavnagar University or MKBU is a state university located in Bhavnagar city in the state of Gujarat in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South ...

began its first classes after opening in the city of Bhavnagar

Bhavnagar is a city and the headquarters of Bhavnagar district in the Indian state of Gujarat. It was founded in 1723 by Bhavsinhji Gohil. It was the capital of Bhavnagar State, which was a princely state before it was merged into the Dominion ...

in the Indian state of Gujarat

Gujarat () is a States of India, state along the Western India, western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the List of states and union territories ...

.

*Died: Jean Rhys

Jean Rhys, ( ; born Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams; 24 August 1890 – 14 May 1979) was a novelist who was born and grew up in the Caribbean island of Dominica. From the age of 16, she resided mainly in England, where she was sent for her educa ...

(pen name for Ella Rees Williams), 88, English novelist

May 15, 1979 (Tuesday)

*Queen Elizabeth II opened the session of the new Parliament of the United Kingdom and, as a reporter noted, "For the first time in the country's history, both of the protagonists in the traditional ceremony were women," as the Queen read the speech written by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher for "one of the most ambitious programs presented by a new administration in Britain since the end of World War II." *Weeks after the fall of Kampala, the army ofTanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

and its Uganda National Liberation Front

The Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) was a political group formed by exiled Ugandans opposed to the rule of military dictator Idi Amin. The UNLF had an accompanying military wing, the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA). UNLA fought alo ...

allies cleared up resistance in the rest of the central African nation in the Battle of Lira

The Battle of Lira was one of the last battles in the Uganda–Tanzania War, fought by Tanzania and its Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) allies, against Uganda Army troops loyal to Idi Amin on 15 May 1979. The Tanzanian-led forces easil ...

.

*Ghanaian Air Force Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings

Jerry John Rawlings (born Jerry Rawlings John; 22 June 194712 November 2020) was a Ghanaian military officer, aviator, and politician who led the country briefly in 1979 and then from 1981 to 2001. He led a military junta until 1993 and then se ...

and six other soldiers attempted an unsuccessful coup against Ghana's president, General Fred Akuffo

Lieutenant General Frederick William "Fred" Kwasi Akuffo (21 March 1937 – 26 June 1979) was a Ghanaian soldier and politician who was the Chief of the Defence Staff of the Ghana Armed Forces from 1976 to 1978, and chairman of the ruling S ...

. The coup failed and the group were arrested, with Rawlings sentenced to death in a general court martial and imprisoned. While awaiting execution, Rawlings was sprung from custody on June 4 by a group of soldiers and carried out a second, successful coup d'état.

May 16, 1979 (Wednesday)

*The

*The Beijing Television

Beijing Radio and Television Station (BRTV), formerly Beijing Media Network (BMN), is a government-owned television network in China. It broadcasts from Beijing. The channel is available only in Chinese. Broadcasts in Beijing are on AM, FM, ca ...

(BTV), the second television network in the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, began broadcasting. As with China Central Television

China Central Television (CCTV) is the State media, national television broadcaster of China, established in 1958. CCTV is operated by the National Radio and Television Administration which reports directly to the Publicity Department of th ...

, BTV is owned by the Chinese government.

*FC Barcelona

Futbol Club Barcelona (), commonly known as FC Barcelona and colloquially as Barça (), is a professional Football club (association football), football club based in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, that competes in La Liga, the top flight of ...

of Spain beat Fortuna Düsseldorf

Düsseldorfer Turn- und Sportverein Fortuna 1895 e.V., commonly known as Fortuna Düsseldorf (), is a Football in Germany, German football club based in Düsseldorf, North Rhine-Westphalia, that competes in the 2. Bundesliga.

Founded in 1895, Fo ...

of West Germany in extra time, 4 to 3, to win the European Cup Winners' Cup

The UEFA Cup Winners' Cup was a European association football, football club competition contested annually by the winners of domestic cup competitions. The competition's official name was originally the European Cup Winners' Cup; it was renam ...

, played at Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

in Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

before a crowd of 50,000.

*Mountaineers Peter Boardman

Peter Boardman (25 December 1950 – 17 May 1982) was an English mountaineer and author. He is best known for a series of bold and lightweight expeditions to the Himalayas, often in partnership with Joe Tasker, and for his contribution to mount ...

, Doug Scott

Douglas Keith Scott (29 May 19417 December 2020) was an English Mountaineering, mountaineer and climbing author, noted for being on the team that made the 1975 British Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition, first ascent of the south-west fac ...

and Joe Tasker

Joe Tasker (12 May 1948 – 17 May 1982) was a British Climbing, climber, active during the late 1970s and early 1980s. He died while climbing Mount Everest.

Early life

Born into a Roman Catholic family in 1948, Tasker was the second of ten ...

became the first people to ascend the steep North Ridge of the third-highest mountain in the world, to reach the summit of the high Kangchenjunga

Kangchenjunga is the third-highest mountain in the world. Its summit lies at in a section of the Himalayas, the ''Kangchenjunga Himal'', which is bounded in the west by the Tamur River, in the north by the Lhonak River and Jongsang La, and ...

.

*Died:

**A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American-led labor union. In the ...

, 90, African-American civil rights leader who organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Founded in 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids (commonly referred to as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, BSCP) was the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation o ...

labor union in 1925 and the March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (commonly known as the March on Washington or the Great March on Washington) was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

in 1963, as well as successfully lobbying U.S. Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman for executive orders banning racial discrimination in the defense industries (in 1941) and ending racial segregation in the U.S. armed services (in 1948).

** Kampatimar Shankariya, 27, Indian serial killer responsible for more than 70 murders in a little more than a year in 1977 and 1978, committed by striking the victim with a hammer blow to the neck, was hanged at the prison in Jaipur

Jaipur (; , ) is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the List of cities and towns in Rajasthan, largest city of the north-western States and union territories of India, Indian state of Rajasthan. , the city had ...

May 17, 1979 (Thursday)

*In one of the highest scoring major league baseball games of the 20th century, in which the score was 7 to 6 after the first inning, thePhiladelphia Phillies

The Philadelphia Phillies are an American professional baseball team based in Philadelphia. The Phillies compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) East Division. Since 2004, the team's home stadium has ...

defeated the Chicago Cubs

The Chicago Cubs are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The Cubs compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (baseball), National League (NL) National League Central, Central Division. Th ...

, 23 to 22 at Wrigley Field

Wrigley Field is a ballpark on the North Side, Chicago, North Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is the home ballpark of Major League Baseball's Chicago Cubs, one of the city's two MLB franchises. It first opened in 1914 as Weeghman Park for Charl ...

in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

. The highest-ever scoring game, coincidentally, took place at Wrigley Field between the same two teams on August 25, 1922, when the Chicago Cubs

The Chicago Cubs are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The Cubs compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (baseball), National League (NL) National League Central, Central Division. Th ...

beat the Philadelphia Phillies

The Philadelphia Phillies are an American professional baseball team based in Philadelphia. The Phillies compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) East Division. Since 2004, the team's home stadium has ...

, 26 to 23.

May 18, 1979 (Friday)

*A U.S. District Court jury awarded the family of the lateKaren Silkwood

Karen Gay Silkwood (February 19, 1946 – November 13, 1974) was an American laboratory technician and labor union activist known for reporting concerns about corporate practices related to health and safety in a nuclear facility.

She ...

$505,000 in compensatory damages and $10,000,000 in punitive damages to be paid by the Kerr-McGee company for her negligent radiation poisoning from plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

, in a lawsuit suit filed under the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 is a US labor law governing the federal law of occupational health and safety in the private sector and federal government in the United States. It was enacted by Congress in 1970 and was signed b ...

. The award would be reduced on appeal to only $5,000 damages, but the U.S. Supreme Court would overturn the appellate court ruling; the Silkwood family would eventually settle with Kerr-McGee for $1,380,000.

*In the divided island nation of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, the Greek Cypriot President, Spyros Kyprianou

Spyros Achilleos Kyprianou (; 28 October 1932 – 12 March 2002) was a Cypriot barrister and politician, who served as President of Cyprus from 1977 to 1988. He also served as President of the Cypriot House of Representatives from 1976 to 19 ...

conferred with Rauf Denktash Rauf or Rawuf (Arabic: رَؤُوف ''ra’ūf'' or ''rawūf'') is an Arabic male given name or surname which is a noun and the exaggerated form of the name Raif (or Raef) meaning "kind, affectionate, benign", "sympathetic, merciful" or ''compassio ...

, leader of the breakaway Turkish Cypriot state in northern Cyprus. The two halves of Cyprus had been separated since a civil war in 1974.

*After 12 Texas State Senators went into hiding to prevent the state senate from having a quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a group necessary to constitute the group at a meeting. In a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature), a quorum is necessary to conduct the business of ...

for a vote on a Republican proposal to allow registered voters of one party to vote in another party's presidential primary, Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby (in his capacity as state senate president) ordered their arrest so that the absent legislators would be compelled to appear for a session. After a five-day absence, the "Killer Bees" (Hobby's nickname for the group) emerged from hiding and appeared at the senate chamber in Austin

Austin refers to:

Common meanings

* Austin, Texas, United States, a city

* Austin (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin Motor Company, a British car manufac ...

and had brought enough attention to the legislation to prevent its passage.

May 19, 1979 (Saturday)

*The price of a gallon of gasoline reached onepound sterling

Sterling (symbol: £; currency code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound is the main unit of sterling, and the word '' pound'' is also used to refer to the British currency general ...

for the first time in British history, as the Price Commission reported that the price at some Esso

Esso () is a trading name for ExxonMobil. Originally, the name was primarily used by its predecessor Standard Oil of New Jersey after the breakup of the original Standard Oil company in 1911. The company adopted the name "Esso" (from the phon ...

petrol stations was £1.02, although most other stations had prices ranging from 89p to 92p per gallon.

*The Philadelphia Phillies

The Philadelphia Phillies are an American professional baseball team based in Philadelphia. The Phillies compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) East Division. Since 2004, the team's home stadium has ...

U.S. baseball team unveiled its "Saturday Night Special" home uniform, all-burgundy version with white trimmings, to be worn for Saturday games. They were worn only once, in a 10–5 loss to the Montreal Expos. The immediate reaction of the media, fans, and players alike was negative, with many describing the despised uniforms as pajama-like. As such, the idea was hastily abandoned.

*Born: Kamran Najafzadeh, Iranian TV journalist and presenter, in Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

May 20, 1979 (Sunday)

*TheWorld Hockey Association

The World Hockey Association () was a professional ice hockey major league that operated in North America from 1972–73 WHA season, 1972 to 1978–79 WHA season, 1979. It was the first major league to compete with the National Hockey League (N ...

played its final game. The Winnipeg Jets

The Winnipeg Jets are a professional ice hockey team based in Winnipeg. The Jets compete in the National Hockey League (NHL) as a member of the Central Division (NHL), Central Division in the Western Conference (NHL), Western Conference. The te ...

won Game 6 of the last Avco Cup for the WHA championship, beating the Edmonton Oilers

The Edmonton Oilers are a professional ice hockey team based in Edmonton. The Oilers compete in the National Hockey League (NHL) as a member of the Pacific Division (NHL), Pacific Division in the Western Conference (NHL), Western Conference. Th ...

, 7 to 3, at home to win the series, 4 games to 2. Dave Semenko

David John Semenko (July 12, 1957 – June 29, 2017) was a Canadian professional ice hockey player, coach, scout, and colour commentator. During his National Hockey League (NHL) career, Semenko played for the Edmonton Oilers, Hartford Whalers an ...

of Edmonton scored the final WHA goal. The Jets and the Oilers, along with the Quebec Nordiques

The Quebec Nordiques (, pronounced in Quebec French, in Canadian English; translated "Northmen" or "Northerners") were a professional ice hockey team based in Quebec City. The Nordiques played in the World Hockey Association (1972–1979) an ...

and the New England Whalers

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

** "New" (Paul McCartney song), 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, 1995

* "New" (Daya song), 2017

* "New" (No Doubt song), 1 ...

would join the National Hockey League

The National Hockey League (NHL; , ''LNH'') is a professional ice hockey league in North America composed of 32 teams25 in the United States and 7 in Canada. The NHL is one of the major professional sports leagues in the United States and Cana ...

at the start of the 1979–80 NHL season

The 1979–80 NHL season was the 63rd season of the National Hockey League. This season saw the addition of four teams from the disbanded World Hockey Association as expansion franchises. The Edmonton Oilers, Winnipeg Jets, New England Whalers ...

.

May 21, 1979 (Monday)

*FormerSan Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

city council member Dan White

Daniel James White (September 2, 1946 – October 21, 1985) was an American politician who assassinated George Moscone, the 37th mayor of San Francisco, and Harvey Milk, a fellow member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, inside San ...