Maures on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The term Moor is an

The term Moor is an

As it was Muslim Berbers and Arabs who conquered the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa in 711, the word has been applied to the inhabitants of the peninsula under Muslim rule (known in this context as

As it was Muslim Berbers and Arabs who conquered the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa in 711, the word has been applied to the inhabitants of the peninsula under Muslim rule (known in this context as

The "Moors" of West Africa and the Beginnings of the Portuguese Slave Trade

Published from Pomona Faculty Publications and Research from Claremont Colleges

a

Othello's Predecessors: Moors in Renaissance Popular Literature

(outline).

exonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

used in European languages to designate the Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

populations of North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

(the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

) and the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

(particularly al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

) during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

.

Moors are not a single, distinct or self-defined people. Europeans of the Middle Ages and the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

variously applied the name to Arabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

, Berbers

Berbers, or the Berber peoples, also known as Amazigh or Imazighen, are a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa who predate the arrival of Arab migrations to the Maghreb, Arabs in the Maghreb. Their main connec ...

, and Muslim Europeans. The term has been used in a broader sense to refer to Muslims in general,Menocal, María Rosa (2002). ''Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain''. Little, Brown, & Co. , p. 241 especially those of Arab or Berber descent, whether living in al-Andalus or North Africa. The 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'' observed that the term had "no real ethnological

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural anthropology, cultural, social anthropology, so ...

value." The word has racial connotations and it has fallen out of fashion among scholars since the mid-20th century.

The word is also used when denoting various other specific ethnic groups in western Africa and some parts of Asia. During the colonial era, the Portuguese introduced the names " Ceylon Moors" and "Indian Moors

Indian Moors were a grouping of people who existed in Sri Lanka predominantly during its colonial period. They were distinguished by their Muslim faith whose origins traced back to the British Raj. Therefore, Indian Moors refer to a number of eth ...

" in South Asia and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, now official ethnic designations on the island nation, and the Bengali Muslims

Bengali Muslims (; ) 'Mussalman'' also used in this work.are adherents of Islam who ethnically, linguistically and genealogically identify as Bengalis. Comprising over 70% of the global Bengali population, they are the second-largest et ...

were also called Moors. In the Philippines, the longstanding Muslim community, which predates the arrival of the Spanish, now self-identifies as the "Moro people

The Moro people or Bangsamoro people are the 13 Muslim-majority ethnolinguistic Austronesian groups of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan, native to the region known as the Bangsamoro (lit. ''Moro nation'' or ''Moro country''). As Muslim-majority ...

", an exonym introduced by Spanish colonizers due to their Muslim faith.

Etymology

The etymology of the word "Moor" is uncertain, although it can be traced back to the Phoenician term ''Mahurin'', meaning "Westerners". From ''Mahurin'', theancient Greeks

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically re ...

derive ''Mauro'', from which Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

derives ''Mauri

Mauri (from which derives the English term "Moors") was the Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, located in the west side of North Africa on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesarien ...

''. The word "Moor" is presumably of Phoenician origin. Some sources attribute a Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

origin to the word.

Historical usage

Antiquity

During the classical period, the Romans interacted with, and later conquered, parts ofMauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It extended from central present-day Algeria to the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, encompassing northern present-day Morocco, and from the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean in the ...

, a state that covered modern northern Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, western Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, and the Spanish cities Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ) is an Autonomous communities of Spain#Autonomous cities, autonomous city of Spain on the North African coast. Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Ceuta is one of th ...

and Melilla

Melilla (, ; ) is an autonomous city of Spain on the North African coast. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of . It was part of the Province of Málaga un ...

. The Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

tribes of the region were noted in the Classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

as ''Mauri

Mauri (from which derives the English term "Moors") was the Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, located in the west side of North Africa on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesarien ...

'', which was subsequently rendered as "Moors" in English and in related variations in other European languages. ''Mauri'' (Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: Μαῦροι) is recorded as the native name by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

in the early 1st century. This appellation was also adopted into Latin, whereas the Greek name for the tribe was ''Maurusii'' (). The Moors were also mentioned by Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical works, ''Annals'' ( ...

as having revolted against the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

in 24 AD.

Medieval and early modern Europe

During the LatinMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, ''Mauri'' was used to refer to Berbers and Arabs in the coastal regions of Northwest Africa. The 16th century scholar Leo Africanus

Johannes Leo Africanus (born al-Ḥasan ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Wazzān al-Zayyātī al-Fasī, ; – ) was an Andalusi diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book '' Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later publish ...

(c. 1494–1554) identified the Moors (''Mauri'') as the native Berber inhabitants of the former Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

Africa Province

Africa was a Roman province on the northern coast of the continent of Africa. It was established in 146 BC, following the Roman Republic's conquest of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisi ...

( Roman Africans).

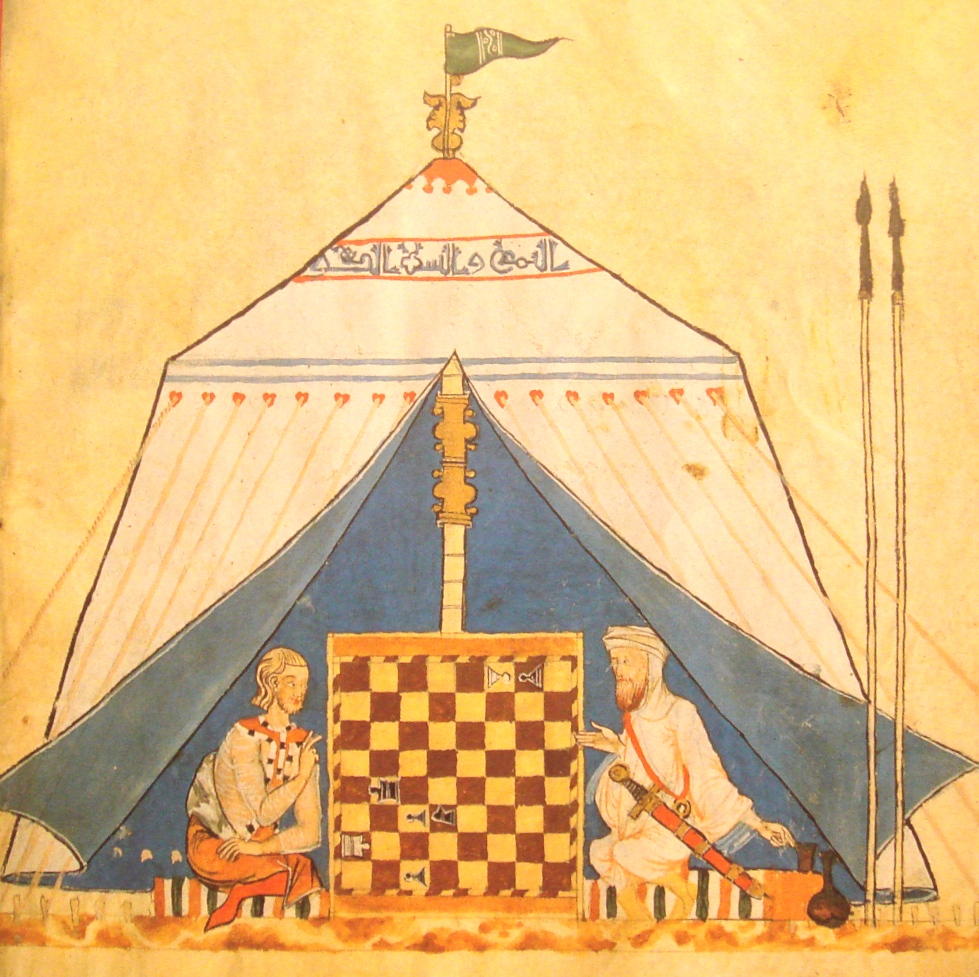

As it was Muslim Berbers and Arabs who conquered the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa in 711, the word has been applied to the inhabitants of the peninsula under Muslim rule (known in this context as

As it was Muslim Berbers and Arabs who conquered the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa in 711, the word has been applied to the inhabitants of the peninsula under Muslim rule (known in this context as al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

). The term could also be applied to the Muslims of Sicily, who began to arrive there during the Aghlabid conquest of the 9th century. The word passed into Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian as ''Moros'' or other cognates

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the soun ...

. The Emirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada, also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, was an Emirate, Islamic polity in the southern Iberian Peninsula during the Late Middle Ages, ruled by the Nasrid dynasty. It was the last independent Muslim state in Western ...

, the last Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula, was conquered by the Spanish in 1492, resulting in all remaining Muslims in this area to pass under Christian rule. These Muslims and their descendants were thereafter known as ''Moriscos

''Moriscos'' (, ; ; " Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Catholic Church and Habsburg Spain commanded to forcibly convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed Islam. Spain had a sizeable M ...

'' ('Moorish' or 'Moor-like') up until their final expulsion from Spain Expulsion from Spain may refer to:

* Expulsion of Jews from Spain (1492 in Aragon and Castile, 1497–98 in Navarre)

* Expulsion of the Moriscos (1609–1614)

See also

* Forced conversions of Muslims in Spain (1500–1502 in Castile, 1515–16 ...

in 1609.

The word was more commonly also a racial term for dark-skinned or black people, which is the meaning with which it also passed into English as early as the 14th century. In medieval European literature, the term often denotes Muslim foes of Christian Europe in a derogatory manner. During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, it became associated with more romanticized depictions, even when Muslims were otherwise depicted negatively. In works of this period, the "Moor" may appear as a courageous warrior, a sexually overt personality, or other stereotypes. Examples of such characters are found in the Spanish ''Poem of the Cid

''El Cantar de mio Cid'', or ''El Poema de mio Cid'' ("The Song of My Cid"; "The Poem of My Cid"), is an anonymous '' cantar de gesta'' and the oldest preserved Castilian epic poem. Based on a true story, it tells of the deeds of the Castilian h ...

'' and in Shakespeare's ''Othello

''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'', often shortened to ''Othello'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare around 1603. Set in Venice and Cyprus, the play depicts the Moorish military commander Othello as he is manipulat ...

.''

Since the early modern period, "Moors" or "Moorish" has also been used by western historians and scholars to refer to the history and heterogeneous people of Islamic North Africa and al-Andalus. Since the mid-20th century, however, this usage has declined, though it sometimes persists to denote related topics, such as "Moorish" architecture. The word otherwise retains some racial connotations.

'White Moors' and 'Black Moors'

The existence of both 'white Moors' and 'black Moors' is attested in historical literature from the late Middle Ages onwards. These terms are still used in modern-dayMauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

, where the Moorish population is divided into the socially dominant 'white Moors' of Berber and Arab origin (also known '' Beidanes''), and 'black Moors' (also known as '' Haratines'') who are former slaves''.''

In the 1453 chronicle ''The Discovery and Conquest of Guinea'' the Portuguese chronicler Gomes Eannes de Azurara writes: "Dinis Diaz, leaving Portugal with his company, never lowered sail till he had passed the land of the Moors and arrived in the land of the blacks, that is called Guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

." The 'land of the blacks' here refers to the regions south of the Sahara known as ''bilād as-sūdān'' in Medieval Arabic texts. De Azurara also notes the existence of 'blacks' among the Moors, stating that "these blacks were Moors like the others, though their slaves, in accordance with ancient custom". In ''The First Book of the Introduction of Knowledge'' (1542) the English author Andrew Borde writes that "Barbary

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

is a great country, and plentiful of fruit, wine and corn. The inhabitants be called the Moors; there be white Moors and black Moors; they be infidels and unchristened." Borde includes a poem about "a black Moor born in Barbary" who will be "a good diligent slave". In his ''Description of Africa'' (1550) The Andalusi author Leo Africanus

Johannes Leo Africanus (born al-Ḥasan ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Wazzān al-Zayyātī al-Fasī, ; – ) was an Andalusi diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book '' Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later publish ...

- described as a Moor by the English translator John Pory (1600) - refers to the Berber populations of Barbary

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

and Numidia

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

as "white Africans", translated by Pory as "white or tawny Moors".

Modern meanings

Apart from its historic associations and context, ''Moor'' and ''Moorish'' designate a specific ethnic group speakingHassaniya Arabic

Hassaniya Arabic (; also known as , , , , and Maure) is a variety of Maghrebi Arabic spoken by Mauritanian Arabs, Malian Arabs and the Sahrawis. It was spoken by the Beni Ḥassān Bedouin tribes of Yemeni origin who extended their authority o ...

. They inhabit Mauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

and parts of Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, Western Sahara

Western Sahara is a territorial dispute, disputed territory in Maghreb, North-western Africa. It has a surface area of . Approximately 30% of the territory () is controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR); the remaining 70% is ...

, Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

, Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

, and Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

. In Niger and Mali, these peoples are also known as the Azawagh Arabs, after the Azawagh region of the Sahara.

The authoritative dictionary of the Spanish language does not list any derogatory meaning for the word ''moro'', a term generally referring to people of Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

ian origin in particular or Muslims in general. Some authors have pointed out that in modern colloquial Spanish use of the term ''moro'' is derogatory for Moroccans

Moroccans () are the Moroccan nationality law, citizens and nationals of the Morocco, Kingdom of Morocco. The country's population is predominantly composed of Arabs and Berbers (Amazigh). The term also applies more broadly to any people who ...

in particular.

In the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, a former Spanish colony, many modern Filipinos

Filipinos () are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. Filipinos come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino language, Filipino, Philippine English, English, or other Philippine language ...

call the large, local Muslim minority concentrated in Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) is the List of islands of the Philippines, second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and List of islands by population, seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the ...

and other southern islands ''Moros

In Greek mythology, Moros /ˈmɔːrɒs/ or Morus /ˈmɔːrəs/ (Ancient Greek: Μόρος means 'doom, fate') is the personified spirit of impending doom, who drives mortals to their deadly fate. It was also said that Moros gave people the abi ...

''. The word is a catch-all term, as ''Moro'' may come from several distinct ethno-linguistic groups such as the Maranao people

The Maranao people (Maranao language, Maranao: ''Bangsa'' ''Mëranaw''; Filipino language, Filipino: ''mga'' ''Maranaw''), also spelled Meranaw, Maranaw, and Mëranaw, is a predominantly Muslim Filipino people, Filipino ethnic groups of the ...

. The term was introduced by Spanish colonisers, and has since been appropriated by Filipino Muslims as an endonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

, with many self-identifying as members of the ''Bangsamoro'' "Moro Nation".

''Moreno

Moreno may refer to:

Places Argentina

* Moreno (Buenos Aires Metro), a station on Line C of the Buenos Aires Metro

*Moreno, Buenos Aires, a city in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

* Moreno Department, a depatnent of Santiago del Estero Province, ...

'' can mean "dark-skinned" in Spain, Portugal, Brazil, and the Philippines. Also in Spanish, ''morapio'' is a humorous name for "wine", especially that which has not been "baptized" or mixed with water, i.e., pure unadulterated wine. Among Spanish speakers, ''moro'' came to have a broader meaning, applied to both Filipino Moros from Mindanao, and the morisco

''Moriscos'' (, ; ; "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Catholic Church and Habsburg Spain commanded to forcibly convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed Islam. Spain had a sizeable Mus ...

s of Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

. ''Moro'' refers to all things dark, as in "Moor", ''moreno'', etc. It was also used as a nickname; for instance, the Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

ese Duke Ludovico Sforza

Ludovico Maria Sforza (; 27 July 1452 – 27 May 1508), also known as Ludovico il Moro (; 'the Moor'), and called the "arbiter of Italy" by historian Francesco Guicciardini,

was called ''Il Moro'' because of his dark complexion.

In Portugal, ''mouro'' (feminine,'' moura'') may refer to supernatural beings known as enchanted ''moura'', where "Moor" implies "alien" and "non-Christian". These beings were siren-like fairies with golden or reddish hair and a fair face. They were believed to have magical properties. From this root, the name moor is applied to unbaptized children, meaning not Christian. In Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, '' mairu'' means moor and also refers to a mythical people.

Muslims located in South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

were distinguished by the Portuguese historians into two groups: Mouros da Terra ("Moors of the Land") and the Mouros da Arabia/Mouros de Meca ("Moors from Arabia/Mecca" or "Paradesi Muslims").Subrahmanyam, Sanjay."The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500-1650" Cambridge University Press, (2002) The Mouros da Terra were either descendants of any native convert (mostly from any of the former lower or untouchable castes) to Islam or descendants of a marriage alliance between a Middle Eastern individual and an Indian woman.

Within the context of Portuguese colonization

Portuguese maritime explorations resulted in numerous territories and maritime routes recorded by the Portuguese on journeys during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of European exploration, chronicling and mapp ...

, in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

(Portuguese Ceylon

Portuguese Ceylon (; ; ) is the name given to the territory on Ceylon, modern-day Sri Lanka, controlled by the Portuguese Empire between 1597 and 1658.

Portuguese presence in the island lasted from 1505 to 1658. Their arrival was largely accide ...

), Muslims of Arab origin are called ''Ceylon Moors'', not to be confused with "Indian Moors" of Sri Lanka (see Sri Lankan Moors

Sri Lankan Moors (; Arwi: ; ; formerly Ceylon Moors; colloquially referred to as Sri Lankan Muslims) are an ethnic minority group in Sri Lanka, comprising 9.3% of the country's total population. Most of them are native speakers of the Tamil langua ...

). Sri Lankan Moors (a combination of "Ceylon Moors" and "Indian Moors") make up 12% of the population. The Ceylon Moors (unlike the Indian Moors) are descendants of Arab traders who settled there in the mid-6th century. When the Portuguese arrived in the early 16th century, they labelled all the Muslims in the island as Moors as they saw some of them resembling the Moors in North Africa. The Sri Lankan government continues to identify the Muslims in Sri Lanka as "Sri Lankan Moors", sub-categorised into "Ceylon Moors" and "Indian Moors".

The Goan Muslims—a minority community who follow Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

in the western India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n coastal state of Goa

Goa (; ; ) is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is bound by the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north, and Karnataka to the ...

—are commonly referred as ''Moir'' () by Goan Catholics

Goan Catholics () are an Ethnoreligious group, ethno-religious community adhering to the Latin Church, Latin Rite of the Catholic Church from the Goa state, in the southern part of the Konkan region along the west coast of India. They are Konka ...

and Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

s. ''Moir'' is derived from the Portuguese word ''mouro'' ("Moor").

In heraldry

Moors—or more frequently their heads, often crowned—appear with some frequency in medieval Europeanheraldry

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, Imperial, royal and noble ranks, rank and genealo ...

, though less so since the Middle Ages. The term ascribed to them in Anglo-Norman ''blazon

In heraldry and heraldic vexillology, a blazon is a formal description of a coat of arms, flag or similar emblem, from which the reader can reconstruct an accurate image. The verb ''to blazon'' means to create such a description. The visual d ...

'' (the language of English heraldry

English heraldry is the form of coats of arms and other heraldic bearings and insignia used in England. It lies within the so-called Gallo-British tradition. Coats of arms in England are regulated and granted to individuals by the English kings ...

) is ''maure'', though they are also sometimes called ''moore'', ''blackmoor'', '' blackamoor'' or ''negro''. Maure

A Moor's head, also known as a Maure, since the 11th century, is a symbol depicting the head of a black moor. The term moor came to define anyone who was African and Muslim.

Origin

The precise origin of the Moor's head as a heraldic symbol is ...

s appear in European heraldry from at least as early as the 13th century, and some have been attested as early as the 11th century in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, where they have persisted in the local heraldry

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, Imperial, royal and noble ranks, rank and genealo ...

and vexillology

Vexillology ( ) is the study of the history, symbolism and usage of flags or, by extension, any interest in flags in general.Smith, Whitney. ''Flags Through the Ages and Across the World'' New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975. Print.

A person who studi ...

well into modern times in Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

.

Armigers bearing moors or moors' heads may have adopted them for any of several reasons, to include symbolizing military victories in the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

, as a pun on the bearer's name in the canting arms

Canting arms are heraldry, heraldic bearings that represent the bearer's name (or, less often, some attribute or function) in a visual pun or rebus.

The expression derives from the latin ''cantare'' (to sing).

French heralds used the term (), ...

of Morese, Negri, Saraceni, etc., or in the case of Frederick II, possibly to demonstrate the reach of his empire. The arms of Pope Benedict XVI feature a moor's head, crowned and collared red, in reference to the arms of Freising, Germany. In the case of Corsica and Sardinia, the blindfolded moors' heads in the four quarters have long been said to represent the four Moorish emirs who were defeated by Peter I of Aragon and Pamplona

Peter I (, , ; 1068 – 1104) was King of Aragon and also Pamplona from 1094 until his death in 1104. Peter was the eldest son of Sancho Ramírez, from whom he inherited the crowns of Aragon and Pamplona, and Isabella of Urgell. He was named i ...

in the 11th century, the four moors' heads around a cross having been adopted to the arms of Aragon around 1281–1387, and Corsica and Sardinia having come under the dominion of the king of Aragon in 1297. In Corsica, the blindfolds were lifted to the brow in the 18th century as a way of expressing the island's newfound independence.

The use of Moors (and particularly their heads) as a heraldic symbol has been deprecated in modern North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. For example, the College of Arms of the Society for Creative Anachronism

The Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA) is an international living history group with the aim of studying and recreating mainly Medieval European cultures and their histories before the 17th century. A quip often used within the SCA describes ...

urges applicants to use them delicately to avoid causing offence.

See also

*Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

* Mohammedan

''Mohammedan'' (also spelled ''Muhammadan'', ''Mahommedan'', ''Mahomedan'' or ''Mahometan'') is a term for a follower of Muhammad, the Islamic prophet. It is used as both a noun and an adjective, meaning belonging or relating to, either Muhamm ...

* Turk (term for Muslims)

The ethnonym Turks (/''Tourkoi'', /, ) has been commonly used by the non-Muslim Balkan peoples to denote all Muslim settlers in the region, regardless of their ethno-linguistic background. Most of them, however, were indeed ethnic Turks. In the Ot ...

* Böszörmény

Böszörmény, also Izmaelita or Hysmaelita ("Ishmaelites") or Szerecsen ("Saracens"), is a name for the Muslims who lived in Hungary from its foundation at the end of the 9th century until the end of the 13th century. The ''Böszörmény'' were a ...

* Genetic history of the Iberian Peninsula

The ancestry of modern Iberians (comprising the Spaniards, Spanish and Portuguese people, Portuguese) is consistent with the geographical situation of the Iberian Peninsula in the South-west corner of Europe, showing characteristics that are lar ...

* Genetic studies on Moroccans

* Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

* Ricote (''Don Quixote'')

Notes

*...''Hindu Kristao Moir sogle bhau''- Hindus, Christians and Muslims are all brothers...References

External links

The "Moors" of West Africa and the Beginnings of the Portuguese Slave Trade

Published from Pomona Faculty Publications and Research from Claremont Colleges

a

PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

article.

* Sean Cavazos-KottkeOthello's Predecessors: Moors in Renaissance Popular Literature

(outline).

Folger Shakespeare Library

The Folger Shakespeare Library is an independent research library on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., United States. It has the world's largest collection of the printed works of William Shakespeare, and is a primary repository for rare materia ...

, 1998.

{{Authority control

Exonyms

Al-Andalus

Arab people

Arabs in Portugal

Arabs in Spain

Berbers

Berbers in Portugal

Berbers in Spain