Matthew Stirling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Matthew Williams Stirling (August 28, 1896 – January 23, 1975) was an American

In 1931, he met Marion Illig (1911–2001), who took a job as his secretary. They married on December 11, 1933 and worked together for the next forty-two years, until his death. She accompanied him on all but one of his subsequent archaeological expeditions. They had a son and a daughter. Matthew Stirling wrote that Marion was his "co-explorer, co-author and general co-ordinator."

Stirling was intrigued by Marshall Saville's two 1929 reports, ''Votive Axes from Ancient Mexico''. Subsequent discussions with Saville launched Stirling into a phase of his career which would be focused on what was then beginning to be called Olmec culture.

In 1931, he met Marion Illig (1911–2001), who took a job as his secretary. They married on December 11, 1933 and worked together for the next forty-two years, until his death. She accompanied him on all but one of his subsequent archaeological expeditions. They had a son and a daughter. Matthew Stirling wrote that Marion was his "co-explorer, co-author and general co-ordinator."

Stirling was intrigued by Marshall Saville's two 1929 reports, ''Votive Axes from Ancient Mexico''. Subsequent discussions with Saville launched Stirling into a phase of his career which would be focused on what was then beginning to be called Olmec culture.

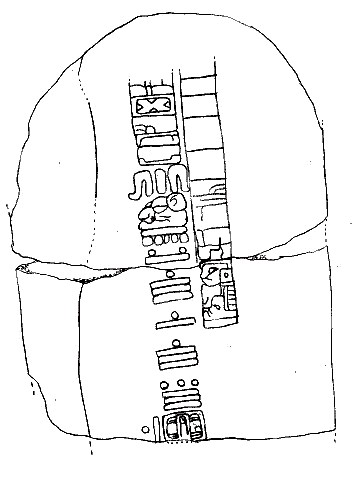

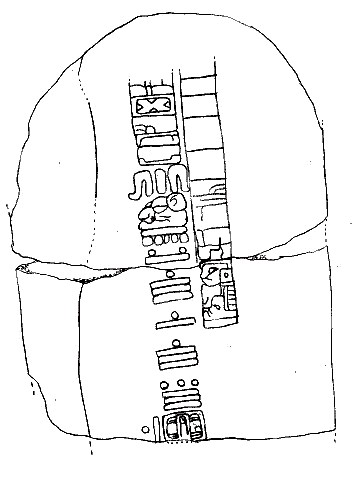

During excavations there in 1939, they discovered Stela C. The top half of the monument was missing but the bottom half produced a Long Count date of ?.16.6.16.18. If the first digit was a "7" then the date would correlate to 32 BCE, a date considered by many to be too early for a

During excavations there in 1939, they discovered Stela C. The top half of the monument was missing but the bottom half produced a Long Count date of ?.16.6.16.18. If the first digit was a "7" then the date would correlate to 32 BCE, a date considered by many to be too early for a

The Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec

* ttp://www.latinamericanstudies.org/stirling.htm The Latin American Studies' Stirling Page {{DEFAULTSORT:Stirling, Matthew Williams American ethnologists American Mesoamericanists Mesoamerican archaeologists Olmec scholars Smithsonian Institution people Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni American Episcopalians 1896 births 1975 deaths 20th-century Mesoamericanists 20th-century American archaeologists

ethnologist

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).

Scien ...

, archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

and later an administrator at several scientific institutions in the field. He is best known for his discoveries relating to the Olmec

The Olmecs () or Olmec were an early known major Mesoamerican civilization, flourishing in the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco from roughly 1200 to 400 Before the Common Era, BCE during Mesoamerica's Mesoamerican chronolog ...

civilization.

Much of his work was done with his "wife and constant collaborator" of 42 years Marion Stirling

Marion Stirling Pugh ( Illig, May 12, 1911 – April 24, 2001) was an American archaeologist. She is known for her archaeological expeditions to Tres Zapotes and other sites in Southern Mexico in the 1940s, conducted alongside her husband Matthe ...

(nee Illig, later Pugh).

Stirling began his career with extensive ethnological work in the United States, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

and Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

, before directing his attention to the Olmec civilization and its possible primacy among the pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

societies of Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

. His discovery of, and excavations at, various sites attributed to Olmec culture in the Mexican Gulf Coast region significantly contributed towards a better understanding of the Olmecs and their culture. He then began investigating links between the different civilizations in the region. Apart from his extensive field work and publications, later in his career Stirling proved to be an able administrator of academic and research bodies, who served on directorship boards of a number of scientific organizations.

Early life and work

Matthew was born in Salinas,California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, where his father managed the Southern Pacific Milling Company. Most of his childhood days were spent on his grandfather's ranch where he first developed an interest in antiquity, collecting arrowheads and researching artefacts.

Stirling majored in anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

under Alfred L. Kroeber, graduating from the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university, research university system in the U.S. state of California. Headquartered in Oakland, California, Oakland, the system is co ...

in 1920. His interest in the Olmecs began in about 1918, when he saw a picture of a "crying-baby" blue jade masquette, published by Thomas Wilson of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in 1898. When he traveled to Europe with his family after graduation, he found the masquette itself in the Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

Museum, and intrigued by the Olmec culture, took time to look at other specimens in the Maximilian Collection in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, and later, in Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

.

Stirling was a teaching fellow at the University of California during 1920–21. He then joined the Smithsonian Institution, as a museum aide and assistant curator in its Division of Ethnology at the National Museum. He worked there until 1925. He located several more Olmec pieces in the museum. During this period, he also obtained his master's degree in Anthropology from the George Washington University

The George Washington University (GW or GWU) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally-chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Originally named Columbian College, it was chartered in 1821 by ...

. He was later, in 1943, to receive a Doctorate in Science from Tampa University.

He excavated on Weedon Island for the Bureau of American Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology (or BAE, originally, Bureau of Ethnology) was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Departme ...

(BAE) in 1923–24, and at Arikara

The Arikara ( ), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

villages in Mobridge, ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

, during the summer of 1924. Stirling resigned from the Smithsonian to lead a 400-member, Smithsonian Institution-Dutch Colonial Government, expedition to New Guinea in 1925. He conducted ethnological and physical anthropological studies among the indigenous peoples there, and collected a number of natural history specimens, which now form one of the most valuable collections in the National Museum.

He returned to take over as chief of the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnology in 1928. He retained the position until 1957, his title changing to director in 1947. He went to Ecuador in 1931–32, conducting ethnological studies of the Jívaro, as part of Donald C. Beatty's expedition. He also worked along the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South or the South Coast, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Tex ...

, directing archaeological digs in Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

.

In 1931, he met Marion Illig (1911–2001), who took a job as his secretary. They married on December 11, 1933 and worked together for the next forty-two years, until his death. She accompanied him on all but one of his subsequent archaeological expeditions. They had a son and a daughter. Matthew Stirling wrote that Marion was his "co-explorer, co-author and general co-ordinator."

Stirling was intrigued by Marshall Saville's two 1929 reports, ''Votive Axes from Ancient Mexico''. Subsequent discussions with Saville launched Stirling into a phase of his career which would be focused on what was then beginning to be called Olmec culture.

In 1931, he met Marion Illig (1911–2001), who took a job as his secretary. They married on December 11, 1933 and worked together for the next forty-two years, until his death. She accompanied him on all but one of his subsequent archaeological expeditions. They had a son and a daughter. Matthew Stirling wrote that Marion was his "co-explorer, co-author and general co-ordinator."

Stirling was intrigued by Marshall Saville's two 1929 reports, ''Votive Axes from Ancient Mexico''. Subsequent discussions with Saville launched Stirling into a phase of his career which would be focused on what was then beginning to be called Olmec culture.

The Olmec

The Olmec were an ancient Pre-Columbian people living in south-centralMexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, in the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco, from about 1200 BCE to 400 BCE. They are claimed by many to be the mother culture of every primary element common to later Mesoamerican civilizations.

The name "Olmec" means "rubber people" in Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

, the language of the Aztecs. It was the Aztec name for the people who lived in this area at the time of Aztec dominance, referring to them as those who supplied the rubber balls used for games. Early modern explorers applied the name "Olmec" to ruins and art from this area before it was understood that these had been already abandoned more than a thousand years before the time of the people the Aztecs knew as the "Olmec".

Stirling and history of the Olmecs

By 1929, Stirling had begun suspecting that the artifacts emerging out of Mexico belonged to a time much earlier than attributed to the Olmecs. From the BAE, he directed excavations in fringes of the area thought to beMaya

Maya may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Mayan languages, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (East Africa), a p ...

. Matthew and Marion Stirling first visited Tres Zapotes in 1938. They travelled to the western margin and concentrated on the Tres Zapotes

Tres Zapotes is a Mesoamerican archaeological site located in the south-central Gulf Lowlands of Mexico in the Papaloapan River plain. Tres Zapotes is sometimes referred to as the third major Olmec capital (after San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán and La ...

site. He noted the position of the colossal head – surrounded by four mounds – and the presence of a vast mound group in the area. He interested the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

enough to be granted funds for excavation. This began a sixteen-year association with the site.

During excavations there in 1939, they discovered Stela C. The top half of the monument was missing but the bottom half produced a Long Count date of ?.16.6.16.18. If the first digit was a "7" then the date would correlate to 32 BCE, a date considered by many to be too early for a

During excavations there in 1939, they discovered Stela C. The top half of the monument was missing but the bottom half produced a Long Count date of ?.16.6.16.18. If the first digit was a "7" then the date would correlate to 32 BCE, a date considered by many to be too early for a Mesoamerican

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

civilization. An "8" would mean a date of 363 CE. The Stirlings opted for the earlier date, to the consternation of many in the archaeological community.

They were proven correct in 1970, when the top half of Stela

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

C was discovered, and the earlier date of 7.16.6.16.18, or 32 BCE, was confirmed.

He also led the first of several expeditions to San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán

San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán or San Lorenzo is the collective name for three related archaeological sites—San Lorenzo, Tenochtitlán and Potrero Nuevo—located in the southeast portion of the Mexican state of Veracruz. Along with La Venta and Tre ...

(1938), La Venta

La Venta is a pre-Columbian archaeological site of the Olmec civilization located in the present-day Mexican state of Tabasco. Some of the artifacts have been moved to the museum "Parque - Museo de La Venta", which is in nearby Villaherm ...

(1939–40) and Cerro de las Mesas (1940–41). In 1941, Stirling unearthed a large carved stone monument in Izapa

Izapa is a very large pre-Columbian archaeological site located in the Mexican state of Chiapas; it is best known for its occupation during the Late Formative period. The site is situated on the Izapa River, a tributary of the Suchiate River, ...

, which he labeled Stela 5.

Stirling was unable to return to La Venta until 1942, due to World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. When he did, he was to excavate several important artifacts. He then left for Tuxtla Gutiérrez

Tuxtla Gutiérrez, or Tuxtla, (, ) is the capital and the largest city of the Mexico, Mexican southeastern state of Chiapas. It is the seat of the municipality of the same name, which is the most developed and populous in the state. A busy govern ...

to attend a conference on the Maya and Olmec cultures, one that was to become a defining moment in modern ideas about the Olmec. It was here that Miguel Covarrubias and Dr. Alfonso Caso first presented the case for the Olmec culture as being the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, pre-dating even the Maya. Stirling supported their hypothesis, as he did Covarrubias in his interpretation of Olmec art. For example, Monument 1 at Río Chiquito and Monument 3 at Potrero Nuevo were, according to Stirling, the mythological union of a jaguar and a woman that produced "almost jaguar children".

It would be nearly 15 years before radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

finally confirmed that the Olmec pre-dated the Maya. The Olmec culture is generally considered to have lasted from 1400 BCE until 400 BCE.

Other work

Stirling began searching for links between Mesoamerican and South American cultures inPanama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, Ecuador, and Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

from 1948 to 1954. He was also the chief organizer of the seven-volume ''Handbook of South American Indians''.

He conducted excavations in the Linea Vieja lowlands of Costa Rica in the 1960s. Concentrating on tombs, he dug at five sites between Siquirres and Guapiles, and published a series of C- 14 dates ranging from 1440 to 1470 CE, and arranged much of the pottery excavated in an approximate chronological sequence.

In the Sierra de Ameca between Ahualulco de Mercado and Ameca, Jalisco, a large number of stone spheres, many of which are almost perfectly spherical, can be found. Their generally spherical shape led people to suspect they were manmade stone balls, called petrospheres, created by an unknown culture. In 1967, Stirling examined these stone spheres in the field. As a result of this examination, he and his colleagues hypothesized that they were of geological origin. A later expedition and subsequent petrographic and other laboratory analyses of samples of the stone balls confirmed this suspicion. Their interpretation of the data collected in both field and laboratory is that these stone balls were formed by high temperature nucleation of glassy material within an ashfall tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock co ...

, as a result of tertiary volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism, volcanicity, or volcanic activity is the phenomenon where solids, liquids, gases, and their mixtures erupt to the surface of a solid-surface astronomical body such as a planet or a moon. It is caused by the presence of a he ...

.Stirling, M.W., 1969, An Occurrence of Great Stone Spheres in Jalisco State, Mexico. National Geographic Research Reports. v. 7, pp. 283–286.

Other positions held

Stirling was president of the Anthropological Society of Washington in 1934–1935 and vice president of theAmerican Anthropological Association

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) is an American organization of scholars and practitioners in the field of anthropology. With 10,000 members, the association, based in Arlington, Virginia, includes archaeologists, cultural anthropo ...

in 1935–36. He received the National Geographic Society's Franklyn L. Burr Award for meritorious service in 1939, 1941 (shared with his wife Marion) and 1958. He was also on the Ethnographic Board, which was the Smithsonian's effort to make its scientific research available to the military agencies during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

After his retirement, Stirling was a Smithsonian research associate, a National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

collaborator, and member of the National Geographic Committee on Research and Exploration.

Stirling died in 1975, aged 78, after a period of illness associated with cancer.

Book collection

Marion Stirling donated around 5000 volumes from the Stirlings' library to the Boundary End Archaeology Research Center (earlier the Center for Maya Research). They include a collection of scholarly pamphlets and reprints from the mid-19th century on, complete runs of the American Anthropologist (1881– ); American Antiquity (1935– ), Bulletins 1–200 and Annual Reports 1–48 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, and all the Anthropological Papers of theAmerican Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

.

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology

The museum, in theUniversity of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, displays 165 Dyak and Papuan objects, including steel axes, basketry, arrows and wooden boxes, from Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

, donated by Stirling.

Films by Stirling

Preserved at the Human Studies Film Archive, Suitland,Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

:

* ''Exploring Hidden Mexico'' – Documents excavations at La Venta and Cerro de las Mesas.

* ''Hunting Prehistory on Panama’s Unknown North Coast'' – Documents the 1952 excavations of sites in Northern Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

.

* ''Aboriginal Darien : Past and Present'' – Documents the flora, fauna and ethnography of parts of Panama through a journey in 1954.

* ''On the Trail of Prehistoric America'' – Documents an Ecuador expedition in 1957, along with brief ethnographic footage of the Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

Indians.

* ''Mexico in Fiesta Masks''

* ''Uncovering an Ancient Mexican Temple''

* ''Exploring Panama’s Prehistoric Past''

* ''Uncovering Mexico’s Forgotten Treasures''

Bibliography

*''America's First Settlers, the Indians'' National Geographic, 1937 *''Great Stone Faces of the Mexican Jungle'' National Geographic, 1940 *''An Initial Series from Tres Zapotes'' Mexican Archaeology Series, National Geographic, 1942 *''Origin myth of Acoma and other records'' BAE Bulletin 135, 1942 *''Finding Jewels of Jade in a Mexican Swamp'' (with Marion Stirling) National Geographic, 1942 *''La Venta’s Green Stone Tigers'' National Geographic, 1943 *''Stone Monuments of Southern Mexico'' BAE Bulletin 138, 1943 *''Indians of the Southeastern United States'' National Geographic, 1946 *''On the Trail of La Venta Man'' National Geographic, 1947 *''Haunting Heart of the Everglades/Indians of the Far West'' (with A. H. Brown) National Geographic, 1948 *''Stone Monuments of the Río Chiquito'' BAE Bulletin 157, 1955 *''Indians of the Americas'' National Geographic Society, 1955 *''The use of the atlatl on Lake Patzcuaro, Michoacan'' BAE Bulletin 173, 1960 *''Electronics and Archaeology'' (with F. Rainey and M. W. Stirling Jr) Expedition Magazine, 1960 *''Monumental Sculpture of Southern Veracruz and Tabasco'' Handbook of Middle American Indians, 1965 *''Early History of the Olmec Problem'' Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, 1967 *''Solving the mystery of Mexico's Great Stone Spheres'' National Geographic, 1969 *''Historical and ethnographical material on the Jivaro Indians'' BAE Bulletin 117 *''An archeological reconnaissance in Southeastern Mexico'' BAE Bulletin 164 *''Tarquí, an early site in Manabí Province, Ecuador'' (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 186 *''Archaeological notes on Almirante Bay, Panama'' (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 191 *''Archaeology of Taboga, Urabá, and Taboguilla Islands, Panama'' (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 191 *''El Limón, an early tomb site in Coclé Province Panama'' (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 191Notes

External links

The Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec

* ttp://www.latinamericanstudies.org/stirling.htm The Latin American Studies' Stirling Page {{DEFAULTSORT:Stirling, Matthew Williams American ethnologists American Mesoamericanists Mesoamerican archaeologists Olmec scholars Smithsonian Institution people Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni American Episcopalians 1896 births 1975 deaths 20th-century Mesoamericanists 20th-century American archaeologists